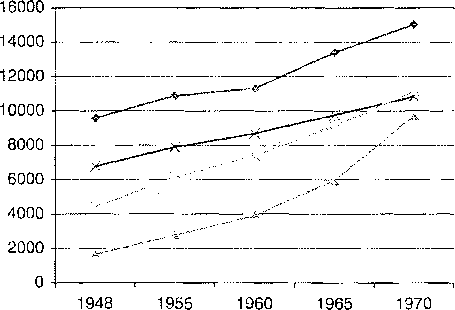

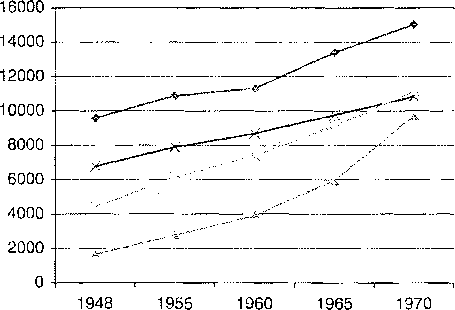

Figure 11.1 Real GDP per capita during the period of the Global Plan.

It is history’s wont to turn unimaginable developments into seeming inevitabilities. At war’s end, with Germany still smouldering, divided into different occupation zones, devastated, despised by the whole world; with Japan still numb at the humiliation of surrender, wounded by the nuclear attacks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, coming to terms with the immense death toll on the East Asian and Polynesian battlefields, and labouring under an American occupation... the writing of the eventual post-war script was definitely not on the wall!

No one had an inkling of the role that these once proud but now ruined countries would be playing in a few short years. The notion that Germany and Japan would become the pillars of the new Global Plan was as outlandish as it was outrageous. And yet, it was the notion on which the New Dealers converged around 1947. How did that choice transpire? The answer is: gradually.

Box 11.2 The Global Plan’s New Deal architects

As we have referred to the New Dealers extensively (see Sections 8.1 and 9.2), we only need to turn the spotlight on the four members of the administration who played the most crucial role in fashioning the new post-war Global Plan which began with the brief to create, tabula rasa, two new monetary pillars for the dollar: one in Europe (the Deutschmark) and one in Japan (the Yen). The four men in question were, importantly, also the architects of the Cold War:1

• James Forrestal, Secretary of Defence (previously Secretary of the Navy)

• James Byrnes, Secretary of State

• George Kennan, Director of Policy Planning Staff at the State Department and renowned ‘prophet’ of Soviet containment

• Dean Aches on, Leading light in all major post-war designs (the Bretton Woods agreement, the Marshall Plan, the prosecution of the Cold War, etc.) and Secretary of State from 1949 onwards.

These four men shared a common pragmatic view that was forged during the war I and emerged under the shadow of the 1930s experience with flagging domestic aggregate demand, the failure to coordinate a unified response by the different capitalist i centres against the Great Depression and, not least, the crucial role of military-induced ! production in keeping a capitalist economy effervescent. They also shared a contempt I for economic theory and a conviction that the post-war economy should be run in a I manner not too dissimilar to the successful running of the War Economy: by a combi- j nation of non-economist technocrats (the Scientists of Chapter 8) and New Dealer \ policymakers. \

Note

1 See also Schaller (1985).

At first, it was inconceivable that Britain would not be a central pillar of the Global Plan. However, the fiscal weakness of the British state, its fast declining industry, the 1945 electoral victory of the Labour Party, the clear reluctance to come to terms with the impending End of Empire and, last but not least, the slide of the Pound to eventual non-convertibility, alerted the New Dealers to the possibility that Britain was better left out of the Global Plan. Britain had to experience the Suez Canal trauma in 1956, not to mention the undermining of its colonial rule in Cyprus by the CIA throughout the 1950s, before realising this turn in US thinking.1

Once Britain was deemed ‘inappropriate’, its sense of having won the war being part of the problem, the choice of Germany and Japan increasingly appeared entirely logical: both countries had been rendered dependable (thanks to the overwhelming presence of the US military), both featured solid industrial bases, both offered a highly skilled workforce and a people who would jump at the opportunity of rising, Phoenix-like, from their ashes.: Moreover, they both held out considerable geostrategic benefits vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.

Nonetheless, that realisation had to overcome a great deal of resistance grounded on an opposite instinct: the urge to punish Germany and Japan by forcing them to deindustrialise: and return to an almost pastoral state from which they would never again find it possible to launch an industrial-strength war. Indeed, Harry Dexter White, the US representative at Bretton Woods (see Box 11.1), had advocated that Germany’s industry be effectively removed, forcing German living standards to fall to those of its less developed neighbours. In 1946, the Allies, under the auspices of the Allied Control Council, ordered the dismantling of steel plants with a view to reducing German steel production to fewer than six million tons annually, that is around 75 per cent of Germany’s pre-war steel output. As for car production, it was decided that output should dwindle to around 10 per cent of what it was before Germany invaded Poland.

Things were a little different in Japan. Administered as an occupied country by one man. General Douglas Mac Arthur or SCAP (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers), United States policy could be dictated directly, unencumbered by the need to negotiate with other allies (as was the case in Germany). MacArthur decided that Japan should not go through an equivalent process to de-Nazification and went to great lengths to exonerate the Emperor and the Japanese political, military and economic elites. Nevertheless, during the first two years of occupation, he too had to argue vigorously with Washington policymakers against punishing Japan by destroying, or severely circumscribing, its industrial base.

The sea change against the idea of flattening Germany’s and Japan’s industrial sectors was aided and abetted by the increasing tension between the United States and the Soviet I Inion. It was George Kennan’s Long Telegram from Moscow in February 1946 (first mentioned in Section 8.1), and the inexorable rise of the Cold War spirit, that created the circumstances for a change of heart about Germany. The pivotal moment came when President Harry Truman, who succeeded F.D. Roosevelt when the veteran President died in April

1945. announced his notorious Doctrine in 1947.

The impetus for the Truman Doctrine to contain Soviet influence, in accordance with Kennan’s Long Telegram, came from the streets of Athens in December 1946. It was there that left-wing, pro-Soviet partisans clashed with the British Army and its local allies (many of them ex-Nazi collaborators) thus setting off the awful Greek Civil War of 1946-49. Soon after, the British discovered that they could not pursue that war successfully, especially in the circumstances of Britain’s increasing financial difficulties at home. They thus called upon the United States (which were playing a commendably neutral role until then) with an urgent request that the Americans step into the British Army’s shoes and pursue the Greek Civil War.

Thus, the United States took its baptism of fire on the mountains of Greece, in a clash-by-proxy with the Soviet Bloc and its allies. A few months later, the proxy war nearly turned into a direct confrontation when the Western occupiers in West Berlin tussled with the Soviet occupiers of East Berlin; a mêlée which led to a long air-lifting of supplies from Western Germany to West Berlin, over the lines of the Red Army. The Cold War had almost begun. What it required was an official declaration.

The official declaration came on 12 March 1947 when President Truman delivered a famous speech in which he committed substantial sums, arms and political ammunition against the Greek partisans. It was to be the first instalment in a general drive to contain the Soviet Union and its sympathisers throughout Europe and Asia. The second instalment came in the form of the Marshall Plan, (see Box 11.3) a large financial injection into the economies of Western Europe which succeeded in creating the circumstances for the enactment of the Bretton Woods agreement that had been struck back in 1944.

Box 11.3 From the Truman Doctrine to the Marshall Plan

On 12 March 1947, President Hairy Truman unveiled his Doctrine, pledging military and economic aid to the Greek government in its war against the resistance fighters who had previously opposed the Nazi occupation. The bill for this monstrous civil war, that still haunts Greeks today, was 400 million dollars. However, it was only the beginning of a massive intervention to stabilise Europe and render it safe for the Global Plan. On 5 June 1947, Truman’s Secretary of State, George Marshall addressed a Harvard audience with a speech that marked the beginning of the Marshall Plan, a massive aid package that was to change Europe.

Its formal name was the European Recovery Program (ERP), the brainchild of the Global Plan’s architects mentioned in Box 11.2. The fact that it was meant as a game-changing intervention, the purpose of which was clearly to establish a new world order in order to save capitalism’s bacon, can be gleaned from some key words employed by Marshall in that important speech: ‘the modern system of the division of labour upon

which the exchange of products is based is in danger of breaking down’. The point of j the Marshal] Plan was, put simply, to save global capitalism from collapse, |

The Marshall Plan involved not only a great deal of money but also vital institii- ! tions. On 3 April 1948, Truman established the Economic Co-operation Administration i and 13 days later the United States and its European allies created the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), with a remit to work out where to channel the funding, under what conditions and to which purpose. The first Chair of the OEEC (which later, in 1961, evolved into what we know today as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the OECD) was Robert Marjolin, one of the three participants in the Harvard reading group dedicated to understanding Keynes’ General Theory (see Section 8,1), j

During the first year of the Marshal! Plan, the total sum involved was in the order j of 5.3 billion dollars, a little more than 2 per cent of the United States’ GDP. By 31 December 1951, when the Marshall Plan came to an end, 12.5 billion dollars I had been expended. The end result was a sharp rise in European industrial output 1 (about 35 per cent) and, more importantly, political stabilisation and the creation of sustainable demand for manufacturing products, both European and American.

Not all of the New Dealers, it must be said, accepted the premise that the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan was a one-way street, For instance, Henry Wallace, the former Vice President and Secretaiy of agriculture, who was fired by Truman for disagreeing with the Cold War’s imperatives, referred to the Marshall Plan as the ‘Martial Plan’, warning against creating a rift with America’s wartime ally, the Soviet Union, and remarking that the conditions under which the Soviet Union was invited to be part of the Marshall Plan were designed in order to force Stalin to reject them (which, of course, Stalin did), A number of academics of the New Deal generation, amongst them Paul Sweezy and John Kenneth Galbraith (also mentioned in Section 8.1), also rejected Truman’s cold-warrior tactics. However, they were soon to be silenced with the witch-hunt orchestrated by Senator Joseph McCarthy and his House Committee on Un-American Activities.

As important as the dollarisation of the European economy was for restoring markets and reinvigorating industry, the Marshall Plan’s relatively unsung, but equally significant, legacy was the creation of the institutions of European integration, from which the greatest beneficiary was to be the continent’s defeated nation: Germany!

The Americans’ condition for parting with about two per cent of their GDP annually was the erasure of intra-European trade barriers and the commencement of a process of economic integration that would increasingly be centred around Germany’s reviving industry. In this sense, the Marshall Plan can be fruitfully thought of as the progenitor of today’s European Union. Indeed, from 1947 onwards the US military (and in particular the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon) called for the ‘complete revival of German industry, particularly coal mining’ and pronounced that the latter was acquiring ‘primary importance’ for the security of the United States.

However, it would be a while longer before the rejuvenation of Germany’s industrial might would become an openly declared aim; for even as the Marshall Plan was unfolding, the dissolution of German factories was continuing. It is indicative of the period that the

German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, pleaded in 1949 with the Allies to put an end to factory liquidations.

The most resistant of the Allies to the notion of an industrialised post-war Germany was, -is one might have expected, France. The French demanded that the agreement of 29 March

1946, in which the Allies had ruled that half of Germany’s industrial capacity would be destroyed (involving the destruction of 1,500 plants), remained in force. It was. By 1949, more than 700 plants had been disassembled and steel output was reduced by a massive 6.7 million tons.

So, what was it that convinced the French to accept the reindustrialisation of Germany? The United States of America, is the simple answer. When the New Dealers formed the view, around 1947, that a new currency must rise in Europe to support the dollar, and that this currency would be the Deutschmark, it was only a matter of time before the destruction of German capital would be reversed. The price France had to pay for the great benefits of the Marshall Plan, and for its central administrative role in the management of the whole affair (through the OEEC), was the gradual acceptance that Germany would be restored to (mice, courtesy of the United States’ new Global Plan.

in this context, it is useful to think of the Marshall Plan as a foundation of the Global Plan. For as the former was running out of steam, in 1951, it was already passing the baton to phase two of the American design for Europe: integration of its markets and of its heavy industry. That second phase came to be known as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the precursor to today’s European Union. The new institution was soon to provide, as was intended by the New Dealers, the vital space that the resurgent German industry required in its immediate economic environment.

Turning now to the second pillar that was intended to support the dollar on the other side of the Northern hemisphere, the restoration of Japan as an industrial power, proved less problematic for the New Dealers than Germany had. The eastern version of the Global Plan was helped significantly by the onslaught of Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party against Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government army.

The more Mao Zedong seemed to be evading attacks against his guerrillas, and winning the Chinese Civil War, the more General Mac Arthur edged towards a resolution to bolster Japanese industry, rather than succumbing to pressures to weaken it. However, there was a snag: while Japanese industry and infrastructure emerged from the war almost intact (in sharp contrast to Europe’s), Japanese industry was plagued by a dearth of demand. The New Dealers’ original idea was that the Chinese mainland would provide the Yen zone with its much needed vita! space. Alas, Mao’s gains and his eventual victory threw a spanner in those works (see Schaller, 1985; Forsberg, 2000).

General MacArthur understood the problem and tried to convince Washington to embark upon a second Marshall Plan, within Japan itself. However, the New Dealers could not see how enough demand might ever be created within Japan alone, without significant trade links with its neighbours, In any case, at that time they were preoccupied with the struggle to convince Congress to keep pumping dollars into Europe (see Halevi, 2001). However, MacArthur’s luck changed when on 20 June 1950 Korean and Chinese communists attacked South Korea, with a view to unifying the peninsula under their command.

Suddenly, the Truman Doctrine shifted focus from Europe to Asia and the great beneficiary was Japanese industry. Mindful of the difficulty Japan was having to develop its industry, given the lack of consumer purchasing power, the New Dealers sought ways to boost demand within Japan well before Kim II Sung’s escapade in Korea. The latter provided the architects of the Global Plan with the opportunity they had been seeking.

The Marshall-Plan .was initially to last until 1953. But the war in Korea allowed the New Dealers to alter course: they would wind the Marshall Plan down in Europe and shift funds to Japan, whose new role would be to produce the goods and services required by the US forces in Korea - a fascinating case of war-financing of an old foe!

As for the Europeans, the idea was that the first three years of the Marshall Plan dollarised Europe sufficiently and that, from 1951 onwards, cartelisation centred around Germany's resurgent industry, and in the context of the newly instituted ECSC (see Box 11.4), would generate enough surplus for Europe to move ahead under its own steam.2

The United States’ transfers to Japan were quite handsome. From day one, they amounted to almost 30 per cent of Japan’s total trade. And, just as in Europe, the United States did

Box 11.4 From coal and steel to the European Union

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was, technically speaking, a common market for coal and steel linking Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland. Not only did it involve the dismantling of all trade barriers between these countries concerning coal and steel products but, additionally, it featured supra* national institutional links whose purpose was to regulate production and price levels. In effect, and despite the propaganda to the contrary, the six nations formed-a cartel over coal and steel.

European leaders, such as Robert Schuman (a leading light in the ECSC’s creation), stressed the importance of this coming-together from the (pertinent) perspective of averting another European war and forging a modicum of political union. Creating a shared heavy industry across, primarily, France and Germany would, Schuman believed (quite rightly), both remove the causes of conflict and deprive the two countries of the means by which to persecute it.

Thus, Germany was brought in from the cold and France gradually accepted its re-industrialisation; a development essential to the New Dealers’ Global Plan. Indeed, it is indisputable that without the United States guiding Europe’s politicians, cajoling and threatening them, often in one breath, the ECSC would not have materialised. Contrary to the Europeans’ self-adulating narrative (according to which European unification was a European dream made real by means of European diplomacy and because of an iron will to put behind Europe its violent past), the reality is that European integration was a grand American idea implemented by American diplomacy of the highest order. That the Americans who effected it enlisted to their cause enlightened politicians, such as Schuman, does not change this reality.

There was one politician who saw this clearly: General Charles de Gaulle, the future President of France who was to come to blows with the United States in the 1960s, so much so that he removed France from the military wing of N ATO. When the ECSC was formed, de Gaulle denounced it on the basis that it was creating a united Europe in the form of a restrictive cartel and, more importantly, that it was an American creation, under Washington’s influence and better suited to serve what we call the Global Plan than to provide a sound foundation for a New Europe. For these reasons, de Gaulle and his followers voted against the formation of the ECSC in the French parliament.

not just pour money in. They also created institutions and used their global power to bend existing institutions to the Global Plan's will. Within Japan, the United States wrote the country's new constitution and empowered MITT, the famed Ministry for International Trade -ind industry, to create a powerful, centrally planned (but privately owned), multi-sectoral industrial sector. Overseas, the New Dealers clashed with, among others, Britain to have Japan admitted to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (the ancestor of today's World Trade Organisation). The importance of the latter cannot be underestimated, as it allowed Japanese manufactures to be exported with minimal restrictions wherever the United States deemed as a good destination for its new protégé’s goods.

In conclusion, the New Dealers’ central organising principle was that American global heqemony demanded generous augmentation of external sources of both effective demand and stability for the two countries that it would patronise and whose assistance it would seek in order to stabilise world capitalism.3 For this purpose, they took audacious steps to create the Deutschmark and the Yen zones, to provide them with the initial liquidity necessary to restart their industrial engines and to ensure that the political institutions were there that would allow the green shoots to flourish and grow into the mighty pillars that the dollar zone required for long-term support. Never before in history has a victor supported the societies that it had so recently defeated in order to enhance its own long-term power, turning them, in the process, into economic giants.

11.3 The Global Plan’s golden era

Within five years of the initial conception of the Global Plan, two non-dollar currency zones, founded on rejuvenated industrial sectors, had emerged in full supporting roles to the dollar’s unchallenged dominion. Its architects had taken the measure of the task, adopting bold political initiatives, both in Europe and in Japan, to ensure the parallel creation of free-trade areas within these zones. Their mission? To carve out crucial vital space for the real economies ‘growing around’ the new currencies.

Of course, the best-laid plans, or at least parts of them, often end up lying in ruins. Whereas the European free trade zone evolved, as planned, into German industry’s vital space, the Plan came unstuck in the Far East, courtesy of Chairman Mao. What is fascinating, however, is the way in which successive US administrations attempted to make amends in diverse and creative ways.

First, there was the Korean war which, as mentioned above, proved an excellent opportunity to inject demand into the Japanese industrial sector. Second, the United States used its influence over its allies to allow Japanese imports freely into their markets.4 Third, and mast remarkably, Washington decided to turn America’s own market into Japan’s vital space. The penetration of Japanese imports (cars, electronic goods, even services) into the US market would have been impossible without a nod and a wink from Washington’s policymakers. Fourth, the successor to the Korean war, the war in Vietnam, was further to boost Japanese industry. A useful by-product of that murderous escapade was the industrialisation of South-East Asia, which further strengthened Japan by providing it, at long last, with the missing link: a commercial vital zone in close proximity (see Rotter, 1987).

Our argument here is not that the Cold Warriors in the Pentagon and elsewhere were pursuing the New Dealers’ Global Plan with a view to organising world capitalism. While not innocent of the idea, as the heavy involvement of military leaders in the Marshall Plan reveals, they naturally had their own geopolitical agenda. Our point is that, while the generals, the Pentagon and the State Department were putting together their Cold War strategic

plans, Washington’s economic planners approached the wars in Korea and Vietnam from a quite distinct perspective.

At one level, as we claimed, they saw them as crucial in maintaining a continual supply of cheap raw materials to Europe and Japan. At another level, however, they recognised in them a great chance to bring into being, through war financing, the vital economic space that Mao had robbed ‘their’ Japan of. It is impossible to overstate the point we raised earlier (again see Rotter, 1987) that the South-East Asian ‘tiger economies’ (Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore, which were soon to become for Japan what France and Spain were to Germany) would never have emerged without these two US-financed wars, leaving the US as the only sizeable market for Japanese industrial output.

The United States tended to its European and East Asian creations for at least two decades After Europe5 and Japan6 were politically ‘stabilised’ (more often than not by unwholesome means), when the two regions began to take their fledgling steps, Washington extended credit, directly or indirectly, to the German economic zone and its Japanese counterpart so as to enable them to purchase the requisite technology and energy products, fundamentally oil, as well as to attract and utilise (often) migrant labour (see Hart-Landsberg, 1998).

The United States had come out of the war with a healthy respect for the colonised and a short temper towards their European colonisers. Britain’s stance in India, Cyprus, even its incitement of the Greek Civil War (as early as in 1944), was thoroughly criticised by the New Dealers. France too, Flolland and Belgium, were chastised for their ludicrous ambition; to remain the colonial masters in Africa, Indochina and Indonesia, despite the sorry state in which the Second World War had left them.

However, the loss of China, the trials and tribulations of Latin America, the escalation of liberation movements in South-East Asia that tended to coalesce with Mao’s communists (against the French), the stirrings in Africa that gave the Soviet Union an opening into that continent; all these developments enticed the US into developing an aggressive stance against liberation movements in the Developing World which Washington soon came to identify with the threat of rising input prices for its two important protégés: Japan and; Germany.

In short, the US took it upon itself to relegate the periphery, and the Developing World in toto, into the role of supplier of raw materials to Japan and Western Europe. In the process, American multinationals in energy and other mining activities counted themselves among the beneficiaries, as did many sectors of the US domestic economy. However, the Global Plan's architects saw much further than the narrow interests of any company. Their audacious policies to promote capital accumulation in distant lands, over which they had no personal or political interest (in the narrow sense), can only be explained if we take on board the weight of history under which they laboured.

Indeed, to understand the scale of the New Dealers’ ambition we must again take pause and look briefly for clues of what they were on about in their own, not too distant, past: in the Great Depression that formed their mindset. The Global Plan, we must not forget for a moment, was the work of individuals belonging to a damaged generation; a generation that had experienced poverty, a deep sense of loss, the anxieties engendered by the near collapse of capitalism, and a consequent war of inhuman proportions.

In addition, they were educated men (some of them with formal economics training) who understood in their bones what in this book we refer to as the economists’ Inherent Error; that deeply ingrained cause of serious theoretical failure affecting all economic modelling. They had vivid memories of how the great economists of the 1930s were fiddling with their models as the labour and capital markets were melting down. They knew that economics was

not a good source of advice on how to run capitalism. Some of them even understood that that was precisely the point of economics: to have nothing to say about really existing capitalism.

With these thoughts in their minds, and a determination in their hearts not to allow capitalism to slip and fall again under their watch, they calibrated and implemented their Global Plan with panache. Their thinking about what needed to be done was influenced by the writings of John Maynard Keynes, whose crucial message to them was not to trust markets to organise themselves in a manner that brings about prosperity and stability; and to distrust anyone who tells them that they have the measure of capitalism; that, through some economic model, however sophisticated, they can predict the great beast’s ways.

The break from Keynes was, nevertheless, inevitable. For whereas the Englishman had become convinced that global capitalism required a formal, cooperative system of recycling surpluses, the New Dealers both wanted and were obliged to tailor-make their Global Plan in the context of the Cold War imperatives and in clear pursuit of American hegemony (recall the White-Keynes class at Bretton Woods; see Box 11.1). Moreover, as Brinkley (1998) so vividly illustrates, the New Dealers lost, very early in the piece, their willingness seriously to confront corporate power.

To bring to fruition their joint task, of preventing another Great Depression and of constructing a new global order (with the United States at the helm and the American multinationals as effective agents of the state), the New Dealers knew that they would require a lot more than simplistic tinkering with monetary and fiscal policy.

What makes their story fascinating is the combination of their sophisticated, discursive Keynesianism, their audacious initiatives and the interaction of their economic planning with the demands of the Cold War. In this sense, the Global Plan comprised:

(a) not only the creation of the Deutschmark and Yen zones, by means of economic injections and political interference, to benefit Germany and Japan; but also

(b) the careful management of aggregate demand within the United States, always with a clear view to its effects on these two zones, in Europe and the Far East.

:Since (a) has already been discussed sufficiently, let us now turn to (b). Indeed, domestic demand was kept up at a healthy level (particularly during the 1960s) through three large public expenditure programmes, two of which were closely related to the Cold War:

• The Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) programme, which we discussed in Chapter 8 in the context of John von Neumann and the Scientists.

• The Korean and then, in the 1960s, the Vietnam War.

• President John Kennedy’s New Frontier and, more importantly, President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

The first two spending programmes substantially strengthened US corporations and kept them on side at a time when their own government was going out of its way to look after foreign capitalists. That strength played a role not only domestically (providing corporations with the sound basis they needed at home) but also internationally (where the said strength assisted the State Department and other US agencies in their endeavours).

The greatest benefits, of course, accrued to companies somehow connected to what President Dwight Eisenhower had disparagingly (even though a celebrated ex-army commander himself) labelled the Military-Industrial Complex (MIC). The latter, and its special treatment, contributed heftily to the development of the Aeronautic-Computer-Electronics complex (ACE); an economic powerhouse largely divorced from the rest of the US economy but central to its continuing power (see Markusen and Yudken, 1992; Me! man, 1997).

Despite the sizeable positive impact of the Global Plan on the domestic American economy and particularly on maintaining a high level of aggregate demand within the United States' it was an uneven impact and also an impact that may well have been a mere (however hugely desirable) by-product of Washington’s main policy; namely, of the policy to prioritise energy and input supplies (at favourable prices) for the reconstruction and development of Europe and Japan.

That it was uneven is evidenced from the fact that segments of the economy not linked to the MIC and the ACE (see the previous paragraph), never recovered in step with either Germany and Japan or with the rest of the US economy.7 That it was «of Washington’s main aim to bolster American companies (though it was certainly one of its aims) can be gleaned from the ruthlessness with which the United States government introduced, whenever it saw fit, harsh regulations which ultimately discriminated against American multinationals in pursuit of its top priority; the augmentation of the Deutschmark and the Yen zones via the reinforcement of German and Japanese industry (see Forsberg, 2000).

The unevenness with which prosperity was distributed within the United States, at a time of rising aspirations (not all of them income related), caused significant social tensions. These tensions, and their gradual dissolution, were the target of the Great Society spending programmes of the 1960s. At first President Kennedy and then his successor, Lyndon Johnson, pushed hard for a series of domestic spending programmes that would address the fact that the Global Plan's domestic benefits were so unfairly spread as to undermine social cohesion in important urban centres and regions. To prevent these centrifugal forces from damaging the Global Plan, social welfare programmes acquired an inertia of their own. Box 11.5 gives a flavour.

Box 11.5 The Great Society A New Deal in the age of the Global Plan

From 1955 until the election of President Kennedy in 1960, economic growth tailed off in the United States, a petering out that affected mostly the poor and the marginal. After eight years of Republican rule, Kennedy was elected on a New Deal-alluding platform. His New Frontier manifesto promised to revive the spirit of the New Deal by spending on education, health, urban renewal, transportation, the arts, environmental protection, public broadcasting, research in the humanities, etc. After Kennedy's assassination, President Johnson, especially after his 1964 landslide electoral victory, incorporated many of the, largely unenacted, New Frontier policies into his much more ambitious Great Society proclamation. While Johnson pursued the Vietnam War abroad with increasingly reckless vigour, domestically he attempted to stamp his authority through the Great Society, a programme that greatly inspired progressives when it put centrestage the goal of eliminating not only poverty for the white working class but also racism.

The Great Society will be remembered for its effective dismantling of American apartheid, especially in the southern states. Between 1964 and 1966, four pieces j

of legislation saw to this major transformation of American society. However, the Great Society had a strong Keynesian element that came to the fore as Johnson’s j ‘unconditional war on poverty’, in its first three years, 1964 to 1966, one billion dollars | were spent annually on various programmes to boost educational opportunities and | to introduce health cover for the elderly and various vulnerable groups.

I The social impact of the Great Society’s public expenditure was mostly felt in the I form of poverty reduction. When it began, more than 22 per cent of Americans lived i below the official poverty line. By the end of the programme, that had fallen to just below [ 13 per cent. Even more significantly, the respective percentages for Black Americans I were 55 per cent (in 1960) and 27 per cent (in 1968). While such improvements cannot be explained solely as the effect of Great Society funding, the latter played a major role in relieving some of the social tensions during an era of generalised growth.1

|

Note

1 For more on the Great Society see Kaplan and Cuciti (1986) and Jordan and Rostow (1986).

In retrospect, the results of the Global Plan's implementation were impressive. Not only did the end of the Second World War not plunge the United States, and the rest of the West, into a fresh recession, as it was feared that the winding down of war spending would do, but instead the world experienced a period of legendary growth. Figure 11.1 offers a glimpse of these golden years. The developed nations, victors and losers of the preceding war alike, grew and grew and grew.

The Europeans and Japan, starting from a much lower level than the United States, grew faster and made up for lost ground while, at the same time, the United States continued along a path of healthy growth. However, this was not a simple case of a spontaneously growing world economy. There was a Global Plan behind it, one that involved a large-scale, and impressively ambitious, effort to overcome and to supplant the multiple, conflicting imperialisms that characterised the world political economy until the Second World War.

Figure 11.1 Real GDP per capita during the period of the Global Plan.

USA

Germany

Japan

Britain

France

Table I LI Percentage increase/decrease in a country’s share of world GDP

USA Germany Japan Britain France

1950-72 -19.3% +18% +156.7% -35.4% +4,9%

The essence of that effort is captured nicely in Table 11.1 : American hegemony was purchased as the price of intentionally bolstering demand and capital accumulation in Japan and Germany, To maintain American prosperity and growth, Washington purposefully dished out part of the global ‘pie’ to its protégés, Germany (an increase in its share of world income of 18 per cent) and even more so Japan (a stupendous 156.7 per cent).

To conclude this section, the preceding thoughts lead to a reassessment of post-war US dominance from the perspective of the United States’ balance of payments in relation to the rest of the world. While seemingly in competition with the United States, the economies of Germany and Japan were aided and propped up by their former conqueror. Was this a form of internationalist altruism at work? The more we consider the long-term interests of American accumulation, in the light of the 1930s experience, the less credible the altruistic explanation seems.

At the heart of the New Dealers’ thinking, from 1945 onwards, was an intense anxiety regarding the inherent instability of a single-currency, single-zone global system. Indeed, nothing concentrated their minds like the memory of 1929 and the ensuing crisis. If a crisis of similar severity were to strike while global capitalism had a single leg to stand on (the dollar), and in view of the significant growth rates of the Soviet Union (an economy not susceptible to contagion from capitalist crises), the future seemed bleak. Thus, these same minds sought a safer future for capitalism in the formation of an interdependent network comprising three industrial-monetary zones, in which the dollar-zone would be predominant (reflecting the centrality of American finance, and its military ‘defence of the realm’ in the sphere of securing inputs from the Developing World). To them, this Global Plan was the optimal mechanism design for the rest of the twentieth century and beyond.

In this sense, and if our analysis is correct, the notion that European integration sprang out of a European urge to create some bulwark against American dominance appears to be nothing more than the European Union’s ‘creation myth’. Equally, the idea that the Japanese ; economy grew inexorably against the interests of the United States does not survive serious scrutiny. However strange this may seem (especially to readers whose more recent memories of the United States are the introverted years of the 2000-08 period), behind the process of European integration and of Japanese export-oriented industrialisation lies a prolonged and sustained effort by Washington policymakers to plan and nurture it, despite the detrimental effects on America’s balance of trade that the rise of Europe and Japan entailed.

The simple lesson that the Global Plan can teach us today is that world capitalism’s finest hour came when the policymakers of the strongest political union on the planet decided to play an hegemonic role; a role that involved not only the exercise of military and political might but also a massive redistribution of surpluses across the globe that the market mechanism is utterly incapable of effecting.

11.4 The Global Plan’s unravelling

The Global Plan's path was not laid with roses. From its inception, a series of developments conspired to undermine it (with Chairman Mao’s triumph delivering the first and most

serious blow). But even when parts of it were overturned by the vagaries of reality, such failures prompted creative responses which maintained the Plan’s integrity, often as a result of unintended consequences.

The Vietnam War is a good case in point. Though it is a gross understatement to suggest that its persecution did not go according to the original plan, the silver lining is visible to anyone who has ever visited South-East Asia. Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore crew fast and in a manner that frustrated the pessimism of those who predicted that underdeveloped nations would find it hard to embark upon the road of capital accumulation necessary to drive them out of abject poverty. In the process, they provided Japan with valuable trade and investment opportunities, therefore shoring up the Plan’s eastern flank.

Just as Japan’s economy began to grow on the back of US military spending during the Korean war, the tigers of South-East Asia were the offspring of enormous investment, paid for from the US military budget, during the lengthy, tragic conflict in Indochina (see Hart-Landsberg, 1998). Ho Chi Minh’s stubborn refusal to lose the war, and Lyndon Johnson’s almost manic commitment to do all it takes to win it, were crucial in creating a new capitalist region in the Far East, one that would eventually play a major role in the more recent rise of the Chinese behemoth. Nonetheless, these developments proved a bridge-too-far for the Global Plan. The escalation of the financial costs of that war that were to be a key fac tor in its demise.

As the costs of Johnson’s Great Society and of the Vietnam War began to mount, the Fed was forced to take on mountains of US government debt. In effect, it was printing the necessary dollars to finance the two interrelated ‘projects’. Towards the end of the 1960s, many governments began to worry that their own position, which was interlocked with the dollar in the context of the Bretton Woods system, was being undermined. By early 1971, liabilities in dollars exceeded 70 billion when the US government possessed only $12 billion of gold with which to back them up.

The increasing quantity of dollars was flooding world markets, giving rise to inflationary pressures in places like France and Britain, European governments were thus forced to increase the quantity of their own currencies in order to keep their exchange rate with the dollar constant, as stipulated by the Bretton Woods system. This is the basis for the European charge against the United States that, by pursuing the Vietnam War, it was exporting inflation to the rest of the world. In addition, the Europeans and the Japanese feared that as the quantity of dollars was rising, and with the US stock of gold constant, a run on the dollar might force the United States to drop its commitment to swapping an ounce of gold for $35, in which case their stored dollars would devalue, eating into their national ‘savings’.

American dominance was, as explained earlier, built into the Bretton Woods system since it allowed the United States to be the only country that could print money at will in order to finance its global dominance. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who was at that time President de Gaulle’s finance minister, called this the exorbitant privilege of the Dollar. De Gaulle and other European allies (plus various governments of oil producing countries whose oil exports were denominated in dollars) accused the United States of building its imperial reach on borrowed money that undermined their countries’ prospects.

On 29 November 1967, the British government devalued the Pound sterling by 14 per cent, well outside the Bretton Woods 10 per cent limit, triggering a crisis and forcing the United States government to use up to 20 per cent of its entire gold reserves to defend the $35 dollars-to-one-ounce-of-gold peg. On 16 March 1968, representatives of the G7’s central banks met to hammer out a compromise. They came to a curious agreement which, on the one hand, retained the official peg of $35 an ounce while, on the other hand, left room for speculators to trade gold at market prices.

When Richard Nixon won the US Presidency in 1970, he appointed Paul Volcker as Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Monetary Affairs. His brief was to report to the National Security Council, headed by Henry Kissinger, who was to become a most influential Secretary of State in 1973. In May of 1971, the taskforce headed by Volcker at the Treasury presented Kissinger with a contingency plan which toyed with the idea of ‘suspension of gold convertibility’.It is now clear that, on both sides of the Atlantic, policymakers were jostling for position, anticipating a major change in the Global Plan.

In August 1971 the French government decided to make a very public statement of its annoyance at the United States’ policies: President Georges Pompidou ordered a destroyer to sail to New Jersey to redeem US dollars for gold held at Fort Knox, as was his right under Bretton Woods! A few days later, the British government issued a similar request, though without employing the Royal Navy, demanding gold equivalent to $3 billion held by the Bank of England.

President Nixon was absolutely livid. Four days later, on 15 August 1971, he announced the effective end of Bretton Woods: the dollar would no longer be convertible to gold. Thus, the Global Plan unravelled. Soon after, he dispatched John Connally, his Secretary of the Treasury, a no-nonsense Texan, to Europe. Connally’s account of what he said to the Europeans was mild and affable. He told reporters:

We told them that we were here as a nation that had given much of our resources and our material resources and otherwise to the World to the point where frankly we were now running a deficit and have been for twenty years and it had drained our reserves:and drained our resources to the point where we could no longer do it and frankly we were in trouble and we were coming to our friends to ask for help as they have so many times in the past come to us to ask for help when they were in trouble. That is in essence what we toid them.8

in reality this is not at all what he told the Europeans, either in form or in spirit. With the reporters out of range, Connally delivered a brutal message to European leaders; one whose shocking value is still remembered in Europe’s corridors of power. His real message was: it’s our currency but it’s your problem!

What Connally meant was that, as the Dollar was the reserve currency (see below) and the only tndy global means of exchange, the end of Bretton Woods was not America 's problem. The Global Plan was, of course, designed and implemented to be in the interest of the United States. But once the pressures on it, caused by Vietnam and internal US tensions that required an increase in domestic government spending, such that the system reached breaking point, the greatest loser would not be the United States itself but Europe and Japan; the two economic zones that had benefited enormously from the Global Plan.

It was not a message either the Europeans or Japan wanted to hear. Lacking an alternative to the dollar,9 they knew that their economies would hit a major bump as soon as the dollar started to devalue. Not only would their dollar assets lose value but, additionally, their exports would become dearer. The only alternative was for them to devalue their currencies too but that would then cause their energy costs to skyrocket (given that oil was denominated in dollars). In short, Japan and the Europeans found themselves between a rock and a hard place.

Towards the end of 1971, in December, Presidents Nixon and Pompidou met in the Azores. Pompidou, eating humble pie over his destroyer antic, pleaded with Nixon to reconstitute the Bretton Woods system, on the basis of fresh fixed exchange rates that would reflect the new ‘realities’. Nixon was unmoved. The Global Plan was dead and buried and a new beast was to fill in the vacuum in its wake.

11.5 Interregnum: The 1970s oil crises, stagflation and the rise of interest rates

Once the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton Woods system collapsed, all prices and rates broke loose. Gold was the first commodity to jump discretely from $35 to $38 per ounce, soon to $42 and then to float unbounded into the ether. By May 1973 it was trading at more than $90 and before the decade was out, in 1979, it had reached a fabulous $455 per ounce - a twelvefold increase in less than a decade.

Turning to a key rate for any capitalist economy, money (or nominal) interest rates rose too, from between 5 per cent and 6 per cent during the Global Plan’s final years to 6.44 per cent in 1973 and to 7.83 per cent the following year. By 1979, when President Carter’s administration began to attack inflation seriously, average interest rates topped 11 per cent. In the following year, June of 1981 to be precise, Paul Volcker (who was appointed by Carter as Chairman of the Fed in 1979) raised interest rates to a lofly 20 per cent, and then further up again to 21.5 per cent in 1981. While this brutal form of monetary policy did tame inflation (pushing it down from 13.5 per cent in 1981 to 3.2 per cent two years later), its harmful effects on employment and capital accumulation were profound, both domestically and internationally.

And yet, despite the scorched earth aspects of the high interest rate policies of Volcker’s Fed, the mission was accomplished: the United States’ early 1970s problems with competitiveness and its balance of payments had disappeared. Capital flows to New York, due both to the high interest rates and the fast declining inflation rate, were allowing the US administration to emancipate itself from the deep red ink splattered all over the country’s international trade balance sheet.

The United States could now run an increasing trade deficit with impunity while the new Reagan administration could also finance its tremendously expanded defence budget. The latter proved essential in curbing unemployment which, between 1979 and 1983, was getting out of control. These two deficits (the US trade deficit and the US government’s budget deficit) changed the post-1970s world. In our parlance, they constituted a Global Minotaur whose imprint we still see around us everywhere we look, a creature whose demise in 2008 promises to shape another, the third, phase of the post-war reality.

Turning back to the 1970s again, and the predicament of the Europeans, of the Japanese and of the oil-producing countries once the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton Woods system had been and gone, at the centre of their crisis (recall Connally’s ‘It is our dollar but it is your crisis’!) was the devaluation of the dollar. Within two years of Nixon’s August 1971 bold move, it had lost 30 per cent of its value against the Deutschmark and 20 per cent against the yen and the franc. Oil producers suddenly found that their black gold, when denominated in yellow gold, was worth a fraction of what it used to be. Members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which regulated the price of oil through agreed cutbacks on aggregate oil output, were soon clamouring for coordinated action (i.e. reductions in production) to boost the black liquid’s value.

At the time of Nixon’s announcement, the price of oil was less than $3 a barrel. Soon after, concerted effort was put into bringing about a hike. In 1973, with the Yom Kippur war between Israel and its Arab neighbours apace, the price jumped to between $8 and $9, thereafter hovering in the $12 to $15 range until 1979. In 1979 a new upward surge began that saw oil trade above $30 well into the 1980s.10 It was not just the price of oil that scaled unprecedented heights. All primary commodities shot up in price simultaneously: bauxite (165 per cent); lead (170 per cent); silver (1065 per cent); and tin (220 per cent) are just a few examples. In short, the termination of the Global Plan signalled a mighty rise in the costs of production across the world.

Did Nixon, Kissinger and Connally miscalculate? Had they brought about a major catastrophe upon the United States and the capitalist world at large by allowing their anger towards the Europeans to create the circumstances of an economic implosion? Or was"all this part of a plan of sorts? As alluded to above, there was no miscalculation. Although not all of the repercussions had been anticipated, and indeed some proved exceedingly costlv the general drift was as planned.

The conventional wisdom of what happened in the early 1970s is that, against the will of the United States, OPEC countries (because the dollar began to slide, and was no longer exchangeable for gold at a fixed rate) tried to recoup the real (or gold) price of their oil by restricting shipments and production, thus pushing oil dollar prices sky high. Taking advantage of the conflict in the Middle East, they bound the Arab and Muslim nations together, imposed an embargo on the United States and thus managed to boost oil prices and, naturally, their collective revenues. With the cost of energy scaling such heights, inflation spread to the rest of the world, nominal interest rates followed in sympathy and the developed economies were thus brought to their feet.

If all this were true, one would have expected the United States government to have regretted President Nixon’s 1971 break from Bretton Woods and to have vehemently opposed anyone within OPEC trying to bring about a binding agreement to curtail oil production. But no such regrets were ever expressed. Moreover, a country that had no compunction in bringing down Mohammad Mossadegh’s democratically elected government in Iran in 1953 (to prevent the nationalisation of that country’s oil wells) and staging one coup d'état after the other for the purposes of safeguarding its interests worldwide (from Greece and Indonesia in 1967, to Chile in 1973 and almost in every other Latin American country during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s), did not raise a finger to effect political or .‘other’ means that would have so easily prevented the OPEC oil price hikes.

So, why didn’t they do something to stop the oil price rises? Why not undermine- the regimes pushing for them? The simple reason is that the Nixon administration neither regretted the end of Bretton Woods nor cared to prevent OPEC from executing oil price rises. Why? Because these hikes were utterly consistent with the administration’s very own plans for a substantial increase in the prices of energy and primary commodities! (see Box 11.7)

Now, this is a large claim, in need of substantiation. Thankfully, our claim comes, so to speak, from the horse’s mouth. In his 1982 memoirs, Years of Upheaval, Henry Kissinger writes: ‘Never before in history has a group of relatively weak nations been able, to impose with so little protest such a dramatic change in the way of life of the overwhelming majority of the rest of mankind’ (1982: 887). And why did Kissinger, a man of incredible power in the Nixon administration, not protest? It is now well accepted (see Oppenheim, 1976/7 and Box 11.6 below) that the reason why there was so little US resistance to OPEC’s price increases was that US policymakers, including Kissinger, were quite happy to see oil prices quadruple. In fact, they worked diligently to push them up!

The obvious question is: why would they want to do that? Why, oh why, would the Nixon administration embark upon a strategic plan whose effect would be to increase production costs worldwide, risk hyperinflation, produce mass unemployment for the first time since the late 1930s and, generally, destabilise capitalism? For this is precisely what happened in the 1970s: for the first time in capitalist history, we witnessed a combination of inflation and

j Box 11.6 Vietnam War: Counting the costs | The economic cost

j

The direct accounting cost of the Vietnam War for the United States government was a staggering $113 billion. New Deal Keynesian economist Robert Eisner (Professor at Northwestern University and a former President of the American Economic Association), computed the total economic cost of the Vietnam War for the United States’ economy to have been closer to $220 billion. Moreover, he suggested that real US corporate profits declined by 17 per cent. At the same time, during the period 1965 -70, the war-induced increases in average prices forced the real average income of American blue-collar workers to fall by about 2 per cent. ‘This loss in income’, wrote Eisner, ‘must be a major factor in working-class malaise and tension’. In this context, President Johnson’s Great Society (see Box 11.5) was also (though not exclusively) a domestic policy to counter the increasing tensions due to the Vietnam War, which Johnson pursued with such fervour.

The human cost1

South-East Asia

• 1,921,000 Vietnamese died

• 200,000 Cambodians died (1969-75)

• 100,000 Laotians died (1964-73)

• 3,200,000 were wounded (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia)

• 14,305,000 were refugees (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) by the end of the war

• in general, approximately one out of 30 IndoChinese was killed between 1964 and 1973; one in 12 wounded; and one in five made a refugee

USA

• 2,500,000 soldiers served in the war

• 58,135 soldiers died

• 303.616 were wounded

• 33,000 were paralysed as a result of injuries

• 111,000 veterans died from ‘war-induced’ conditions since returning home (including at least 60,000 suicides)

• 35,000 US civilians were killed in Vietnam (non-combat deaths)

• 2,500 were missing in action

Note

1 The figures here come from the US Department of Defence and the United Nations. Eisner’s estimates were reported in Time magazine’s article “Business: The Hidden Costs of the Viet Nam War”, Monday, July 13, 1970.

unemployment at once;11 a condition that required a new label: stagflation - a moment in history when the two dragons feared most by policymakers visited every capitalist centre simultaneously. Surely, it is preposterous to believe that it was the United States government that issued the dragons’ invitations!

Box 11.7 An odd ‘crisis’

' Who pushed oil prices up ’? — 'We did’!

With average consumer and commodity prices rising across the industrial world, the dollar price of oil stagnant, and the dollar devaluing relative to gold, OPEC began to make noises from as early as December 1970 about impending action to boost the price of oil. The Western oil companies, the so-called Seven Sisters, immediately demanded bilateral monopoly negotiations with OPEC. Remarkably, it was the US government that scuttled the negotiations, ensuring that the oil companies did not get a chance to negotiate with OPEC on a one-to-one (or bilateral monopoly) basis; a negotiation in which they would exercise a great deal more bargaining power than they would in piecemeal discussions. Oppenheim (1976/77) writes

‘...a split was announced in the talks in Tehran by a special US envoy, then Under-Secretary of State John Irwin, accompanied there by James Akins, a key State Department man on oil...,[T]he real lesson of the split in negotiations with OPEC was that higher prices were not terribly worrisome to representatives of the State Department... the whole subject of what the negotiations were about began to focus not on holding the price line but on ensuring security of supply’.

Oppenheim also quotes extensively from an article by an advisor to the Libyan government on how the United States successfully undercut Europe’s attempts to secure lower oil prices. In particular, US representatives refused to contribute to a series of initiatives proposed in various open and secret groups meeting in Paris at the OECD, the purpose of which was to work out oil-sharing arrangements in the event of an embargo. Oppenheim continues: ‘In fact, the prediction, and advocacy, of higher oil prices became a common feature of statements from the Nixon administration’.

In 1972, the same Mr Akins that undermined the oil companies’ bargaining position in Tehran two years previously told an audience at the 8th Petroleum Congress of the League of Arab States that ‘. oil prices could be expected to go up sharply due to lack of short-term alternatives to Arab oil,’ a turn of phrase that was widely interpreted as an American green light on oil price increases. Akins’ career continued to revolve around oil, rising to US Ambassador to Saudi Arabia. In his confirmation statement to Congress, he stated clearly that the United States was never really opposed to oil price increases.

It is important to note that all of the above transpired well before the Yom Kippur war and the oil embargo that ensued (during which the Arab countries restricted oil sales to Israel’s Western allies). During that Arab-Israeli war and the oil (i.e. at a time one would have expected the hawkish Dr Kissinger to unleash the powers of hell against the Arab countries that were simultaneously attacking Israel and holding the United States to ransom), Kissinger continued secretly to channel foreign aid and investments to Saudi Arabia. Akins himself later testified that, in 1975, Kissinger was cajoling the Shah of Iran to let oil prices rise further.

By 1974, US officials lower down the Washington pecking order of the administration were learning, often at great personal cost, that higher oil prices, rather than a hindrance, had become a strategy. For example, the Chief of the Federal Energy Administration, John Sawhill, found this out the hard way when his efforts to reduce oil prices were blocked by persons of greater rank and authority within the Nixon administration: before he knew it, his persistence was met with a summary dismissal.

Moreover, such a choice seems to fly in the face of at least two decades of American policy in the context of the Global Plan; history’s most impressive attempt to regulate capitalism on the basis of creating a stable environment in which all major capitalist centres prosper, with the United States maintaining the leading position. Nothing short of collective madness would explain how Washington’s global stability builders would choose to throw such a sizeable spanner in global capitalism’s works.

Are we, therefore, being disingenuous to claim that the hike in oil prices, which opened up Pandora’s box and turned the 1970s into a decade of turmoil and instability, was planned? Not in the slightest, we submit. Our position on this delicate matter is that, naturally, no one chose stagflation, high interest rates, expensive raw materials, etc., as such. Rather, Washington’s policymakers made a different choice under duress: one between:

(a) serious cutbacks in government spending and in the living standards of the American middle class and its elites (a decline that would have been inevitable if the United States were to cut its trade deficit); and

(b) a strategy that would allow the United States to liberate itself from the constraint of its twin deficits (the trade and the government budget deficits).

To explain this choice better, we note that, once the Global Plan began to unravel, the United States was facing a serious problem to which Treasury Secretary Connally alluded when he addressed the Europeans in public in September 1971:

[A]s a nation that had given much of our resources and our material resources and otherwise to the World to the point where frankly we [are],.. now running a deficit and have been for twenty years and it had drained our reserves and drained our resources to the point where we could no longer do it and frankly we were in trouble.

Connally was telling the truth, not the whole truth but the truth nonetheless: the United States’ balance of payments deficit had become unsustainable, reflecting the extent to which the Vietnam War was confounding the US military’s best efforts. Additionally, American industry had lost its edge. In comparison to the burgeoning productivity of German and Japanese industries, American manufacturers were falling behind, and were doing so unprotected by tariffs from the German and Japanese goods that the American government was intentionally letting into the land, as part of its plan to patronise the two former enemies’ industries. With profitability dipping quickly, a large trade deficit developing, and an ever-increasing public debt, the United States had to change course or forfeit its hegemony there and then.

The choice it faced was, therefore, simple, As we suggested above, it had to choose between a major reduction in the American middle and elite classes’ living standards and a strategy that would, effectively, free the United States from its balance of trade and government deficit constraints. ‘How could the latter be an option?’, the reader will rightly ask. Is it not a little like inventing perpetual motion or squaring the circle? Surely it is not possible to liberate a country from its two major shackles: the budget and the balance of trade constraints. Only it is, when the country in question issues the world’s sole reserve currency; the money that everyone uses to pay for energy and other major commodities; the currency one turns to when the dark clouds of crisis of recession gather.

Having ruled out as unacceptable the first option, the reduction in US government spending and a general fall in imports and associated living standards for well-to-do Americans, the Nixon administration embarked on a quest for an ingenious way to continue with hieh trade and budget deficits by making other people, foreigners, pay for them. It will be our contention in this chapter’s remaining pages that the Nixon administration, and every administration that followed it since, opted for this exceptionally alluring option.

The aim of the new strategy was to redress the balance of payments situation between the three major zones on which the Global Plan had staked its integrity: the United States, Europe and Japan. Looking back to Table 11.1, this means a shift of the global surplus back to the United States, and away from Germany, Japan and the oil-producing countries. Two were prerequisites of that simple end:

(i) to improve the competitiveness of US firms in relation to their German and Japanese competitors; and

(ii) to attract large capital flows into the United States that would cancel out the US balance of trade deficit and pay for the US government’s chronic deficit.

Prerequisite (i) could be achieved in one of two ways: either by boosting productivity in the United States or by boosting the relative unit costs of the competition. The US administration decided to aim for both, for good measure. Labour costs were squeezed with enthusiasm and, at the same time, oil prices were ‘encouraged’ to rise; precisely as we argued above. The basic assumption here was that, in the estimation of the US authorities, both Japan and Western Europe would find it much harder than the United States to deal with a significant increase in oil prices. How right they were!

Prerequisite (ii) was closely linked to (i). The drop in US labour costs not only boosted the competitiveness of American companies, but also acted as a magnet for foreign capital that was searching for profitable ventures. Similarly, the rise of oil prices led to mountainous rents piling up in bank accounts from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia. It was only a small step for their owners to wire them to their bank accounts in Wall Street, thus contributing to the sought after (by US administrators) capital flight into the United States.12 And if oil-sourced monies were to crave a trip to Wall Street, that would also apply to the surpluses accumulating in the bank accounts of the manufacturers, Japanese and German, who owed their very existence to the now sadly deceased Global Planl The vast increases in US interest rates of the later 1970s did no harm in this regard either.

In short, a new phase was beginning. Gone were the days when the United States would be financing (either directly or through war financing or totally indirectly, by the exercise of political power) Germany and Japan, hoping to create in those countries substantial markets for American high technology, military and other goods and adding, in the process, important shock absorbers (the Deutschmark and the Yen) to the international monetary system. The new era would be different. America would be importing like there was no tomorrow, and its government would splurge out unhindered by the fear of increasing deficits, with foreign investors sending billions of dollars every day to Wall Street, quite voluntarily and for reasons completely related to their bottom line, to make up the difference and plug the United States’ twin deficits.