7

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THUTMOSE III

It is no coincidence that the century of total war coincided with the century of central banking.

RON PAUL, AMERICAN PHYSICIAN, AUTHOR, AND FORMER MEMBER OF CONGRESS

AFTER THE LAST GREAT FLOOD, the Shemsu Hor slowly began to rebuild their culture. It’s likely that they survived for long periods underground and emerged sometime afterward to view the altered landscape. They would have noticed that the terrestrial civilization had a long way to go before reaching the high level of achievement their ancestors had enjoyed. Thousands of years passed, and life on Earth plodded along. During this time sub-Saharan Africa was dense with vegetation, and drawings of this tropical paradise adorned the cave walls at Tassili n’Ajjer, a mountain range in the Algerian regions of the Sahara Desert (see figure 7.1). Scenes on these walls depict strange animals and humans joined by unmistakable images of floating aliens wearing spacesuits and helmets.

It appears that either the Shemsu Hor in Africa were able to recreate some of their lost technology from the pieces that survived or they were visited by other Shemsu Hor from different areas of the globe. It is also possible that an interstellar version of the Shemsu Hor or other alien species visited our planet after the cataclysm and made contact with the indigenous Shemsu Hor. Maybe this cataclysm was of universal proportions and affected other planets. If so, this would certainly draw the attention of intelligent alien species that might be monitoring the galaxy in a sort of space federation as depicted on Star Trek or merely out of curiosity. Plausible theories are endless and may seem too far out, but it’s important to keep an open mind when analyzing an extremely ancient and crucial period in history.

Figure 7.1. Ancient horn-headed alien giant petroglyph (from 10,000 BCE), found in Tassili National Park, Algeria.

The means by which the Shemsu Hor achieved their goal of regaining lost technology on Earth remains a mystery, but somehow they did so. Early in Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty (1539–1295) they made their mark on human civilization. The human society that was developing in Egypt was beginning to emerge as a civilizing force. Similar cultures evolving near the Nile, in the greater Middle East, and in Asia were also developing at a rapid pace. The Egyptian empire prospered, and the pharaohs’ obsession with the ancient gods was at an all-time high. Their ponderings about these mysterious forebears of civilization must have been similar to ours, since they weren’t around during the original Golden Ages, either. And like us, all they had to guide them were bizarre myths and legends.

The Shemsu Hor infiltrated the Amun priesthood and, over time, slowly turned it into the Brotherhood of the Snake. The pharaoh who ruled Egypt during this time was Akhenaten’s great-great-great grandfather, Thutmose III (1504–1426). This pharaoh possessed all the qualities of a great ruler, and more important to the Shemsu Hor, he seemed to be military minded—a big advantage if they planned on turning human society into patriarchal rule. This movement was stalled temporarily, largely due to the matriarchal reign of Queen Hatshepsut, a female monarch. Hatshepsut’s era (1479–1458) was notable for its lack of wars, as she restored the original divine principles to Egyptian society. Her philosophy promoted worship of the creative mother principle; she also taught her subjects how to live in harmony with both the sacred feminine and the masculine dualities of human beings.1 This ancient way of living and worship served no purpose to the Shemsu Hor. If we take a look around our current society, it still doesn’t serve the purposes of the power elite.

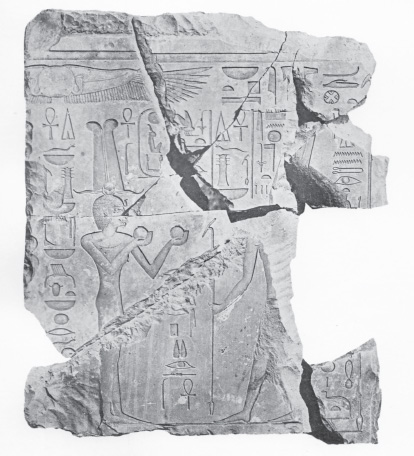

Queen Hatshepsut was an obstacle to the Shemsu Hor, and she mysteriously “disappeared” during an outing one evening with Thutmose III, who eventually tried to chisel her out of history (see figure 7.2).

With the uncooperative Queen Hatshepsut out of the way, Thutmose III seized full power in Egypt. Thutmose came of age at the perfect time for the Shemsu Hor to orchestrate a spectacular aerial showing that would subjugate him and future pharaohs to the reptilian overlords. This defining moment in history (1482)—found in the annals of the Nile civilization—had a profound impact on Thutmose III and undoubtedly spooked the Egyptian people who witnessed the UFO encounter. This encounter is not only depicted in the walls of Karnak but also documented. The well-known Tulli Papyrus describes this event, which was recorded by the pharaoh’s scribes during the eighteenth dynasty. This controversial document, originally part of the Royal Annals of Thutmose III, has sparked countless debates within academic circles concerning its authenticity.

Figure 7.2. Chiseled limestone bust of Hatshepsut. Courtesy of Henri Chevrier.

The original papyrus was written in hieratic, which is a simple style of cursive writing that was used for everyday purposes. The Italian-Russian Egyptologist, Prince Boris de Rachewiltz, an accomplished scholar and the heir of Ezra Pound’s “vast library of rare medieval magick manuals,”2 laboriously studied and translated the papyrus that he acquired, among other assorted documents and papers belonging to Professor Alberto Tulli.

Rachewiltz, in the 1930s one of the world’s most sought-after Egyptologists, was the man responsible for saving this slice of forgotten history. He complained about the disastrous state of the papyrus, noting that both the beginning and ending were missing, along with several pieces of untranslatable text. With no expectations out of the ordinary, Rachewiltz stumbled into translating the eighteenth-dynasty UFO encounter. As soon as the translation was published, it was embroiled in controversy.

Professor Tulli was the director of the Vatican’s Egyptian Museum, and it’s likely he obtained the papyrus on the black market, since the Vatican has no official listing of its purchase. However, the Vatican has acknowledged its existence in response to an official inquiry, headed by Dr. Edward U. Condon, in a U.S. government–supported investigation into UFOs in 1966. Apparently, officials at the Pentagon were so curious about the Tulli Papyrus that they sent an inquiry to Dr. Walter Ramberg, the head scientist at the U.S. Embassy in Rome, asking for proof of its existence.

Ramberg replied with discouraging news:

The current director of the Egyptian Section of the Vatican Museum, Dr. Nolli, said that Prof. Tulli had left all his belongings to a brother of his who was a priest in the Lateran Palace. Presumably the famous papyrus went to this priest. Unfortunately the priest died also in the meantime and his belongings were dispersed among heirs, who may have disposed of the papyrus as something of little value.3

Legend has it that Professor Tulli acquired the papyrus at a Cairo bazaar in 1934 from Phocion J. Tano, a respected antiquities dealer, and then asked Dr. Etienne Drioton at the Cairo Museum to translate the cursive hieratic text into simple hieroglyphics, a common practice that makes the document easier to read. Dr. Drioton would later be named director general of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities and would write several books on ancient Egypt that are still highly influential and referenced as authoritative works by esteemed scholars and authors. When Professor Tulli died in 1952, these translated documents came into the possession of his brother, Gustavo, who then handed them over to the distinguished Egyptologist Rachewiltz.

Phocion J. Tano, the man who originally sold Tulli the manuscripts, was the former proprietor of the Cairo Antiquities Gallery, and a renowned collector and student of history. Tano’s many years of experience and his good standing within Cairo’s academic circles would have been shattered if he had come within shouting distance of fake or hoax manuscripts. As a matter of fact, given the highly distinguished careers of everyone involved with the history of the Tulli Papyrus—Tulli, Tano, Drioton, Rachewiltz—it is doubtful any one of these men would have risked his reputation for a hoax that would not benefit any of them.

The main proponent of the hoax theory is an Italian professor, Franco Brussino, of no notable background, who claims that Tulli copied select pieces from Alan Gardiner’s Egyptian Grammar, a book published in 1927. Brussino misses the point: many Tulli-like phrases are common and can be found by looking at the Budge translations from the Book of the Dead, which is more than likely where Gardiner got his source material. This has only added another layer to the cover-up,4 considering that Brussino’s case falls apart instantly when we question why anyone would fake a papyrus detailing close encounters of the third kind decades before the subject of UFOs was even considered.

The great lengths to which skeptics have gone to undermine the authenticity of the Tulli Papyrus are absurd and rather suspicious. Rachewiltz, the man responsible for translating the papyrus, was one of the foremost experts in Egyptology in his time. He authored several scholarly works that are still used in university curriculums today.

At the core of the mystery of the papyrus are the references it makes to Circles of Fire. This also happens to be the traditional glyph translation for island and is similar to the Hebrew translations of the nimbus or thundercloud, as discussed in previous chapters. These Circles of Fire, or islands, not only resemble solid formations—unlike circles, which have gaping holes—but also are located in the sky, high above the Egyptians, so these islands clearly have nothing to do with land-based, geographical formations.5

What the scribes witnessed were fiery disks blazing across the sky, high above the Egyptian people, who watched in stunned amazement. Thutmose III ordered that a description of this event be recorded for posterity. The encounter didn’t end there. The number of disks began to increase as the days passed, eventually culminating in a large fleet of UFOs that hovered above the pharaoh’s empire. Before this fleet disappeared into the southern horizon on a winter night more than 3,500 years ago, the commanders made contact with Pharaoh Thutmose III. When he met the gods of this space fleet at a private location in the desert, he was introduced to the Shemsu Hor and given the opportunity of a lifetime. But before they could be certain that Pharaoh Thutmose III was indeed the leader they had in mind, they had to make sure by initiating him into the mysterious ways of heaven.

This meant that Thutmose was given a ride by the Shemsu Hor into Earth’s upper atmosphere, like other prophets before him; namely, Elijah and Enoch. Below is Rachewiltz’s original translation of this bizarre event, first published in 1953:

In the year 22 third month of winter, sixth hour of the day . . . the scribes of the House of Life found it was a circle of fire that was coming in the sky [though] it had no head, the breadth of its mouth [had] a foul odour. Its body 1 rod long [about 150 feet] and 1 rod large. It had no voice . . . Their hearts become confused through it, then they laid themselves on the bellies . . . They went to the King . . . ? to report it. His Majesty ordered . . . has been examined . . . as to all which is written in the papyrus-rolls of the House of Life His Majesty was meditating upon what happened. Now, after some days had passed over these things, Lo! They were more numerous than anything. They were shining in the sky more than the sun to the limits of the four supports of heaven. . . . Powerful was the position of the fire circles.6

The prominent anthropologist R. Cedric Leonard also translated the papyrus with similar results, yielding a more fluid translation:

In the year 22, of the third month of winter, sixth hour of the day . . . among the scribes of the House of Life it was found that a strange Fiery Disk was coming in the sky. It had no head. The breath of its mouth emitted a foul odor. Its body was one rod in length and one rod in width. It had no voice. It came toward His Majesty’s house. Their heart became confused through it, and they fell upon their bellies. They [went] to the king, to report it. His Majesty [ordered that] the scrolls [located] in the House of Life be consulted. His Majesty meditated on all these events which were now going on. After several days had passed, they became more numerous in the sky than ever. They shined in the sky more than the brightness of the sun, and extended to the limits of the four supports of heaven . . . Powerful was the position of the Fiery Disks.7

Part of this encounter, found in the annals of Thutmose III, was written on the walls of Karnak and offers a firsthand narrative. Although the wall hieroglyphs are missing the portions relating to the fiery disks, the temple walls of Karnak do illustrate the pharaoh’s meeting with the Shemsu Hor and the flight afterward. In the writings the pharaoh associates the Shemsu Hor with the sun god Ra because of the great technological magic they had performed for him.

In Divine Encounters Zecharia Sitchin describes the fateful meeting after “Amon-ra appeared in his glory from the horizon.” Thutmose III arrived as the hand-picked future monarch of Egypt, chosen with some help from the Shemsu Hor’s “working of miracles.” Sitchin writes about the pharaoh’s space odyssey, which made him “full with the understanding of the gods.” This is mentioned briefly between numerous accounts of wars and plundering on the walls of Karnak:

He opened for me the doors of Heaven; He spread open for me its portals of horizon.

I flew up to the sky as a divine Falcon, able to see his mysterious form, which is in Heaven, that I might adore his majesty. [And] I saw the being-form of the Horizon God in his mysterious Ways of Heaven.8

Brad Steiger, the world-renowned author of the influential Worlds before Our Own and more than 170 other books, is probably the planet’s most popular and beloved scribe of unexplained phenomena. Steiger says, “This encounter, which took place over 3,400 years ago, shows that aliens did not just recently start exploring our planet” and that “the report of Thutmose III proves that ancient astronauts visited Earth long ago.”9

Another interesting aspect of the Tulli Papyrus is the similarities in prose style it shares with the book of Ezekiel, supposedly written nine hundred years later. Drawing on these similarities, we might posit that the Tulli Papyrus might have served as an inspiration to the Hebrew scribes who rewrote sections from the Annals of Thutmose III, replacing Egyptian characters with Jewish ones. Some examples of these prose similarities include:

Egyptian = Ezekiel

the House of Scribes = the House of Israel

was coming in the sky = the heavens were opened

it was a circle of fire = wheel of fire

it had no head = heads with four faces [everything had “four faces”]

It had no voice = I heard a voice that spake

toward the south = out of the north

the brightness of the sun = and a brightness was about it

His Majesty ordered . . . written in rolls = God spread a roll before me and it was written . . .

in the land of Egypt = I am against pharaoh, king of Egypt

Fishes . . . fell down from the sky = thee and all the fishes: thou shalt fall upon the open fields10

The main problem, of course, is that the Tulli Papyrus is nowhere to be found. Most likely, it is in private hands. This is the ultimate issue concerning this astounding document, which has been sought after by both scholars and officials at the highest levels of government.

After taking his flight and receiving the stamp of approval from the Shemsu Hor, Thutmose III catapulted to instant fame as a warmongering pharaoh. An accomplished charioteer, archer, athlete, and soldier, he organized huge armies that marched thousands of miles, obliterated his foes, and captured new lands and kingdoms. He has been compared to Napoleon and Alexander the Great as one of the few people in history to expand the borders of their empire to encompass the entire known world. Most certainly, he was aided in accomplishing this feat by the technology of the Shemsu Hor. Unlike Napoleon and Alexander the Great, Thutmose III never lost a battle nor was he poisoned to death while still in his prime (see plate 20). Through the course of sixteen military campaigns, Thutmose III conquered Palestine, Syria, and Nubia, and his impact on Egyptian culture was profound.

Thutmose III was seen as more than a pharaoh; he was celebrated in Egypt as a national hero. Egyptologists today regard him as the greatest pharaoh who ever lived. He created the largest empire seen in Egypt and attempted to erase all trace of the memory of Hatshepsut’s brief return to matriarchal rule. He did all this while the Shemsu Hor quietly pulled the strings behind the curtains, like the wizards they were. While Thutmose III propelled his empire into a superpower, through wars and conquest, an advanced civilization sprang up in Egypt.

Thutmose III constructed over fifty new temples and built magnificent tombs and obelisks, showcasing the sophisticated craftsmanship that suddenly evolved during his reign. During this era groundbreaking advances were made in art and design, including astounding works of relief architecture, sculpture, painting, and glass making, all of which stand apart from the works of previous pharaohs (see plate 21). This swift leap forward points to the Shemsu Hor and the Golden Age knowledge they alone had. This knowledge gave them full control of the destiny of Egypt—or so they thought.

Through the spoils of war and the reign of their puppet ruler, Thutmose III, the Shemsu Hor created a wealthy society that began to use gold and silver instead of the usual barter system of disposable goods and agricultural resources.11 These victories allowed the Brotherhood of the Snake to establish a central banking system, carefully disguised beneath the rule of the Amun priesthood. The founding of this central bank—fronted by the priesthood and run behind the scenes by the Brotherhood of the Snake, a.k.a. the Shemsu Hor—was the watershed moment in the reign of Thutmose III. This central bank helped work out the kinks in the banking system and established the blueprint for how society was to be run in the postdiluvian world.

The Shemsu Hor began setting up their new empire by taking over the Amun priesthood and installing pharaohs who served as puppet rulers. This bit of theater got the people to believe that power rested in the hands of the pharaoh, not the priests. They never knew that the real rulers were behind the scenes. This is a time-tested practice that keeps citizens under tight control by letting them believe they, or their leaders, hold the reins, when another entity is actually pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Over time, the celebrated Thutmose III died and was replaced by another puppet pharaoh who continued the practice of expanding borders, central banking, and patriarchal rule. The Shemsu Hor operated behind the pharaoh’s throne while the Amun priesthood blossomed into the dominant power of ancient Egypt.

A hundred years went by, and society flourished, as the various pharaohs who succeeded Thutmose III played out their roles according to the Shemsu Hor script. The Brotherhood of the Snake’s plan of total domination was going smoothly until a pesky child prodigy came along. Developing conscientious opinions and ideas that didn’t accord with the Brotherhood of the Snake’s plans, this particular pharaoh grew up to be a royal pain to the establishment and sparked a civil war so intense that what we call our modern world was born from its ashes.