400—--

240

2000 2003 2007 2009

Figure 12.12 Increase in US assets (in S billion) OWNED by foreign state institutions.

The result of all this inability to come to terms with a simple truth, namely that forcing the deficit countries to deflate was a plague on the house of the (until then) surplus countries, translating into wholesale poverty for everyone and a real war that humanity has since been trying to put behind it. In Keynes’ words:

the insincere acceptance... of impossible conditions which it was not intended to carry out [made] Germany almost as guilty to accept what she could not fulfil as the Allies to impose what they were not entitled to exact.50

If Versailles teaches us anything it is that the strong do not always impose upon the defeated a treaty that is in its own interests. Sometimes they get carried away by their urge to punish, flex their muscles a little too energetically and in so doing end up punishing themselves. This is how we see the conditions imposed upon the Eurozone’s deficit countries that will be forced to resort to the IMF-EZ-ECB €750 billion loan package from the new SPV formed in the context of the 2010 sovereign debt crisis.

This is what Keynes wrote on the consequences of the Versailles Treaty:

Moved by insane delusion and reckless self-regard, the Greek people overturned the foundations on which we all lived and built. But the spokesmen of the European Union have run the risk of completing the ruin, which Greece began, by & financial assistance package which, if it is carried into effect, must impair yet further, when it might have restored, the delicate, complicated organisation, already shaken and broken by the 2008 crisis, through which alone the European peoples can employ themselves and live.51

These are, of course, not exactly Keynes’ words. But they are not far off! All we did was to replace some of his words with the ones appearing in bold above. Indeed, Keynes might have just as well have been writing about the Greek fiscal calamity and the IMF-EZ-ECB package that was, effectively, imposed upon the bankrupt Greek state and subsequently extended to the rest of Europe’s magpies.

Summing up, the IMF-EZ-ECB package is a most peculiar sort of punishment. Indeed, it is an irrational sentence both because

(a) it constitutes a cruel and unusual punishment52 and

(b) it is bound to hurt the punishers disproportionately more compared to a fairer punishment for Greece.53 Ironically, from this perspective, it is not very dissimilar to the original Versailles Treatyl

Whither Europe?54

• Quidquid id est, timeo Dañaos et dona ferentes (Or in a popular German rendering: Vorsicht vorfalschen Freunden)55

• The problem, as always, was what to do with Germany56

The Germans are right to think that Greece is a problem for the Euro. But, at the same time, Germany is an equally large problem for the common currency. In a sense, Greece and Germany are two sides of the same problematic coin.

History is something which all countries have but some have more than others. The Greeks have too much of it; but the Germans make up for their history’s relative brevity with a great deal of historical gravitas. While one can easily imagine a European Union without

Greece, one without Germany is unimaginable. Having said that, Germany would never have become as central to Europe if it were not for the minnows (plus France) that kept its industries in business during the crucial years of the Global Plan. Even during the Global Minotaur's reign, the magpies provided German capital with surpluses which assisted it areatly in globalising and thus improving its position relative to both the Minotaur and the praçon (NB the Chinese hunger for German capital goods).

The Maastricht Treaty was not a treaty imposed by the bankers, as many on the European left had claimed. It was more than that: a charter for the German dominance of the Eurozone; a monetary manifestation of the Minotaur’s Simulacrum. Locked into the single currency and the fiscal rules of Maastricht, and with the German real wage controlled by the country’s functioning corporatist institutions,57 the Euro area was the new Imperial Preference Area for German dominance.

Since 2008, the ECB and the Eurozone’s ant-based leadership have put all their energies into serving a two-item agenda. First item on the agenda was, as in the United States, the salvation of the banking system. Thus, they risked transferring all of the latter’s sins onto the public accounts. Second item on the agenda was the preservation of the spirit of Maastricht, an imperative that had nothing whatsoever to do with the stated purpose of keeping the lid on inflation and everything to do with the paramount task of preserving the status quo, according to which the ants grow by expanding their trade surpluses while the magpies are forced into whatever fiscal posture is necessary to manage their debt levels.

The reasons why this kind of Europe is currently unravelling is not at all a mystery. For the two-item agenda above became unsustainable once the Global Minotaur, severely injured by 2008, lost its appetite for the ants’ exports and the Chinese Dragon turned inward.58 In short, the Eurozone of 2000-08 is not viable post-2008. The former could soldier on, despite the imbalances between the deficits and surplus countries, as long as the Eurozone enjoys a large trade surplus with the rest of the world. But when the United States and China dried up as a source of excess demand for European manufactures, the ants had to rely more and more on the magpies for their surpluses. Doing so while immediately insisting that the magpies rein their deficits in defied logic. The financial markets got a whiff of that incongruity and started issuing new piles of private money, in the form of CDSs betting against Greece, Portugal, Spain, the Euro itself.

Back in 1944, the New Dealers faced the very same problem: the United States was facing a future in which it would have to occupy a surplus position vis-à-vis the rest of the world and it was a matter of concern that the aggregate demand for its exports should come from somewhere and not be undermined either by competitive currency devaluations or by competitive wage deflation. The Global Plan (i.e. Bretton Woods, the Marshall Plan and all the interventions during the 1944-71 period discussed in Chapter 11) was meant to address this concern. It did so for a decade before the Plan began to unravel and then, in August 1971, die. The reason, as we saw, was that the hegemon behind it went into deficit too quickly and had to react somehow to retain its hegemony; the Global Minotaur being the outcome.

The creation of the Euro, and the Maastricht Treaty underpinning it, were not a manifestation of the continent’s esprit communautaire, as Europeans like to think, but rather a negation of both the supranational and the communitarian ideological principle. It was an instance of power imposing a dogma.59 The fact that Germany’s leaders seem unable to reconcile with is that that power withered the moment the Global Minotaur, upon which it was predicated, fell seriously ill. If they continue to live in denial, the project of European integration will surely wither too.

So what? Let Europe wither, we hear some Germans say. The problem, however, is that Germany is not doing that either! On the one hand, it blocks any serious debate on rationalising the Eurozone, in fear of losing its surpluses, and, on the other, it does not even come out and courageously declare the whole thing a bad idea with a proposal to dismantle the Euro Instead, it keeps countries like Greece in intensive care, administering enough medicine to keep it going but not enough to help it recover.

In effect, the ants of Europe are turning the magpies’ terrains into sun-drenched wastelands (except for Ireland, which will return to its pre-tiger sodden, mulchy past) and are consequently, pushing the whole deficit area of the Eurozone into an accelerating debt-deflationary downward spiral. But this is a most efficient way of undermining Germany’s own economy in the post-2008 world. Assuming, for argument’s sake, that Greece is getting its just deserts, do the hard-working German workers deserve a political elite that quick" marches them straight into economic catastrophe?

We believe not. But it has happened before and it may happen again unless Germany grasps, as the United States did in 1947, the subtle difference between authoritarianism and hegemony. To quote Keynes’ 1920 book on the Versailles Treaty one last time:

Perhaps it is historically true that no order of society ever perishes save by its own hand.60

12.7 A (Chinese) future for the beast?

We closed Chapter 11 with Paul Volcker’s dictum, circa 1979, that US hegemony required the disintegration of the global economic order. Volcker was summing up the end of the Global Plan which begot the Global Minotaur, a beast that drew its primal energy from the crisis in the real economy (spearheaded by the US-sponsored oil crisis of the 1970s that Volcker had a small part in designing) and served the purpose of allowing the US middle and upper classes to live, quite sustainably, beyond their means for three whole decades.

The 1970s crisis, which was overcome as late as in the mid-1980s, threatened capitalism’s monetary system (through the unpredictable escalation of inflation) and quickly spread from the real economy into the world of finance, Volcker, as the Fed’s Chairman during the crucial 1979-87 period, ruthlessly increased interest rates in order to quash inflation and transfer capital from the rest of the world into the United States. Once the flow of other people’s goods and capital into the United States started in earnest, the Fed eased interest rates substantially. To that effect it was helped significantly by Asia and, in particular, the South-East Asian crisis of 1998.

What happened in 1998 was a nightmare for South-East Asia’s and Argentina’s people. However, the crisis, while reflected in similar meltdowns in Mexico and Russia, did not manage to contaminate Wall Street, the City of London or the EU, although the IMF’s heavy-handed intervention, with its stringent, inhuman austerity that it imposed on these countries (in return for loans of dubious benefit to the average citizen), left an indelible mark on Asia’s and Latin America’s consciousness: ‘never again!’, they screamed inside their heads. Never again will we find ourselves in a state of dependence on the IMF and the rest of the West’s institutions.

The result was a rise in the rate at which Asian savings were sent to Wall Street to buy assets that would act as a buffer in case of another crisis.61 This flood of capital into Wall Street (in addition to the influx of cany trade into New York, Europe and London caused by zero per cent Japanese interest rates) pushed US interest rates down and kept them there for a very long while. We have already seen how this process depressed US interest rates, Strengthened the Minotaur and reinforced financialisation.

In 2008 when that bubble burst and a crisis that began in the murky world of real estate and finance spread to the real economy, the United States responded robustly with unheard of spending programmes (which Keynes, one imagines, would have approved without necessarily thinking of as sufficient). Europe, in contrast, found itself in a bind and followed only reluctantly. Not only had its Eurozone architecture never contained a Plan A (let alone a Plan B) in case of a crisis, largely due to the success of neoclassical economists (the Econobubble, as we call it) in convincing policymakers in Brussels (as they had done elsewhere) that crises were obsolete, but its currency, the Euro, lacked reserve currency status as well.62

So, while the US administration (of both political persuasions) felt at liberty effectively to throw trillions of dollars (that it never actually owned) at the crisis, the Europeans were loath to follow suit. Organising such bold steps via a consensus of 16 parochial administrations was tough going, especially in view of their division between the ants, the magpies and, somewhere in the middle, France. Thus a crisis which had begun in the United States threatened to bring down the Eurozone; echoes of Treasury Secretary John Connally’s infamous 1971 message to the Europeans: ‘it is our currency but it is your problem.’ All that Tim Geithner, the current US Treasury Secretary, needs to do when addressing today’s European leadership is replace the word ‘currency’ with the word ‘crisis’.

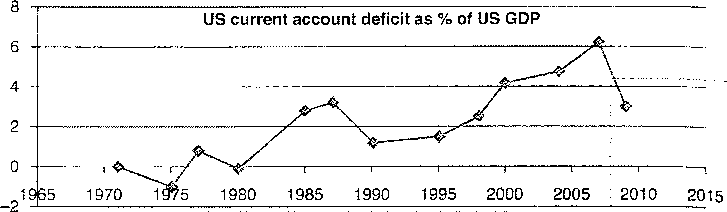

We now come to the trillion dollar question: is the Global Minotaur a spent force? That it is seriously wounded is beyond doubt. The top graph of Figure 12.10 shows the large drop in the US current account deficit, the Minotaur7s calling card. This drop, as explained in the previous section, is the cause of Europe’s and Japan’s travails, and the reason why China’s own stimulus packages (which keep the Chinese factories going on the basis of accelerating infrastructural projects) are the only thing that prevent the rest of the world from falling into a large hole.

But is the Global Minotaur really on its last legs? Or will it bounce back? Are we entering the third post-war phase of US hegemony? Or is a brave new phase beginning that features no definitive hegemon? Granted that the backbone of what the world grew accustomed to think of as Globalisation63 was the United States’ capacity to generate enough aggregate ¡demand for the exports of the great surplus countries (mainly, Germany, Japan and, lately, China), the Minotaur's decline may well signal a new world order. Perhaps then Europe’s crisis, Japan’s stagnation and China’s desperate experimentation with alternative sources of demand, are all mere symptoms of the birth pains of some new order. If this turns out to be so, the decade beginning in 2010 will resemble the 1970s, in the sense of being pregnant with a new twist in the 300-year story of capitalism.

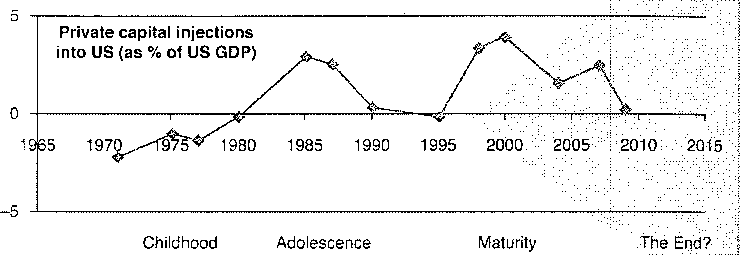

On the other hand, the announcement of the Minotaur's passing may prove premature. The middle and bottom parts of Figure 12.10 harbour some clues. The middle graph and the bottom graph allow us to juxtapose the fluctuations of capital flows into the United States by (a) foreign governments and (b) the foreign private sector respectively. An interesting choreography is apparent. When foreign private capital seems reluctant to feed the Minotaur, foreign governments rush in to fill the gap. This is almost a truism. Still, it is useful to observe the emerging pattern and the timing of the turning points.

We note that, during the Minotaur's ‘childhood’ years (1971-80), the US deficit was not yet solidified and the two flows go up and down: at the collapse of Bretton Woods, foreign governments step away from dollar assets but the foreign privateers immediately step in,

Figure 12.11 The Global Minotaur, a life. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

only to step aside after 1975 and let the governments step in with higher tributes to the Minotaur (who does not really get established before 1977 - see top graph). During its 'adolescence’, the governments take their leave and the private sector begins to send more and more capital to Wall Street. Then, after Black Monday (October 1987), the Minotaur slows down and the flow of foreign private sector capital is reduced to a trickle. During 1996-99 President Clinton’s project of reining in the government budget deficit depresses the Minotaur too and deters foreign governments. However, at the same time (and possibly because Wall Street begins the financialisation process), private foreign capital again flows in large sums. Then, at around 2000, the Minotaur enters maturity with particularly boorish energy. Interestingly, it is foreign governments that pour their ‘savings’ into Wall Street with the foreign private sector being considerably more hesitant.

After 2008, the Minotaur goes into sharp decline. Nonetheless, it has certainly not exited the scene but only receded, in 2009, to levels it had scaled in 1998. While it is early days yet,

400—--

240

2000 2003 2007 2009

Figure 12.12 Increase in US assets (in S billion) OWNED by foreign state institutions.

•W Central Bank of Emerging Economies {mainly China)

^ Sovereign Wealth Funds {mainly China plus Norway)

m State Banks

there are some signs of a possible Minotaur comeback. Throughout the crisis the Dollar’s reserve currency status has strengthened, thanks to a large extent to the mess the Europeans made with their crisis ‘management’ (which is only a euphemism for what ought to be referred to as crisis amplification). Moreover, the United States seems to attract capital from foreign governments that go well beyond the levels the latter require to safeguard their own monetary and financial stability (see Figure 12.11) which reports on the new US assets {expressed in dollars) acquired by various state-backed foreign institutions in each of the given years.

The first bar in each year corresponds to the central banks of the two main US protégés from its Global Plan years: the ECB and the Bank of Japan taken together. While both central banks continue to nourish the Minotaur, their relative importance as its feeders fades after 2003. In contrast, China’s Central Bank steps to the fore (see the second bar) and makes this role its own. Poignantly, even in 2009, when the Minotaur receded, and thus required less capital to be satiated, the Central Bank of China increased its tributes, even though slightly. This observation is strengthened further by data on capital inflows into Wall Street from sovereign wealth funds (mainly Chinese), the third bar and from (again mainly Chinese) state-owned banks, the fourth bar.

The gist of Figure 12.10 is that China has taken it upon itself to keep the Minotaur alive, at least for now. For not only does the Minotaur continue to offer China the only real prospect of renewed aggregate demand for its manufacturing sector, but, in addition, if the Minotaur dies it is very likely that the US assets that China already owns will devalue, thus causing it to lose a substantial portion of its hard-earned savings.

Will China continue to keep the beast alive? As long as the Chinese leaders entertain the hope that the Minotaur will get better soon and will start absorbing its output once again at the pre-2008 level, they will continue to nourish it. The mystery question is: at what rate? The gravest medium-term danger for global capitalism is not that China may stop sending its tributes to New York but the prospect that, while it is doing so, the Minotaur's recovery will be too limp to restore aggregate demand to something resembling pre-2008 levels. For if the

Chinese capital that flows into Wall Street is not counterbalanced by analogous volumes of manufactures crossing from the rest of the world into the United States, and in view of Europe’s love affair with austerity, our world threatens to become less and less stable.

We conclude this, unavoidably inconclusive, section with a few thoughts on the impact on the rest of the world of China’s relationship with the injured Global Minotaur. China’s startling growth affected not only its relationship with the still hegemonic United States but also with the other developing nations. Some were devastated by the competition but others were liberated from a relationship of dependence on the West and its multinational corporations. Mexico was among the first group of countries to have suffered from China’s rise Because it had chosen to invest much energy into becoming a low-wage manufacturer on the periphery of the United States (and a member of the US-Canada-Mexico free trade zone known as NAFTA), China’s emergence was a nightmare for Mexican manufacturers However, it was a miracle for countries ranging from Australia (which in effect put its vast mineral resources at the disposal of Chinese firms) to Argentina and from Brazil to Angola (which received in 2007 more funding, as direct investment mainly into its oil industry, than the IMF had lent to the whole world).

Latin America is possibly the one continent that was changed forever by China’s emergence into the Global Minotaur's major feeder. Argentina and Brazil turned their fields into production units supplying 1.3 billion Chinese consumers with foodstuffs, and also dug up their soil in search of minerals that would feed China’s hungry factories. Cheap Chinese labour and China’s market access to the West (courtesy of World Trade Organisation membership) is allowing Chinese manufacturers to undercut their Mexican and other Latin American competitors in the manufacture of low value-added sectors such as shoes, toys and textiles. This two-pronged effect causes Latin America to deindustrialise and return to the status of a primary goods producer.

These developments have a global reach. For if Brazil and Argentina turn their sights towards Asia, as they already have started doing, they may abandon their long-term struggle to break into the food markets of the United States and Europe, from which they have been barred by severe protectionist measures in favour of American, German and French farmers. Already, Latin America’s shifting trade patterns are affecting the orientation of a region which has hitherto been thought of as the United States’ backyard.

Latin America’s governments choose not to resist their countries’ transformation into China’s primary goods producers. They may not like deindustrialisation much but it is a far cry from the prospect of another crisis like that of 1998-2002 and another visit from an IMF seeking to exact more Pounds, if not tons, of flesh from their people. The only government that protests is that of the United States. For some time now, Washington has been pressurising Beijing to revalue its currency. The main reason is not so much an ambition to sell to Chinese customers more US-produced goods but, rather, to preserve the profits of US multinationals which, since the 1980s, had set up production facilities in countries like Mexico and Brazil, and which are now under threat from severe Chinese competition.64

China has so far steadfastly resisted US pressures. Though not ideologically opposed to the idea of revaluing its currency, it has learned well from Japan’s experience of bowing to American pressure to revalue the Yen - recall the Plaza Agreement of 1985. A latent standoff of sorts is therefore gathering pace. However, it is a curious tiff between two parties whose fortunes are so intimately intertwined and who know full well that if it comes to a head, both stand to lose enormously.

China has invested hugely in US assets and would see its people’s accumulated hard labour lose much of its worth were the United States to be hit by another serious crisis.

Similarly, the United States’ living standards are predicated upon continuing capital gifts from China. The US government would love to push China into a Plaza-type Agreement, like it did Japan in 1985, but lacks the clout it once had when the Minotaur was exploding with vouthful energy. China bides its time, certain that time is on its side. America knows that too but its stranglehold on the world’s reserve currency, which is not totally unrelated from the fact that it stations US troops in 108 countries, gives it hope that global hegemony will remain in its grasp.

An uneasy US-China liaison is thus the Minotaur’s poignant legacy to the post-2008 world. ‘The trend has the potential to be more divisive than any issue since the collapse of the Soviet Union’, says Walter Molano, an analyst with BCP Securities. We suspect that the future of this affair will be determined neither in China nor in the context of the US-Chinese diplomatic game but within the guts of the American social economy itself. If we are right, the post-2008 world will come to reflect the way that the Minotaur mutates, in response to external stimuli, into a new, currently unpredictable, creature.

The trouble with humans is that we cannot desist from celebrating our indeterminacy while at the same time trying our best to suppress it. Our political economics has always strived to place capitalism in a theoretical straitjacket which is nonetheless shredded into bits (at the level of theory) by our discipline’s Inherent Error and (in practice) by reality itself That was our conclusion to Book 1.

in Book 2 the same process manifested itself differently but only slightly so. We like the sound of binary oppositions and seek to position ourselves on one of their opposing sides. We imagine some almighty clash between the ‘free market’ and collective action, between the individual and the state, between on the one hand liberty and on the other hand equality or justice. In policy discussions we are consumed by arguments for greater regulation that clash with conflicting views in support of greater reliance on market forces. But it is all a mirage; our binary oppositions have dissolved before they were formed and live on only in our imagination. Capitalism has always been a system founded on state power where wealth was collectively produced and privately appropriated.

The real question, as Lenin liked to say, is who does what to whom? Its answer is a complex coalescence of grey zones, lacking the clear dividing lines of black and white. It is the sort of question that cannot, ever, be answered dogmatically but only with a sense of history aided by a critical engagement with the necessary errors of the social sciences. Those who care for the truth cannot begin with dogmas and must delve into lost truths that the more confident once understood better. Above all else, they have a duty to keep a watchful eye out for the economists’ Inherent Error.

Political economics can only begin with open-ended questions and any attempt to button them down constitutes an assault on common sense. The question for those wishing to make sense of the post-2008 world, thus, cannot be whether we should have more or less regulation of the banks? Should labour markets become more flexible? Should governments turn to tighter monetary policy or adopt looser fiscal rules? We need different questions like how can we prevent our artefacts (i.e. machines, derivatives, even ideas) from taking us over? Why do some people seem to have everything while most have next to nothing? On those who claim to have answers rooted in some ‘closed’ model, we ought to turn our back in a hurry.

Ever since capitalism shifted gear in the first decade of the twentieth century, when corporations acquired immense economic power, our market societies have been oscillating like an irregular yo-yo between tighter and looser regulatory regimes for reasons that hav* precious little to do with ‘scientific’ analyses or even purely economic arguments. The 19?q-. establishment economists were not as certain regarding the merits of unbridled capitalism a: we might now think; nor were the New Dealers dead keen on bashing Wall Street, regulating' banks and planning the economy. If this is how history panned out, it is because of force of circumstance beyond their wishes.

Keynes believed that he had a simple solution to capitalism’s tendency to stumble fall and refuse to pick itself up without a helping hand from the state. He thought that through judicious fiscal and monetary adjustments it was possible to prevent, or at least mend, depressions. He was wrong. Capitalism cannot be civilised, stabilised or rationalised. Why1* Because Marx was right. Increasing state power and benevolent interference will not do away with crises. For the more the state succeeds in bringing about stability, the larger the centrifugal forces that will eventually tear that stability apart. Crises cannot be massaged out of capitalism because, as Marx pointed out, labour creates the machines which then auto-reify, take over the human spirit and turn into its manic slave. Moneymaking reifies its own premises and the means become the end. When that happens, capitalism itself is destabilised. The liberal state, at that juncture, can only look on in stunned disbelief as the whole edifice falls apart, and gleaming machines end up idle while workers keen to labour remain jobless.

Marx too thought that he had a simple answer for capitalism’s troubles. Convinced that its own deep contradictions would, effectively, force it to commit suicide, he believed that a new rational order (one that does not constantly undermine itself, by turning workers and capitalists into capital’s slaves and confining generations of workers to the unemployment scrapheap in the process) was inevitable. He, too, was wrong. Capitalism will not just go away under the strain of its admittedly titanic incongruities. Why? Because it has Keynes (or someone with similar ideas) on its side. In its bleakest moments, Keynesian interventions give capitalism a second wind; and a third and a fourth, if need be. Regulation and state intervention do save capitalism from itself, in the limited sense of preserving property rights and buying time for capital to overcome the authorities’ renewed ambition to rein it in.

The post-war period, with its two phases, is an apt illustration. The Global Plan was the offspring of the Great Depression and the War Economy. It sought to impose a rational set of rules onto the global capitalist game. Never before had such a wide-reaching plan been thought up and implemented by so few for the benefit of so many (give or take a few million Vietnamese, Indonesians, etc). It kept both inflation and unemployment to levels hardly detectable by the naked eye and promoted sustained growth that no one had thought possible before. However, its success was its worst enemy.

The hegemon minding the shop decided to help itself to the till. At first that transgression stabilised the Plan and reinforced the tendency to play fast and loose with the rules. However, little by little the stability and trust eroded and gave their place to suspicion and tumult. The hegemon felt threatened and, to preserve its hegemony, it chose the path of partially controlled disintegration of the global order (or the proverbial shop). Through orchestrated energy price hikes and monetary crises, it brought into being a new asymmetrical, unplanned order which, nevertheless, guaranteed it a medium-term capacity to live beyond its means, courtesy of other people’s money. Like a Global Minotaur, it buttressed a unique form of stable disequilibrium in which a heavily asymmetrical growth pattern was accommodated and financed by large daily capital tributes from the rest of the world.

Once the new quasi-stable disequilibrium was established, instead of letting things be, the beast spawned a new phenomenon: financialisation — a reaction to the combination of

(a) areat capital flows (rushing into New York to provide for the Minotaur) and (b) extremely jow" interest rates, reflecting both the procured stability and the fact that, since everyone wanted to supply the hegemon with capital, the latter could afford to reduce the price of ''borrowing inordinately. Thus, the banks inundated the globe with their private money and promoted unsustainable growth rates, especially in unproductive assets like real estates and derivatives.

Then the bubble broke, the private money burnt out (see Box 12.20 for a description) and apjng-p°ng game began with private losses turning into public debt (as state officials, often ideologically committed against any form of government intervention, were compelled to intervene), and public debt becoming the field on which cunning financiers planted the seeds of new, short-lived, private money. The problem with this type of cycle is its irregularity. Like an out of control pendulum, it threatens to exhaust the state’s capacity to come to the market’s rescue and, vice versa, to deplete the market’s ability to bounce back because of a collapse of the state’s financial position.

Could the authorities have prevented this vicious circle that is, clearly, spinning out of control and threatening the world with a new variant of the 1930s? There is no doubt that the authorities could have done better. However, it is not our view that government could have, however brilliant, stood in the way of the Minotaur and prevented the vicious circle itself. Alan Greenspan, the iconic Chairman of the Fed (from which he retired just before the Crash of200S) put it ever so succinctly in a recent article:

I do not question that central banks can defuse any bubble. But it has been my experience that unless monetary policy crushes economic activity and, for example, breaks the back of rising profits or rents, policy actions to abort bubbles will fail. I know of no instance where incremental monetary policy has defused a bubble.65

We agree wholeheartedly with Greenspan. Just as there is no such thing as an optimal degree of income redistribution that can deliver social justice without pushing the rate of capital accumulation below that which is necessary to sustain capitalism’s vigour and growth,66 there is no such thing as an optimal monetary-fiscal policy mix that can deflate the forming bubbles (at a time of disequilibrium quasi-stability) without crushing economic activity and employment.

Box 12.20 The Crash of2008 summarised by Alan Greenspan (Fed Chairman 1987-2007)

Global losses in publicly traded corporate equities up to that point were $16,000 bn (€12,000 bn, £11,000 bn). Losses more than doubled in the 10 weeks following the Lehman default, bringing cumulative global losses to almost $35,000 bn, a decline in stock market value of more than 50 per cent and an effective doubling of the degree of corporate leverage. Added to that are thousands of billions of dollars of losses of equity in homes and losses of non-listed corporate and unincorporated businesses that j could easily bring the aggregate equity loss to well over $40,000 bn, a staggering two-| thirds of last year’s global gross domestic product. j. _

Why not? Our answer is the same as the one we gave in Chapters 4 and 5 to the question of why labour cannot be quantified and reduced to a mere input analytically equivalent to electrical power, and to the question in Chapters 7, 8 and 9 on the reasons why investor risk and uncertainty cannot be captured by some mathematical model. It is because we live in a world combining (i) a system of private appropriation of collectively produced wealth with (ii) the ontological indeterminacy (see Chapter 10) springing from the human animal’s curious penchant for

(a) producing in a manner that no mathematical function can capture without missing the essence of human creativity and

(b) creating a higher order form of uncertainty (through the infinite feedback effec t between human belief and action) which no mathematical function incorporating well-defined probabilities can encapsulate.

Thus to believe the idea that prudent governments and tight regulation could have prevented the Crash of2008 is to seriously misunderstand the irrepressible tumult that is capitalism; the unavoidable turbulence that just happens when we mix liberty with private property; creativity with expropriation; doing things for their intrinsic value and reducing every value to its market determined price; a robust Global Plan for organising capital and trade flows worldwide with conglomerates that are motivated solely by a primordial search for monopoly power and machine-like labour.

Alas, this very basic point about an elemental clash at the very foundations of our social order is so hard to keep on our intellectual radar screen, especially when most people (if not all) who spend serious time scrutinising the current crisis have been trained to think about capitalism within a mindset in which capitalism is impossible.

Box 12.21 Why regulation cannot prevent crises: A rather modern view

An ignorant and mistaken bank legislation, such as that of 1844^5, can intensify this money crisis. But no manner of bank legislation can abolish a crisis [..,] In a system of production, in which the entire connection of the reproduction process rests upon credit, a crisis must obviously occur through a tremendous rush for means of payment, when credit suddenly ceases and nothing but cash payment goes... At the same time, an enormous quantity of these bills of exchange represents mere swindles, and this becomes apparent now, when they burst. There are furthermore unlucky speculations made with the money of other people. Final ly, they are commodity-capitals, which have become depreciated or unsalable or returns that can never more be realized. This entire artificial system of forced expansion of the reproduction process cannot, of course, be remedied by having some bank, like the Bank of England, give to the swindlers the needed capital in the shape of paper notes and buy up all the depreciated commodities at their old nominal values. Moreover, everything here appears turned upside down, since no real prices and their real basis appear in this paper world...

Karl Marx, Capital Volume 3, part V, Chapter 30, j Marx (1894 [1909]), pp. 575-6 j

Box 12.22 Failure pays

Nothing perseveres like privilege’s determination to reproduce itself. During the Global Minotaur's undisputed rein the free market promoted the notion of choice by parents, students, patients, defendants, etc. In practice it meant that children were increasingly selected at the best schools on the basis of their parents’ income, the sick j received treatment more and more in tune with their wealth, justice was denied to I those who came from the wrong part of town. Similarly with macroeconomic I management: during the Clinton administration, Larry Summers’ policy decision to i deregulate Wall Street completely and utterly contributed to the financial sector’s | uncontrolled gallop into near oblivion. At the time Timothy Geithner was his Under-j secretary. Guess who was to be summoned to clean up the mess when President Obama | came to power eight years later? Summers and Geithner of course! The explanation? I Who else could be trusted with such a big job and all the privileges it brings to its | bearers? Once capitalism grows sufficiently complex, failure pays. Eveiy crisis boosts j the incumbent’s power because they appear to the public as the only good candidates

j for mopping up the mess. Think of not only the Geithner.....Summers Plan of 2009 but

f also the IMF-ECB-EZ mechanism (see Box 12.18) that is meant to sort out the | post-2010 European debt crisis. The trouble is that the ‘solutions’ implemented by the original creators of the problem create even more centralisation and complexity which, I in turn, further boosts the culprits’ indispensability... does any of this remind the 1 reader of something from Book 7? Perhaps the sciences’ most peculiar failure - a j discipline whose discursive power grows as it goes from one sad theoretical failure | to another?

Summing up, capitalism does indeed go through cycles. Not of the ‘real business’ variety (see Box 2.11), which pack as much analytical power as a hen packs flying power, but cycles between periods when regulation is tight (usually after the horses have bolted) and periods when government applies a ‘light touch’ (when stability seems to be the order of the day); between periods of active state planning and periods of negative macroeconomic engineering. Arguably, the post-war period saw the most violent swing from one to the other as the unprecedented Global Plan gave its place to the matchless Global Minotaur.

The swing was so violent that something else, something brand new, emerged from the guts of that transition: financialisation. It upped the stakes by allowing institutions that produced nothing tangible to generate almost as much private money as there was public money. The monetary explosion distorted everything within the global social economy, causing all sorts of cycles to increase in amplitude. The higher the cycle went the harder the fall. Of course, those who hit the floor hardest where not the same people who had benefitted from the upswing.

The Global Minotaur era, and its end in the Crash of2008, has added another wrinkle to our story in Book 1. Chapter 4 expounded our hypothesis that humans are constantly taken over, at least in spirit, by their mechanical artefacts but, because the takeover can never be complete (due to humanity’s stubborn resistance to turn fully into an automaton), crises erupt periodically. The Global Plan was meant to iron out these crises, by means first touted by

Keynes and then developed by the New Dealers. It failed, perhaps for reasons von Hayek (among others) had important things to say about; mainly, the twin ideas that:

(a) no plan, however brilliant, can reflect its constituents’ ever-changing capacities and needs: and

(b) no government, national or local, can be trusted to act in the public interest because public interest is as ill-defined as labour’s, industrial capital’s and speculative capital's sentiments are grossly indeterminate.

What the Minotaur added to the story is a capacity for the theoretically inept neoclassical models of macro and financial economists to lend a helping hand in the manufacture of private money; a process that has added substantially to capitalism’s fully endogenous instability. At last, neoclassical economics became part and parcel of the Spirit of Capitalism exacerbating its inherent propensity for unsustainable booms and recessionary sojourns. The economics functional to the Minotaur's interest consequently evolved from theories that were, at worst, quaintly irrelevant to techniques essential in the manufacture of financial weapons of mass destruction. Thus, capitalism’s endogenous failures at last joined forces with economics’ Inherent Error to produce crises bigger, juicier and more catastrophic than ever before.

We ended the last chapter with Paul Volcker’s effective announcement of tine-Minotaur-circa 1979. We end this chapter with the words of his successor at the Fed, Alan Greenspan which, to us, sound like the Minotaur's eulogy. In this extract Greenspan is addressing the Congressional Committee for Oversight and Government Reform on 23 October 2008, presided over by California Democratic Senator Henry Waxman,67 Waxman conducted the hearing in an aggressive manner, at a time when the American public were seething at what had gone down, demanding of Greenspan to explain the degree to which it would be true to say that the Fed, under his stewardship, had set the stage for the Crash of2008.

greenspan; Well remember that what an ideology is, is a conceptual framework with the way people deal with reality. Everyone has one. You have to. to exist, you need an ideology. The question is whether it is accurate or not. And what I’m saying to you is, yes, I found a flaw. I don’t know how significant or permanent it is, but I’ve been very distressed by that fact.

waxman: You found a flaw in the reality?

greenspan: A flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works, so to speak, waxman: In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology, was not right, it was not working?

greenspan: That is - precisely. No, that’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I have been going for 40 years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.

We believe that Greenspan was being perfectly sincere in uttering, under stress, the above words. The model of the world that he courageously calls ‘his’ was the dominant paradigm that began life in or around 1950 (see Chapter 8) and which ended up the official ideology ot those who saw it as their life’s work to do the Minotaur's bidding. In this book, we have also (unkindly perhaps) called it, among other things, the Econobubble; the economists' Inherent Error on steroids; a mathematised religion, etc. Along with the derivatives market and the reSt of the financial and real estate bubbles, the Econobubble, Greenspan’s model-cum-¡deology, burst too in 2008.

We feel a sense of pride in Greenspan’s Confession. Of all the confessions we have encountered by powerful men caught up in the whirlpool of historical reversals, his was the most sincere and intellectually robust; a downright affirmation of truth’s ultimate importance. It is particularly helpful for younger minds who need role models, examples of intelligent people who change their minds drastically against the forces of ideological inertia and even at significant personal cost. It is a rare phenomenon and as such must be cherished.

It is also helpful because it points to the origin of the dogma that supported countless individual and institutional choices that led the world to crash in 2008. It was the same dosma that gave mainstream economists the conviction to ‘close’ their models by means of untestable meta-axioms (recall Chapters 7, 8 and 9); the same pool of elixir that the financial engineers used in order to mask the stench of the parameters within the formulae with which they priced the CDOs; the same song sheet on which paeans to the markets were written in the language of the Formalists who scored such an unexpected triumph in US economics departments from 1950 onwards; the same mindset that informed decision makers in Brussels, Washington, the World Bank and the IMF to script policy papers which ended up diminishing the life prospects of so many and for so little sustainable gain.

If we were to point to a single silver lining from the calamitous developments of the post-2008 world, Greenspan’s Confession will do nicely.

The Recycling Problem in a Currency Union1

by George E. Krimpas

PROLEGOMENON: the recycling problem is general, not confined to a multicurrency setting: whenever there are surplus and deficit units, i.e. everywhere, real adjustment must be either upward or downward, the question is which. An attempt is made to formulate the recycling problem in terms of EMU. But while the problem seems clear the resolution is not. A minimalist solution is proposed through a detour consistent with the Maastricht rules, inadequate as this is, it highlights the limits of technical arrangements when confronted with political economy, namely the inability to set operational rules of the game from within a set of axiomatically predetermined constraints dependent on the fact and practice of sovereignty. Even so, an attempt at persuasion through clarification of the issue may be a useful preliminary, in particular by highlighting the distinction between recycling and transfers. Some of the paper’s evocations, notably on ‘oligopoly’, may be taken as merely heuristic.

The only economy which does not have an external surplus or deficit problem is the closed economy and, since Robinson Crusoe time, there aren’t any. By contrast, the situation of any open economy is eternally asymmetric; if in surplus it can carry on merrily, at least until something untoward, exogenous or perhaps internal, turns up; while, if in deficit, it is under pressure both externally and internally, additionally to any exogenous event.2 Keynes (1980: 27) put the problem succinctly in his very first official memorandum, dated

8 September 1941, on the proposal of a Clearing Union, thus:

It is characteristic of a freely convertible international standard that it throws the burden

of adjustment on the country which is in the debtor position on the international balance

of payments, - that is on the country which is (in this context) by hypothesis the weaker and above all the smaller in comparison with the other side of the scales which (for this purpose) is the rest of the world, [emphasis in the original]

A definition of the problem and its resolution which was half-scuttled on the tortuous way to Bretton Woods, nevertheless functioned reasonably until abandoned some 25 years later.

Keynes himself, having Tost’ the decisive argument for symmetrical adjustment of fixed but adjustable exchange rates in his own, multicurrency clearing union, did not further areue the case of a fully-fledged single currency union’s possible additional or alternative internal arrangements. Yet after the nameless, dogmatic years in the doldrums between the Smithsonian and Maastricht, such a currency union eventually turned up in a tiny part of the globe called Europe, partly in response to the abandonment of Bretton Woods but also, cm-daily, subsequent to the grand design of Europe led by the Marshall Plan and some peculiar pairs3 of Enlightened European statesmanship constructing the Franco-German integrating dynamic, the rest following.

But the Euro-Maastricht architects constructed an EMU with the ‘E’ effectively left out. The intra-union imbalance problem was thought settled by the fiscal rules; it was not, and not because the fiscal rules were in practice inoperative; it would have turned up even if thev were. The nominal uni-currency national accounts do not account for differential intra-union competitiveness, only at best indicate it afterwards. ‘Real’ as distinct from now non-existent nominal exchange rates, conventionally proxied by intra-union differential unit labour costs [but see further below on ‘oligopoly’], remain to create ‘external’ intra-union imbalances within the union even with balanced [fiscal] budgets. To focus the argument on fundamentals, not accounting devices, this latter condition will be assumed to hold throughout - it is, perhaps, when taken by itself, the least constraining of the Maastricht rules, neither preventive cure nor remedy for the recycling problem.

To illustrate the oddity of the ‘internal’ imbalance notion, imagine a sub-lunar visitor to China where he/she observes a Chinaman holding a dollar note. The visitor immediately knows where that one came from: ‘it’ has crossed a monetary border. As for its destination he/she may ask the bearer, who being a law-abiding person is already on his/her way to the office where the foreign body in his/her hands is to be exchanged for what in his country is called ‘money’. The receiving authority will then do its mediating job, likely ending up by holding an alternative asset yielding some return, most usefully American treasuries, thus recycling the value of the item, helping the world to sustain deficits elsewhere - Adam Smith might have said this was no part of anybody’s intention, in the present context falsely. But what if the sub-lunar visitor were to land in Germany there to observe a German person holding a Euro note? Nobody, including the bearer, would have the means to know where that token body came from; it is not ‘it’ but just money. Borderless transition of the token of value annuls the question of its origin; its destination is as mystical. Who and by what observing; instrument can tell whether that Euro note is on the wing or heading for a temporary abode or plain hoard, in principle immune from the necessity of intermediation? Yet in this one-money sub-lunar world there are still surpluses and deficits and their myriad offshoots; the problem is their implications when the surplus and deficit units are sovereign states. So what precisely is the internal, intra-union ‘external’ imbalances ‘problem’; what rules might be devised to meet it in a union-wide acceptable form? The ongoing and perhaps deepening crisis is not crucial to the argument that follows, though it serves as backdrop and certainly as origin for concentrating the mind wonderfully.4

It is convenient to think of country-members of a currency union as composed of differentially powerful oligopolists,5 the predicate ‘power7 leading one to think in terms of (partial equilibrium) ‘neo-mercantilist’ or ‘vent for surplus’ national strategies, though eventually coming up against those ultimately constraining (General Equilibrium) identities - for we cannot all be simultaneously successful neo-mercantilists.6 The stylised facts of the currency union disequilibrium case are then summarised thus:

(a) The definition of the problem is assisted by the fact that EMU is only marginally in surplus with the rest of the world: to the extent that some member countries are in surplus with the rest of the world, that part of their overall surplus can be ignored as being someone else’s problem, so the effective stylised fact is that there is no rest of the world; ail ‘external’ imbalances are interna! to the currency union.

(b) The currency union regime thus being the whole world is only a union insofar, positively, as free and stable - a tall order (for labour markets even taller) - markets rule the game, but also, negatively, insofar as oligopoly,7 as the prevalent subspecies thereof, induces a dynamic asymmetry of endogenous action and response which regime rules allow but cannot handle, thus triggering the equivalent of Keynes’ diagnostic statement quoted above: thus, ultimately, insofar as - though in merely accounting terms - fiscal imbalances are concerned, the rules can only work downwards, the asymmetry is dynamically part of the system and cannot be corrected. The otherwise unseeable (by the national accounts) ‘causal’ imbalances in the real economy will be reflected in falling real wages and employment.

Without naming names, the currency union equilibrating game is thus intra-union competitively disinflationary; taking unit labour cost as the proxy metric, oligopolistic power will turn up on either the numerator falling or the denominator rising - real wages must fall or productivity must rise. Oligopoly is precisely the power to do either or both, differentially. It is also the differential power to enforce unemployment or anything else interfering with the ‘vent for surplus’ overarching objective, the ultimate raison d’être of any respectable oligopolist. But the resulting deflationary underemployment equilibrium is dynamically unstable, asymmetrically affecting the currency union’s members, a game without endogenous issue till vanishing point, a subzero equilibrium solution eventually detrimental to the surplus unit - if only the world could wait for it.

The question of the present exercise is, given the Maastricht-EMU rule-book as is, can there be an acceptable mechanism for recycling surpluses so as to offset the deflationary impact of deficits? - the answer being, if not plainly ‘no’, then decidedly unpleasant unless some additional not incompatible rule may be devised and accepted. To investigate this we must look at the flow of ‘external’ surpluses once earned and trace the path of their eventual destination.

Since by definition, in a currency union all flows are denominated in the same currency, it will simplify investigation to assume that the union consists of two countries, one in surplus, one in deficit, taking the most favourable benchmark for the exercise: both countries have zero fiscal deficits and are, however mediately, equally financially served (in terms of collateral, etc.) by the single currency union central bank called the CUB, assumed subject to present European Central Bank (ECB) rules.8 The ‘single market’ in everything then implies a ‘single price’ for everything insofar as everything is the same - which it is not9 -thus, in the oligopolistic setting of the modern world, also differential markups and margins therefore profits, the surplus country being the differentially high profit country. Tracing the path of profits is then tracing the path of surpluses.

The question now is: where do these profits go? Is there financial intra-union but intercountry intermediation of profits or are differential profits so to say ‘oligopolistically’ intracountry retained, effectively intra-country ‘hoarded’ thus ruling out surplus recycling?

But the private sector financial system is itself ruled by asymmetry, surplus units are ever more creditworthy than are deficit units, etc., therefore the dynamics work out so that surplus country profits are retained by the surplus country and cannot be recycled to the benefit of the deficit country (net of foreign investment plus transfers of all kinds by the surplus to the deficit country). The original deflationary impact on the deficit country is thus not recyclable.

In this case, Keynes’ Essential Principle of Banking50 is nullified; there can be no recycling since there is hoarding prior to banking. So the question becomes, can the currency union’s CUB act anti-asymmetrically to offset this bias - can the Tender’ turn round to become ‘spender’, let alone, in crisis, the before-the-Iast resort lender and presently the first resort spender?

It possibly can, if it subsumes the functions now entrusted to the European Investment Bank (EIB), with the latter’s rules as they now stand - the EIB can lend to both the private and the public sector of any currency union country as well as others, not on collateral but rather on prospective yield; noting also that public borrowing from this source need not, bv present rules, be counted in the national debt.11

This institutional twist represents a novel degree of freedom for the adjustment process, a window of opportunity akin though more proactive to the conventional discount window of a standard central bank in normal times. The CUB-EIB thus reconstructed is then more than a lender of last resort to the financial system - though by rule explicitly not currency union governments - it is also ‘like ’ a fiscal authority to the extent that it is a spender of first resort, albeit on commercial rather than distributional criteria: the principles of Maastricht-EMU are not disturbed. But EIB finance is also hereby undisturbed, its credit worthiness is if anything enhanced, it can directly and indirectly draw surplus profits arising from external surplus into proper and appropriately prudential intermediation directly aimed at productive profit-yielding investment.

To the extent that such an institutionally based recycling device is effective, it obviates the deficit government’s investment needs to borrow from the market, by construction on terms more onerous than those available to the surplus government’s country. For the CUB-EIB construct, apart from borrowing on its own creditworthiness, which should be similar if not on the grounds of scale superior to the creditworthiness of the surplus country, can, as part of its primary inflation targeting mission, expand credit autonomously just like any central bank can within its remit; but in this case CUB-EIB credit expansion in the form of enhanced liquidity would be linked to and locked by the extent to which the deflationary impact of un-recycled surplus works against the CUB’s inflation target.

There is here implicitly a growth-and-employment objective which has slipped into the argument: but is this not ever so in the reality of actual practice? And, this being the case, is it not enticing for formalist enthusiasts to devise the right rule transforming, say, output gaps and the like (e.g. ‘foreign gaps’, let alone unit labour cost gaps) into algorithmic solutions concerning the CUB’s accommodating finance to his/her EIB brother/sister, perhaps ‘modelling’ these two on the fantastic Washington twins?

Not necessarily, in this line of thinking. The revolving fund of finance which is at the back of the preceding argument does not preclude the notion of growing financial support for a growing currency union economy hopefully aiming at stable full employment, not rule-based but judgement-based, a political matter here taken as exogenous.

This may be taken as fudging the issue: it is not an original thought that the EiB should be brought into the picture, it has already been so - nor, which is perhaps more important, have the orders of magnitude being taken into account other than in qualitative terms: what proportion of imbalance should EIB finance offset that would correspond to a re-cyclical revolving fund equilibrium? - here tempting the algorithmic response above rejected. The issue now and beyond is rather not how much but to what purpose, in regard particularly to the problem of institutionally evolving towards the solution of recycling surpluses, not to the current short-term problem of boosting investment expenditure, immensely necessary as tins is Immiseration, either in the form of falling real wages or unemployment is the road to destruction of what still bears the name of Europe. In a nutshell, the EMU must start on the long road to bring the ‘E’ to conjoin the ‘MU’. This all has to do with investment, not consumption. Only this can be the offset for oligopolistically crippling vent for surplus. Recycling is thus not a redistributive transfer, let alone bailout, from the surplus to the deficit fiscal authority, but a straightforward application of the banking principle.

It would mean that the effective EIB spending leg of the CUB-EIB construct has a lower-than-the-market financing cost, as dictated by the CUB’s intervention rate which is the prime instrument directed to achieving the counter-inflation target. By being consonant with this would also help to enrich the CUB’s armoury vis-à-vis the yield curve, thus enhancing the non-inflationary growth prospects of the currency union as a whole. If the argument is correct, it may be only an acceptable beginning, perhaps in a small way, but it may instruct the course for the future. In fine, an otherwise desired sound financial policy would be compatible with a non-deflationary mechanism of adjustment. The policing rules of the mechanism are simple and should be obvious; but these fall under the head of politics.