China’s Search for Security grew out of a previous work called The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress, which was published in 1997.1 We set out to produce a revised and updated edition of that book, but China’s position in the world has changed so much that we ended up with what is almost entirely a new book. The analytical approach remains the same: we look at China’s security problems from the Chinese point of view in order to analyze how Chinese policymakers have tried to solve them. The basic conclusion also stands: China is too bogged down in the security challenges within and around its borders to threaten the West unless the West weakens itself to the point of creating a power vacuum.

In other respects, however, China’s position in the world has changed. In 1997, it was a vulnerable country, fielding a foreign policy that was mainly defensive and aimed at preventing domestic instability, avoiding the loss of historically held territories such as Taiwan and Tibet, and reconstructing strained relations with potentially threatening powerful neighbors such as Japan, Russia, and India. It had no major interests or significant means of influence in parts of the world beyond its immediate periphery. It was not an actor of consequence in Europe, North or South America, Africa, or the Middle East.

But the 1997 book predicted that things would change, saying, “China is the largest and economically most dynamic newly emerging power in the history of the world. It intends to take its place in the next century as a great power.”2 That century has arrived, and China has fulfilled its intention. Great power is a vague term, but China deserves it by any measure: the extent and strategic location of its territory, the size and dynamism of its population, the value and growth rate of its economy, its massive share of global trade, the size and sophistication of its military, the reach of its diplomatic interests, and its level of cultural influence. It has become one of a small number of countries that have significant national interests in every part of the world—often driven by the search for resources—and whose voice must be heard in the solution of every global problem. It is one of the few countries that command the attention, whether willingly or grudgingly, of every other country and every international organization. It is the only country widely seen as a possible threat to U.S. predominance.

It is easy to forget that China’s rise was what the West wanted. Richard Nixon laid the groundwork for the policy of engagement by arguing in 1967, “[W]e simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors. There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation.”3 He launched the engagement policy with his historic visit to China in 1972. Every American president since then has stated that the prosperity and stability of China are in the interest of the United States.

Engagement was a strategy designed to wean China from Mao Zedong’s pursuit of permanent revolution by exposing the country to the benefits of participation in the world economy. Over the course of three decades, the West opened its markets, provided loans and investments, transferred technology (with a few limits related to military applications), trained Chinese students, provided advice on laws and institutions, and helped China enter the World Trade Organization (WTO) (although negotiating hard over the conditions of China’s entry; see chapter 10). American and more generally Western support had incalculable financial and technological value to China, and it is not an exaggeration to say that Western support made China’s rise possible.

Seldom has the admonition “be careful what you wish for” been so apt. At home, China did abandon Maoist radicalism, but it did not democratize. Instead, economic growth strengthened the one-party dictatorship’s hold on power. Abroad, China took its place as a full player in the global system with a stake in the status quo, as the engagers intended. But now Americans wonder whether a strong China poses a strategic threat.

Thirty-five years of rapid economic growth were bound to produce some shift in relative power just by bulking up Chinese resources. But China’s rise turned out to be all the more dramatic because of its competitors’ weaker trajectories. While China surged, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the successor Russian government struggled to define an international role. Japan stagnated economically and vacillated between accepting security dependence on the U.S. or taking more responsibility for its own defense. India engaged less deeply than China with the world economy and focused most of its security energy on its nearby enemy, Pakistan. While China cultivated mutually cooperative relations with any country that was willing, the U.S. vitiated the advantages of its status as the world’s only superpower with a series of wars and confrontations that weakened rather than strengthened its global influence. For all these reasons, the shift in China’s relative power has been more striking than it otherwise might have been.

These developments have given rise to two interlinked debates over Chinese foreign policy. First, is China an aggressive, expansionist power with enough resources to overwhelm its neighbors and create a “Chinese century” in which China will “rule the world,” or is it a vulnerable power facing numerous, enduring security threats?4 We argue controversially that vulnerability remains the key driver of China’s foreign policy. That is why the subtitle of the previous book, The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress: China’s Search for Security, takes its place as the title of this new volume. The main tasks of Chinese foreign policy are still defensive: to blunt destabilizing influences from abroad, to avoid territorial losses, to moderate surrounding states’ suspicions, and to create international conditions that will sustain economic growth. What has changed is that these internal and regional priorities are now embedded in a larger quest: to define a global role that serves Chinese interests but also wins acceptance from other powers.

We add that last qualifying phrase because defining a role for a rising great power is not a unilateral process. A decade ago it was largely a matter for China itself to determine how to provide for its own security (except for its management of the Taiwan issue, on which the U.S. asserted a right to limit Chinese options; see chapter 4). But as China’s core interests evolve from regional to global, they intersect more and more with those of the other major powers, leading to greater possibilities for both cooperation and conflict. As China’s influence increases, so do other powers’ efforts to channel or constrain that influence. Rising power brings not only new scope for action, but new checks. China will have to define its role through interactions that are inevitably contentious with other actors and that may turn conflictual, which makes it more important than ever to understand what drives Chinese foreign policy.

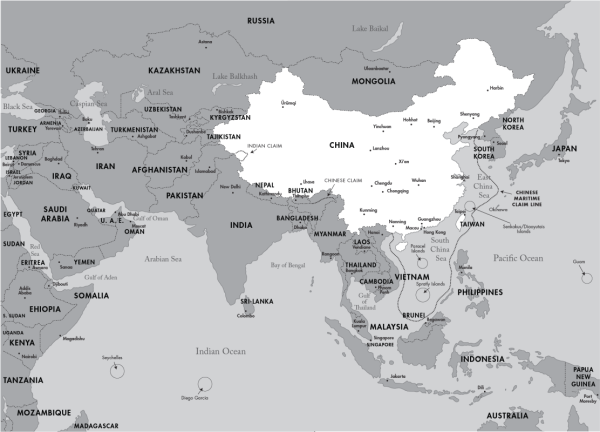

That is why we start in chapter 1 with the fundamentals of geography and demography—where China is on the map, who lives there, how its population is distributed, and who its neighbors are. The relevance of these facts is emphasized by the approach to foreign policy analysis called “geostrategic” or “classical realism,” which says that the world does not look the same from every point on the map. The Chinese are not where we are, they are not who we are, and we have to look at their situation to understand their actions. China is not special in the fact that geography matters; what is special for China—as for every other country—are the specifics of its geopolitical situation.

Chapter 1 also takes account of culture and ideology. People think and talk about their national situation and national interests in terms that are meaningful and understandable to them. We need to know the concepts they use in order to understand the discourse. Paying attention to culture does not mean cultural relativism: a country’s core security interests are intelligible to an analyst from any culture. But to understand how they are being talked about requires a process of interpretation.

The causal path from facts on the ground to policy outputs runs through actors and institutions—the people who make policy and the institutions within which they do so. These people and institutions are discussed in chapter 2. Sometimes the connection is straightforward. Sometimes it is distorted by cognitive factors (misinformation, miscalculation), perceptual factors (erroneous guesses about others’ motives), and value commitments (preferences for values besides security) or by institutional habits and structures, domestic political needs, and leadership shortcomings. Thus, we may sometimes fail to find an interest-based explanation that makes sense of a particular element of foreign policy. When that happens, we turn to other factors to explain why China—like other countries—sometimes adopts policies that apparently do not serve its national interests. As we show, this happened relatively rarely in China even during the Mao period and has happened rarely since then. Chinese foreign policy has usually made sense as part of a search for security. Why Chinese policy should more often be more interest based than some other countries’ policies is a question we explore in several places, especially in the first four chapters.

CHINESE FOREIGN POLICY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THEORY

The second debate occasioned by the rise of China is whether its policymaking processes are driven more by culture, nationalism, and resentment over a “century of humiliation” or more by a realistic calculus that seeks to match available resources to concrete security goals. On this question, we lean, again controversially, to the position that Chinese foreign policymaking is more often than not rational. To be sure, China’s behavior can be puzzling at first glance. Why did China formally ally itself with the Soviet Union in 1950, then split with it ten years later? Why did it move from antagonism to rapprochement with the U.S. in 1971? Why does China pursue disputes with Japan over historical issues at certain times and not at others? Why did China seek to promote unification with Taiwan by counterproductively building up a missile threat to the island from the early 1990s onward and threatening to use military force if Taiwan were to “secede”? Why does China cooperate with “rogue states” such as North Korea, Sudan, Iran, and Burma? What were Beijing’s aims in forming the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)? What are its territorial ambitions in the South China Sea?

Every decision, no doubt, has a back story—bureaucratic politics, misperception, international signaling—that we are usually not going to know because it is confidential. But such actions and policies also make larger patterns that we as observers are able to discern. We find that the puzzles of Chinese foreign policy most often yield answers through the insights of a theory called “realism,” which suggests that foreign policy is driven by national self-interest—in turn meaning strategic and economic advantage, or what we call “security” in this book. For all its vastness and resources, China has extensive vulnerabilities throughout its security environment, a theme we develop in chapter 1. Because of rapid social change and ethnic diversity, it is insecure within its own borders; around its periphery, it has a history of wars with many of its neighbors (Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, India, Russia); in each neighboring region, it faces factors of instability; and in the regions beyond Asia, China’s economic security is subject to forces beyond its control. The theory of realism says that these challenges set the agenda for Chinese foreign policy.

The political science field of international relations also presents two other useful perspectives on how to understand the drivers of a country’s foreign policy: constructivism, the theory that a state’s interests as well as its strategies to achieve these interests are constructed through actors’ use of perceptions, values, and ideas to understand and react to their situations; and institutionalism, a theory that emphasizes how states, once they engage themselves in institutional arrangements (such as treaties and international organizations), become constrained by these sets of rules in patterns of “complex interdependence” as a result of the benefits they gain from using such prearranged channels to work with other states toward common goals. We also draw occasionally from a fourth theory in the field, liberalism, which draws attention to the role of a country’s domestic interest groups in making foreign policy. But the theory does not tell us much about China because, as we argue in chapter 2, most foreign policy issues in China are managed by a small elite with little interference from other political institutions and social forces. Foreign economic policy is a partial exception, where domestic interests help shape foreign economic policy to a greater extent than in other fields (chapter 10). Of course, the role of social interests in Chinese foreign policy may grow in the future. We use these theoretical traditions to nuance our mostly realist analysis in the belief that the various approaches are not mutually exclusive.

Realism tells us that security is the ability to maintain effective control over one’s own political regime, economy, way of life, borders, and population. The means for achieving security are various kinds of power. The Western literature on Chinese foreign policy pays attention to five elements of Chinese power: military power;5 economic power (including trade, investment, access to markets, access to resources, and foreign exchange holdings);6 interdependence–power (China’s impact on the environment, public health, and other global issues beyond its own borders);7 diplomatic power (China’s role in such settings as the United Nations [UN] Security Council, in the talks over Korea, and in negotiations that involve Iran, Sudan, and other problem states);8 and soft power (the influence of Chinese values and of China’s political and economic models, international interest in Chinese culture and language, and so on).9 For their part, Chinese analysts use a notion of “comprehensive national power,” which has various components and which they tend to assess as a package.10 We pay attention to all these elements of power throughout the book and discuss three of them in detail in part IV.

We agree with constructivists that security is a dynamic rather than a static concept. In China’s complex environment, the decision makers’ concept of their nation’s security interests must adapt to changing information and opportunities. In the 1950s, Chinese leaders took the U.S. as their main enemy, and in the 1960s the USSR; in the 1970s, they positioned themselves as leading the Third World against two hegemons in the search for a world of peace and stability for development; then in the 1990s they seemed again to see the U.S. as the main threat to their security; and now, at a time when the U.S. is perhaps more unilateralist in its behavior and has more military forces near China than ever, they seem to believe that the two countries can find a way to balance one another and cooperate to achieve mutual interests.

Constructivism says that policy decisions are influenced by the leaders’ perceptions and values and the institutions through which they make and implement decisions. In chapter 2, we look at ideas and institutions involved in making foreign policy, including factional and bureaucratic politics and central–local relations.11 We find that an important feature of Chinese foreign policymaking is that it is centralized and coordinated, allowing even imperfect human institutions to pursue realist policies more often than not.

Realism argues that any two powers whose security interests intersect (which can happen in terms of territory or in terms of economic interests or in terms of power-projection potential) can become caught in a dynamic that Robert Jervis has identified as the “security dilemma.”12 The dilemma occurs when one country’s attempt to increase its ability to protect itself diminishes the security of the other country by changing the relative balance of power. This dynamic may easily come into play in the Sino–American relationship as China’s rise in its own region intensifies the intersection of its security perimeter with long-established American positions throughout Asia and as China’s economic outreach under conditions of globalization brings it into increasing interaction with the already established economic presence of the U.S. and its European and Japanese allies in many parts of the world.

Yet institutionalist scholars have pointed out that even while competition increases, states can also experience “gains to cooperation” in the international system.13 As an example, the growth of the Chinese economy has benefited the U.S. economy by providing a market for American goods, supplying cheap, high-quality consumer products, and soaking up U.S. government debt, among a multitude of ways. Cooperation on public health and environmental issues similarly creates mutual benefit. To be more than fleeting, gains have to be institutionalized in the form of international agreements and organizations. The China–America relationship illustrates these dynamics: engagement enmeshed China in a series of institutions that it has come to value for their benefits. China’s record of compliance with many international regimes (trade, investment, arms control) has moved from nonexistent to strong in the course of a few decades; in other regimes, China is engaged but lags in compliance (intellectual property protection, human rights). The theory of institutionalism is compatible with realism because cooperation may increase an actor’s power and security. It is compatible with constructivism because actors have to perceive the opportunities for gain, create or learn the rules, and establish the domestic and international bureaucracies needed to harvest the gains—a set of processes scholars refer to as “learning” or “socialization.”

Cooperative gains in turn, however, can generate new frictions over the distribution of costs and benefits. How much American interference does China have to accept in order for its products to meet American health and safety standards? And are such standards fair? How much stake does each side have in the other’s management of foreign exchange rates when the two are doing a huge volume of trade? What does China give up in informational autonomy when it cooperates with the World Health Organization (WHO) to fight this or that contagious disease? Who pays what portion of the cost of halting global climate change? Such frictions can be intense but need to be placed in perspective as part of the process of cooperating.

Military interests may also converge, as in the case of the shared U.S. and Chinese interest in the denuclearization of Korea. Yet the Korea example also suggests that such overlaps are seldom as encompassing or protracted as the compatibilities in economic, public-health, or global-order issues. Although neither China nor the U.S. wants a nuclear Korea, they vie for long-term predominance on the peninsula. So cooperation on a near-term goal is limited by different preferences about how that goal is to be achieved and by a divergence of interests in the shape of the ultimate outcome.

When geostrategic conflicts of interest are difficult and intense, they tend to find parallel expression as cultural conflicts, a point important to constructivists. A good example of this dynamic has occurred in China–Japan relations. Most scholars of this relationship consider it puzzling that Sino–Japanese relations are as bad as they are and usually explain the puzzle by referring to history and culture or to nationalism seen as an ungovernable collective emotion or as a creature of political entrepreneurs.14 The more realism-centered explanation that we offer in chapter 5 is that these two militarily powerful and geographically close countries have overlapping, competitive core security interests in the East China Sea, the Senkaku Islands, the Sea of Japan, the Korean Peninsula, the Russian Far East, the Taiwan area, and the broader Pacific as well as with respect to the security of sea lanes through the South China Sea and beyond. Neither has a solid defense against the other, and both stand to lose in the event of military conflict. These enduring geostrategic facts have generated a long history of distrust and contention. In chapter 5, we interpret conflicts over history textbooks and visits to religious shrines as expressions of this underlying security dilemma, thus combining realist and constructivist perspectives.15

According to the theory of realism, as power expands, ambitions expand with it.16 But power cannot expand infinitely because power is relational: the other side always has some way to resist. This relationship makes it meaningless to say in the abstract how much power China (or any other actor) has. One needs to evaluate Chinese power in relation to the power of potential allies and adversaries and with an eye to the usability of power in particular situations. The bare fact that China’s power is expanding does not tell us where it will expand (Southeast Asia? Central Asia? Africa? Latin America?) or how (militarily? economically?) or how it will be used. For example, as Thomas Christensen has shown, even though the Chinese military remains inferior to the American military, it has the capability to pose serious challenges to U.S. armed forces operating in the western Pacific.17 However, economists have argued that even though China as of April 2010 held nearly a trillion dollars in U.S. Treasury bills and other dollar-denominated assets, it could not use this resource to cause serious damage to the American economy because the attempt to do so would exact too high a cost on China itself. So power is not fungible: it can be exerted only in specific ways based on a country’s geostrategic position, assets, and vulnerabilities as well as on the assets and deployments of those against whom it is being used.

THE GREAT WALL AND THE EMPTY FORTRESS

The earlier book from which this one stems, The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress, refers in its title to two elements of the Chinese strategic tradition that are still worth noticing.

The Great Wall is an extensive network of battlements and fortifications along the northern edge of China’s demographic heartland. Various parts of the network were constructed by different dynasties over the centuries—one of a number of strategies adopted by different rulers to protect the heartland from invasions by Central Asian horse-mounted armies.18 The Great Wall is in part a symbol of weakness because it signals susceptibility to invasion, but also in part a symbol of strength because it represents the economic and cultural superiority of the land within the wall and its productive denizens’ ability to deter invasion with feats of engineering and vigilance.

Today’s invaders are more likely to be department store buyers, venture capitalists, tourists, and foundation officers than mounted nomads, but China is no less concerned to control their influence. The methods of protection are now more virtual than physical—among them a nonconvertible currency, regulatory obstacles to full foreign access to the domestic economy, repression of independent civil society organizations that have foreign connections, active police surveillance of foreigners and foreign-connected Chinese, and the so-called Great Firewall that restricts the Chinese Internet’s access to the international Internet.

Geographically as well, China still lies open to invasion or dismemberment, even though no country currently shows an appetite for such an adventure. Traditional invaders had the advantages of mobility, concentrated force, and explosive violence. But if they breached the northern fortifications, they faced decades of resistance before they could conquer the whole of China, and then they were able to stabilize their rule only by assimilating themselves to Chinese civilization, as did the dynasties of the Yuan (1271–1368) and the Qing (1644–1911). No foreigners after the Manchus (the ethnic group that established the Qing dynasty) have conquered China. China ceased to be vulnerable to invasion not because it had strong enough border defenses to keep out a determined aggressor, but because it threatened to bog down the invader so badly that neither the nineteenth-century Western imperialists nor the twentieth-century Japanese militarists could take over the country. We show in chapter 3 that under Mao this quagmire threat was sufficient to deter both the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Today, Chinese policymakers continue to be more concerned with defending their territory than with expanding it. China maintains a near-seas navy, strong border troops, nationwide anti-aircraft capabilities, and a nuclear deterrent. As we detail in chapter 11, these assets are deployed to defend China’s territorial holdings and its unresolved territorial claims. Even the posture of Chinese nuclear forces is deterrent rather than coercive. But we also discuss whether China is building the capability for force projection in the future and, if so, for what contingencies.

The previous book used the “empty fortress,” like the Great Wall, as a symbol of mixed weakness and strength. In a famous chapter in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (chapter 95), a great fourteenth-century novel about second- and third-century civil wars, the strategist Zhuge Liang is outnumbered in the defense of a walled city. He lowers the military banners, orders his troops to hide, opens the gates, and sunbathes on the ramparts in view of the enemy army. Seeing him so unconcerned, they conclude that the city must be well defended and that Zhuge19 is trying to entice them into an ambush. So they decamp without attacking.

The ancient story symbolizes Chinese strategists’ ability to magnify limited resources, appear stronger than they are, and deter enemies from attack or subversion while biding their time to build up power. Even after China’s rise, that reading of the symbol remains relevant today. China’s power is real, but foreigners are prone to evaluate the country as even more formidable than it really is. In comparison, the U.S. has a vastly larger economy and stronger military, with true global reach. Japan has a better-financed, more technologically advanced military. India, with a similar-size population and territory, albeit a smaller gross domestic product (GDP), has a more advantageous geostrategic position and a better-equipped navy and air force. And the European Union (EU) has a large population, a continental strategic position, a larger GDP, and more advanced technology. Why is it that, except for the U.S., these other powers languish, relatively speaking, in the global shadows, generating neither the respect nor the fear that China does?

One reason, which we explore in chapter 1, is China’s uniquely sensitive geostrategic position, at the hinge between Eurasia and the Pacific, with a decisive role in six complex and important regional subsystems that we label Northeast Asia, continental Southeast Asia, maritime Southeast Asia, Oceania, South Asia, and Central Asia. A second reason is, however, the ability of China’s foreign policy leadership to control information and perception sufficiently to create a mystique of strength. Their skill at doing so has some disadvantages, such as drawing attention to China as America’s primary potential rival. But its advantage is to produce more deference from other countries than China’s objective power resources warrant.

China’s power, however, if sometimes overhyped, is no illusion. It was not China’s weakness but its burgeoning strength that the late leader Deng Xiaoping instructed his colleagues to hide when he gave the four-character instruction, “taoguang yanghui” (Hide our light and nurture our strength). After Deng’s death in 1997, China continued his reassurance strategy—telling other countries that its foreign policy goals are limited, seeking resolution or postponement of territorial disputes with most neighbors, acceding to more and more treaties on arms control, human rights, and the environment. Are these cooperative gestures signals of China’s maturation into a status quo power that supports the global rules of the game? Or are they tactics to lull others into complacency while China builds up its capabilities to challenge the system? We grapple with these issues in chapter 13.

In the end, we doubt that China’s leaders today have a fixed blueprint for the future. They will define a global role for China depending not only on their own goals and behavior, but also on how others around the world interact with them. That means that we can afford to be optimistic in believing that there are no inevitable conflicts of geostrategic interest between China and the West, but we must also be realistic in acknowledging that pathways to cooperation in international affairs are found only through friction and contention, if they are found at all.

The ancient Chinese military handbook The Thirty-Six Stratagems ends with the following quip: “Of the thirty-six stratagems, running away is the best.” But China is not going to run away, and we cannot run away from it. It is going to continue to be there, and the rest of the world will have to deal with it. The purpose of this book is to understand what drives Chinese policy—to analyze the world as much as possible as Beijing policymakers analyze it. The attempt to understand Chinese policy from the viewpoint of China’s place in the world should be read as neither approval nor disapproval of that policy. Our analysis should be equally useful for those who want to accommodate Chinese goals, for those who want to frustrate them, and for those who seek just to understand them.