8

AKHENATEN VERSUS THE BROTHERHOOD OF THE SNAKE

There’s a plot in this country to enslave every man, woman, and child. Before I leave this high and noble office, I intend to expose this plot.

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY, SEVEN DAYS BEFORE HE WAS MURDERED ON NATIONAL TELEVISION

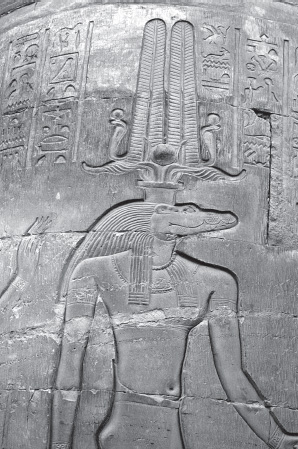

BEFORE AKHENATEN BEGAN HIS QUEST to develop what is known as the first monotheistic culture in recorded history, the Brotherhood of the Snake was the unchallenged authority of Egypt. They governed the people through politics and religion, respectively; that is, through puppet pharaohs and the Amun priesthood. They molded, shaped, and reshaped the world at their whim and experimented with the antediluvian knowledge that was now their legacy. The crocodile-headed god Sobek secretly represented the Brotherhood of the Snake and was worshipped alongside Ra as a deity of creation.

Sobek, a god associated with Egyptian creation myths, was said to have been the first to emerge from the water of chaos, and he is thought to have helped build and destroy previous civilizations.1 Sobek was initially associated with fertility, but during the reign of the Brotherhood of the Snake, he became known as a mighty military deity and his name was added as a suffix on receipts related to precious metals, minerals, and money (see figure 8.2). Even the origin of the word messiah stems from Sobek and his reptilian relatives, sometimes referred to as either messeh or mus-hus. As noted in The Dragon Legacy:

Figure 8.1. Aamerut praying to the reptilian god Sobek. Courtesy of Rama.

It was from the practice of kingly anointing with the fat of the messeh that the Hebrew verb mashiach [to anoint] derived, and the Dragon dynasty became known as Messiahs [anointed ones].2

Figure 8.2. Sobek. Courtesy of Hedwig Storch.

The Brotherhood of the Snake made sure their ancient genealogies survived the progression of millennia by having symbols of their existence embedded in our awareness. Their mark can still be found on the caduceus rod that’s encircled by two snakes on the seal of the American Medical Association. It is no coincidence that the pharmaceutical industry, comprising the biggest and most powerful corporate conglomerates in the world, cleverly assigns the Rx tag to every bag or bottle of medicine we buy. Though it’s supposed to mean “treatment” and is used as a doctor’s shorthand scribble, Rx represents the eye of Horus and is pronounced “Rex,” which is the ancient meaning of the word king or monarch.3 This is another clue to who really rules the world.

The Brotherhood of the Snake ran Egypt during the eighteenth dynasty, a time of exceptional cultural advancements. Imagine their shock when one of their own turned on them and threatened to expose their fraudulent system. This individual has become the most misunderstood and controversial figure in all of history, with a life so mired in disinformation and complicated truths that he remains the world’s hardest puzzle to solve. Of all the characters in the past, one man stands out like a sore thumb. At times he has been called Akhnaton, Ikhnaton, Amenophis, or Amenhotep IV, but to most he is simply known as Akhenaten.

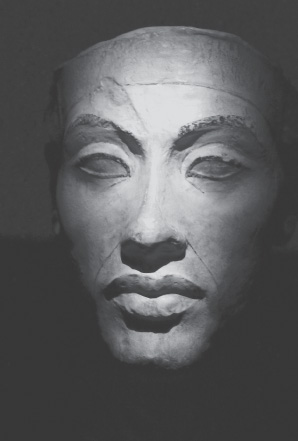

Figure 8.3. Casting of Akhenaten’s head found in the workshop of the sculptor Djehutimes at Amarna. The original is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The photo was taken at VAM Design Center, Budapest, at the Treasures exhibition. Courtesy of HoremWeb.

He’s more popular than ever, thanks to the conspiracy theories of “Freeman,” a researcher who correctly predicted the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Freeman claims that President Barack Obama was cloned in a laboratory from the DNA of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Freeman’s fantastically wild DVD, Obama Cloning and the Coming Space War, is informative, funny, and utterly original.4 One can’t type Akhenaten’s name into a search engine anymore without inevitably crossing paths with Obama and links that lead to YouTube footage showing them merging together, forming the grandest of conspiracies. This so-called conspiracy becomes even more bizarre when we examine the ancient representations of Akhenaten’s family and the striking similarities they share with Obama’s clan. Placing reproductions side by side, Michelle Obama looks exactly like Akhenaten’s mother, Queen Tiye, and the Obamas’ two daughters, Malia and Sasha, resemble Akhenaten’s daughters by Nefertiti. This odd bit of pop culture only makes Akhenaten’s legacy even more confounding.

Born as the youngest son of Amenhotep III and his chief queen, Tiye, and named Amenhotep IV, this young man grew up in the royal palace with no expectations of being a future ruler, since that job had already been promised to his older brother, Crown Prince Thutmoses, a high priest of Memphis.5 The historical records of Amenhotep IV’s youth are so sketchy that we know almost nothing about his early days. However, he appears to have been the black sheep of the family.

It’s possible that the future pharaoh inherited genetic memories of matriarchal philosophies taught before the age of the warrior pharaoh who dominated Egypt at the time of his birth. He had four sisters and was close to his mother. Perhaps they played a key role in shaping his views, which must have been looked down upon by his combatant pharaoh father and his Shemsu Hor–worshipping older brother. Amenhotep IV was never shown in any family portraits, and there is no record of his attending any public events with his father, Pharaoh Amenhotep III, a man known as “the magnificent,” whose forty-year reign was characterized by unbridled prosperity and artistic grandiosity, as well as by wars as he was influenced by the Shemsu Hor.

Figure 8.4. Relief of King Amenhotep III in limestone. Theben West, New Kingdom, eighteenth dynasty, ca. 1360 BCE. His features aren’t elongated, as Akhenaten’s were, and there are snakes interwoven in his headdress. Egyptian Museum, Berlin. Courtesy of Andreas Praefcke.

Amenhotep III was responsible for the groundbreaking temple building during Egypt’s peak as an artistic and international powerhouse. He was the Shemsu Hor’s favorite pharaoh, and they must have shared with him the secrets of Golden Age megalithic building. We can draw this conclusion because Amenhotep III is credited with constructing the massive pylon and colonnade extensions found at the temples of Karnak and Luxor, the Colossi of Memnon statues, and, most likely, the unfinished obelisk at Aswan (see figures 8.5 and 8.6).6

These granite blocks, some weighing over four hundred tons apiece, would be impossible to duplicate today. This means that either these works were constructed before the floods or that Egyptian high priests, under the guidance of the Shemsu Hor, shared these advanced building secrets with Amenhotep III. No matter what the truth is, there they stand in defiance of our theories. When Amenhotep III died of what most experts believe were natural causes, Egypt was at the peak of its power and dominated the international landscape as the most respected and feared country in the known world.

Figure 8.5. Colossi of Memnon, guarding the passage to the Theban necropolis. West Bank section of Luxor, Egypt. Courtesy of Przemyslaw Idzkiewicz.

Figure 8.6. This unfinished obelisk is the largest known ancient obelisk located in Aswan. Courtesy of Olaf Tausch.

No one knows how Amenhotep IV felt about his father’s death, nor is it known how his brother, Thutmoses, died unexpectedly shortly thereafter. These sudden departures wound up leaving the throne in the hands of the impressionable Amenhotep IV, a young man who seemingly didn’t want anything to do with the responsibility of being pharaoh. The deaths of Amenhotep III and his eldest son, Thutmoses, meant nothing to the Brotherhood of the Snake, since they maintained control of the political and religious power centers through the Amun priesthood. They saw the mental and charismatic potential that the young pharaoh possessed and figured the people of Egypt would easily accept the new ruler.

Amenhotep III’s younger son had no choice but to step into his father’s shoes, even if these were big ones, and he became the tenth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty. Things were going fine for the Brotherhood; the first few years of Amenhotep IV’s reign passed without incident. He was a favorite of the Egyptian people, and the young pharaoh’s charisma, the likes of which had never been seen before, made him the world’s first teenage celebrity. But despite the easy living and fanfare, something happened to the young boy-king that made him change his mind about everything.

It’s assumed that his relationship with Nefertiti blossomed during this time and that he began to carefully examine what was going on behind the scenes of the Amun priesthood. Had he figured out the great game? Did Nefertiti and members of her mysterious bloodline persuade the pharaoh that he was the real ruler and not the priesthood? Did he have genetic memories of past Golden Ages, and did he realize that the Amun priests weren’t using the sacred knowledge for the proper reasons? These questions have haunted historians for over 150 years and, unless we can develop a time machine, it’s likely we’ll never know the true answer to these questions.

What we do know is that during Amenhotep IV’s early reign as pharaoh, Egypt was the richest nation on Earth, and most of this wealth was controlled by the Amun priesthood. The priesthood represented a form of organized religion, using the Egyptian deities as tools to sow fear and enslave the population.7 The more deities to worship the better, meaning there would be more things to buy and, of course, more things to create. Since religion was the “big business” of the time, it’s likely that over 75 percent of the Egyptian population earned their living in connection with the worship of gods.

The practice of buying different statues and spells for the purpose of protection or the guarantee of a nice spot in the afterlife was a popular and much encouraged tactic that kept the riches flowing into the hands of the Amun priesthood. The ancient religious practice of instilling fear into a population worried about their souls, in order to acquire money from them, is a profitable one that has been repeated throughout history. This tradition may go unimpeded for ages, but no matter how well organized the plan is, the unknown element may throw a wrench in the works. For instance, the German Martin Luther rebelled against the Catholic Church in the 1500s for selling salvation certificates by defiantly nailing his challenge to this practice on the church’s front door.8 This bold act shook up the religious power structure and caused a wave of paradigm shattering and bloodshed. The young Amenhotep IV did something similar in ancient Egypt.

Making the brash move to take the power out of the hands of the Amun priesthood, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “Amun is satisfied” or “Effective spirit of Aten,” and began to close down the temples run by the Brotherhood of the Snake. Intent on restoring the religion of predynastic Egypt, in which the people worship only the Sun, Akhenaten disregarded the other deities; these were important to the Amun priesthood only as revenue streams. This radical shift in thinking shocked the Brotherhood of the Snake and threatened to put them out of business for good. Knowing the danger his actions posed to his life, Akhenaten began taking steps to get as far away as possible from the Amun priesthood. He decided to establish an entirely new metropolis for himself called Horizon of the Aten, now known as Amarna, a city constructed halfway between Memphis and Thebes.

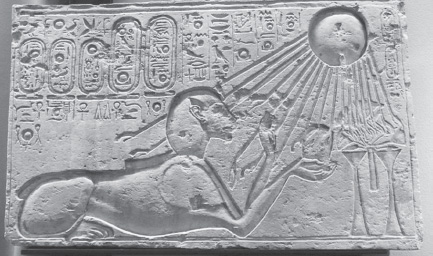

Figure 8.7. This stone block, which portrays Akhenaten as a sphinx, was originally found in the city of Amarna. This object is now located in the Kestner Museum in Hanover, Germany. Courtesy of Hans Ollermann.

The celebrated biographer Arthur Weigall wrote the first and most influential biography of Akhenaten in 1910 and imagined how the young pharaoh must have seen the lands belonging to the future site of Amarna:

Down the river it would seem that the young pharaoh now sailed in his royal dahabiyeh, looking to right and left as he went, now inspecting this site and now examining that. At last he came upon a place that suited his fancy to perfection. It was situated about 160 miles above the modern Cairo. At this point the limestone cliffs upon the east bank leave the river and recede for about three miles, returning to the water some five or six miles farther along. Thus a bay is formed which is protected on its west side by the river in which there lies a small island, and in all other directions by the crescent of the cliffs. Upon the island he would erect pavilions and pleasure-houses. Along the edge of the river there was a narrow strip of cultivated land whereon he would plant his palace gardens, and those of the nobles’ villas. Behind this verdant band the smooth desert stretched, and here he would build the palace itself and the great temples. Behind this again, the sand and gravel surface of the wilderness gently sloped up to the foot of the cliffs, and here there would be roads and causeways whereon the chariots might be whirled in the early mornings. In the face of the cliffs he would cut his tomb and those of his followers; and at intervals around the crescent of these hills he would cause great boundary stones to be made, so that all men might know and respect the limits of his city. What splendid quays would edge the river, what palaces reflect their whiteness in its waters! There would be broad shaded avenues, and shimmering lakes surrounded by the fairest trees of Asia. Temples would raise their lofty pylons to the blue skies, and broad courts should lie stretched in the sunlight. In Akhnaton’s youthful mind there already stood the temples and the mansions; already he heard the sound of sweet music.9

During the fifth year of his reign, Akhenaten began building Amarna in hopes of establishing a treasury for the Egyptian state based on the country’s private reserves of gold. This would take the source of the financial power away from the Amun priesthood, essentially put ting an end to their central banking scheme.

Let the chronicles of history show that Pharaoh Akhenaten was the first revolutionary to challenge the powers of the banking establishment. Akhenaten dismantled the Old World Order that had been in place for over a thousand years and confiscated the wealth of the Amun priesthood, closing their temples and leaving most abandoned and in ruins. During his reign, he also began to wipe out the gods associated with the Amun priesthood and obliterated hundreds of images of deities found on temple walls, obelisks, and tombs.

Figure 8.8. Small Temple of Aten at Tell el-Amarna. Courtesy of Einsamer Schütze.

While at Amarna, Akhenaten established a cult based on Aten, the sun god Ra, and made the official logo a rayed disk with outstretched hands of sunbeams. The arts at Amarna flourished, and for a few years Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and the royal family enjoyed a private renaissance of art and thought in their personal Camelot beneath the scorching Sun. Akhenaten attempted to usher in a new Golden Age, based on the knowledge he gained from the Shemsu Hor, genetic memories, or from his personal gut feeling that what was going on was not the way things were supposed to be.

What sets him apart from most people in history is that when he encountered evil, he didn’t choose to make a backroom deal to benefit himself, but rather confronted it head-on. Plus, he was pharaoh. He already had it all—and discarded the material for ideals and principles. It’s likely that Akhenaten was truly the last man who understood the Golden Age secrets of the universe—secrets like free energy, antigravity, stargates, wormholes, and quantum mathematic theories that we’re still searching to understand.

But while Akhenaten attempted to impart and communicate these ancient secrets, the streets of Egypt were tossed into anarchy and disarray. According to author and theologian Ralph Ellis:

Egypt had been a relatively stable society for thousands of years, both before and after this rebel pharaoh, the capital cities, temples, gods, arts, and social grades of the empire had changed little. Akhenaton would change them all. His whole career was out of the ordinary.10

While Akhenaten and Nefertiti were being depicted on ground-breaking art within the confines of Amarna, the outside world was in tumult. By upsetting the long-established balance of power between the priesthood and the pharaoh, Akhenaten plunged the country into massive unemployment and was no longer viewed as a charismatic leader, but rather as a sadistic dictator. His life was now in danger not only from the Brotherhood of the Snake but also from Egypt’s general population. As the years passed, armed military guards heavily surrounded Akhenaten’s Amarna, a city transformed into an isolated compound.

As his reign entered its twelfth year, the people were extremely disillusioned with their pharaoh, now viewing him as an evil villain or a “heretic king,”11 resulting in large expressions of public unrest.

Akhenaten might have been an amazing artist, poet, and philosopher, but he wasn’t a ruler. Toward the end of his reign, for the first time in Egyptian history, his cabinet was not composed of priests, but entirely of army generals:

It is apparent that during the Eighteenth Dynasty the personnel surrounding the king included a significant number of high-ranking army officers . . . A central feature of Akhenaton’s government is that his immediate entourage was drawn directly from the military . . . If we take the reliefs at face value, then it could be argued that the city of Akhenaton was virtually an armed camp! Large platoons march at double speed, or stand at ease, and it is noticeable that these forces are never very far away from the figure of Akhenaton. There are soldiers under arms standing in front of the palaces and the temples, and in the watchtowers which border the city.12

Figure 8.9. Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children. Courtesy of Gerbil.

While Akhenaten continued his reign under heavy military protection, the rest of Egypt wasted away, due to the upheaval caused by ousting the Amun priesthood:

The temples of the gods and goddesses, beginning from Elephantine down to the marshes of the Delta, had fallen into neglect. Their shrines had fallen into desolation and become terraces overgrown with weeds. Their sanctuaries were as if they had never been. Their halls were a trodden path. The land was in confusion.13

And from the Stele of Tutankhamen, discovered in Karnak in 1905 and translated in 1923 by E. A. Wallis Budge:

The whole country was in a state of chaos, similar to that in which it had been in primeval times [i.e., at the Creation]. From Abu [Elephantine] to the Swamps [of the Delta] the properties of the temples of the gods and goddesses had been destroyed, their shrines were in a state of ruin and their estates had become a desert. Weeds grew in the courts of the temples. The sanctuaries were overthrown and the sacred sites had become thoroughfares for the people. The land had perished, the gods were sick unto death, and the country was set behind their backs.14

Akhenaten sent the military out to gather resources and make sure the Amun priesthood had been run into the ground. Unfortunately, these unmatriarchal tactics were necessary if Akhenaten’s determination to end the Amun priesthood were to be taken seriously. However, when fighting fire with fire, those participating in the fight eventually get burned. Military corruption intensified, and commando raids of terror swept across Egypt in Akhenaten’s name:

The temple walls were mutilated by the Atenites, the priesthoods were driven out, and all temple properties were confiscated and applied to the propagation of the cult of Aten. The figures of the great gods that were made of gold and other precious metals in the shrines were melted down, and thus the people could not consult their gods in their need, for the gods had no figures wherein to dwell, even if they wished to come upon the Earth. There were no priests left in the land, no gods to entreat, no funeral ceremonies could be performed, and the dead had to be laid in their tombs without the blessing of the priests.15

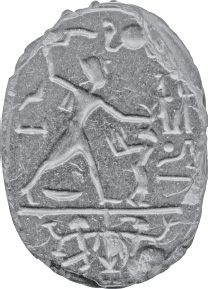

Figure 8.10. Scarab showing a pharaoh executing the enemy. Courtesy of Henry Walters.

By eliminating the power of the Amun priesthood, levying taxes upon the people, and emptying the coffers of Egypt to pay for the construction of his dream city and other Theban temples, Akhenaten bankrupted and ruined Egypt. But he did accomplish his goal of crushing the Brotherhood of the Snake and the Amun priesthood. Akhenaten effectively destroyed an integrated system of politics, economics, family banking dynasties, and religion that had been entrenched in Egypt for at least seventeen hundred years.

His actions are comparable to Jesus’s, when he stormed the temples of Jerusalem and kicked out the moneychangers or bankers, but on a grander scale, since Akhenaten was a ruler. Another similarity the Bible shares with Akhenaten is Psalm 104, which is an almost exact copy of a hymn to Ra that Akhenaten wrote when he was twenty-one years old. Preserved from the Papyrus of Hu-nefer, Akhenaten’s hymn left biblical archaeologists who recognized the similarities with Psalm 104 astounded, since it is in conflict with the belief that the Bible was written as the true and only word of God. Psalm 104 stands out as the only passage in the Bible that ascribes to the Lord characteristics of the Sun.16 The fact that Akhenaten’s poetry can still be found in one of the world’s most popular books is a testament to his principled and swift mind and how far ahead of the times he truly was.

Unfortunately, being misunderstood is the fate of all true genius and not only was Akhenaten misunderstood, he also had a sizable bounty placed on his head. It was only a matter of time before the hangman came to collect. More than fifteen years after Akhenaten began his revolution, he found himself isolated and alone to face the uncertain end of his reign in Amarna. Nefertiti’s disappearance17 during the final years of his reign suggests that Akhenaten sent her away to foreign lands in order to save his family. It’s likely that the beautiful Nefertiti served as the inspiration of the future myths of Mary Magdalene and the bloodlines of the Holy Grail (see plate 22).

It’s also probable that Akhenaten’s story eventually morphed into the Hebrew tale of Moses. However, it is wrong to assume that Akhenaten was Moses, as some thinkers, like Sigmund Freud, propose.18 Why? Because instead of fleeing to the desert in an exodus, Akhenaten stayed in Amarna. He had built the city and empire in an ultimate act of rebellion, and despite feeling the noose tightening around his neck, he remained there to the end.

All his youthful dreams and arrogance came full circle to crush his naïve heart:

It was an era which, though starting off well enough, had degenerated rapidly into mayhem and widespread religious persecution, an orgy of wanton destruction and almost total economic collapse. For the events he set in train, Akhenaten could never be forgiven: with a ruthlessness not seen in Egypt before or since, Amarna, both as a city and a concept, was razed and all trace of Pharaoh’s existence systematically expunged.19

Akhenaten’s vision of a future Egypt free from the clutches of the Brotherhood of the Snake was an illusion. His kingdom crumbled, and Hittite warriors took advantage of the chaos, swooping down on Egypt, violently sacking towns, and conquering the pharaoh’s outposts in Syria and Palestine. As his empire was decimated by foreign invaders Akhenaten did nothing to stop the assault. Heartbreaking pleas from generals, asking for help, can be read in the Amarna Letters, transcribed from a series of clay tablets that are some of the most important surviving relics from the Amarna era. Akhenaten ignored the cries for help, already knowing that his reign was over and there was nothing left worth fighting for.

His revolution failed:

The tribute having ceased, the Egyptian treasury soon stood empty, for the government of the country was too confused to permit of the proper gathering of the taxes, and the working of the gold-mines could not be organized. Much had been expended on the building of the City of Horizon, and now the King knew not where to turn for money. In the space of a few years Egypt had been reduced from a world power to the position of a petty state, from the richest country known to man to the humiliating condition of a bankrupt kingdom. Surely one may picture Akhnaton now in his last hours, his jaw fallen, his sunken eyes widely staring, as the full realisation of the utter failure of all his hopes came to him.20

Knowing that his final hour might be near, Akhenaten commissioned statues and busts of him, showing large, bizarrely slanted eyes and elongated facial characteristics. Some of these representations of Akhenaten feature clear serpentine traits that are unique in the artistic representation of the pharaohs. Images found in the Amarna art records depict the members of his royal family with distended and elongated skulls. Most scholars assume that they must all have been suffering the symptoms of Marfan syndrome, a rare genetic disorder of the connective tissues that strengthen the body’s bone structure. But considering that Akhenaten’s bloodline stemmed from either the Hyksos or another unknown foreign ruling influence, and was not entirely Egyptian, there’s a good chance that they might have inherited these elongated features from their ancient alien relatives.

Figure 8.11. Akhenaten. This rare bust was discovered in Karnak and is now at the Cairo museum. Courtesy of José-Manuel Benito.

It is also possible that Akhenaten was a descendent of the Shemsu Hor. After all, the circuitous manner in which he rose to the throne of Egypt leaves open a door to speculation, as does the bold way in which he felt justified in demolishing the Brotherhood of the Snake cult. He may have descended from another form of humanoid species that survived in small numbers after the floods.

Figure 8.12. Another likeness of Akhenaten. Courtesy of Paul Mannix.

No matter where his roots lay, Akhenaten was a man out of time, born to communicate a story of good versus evil thousands of years after his revolution near the Nile. Despite his strange, alien-esque features, found throughout the artistic remains in Amarna, it’s more than likely that Akhenaten, a man capable of writing deep poetry, was more human than we will ever know.

By divine chance, Akhenaten called for “living in truth”21 and figured out things the rest of the world had either forgotten or didn’t care about. This knowledge made him dangerous to the Shemsu Hor. But because he had the courage to flaunt this knowledge in their faces and abruptly attempt to put them out of business, he became a target for assassination. He managed to have an excellent family life in a fabricated society that created the world’s most groundbreaking art for at least ten years—that is an absolute miracle. Seeing his family thrive in his beautiful city and knowing he defeated the Brotherhood of the Snake, if only for a brief moment in time, brought him great joy and offered hope to humanity that a better life was possible.

His palaces were raided, and his army had turned against him. With no regrets, he waited for the butchers to eventually storm Amarna and chop off his head. Akhenaten’s body perished in the unknown sands of the Egyptian desert. Considering how much the people and the Shemsu Hor hated him, it’s not surprising that no evidence of his body survived. This once-great pharaoh, who tried to bring back the indigenous teachings, was left for dead without a tomb or burial relics.

But Egyptology tries to teach that Akhenaten’s body was found in tomb KV55 in 1907 and that he’s actually Tutankhamen’s father! These are the usual sleight-of-hand magic tricks with doctored-up “proof ” that Egyptologists like to pass off as the truth so that we do not stumble, even by accident, across what really happened.

It makes sense that before the Shemsu Hor came to kill him, Akhenaten wanted the world to know the true face of these ancient reptilian overlords, so he had sculptures of his face carved with serpentine features. That these relics even survive is another miracle, as all of Akhenaten’s images and any works pertaining to him or his family were obsessively erased from history. His temples were demolished and his throne was passed on to other pharaohs, who immediately restored the gods of the Amun priesthood and handed power back to the Brotherhood of the Snake.

Figure 8.13. Interior of a tomb at Amarna. Notice the advanced architecture in a city that supposedly was constructed in only five years. From Gaston Maspero, History of Egypt, vol. 5.

His bloodline in Egypt would ultimately be destroyed as well, and his ideas of one sun god or son of god would sleep soundly for another thousand years before morphing into modern Christianity. Flinders Petrie, one of the original excavators and discoverers of Amarna and a person responsible for shedding light on Akhenaten’s legacy, summed up the man beautifully:

His affection is the truth and as the truth he proclaims it. Here is a revolution in ideas! No king of Egypt, nor in any part of the world has ever carried out his honesty of expression so openly . . . Thus in every line Akhenaten stands out as perhaps the most original thinker that ever lived in Egypt, and one of the great idealists of the world.22

Akhenaten lost the battle, but he won the war, for the art that he left behind is truthful and the third eye cannot be fooled because the truth is in the art. The Brotherhood of the Snake returned to power in the wake of Akhenaten’s death and slowly began to steer the course of history to their projected path, minus the slight delay caused by the young rebel pharaoh.

Over time the Brotherhood split into different warring factions and eventually spawned the Knights Templars, the Freemasons, and the Knights of Malta, among other secret orders. At this point the Brotherhood of the Snake is represented through the works of the Illuminati, a collection of elite families and a committee of three hundred23 involved in banking and corporate dominance with the goals of bringing about the New World Order ruled by a form of global government. The large number of Egyptian symbols used by these Illuminati fronts are clues to understanding just how far back these rulers go. Although they are still in control at most levels through bloodlines, it’s not likely that any of the reptoid traits or features have survived.

Figure 8.14. Akhenaten. Courtesy of Gérard Ducher.

Professor Walter Emery, an archaeologist with over forty years of field research experience found evidence that the Shemsu Hor existed in northern Egypt. Emery made a strange discovery one day while digging in Saqqara in the 1930s. After spending weeks excavating in the dry desert air, Emery cleared off the dirt and stared down at skeletons that immediately challenged everything he had been taught about ancient Egypt.

A speaker of five languages and internationally renowned, the maverick French Egyptologist Antoine Gigal writes that, by a stroke of luck, Emery

found in certain tombs the remains of people who lived in pre-dynastic times in the north of Upper Egypt. The features of these bodies and skeletons are incredible. The skulls are of abnormal size and are dolichocephalic, i.e. the cranium as seen from above is oval, and is about 25 percent longer than it is wide. Some skulls show no sign of the usual sutures. The skeletons are larger than the average for the area and especially the skeletal frame is broader and heavier. He did not hesitate to identify them with the “Followers of Horus” and found that in their lifetime they filled an important priestly role. With regard to the long-headed skulls, it seems that it is not a prehistoric lineage of evolution but rather a lineage coming from a cycle of civilization from before the Flood. It is therefore asserted that there once existed an antediluvian race that has been found here and there all over the world, a race that had a naturally elongated conical skull.24

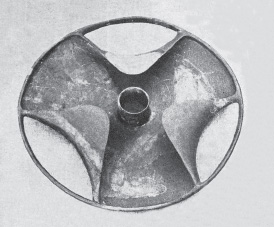

Figure 8.15. In addition to the skulls, Emery also discovered the infamous tri-lobed “schist” bowl—further evidence of highly advanced technology—near where he unearthed the skulls. From Walter B. Emery, Great Tombs of the First Dynasty, vol. I, 1949.

More links to the mysterious Shemsu Hor were found in Iraq at an archaeological site dubbed Tell Arpachiyah, a prehistoric city situated about five miles from Nineveh. It was excavated in 1933 by Max Mallowan and his mystery novel–writing wife Agatha Christie. The pair sifted through numerous graves of the strange Halaf and Ubaid. These two ancient neolithic cultures can be dated as far back as 4600 BCE, and like Emery’s discovery in Egypt, some skeletons of the Ubaid had strange, elongated skulls.25

The Ubaid cemetery and the surrounding archaeological area revealed other astonishing relics associated with the Shemsu Hor, including pottery with serpent-headed women and the most bizarre of all ancient statues—figurines with clear reptoid facial features and elongated skulls (see plate 23). But the mystery of these misshapen skulls isn’t only peculiar to the Shemsu Hor; it also applies to Akhenaten’s family, depicted in the odd images, busts, and sculptures left behind, revealing a legacy of elongated skulls (see plate 24).