American officials may not have been ‘shaking in their boots’ when reading the Europeans’ farcical policy documents, but they were worried nevertheless. As befits a true hegemon, the United States produced a no-nonsense mindset among its high and mighty that empowered them to do what the Europeans had no stomach for: to look the Minotaur in the eye and not blink. Paul Volcker, our acquaintance from Chapter 11 (where he featured initially as a young Undersecretary of the Treasury, suggesting to his superiors the euthanasia of Bretton Woods and then re-appeared again in 1979 as the Fed Chairman who ruthlessly increased interest rates and did his utmost to serve the Minotaur's rise), had this to say in 2005:

What holds [the US economic success story] all together is a massive and growing flow of capital from abroad, running to more than $2 billion every working day, and growing. There is no sense of strain. As a nation we don’t consciously borrow or beg. We aren’t even offering attractive interest rates, nor do we have to offer our creditors protection against the risk of a declining dollar... It’s all quite comfortable for us. We fill our shops and our garages with goods from abroad, and the competition has been a powerful restraint on our internal prices. It’s surely helped keep interest rates exceptionally low despite our vanishing savings and rapid growth. And it’s comfortable for our trading: partners and for those supplying the capital. Some, such as China, depend heavily on our expanding domestic markets. And for the most part, the central banks of the emerging world have been willing to hold more and more dollars, which are, after all, the closest thing the world has to a truly international currency... The difficulty is that this seemingly comfortable pattern can’t go on indefinitely. I don’t know of any country that: has managed to consume and invest 6% more than it produces for long. The United^ States is absorbing about 80% of the net flow of international capital. And at some point, both central banks and private institutions will have their fill of dollars.s

We could not (and would not have tried to) put it better ourselves. If the Global Minotaur requires an introduction, the above description by Paul Volcker will do nicely. As further proof that US powerbrokers were completely aware and wary of the Minotaur's massive: footprint on the planet’s economy, here is what Stephen Roach, the Chief Economist of investment bank Morgan Stanley, had to say in 2002 in response to fears that a bubble was building up within the US financial markets:

This saga is not about the bubble. It is about the unwinding of a more profound asymmetry in the global economy, the rebalancing of a US-centric world... History tells us that such asymmetries are not sustainable... Can a savings-short US economy continue to finance an ever-widening expansion of its military superiority? My answer is a resounding no. The confluence of history, geopolitics, and economics leaves me more convinced than ever that a US-centric world is on an unsustainable path.9

Volcker and Roach were in agreement. The causes of the post-1980 take off of the Anglo-Celtic economies has nothing to do with entrepreneurship, labour market flexibility and all the nonsense that Europeans mistook for the causes of their own economies’ stagnation. There was a Minotaur in the room whose brute power was helping the United States expand its multifarious hegemony. However, the asymmetries that were created and amplified in its wake were unsustainable. Volcker and Roach feared that when that ‘unsustainability'

came to the fore, as it would, the world was in for a major shock with unmanageable

repercussions.

Note the profound difference between this viewpoint and the mundane talk of labour market reforms or of the fear of bubbles. While not saying so explicitly, both Volcker (the seasoned policymaker) and Roach (the Wall Street analyst) were alluding to some major changes in the foundations of capitalism that have given rise to deep asymmetries transcending the realm of labour market policy or the inevitable build up of bubbles in the financial markets. The two men were on to something bigger and more profound.

In Chapter 7 we began our account of the Crash of1929 with a section on a new phase of capitalism that was sweeping all in its path during the three decades that preceded the Crash. Using Edison and Ford as paradigmatic figures of that transformation, we told the story of how the rise of corporations changed capitalism’s face; of how technological innovations led to a higher concentration of increasingly massive investment in the hands of a small number of industry moguls and of how that concentration went hand in hand with an expanding role for the stock market and of the financial institutions connected to it.

Our point there was that it is impossible to understand capitalism’s worst moment (the Crash of 1929) without first acquainting ourselves with (a) the prior emergence of a new phase of capitalism (referred to, usually, as monopoly capitalism, oligopoly capitalism or corporate capitalism); and (b) the deeper and broader uncertainty brought about by finan-dalisation. Precisely the same applies here today, in our inquiry into the Crash of2008. Yet again, we shall be arguing, the Crash was preceded by the unfolding of a new capitalist phase and the onslaught of a new financialisation phase. We call the confluence of these two new phases Double-W capitalism. To give a hint of our argument, we start by giving away the origin of the two W’s: Wal-Mart is one and Wall Street is the other.

The Wal-Mart Extractive Model

Wal-Mart is one of the largest conglomerates in the world. With annual earnings in excess of S320 billion, it is second only to oil giant Exxon-Mobile. The reason it is singled out here is because, we believe, Wal-Mart symbolises a brand new phase of capitalist accumulation, one that is central to recent developments worldwide.

Unlike the first conglomerates that evolved on the back of impressive inventions and technological innovations in the 1900s, Wal-Mart and its ilk built empires based on next to no technological innovation, except a long string of ‘innovations’ involving ingenious methods of squeezing their suppliers’ prices and generally hacking into the rewards of the labourers involved at all stages of the production and distribution of its wares. Wal-Mart’s significance revolves on a simple point: in the era of the Global Minotaur it traded on the American working class’ frustration from having lost the American Dream of ever-increasing living standards (recall Table 11.4), and its related need for lower prices.

Unlike other corporations that focused on building a particular brand within a previously defined sector (e.g. Coca Cola or Marlboro), or companies that created a wholly new sector by means of some invention (e.g. Edison with the light bulb, Microsoft with its Windows software, Sony with the Walkman, or Apple with the iPod/iPhone), Wal-Mart did something no one had ever thought of before. It built a new Ideology of Cheapness into something of a brand that was meant to appeal at a time the American working class was frustrated by diminishing living standards.

Fishman (2006) offers an anatomy of the new industrial model that Wal-Mart introduced during our Minotaur’s ascent. Take his example of Vlasic pickles, a well-known brand

in the United States. Wal-Mart’s ‘innovation’ was to sell these pickles in one gallon (3.9 litre) jars for $2.97. Fishman’s point is that this was not a shrewd retailer’s response to market demand. No one in their right mind wanted to buy almost four litres of pickles Few family fridges had the necessaiy room for such an item. The selling point was the idea of a huge quantity at an ultra low price. Wal-Mart’s buyers, in this sense, were not buying pickles as such. They were buying into the symbolic value of cheapness; of having managed to put in their homes a large jar of pickles that Wal-Mart’s monopoly power had forced producers to make available at a cut-throat price.

Most of the pickles themselves ended up in the bin, as very few families managed to consume them before they went off (since few found room for them in their fridges). As Korkotsides (2007) so astutely explains in his book Consumer Capitalism, the working class, unable to do something about the increasing rate of extraction of its own labour bv capital, at least took some pleasure in ‘buying’, from companies like Wal-Mart, the labour extracted from other workers. The jar of pickles in the fridge, in this reading, was no more than a small victoiy at a time of wholesale defeat.

: Wal-Mart’s strategy reverberated around the world. Take the case of Chilean Atlantic salmon that Wal-Mart sold, in 2006, for $4.84 a Pound. As Fishman (2006) explains, salmon is not native to Chile and it was only farmed there en masse because of Wal-Mart’s mass orders which ushered in ‘an industrial revolution that has turned thousands of Chileans from subsistence farmers and fishermen into hourly paid salmon processing plant workers'. Lanchester (2006) adds that ‘the salmon live in huge underwater pens, and leave a “toxic sludge” of excrement and uneaten food on the ocean bed’. Similarly with Brazilian beef that Wal-Mart advertises at prices that cannot possibly be consistent with animal husbandly based on half decent practices. Lanchester’s (2006) astute comment sums the situation up nicely: ‘The feeling [these prices] give is a little like the one that washes over you when you see flights advertised for 99p: something just isn’t right’.

Clues as to what is wrong are not hard to come by. Take Wal-Marfs domestic employees: It does not have any! At least not according to Wal-Mart which describes its employees as ‘associates’. What this means is that the company does not consider itself to be bound to its workforce by means of the problematic labour contract (discussed in Chapters 4 and 5) but, instead, by individual contracts like those struck between two sellers. Wal-Mart effectively declares itself liberated from the trouble with humans (recall Chapter 4). This is no more: than Orwellian language by which to explain its blanket ban on any trade union activity on its premises. The result is that Wal-Mart’s ‘associates’ work for less than $ 10 per hour,11 are habitually forced to work overtime with no additional pay and are often locked up inside the warehouses while working overnight. Lanchester (2006) reports that these practices have resulted in lawsuits in 31 states.12

The situation in the workshops and fields of the Developing World, where goods are grown or produced on behalf of Wal-Mart, is, as one can imagine, bordering on the criminal. Defenders of the type of globalisation imposed upon an unsuspecting world by Wal-Mart and the Minotaur will argue that growth has been strong for two decades internationally, a trend that seems to continue. Surely, this is good for the poor. But what this misses is the distributive effect of Wal-Mart-type practices on the poor. The United Nations report on global poverty tells us that in and around 1980, for every $100 of world growth, the poorest 20 per cent received $2.20. Twenty-one years later, in 2001, an additional $100 of world growth translated in a measly extra 60 cents for the poorest 20 per cent. And when one takes into account that disproportional rise in prices for basic commodities as well as the diminution in public services following the IMF’s structural adjustment programmes (following the

peveloping World Debt Crisis of the 1980s), there appears to be very little cause for celebration on behalf of our poverty-challenged fellow humans.

In Robert Greenwald’s 2005 shocking documentary Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price a woman working in a Chinese toy factory asks ‘Do you know why the toys you buy are so cheap?’ and then proceeds breathlessly to answer her own question: ‘It’s because we work all day, every day and every night’. Fishman (2006) adds to this the account of another factory worker who works in a clothes factory that supplies cheap trousers to Wal-Mart. Her labour contract stipulates that she must complete 120 pairs of trousers per hour, work 14 hours daily and get 10 days holiday annually. As for the incentive mechanism that keeps her productivity so high, in her own words, ‘if you make any mistakes or fall behind your goal, they beat you’.

Box 12.3 Wal-Mart: A corporation after the Minotaur's heart

Wal-Mart was the creation of Sam Walton who ‘discovered’ that low prices can be lucrative. This sounds nothing like an epiphany: any first-year economics student will tell you that, if demand for a set of goods is elastic, the best strategy to maximise revenues is to charge low prices. However, Walton’s ‘concept’ went far beyond that: first, he worked hard to ensure that his low prices kept falling from year to year (or at least seemed to do so). Thus, Wal-Mart did not just concentrate on low-elasticity products, where a low price maximised profits, but, and this is crucial, cultivated in the consciousness of its customers an ideological expectation of f alling prices. Secondly Walton set out to expand everywhere. Having started his first outlet in Arkansas in 1962, by 1970 the number of outlets rose to 32, by 1976 to 125 and by 1980 to 276 outlets netting the company annual revenues exceeding $1.2 billion. In

2007 Wal-Mart employed more than two million workers, becoming the largest employer in 35 states and expanded to Britain, Mexico and Canada. Third, Wal-Mart embarked upon a major drive to commodify labour and, just as it did with every other commodity it touched, to cheapen it.

The immediate macroeconomic effect of the Wal-Mart ‘business model’ (that was adopted by many other companies, e.g. Starbucks) was, quite obviously, anti-inflationary. This was essential for the Global Minotaur's continuing rude health since the flow of foreign capital to the United States was, partly, predicated upon US inflation trailing that of other, competing, capitalist centres. In Wal-Mart’s defence one may argue that it was simply responding to the facts. As the Minotaur was gathering strength, American workers (recall, once again, Table 11.4) felt their diminishing purchasing power in their bones. Wal-Mart simply responded to this reality by providing them with basic products at prices reflecting their diminishing capacity to pay. Was this not a decent helping hand that helped American families in need from slipping into poverty?

This is the conventional wisdom, not least among the American working class itself. However, there is now plenty of evidence that the truth begs to differ; that Wal-Mart’s overall effect has been quite the opposite; that wherever Wal-Mart expanded, poverty rates rose. To be more precise, the 1990s was a period of rapid growth in the United States, courtesy of the Minotaur and its astonishing capacity to

2 Kenneth Stone, an economics professor at Iowa State University, has published a number of ! reports showing that, while Wal-Mart employs a large number of workers in its gargantuan I warehouses, the overall effect of its operations on employment is decisively negative. Small j town stores close down when Wal-Mart comes to town and, more poignantly, total sales and total employment fall even though Wal-Mart’s sales and employment levels seem impressive I enough. See Stone (1988), Stone (1997) and Stone, Artz and Myles (2000). j

Summing up, Wal-Mart represents more than monopoly or oligopoly capitalist industry. It represents a new guise of monopoly capitalism which evolved in response to the circumstances brought on by the Global Minotaur. The Wal-Mart extractive business model reified cheapness and profited from amplifying the feedback between failing prices and falling purchasing power on the part of the American working class. It imported the Developing World into American towns and regions and exported jobs to the Developing World (through outsourcing), causing the depletion of both the ‘human stock’ and the natural environment everywhere it went. Wherever we look, even in the most technologically advanced US corporations (e.g. Apple), we cannot fail to recognise the influence of the Wal-Mart model. The Minotaur and Wal-Mart rose in prominence at about the same time. It was not a coincidence.

The Wall Street money creation model

The previous chapter concluded with an account of how the reversal of global capital flows, which we refer to symbolically as the birth of the Global Minotaur, enabled the United States to regain its ‘competitiveness’ and redouble its hegemony because of (rather than despite) its deficits. In Paul Volcker’s frank words, ‘external financing constraints were something that ordinary countries had to worry about, not the unquestioned leader of the free world, whose currency everybody wanted’.53

Our argument in Chapter 11 was that the Global Minotaur was financed by a tsunami of capital that raced across both oceans towards the United States. Figure 12.1 focuses on the 1980 to 2008 period. The first bar in each year depicts the US current account (or trade); the second bar corresponds to the current account of both the European Union and Japan (the two former pro feges of the United States); last, the third bar concerns the current account of Asia and the oil exporters in toto.

We note that, once the early 1980s recession was overcome (to a great extent as a result of a large boost of military spending by the Reagan administration), the Global Minotaur

The Global Minotaur’s evolution The current accounts of the USA, the EU & Japan economies and the Asian & Oil exporting countries

2 r-—... .............—------—-—-—

-2

Figure 12.1 How the EU and Japan on the one hand and Asia and oil exporters on the other financed the US current account deficit.

Note: (First bar: The US current account;

Second bar: The combined current accounts of EU & Japan;

Third bar: The current account of emerging Asia & oil exporters)

got underway. In 1985 it was financed almost exclusively by Europe and Japan.14 In 1990 a mini-recession squeezed the imbalances slightly (as recessions always do) which, however, blew out again once the recovery got into its swing. By 1995 again Europe and Japan did the honours. Come 2000, Asia (mainly China) and the oil exporters began to contribute increasingly to the Minotaur's upkeep. From then onwards, while Europe and Japan continued to send their capital tributes to Wall Street, the burden shifted emphatically towards China, the rest of Asia and the oil exporters. Figure 12.1 offers a more disaggregated snapshot circa 2003.

Figure 12.2 shows that, in 2003 (a typical year during the run up to the Crash of2008, and before the crazed frenzy of the 2006-8 period), the United States Minotaur was devouring more than 70 per cent of global capital outflows. Japan was by far the largest contributor, followed by Germany and China. Mountains of cash flowed to Wall Street and from there to US corporations in the form of equity and loans.

To understand the way that these capital infusions into the US economy caused Wall Street to develop a new role for itself, we need three additional pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. First, there is the increasing profitability of US corporations for the reasons already seen: the constant productivity gains against a background of stagnant real wages (recall Table 11.4, from the previous chapter, and see Figure 12.3 below).

Second, at a time of stagnant wages against a background of a fast increasing pie, and of great social demands to keep-up-with-the-Joneses, the banks’ natural instinct was to use their expanding capital inflows (from abroad but also from the accumulation of domestic profits) in order to extend credit to middle and working class households both in the form of mortgages and of personal loans and credit cards. Those credit facilities were taken up by the relatively low paid on the strength of the hope of rising future wages; a hope sustained by the discourse, especially in the media, of an American economy experiencing high growth rate; a hope, however, that was forever crushed by the ruthlessness of their personal, local reality.

Capital inflows in %, 2003

11 r> — -

b USA a UK a Australia

a Spain, Italy, Greece and Mexico sa Other

Capital outflows in %, 2003

|

a Japan | |

|

s Germany | |

|

8 |

China |

|

w |

■ Russia |

|

w |

m Other |

58

Figure 12.2 Global capital inflows and outflows, 2003.

Source: IMF Global Financial Stability Report

Note: The "other’ surplus countries that contributed 58% of capital exports (see lower diagram) were the following Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Canada *

US real corporate profitability index

1961-1970 1971-1980 1981-1990 1991-2000 2001-2007

Figure 12.3 US corporate profitability (1961-1970 = 100).

The result was debt levels that were rising even faster than the corporations’ profitability throughout the United States and the rest of the Anglo-Celtic world, which was attaching itself to the Minotaur s coat-tails (see Figure 12.4 below).

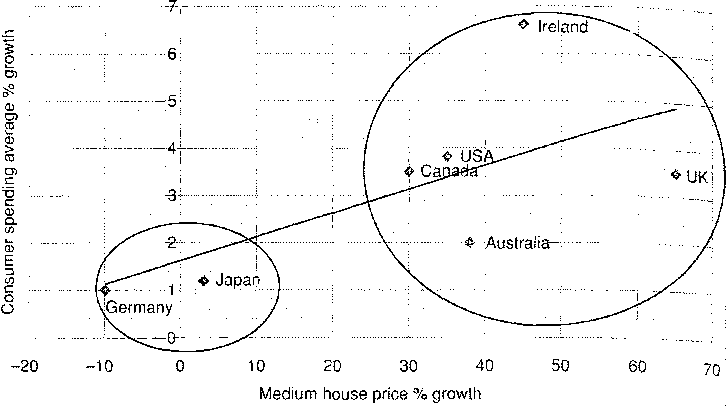

perhaps the most widely understood effect of the Minotaur's rise was its impact on house prices. Anglo-Celtic countries, with the United States naturally leading the way, saw the largest rises in house price inflation. The combination of the capital inflows (see the lower pie chart of Figure 12.1) and the increasing availability of bank loans pushed house prices up at incredible rates. Between 2002 and 2007 the median house rose in price around 65 per cent in Britain, 44 per cent in Ireland, and by between 30 per cent and 40 per cent in the USA, Canada and Australia.

There is an interesting antinomy in the way popular culture, and the financial coninientariat, treat increasing house prices. Whereas inflation is thought of as an enemy of civilisation and a scourge, house price rises are almost universally applauded. Homeowners feel good when estate agents tell them that their house is now worth a lot more, even though they know very well that this is akin to monopoly money; that, unless they are prepared to sell and leave the country (or move into a much smaller house or in a ‘worse’ area), they will never see that ‘value’. Nevertheless, the rise in the asset’s nominal value never fails to make house owners feel more relaxed about borrowing in order to finance consumption. This is precisely what underpinned the stunning growth rate in places like Britain, Australia and Ireland.

Figure 12.5 exposes the correlation between the housing price inflation rate and the growth in consumption. The Angîo-Ceitic countries in which the former was strongest were also the ones in which consumption rose fast. Meanwhile, in the two ex-US protégés, Germany and Japan (the two countries that were financing the Anglo-Celtic deficits through their industrial production, which the Anglo-Celtic countries were, in turn, absorbing) house prices not only did not increase in value but, in the case of Germany, they actually dropped.

Third, the massive and asymmetrical capital flows, together with the increases in corporate profitability, caused a great wave of mergers and acquisitions that, naturally, produced

2500

US real consumer and credit card debt index

0 -j- i i i i

1961-1970 1971-1980 1981-1990 1991-2000 2001-2007

figure J2.4 Personal loans and credit card debt of US households (1961-1970 = 100).

2000

1500

1000

500

Figure 12.5 Link between median house price inflation and the growth in consumer spending 2002-7.

even more residuals for Wall Street operators. In October 1999, Michael Mandel, the chief economic writer of Business Week offered the following opinion; ‘The old market verities apply: as concentration increases, it’s easier for remaining players to raise prices. In the copper industry, the prospect of consolidation helped drive up future prices by more than 20% since the middle of June’ (cited in Foster 2004b).

Indeed, the 1990s and 2000s saw a manic drive towards ‘consolidation’; a euphemism for one conglomerate purchasing, or merging with, another. The purchase of car makers like Daewoo, Saab and Volvo by Ford and General Motors (which was mentioned in Box 12 J ) was just the tip of the iceberg, two periods in capitalist history stand out as the pinnacles of merger and acquisition frenzy: the first decade of the twentieth century (recall Edison and his type of enterprising innovators) and the last decade of the same century.

Reading the 1999 Economic Report of the President, we come across the following lines:

Measured relative to the size of the economy, only the spate of trust formations at the turn of the century comes close to the current level of merger activity, with the value of mergers and acquisitions in the United States in 1998 alone exceeding 1.6 trillion dollars. Corporate mergers and acquisitions grew at a rate of almost 50 percent per year in every year but one between 1992 and 1998. Globally, more than two trillion dollars worth of mergers were announced in the first three quarters of 1999. The leading sectors in this merger wave have been in high technology, media, telecommunications, and finance but mega-mergers are also occurring in basic manufacturing.

[Economic Report of the President (1999), p. 39]

Both ‘consolidation’ waves (of the 1900s and the 1990s) had momentous consequences on Wall Street, effectively multiplying the capital flows that the banks and other financial instituti0118 were handling by a considerable factor. However, the factor involved in the 1990s version was much greater than anything the money markets had ever seen. The reason \vas the Internet. More precisely, the idea of e-commerce mesmerised investors and caused -i areat bonanza that amplified the capital flows, originally due to the Minotaur, beyond the cJniputing capacities of a normal human mind. Box 12.4 offers an example borrowed from Lanchester (2009).13

In 1998 Germany’s flagship vehicle maker, Daimler-Benz, was lured to the United States where it attempted, successfully, to take over Chrysler, the third largest American auto maker. The price the German company paid for Chrysler sounded exorbitant $36 billion, but, at the time, it seemed like a good price in view of Wall Street’s valuation of the merged company that amounted to a whopping SI30 billion! According to Business Week, again (May 18, 1998), the aim of the new colossus was ‘the emergence of a new category of global carmaker at a critical moment in the industry - when there is plant capacity to build at least 15 million more vehicles each year than will be sold’.

In this regard, it sounds like another move along the lines of oligopoly capital's games, no different in spirit from what the conglomerates were doing back in the 1900s. There is however, a difference: for in the 1990s, Wall Street’s valuations had undergone a fundamental transformation (as Box 12.4 illustrates). Motivated by the psychological exuberance caused by the Minotaur-induced capital inflows, Wall Street’s valuations were stratospheric. When Internet company AOL (America On Line) used its inflated Wall Street capitalisation to purchase time-honoured TimeWarner, a new company was formed with $350 billion capitalisation. While AOL produced only 30 per cent of the merged company’s profit stream, it ended up owning 55 per cent of the new firm. These valuations were nothing more than bubbles waiting to burst. And burst they did, just before the Crash of 2008. In 2007, DaimlerChrysler broke up with Daimler, selling Chrysler for a sad $500 million (taking a ‘haircut’ of$15.5 billion, compared to the price it had paid for it in 1998, the lost interest not included); similarly with AOL-TimeWarner. By 2007 its Wall Street capitalisation was revised down from $350 billion to... $29 billion.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the other Anglo-Celtic economy that the Europeans so much admired before 2008, in Britain, a similar game was unfolding at the City of London, In 1976, just before the Minotaur matured fully, the households with the top 10 per cent of marketable wealth (not including housing) controlled 57 per cent of income. In 2003 they controlled 71 per cent. Mrs Thatcher’s government prided itself for having introduced what she called an ‘entrepreneurial culture’, a ‘shareowners’ democracy’. But did she? If we take British households in the lower 50 per cent income bracket and look at the proportion of the nation’s speculative capital that they owned and controlled, in 1976 that was 12 per cent. In 2003 it had dropped to 1 per cent. By contrast, the top 1 per cent of the income distribution increased its control over speculative capital from 18 per cent in 1976 to 34 per cent in 2003.

Beyond statistics, two concrete examples illustrate well the change in capitalist logic in the time of the Minotaur. The City of London, attached every so firmly to Wall Street, could not but emulate the spirit of financial isation that first emerged in the United States in response to the large capital inflows from the rest of the world. Take for instance Debenhams, the retail and department store chain. It was bought in 2003 by a group of investors. The new owners sold most of the company’s fixed assets, pocketed a cool £1 billion and re-sold it at a time of exuberant expectations at more or less the same price that they had paid. The institutional funds that bought Debenhams ended up with massive losses.

Even more spectacularly, in October 2007 the Royal Bank of Scotland put in a winning bid of more than €70 billion for ABN-Amro. By the following April, it was clear that RBS had overstretched itself and tried to raise money to plug holes exposed by the purchase of ABN-Amro. By July 2008 the parts of the merged company that were associated with ABN-Amro were nationalised by the governments of Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg. By the following October, the British government had stepped in to salvage RBS. The cost to the British taxpayer: a gallant £50 billion.

Summing up, the Global Minotaur created capital flows that propelled Wall Street (and, jjv osmosis, the City of London) to the financial stratosphere. The flows came from three m'aiit directions: (a) foreign capital streaming into the United States; (b) US domestic profits aenerated by the Wal-Mart extractive sector; and (c) domestic debt created by middle and working; class America founded on the misplaced faith in an escalator economy that sooner or later would push everyone onto greater heights of prosperity.

These three surging capital streams converged upon Wall Street where they formed a torrent of monies. The resident apparatchiks felt they were the masters of the universe. For at least two decades, the Minotaur conspired to make them believe that no valuation of theirs, however ludicrous in its optimism, could be wrong. It was as if their willpower alone could create new value. Aristotle’s conviction that money making was a telos-\ess activity was lost in the cacophony of the stock exchange and the frenzied activities of the futures’ markets. Greed was not only good but a prerequisite for getting out of bed in the morning.

it was during that postmodern gold fever that Wall Street aimed for a bridge too far. Its building materials had been around for a very long time but it took the Minotaur's energy to bring them together into what the world later came to know as the toxic derivatives.

Double-Wcapitalism begets its own private, toxic ‘money ’

Following the Crash of2008, ‘derivatives’ sound like something the Devil keeps in his toolbox. But to blame the Crash of2008 on derivatives is akin to blaming nitrogen technologies for the carnage in the trenches of the Great War. Of course they wreaked havoc and carnage but they were not the cause. Indeed, before the Minotaur, derivatives were cuddly ‘creatures’ that actually helped hard-working people find a modicum of safety in a viciously uncertain world. The Chicago Commodities Exchange (originally known as the Chicago Butter and Egg Board) allowed long-suffering farmers the opportunity to sell today their next year’s harvest at fixed prices, thus affording them a degree of predictability.

The problem with derivatives is that, like all useful instruments and machines, when they are let loose in a capitalist world, they seem to develop a life force of their own. Of course, they are not to blame. For it is the human mind which, like a demented sorcerer in the clasps of some alien logic (in our case that of capital accumulation), fuses them with superhuman power which then proceeds to hijack it. It all starts in the most innocent of ways but soon the human spirit loses control and becomes the appendage of a nebulous entity with no apparent human agency. Let’s take a look at this process.

Suppose that a cash-strapped artist offers you a futures contract, or ‘option’ to buy a painting that he/she has not yet painted. The option is worth $1,000 now and the price you will pay for the painting when the painting is complete will be determined by an independent art dealer’s valuation. Once you purchase the option, you can, of course, simply sit there and wait for the painting to materialise, at which point you will need to dish out the remaining dollars for the painting itself.

Alternatively, you can sell the option to someone else for a lot more than $1,000 if, for example, an older work by the same artist has just done well at auction; and vice versa. If the artist’s fortunes dip in the stock exchange of fine work, your option’s market value will have dropped. This is how futures markets also work, the only difference being that the holder of a futures contract is contracted to pay a specified price, regardless of the painting’s eventual valuation by the art dealer.

Defenders of the derivatives’ trade never miss a chance to broadcast the view that derivatives are instruments for reducing the uncertainty that hard-working people take when engaged in producing something (from wheat to a work of art) with a long lead time However, this is where the ‘defence’ usually ends. What the public is rarely told, possibly because it has no interest in the complexity involved, is what happens when derivatives are taken to another realm, one in which the risk reduction does not benefit producers at all

Suppose for instance that the person who wants to reduce risk is not our fine young artist or the hard-working fanner but a speculator who wants to reduce the risk involved in buying a certain bunch of shares currently worth $1 million. However bullish his predictions, he/she wants to reduce his/her risk exposure and to do this he/she buys an option to sell these same shares for $80 thousand. In effect, our speculator has bought some insurance against a fall jn the shares’ value. Like any form of insurance, if the shares’ value rises, as anticipated, the insurance policy w'as a waste of money. But if, say, the shares lose 40 per cent of their value he/she can use his/hfer get-me-out-of-here option and sell the shares at the original price, thus cutting his losses substantially. This is what finance people refer to as hedging.

Hedging has been with us for a long time. But it was the Minotaur that gave it a whollv new role, and a bad reputation after 2008. At a time when the capital flows into Wall Street made its boys and girls feel invincible, masters and mistresses of the universe, it became common for options to be used for exactly the opposite purposes than hedging. So, instead of purchasing an option to sell shares as an insurance in case the shares that they were buying depreciated in value, the smart cookies bought options for buying even more! Thus, they bought their $1 million shares and on top of that they spent another $100 thousand on an option to buy another $1 million. If the shares went up by, say, 40 per cent that would net them a $400 thousand gain from the $ 1 million shares plus a further S400 thousand from the $100 thousand option: a total profit of $700 thousand,

At that point, the seriously optimistic had a radical thought: Why not buy only options? Why bother, with shares at all? For if they were to spend their $1.1 million only on an option to buy these shares (as opposed to $1 million on the shares and $100 thousand on the option), and the shares went up again by 40 per cent, their profit would be a stunning $4.4 million. And this is what is called leverage: a form of borrowing money to bet big time, which increases the stakes of the bet monumentally. Note how the bet above converts a borrowed $1 into a cool profit of more than $4 but, when things go the other way (and shares decline by 40 per cent in value), one is stuck with an obligation to buy shares whose value has fallen, thus converting the borrowed $1 to a debt of more than $4; exactly what one’s mother would have warned against.

Alas, from 1980 onwards, prudential mothers could be, more or less, safely ignored. The Minotaur was generating capital inflows that in turn guaranteed a rising tide in Wall Street. During that time, people ‘in the know’ made a great deal of so-called new financial ‘products’ and ‘innovations’. There was of course no such thing. These ‘innovations’ were just new ways of creating leverage; a fancy term for good old debt. If Dr Faustus had known about all this, he would not have loaned his soul to Mephistopheles in exchange for instant gratification. He would, instead have taken options out on it. Of course, the result would have been the same.

Regarding the notion of ‘financial innovations’, the best line belongs to Paul Volcker. After the Crash of 2008 Wall Street bosses went into damage-control mode, desperately trying to stem the popular demand for stringent regulation of their institutions. Their argument, predictably, was that too much regulation would stem ‘financial innovation’ with dire consequences for economic growth; a little like the mafia warning against law enforcement because of its deflationary consequences. In a plush conference setting, on a cold December 2009 New York night, all the big Wall Street institutions were assembled to hear Paul

Voicker address them. He lost no time before lashing out with the words: ‘I wish someone woiiîd sive me one slued of neutral evidence that financial innovation has led to economic crro\vth; one shred of evidence’. As for the bankers’ argument that the financial sector in the United States had increased its share of value added from 2 per cent to 6.5 per cent, Voicker isked them: ‘is that a reflection of your financial innovation, or just a reflection of what you’re paid?’ To finish them off, he added: ‘The only financial innovation I recall in my long career was the invention of the ATM’.

Leveraging is so risky that it would never have survived as a systemic practice without the Minotaur guaranteeing a steady flow of capita] into Wall Street. Sure enough, even then lots of traders lost lots of money when they overdid it. Nick Leeson, for example, was a vouns trader who in the early 1990s managed to bring down a venerable financial institution, Barines, which had survived through thick and thin for a good two centuries but proved too brittle to endure a young man’s deals in front of a computer screen somewhere in the office maze that is Singapore.

These sudden catastrophic losses were a reminder that the potent combination of derivatives, options, computers and leverage had a great potential for amplifying risk at a time when traders felt that the Minotaur was keeping risks low. However, to turn fully into a WMD (a weapon of mass destruction, as investor Warren Buffet called them) the derivatives-leverage combination required something else; something that was missing before the Minotaur fully fledged: it required some mechanism for pricing them quickly, easily and en masse. That ‘mechanism’ or formula should use as ‘inputs’ the past variation in the price of assets related to the derivative in question, correlations between the prices of different assets, interest rates and some assessment of risk. Its output should be a single price for the derivative in hand. The first such workable formula appeared in the Journal of Political Economy in 1973, Its authors were Fischer Black and Myron Scholes.16 The proposed formula was a major hit. A world of appreciative traders latched on to it and a roaring trade in derivatives began.

The main idea behind these trades was to use scientific methods and raw computer power by which to take advantage of the minutest of arbitrage opportunities (recall the ingenious trading in Radford’s POW camp, Section 6.7, Chapter 6); that is detecting and profiting from tiny differences in prices in different markets, in fact, this is what Barings thought Leeson was doing on its behalf in Singapore: taking advantage of the fact that the average price of Japanese futures (also known as the Nikkei 225) was determined through electronic trading whereas its Singaporean equivalent was manual and slower to adjust. Thus arose a differential in prices, as a result of the different speeds with which prices changed in the two markets. That differential lasted for a few seconds but Leeson’s job was to buy low and sell high within that fleeting window of opportunity.

In 1994, John Meriwhether, who had previously been a star trader and a former vice-chairman of the respected firm Salomon Brothers, set up a new financial firm, also known as a hedge fund, under the name of Long Term Capital Management, in fact, both labels were misleading. LTCM was neither operating on the basis of some long-term strategy for managing other people’s funds (indeed, quite the opposite, it was placing extremely short-term bets on prices movements) nor was it focusing on hedging. The whole point about hedge funds is that, because they deal on a person-to-person basis with super-rich clients, who entrust large sums to them to bet on the markets, hedge funds are not regulated like banks are. That’s their whole raison d’être.

Meriwhether’s idea, in setting up LTCM, was to employ formulae like those that Black, and Scholes had concocted, combine them with high powered computers and then invite rich people to give him their money so as to experiment with the new ‘equipment’ ' a bid to make ‘guaranteed’ profits for everyone involved. The first person he employed was Myron Scholes (Robert C. Merton, who shared with him the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was also on LTCM’s board). With his good contacts, and some early sue cess, Meriwhether attracted a large capital base to LTCM; an impressive $4.87 billion However, drunk' on the early successes that saw LTCM’s heavy leverage strategy yiej^ a fourfold return to its capital, Meriwhether, Scholes and Black threw everything into maximum leverage and a plethora of derivatives. A few years later, LCTM’s risk exposure was somewhere in the order of $1.3 trillion. So, when in 1998 Russia defaulted on its state (or sovereign) debt to foreign financial institutions, a risk that Black and Scholes had never factored in LCTM went belly-up. In the end, the Fed had to step in and organise LCTM’s liquidation.

While LCTM ended up in ruins, it left an important legacy: the powerful combination of leverage and highly complex derivatives whose constituent parts were synthesised by mathematical formulae of an intricacy that not even the mathematicians who concocted them understood fully. However, this was beside the point. Everyone knew that the derivatives were too complex to decipher (see Box 12.5). But their appeal was not harmed by that fact in the slightest. If anything, the very idea that one was buying and selling contracts containing high-order mathematical formulae enhanced their appeal. Of course that was not the main reason why they were all the rage. The main reason was that their value was rising.

Suppose a friend bought a small black box for $ 100 and then found a buyer for it the next day for $400. Then the new buyer sold it on on the following day for $1,000, Later, the little black box was resold a week later for $ 1,800 before, a minute ago, someone offered it to you for $2,000. Would you not want it? Of course you would. Does it matter what’s in it? Of course it does not. Naturally, the question remains: why did such ‘little black boxes’ appreciate in value consistently for two decades? That one wants one if it does appreciate is no explanation of its systematic appreciation.

While it is obvious that people who had no clue of (and cared not one iota regarding) what was hidden inside them, would want them, as long as they were appreciating in value, we still need to explain why they appreciated for so long. Our explanation is the Global Minotaur. In the previous chapter, and the preceding pages of the current one, we argued that the collapse of the Global Plan in 1971 set in train a new dynamic which attracted massive capital transfers from the rest of the world to the United States, but also caused large inflows into Wall Street from within the United States (both in the form of corporate profits and debts by the working and middle classes). These capital flows operated like a perpetual tide that kept pushing all boats up. That buoyant environment was perfect for the incredible enlargement of the derivatives’market witnessed between 1990 and 2008.

Returning to the derivatives themselves, it is helpful to focus on a new form labelled Collateralised Debt Obligation or CDO; the nearest Wall Street ever got to devising a Byzantine instrument. In a manner resembling Hyman Minsky’s point (see Box 7.9, Chapter 7) that a low interest environment causes financial institutions to take greater risks (just like an improvement in a car’s brakes encourages the driver to drive faster), when the Fed’s strategy of dealing with fears of recession following the 1998-2001 various crises17 led to low interest rates, the banks began to lend money more freely and to seek out good returns in new, exotic and some not so exotic places. With real wages under a perpetual squeeze, the greatest demand for these loans came from the have-nots, whose relative desperation translated into a greater readiness to agree to pay higher interest rates.

Of course, poor people were always ready to borrow but the banks’ main principle was never to lend to anyone unless they did not need the money. So, what changed heie?

-fvvo things: first, the United States and its fellow Anglo-Celtic countries, again courtesy of 0ur Minotaur, was experiencing the longest, unbroken period of increasing house prices in history- Second, the poor person’s debt could now be ‘made over’, repackaged within a shiny derivative, complete with rocket science mathematics disguising its unappetising

content.

The long rise in house prices led lenders to feel safe in the thought that if the poor borrowers were to find it hard to meet the repayments due, they could always sell the house and thus repay not only the initial capital plus the interest but also any additional late-payment penalties. This proved correct. But it was only one of the two reasons why the banks lent money to poor home buyers. The second was that the knowledge that, using the magic CDOs, they would not have to bear the risk that their poor customers would default.

This, as the reader will have gathered by now, is the sad tale of subprime mortgages. The story of how Wall Street, not content to process and build upon the tsunami of foreign capital and domestic corporate profits that the Minotaur was pushing its way, tried to profit also from poor people by selling them mortgages which they could never really afford. By 2005, more that 22 per cent of US mortgages were of this subprime variety. By 2007, this had risen further to 26 per cent. All of them were inserted into CDOs before the ink had dried on the dotted line. In raw numbers, between 2005 and 2007 alone, US investment banks issued about $l ,100bn of CDOs.

The trick was to combine in the same CDO subprime with good, or prime, debt; each component associated with a different interest rate. The mathematics behind each of these CDOs was, as ever, complex enough to ensure their inscrutability. However, the mere hint that serious mathematical minds had designed their structure, combining prime and subprime components within the same ‘tranche’, and the solid fact that Wall Street’s respected, and feared, ratings agencies had given them their seal of approval (which came in the form of AAA ratings), was enough for banks, individual investors and hedge funds to buy and sell them internationally as if they were high-grade bonds.

In terms of value, it is estimated that in 2008 the mortgage-backed bonds came to almost $7 trillion, of which at least $1.3 trillion were based mainly on subprime mortgages. The significance of that number is that it is larger even than the total size of the, arguably gigantic, US debt. But to give an accurate picture of the disaster in the making, it is important to project these vast numbers in relation to one another as well as to the level of global income. Only then can we begin to make sense of them. Figure 12.6 is a small step in that direction.

What is clear here is that, as most commentators suggested after 2008, the planet had become too small to contain the derivatives’ market. Whereas in 2003 for every $ 1 earned somewhere in the world there corresponded $1.73 ‘invested’ in some derivative, by 2007 the ratio had changed: almost $8 worth of derivatives corresponded to every dollar made in the real world. So, as if the Minotaur’s actual capital flows (handled mainly by Wall Street and the City of London) were not large enough, the derivatives market regularly experienced trade in the order of more than $1 trillion daily. Of those a small minority were related to US mortgages, and of the latter only one in five were laced with subprime mortgages. However, the inverted pyramid had grown too large and the slightest of pushes threatened to destabilise it.

Most people find it hard to understand how these derivatives grew and grew and grew; how they could end up almost eight times more ‘valuable’ than the whole wide world’s output. One answer to that question is to try to think of derivatives, effectively, as bets. Whether one is betting that the price of pork bellies will rise next June or that a 7+ Richter

Box 12.5 The tricide-up effect and securitisation (the ultimate financial weapon of mass destruction)

Figure 12.6 The World is Not Enough: world income and the market value of derivatives fin $US trillions) at the height of the Minotaur’s reign.

World income! Derivatives i

The trickle-down effect was meant to legitimise reducing tax rates for the rich, by suggesting that their extra cash will eventually trickle down to the poor (see Section 12.1). While all empirical evidence conspires against that hypothesis, despite a sequence of significant tax cuts for the top earners in both the United States and Europe, a quite different effect, the trickle-up effect, was observed in the con-: text of the derivatives market. Securitisation of the unsafe debts of the poor (e.g. the conversion of subprime mortgages into CDOs) had the effect of making the initial lender indifferent to whether or not the loan could be repaid (for she had already sold the debt to someone else). These securitised packages of debt were then sold on and resold at tremendous profit (prior to the Crash of2008). The rich, in an important sense, had discovered another ingenuous way to get richer by trading on commodities packaging the dreams, aspirations and eventual desperation (once the market crashed and the home foreclosures began) of the poorest in society.

Five years before the Crash of2008, investor Warren Buffett, who was at the time the most eminent trader in insurance, said: ‘In my view, derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal. . . there is no central bank assigned to the job of preventing the dominoes toppling in insurance or derivatives’. In a letter to his shareholders, he added:

If our derivatives experience... makes you suspicious of accounting in this

arena, consider yourself wised up. No matter how financially sophisticated

| you are, you can’t possibly learn from reading the disclosure documents of a

j derivatives-intensive company what risks lurk in its positions, Indeed, the more

] you know about derivatives, the less you will feel you can learn from the disclo-

j sures normally proffered you. In Darwin’s words, “Ignorance more frequently

! begets confidence than does knowledge”.

! [Buffet (2010), p. 59]

f

j So, the following question becomes increasingly pressing: why didn’t enough

| people listen to such a consummate insider? Our answer is simple: they were too busy

j making money buying and selling these derivatives!

scale earthquake will hit Tokyo in 2019, some obliging broker will write down a CDO that you can buy, in essence taking this bet. Imagine now a world in which pork bellies more often than not go up in price every June, or that a 7+ Richter scale earthquake hits Tokyo almost every year. In that world, the number of derivatives changing hands would go through the roof, as they did by 2007 (see Figure 12.5). What was it that provided the ‘certainty’ of ever-increasing house prices and an ever-rising stock exchange? The Minotaur, of course.

During that time when money seemed to be growing on trees, traditional companies that actually produced ‘things’ were derided as old-hat. What steel producer, car manufacturer or even electronics company could ever compete with such amazing returns? All sorts of companies wanted to join in! Staid corporations like General Motors for this reason entered the derivatives racket. At first they allowed the company’s finance arm, whose aim was to arrange loans on behalf of customers who could not afford the full price of the firm’s product (e.g. hire purchase for cars), to stick a toe in the derivatives pond. They liked the feeling and the nice greenbacks streaming in. Soon, that finance arm ended up becoming the company’s most lucrative section. So, the firm ended up relying more and more for its profitability on its financial services and less and less on its actual, physical product.

Indeed, some companies that appeared to offer important physical or traditional products and services, in fact were nothing more than purveyors of derivatives. The infamous Enron is an excellent example (see Box 12.6) of how to fraudulently employ derivatives in order to artificially increase profitability with a view to inflating the company’s stock market value, and with a further view to lining management’s pockets with many more millions.

Moreover, even fully legitimate companies that provided a decent service to their customers and had no intention whatsoever to mislead or cheat anyone, they too were lured into using derivatives as part of their normal operations. Northern Rock, the bank whose collapse in a sense started the ball rolling in 2008, is the obvious example (see Box 12.7).

Summing up this brief foray into the smoke and mirrors of the modern derivatives’ marketplace, the reason why an initially innocuous type of contract turned into a potential weapon of mass financial annihilation is threefold.

First, while billeted as an instrument for reducing risk, it can just as easily be employed as an amplifier of gambles and an enlarger of the risks involved. Unlike the fool who has to raise money from friends and family to play at the casino, the derivative buyer can gamble now without much money but be just as readily saddled in the future with a debt that no casino can ever hope to unload on a human being.

Second, derivative trading is off the books. What this means is that there was no mechanism for even knowing what derivatives were being traded, let alone a mechanism for

Box 12.6 Enron {

I

I

In the 1990s, Enron was corporate America’s blue-eyed company. Voted America's I Most Innovative Company six times in row, by no other than the readers of Fortune i magazine, it exerted a powerful influence in what used to be called (prior to the ^ Minotaur’s successful push to privatise them) public utilities: electricity generation j natural gas distribution, water management and telecommunications. Connected as it I was to the real, old-fashioned sectors involving cables, water pipes, etc., no one had i imagined that Enron was no more than a house of cards made of derivative paper. I When it went bankrupt in 2001, it had 21 thousand employees on its payroll in 42 I countries. Most lost not only their due wages but also their pensions (some only j months away from retirement, as the company had already used up the pension funds ! for other, mostly illegal, purposes). j

To cut a long story short, Enron lied about its revenues, its costs and its assets thus presenting a bottom line that was as impressive as it was fraudulent. Arthur Andersen, the international accounting firm that audited its books, was successfully prosecuted by US authorities for wilfully damaging evidence of its part in Enron’s false accounts. As a result, Andersen followed Enron into oblivion. Two major companies thus perished.

From the perspective of this chapter what matters is the manner in which Enron and Andersen managed to hide the tmth, that the former had no clothes, for so long. They did this simply by employing derivatives that never appeared as such on the company’s balance sheets. For instance, just before the annual accounts were filed, the company would package a debt as a derivative, sell it to itself and thus manage to remove that debt from the liabilities segment. Soon after the accounts were filed, it would restore it. And similarly with revenues. When planning to build a power station that would start bringing in actual revenues in ten years’ time, Enron would ‘create’ a derivative whose present value it would immediately list in the current assets column, thus inflating its revenues and profit. As long as no one noticed, these ‘beautiful numbers’ boosted Enron’s equity (or market value at the Wall Street stock exchange) and, as a result, Enron acquired greater power to acquire other companies (on the basis of that increased equity) to further inflate its bottom line.

Box 12.7 Northern Rock

Northern Rock is a bank doing most of its business in the north east of England. A medium-sized mortgage lender, it was doing brisk business for a while. Using the power of the Internet, it allowed customers a fast and easy service that seemed, at the time, like a great innovation. The fact that its interest rates were slightly below that of the more established banks seemed logical given its lean, digitised operation and the lower costs it faced in terms of branch rentals and staff wages. In general, Northern Rock was liked by its customers who felt better treated than they had been previously by the four big high-street banks that dominated previously.

As in the United States, so too in Britain, mortgage lenders leamt the trick of immediately converting the loans (given to customers to buy a house or business) into CDO-like derivatives to be sold on. Northern Rock was not at all exceptional in doing this. But it was exceptional in another regard: its Achilles ’ heel was that the bank drew less than 30 per cent of the money deposited with it by customers. The rest it was rais-iim from other banks on very, veiy short-term contracts. Imagine that: Northern Rock would lend Joe Bloke £100 thousand for, say, 20 years but it would do so by borrowing the money at rock bottom interest rates for a night or two, then re-borrowing it again, and again, and again. Needless to say, Northern Rock had good cause to bundle this £100 thousand into some CDO and sell it off as quickly as possible. In short, Northern Rock’s continuing operation required that (a) short-term interest rates remain low, (b) other banks were happy to lend it the money from day to day and

(c) the CDO market continued to absorb newly issued CDOs. Alas, in 2008 all three conditions stopped holding and the rest, as they say, is history.1

Note

1 Even though, unlike in the United States, in the case of Northern Rock, the underlying mortgages were never of the subprime variety! indeed, to this day, the vast majority of Northern Rock mortgage holders continue to meet their repayments as agreed in their contracts.

regulating them. The whole regulatory framework that the New Dealers put in place, after 1932, in order to prevent banks from speculating with their customers’ hard-earned money, had been tom asunder both by the Clinton administration in the 1990s (with Larry Summers at the helm) and, quite independently, by the rise of the derivatives market; a market that is almost completely underground and shrouded in secrecy.

Third, because of both the opacity and the immensity of this market, no one could possibly know how a meltdown in parts of that market would affect the rest of the global financial system. The very size of the right-hand side bar in Figure 12.6 suggests that the mighty would easily be felled if only a small component of that market were to fail. As it ;turned out, it only took a little over $1 trillion of it (the subprime mortgage-backed bonds) to slip before the whole edifice came tumbling down.

The above is well known to anyone who has been following the financial press. There are, however, two crucial truths that cannot be understood satisfactorily outside the context of our Modern Political Economics. One is the fact that, without the Global Minotaur's rise (which we have been tracking in Book 2 in some detail), the prerequisites of the drive towards financialisation (namely the massive capital flows through Wall Street) would not have been satisfied and the last few figures would not have looked as they do. The second fact takes us back to Chapter 7 and the Quantity Theory of Money, of which free marketeers have been so enamoured for at least two centuries.

According to the latter, too much money flooding into the economy is a recipe for disaster; for hyper-inflation and the loss of the market’s capacity to send meaningful signals to producers and consumers on what to produce and what to economise. The reader will also recall Friedrich von Hayek’s, admittedly extreme, position that the state could not be taisted to produce money, because collective or political institutions simply lack the nous to determine the appropriate quantity of money (recall Box 7.12). His recommendation? To let private firms, banks and individuals issue their own money and then allow the market, through good old-fashioned competition, determine which of these competing currencies the public trusted more.

Now, consider the role of the zillions of CDOs that flooded the financial system in the decade 1998-2008. What were they? In theory, the CDOs were options or contracts. In reality, and since no one knew (or really cared to know) what they contained, they acted as a form of private money that financial institutions and corporations used both as a medium of exchange and a store of value. Friedrich von Hayek ought to have been pleased!

This flood of a form of private money, over whose quantity and worth no one had the slightest control, played an increasing role in keeping global capitalism liquid in the era of the Global Minotaur. So, when the plug was pulled in 2008, and all that private money disappeared from the face of the earth, global capitalism was left with what looked like a massive liquidity crisis. It was as if the lake had evaporated and the fish, large and small, were quivering in the mud.

Kl £-50:1

A prudent person might imagine that Goodwidget is probably a safer investment. However, that thought was routinely dismissed as fuddy-duddy; as backward looking and insufficiently tuned into E-widget’s bright future. So, here is how Wall Street thought: suppose E-widget were to use its superior equity to buy Goodwidget. What would be the value of the merged company? Should we just add up the two companies’ equities or capitalisations ($10 billion and S5 billion = $15 billion)? No, that would be too timid. Instead, Wall Street did something cleverer. It added the earnings of the two companies ($700 million + $200 million - $900 million) and multiplied it with E-widgefs capitalisation to earnings ratio. This small piece of arithmetic yielded a fabulous number: 50:1 times $900 million - 45 billion!

Thus, the new merged company was valued at $30 billion more than the sum of the equity or capitalisations of the two merged companies (a sudden leap of 300 per cent). Needless to say, the fees and commissions of the Wall Street institutions that saw the merger through those rose-tinted lenses was analogous to the marvellous big figure at which they had miraculously arrived.