12.5 Crash and burn: Credit crunch, bailouts and the socialisation of everything

We are now in the phase where the risk of carrying assets with borrowed money is so great that there is a competitive panic to get liquid. And each individual who succeeds in getting more liquid forces down the price of assets in the process of getting liquid, with the result that the margins of other individuals are impaired and their courage undermined. And so the process continues.... We have here an extreme example of the disharmony of general and particular interest.

John Maynard Keynes, ‘The World’s Economic Outlook’,

Atlantic Monthly, (1932)

Box 12.15 Rats abandoning a sinking ship (while German bankers were jumping aboard)

In mid-2010 the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), whose remit is to regulate Wall Street and the financial sector in general, began legal proceedings against Goldman Sachs (GS), Wall Street’s most successful merchant bank. The offence over which GS was taken to task concerns a particular CDO called Abacus 2007-ACl that GS ‘constructed’ and sold at the beginning of 2007, just as the CDO market was about to go into meltdown. The essence of the charge is that GS was knowingly flogging a dead horse. In fact, it is a little worse than that: the SEC is alleging that GS had a hand in the killing of a horse and then trying to market its carcass as a boisterous stallion!

According to the SEC, GS created Abacus in association with a hedge fund called John Paulson & Co. The hedge fund chose a series of unsafe subprime mortgages that it knew were about to default and asked GS to infuse them into Abacus. Why did it do that? Because it wanted to bet against Abacus, the very CDO it helped create! Rather than take the small risk of betting against an unknown CDO, it chose to have GS create a duff one, ensuring that any bet against it would have been lucrative (as. long as no-one else, except GS and John Paulson & Co, knew that Abacus was dead in the water).

Technically, the bet against Abacus meant that John Paulson & Co took a CDS out against Abacus (i.e. an ‘insurance policy’ that would pay good money if those whose bought Abacus lost their money - see Box 12.12). The problem of course was to find gullible buyers that would purchase Abacus no questions asked. That task fell on GS, the merchant bank which, according to the SEC, recommended Abacus to specific clients leading them to believe that it too, GS, would be buying into Abacus. Of course, GS had no such intention. With their accomplice, John Paulson & Co, they took out loads of CDSs against Abacus netting a nice little earner when the mortgages within Abacus failed (as planned).

Merchant banks, with GS at the forefront, made billions creating (or ‘structuring’) CDOs and selling them. That was well known. The Abacus case reveals an even darker side of this ‘market’: merchant banks creating financial products that were designed to fail so that they would collect the insurance. This is no different whatsoever, at least in principle, to the following scenario: imagine an aircraft manufacturer that is approached by a friendly insurer who suggests that it builds a faulty aircraft, one that is designed to crash, while the insurer writes a policy on behalf of its passengers. Only the insurer will ensure that the insurance monies will not go to the victims’ families but will be, instead, collected by the insurer himself and the aircraft manufacturer with whom they will split the payout.

Let us now turn to the German connection. One of the main institutions that bought Abacus was called Rhinebridge, a subsidiary, or rather a SIV (a structured investment vehicle) of German bank IKB which used to be a conservative outfit lending, mainly, to Gennan small- and medium-sized firms. What did such a parochial little bank from middle Germany know about Abacus? Exactly nothing, is the honest answer. Except that it knew that those before it who had bought CDOs from GS had profited greatly. It is not that the IKB did not try to look into Abacus to see what was under the bonnet. Its financial engineers and accountants took a good look. But they could not work out

I its contents, for that was GS’ great talent: to instil such mindboggling complexity into I its CDOs that not even a god could decipher them.

I GS was not an exception to the rule. Most, if not all, merchant banks worked closely I with hedge funds to similar effect.1 Especially in the months leading to the Crash of j 2008, these smart operators knew that there was something rotten in the mortgage j backed bonds that they had helped create. So, they went into a flurry of creating new I CDOs that would unload the truly dangerous tranches of mortgages off their own books to those of unsuspecting buyers. In the process they took out CDSs to profit from the transaction on top! Infinite ‘innovation’ went into similar schemes; as Ford and Jones (2010) demonstrate:

...investment banks were interested in the possibility of using CDOs to offload the toxic risks in rivals’ balance sheets on to clients. As Goldman’s Fabrice Tourre put it in an e-mail to his superiors at the end of 2006, one of the big opportunities lay in ‘Abacus-rental strategies.,, [where] we ‘rent’ our Abacus platform to counterparties focused on putting on macro short in the sector7. Decoded: Goldman would sell CDOs staffed with other investment banks’ toxic waste, allowing them to short it., ,.2 The banks didn’t want to look as if they were shorting themselves,’ says one subprime investor. ‘So bank A helped bank B get short and then bank B helped bank C and so on. Unless you were very close to the market you wouldn’t get it.3

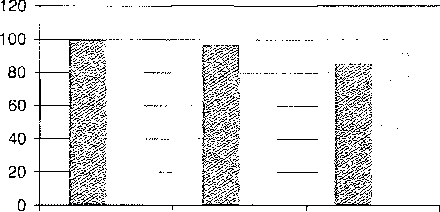

CDO new issues {$ billions) 630

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Figure 12.7 The triumph of financialisadon.

Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association)

When the inevitable happened, IKB ran to the German government and its parent bank (KfW) for help. The bill for keeping it alive came to €1.5 billion. It was the tip of the iceberg. The Global Minotaur, unbeknownst to the German people, and to most of its politicians, had infected the German capital with the virus of financialisation. When that disease became fully blown, Gennany suffered considerably from the consequences. We return to this in Section 12.6.

Notes ’

1 Indeed, we could have used Morgan Stanley’s 'Baldwin deals’ as another example of T merchant bank that bets against its own product. As Bloomberg reported on 14 May 20 n> i ‘In June 2006, a year before the subprime mortgage market collapsed, Morgan Stanhv ^ created a cluster of investments doomed to fail even if default rates stayed low - then ^ bet against its concoction. Known as the Baldwin deals, the SI 67 million of synthetic ? collateralised debt obligations had an unusual feature, according to sales documents. Rather -than curtailing their bets on mortgage bonds as the underlying home loans paid down, the -CDOs kept wagering as if the risk hadn’t changed. That left Baldwin investors facins losses f on a modest rise in US housing foreclosures, while Morgan Stanley was positioned to «ain f [Shenn and Moore (2010)] c j

2 The expression ‘to short’ a financial simply means to bet against it. Usually this is done either 1 by taking a CDS out on it (that is, an insurance policy that pays you if Jill fails, crashes ! dies,...) or, in the case of shares in company X, renting someone’s else’s X shares, selling i them now, collecting the money and then buying them back before you have to return them * to their owner. If, meanwhile, the share price has fallen, you pocket the difference (and pay a small rental fee to the owner).

3 Ford and Jones, 2010.

Children leam from a young age the dynamics of piles of building blocks. l'he\ pik cube on top of another cube and keep doing it until their little tower of cubes nipple ,^¡.7: at which point they emit a happy giggle and start afresh. If only bankers and hedge fund managers were equally rational!

The moment one asset bubble bursts, a new one begins slowly to emerge snniewhe:;:: often in exactly the same place. But this is where the similarity with the liken\ yanv ends. While the children know full well that their new pile will come to the same end as the previous one, in asset markets the supposedly super-smart operators sonichiuv corn mu: themselves that this-time-it-will-be-different. They succeed in believing that they are living the dream of some new paradigm?9

The longer the rally lasts, and the more absurd their profits, the more corn inceci \\K} become that it will last forever. Moreover, this growing conviction is cemented in;n pi.ice with the attendant belief that their new fabulous payoffs are deeply deserved and i'ulK justified by the bout of psychic anguish they had experienced during the p rev ion > co!lap>e. Hie smartest cookies in the business, who recognise first the signs of a potential fresh calamity, turn their faith in the righteousness of their cause into the most ruthless slash-and-hurn practices (e.g. aggressive short-selling, financial cannibalism of the sort described in Box 12,1$ above) which not only bring the next crash forward but also amplify its catastrophic force.

The story of how the Crash of2008 began is now the stuff of legend. Piles of books have been written on it and stacked on the shelves of university libraries, in airport news agencies, at the stalls of leftist groupings plying their revolutionary wares on street corners, etc.40 We shall, therefore, desist a precise chronological account (see Box 12.16 for an ascetic timeline), Suffice to remind the reader that the ‘deconstructin’ began in the shadowy world ot CDO trading, particularly those containing vast tranches of subprime mortgages.

As Section 12.3 argued, Wall Street had managed to set up a parallel monetary system, based on the use of CDOs as a form of private money underwitten by the capital inflows* toward the Global Minotaur. This parallel ‘monetary system’ was based on a game of pass-ing-the-parcel from one financial institution to the next, without a care in the world about what was in the parcel. Alas, the contents mattered.

When in 2001 a bubble in Wall Street burst (a bubble centred upon the so-called dot.com or Tsiew Economy craze), Alan Greenspan, Paul Volcker’s successor as the Fed’s Chairman, tflok fri?ht that a recession would ensue (like that of the 1979-83 or the 1987, 1991 and 1998 •irieties which he had himself seen off, with considerable success). He responded, quite reasonably, by loosening monetary policy substantially; exactly as he had done in 1987, ¡991 and 1998. To that effect, US interest rates fell until in 2004 they were at a rock bottom ] per cent.

Greenspan’s policy seemed to make perfect sense. In fact his reputation as an artful and astute monetary policy tsar was built on his success at exactly such a move back in October j9S7 (immediately after his appointment), when his quick-fire response to Black Monday (i e a quick reduction in interest rates and a large injection of liquidity into the financial sector), averted a recession and restored confidence in Wall Street before 1987 was out. Similar episodes in 1991 and 1998 turned him into the Fed’s unrivalled sage. His 2001 seemed for a long while to have met with similar success, judging by the impressive post-^001 growth figures. By the time of his retirement, in 2007, Alan Greenspan was feted as a demi-god.

Alas, 2001 was no 1987. The main difference was that in 1987 the financial sector had not yet built up a whole new parallel system ofprivate money on the back of the Global Minotaur. The latter had managed to stabilise the US balance of payments but had not yet created the dynamic of financialisation that, by the late 1990s, would erect a parallel monetary system on the foundations of the derivatives’ market. Thus, when the Fed pumped liquidity into the financial system in 1987, it simply helped kick-start a stalled engine. In sharp contrast, in 2001, the injection of liquidity and the low interest rates, in conjunction with the Minotaur's exploding vivacity, helped create a monster that was to turn on its creator very, very viciously six or seven years later.

By 2004, Greenspan had got a whiff of the growing bubble. He decided to go about its gradual deflation by increasing US interest rates slowly but steadily. Unfortunately, the parallel private monetary system had in the meantime grown too large on the strength of the Minotaur, the laughably large amounts of leverage chosen by Wall Street operators (30:1 was common) and, of course, the proliferation of securitised derivatives, that is CDOs and their offshoots. The quantity of private money in the global economy was so great that it became impossible to find a rate of interest rate rises that would, at once (a) deflate the Bubble and (b) avert a Crash. Thus, Wall Street’s game began to unravel.

By 2006, US interest rates had risen to 5.35 per cent. The immediate effect was a downturn in the US housing sector. Some homeowners who were sitting on the most unaffordable {to them) subprime mortgages defaulted. Soon the trickle of defaults turned into a torrent; one that Dr Li’s formula (given the assumed constancy of parameter y) could not cope with. The value of CDOs crashed and soon the market for CDOs ground to a halt. Suddenly the merry-go-round game of profiting through passing CDOs from one financial institution to another turned into a desperate, cut-throat game of musical chairs, in which CDO holders (mainly the financial institutions) were going around in circles aghast at the realisation that someone had removed all the chairs.

In a few short weeks, the private money that Wall Street had created in the wake of the Global Minotaur's capital flows had turned into hot ashes. The fact that the world’s most venerable financial institutions had grown fully to depend on that money meant one thing: The global financial system had come to a standstill. No one would lend to anyone, fearing that the borrower had a huge exposure to the worthless CDOs. Capitalism was facing a crisis b‘gger than that of 1929.

It was at that point that the state, with the US state at the forefront, stepped in with the greatest government intervention humanity has ever seen. In a few months, more capitalist institutions were socialised than in Lenin’s Soviet Russia. Ironically, this wave of socialisa, tion happened at the behest of the world’s strongest opponents of state intervention. At the very least, history retains its sense of humour.

Box 12.16 The diary of a Crash foretold ^

2007 ~ The canaries in the mine

April - A mortgage company that had issued a great number of subprime mortgages. New Century Financial, goes bankrupt with reverberations around the whole sector. i

July - Bear Stearns, the respected merchant bank, announces that two of its hedge funds will not be able to pay their investors their dues. The new Chairman of the Fed, Ben Bernanke (who had only recently replaced Alan Greenspan) announces that the ; subprime crisis is serious and its cost may rise to $100 billion.

August - French merchant bank BNP-Paribas makes a similar announcement to that of Bear Stearns concerning two of its hedge funds. Its explanation? That it can no longer value its assets. In reality, it is an admission that the said funds are full of CDOs ! whose demand has fallen to precisely zero, thus making it impossible to price them. ! Almost immediately, European banks stop lending to each other. The ECB {European ! Central Bank) is forced to throw €95 billion into the financial markets to avert an immediate seizure. Not a few days go by before it throws a further €109 billion into the markets. At the same time, the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada, the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Japan begin to pump undisclosed billions into their financial sectors. On 17 August, Bernanke reduces interest rates slightly, demonstrating a serious lack of appreciation of the scale of the impending doom.

September - The obvious unwillingness of the banks to lend to one another is revealed when the rate at which they lend to each other {Libor) exceeds the Bank of England’s rate by more than I per cent (for the first time since the South-East Asian crisis of 1998). At this point, we witness the first run-on-a-bank since 1929. The bank in question is Northern Rock (see Box 12.7). While it holds no CDOs or subprime mortgage accounts, the bank relies heavily on short-term loans from other banks. Once this source of credit dries up, it can no longer meet its liquidity needs. When customers suspect this, they try to withdraw their money, at which point the bank collapses before being restored to ‘life’ by the Bank of England at a cost in excess of £15 billion, j Rocked by this development, Bernanke drops US interest rates by another small j amount, to 4.75 per cent while the Bank of England throws £10 billion worth of liquid- j ity into the City of London. !

October - The banking crisis extends to the most esteemed Swiss financial institu- j tion, UBS, and the world takes notice. UBS announces the resignation of its chairman j and CEO who takes the blame for a loss of $3.4 billion from CDOs containing US j subprime mortgages. Meanwhile in the United States, Citigroup at first reveals a loss j of $3.1 billion (again on mortgage backed CDOs), a figure that it boosts by another | $5.9 bn in a few days. By March of 2008, Citigroup has to admit that the real figure is j

a stunning loss of $40 bn. Not to be left out of the fracas, merchant bank Merrill Lynch announces a S7.9 billion loss and its CEO falls on his sword.

December - An historic moment arrives when one of the most free-marketer opponents of state intervention to have made it to the Presidency of the United States, George W. Bush, gives the first indication of the world’s greatest government intervention (including that of Lenin after the Russian revolution). On 6 December President Bush unveils a plan to support a million of US homeowners to avoid having their house confiscated by the banks (or foreclosure, as the Americans call it). A few days later, the Fed gets together with another five central banks (including the ECB) to extend almost infinite credit to the banks. The aim? To address the Credit Crunch; i.e. the complete stop in inter-bank lending.

2008 - The main event

January - The World Bank predicts a global recession, stock markets crash, the Fed drops interest rates to 3.5 per cent, and stock markets rebound in response. Before long- however, MBIA, an insurance company, announces that it lost $2.3 billion from policies on bonds containing subprime mortgages.

February - The Fed lets it be known that it is worried about the insurance sector while the G7 (the representatives of the seven leading developed countries) forecasts the cost of the subprime crisis to be in the vicinity of $400 billion. Meanwhile the British government is forced to nationalise Northern Rock, Wall Street’s fifth-largest bank, Bear Stearns (which in 2007 was valued at $20 billion) is absorbed by JP MorganChase, which pays for it the miserly sum of $240 million, with the taxpayer throwing in a subsidy in the order of... $30 billion.

April -It is reported that more than 20 per cent of mortgage ‘products’ in Britain are withdrawn from the market, along with the option of taking out a 100 per cent mortgage. Meanwhile, the IMF estimates the cost of the Credit Crunch to exceed $1 trillion. The Bank of England replies with a further interest rate cut to 5 per cent and decides to offer £50 billion to banks laden with problematic mortgages. A little later, the Royal Bank of Scotland attempts to prevent bankruptcy by trying to raise £12 billion from its shareholders, while at the same time admitting to having lost almost £6 billion in CDOs and the like. Around that time house prices start falling in Britain, Ireland and Spain, precipitating more defaults (as homeowners in trouble can no longer even pay back their mortgages by selling their house at a price higher than their mortgage debt).

May - Swiss bank UBS is back in the news, with the announcement that it has lost $37 billion on duff mortgage-backed CDOs and its intention to raise almost $16 billion from its shareholders.

June - Barclays Bank follows the Royal Bank of Scotland and UBS in trying to raise £4.5 billion at the stock exchange.

July - Gloom descends upon the City as the British Chamber of Commerce predicts a fierce recession and the stock exchange falls. On the other side of the Atlantic, the government begins massively to assist the two largest mortgage providers (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). The total bill of that assistance, takes the form of cash injections and loan guarantees of $5 trillion (yes dear reader, trillion -this is not a typo!), or around one tenth of the planet’s annual GDP.

August - House prices continue to fall in the United States, Britain, Ireland and Spain, precipitating more defaults, more stress on financial institutions and more help from the taxpayer. The British government, through its Chancellor, admits that the recession cannot be avoided and that it would be more ‘profound and long-lasting’ than hitherto expected,

September - The City of London stock market crashes while Wall Street is buffeted by official statistics revealing a spiralling level of unemployment (above 6 per cent and rising). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are officially nationalised and Henry Paulson, President Bush’s Treasury Secretary and an ex-head of Goldman Sachs, hints at the grave danger for the whole financial system posed by these two firms’ debt levels. Before his dire announcement has a chance of being digested. Wall Street giant Lehman Brothers confesses to a loss of $3.9 billion during the months June, July and August. It is, of course, the iceberg’s tip. Convinced that the US government will not let it go to the wall, and that it will at least generously subsidise someone to buy it, Lehman Brothers begins searching for a buyer. Britain’s Barclays Bank expresses an interest on condition that the US taxpayer funds all the potential losses from such a deal. Secretary Paulson, whose antipathy of the CEO of Lehman’s since his days at Goldman Sachs is well documented, says a rare ‘No’. Lehman Brothers thus files for bankruptcy, initiating the crisis’ most dangerous avalanche. In the meantime, Merrill Lynch, which finds itself in a similar position, manages to negotiate its takeover by Bank of America at $50 billion, again with the taxpayer’s generous assistance; assistance that is provided by a panicking government following the dismal effects on the world’s financial sector of its refusal to rescue Lehman Brothers.

When it rains it pours. The bail out of Merrill Lynch does not stop the domino effect. Indeed one of the largest dominoes is about to fall: the American Insurance Group (AIG). When it emerges that A1G is also on the brink, the Fed immediately puts together an $85 billion rescue package. Within the next six months, the total cost to the taxpayer for saving AIG from the wolves rises to an astounding $143 billion. While this drama is playing out in New York and Washington, back in London the government tries to rescue HBOS, the country’s largest mortgage lender, by organising a £12 billion takeover by Lloyds TSB. Three day later in the United States-Washington Mutual, a significant mortgage lender with a valuation of $307 billion, goes bankrupt, is wound down and its carcass is sold off to JP MorganChase.

On 28th of the month, Fortis, a giant continental European bank, collapses and is nationalised. On the same day, the US Congress discusses a request from the US Treasury to grant it the right to call upon $700 billion as assistance to the distressed financial sector so that the latter can ‘deal’ with its ‘bad assets’. The package is labelled the Paulson Plan, named after President Bush’s Treasury Secretary. In the language of this book, Congress was being asked to replace the private money that the financial sector had created, and which turned into ashes in 2007/8, with good, old-fashioned public money.

Before the fateful September is out, the British government nationalises Bradford and Bingley (at the cost of £50 bn in cash and guarantees) and the government of Iceland nationalises one of the small island nation’s three banks (an omen for the largest 2008-induced economic meltdown, by per capita impact). Ireland tries to steady savers’ nerves by announcing that the government guarantees all savings in all banks trading on the Emerald Isle. On the same day Belgium, France and Luxembourg put €6.4 billion into another bank, Dexia, to prevent it from shutting up shop.

The date is 29 September but this particularly recalcitrant September is not done yet. In its thirtieth day the big shock comes from the US Congress, which rejects the Treasury’s request for the $700 billion facility with which Paulson is planning to save Wall Street. The New York stock exchange falls fast and hard and the world is enveloped in an even thicker cloud of deep uncertainty.

October - On 3 October the US Congress succumbs to the pressing reality and in the end passes the $700 billion ‘bait out’ package, after its members have secured numerous deals for their own constituencies. Three days later the German government steps in with €50 billion to save one of its own naive banks, Hypo Real Estate. While painful for a country that always prides itself as supremely prudent, the pain comes nowhere close to that which Icelanders are about to experience. The Icelandic government declares that it is taking over all three banks given their manifest inability to continue trading as private lenders. It is clear that the banks’ bankruptcy will soon bankrupt the whole country, whose economic footprint is far smaller than that of its failed banks. Iceland’s failure has repercussions elsewhere, in particular in Britain and Holland where the Icelandic banks are particularly active. Many of the UK’s local authorities have entrusted their accounts to Icelandic banks (in return for high-ish interest rates) and for this reason their failure adds to the malaise. On 10 October, the British government throws an additional £50 billion into the financial sector and offers up to £200 billion in short-term loans. Moreover, the Fed, the Bank of England, the ECB and the Central Banks of Canada, Sweden and Switzerland cut their interest rates at once: the Fed to a very low 1.5 per cent, the ECB to 3.75 per cent, and the Bank of England to 4.5 per cent.

Two days later, the British government decides that the banks are in such a state that, despite the huge assistance they have received, they require a great deal more to stay in business. A new mountain of cash, £37 billion, is to be handed out to the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds TSB and HBOS. It is not a move specific to Britain. On 14 October, the US Treasury uses $250 billion to buy chunks of different ailing banks so as to shore them up. President Bush explains that this intervention is approved in order to ‘help preserve free markets’. George Orwell, the British author of 1984, would have been amused with this perfect example of naked double-speak.

It is now official: both the United States and Britain are entering into a recession, as the financial crisis begins to affect the real economy. The Fed immediately reduces interest rates further, from 1.5 per cent to 1 per cent.

November - The Bank of England also cuts interest rates, though not to the same level (from 4.5 per cent to 3 per cent), as does the ECB (from 3,75 per cent to 3.25 per cent). The Crash is spreading its wings further afield, sparking off a crisis in Ukraine (which prompts the IMF to lend it $16 billion) and causing the Chinese government to set in train its own stimulus package worth $586 billion over two years; money to be spent on infrastructural projects, some social projects and reductions in corporate taxation. The Eurozone announces too that its economy is in recession. The IMF sends $2.1 billion to bankrupt Iceland. The US Treasury gives a further $20 billion to Citigroup (as its shares lose 62 per cent of their value in a few short days). The British

government reduces VAT (from 17.5 per cent to 15 per cent). The Fed injects yet \ another $800 billion into the financial system. Finally, the European Commission ! approves a plan that will see €200 billion being spent as a Keynesian stimulus I injection to restore aggregate demand. i

December - The month begins with the announcement by the respected US-based | National Bureau of Economic Research that the US economy’s recession had begun as early as December 2007. During the next ten days, France adds its own aid package for its banking sector, worth €26 billion, and the ECB, the Bank of England, plus the Banks of Sweden and Denmark, reduce interest rates again. In the United States, the public is shocked when the Bank of America says that its taxpayer-funded takeover of Merrill Lynch will result in the firing of 35,000 people. The Fed replies with a new interest rate between 0.25 per cent and 0 per cent. Desperate times obviously call for desperate measures.

As further evidence that the disease which began with the CDO market and consumed the whole of global financial capital has spread to the real economy, where people actually produce things (as opposed to pushing paper around for ridiculous amounts of cash), President Bush declares that about $17.4 billion of the $700 facility will be diverted to America’s stricken car makers. Not many days pass before the Treasury announces that the finance arm of General Motors (which has become ever so ‘profitable’ during the derivatives’ reign) will be given $6 billion to save it from collapse.

By the year’s end, on 31 December, the New York stock exchange has lost more than 31 per cent of its total value when compared to 1 January of this cataclysmic year.

2009 - The never ending aftermath

January ~ Newly elected President Obama declares the US economy to be 'very sick’ and foreshadows renewed public spending to help it recover. As a stop-gap measure, his administration pumps another $20 billion into the Bank of America while watching in horror Citigroup split in two, a move intended to help it survive. US unemployment rises to more than 7 per cent and the labour market sheds more jobs

February - The Bank of England breaks all records when it reduces interest rates to 1 per cent (in its fifth cut since October). Soon after President Obama signs his $787 billion stimulus Geithner-Summers Plan1, which he describes as ‘the most sweeping recovery package in our history’. It is a pivotal moment to which we return in the main text below. Meanwhile, AIG continues to issue terrible news: a S61.7 billion loss during the last quarter of 2008. Its ‘reward7 is another $30 billion from the US Treasury.

March - The G20 group (which includes the G7, Russia, China, Brazil, India and other emerging nations) pledges to make ‘a sustained effort to pull the world economy out of recession’. In this context, the Fed decides that the time for piecemeal intervention has passed and says it will purchase another $1.2 trillion of ‘bad debts’ (i.e. of Wall Street’s now worthless private money).

April - The G20 meets in London, among large demonstrations, and agrees to make $1.1 trillion available to the global financial system, mainly through the auspices of the IMF, which soon after estimates that the Crash has wiped out about $4 trillion of the value of financial assets (warning that only one of these four trillions has been taken off the banks’ books, thus giving the impression that their bottom line is better than it truly is). In London, Chancellor Alistair Darling forecasts that Britain’s economy will decline by 3.5 per cent in 2009 and the budget deficit will reach £175 billion or more than 10 per cent of GDP.

May - Chrysler, the third largest US car maker, is forced by the government to go into receivership and most of its assets are transferred to Italian carmaker Fiat for a : song. The news from the financial sector continue to be bleak, as a government probe reveals that they are still in dire straits. The US Treasury organises another assistance package to the tune of more than $70 billion.

June - It is General Motors’ turn, America’s iconic car maker, to go bankrupt. Its creditors are forced to ‘consent’ to losing 90 per cent of their investments while the company is nationalised (with the government providing an additional $50 billion as working capital). GM’s own unions, who have become creditors owing to the company’s failure to cover its workers’ pension right, become part owners. Socialism, at least: on paper, seems alive and well and living in Detroit. Over the other side of the Atlantic Pond, the unemployment rate in Britain rises to 7.1 per cent with more than 2.2 million people on the scrapheap. Another indication of the state of the global economy is that in 2008 global oil consumption falls for the first time since 1993.

Note

1 Named after Tim Geithner, the new Secretary of the Treasury who previously served as Undersecretary to the Treasury when Larry Summers was Bill Clinton’s Secretary; and of course Larry Summers himself who is operating this time in his new capacity of Director of President Obama’s National Economic Council.

While it is beyond the scope of this book to present a complete history of the Crash of

2008, the above box relates all we need for our purposes - a catalogue of wholesale failure of the deregulated financial sector that spearheaded history’s greatest, deepest and most sustained intervention by the world’s governments. The astonishment that this story causes us every time we revisit its twists and turns can only be surpassed by the audacity of

what followed. In an effort to prove Marx’s hunch that capital knows no restraint, and before the dust had settled from the nuclear explosion it had caused, the financial sector embarked upon a new project: how to recreate its private money using as raw materials the public money the hapless taxpayer sent it in its hour of extreme need.

From June 2009 onwards, the financial press began reporting that banks were ready to return to the state the money that they borrowed (see Box 12.17 below). Most people thought that the banks, having received oceans of liquidity from the taxpayer, made amends, pulled their socks up, tided up their business, altered their ways, stopped meddling with toxic derivatives (CDOs, CDSs and the like) and started making money legitimately, from which they now wanted to repay the taxpayer - if only...

To see what really went on, it is important to take a closer look at the Geithner-Summen Plan; President Obama’s February 2009 own $1 trillion package for saving the banks from the worthless CDOs that were drowning them (see Box 12.16 above). The main problem the banks faced was that they were awash with the pre-2008 CDOs which no one wanted to buy at prices that would not cause the banks who owned them to declare that they were insolvent. Within these CDOs there were some solid mortgages, that homeowners continued to service and, of course, a lot of junk subprime mortgages too. What was their value? No one knew because (a) the CDOs were so complex that not even those who created them could work out their contents, and (b) the market in CDOs had perished and it was, therefore, impossible to price them by offering them for sale.

Tim Geithner’s and Larry Summer’s idea was simple: to set up, in partnership with hedge funds, pension funds, etc. a simulated market for the toxic CDOs, hoping that the new simulated market would start a trade going in existing CDOs that would restore enough value to them so that the banks could remove them from their liabilities column and start afresh. A sketch of their Plan follows.

Suppose bankB owns a CDO, let’s call it c, that B bought for $100, of which $40 was S’s own money and the remaining $60 was leverage (i.e. a sum that B somehow borrowed in order to purchase c). B's problem is that, after 2008, it cannot sell c for more than $30. The problem here is that, given that its vaults are full of such CDOs, if it sells each below $60, it will have to file for bankruptcy, as the sale will not even yield enough to pay its debt of $40 per CDO (i.e. a case of negative equity). Thus, B does nothing, holds on to c, and faces a slow death by a thousand cuts as investors, deterred by 5’s inability to rid itself of the toxic CDOs, dump B’s shares whose value in the stock exchange falls and falls and falls. Every penny the state throws at it to keep it alive, B hoards in desperation. Thus, the great bail out sums given to the banks never find their way to businesses that need loans to buy machinery or customers that want to finance the purchase of a new home.

The Geithner-Summers Plan proposed the creation of an account, let’s call it a, that could be used by some hedge or pension fund, call it H, to bid for c. The account a would amount to a total of, say $60 (the lowest amount that B will accept to sell c) as follows: the hedgefund H contributes $5 to a and so does the US Treasury. The $50 difference comes in the form of a loan from the Fed,41 The next step involves the hedge or pension fund, our H, to participate in a government organised auction for S’s c; an auction in which the highest bidder wins c.

By definition, the said auction must have a reservation price of no less than $60 (which is the minimum B must sell c for if it is to avoid bankruptcy). Suppose that H bids $60 and wins. Then B gets its $60 which it returns to its creditor (recall that B had borrowed $60 to buy c in the first place) and, while B loses its own equity in c, it lives to profit another day. As for hedge fund H, its payout depends on how much it can sell c for. Let’s look at two scenarios: a good and a bad one for H.

We begin with the good scenario. Hedge fund h discovers that, a few weeks after it purchased c for $60 (to which it only contributed $5), its value has risen to, say, S80, as the simulated market begins to take off and speculators join in. Of that $80, H owes $50 to the Fed and must share the remaining equity ($30) with its partner, the Treasury. This leaves H with $15. Not bad. A $5 investment became a $15 revenue. And if Hpurchases a million of these CDOs, its net gain will be a nice $10 million.

In the case of the bad scenario, //stands to lose its investment (the $5) but nothing beyond that. Suppose, for instance, that it can only sell CDO c, which it bought for $60 using account a, for $30 (which is what it traded for before this simulated market, created by the Qeithner-SummersPlan, came into being). Then, H will owe to the Fed more than it received. However, the loan by the Fed to H is what is known as a non-recourse loan; which means that the Fed has no way of getting its money back.

In short, if things work out well the fund managers stand to make a net gain of $ 10 from a $5 investment (a 200 per cent return) whereas if they do not they will only lose their initial $5. Thus, the Geithner-Summers Plan was portrayed as a brilliant scheme by which the government encouraged hedge and pension fund managers to take some risk in the context of a government designed and administered game that might work; one in which everyone wins -the banks (who will get rid of the hated CDOs), the hedge and pension funds that will make a cool 200 per cent rate of return, and the government, which will recoup its bail out money.

It all sounds impressive. Until one asks the question: what smart fund manager would spredict that the probability of the good scenario materialising is better than around lh?42 Who would think that there is more than one chance in three that they would be able to sell the said CDO for more than $60, given that now no one wants to touch the toxic CDO for more than $30? Who would participate in this simulated market? Committing one trillion dollars to a programme founded on pure, unsubstantiated optimism seems quite odd.

Were Tim Geithner and Larry Summers, two of the smartest people in the US administration, foolhardy? We think not. Their plan was brilliant but not for the stated purpose. It was a devilish plan for allowing the banks to get away with figurative murder. Here is our ¿interpretation of what really happened or, indeed, our answer to the question who would, in their right mind, participate in the Geithner-Summers simulated market? The hanks themselves!

Take bank B again. It is desperate to get CDO c out of its balance sheet. The Geithner-Summers Plan then comes along. Bank B immediately sets up its own hedgefund, H\ using some of the money that the Fed and the Treasury has already lent it to keep it afloat (see previous box for examples). H’ then partakes of the Plan, helps create a new account a ’, comprising $100 (of which H’ contributes S7, the Treasury chips in another S7 and the Fed loans $86) and then immediately bids $100 for its very own c. In this manner, it has rid itself of the $100 toxic CDO once and for all at a cost of only $7, which was itself a government handout!43

The significance of the subterfuge in the Geithner-Summers Plan goes well beyond its ethical or even fiscal implications. The Paulson Plan that preceded it was a crude but honest attempt to hand cash over to the banks no-questions-asked. In contrast, Geithner and Summers tried something different: to allow Wall Street to imagine that its cherished finan-cialisation could rise Phoenix-like from its ashes on the strength of a government-sanctioned plan for creating new derivatives. Come to think of it, the very essence of the Geithner-Summers Plan was the creation of synthetic financial products (account a in the example above) with which to refloat the defunct pre-2008 CDOs. Henceforth the government

Box 12.17 Recovery

(but only in Wall Street and the City of London)

June 2009 - A dozen US banks claim to have turned the comer and are now able to return a portion of the money they were lent in October 2008 (which is a tiny fraction of the total taxpayers’ outlay on saving them). Commentators note that this is a strategic ploy by bank management to pay themselves large bonuses. Goldman Sachs surprises with an unexpected announcement of an after-tax profit of $3.44 billion for the second quarter. At the same time, it announces that in the second quarter alone it has paid out $6.65 billion in pay and management bonuses. More banks announce large profit taking in the weeks that follow. Seasoned analysts, however, look on sceptically.

August 2009 - Barclays posts an 8 per cent rise in profits for the first six months of

2009, created mostly in its proprietary investment division (i.e., the department that continues to trade in derivatives and other such ‘products’).

Meanwhile, during the first two quarters of 2009, more American families lose their homes than ever before and whole neighbourhoods in California and the Midwest lay abandoned. Britain’s unemployment tally heads for the three million mark, Japan’s GDP falls by 14.2 per cent (in the first quarter of the year) and the OECD declares that the GDP of the 30 most developed countries will fall at an average rate of 4 per cent.

proceeded to organise a rigged auction for these CDOs in which hedge and pension funds would bid for them using the new, government sponsored, derivative-like money.

In short, the Obama administration blew a breezy wind into Wall Street sails by engineer-; ing a new marketplace for the old derivatives (which were replete with poor people’s mortgage debts) where the medium of exchange was a mixture of the old (refloated) derivatives and new ones (based not on poor people’s mortgages but on the taxes of those who could not avoid paying them; often the same poor people, that is). Thus, much of the banks; toxic assets were moved off their accounts.

Once the banks’ balance sheets were cleansed of most of the toxic CDOs, at a profit too, the banks used some of the proceeds, and some of the bail out money from the various waves of assistance received from the state, to pay the government back enough of the monies received in order to be allowed their hefty bonuses. In other words, the process of fashioning private money was on again after a short break of no more than a year.

In political terms, President Obama’s approval of the plan constitutes a complete capitulation to Wall Street. And as is usually the case with capitulations to sinister characters, no one thanked the capitulator. Indeed, the Geithner-Summers Plan increased the banks’ blackmailing power vis-à-vis the state. While President Obama’s administration was busily accepting the Wall Street mantra on no fully blown nationalisations (i.e. the dodgy argument that recapitalising banks by means of temporary nationalisations, as in Sweden in 1993, would quash the public’s confidence in the financial system, thus creating more instability which, in turn, might jeopardise any eventual recovery), the Street’s banks were already plotting against the administration, intent on using their renewed financial vigour to promote Obama’s political opponents (who offered them promises of offensively light regulation).

This twist took on added significance in January 2010 when the US Supreme Court, with a 5:4 vote, overturned the Tillman Act of 1907, which President Teddy Roosevelt had passed in a bid to ban corporations from using their cash to buy political influence. On that fateful Thursday the floodgates of Wall Street money were flung open as the Court ruled that the managers of a corporation can decide, without consulting with anyone, to write out a cheque to the politician that offers them the best deal, especially regarding regulation of the financial sector in the aftermath of 2008.

President Obama’s reaction to this ‘betrayal’ was to use his anger smartly. He empowered Paul Volcker, who was still going strong in his eighties, to author the regulatory legislation under which Wall Street will have to labour in the future; and to write it in such a manner as to tighten the authorities’ grip over Wall Street in important ways. Volcker, in his new capacity as head of the Economic Recovery Advisory Board (ERAB), came up with the Volcker Ride which the administration seems, at the time of writing, determined to push through Congress. The Volcker Rule revives the New Dealers’ Glass-Steagall Act, which Larry Summers had done away with in the 1990s. It prohibits banks from doubling in derivatives and other exotic financial products. Volcker’s basic idea is that banks that accept deposits and are insured against failure by the state ought not to be allowed to participate in either the stock market or the derivatives’ trade.

Having to face one of the Global Minotaur's early prophets and minder during its 1980s adolescence (recall Volcker’s role from Chapter 11), has given Wall Street bankers a few sleepless nights. However, it would be foolhardy to bet against the Street’s capacity to overcome any regulatory constraints it finds in its way; especially after having recovered from its near-death 2008 experience.

So far, the above account of the Crash moved within the smoke and mirrors of Wall Street and its hazardous games. Let us conclude this section with some hints regarding the ¿real : costs of the Crash as experienced by real people whose job involves hard work but no gambling with other people’s money.

Figure 12.8 uncovers the true cost in units of anguish that the Crash of2008 visited upon the long-suffering American working class. After three decades of living in the Global Minotaur's world, with real wages that never rose above their early 1970s levels, of working

Figure 12.8 US job losses (in thousands) during the 12-month period around the worst post-1945 recessions.

more and more hours and achieving remarkable productivity levels for no tangible benefits, suddenly they were literally turned into the streets in their millions. Almost four million Americans lost their jobs while, according to the US Mortgage Bankers Association, it is estimated that 1 in 200 homes was repossessed by the banks. Every three months, from 2008 to 2010, 250,000 new families had to pack up and leave their homes in shame. On average one child in every US classroom was at risk of losing his or her family home because the parents could not afford to meet their mortgage repayments.

In the aftermath of 2008, American families are growing more desperate at the time of Wall Street’s celebrated tax-fuelled recovery. According to the US-based Homeomiership Preservation Foundation, which surveyed 60 thousand homeowners, more than 40 per cent of American households are getting further and further into debt every year. Sometimes the most insightful data come from unexpected sources. Figure 12.9 plots the average height of US office buildings against time. It is uncanny how the plot picks up all the troughs and peaks of the economic cycles. The Crash oj 2008 comes across this graph as a true successor to the calamity that was 1929.

Beyond the United States, it is often said that the Developing World was relatively unscathed by the Crash of 2008. While it is true that China successfully used simple: Keynesian methods for delaying the crisis through spending more than $350 billion on infrastructural works in one year (and close to twice that by 2010), a study by Beijing University: shows that poverty rates actually increased while the rate of private expenditure fell (with : public investment accounting for the continuing growth). Whether this type of Keynesian; growth is sustainable without the Global Minotaur remains to be seen.

Countries like Brazil and Argentina, which as we have seen export large quantities of primary commodities to China, weathered 2008 better than others. India too seems to have managed to generate sufficient domestic demand. Nevertheless, it would be remiss not to take into consideration the fact that the Developing World had been in deep crisis, caused by-escalating food prices, for at least a year before the Crash of 2008. Between 2006 and?; 2008 average world prices for rice rose by 217 per cent, wheat by 136 per cent, corn by

Figure 12.9 The recession of ambition.

Source: The Netherlands Architects Association Annual Report 2010.

125 per cent and soybeans by 107 per cent. The causes were multiple but also intertwined with the Global Minotaur.

Financialisation, and the ballistic rise of options, derivatives, securitisation, etc. led to new ways of speculation at the Chicago Futures’ Exchange over food output. In fact, a brisk trade in CDOs, comprising not mortgages but the future price of wheat, rice and soybeans, gathered steam in the run up to 2008. The rise in demand for bio-fuels played a role too, as they displaced normal crops with crops whose harvest would end up in 4x4 monsters loiter-ins around Los Angeles and London.

Add to that the drive by US multinationals like Cargill and Monsanto to commodify seeds in India and elsewhere, the thousands of suicides of Indian fanners caught in these multinationals’ poisonous webs and the effects of the demise of social services at the behest of the IMF on its special adjustment programmes (SAPs), etc., and a fuller picture emerges. In that picture, the Crash of2008 seems to have made a terrible situation (for the vast majority of people) far worse.44 Tellingly, when the G20 met in London in April 2009, and decided to bolster the IMF’s fimd by $1,1 trillion, the stated purpose was to assist economies worldwide to cope with the Crash. But those who looked more closely saw, in the fine print, a specific clause; the monies would be used exclusively to assist the global financial sector. Indian farmers on the verge of suicide need not apply. Nor should capitalists interested in investing in the real economy.

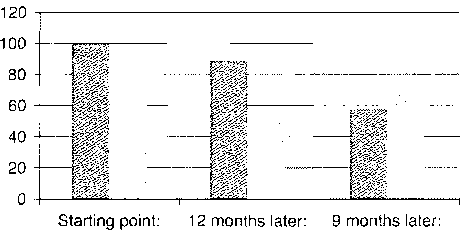

Glancing at the world in its totality, it is hard to miss the significance of 2008. Figure 12.10 offers a useful comparison of the Crash of2008 with the Crash of 1929. Based on the assumption that the two calamities began in June 1929 and April 2008, it normalises data so that both the 1929 and the 2008 numbers are arbitrarily set equal to 100 for the relevant starting point of each Crash (June 1929 and April 2008 respectively). The first graph concerns world output, the second graph looks at the total value of shares in all the stock exchanges of the world (global equities) and the third graph plots the total volume of global trade (measured in discounted dollars).

One thing becomes apparent. By all three measures, the Crash of2008 was significantly worse during the first year. In the second year, recovery has been stronger. This is clearly due to the large stimulus packages (quite separately from the injections of money into the banks) that governments unleashed onto world capitalism in a gallant attempt to save it from itself. However, it is also clear that the recovery is a relative one. The world is still producing less than in 2007 even though China, India, Brazil and a number of other countries have been growing quite well. When we take into consideration the distributional aspects involved, it is not hard to see that the Crash of2008 is having devastating effects on those at the sharp end worldwide.

Moreover, two menacing dark clouds are hanging over the world economy. First, there is the question that the Greek crisis posed in 2010 (see next section for more). Now that public money has replaced the burnt out private money of Wall Street, and the public debt of various governments has risen sharply, should we anticipate a new Credit Crunch or even a new financial storm to spring out in the market for government debt? Second, what will we do without the Global Minotaur? After all, that callous beast kept up the aggregate demand of the surplus nations (Germany, Japan and China). Now that the beast is wounded by the Crash of2008, and US trade deficits are not the vacuum cleaners (sucking in mountainous imports) that they used to be, what will play its role?

There is no better place to start looking into these questions than in Europe’s heartland. The next section takes us there, to the axis linking Berlin, Frankfurt and Brussels with Athens, Lisbon, Rome and Madrid.

World output/income during the crash of 1929

World output/income during {he crash of 2008

WÊÊ0

■

■

ÉÊÊi

mm

9 months later: April 1930, Feb 2010

Starting point: June 1929, April 2008

12 months later: June 1930, April 2009

B Global equities during the crash of 1929

K Global equities during the : crash of 2008

June 1929, April 2008

June 1930, April 2009

April 1930, Feb 2010

Global trade during the crash of 1929

Global trade during the crash of 2008

Starting point: 12 months later: 9 months later: June 1929, April June 1930, April April 1930, Feb

2008 2009 2010

Figure 12.10 A comparison of the Crash of 1929 with the Crash of'2008.x

Note: See Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke (2010) ‘What do the new data tell us’, mimeo. March

12.6 First as history then as farce: Europe’s crisis in context

Saving the banks - European style

The demise of the Global Plan in the 1970s had dealt a powerful blow at Europe. Somehow, Europe managed to recover by adapting to the new regime, the Global Minotaur. It learned the art of nourishing the transatlantic fiend with steady capital flows in return for a healthy trade surplus, particularly in manufactures.45 At the same time, its own financial sector, especially the French and German banks (not to mention, of course, the City of London which was closer to Wall Street than New Jersey), jumped on the financialisation gravy train from which it too drew substantial benefits (see Section 12.4).

When the Crash of 2008 hit, and the Global Minotaur was seriously wounded, Europe was destabilised. On the one hand, it had lost a critical source of aggregate demand while, at once, its banks faced meltdown as the American CDOs bursting out of its vaults, turned to ash. Despite European gloating that this was an Anglo-Celtic crisis, and that its own banks had not been taken over by financialisation’s equivalent to a gold fever, the truth soon came out.

When the crisis struck, German banks were found out: for they had, secretly, reached an average leverage ratio (i.e. the ratio of money borrowed for the purpose of speculation to own money used) of 52 to 1; a ratio much higher than the already exorbitant ratio common in Wall Street and London’s City. Even the most conservative and stolid state banks, the Landesbanken, ‘proved bottomless pits for the German taxpayer’, once the CDO market collapsed.46 Similarly in France; from 2007 to 2010 French banks had to admit that they had at least €33 billion invested in CDOs that are, post-2008, worth next to nothing.47

Additionally, the Bank for International Settlements (the body representing the world’s central banks) recently disclosed that European banks are terribly exposed to the debts of precarious economies from Eastern Europe and Latin America, not to mention around €70 billion of bad Icelandic debts. Austria’s exposure to so-called ‘emerging markets’ amounts to 85 per cent of the Alpine country’s GDP, and most of it is owed by countries about to melt down {e.g. Hungary, Ukraine and Serbia). Spanish banks, in particular, lent $316 billion to Latin America, almost twice the lending by all US banks combined (S172 billion).

The European Central Bank (ECB), the European Commission (the EU’s effective ‘government’) and the member states rushed in to do for the European banks that which the US administration had done for Wall Street. They shoved in the banks’ direction quantities of public money the size of the Alps, so as to replace the ‘departed’ private money with fresh public money borrowed by the member states. So far, this seems identical to the US experience; only there were two profound differences.

The first difference is that the Euro is nothing like the Dollar, as Chapter 11 made clear. While the Dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, the Fed and the US Treasury can write blank cheques knowing that it will make very little difference on the value of the dollar, at least in the medium term. Indeed, IMF data show that the dollar’s share of global reserves.was 62 per cent at the end of 2009 and has, since then, been rising in response to Europe’s post-2010 sovereign debt crisis (see below).

The second difference concerns the way that European banks succeeded in emulating Wall Street by using the post-2008 infusion of public money in order to start a new process of ‘minting’ fresh private money. As the previous section showed, Wall Street did this by utilising the Geithner-Summers Plan which, with the connivance of the US government, created from scratch a new type of financial instrument that allowed LIS banks to shift the toxic CDOs from their balance sheets at the taxpayers’ expense. The European banks did the same; only without the direct cooperation, or even knowledge, of the state (either of nationstates or of the EU). This is how they did it.

Between 2008 and 2009, as mentioned above, the ECB, the European Commission and the EU member states socialised the banks’ losses and turned them into public debt. Meanwhile, the economy of Europe went into recession, as expected. In one year (2008-9) Germany’s GDP fell by 5 per cent, France’s by 2.6 per cent, Holland’s by 4 per cent, Sweden’s by 5.2 per cent, Ireland’s by 7.1 per cent, Finland’s by 7.8 per cent, Denmark’s by 4.9 per cent, Spain’s by 3.5 per cent. Suddenly, hedgefunds and banks alike had an epiphany: why not use some of the public money they were given to bet that, sooner or later the strain on public finances (caused by the recession on the one hand, which depressed the governments’ tax take, and the huge increase in public debt on the other, for which they were themselves responsible) would cause one or more of the Eurozone’s states to default?

The more they thought that thought, the gladder they became. The fact that Euro membership prevented the most heavily indebted countries (Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Ireland Belgium) from devaluing their currencies, thus feeling more the brunt of the combination of debt and recession, focused their sights upon these countries. So, they decided to start betting, small amounts initially, that the weakest link in that chain, Greece, would default As London’s famous bookmakers could not handle multi-billion bets, they turned to the trusted CDSs; insurance policies that pay out pre-specified amounts of money if someone else defaults.

The reader will notice the subtle but important difference from the pre-2008 US-centred CDOs: whereas the latter constituted a bet that homeowners would pay back their debts, the EU-centred CDSs of the post-2008 era were naked bets that some EU state would not be able to pay its bets back. Soon, the issuers of these CDSs discovered, with glee, that their new ‘products’ sold like hot cakes. They had emerged as the new private money of the post-2008 world!

Of course, the greater the volume of trade in this newfangled private money the more the capital was siphoned off both from corporations seeking loans to invest in piudui.Liu-activities and from states trying to refinance their burgeoning debt.

In short, the European variant of the banks’ bail out gave the financial sector the opportunity to mint private money all over again. Once more, just like the private money created by Wall Street before 2008 was unsustainable and bound to turn into thin ash, the onward march of the new private money was to lead, with mathematical precision, to another meltdown. This time it was the sovereign debt crisis, whose first stirrings occurred at the beginning of

2010 in Athens, Greece.

Greeks bearing debts

In October 2009, the freshly elected socialist government announced that Greece'' mu-deficit was in excess of 12 per cent (rather that the projected 6.5 per cent, already more th;m double the Maastricht limit). Almost immediately the CDSs predicated upon a Greek doiaul: grew in volume and price, thus pushing the interest rate the Greek state had to pa\ to borrow in order to refinance its €300 billion debt (more than 100 per cent of GDP) above 4,5 per cent (when, at the same time, Germany could borrow at less than 3 per cent). By January 2010 it had become clear that the Greek government would be in trouble meeting its repayments during the next 12 months. The task it was facing was indeed herculean: to pay back maturing bonds to the tune of more than €60 billion and borrow more to finance a large annual budget deficit; and all this in the midst of a recession that depleted its effective tax base.

Informally, the Greek government sought the assistance of the EU. What it asked for wa* not cash as such but some form of statement on the part of the EU or the ECB that Greece s Eurozone partners would stand behind any new loans that Greece took out. Such a guarantee, if issued in January or February 2010, would have ensured that Greece would borrow a-, manageable interest rates and might, therefore, avoid both defaults without having to go to Europe cap in hand for real money. However, this request was turned down by ('hanceiio.

Angela Merkel who issued her famous nein-cubed: nein to a bail out for Greece; nein for interest rate relief; nein to the prospect of a Greek default.

The triple no was unique in the history of public or even private finance. Imagine if Secretary Paulson had said to Lehman Brothers, in October 2008, the following: ‘no, I am not soing to bail you out’ (which he did say); ‘no, I shall not organise for you low interest rate loans’ (which he may have said, but to no avail); and ‘no, you cannot file for bankruptcy' (which he would never have said). The last ‘no7 is unthinkable. And yet this is precisely what the Greek government was told. Mrs Merkel could fathom neither the idea of assisting Greece nor the idea that Greece would default on so much debt held by the French and German banks (about €75 billion and €53 billion respectively).

The result was that from January to April 2010 Greece continued to borrow at increasing interest rates, sinking deeper and deeper into the mire, while new CDSs were issued placing increasing bets on a Greek default and netting the banks indecently large profits. On 11 April, and after a major altercation with President Sarkozy of France, Mrs Merkel relents and announces a joint venture with the IMF for ‘rescuing’ Greece. According to that plan, the Eurozone (EZ) and the ECB would offer €30 billion, the IMF would chip in another €15, and Greece would have to accept draconian austerity measures to qualify for the loans.

While the Greek government sighed with relief, the financial markets did not take long to decide that, despite the IMF-EZ-ECB package, it was still worth betting on a Greek default. They were right: Greece had to find a lot more money than there was on the table; the offered interest rates were shockingly high;4* and the austerity policies to be introduced were so savage that the Greek economy would go into a tail-spin once they were introduced.

Soon after, and especially when Mrs Merkel appeared reluctant to commit even to this package (before a key state election in Germany was out of the way), the hedgefimds and the banks decided it was time to bet even more on a Greek default, to churn out a lot more such CDSs. In short order, the Greek government saw the interest rate, that the money markets were demanding in order to lend it cash, skyrocket to above 12 per cent. It immediately declared that it was withdrawing from the money markets and that it would request loans from the announced (but not finalised) IMF-EZ-ECB package.

By itself, the Greek government’s request would not have swayed Germany. Mrs Merkel seemed prepared to let Greece twist in the wind until the very last moment, when it would have to step in in order to prevent the Eurozone’s first default. That moment came in early May of 2010. Under pressure from France and the ECB, Germany succumbed not only to validating the original IMF-EZ-ECB package but, astonishingly, to boosting its size from €35 billion to €110 billion for Greece alone. Nevertheless, even that was not enough to avert the gathering storm clouds.

Within days, the world’s financial system went into something close to the Credit Crunch pt 2008. Starting with the market for government bonds, which at least in Europe seized up completely, the world’s stock exchanges began to tumble. Hedge funds and banks continued betting against not only Greek debt but against an assortment of European state debts. So, four days after the €110 billion IMF-EZ-ECB package had been announced, a new startling announcement was made: (a) the IMF-EZ-ECB package would rise to €750 billion (€500 kv the EZ-ECB and €250 by the IMF) and extend to all eurozone deficit countries; and (b) the ECB would start buying (second-hand) member state bonds (i.e. debt).

Thus, the Euro area changed overnight. The strict separation of monetary policy (the ECB s remit) from fiscal policy (that was left to member states, under the Maastricht conditions) ended the moment the whole of the Eurozone (in association with the IMF) were made responsible for bailing each other out and, more importantly, by having the ECB cross into the area of debt management. These two moves tore up the Maastricht treaty without however, putting some other, rational, architecture in its place. Instead, following those momentous developments, the only discussion in Brussels on institutional reform concerns a further tightening of budgets across Europe; even on instilling a legal obligation to run balanced budgets in the constitutions of member states.

The banks and the hedge funds responded, first, by easing their bets on Greece, once a Greek default was delayed by at least two years. However, they looked closely at the figures and realised that the pledged $750 billion of the IMF-EZ-ECB mechanism would not solve the problem. For the austerity package that went along with it was more likely than not to exacerbate the recession, especially in the deficit countries, lessen their tax take and spearhead another debt crisis further down the road. Would the surplus countries be able to put together another loan package in two years’ time, before their own bonds got attacked by the infamous CDSs?

Thus, shortly afterwards, the speculators took their eyes off Greece and began to issue new CDSs, no longer based on a Greek default but, this time, on a falling and faltering Euro. Thus, private money continues to grow by draining the life out of the very public purses that sustained it. Incredibly, this growth spurt at the expense of the Eurozone was massively assisted by the IMF-EZ-ECB package itself. The reason is that the €440 pledged by the Eurozone to the IMF-EZ-ECB loan package would come in the form of a euphemistically named Special Purpose Vehicle; if this sounds like a Special Investment Vehicle (which, before 2008 were the outfits the banks created to issue derivatives, like the CDOs) it is because it is one. Box 12.18 explains.

Box 12,18 A European Geithner-Summers Plan for bailing out Europe’s banks

In May 2010 the EU created a so-called Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) whose aim will be, purportedly, to help deficit Eurozone countries, such as Greece, Spain, etc., avoid defaulting on its debts in case the money markets refuse to lend them more:at manageable interest rates (as was the case with Greece in April-May of 2010). Many commentators celebrated this turn of events as the beginning of a European Monetary Fund, a first step in the post-Maastricht era and down the path that leads to genuine economic integration.

The SPV will take the form of a company called the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and will begin life with a capital base of €60 billion made available from the EU’s own budget and €250 from the IMF. Additionally, it will be able to borrow up to €440 billion from the financial markets and institutions. Unlike the IMF-EZ-ECB package for Greece, which is based on bilateral parliament-sanctioned agreements between Greece and all other EZ countries, the EFSF will lend at the behest of the EZ governing group, the so-called Eurogroup. This will speed up its capacity to intervene without the added uncertainty and delay of 16 separate parliamentary debates.

So far so good. While the EFSF does not address the root causes of the crisis, at least it seems like a decent response to its symptoms. Until, that is, one scratches the surface of the €440 billion part of the fund which the EFSF is meant to raise on

I the markets. Conventional wisdom tells us that the trick to the EFSF’s potential suc-I cess is that it borrows by issuing its own bonds (let’s call them EFSF bonds) which are I supported by collateral provided by all the EZ countries in proportion to the size of | their economy. In other words, Germany and France put up most of the collateral. This j should encourage investors to buy the EFSF bonds at low interest rates, j The problem, and worry, here is that this bears an uncanny similarity with the cir-| cumstances that gave rise to the dodgy CDOs in the United States and, later, their i European counterparts. Looking back to the US-issued mortgage-backed CDOs, we

I find that the trick there was to bundle together prime and subprime mortgages in the ! same CDO, and to do it in such a complicated manner that the whole thing looks like a sterling investment to potential buyers. Something very similar had occurred in Europe after the creation of the Euro: CDOs were created that contained German, Dutch, Greek, Portuguese bonds, etc. (i.e. debt), in such complex configurations, that investors found it impossible to work out their true long-term value. The tidal wave of private money created on both sides of the Atlantic, on the basis of these two types of CDOs, was the root cause, as we have seen, of the Crash of2008.

Seen through this prism, the EFSF’s brief begins to look worrisome. Its ‘bonds’ will be bundling together different kinds of collateral (i.e. guarantees offered by each individual state) in ways that, at least till now, remain woefully opaque. This is precisely how the CDOs came to life prior to 2008. Banks and hedgefunds will grasp with both hands the opportunity to turn this opacity into another betting spree, complete with CDSs taking out bets against the EFSF’s bonds, etc. In the end, either the EFSF bonds will flop, if banks and hedge funds stay clear of them, or they will sell well thus occasioning a third round of unsustainable private money generation. When that private money turns to ashes too, as it certainly will, what next for Europe?

Just as the Geithner—Summers Plan of 2009 sought to solve the problem with the toxic derivatives by issuing new state-sponsored derivatives (recall the previous section), so too the IMF-EZ-ECB package (see Box 12.18) creates new derivative-like bonds that will be sold to the banks and hedge funds in return for money that will be passed on to member states which will then be returned to the banks (that hold the member states’ debt) which are already profiting from issuing their own derivatives (the CDSs) whose value depends on the member states (separately or together, as the entire Eurozone) fail use...

Is it any wonder that in 2010 Europe entered a crisis from which it seems incapable of escaping? Which bring us to the main question: does Germany’s leadership not see this? Why is the Eurozone reacting so sluggishly and so weakly to the challenge? Why have they failed to take the crisis’ measure?

The conventional answer is that Europe suffers from a simple coordination failure. Too many cooks spoiling the broth; too many small countries that insist on holding on dearly to their small country mentality and, therefore, failing to create a Europe with a mentality fit for its size and proper role. Though there is some truth in this, with sixteen different fiscal policies, no centralised supervision and lowest common denominator leaders, it is not the reason. The reason is different and has to do with the analysis in Section 12.4.

A New Versailles

Section 12.4 argued that the formation of the Euro crystallised a situation that had emerged since the rise of the Global Minotaur in the 1970s and enabled Germany to reach unprecedented surpluses in a context of deepening European stagnation. Figuratively, we labelled the German economy, with its heavy reliance on both the United States and the rest of Europe as sources of aggregate demand for its industrial output, the Minotaur’s Simulacrum.

The Crash of2008 shook both pillars of Germany’s successful strategy for living happily within the Eurozone. The United States drastically reduced its imports and the German banks fell to the ground. The Simulacrum was on skid row. Profoundly worried about this unexpected twin blow, Germany’s leadership hardened its neo-mercantilist stance and unilaterally decided to rewrite the rules of the game.

Following the events of May 2010, and the creation of the IMF-EZ-ECB mechanism, plus the ECB’s new role in the bond market, many commentators heralded these developments as a step towards a new Rational Plan for Europe; one that brings the Eurozone area closer to federalism (at least at the level of Economic policy). So far, it is nothing of the sort, Germany seems hell bent on forcing the Eurozone members to embark upon a series of competitive austerity drives. Having ‘won’ such a game in the 1990s (see Section 12.4, and in particular the subsection on German reunification), Mrs Merkel wants to play the same game and by the same German rules. This is why no one is even allowed to discuss alternative policies for handling Europe’s debt crisis in its entirety, that is, tackling at once the twin problems of (a) its indebted member states and (b) its banking system (which is, once again, hooked on unsustainable private money).

Box 72.19 A modest proposal for Europe

Each and every response by the Eurozone (EZ) to the galloping sovereign debt crisis that erupted at the beginning of 2010 has consistently failed to arrest the fall. This includes the quite remarkable formation of a €750 billion IMF-EZ-ECB Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) for shoring up the fiscally challenged Eurozone members. The reason is simple: the EZ is facing an escalating twin crisis but only sees one of its two manifestations. On the one hand we have the sovereign debt crisis that permeates the public sector in the majority of its member countries (France and the countries we called ‘magpies’ in Section 12.4). On the other hand we have Europe’s private sector banks many of whom find themselves on the brink. Yet, the EZ remains in denial, pretending that this is solely a sovereign debt crisis that will go away as long as everyone tightens their belt.

The €750 billion SPV has failed to convince that it will, in itself, stave off defaults. | The reason is that it offers no comprehensive solution to an all-embracing problem, j For instance, it was agreed that the Greek state will be lent up to €110 billion over j three years to help it deal with its €330 billion debt, which it owes mainly to European j banks that are, themselves, facing a serious challenge to their continued existence, j While the banks themselves borrow from the ECB at less than 1 per cent interest rate, j Greece borrows from the SPV at close to 5 per cent to pay back the banks at an interest j rate well in excess of 6 per cent. All this, against the background of a shrinking national j income (Greek GDP will shrink by 5 per cent in 2010) and with a commitment to undertake fiscal tightening measures that will accelerate further the loss of national income and, thus, constraining Greece’s tax base further. Naturally neither the mar-Î kets nor the banks trust that Greece will be able to repay its loans (the old as well as the new ones it is currently borrowing from the SPV), especially after the SPV is wound down in 2013 (if everyone goes to plan). Thus, the CDSs on a future Greek default divide and multiply.

This is a textbook case of how not to run a ‘bail out’. Is it a puzzle that few really believe in the SPV’s chances of solving the Eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis? How could the SPV be organised differently? Is there an alternative? The question grows in pertinence now that the SPV will be extended to other countries such as Portugal, Spain, etc. An outline of a modest proposal for an alternative SPV, let’s call it SM (support mechanism) is offered below.