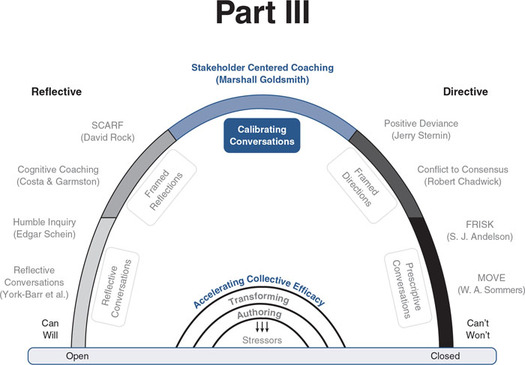

Part III Calibrating Conversations—Conversations at the Tipping Point From Outside In

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

As we reach the top of the Professional Conversation Arc, the foci of the conversations shift from self-directed learning toward other-directed learning. The first four conversations identified in Part II focus on bringing forth collective knowledge learned through reflection on practice. As groups open up and become more reflective and honest about what they do and don’t know, they begin to seek data, feedback, and information from external sources; however, by definition, for a conversation to be on the left side of the arc, it must be self-directed. This means when external information of any kind—data, test scores, standards, rubrics, 360-degree feedback—is directed by another, the conversation runs the risk of moving to an imposed agenda. Often, these imposed agendas leave little room for flexibility because they are based on the needs of the stakeholder or the need to analyze third-party information. These imposed agendas can just as easily focus on test scores, rubrics, standards, or other such identified professional development programs. The inherent problem noted earlier in this book about helping is also problematic here. Often, what is imposed is neither needed nor wanted.

The key distinction here is that for conversations on the left arc, the professionals decide what data to use, when it is necessary, and how it will be applied. This does not mean they ignore outside mandates, but rather they draw on this information as a way to self-diagnose to inform their own knowing–doing–learning.

Sometimes, however, the choice is beyond the practitioners and lies with the policy-making bodies that drive educational decisions. It would be foolhardy for any educator to ignore test scores or national standards; professionals have an obligation to meet the level of proficiency of a profession. With that said, however, we believe that implementation of standards-based programs could be so much better.

There is nothing inherently wrong with other imposed professional development programs; the problem lies in the failure to understand that reflective practices with others are what build knowledge and skill. A major problem for schools is that professional development time is limited; hence, teachers experience little ongoing support for implementation of the myriad of programs pushed down to them. This means that teachers rarely engage in conversations about what they are learning from practice about any new program. To find knowledge coherence that leads to knowledge legacies, learners must articulate and evaluate their own learning trajectory.

Once again the key is the conversation, and as we move to the top of the arc, we advocate for Calibrating Conversations. A calibrating conversation is one in which both the leaders and the stakeholders weigh in on the new information and make some determinations about what would best meet all the stakeholders’ needs. The beauty of this type of conversation is that the catalyst or coach does not make the judgments; the judgments come from the stakeholders or a third-party information source. Once the data are clear, any of the conversations to the left of the arc could be used to self-analyze and act on the data. Consider the power of these questions from previously introduced conversations to help another person examine the data:

- Reflective Practice: Based on this data, how are you now reflecting upon your actions (teaching)?

- Humble Inquiry: How is this data informing your view about what is going on?

- Cognitive Coaching: Based on the data, how are you anticipating about changing some behaviors, and how do you plan to take action?

- SCARF: What do you anticipate will be most challenging for yourself and for the group when considering the changes implied in the data? (Listen for underlying SCARF behaviors.)

It is important to note here that many educators offer conversational maps for data-focused conversations. We favor the work of our colleagues Laura Lipton and Bruce Wellman at www.miravia.com. They offer training in a myriad of processes for conducting learning-focused conversations that rely on data. They draw from their deep knowledge of Cognitive Coaching and Adaptive Schools to create robust training programs, and their work supports and enhances our work. We refer the reader to them to learn more about this type of conversation.

For this book, we decided to pick a conversation that lives outside of education—Stakeholder Centered Coaching—and to introduce it as a calibrating conversation. We did this for two reasons. First, too much of the data-centered work has focused on testing and data analysis, which, while necessary, also impedes professional learning. Second, we realized that stakeholder data are powerful catalysts for change and should be a much larger part of how we bring about change in schools. While we do not address it here, getting feedback from students, as some schools are now doing, would be another powerful strategy to bring about change through stakeholder input.