1 A Crisis in Our Midst—No Coherent Knowledge Base

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Organizations are made of conversations.

—Ernesto Gore

In our profession, a simmering crisis has been building, yet most educators do not even know what the crisis is and how dire the situation has become. The crisis is that, as a profession, education has no coherent knowledge base about standards for excellence. Paraphrasing from Hargreaves and O’Connor (2018), professional collaboration is about creating this deeper understanding, which advances our knowledge, skills, and commitment to increase learning.

Over the course of a career, teachers develop deep knowledge about how to support the learning process and student growth and development. Yet these insights are rarely shared within the larger community of professionals. Instead, educational methods cycle from one new program to the next, with little attention to how professional knowledge is developed and shaped to create a communal understanding. The end result is that educators have no control over their professional narrative or the standards used to measure excellence. There are historical reasons why other professions have not experienced the political whipsaw so prevalent in education, and educators would be well served to pay attention to this history.

Knowledge Coherence Grows Knowledge Legacies

Over the past 100 years, other professions have amassed what have become large knowledge legacies—essential bodies of knowledge that were developed through coherence over time, disseminated through printed tomes, and used to ground conversations. With the advent of the digital age, this knowledge has become accessible in ways once not thought possible. Most notably, lawyers have case law and sources such as Westlaw; doctors have the National Library of Medicine now digitized as Medline; and accountants have Financial and Government Accounting Standards. Science has basic research standards and a growing body of “consensus standards” in the subspecialties. These knowledge bases are additive and adaptive as they continue to grow and change with the profession. Over time, professions that take the time to find coherent patterns, which include debated topics, can speak with an authentic voice; by doing so, they maintain a level of professional integrity that educators can only dream about. As Hargreaves and O’Connor (2017, p. 1) state, “No profession can serve people effectively if its members do not share and exchange knowledge about their expertise or about their clients, patients, or students they have in common.” There is no question that knowledge builds capacity over time as it is passed from generation to generation.

In education, the status quo has hidden behind the idea that teaching is more art than science and hence, like art, difficult to quantify. Teachers often cheer when assured, “You are the professional; do your best work.” What is not stated is that this “best work” is more often done in isolation, and it is a rare school that has figured out how to capitalize on this vast storehouse of applied knowledge. A wise administrator once ruefully commented that when a teacher retires all that knowledge goes with them to the grave. There is an African proverb that sums this up: “When an old person dies, a library burns.” We would add—what an unnecessary waste.

In large part, this historical failure to develop a knowledge coherence is because education is a human endeavor—learning appears to be as unique as fingerprints—making it difficult to find patterns, definitive solutions, or even agreement on basic tenants. Hence, as a profession, teaching has been controlled, even whipsawed, by outside political forces. When national debates further divide the community, as they did in the 1990s with the “curriculum wars” (and are now happening with the Common Core State Standards, or CCSS), the decisions are tossed back to local schools, which often have no understanding of the initiating beliefs or even what is being debated. These debates have a way of polarizing groups and developing contempt before investigation. These words may seem strong, yet they speak to a troubling truth. Teachers, and the parents in support of these teachers, line up to advocate for what they already know, and in the heat of the moment, all conversation is lost. In the void, governing bodies rush to simple solutions, failing to examine the underlying beliefs and assumptions.

For example, in the 1990s one school board in a university town ended conflicts by adopting two different algebra books: If you lived on the east side of town, you received one curriculum; if you lived on the west side, another. While this town was committed to democratic practices, they could not find a way through the conflict that arose around two different textbooks.

These kinds of compromises are not uncommon when communities do not have the conversational tools to open up deep understandings; as a consequence, decisions get made from a limited perspective in order to stop the conflict. This conflict avoidance serves to deepen the unspoken divides and creates crises fueled by ignorance. And most damaging of all, this glossing over of the real truths exhausts those involved in the implementation and confuses parents and students. Instead of an opportunity for professional learning, those involved tend to become even more defensive. No wonder so many teachers are leaving or plan to leave the profession as soon as possible.

An example of a better way to make policy would be to ask the educators in conflict to reconvene, possibly with someone skilled in professional conversations, to identify the similarities and differences between these two different approaches. Any one of the Nine Professional Conversations in this book could be used to open up a dialogue about these differences. The key is that agreement is not what is sought, but rather a coherence, which means that ideally the professionals will work to find overlapping understandings and to clarify points of disagreement. Just as in successful interest-based collective bargaining, when professionals can “agree to disagree” they can then move to more productive conversations. Furthermore, these debates about textbooks and programs distract from the real issues confronting educators, which is the development of a coherent understanding of teaching and learning beyond these prescriptions to what really works in the classroom.

Another example comes from the drama that has played out in the current debates about the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) that were initiated by politicians to create an internationally competitive education system. One year, teachers work hard to implement the CCSS, only to find that their state has repealed these same standards in subsequent legislative sessions. This policy whipsaw leaves teachers without direction and further undermines any desire to work toward a common understanding—the genesis of knowledge coherence. As one teacher put it, “All the public debate about standards makes me want to go back in my classroom and shut the door on the world.” Meanwhile, the politicians, distracted by a polarizing debate, have ignored some of the best practices from a growing body of knowledge about what makes other countries’ educational systems successful. Policy makers would be well advised to pay attention to the rest of the world. (For more information, see Surpassing Shanghai [Tucker, 2012]; Finnish Lessons 2.0 [Sahlberg, 2015]; The Flat World and Education [Darling-Hammond, 2010]; and Cleverlands [Crehan, 2017].)

Teachers Voice the Need for Knowledge Coherence

Wise teachers articulate the desire for conversation and want to become more expert, yet their voices are drowned out in all the rhetoric about failing schools. Sarah Brown Wessling, 2010 Teacher of the Year, said, “When I look at the standards, I don’t see a document that tells me what to teach or gives me a curriculum; rather, I see an underlying organization that gives us collective purpose.” Another teacher from a charter school, Darren Burris (2013), remarked, “To me, the Common Core represents an empowering opportunity for teachers to collaborate, exchange best practices, and share differing curricula—because a common set of standards is not the same thing as a common curriculum.” There is a huge distinction between consultants telling teachers about the standards and teachers spending quality time digging deeply into the assumptions, beliefs, and strategies as part and parcel of implementation. Leaders must find creative ways to engage teachers in meaningful conversations about the changes they wish to make. Conversations matter for the implementation of any curriculum.

Well-articulated conversations open up knowledge coherence and help peers understand their differences in order to foster the development of knowledge legacies. For example, in Washoe County, Nevada, Aaron Grossman, a teacher tasked with the CCSS implementation, found himself in crippling debates about the purpose of the standards. The standards were not his, and he had no desire to advocate for or against the standards; but he did want the teachers to be informed consumers. So he reached out through the Internet to the knowledge base and provided the teachers with unfiltered information that began to answer some of their questions. He encouraged teachers to follow suit. This process and the conversations that ensued led to the development of agreed-upon “Core Practices.”

As is so often the case, administrative leadership changes ended this committee, but the group’s learnings have been memorialized on the Internet (www.coretaskproject.com). A high point for Grossman was when the team decided to reach out to the coauthors of the literary standards, David and Meredith Liben. Soon, these teachers were collaborating with these authors to develop core tasks to support the new standards. With the Libens, they created a short video that describes the high points of the project (Grossman, 2017). Through video and Internet links, these educators have created a lasting legacy that documents their knowledge.

While this book is focused on changing one school at a time, long-term changes need national support and funding to create a professional knowledge base. (The current government-sponsored What Works Clearinghouse [WWC] has not proven the test of time and is wholly inadequate; furthermore, it has been plagued by the same program debates as the school board described earlier.) We are confident that if teachers were given the power—the voice—and the national technological support to develop a coherent knowledge base, the profession would then take control over “what works.” We would come to understand what really works and fulfill the mandate of a democracy—to educate its citizens to the highest level possible. We would begin to appreciate the vast storehouse of knowledge that creates excellent teaching and would begin to change the way we develop teachers from novice to expert. The problem is not the desire to have these conversations, but the ability to actually carry them out, especially on topics that may become contentious or controversial. For now, unless you are a policy maker and can impact the larger arena, we ask you, the educator, to focus on your own school and your own conversations so as to become a beacon of hope for those around you.

Professional Conversations Matter

While the long-term crisis involves a lack of knowledge coherence and limited knowledge legacies in the educational profession, the looming short-term crisis is fueled by our inability to sustain professional conversations about what matters in schools. The purpose of this book is to change that situation and to offer practitioners nine different kinds of conversational frameworks that have the potential to change the way we work in schools.

If you move conversations to a professional arena and seek all voices in the room, disagreements are certain. We offer these conversational methods as catalysts for generating meaningful, professional conversations. The goal of this book is not the conversation, but rather bringing a coherent teacher voice into the development of a robust understanding of teaching and learning—building the profession they deserve.

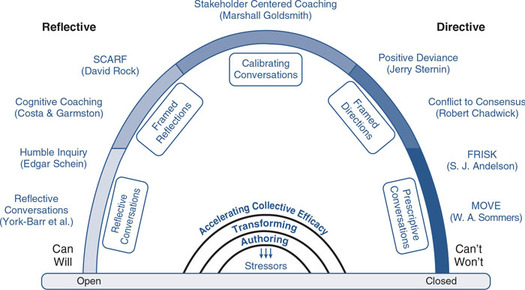

By way of introduction to the Nine Professional Conversations, we organized the conversations from open to closed, as noted on the bar at the bottom of the graphic. By this, we mean that the agendas for conversations on the left ebb and flow around the interests of the group; closed agendas, those conversations on the right, require that the group focus on an identified need.

We further divided the conversations into five categories, which are listed in the boxes under the Professional Conversation Arc as follows: Reflective Conversations, Framed Reflections, Calibration Conversations, Framed Directives, and Prescriptive Conversations.

- ■ The two Reflective Conversations open up the space for collective exploration and guide groups in finding out more about each other’s professional practices.

- ■ The Framed Reflections are more goal focused and assist in bringing focus to group work.

- ■ For Calibrating Conversations, we chose only one conversation because it focuses more on the ways leaders can use feedback from their constituents to improve. This models what groups can do when they work together rather than simply relying on external data points such as testing.

- ■ As the arc swings down to the right, Framed Directives include approaches designed to move groups to productive workspace. These can be useful when groups need to find out more about each other’s differences.

- ■ Finally, Prescriptive Conversations identify two ways to consider tough issues that need hard conversations. While prescriptive conversations may seem odd in a book mostly about open-ended, reflective conversations, the reader will be surprised to learn that the real art in tough conversations is bringing forth a reflective stance. Consider the difference between two employees: One says, “I did not know my behavior was offensive and I will change,” versus another who says, “I don’t agree with you, and I should be able to say what I want.” One demonstrates that he or she “can and will” change, while the other says she or he “can’t and won’t” change.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

Consider the professional conversations that have been part of your work life:

- ■ What attention has been given to the quality of these conversations?

- ■ How have leaders modeled effective conversational practices?

- ■ Think of a professional conversation that made a difference.

- ■ What do you most remember about why this conversation was so important to you?

Conversations are an essential professional function, and skill building and practice are required for professionals to learn how to have conversations that matter. Conversational skill creates its own set of professional demands and knowledge needs. Because teachers spend most of their professional lives talking with students, they are at a disadvantage as a profession. Adult conversations in schools typically follow unexamined conventional norms, adequate for most day-to-day interactions, but inadequate for deep dialogues about teaching and learning. For the purposes of this book, we have chosen conversations that have proven the test of time and have brought us the best results. While we describe each conversation by its distinguishing characteristics, they can be interchanged and combined as the need arises. Indeed, we often pull strategies from different conversations and combine them. We might start with an open-ended, reflected conversation, only to discover that the group needs focus (so we might shift to a framed reflection) or that the group needs data (so a calibrating conversation is necessary).

Without skill and grace in the art (and now science) of the conversation as identified in this book, differences are ignored or pushed aside. These unresolved conflicts create invisible divides, limiting the capacity of any community to grow and learn together. This limited capacity shapes the quality of the conversation and defines a school culture as closed rather than open to new ideas. Art Costa often reminds us, “If the teachers are not in a mentally stimulating environment, why do you think they will create it for kids?”