Images of the grand hunting safari, complete with an entourage of porters, still abound in Tanzania, immortalised by the adventures of glamorous big-game hunters such as Ernest Hemingway. Today, it is photographic rather than hunting safaris that form the mainstay of Tanzanian tourism, but the origins of both may be found in far more ancient interaction between humans and wildlife.

African elephants, Ngorongoro Crater.

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Apa Publications

Food or commerce?

It was probably man’s urge to hunt that led to the very first development of tools, from scrapers used to skin an animal to arrowheads for shooting them. Some of the early rock-art sites scattered around Tanzania depict men hunting. A few scattered groups of nomadic hunter-gatherers still exist around the margins of Tanzania’s Lake Eyasi, southwest of Ngorongoro. Retaining an intimate knowledge of their environment and hunting terrain, the nomadic Hadza (for more information, click here) use different plant poisons to lethal effect on their poison arrows, and employ agility and cunning in the hunt. They are skilled trackers, reading game trails like a map, but will also use certain trees as a lookout point. At times they will even imitate an animal as part of the chase, for example, donning a headdress of impala horns when stalking impala.

Other tribal groups, such as the pastoralist Maasai, have co-existed in harmony with the wildlife over the years, referring to them as their second cattle, and only resorting to hunting for food in times of severe hardship. Yet traditionally, a young Maasai moran (warrior) had to kill a lion as part of the ritual to attaining manhood and status, although this is no longer a prerequisite.

The ivory trade stretches back to the days of ancient Rome. Arab caravans were certainly operating from the 7th century. By the time the British arrived, the slaughter of elephants for their ivory had become part of a sophisticated trading network, with the ivory transported to the coast by slaves the traders had captured en route.

Tourists watching a herd of buffalo, Mikumi National Park.

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Apa Publications

The Arabs supplied guns to the African hunters, and it is estimated that 30,000 elephants were being killed a year in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania in the 1850s. By the 1880s, this had risen to between 60,000 and 70,000.

Trophy hunting

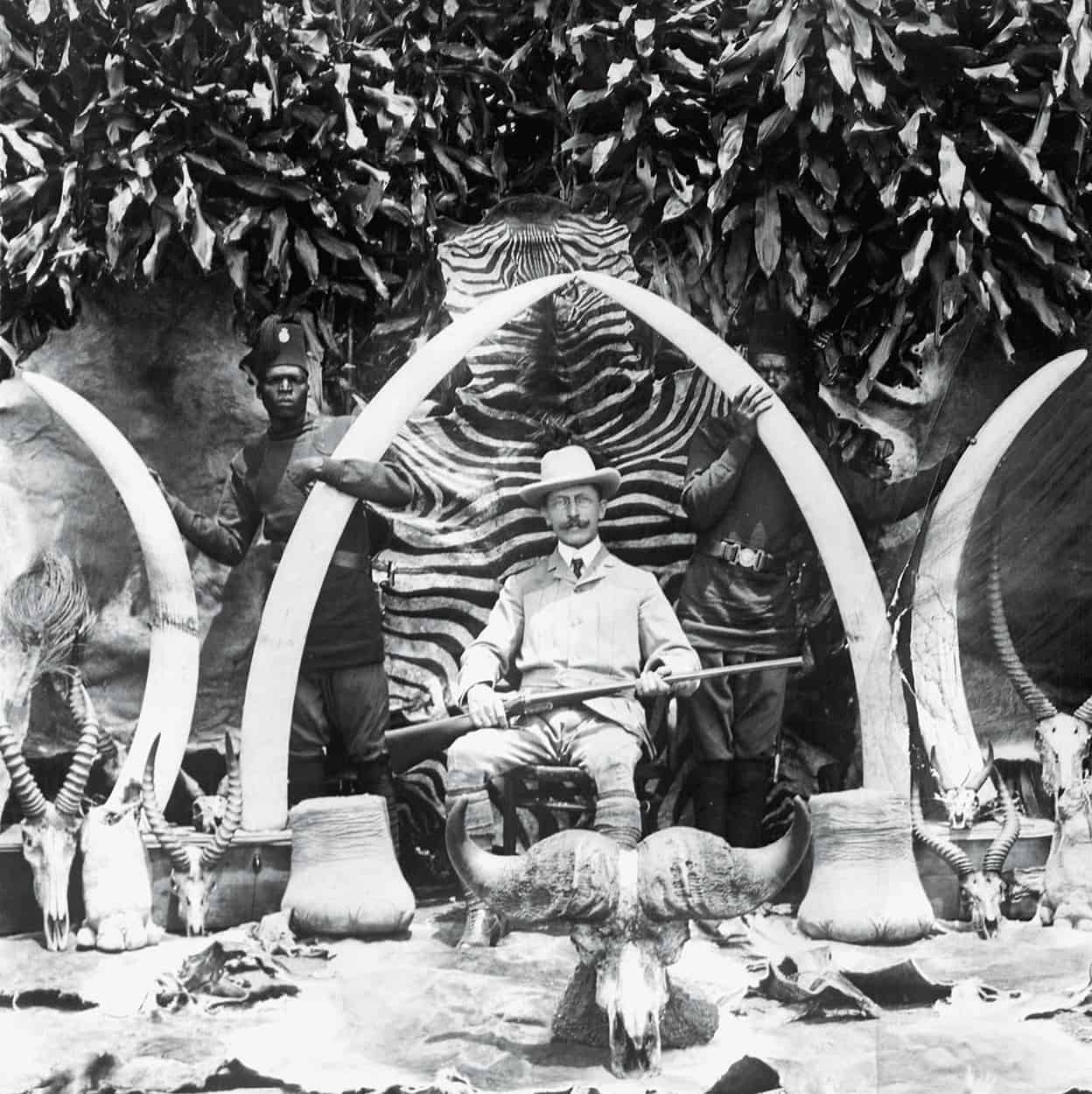

The advent of trophy hunting started with the Victorian big-game hunters, who moved up from southern Africa where much of the game had been decimated, lured by the big tuskers and large herds of East Africa.

In 1902, Frederick Courteney Selous made his first expedition to East Africa. In 1909, he returned to set up a hunting expedition for the American President, Theodore Roosevelt. The scale of this safari, to collect specimens for the Smithsonian and American Museum of Natural History in New York, took on epic proportions, and covered a nine-month period and four countries. The attendant press entourage gave international publicity to African safaris, initiating the beginning of the commercial hunting safari in Africa. Meanwhile, Selous himself made the transition from hunter to safari guide, and began, through his writings, to influence world opinion on the need to conserve wildlife.

Trophies were a large part of the testosterone-fuelled pleasures of big-game hunting.

Corbis

Great white hunter

The commercial hunting safari was thus established. For the most part, however, the professional hunters were men who appreciated the wildlife, revelled in the excitement of the bush, and simply took hunting clients to earn a living. Unfortunately, they were often too efficient. The pioneering pilot, Beryl Markham, tells of watching the elephants gather round the big tuskers to hide them from her spotter plane.

Meanwhile, these romantically rugged figures became further glamorised and embellished by movies like King Solomon’s Mines, filmed in the 1950s, the writings of hunting fanatic Ernest Hemingway, and the filming of The Snows of Kilimanjaro, also in the 1950s. White hunters became enveloped in the mantle of Hollywood.

Selous was by no means the only hunter to become an ardent conservationist. Another was Constantine Ionides, more renowned for his passion for snakes, who gives an interesting account of the early hunting days in his autobiography, A Hunter’s Story.

Drawn to Tanzania by a passion for hunting, he joined the 6th King’s African Rifles, arriving in 1925. After a short spell in the army, he turned to hunting and poaching elephants, where he was not averse to bribing chiefs and officials when in pursuit of big ivory. Ionides then worked as a white hunter, taking hunting safaris, where the emphasis was on tracking the game and finding suitable specimen trophies for the client, without the frills of drinks on ice and gourmet cuisine. He aptly described the development of the role of the white hunter today as combining the social skills of a travelling hotel manager with those of a hunter.

From the 1920s onwards, land had been set aside for Game Parks and Reserves. Ionides joined the Game Department in 1933; at that time, six European game rangers and around 120 African scouts were responsible for the entire country. Their remit was to conserve the game, protect human life and property from attacks by wildlife, and control hunting.

Safari vehicle with Burchell’s zebra, Serengeti National Park.

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Apa Publications

The modern hunt

Apart from a seven-year period from 1973 when a complete moratorium was imposed, the hunting safari has been a highly profitable industry for Tanzania. Licensed hunting began in 1984, when the government issued 10 hunting concessions through the Tanzania Wildlife Corporation (TAWICO), which was subsequently privatised. The Game Department is the government arm responsible for controlling hunting, issuing hunting concessions and regulating game quotas. The industry strives to maintain high ethical standards, although its very existence remains controversial. In the words of one operator: ‘We are committed to maintaining a long tradition of ethical hunting, and not merely providing opportunity for indiscriminate killing of animals.’

Today, wildlife areas – National Parks, National Reserves, Game Controlled Areas and Wildlife Management Areas – account for a massive 25 percent of Tanzania.

The annual hunting season runs from 1 July to 31 December. Restrictions on certain species are laid down by the international monitoring agency, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Hunting is big business – overseas clients hunting buffalo, elephants, lions and leopards pay thousands of dollars for the privilege. The government gains more than US$20 million a year in trophy fees and other associated fees. Additional money is paid to local communities, and there are significant tips for the trackers.

Photographic safaris

The development of the photographic safari derived from the hunting safaris, replacing the gun with the camera and attracting an increasing number of tourists on different budgets. The big five of the photographic safari are still those that were the prime hunting trophies in the past – elephant, lion, leopard, buffalo and rhino – though this list is supplemented by other charismatic creatures such as cheetahs, giraffe, African hunting dogs and zebra.

While some companies retain the classic style of the traditional mobile camp complete with gourmet catering, others operate a less lavish set-up, with basic camping facilities. Increasingly, new types of permanent and sophisticated accommodation have appeared, from the permanent tented camp to lodges and opulent hotels decked out in a 1930s theme. Books have been written on safari style, catering for a new fashion of Western tourist, reinventing the romantic notions conjured up by Hollywood, where accommodation has become as important as the wildlife.

Camping in comfort

The classic tented safari has its origins in the camps of the early hunters, where camping in the bush did not mean stinting on luxury. A typical safari involved dozens of porters, gun-bearers and servants. People would dress for dinner, dine off fine china and drink from crystal. Karen Blixen’s lover, Denys Finch Hatton, was remembered for taking his wind-up gramophone on safari. When Sir Winston Churchill’s father went to Africa at the end of the 19th century, a piano was considered an essential item to his wellbeing in the bush. Nor were they all-male affairs. Women would go, and sometimes shoot, in full Victorian dress.

While the National Parks are all dedicated to photographic safaris, in the Game Reserves and Wildlife Management Areas, certain lands are allocated as hunting zones. With the advent of walking safaris in the community lands adjacent to the parks in northern Tanzania, there has been a conflict of interests between the operators of hunting and photographic safaris, giving rise to a need for more stringent zoning of activities and, quite possibly, for buffer zones between them. Not only do many photographic tourists dislike the whole concept of hunting, but the proximity of guns makes the animals infinitely less approachable. Those looking for good pictures are likely to be very disappointed.

The role hunting plays in wildlife conservation is a contentious issue, especially among those who are against hunting in any shape or form. But whatever your personal views, there is no doubt that in Tanzania it brings in vital revenue which can be ploughed back into conservation projects. This is particularly the case in the vast Selous Game Reserve, which derives as much as 80 percent of its official revenue from trophy hunters. In addition, many hunting companies are affiliated to non-governmental organisations that assist the Tanzanian government with anti-poaching measures and use sustainable hunting to provide tangible economic benefits to the local communities.

A government bonfire of animal products captured from poachers and illegal traders.

Corbis

Enjoying sundowner drinks at a game reserve.

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Apa Publications

Community involvement

An interesting phenomenon is that both hunting and photographic safaris have increasingly become involved with the local communities. Quite rightly, some of the revenue received from hunting and photographic tourism is ploughed back into community development, building schools, providing bursaries for education, health care and water points.

On walking safaris in Maasai areas, tourists are guided by the Maasai, learning about the environment and the traditional uses of plants, as well as glimpsing Maasai culture at first hand. With the hunting safaris, local people are employed as trackers, and meat is distributed to neighbouring villages. This has resulted in a shift in the attitude of local people from seeing wildlife as a pest to valuing it as a resource.

Maasai giraffe on a walking safari near Lake Manyara.

Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Apa Publications

Poaching

During the 1970s and ’80s, as elsewhere in Africa, Tanzania’s elephant population was decimated in the ivory wars. Some herds were poached to within 20 percent of their former size. At its worst, in the Selous Game Reserve, 20,000 elephants were slaughtered over a two-year period. Poaching was out of control, and the government did not have the resources to combat it. The timing coincided with the anti-hunting ban in Tanzania, giving the poachers carte blanche in the hunting areas.

Fortunately, the international outcry resulted in the CITES imposing a moratorium on the ivory trade in 1989, when the African elephant was placed on the critical endangered species list, which gave a total ban on trading in elephant products. In late 2002, a limited trade in ivory resumed. There was no immediate increase in poaching as a result of this, but numerous reports indicate that elephant poaching throughout Tanzania has been on the increase since 2009. In 2016, the WWF warned that elephants could disappear from the Selous Game Reserve completely by 2022 unless poaching is stopped.

On the endangered list

The current situation with black rhino is more fragile. It is estimated that there are only a few dozen animals in the Selous, and they constitute about two-thirds of Tanzania’s total rhino population (the remainder being split between the Ngorongoro Crater and a few specific parts of the Serengeti). The population is so fragmented and dispersed that there have been suggestions that the only way to create a viable breeding pool is to create a sanctuary within the Selous.

In 1994, the Sand Rivers Rhino Project was established by Richard Bonham and the late Elizabeth Theobold to protect rhinos from poaching. The project, now named the Selous Rhino Trust, has grown in scale and received major funding from the European Union.

The rhino are difficult to see, a reflection of poaching avoidance and the dense, riverine gullies in which they live. Trackers with global positioning systems (GPS) have only a 50 percent chance of finding rhino evidence along a 1,000km (620-mile) transect.

Since the carnage of the 1970s and ’80s, poaching remains a problem, but it is not on the same gross scale as before. The battle continues nevertheless, and in 2017 the government launched plans to create a paramilitary force to target poachers. At the same time, there has been an increase in the local bush-meat trade, particularly of smaller species such as antelope, where the indiscriminate killing gives great cause for concern. Undoubtedly, the future of Tanzania’s wildlife remains balanced in the hands of man.