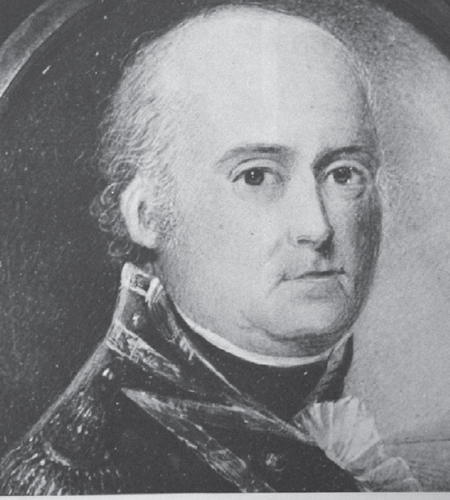

John Macarthur, the previous paymaster from whom William bought Brush Farm in 1800 (Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW [DG 242])

3 The Second Largest Landowner in Two Years, Bankrupt in Three

After William bought Brush Farm from John Macarthur in January 1800 he launched into a land buying spree which would make him the second largest landholder New South Wales within two years – and bankrupt him in three. The view he had of Port Jackson when the Minerva dropped anchor on 11 January 1800 is worth conjuring up for its differences from the Sydney landscape of today. The Circular Quay did not exist. The Tank Stream flowed down into Sydney Cove with its cargo of detritus, the indigenous vegetation of its valley already gone, while on the right was the jumble of primitive housing on the Rocks, where there was a disregarded midden of the remains of the Eora peoples’ fish meals. As Grace Karskens points out, the houses on the Rocks, one- or two-roomed huts of wattle and clay with thatched roofs, were possibly introduced by rural convicts in a vernacular style. ‘Convicts and soldiers chose sites in their respective zones, built houses and soon regarded them as their own.’1 The main street was the High Street (later George Street). Governor Macquarie’s regimented town planning was more than a decade ahead.

William and his family, one may assume, were met and probably taken direct by boat to Parramatta. The river was the preferred means of getting to the settlement, partly because of the danger of attacks by Aborigines, partly because of dangers from gangs of escaped convicts. The entrance to the Parramatta River passed the tip of the Rocks and the Dawes Point battery, where the harbour bridge spans it today. A painting of the landing place as it was in 1809, now in the Mitchell Library, helps to give an idea of the landscape. Major Grose had built a store on the south bank and there were early houses on the right. The mangroves which now line so much of the river bank had not yet grown. At Parramatta itself the Corps had a barracks, close by the original military redoubt, where Macarthur had established the paymaster’s office. Parramatta was an Aboriginal word meaning ‘head of a river’, which Governor Phillip had adopted after he recognized it was a more promising place for a settlement than Sydney Cove.

John Macarthur, the previous paymaster from whom William bought Brush Farm in 1800 (Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW [DG 242])

Port Jackson as seen by the surgeon of the Minerva in January 1800 (British Library Mss 13880)

By November 1791 Phillip had abandoned agricultural efforts at Sydney in favour of the fertile land round Parramatta and established a farm at what he named Rose Hill. He then decided to lay down a township west of the redoubt, between it and Government House, first constructed by him in 1793 as a very simple building. Only later did it become the elegant building which still overlooks the centre of the conurbation. Parramatta being situated 24 kilometres from Sydney by land, further by river, it was never the seat of the Governor’s main residence, nor of the New South Wales Corps’ principal barracks. Those were in Sydney, between what Macquarie named George Street and York Street, bounded at one end of King Street. Today’s Wynyard Square occupies part of the substantial site and the short Barrack Street led to it. It was from there that Major Johnston marched his men overnight to deal with the Castle Hill (or Vinegar Hill) convict uprising in 1804.

In terms of the acquisition of land by officers, Parramatta was far more important than anywhere else in the early days. On 25 February 1793 acting Governor Grose gave John Macarthur, who was administering the settlement there, a grant of 100 acres and a further 100 a year later. This became Elizabeth Farm, named after John’s wife. The house is still there today, on land running down to the river. Gradually officers obtained plots of land in the developing town, or near it. William’s purchase of Brush Farm fitted into a regimental pattern at the settlement, although it was further out in what is now Ryde. The name Brush Farm derived from the patches of local rainforest, or ‘brush’, surrounding the upper areas of The Ponds. The present day Brush Farm house was not where William and Rebecca lived. It was originally Joseph Holt’s house, greatly extended and glorified by Gregory Blaxland, who owned it from 1807.2 If the surgeon Price’s watercolour of Mr Cox’s ‘box’ is correct, William’s own house was much closer to the water. From here he would have ridden on horseback to the paymaster’s office in the barracks. The family evidently rode, since Holt described how in 1803 he found Rebecca had no horse at her disposal after the bankruptcy, when they were still living at Brush Farm.

A woman of New South Wales and an officer of the NSW Corps at Parramatta when William was there (Juan Ravenet, published Paris 1824)

A map drawn in 1804 by the colonial surveyor, George Evans, shows how Parramatta was laid out. The eastern end of the High Street, now George Street, was the barracks, originally called the Redoubt. Facing it at the western end was Government House in its domain on a low hill. The gaol stood a way to the north and the hospital a little closer in, by the oxbow lake known as the Crescent. Directly between Government House and the barracks, lining the 205 foot wide High Street, were the thatched homes of the officers and officials mentioned earlier, on small rectangular plots of land. Some of their owners were to feature largely in William’s future life, notably Captain John Piper, John Brabyn, Edward Abbott and D’Arcy Wentworth. The contrast between how some lived then and how they lived later is seen at an extreme in the case of John Piper, William’s particular friend. Piper later made a great deal of money as the Naval Officer at Sydney, collecting customs duties, and in 1822 completed the magnificent mansion Henrietta Villa at Point Piper on the Sydney foreshore, only to be bankrupted in 1827.

The historian Michael Roe comments that ‘The oldest established [gentry] could trace their colonial roots to the first twenty years of Australian history – to the officers of the military establishment … or the civil establishment’.3 Among the civilians was that unusual character, the chaplain Samuel Marsden, the sturdy son of a Yorkshire blacksmith who became notorious for devoting as much time to his four-legged flock as to his parochial one. The pumpkin-faced Marsden resided close to the simple church at Parramatta which is today St John’s Cathedral, where William’s second marriage took place in 1821. He later had a grandiose Georgian rectory built for himself.

Samuel Marsden, chaplain, pastoralist and magistrate, conducted William’s second marriage (Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand)

Parramatta was thus the focal point of William Cox’s first years in the colony. Early sketches show the convicts’ huts, cultivated fields, farm carts, Aborigines and women walking down the High Street. It was a small community where everyone – excluding the convicts – knew everyone else and where William rapidly became prominent. His experiences illustrate the strong position the New South Wales Corps’ officers held in acquiring estates in the 1790s and 1800s (a strength totally demolished when Governor Macquarie was ordered to send the regiment home in 1810). As John Macarthur’s wife, Elizabeth, had told a friend back in 1790 – only two years after the landing of the First Fleet – ‘This country offers numerous advantages to persons holding appointments under government’.4 That also presaged the ways by which William, and such of his contemporaries as John Macarthur, acquired grazing land on a large scale and created great estates. It can bear repeating that they had brought with them the overriding lesson from late eighteenth-century England that the ownership of land spelt wealth and power. They relatively quickly turned themselves into a dominant class of landed gentry in the colony, roughly between the governorates of King and Bourke.

Since Elizabeth Macarthur was telling friends about the opportunities in the colony eight years before William transferred into the Corps it is reasonable to assume that he knew all about them in advance, even if he may not have made the 1797 visit. As it was, the early years were for him a sorry saga of the eighteenth-century style chicanery thought acceptable at the time – ambition, opportunism and a quite extraordinary degree of naiveté. The opportunism is illustrated by William unhesitatingly using regimental funds to buy land, as recorded by Joseph Holt and eventually realized by the army authorities at home.

Although the Colonial Secretary’s correspondence and the Historical Records of Australia yield bare facts about William’s acquisitions, while the Sydney Gazette published sale notices, most of the knowledge of the early days at Brush Farm derives from Holt’s Memoirs. At the outset, on 22 January 1800, William had told him: ‘I have money, and you are possessed of considerable knowledge in agricultural pursuits; suppose we join them together, I think we should easily make a fortune’.5 Given that William’s main civilian experience was of clockmaking, and Holt had been a successful farmer in Ireland, this was a prudent move.6 The terms of the deal were not instantly agreed. Holt refused a salary on the grounds that he had been a master all his life and had ‘great reluctance to become a servant’. In the end they had no written arrangement, Holt being satisfied that he would receive a fair remuneration, which William called ‘a hard bargain’.7

Holt continued to work as William’s farm manager through to April 1804, long after the bankruptcy, and continued to keep in touch with William, as a letter from William to Governor King of 24 December 1804 shows. In this letter William recounted how Holt had warned him of a planned uprising by English convicts, including some of his own workers.8 Holt and William also had their quarrels. One such occasion was in October 1800 when Holt, who as a former Irish rebel was held under constant suspicion by officials, was not – in his view – adequately defended by Cox against accusations. After they had made things up, Holt and his wife went home and ‘had scarcely got into our house before the servant arrived with a basket, and a note from Mrs Cox; in the basket were two gallons of wine and two of rum, which the good lady begged us to accept’. This is one of the few recorded examples of Rebecca’s actions in running the Cox household and illustrates her practicality in immediately making amends for her husband’s mistakes plus an instinctive generosity.9

Macarthur sold Brush Farm at Dundas because he was thinking of returning to England. William is highly likely to have known this, not least because he was taking over the job which Macarthur previously held. Holt described it vividly: ‘I had never seen such mould as it was, for it resembled an old churchyard; loose black rank looking earth’. However, the ground was ‘very well situated and I gave my opinion very much in favour of the purchase’. Holt moved his family there on 1 February 1800 and immediately ‘prepared sixty acres to be sown in with wheat’. He relates how Macarthur cheated William by selling him ‘a large flock of sheep … They were old rotten ewes of the Bengal breed; he paid three pounds each for them and one hundred and fifty pounds for a brood mare.’ Given that William had been a clockmaker, it is hardly surprising that he was fooled. Holt later described Macarthur as a ‘very overbearing and tyrannical man’.10

By contrast to Macarthur, who he condemned, Holt considered ‘Captain Cox was a man of strict integrity … But whatever Mr McArthur thought, he [i.e., Macarthur] did not act in this affair in a gentleman like manner’.11 This is an interesting reflection, given the nature of Cox’s land dealings and of Macarthur becoming pre-eminent among the colonial landed gentry. It incidentally shows that William must have had considerable sums of cash with him when he arrived, at least partly from his dealings in Rio, and probably also from having sold the Devizes house.

Whether his first flock was rotten or not, by November 1802 the Agricultural Returns for the colony show Cox as owning 1440 acres and 1100 sheep – as many as Macarthur, who had now left the army. The officers often took over small acreages from ex-soldiers, persuading them to exchange their land for goods or for spirits. The practice was bemoaned by Governor King, who castigated the ‘few monopolizing traders … not failing to ruin those they marked for their prey by the baneful lure of spirits’.12 King regarded the practice as morally dubious, despite the lax standards of such actions of his own as later exchanging grants of land with his successor, Bligh.

Although William Cox was not guilty of such trading, his attempts to build an agricultural empire in a hurry seem to have been rooted in an eighteenth-century view of the perquisites of office. There was a huge advantage in being able to offer bills drawn on the regimental agents, as they were payable in sterling, which did not circulate in the colony and was much sought after. Most payments were made with promissory notes. Looked at from almost any perspective, two aspects of the colony’s initial planning were extraordinary. One was that the authorities did not envisage the need for a form of legal currency. The other was that they do not seem to have appreciated how by bringing out female convicts along with men, they were guaranteeing a next generation of free-born British citizens. The effect of this will be seen in later chapters.

Once he had bought Brush Farm, William quickly went on to acquire a highly productive fruit farm adjoining it. This was the 600 acre Canterbury Farm, belonging to the Reverend Richard Johnson, a Church of England clergyman who had brought orange seeds from Rio de Janeiro and also grew nectarines, peaches and apricots, as well as having planted two acres of vines. Having made his fortune he was leaving the colony. William promptly built a road connecting the two farms, along the line of the Kissing Point road, started to build a ‘large dwelling house’ and continued to expand his holdings.13 Holt lists a considerable number of other small land purchases from individuals, a selection of which illustrate how the 1440 acres were accumulated in an almost ravenous way.

Holt comments on his own astuteness when he ‘made a good bargain for Mr Cox, clearing for him above £1,000 in one year by these purchases’.14 Two such were of 30 acres from Thomas Higgins for £35 and of 50 acres from Mr Hume for £45. They bought John Ramsey’s farm of 75 acres for £60, Berrington’s 25 acres for £100, and 100 acres from Captain McKellar ‘for £50 and ten gallons of rum’, as well as smaller properties which may have belonged to ex-soldiers. Holt again records, with a note of triumph, how they acquired a 100 acre farm from a Dr Thompson, with 124 sheep and paid £500 for it, as usual with bills drawn on the regimental agents. The accompanying stock was, in the words quoted at the head of the Foreword, ‘worth twenty five percent more than the purchase money … Mr Cox paid him with bills on the regimental agents.’

This particular deal had a less than happy ending for the seller, but provides a description of Cox’s farms. Dr Thompson’s wife deserted him for an officer on the French ship on which they left, taking the bills of exchange with her. The ship was one of two corvettes (Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste) sent out by Napoleon Buonaparte to survey the coast of Australia. The French naturalist, Peron, who travelled with them, visited Brush Farm in 1802 and was highly complimentary about it. His subsequent book described the farm in a way no one else did:

Often on the summit of a picturesque hillock may be a discerned a large and elegant mansion, surrounded by more considerable cultivated lands and covered by greater numbers of flocks and labourers … The one in question belonged to Mr Cox … As soon as he perceived M. Bellefin and me, he got into a boat belonging to his farm and, coming to our vessel invited us in so pressing a manner to pass the night at his house that we could not resist his friendly solicitations … On a second voyage which I made to his estate [with Colonel Paterson and Mr Laycock] Mr Cox took us all to dinner to another farm, still more rich and elegant … more inland on the side of Castle Hill … The road which leads from one to the other of these farms is so wide and convenient that we went over it in a carriage. It is between six and seven miles in length and to make it immense loads of rubbish were necessary. The whole of Mr Cox’s land amounts to 860 acres … [with] 800 sheep of the finest breeds.15

The second farm was clearly Canterbury, the inclusion of which in the estate increased Holt’s daily ride of inspection to about 12 miles along the line of the Kissing Point road. The house, which so impressed Peron, must have been ‘the handsome place’ which Holt describes William as having wished to build. Perhaps the most telling point in Peron’s narrative is that he was taken to see Cox’s properties by Colonel Paterson (the commanding officer of the New South Wales Corps) and his lady. Paterson was evidently showing off how advanced the colony had become to this French naturalist. He would later be criticized for condoning Cox’s venality.

Holt and Cox bought stock again from Macarthur despite the rotten ewes, including ‘one hundred head of cattle, bulls and cows’ and 69 pigs. Holt cannily ‘advised Mr Cox to take a bottle or two of wine with him, and then to make the bargain after dinner’. The Irishman had a great belief in using liquor to facilitate dealings, as he later showed when the bankruptcy sales took place. Whether because of the alcoholic influence or not, William only had to pay £500 down for the cattle, on the basis that the stock would later be divided. When that happened they had so multiplied that Holt cleared a £1200 profit for William on the deal. ‘So,’ Holt recorded with satisfaction, ‘we made up the loss he had sustained by the manoeuvres of the first bargain.’ There was an attractive deviousness about Holt. Not all their offers were successful, however. On 14 May 1802 William made a credit offer for Major Foveaux’s farm and stock, but was outbid by a Lieutenant Rowley’s cash offer of £700. In 1800 Foveaux had been the largest landowner in the colony, was an important officer in the Corps and may have been wary of William’s land deals, yet not willing – like Paterson – to denounce the use of bills drawn on the regimental agents. The officers were almost endemically corrupt.16

Holt also describes how he set about planting William’s land. At the outset, in February 1800, he had prepared 60 acres to be planted with wheat and began sowing the seed on 24 March, finishing on 3 June. In October he planted Indian corn.17 This was all done by hoeing between the tree stumps, which in the early days were not dug up when the ground was cleared, making it impractical to use ploughs (although Macarthur had imported the first iron plough in 1794). All farming involved the employment of assigned convicts. In the same year of 1800 Holt was appalled when forced to witness the flogging of an Irish convict named Fitzgerald at Toongabbie, who had been sentenced to 300 lashes. During this often quoted incident, Holt wrote that the ‘flesh and skin blew off my face as they shook off the cats [cat o’ nine tails]’. He commented that this flogging took place although ‘it was against the law to flog a man past fifty lashes without a doctor’.18 Holt then had a seven pound hoe made, which he required labourers working for him to use, instead of being flogged, and called it his personal flogger, also a much quoted remark. On William seeing it ‘Mr Cox said “this is a terrible tool”’.19

The background to any agricultural enterprise was always that settlers had to learn how to farm in completely unfamiliar territory with strange vegetation, where land could, in Holt’s words ‘require labour and manure as much as the mountains of Wicklow; but [with the benefit that] every district yields two crops a year’.20 Even so, the climate was often hostile. Drought could alternate with flood, and army worm could devastate crops almost overnight. Thus on 14 October of William’s first year a hailstorm destroyed every acre of the wheat Holt had so laboriously planted. A worse disaster struck on 21 October 1803, when their harvest was attacked by the blight known as rust. The Memoirs say that 266 acres of his wheat were completely lost in three days and the produce of those acres was not worth £20.21 Farming would also involve a problem that Holt did not have to encounter, but which William later did on the Hawkesbury in 1816 and at Bathurst in 1824, namely the increasing displacement of Aboriginal people, with resultant violent conflict.

The way in which William built up this estate needs to be set in the context of the widespread misuse of regimental funds. The military historian Anthony Clayton, reviewing officers’ public morals at that time, writes that from the seventeenth century onward ‘Officers were all as much preoccupied with the business side of their lives as the professional’. This did not cease until the Victorian era. In William’s time the essential corruption of the whole system continued to enable officers both at home and overseas to supplement their income in such dubious, but usually legal, ways as ‘managing regimental funds’.22 The New South Wales Corps officers were particularly adept at this. Between 1792 and 1798 they had invested £36,844 of regimental funds in their own enterprises.23 Even the relatively more scrupulous Macquarie, when a newly married captain, paid to take on the army paymastership in Bombay in 1795 so that he could draw the regiment’s pay three to five months in advance and invest it short-term with Arab money lenders.24 William’s mistake was to invest in the illiquid asset of land.

In parallel with this, William was taking a serious risk by disregarding new official regulations rescinding permission for officers to farm actively, ordered by the Commander in Chief, HRH the Duke of York, the brother of George III, in 1802. This was done at the urging of the Duke of Portland, who had become aware that in 1800 Macarthur owned 1300 acres, in spite of being a serving officer.25 Macarthur escaped the ban, because he had been sent home for court martial by Governor King in 1801, after fighting a duel with Lieutenant Colonel Paterson (the trial was aborted for lack of evidence) and was allowed to leave the army. But William was caught by the prohibition. As a result, his first appointment as a magistrate (at Parramatta), made on 6 January 1802, was cancelled on 5 October that same year by King, who as a naval officer neither could nor would tolerate the disobedience of orders. Cox rashly continued to disregard the prohibition and the whole question of failure to obey orders eventually became a more serious disciplinary matter than the ‘malversation’ of the regimental funds.

The historical backdrop to the acquisition of land by officers went back almost to the first days of the colony. Originally Governor Phillip had made few land grants. Samuel Bennett remarks that whereas at the time of his departure not much more than 3000 acres had been allotted, in a short period afterwards the officers secured 15,000 acres for themselves.26 This was thanks to Major Francis Grose. When serving as lieutenant governor in 1792–95, after Phillip’s departure, Grose freely gave land grants to his officers. Another commentator remarks that under Grose ‘the spirit of commercialism and the desire to obtain landed estates became the principal motives in life with many officers of the New South Wales Corps’.27 It was no coincidence that in the early 1800s the largest landowner was Quartermaster Laycock with 1470 acres. He and William were the two officers best placed to profit from their official positions.

This heyday of the officers in obtaining land ended with the Bligh Rebellion and the arrival of Macquarie as governor, although during that period of army rule Lieutenant Colonel Paterson made grants of some 67,000 acres, a small one being at Mulgoa to Rebecca Cox for her four-year-old son, Edward – a grant which she later had to ask Macquarie to ratify.28 Not that the officers had been alone in acquiring land. On a lower level the first free emigrants who arrived on 16 January 1793 on the Bellona were given free passages and land grants, tools, two years’ provisions and convict labour by government.29 However, during that decade the landed interests of the officer class – including officials – became paramount.

A considerable change in official policy took place during the first decade of the new century, benefiting only a few gentleman settlers, but allocating much larger acreages to them. The idea originated from the surgeon William Balmain, a friend of Governor Hunter, who suggested to Lord Camden, the Secretary of State, that he should send out gentlemen settlers who could form an élite. The first beneficiaries were John Macarthur (5000 acres) and Walter Davidson the son of the Prince Regent’s physician (2000 acres). Their grants were on the Cowpastures, an area of excellent grazing on the south-west of the Cumberland Plain, where a herd of cattle had long before strayed, gone wild and greatly multiplied. It was hoped, ultimately in vain, that the herd could be domesticated again. The grants of land were to be ‘fit for the pasture of sheep … in perpetuity, with the usual reserve of quit rent to the Crown’. Macarthur was also to be ‘indulged with a reasonable number of convicts … for the purpose of attending to his sheep’. He would pay for their maintenance and so ‘a saving will accrue to the Government’.30

Governor King was opposed to this plan, avowedly because of the hope of domesticating the wild cattle. Additionally, the serving governor had an interest in the herd because he had a share in it.31 King intensely disliked Macarthur, whom he had called ‘The Great Perturbator’ on account of the trouble he had caused. But an order from the Colonial Secretary could not be refused. Whilst acknowledging the value to the colony of Macarthur’s sheep breeding, King managed to delay the grant’s execution. Nonetheless, in the end the whole area became Macarthur’s Camden Park.

Lord Camden’s instruction was an historic turning point in the rise of the pastoralists. The 5000 acres was the largest grant ever given in the colony. Thereafter, directions were given to governors by secretaries of state to make land grants to favoured settlers, to allocate them convict labour and, to a lesser extent, to give them cattle. In 1806 grants totalling 12,000 acres were ordered by William Windham, as Secretary of State, for two gentleman farmers from Kent, John and Gregory Blaxland, who were selling up to emigrate.32 King expressed disappointment that, although the brothers had brought out seed, they claimed it had rotted on the voyage and refused to attempt planting it, insisting instead that they should buy 1700 breeding stock from the government herds.33 Cattle rearing on broad acres would have looked more like a gentleman’s occupation than growing crops. King himself was realistically concerned about having sufficient agricultural production to feed the growing population, but had to obey. Thus 1806 can be set as a date for the recognition of the landed gentry in New South Wales. By this time William Cox was bankrupt and waiting to be sent home for trial.34

William’s whole edifice of debt had collapsed when, in January 1803, he had a quarrel with Dr Jamison, the Surgeon General, to whom he owed £200. ‘In February Dr Jamison pressed him for the money,’ Holt records. ‘The sum itself was a trifle to pay; but the doctor had circulated a report that Mr Cox had failed, which made everyone who had the slightest demand upon him press forward with their claims at once … they made no less a sum than twenty two thousand pounds.’35 Ironically, this doctor was the father of Sir John Jamison, with whom William was to have a close political and cultural relationship in the 1820s. In spite of maintaining that his debtors owed him enough to cover his position, William was unable to stall the creditors, who foreclosed.

The exact wording of these bills of exchange issued by William is shown by one he gave to Robert Campbell, a leading Sydney merchant and trader, in the same month that the creditors foreclosed. It read:

Ninety days after sight Pay this my First Bill of Exchange, Second and Third same Tenor and Date unpaid unto Robert Campbell Esq for one thousand pounds and place the same to the Acct of the pay of the New South Wales Corps without or without advice from, Gentlemen, Wm Cox Paymaster

It was addressed to Messrs Cox (no relation) and Greenwood, Craig’s Court, Charing Cross. This particular bill had been presented numerous times and was ‘protested’ on 28 July 1804 by a notary ‘In Testimonium Veritatis, Thomas Bonnet, Notr Pub’, as others had been by another notary named Venn. Bonnet eventually spoke to a clerk who said the bill would not be paid.36

Since any bill had to be sent to London to be presented, it could be nine months at least before its beneficiary learnt that it had not been honoured and could take action through a London agent, in this case Bonnet, taking the time of a further voyage. Meanwhile, of course, William enjoyed the use of the thousand pounds. Between October 1801 and January 1803 William issued a total of six bills to Campbell, totalling £4717. Campbell, who then did very well out of William’s best farms, was appointed treasurer to William’s estate.

Miniature of Robert Campbell (Courtesy of Elizabeth Forbes)

The first sale was held on 15 April 1803 at Campbell’s order. On 26 May the 900 acres of Canterbury Farm were auctioned, as well as two other farms of 100 acres at Prospect Hill, a third of 94 acres ‘adjoining’ the town of Parramatta and also 1700 sheep ‘part of which are of Spanish breed’. The auctioneer was Simeon Lord (an ex-convict trader, later to become both a magistrate and a pastoralist). Holt helpfully gave everyone there plenty of rum to stimulate the bidding. But the individual plots of land fetched far less than William had paid for them. D’Arcy Wentworth, who bought five, paid only 108 guineas for 100 acres, Samuel Marsden gave 56 guineas for the Barrington (or Berrington) property which Holt had bought for William for £100.37 On 6 July household goods were sold, including ‘linens, curtains, calicos, shoes, leather, soap, tobacco, ironmongery’.38 It must have been intensely distressing for Rebecca. On 10 May 1803 Holt records ‘I found that Mrs Cox had no horse at her command. I asked if she would accept of my mare … after a pause Mrs Cox said she would accept of my very friendly offer and expressed herself greatly obliged to me. She was a complete gentlewoman.’39 Rebecca evidently displayed great fortitude, as she did again when her husband was sent home for trial and was receiving no pay.

On 11 November 1803, ‘a quantity of wheat and about 50 pigs’ were sold.40 Holt began to collect the debts due to the estate, but they were nothing like enough. From Governor King’s point of view William’s disaster had a silver lining. He reported home, on 17 September 1803, that ‘not a few [settlers] have profitted [sic] by the division of the Paymaster’s of the New South Wales Corps large stock of cattle, horses and sheep, which he had been monopolizing until he was compelled to sell them to satisfy the great debts he had accumulated in and out of the colony’.41 King was a realist and William’s disaster would have helped his aim of bringing about a wider ownership of property. His comments illustrate how significant a landowner William had become.

Simeon Lord, the ex-convict trader who auctioned William’s property in 1803 (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [MIN 92])

For whatever reason, the Governor began helping William in various practical ways. On 3 February 1804 he agreed to accept £1500 from the sale of £2000 of 3 percent stock and also to take £2949 8s 2¼d worth of Cox’s wheat into the Commissary, both of these to help liquidate the debt owed to the army agents, which it halved. There followed what seems to have been a curious manoeuvre by King to help even more, when the trustees, headed by Robert Campbell, asked if they could pay another eight to ten thousand bushels of wheat into the Commissary. This wheat had remained in store in William’s ownership, despite the forced sales. On 1 March 1804 King informed the trustees that ‘The stores are now, and will continue open for the receipt of wheat in payment of debts due to the Crown’. He emphasized that every cultivator would have an ‘equal chance’ to dispose of wheat. Since no public notification of this opportunity appeared in the Sydney Gazette in either February or March, the equal chance appears to have been deliberately non-existent, although the colony and the newspaper were much preoccupied at the time with the Castle Hill convict riots of 4 March. Even better, King gave the trustees a complete indemnity for any damages resulting from the arrangement, which he need hardly have done.42

King’s assistance had its political side. The Hawkesbury had been settled by Grose in 1794 to accommodate former soldiers and ex-convicts. King wanted to see the settlement improved, populated as it now was mainly by ex-convict smallholders, the soldiers often having been persuaded to sell their plots, usually in exchange for spirits. At the same time King was sympathetic to William, possibly because he was himself in a more or less permanent stand-off conflict with the New South Wales Corps and might have seen Cox in some way as a victim. The Governor had known when he arrived in 1800 that he would have to fight the officers and, in the words of the Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘was faced with frequent disobedience and insolence’ from them, after he refused to allow a cargo of spirits to be landed (spirits being the great trading asset of the officers).

Court martial records, not often quoted, show how King was constantly frustrated in his efforts to bring the officers to heel. He ordered the trials of a succession of officers for offences as blatant as looting a wrecked ship. The court martial records show that in at least four cases the accused men’s brother officers acquitted him. Each time King appealed to the monarch against the verdict without result.43 Additionally, officers circulated libellous ‘pipes’ (doggerel attacks) against him. One, written by Captain Anthony Fenn-Kemp, for which King accused him of sedition, read in part:

On Monday keep shop

In two hours, time to stop

To relax from such KINGLY fatigue

And rob Government more

Than a host of good theives [sic] by intrigue.

The Board of Officers felt the satire acceptable rather then seditious and honourably acquitted the captain. Whether the officers were aware of it or not, these pipes were little different to the cartoons which constantly lampooned the Prince Regent at home in England.

In the end the officers defeated King and when he eventually left in 1807 he was a sick man. But for all his faults, including what we would see today as corruption, King warmed to and befriended the young circumnavigator of Australia, Matthew Flinders, in 1802, and seems similarly to have liked William. He also gave semi-official appointments to Barrallier and Harris, officers disciplined by Paterson. He sardonically appointed Barrallier ‘King of the Mountains’, before sending him on an expedition now forgotten to explore the Blue Mountains.

Governor Philip Gidley King, who befriended Cox (State Library of New South Wales)

On 16 July 1804 King went further by granting William and his second son James, jointly, 200 acres at Mulgrave Place, near Windsor.44 This dovetailed conveniently with the founding of the Richmond Hill District as part of Mulgrave Place. It included what were to become the Macquarie towns of Richmond and Windsor (known originally as Green Hills), Pitt Town and Wilberforce. The precise location of the Coxes’ grant has been identified as having been on the south side of the Hawkesbury (Nepean) river between South Creek and Yarramundi Lagoon.45 The importance of this grant to the family, with its eight assigned convicts, can hardly be overstated. William was to call it Clarendon and the estate became the focal point of his life. Nor is ‘estate’ the wrong word. He instantly expanded the family holdings there, as is explained in an extraordinary letter from Parramatta to his friend and fellow officer John Piper at Norfolk Island on 28 July 1804.

By the Experiment was received our two dearest sons safe & well … I got them sent out as settlers (to save expence) & have got 250 acres of ground for them with 4 men, tools etc etc as other settlers have, this with my spare time assisting them will soon get them a farm, they are likewise on the store … I have no doubts of being able to get a living out of the Regiment, as well as in it.

William also said, ‘Charles is still left in England, Capt Nelson [?] of the Royal Admiral objected to his coming and said if I could not maintain him then he would [be liable]’.46

This part of the letter is not only hard to read, it is inexplicable. Charles was the third son, born in 1792, he was clearly recorded in Price’s manifest as having travelled out on the Minerva and no other mention of his staying in England was made, although the details of where William and James spent their time is known. They had been left behind at the grammar school in Salisbury and with the Dawe family.

It was James with whom William had just been given a joint grant by King, perhaps before the boy had actually arrived. William evidently also obtained one for William Jnr, these new grants adding 500 acres to the first 200, illustrating how exploitative William could be. In the 1820s he claimed that his youngest son, Edward, who had been born in the colony, was a new arrival when he returned from training in Yorkshire.

Even more oddly, the letter to Piper shows that, in spite of having been suspended as paymaster when bankrupted, and having disobeyed the C-in-C’s prohibition on farming, William expected to be able both to continue farming and remain in the army. Nor was he being paid, since the National Archives records show that in 1809 a Mr Merry, at the Office for War, was calculating what he was owed since 1803. During the intervening six years the family must have lived either off what money they had managed to keep, if any, or more probably what farm produce they could get to market. In 1809 Rebecca was obliged to ask for rations from the government store on three occasions, in February, March and July 1809.

The forced sales continued to the end of 1804, with a sale of household effects reported in the Sydney Gazette of 6 January 1805.47 Brush Farm itself was not sold until 14 January 1805, when Simeon Lord acquired it for £546 (he sold it on to Gregory Blaxland in 1807). This meant that the family were able to remain there until they established themselves on the Hawkesbury grant. The delay in putting Brush Farm on the market suggests that William was being enabled to avoid homelessness. The sale advertisement described it as being situated in the Field of Mars and ‘one of the most eligible situations for a family in this colony’. On 31 March 1805 a further dividend to creditors was announced, making a total of 75 percent.

Yet, when the sales were all over, William still owed the Army Agents £7898 16s 4½d. Furthermore, although he had paid a dividend to Robert Campbell, he was to be pursued for debt by him until 1831. In spite of having appeals rejected by first the Governor and then the Privy Council in London, Campbell persisted, refusing to recognize that by accepting the ‘dividend’ from William many years before he had invalidated his action. It was settled in William’s favour by W. C. Wentworth, whose hastily scrawled opinion was preserved in the family papers and is now in the Mitchell Library. Wentworth wrote:

It appears to me notwithstanding the decision of the former Supreme Court of Judicature in this Colony and the confirmation of that decision both by the Court of Appeal and the Privy Council in England that Mr Campbell first by receiving a divided of 15/- in the £ and next by constituting an action against Mr Cox for the recovery of the balance … on the merits of the case Mr Cox could not fail to obtain a verdict.48

This was to say William won, for which Wentworth charged five guineas. The fee was worth roughly 21 acres of farmland, at the going price of 5s per acre. Quite extraordinarily, Campbell had much earlier lost the actions when he tried to obtain payment for three other bills owed to Scott and co., of £700, £500 and £1000, on which William had paid a 15s in the pound dividend on 30 July 1809, when he was still in England. Long before Campbell’s final attempt William had paid 27s 6d in the pound on some debts. There was no explanation for Campbell’s vindictiveness, but the effect it had on William was obvious enough: he never gave up seeking the government construction contracts which gave him an income independently of farming.

By 1804 William ought to have been in a trough of despair, despite his confident letter to Piper. Most of his land had been sold, his household possessions had been sold, and his house inevitably would be. But he did have King’s 200 acre joint grants. With Rebecca’s support he began again, with the same determination which a decade later would characterize his road building through the Blue Mountains. The move represented both the nadir of his land ownership and a fresh start. From this small beginning the farm which he named Clarendon developed over the years into a major estate, although the choice of its name is a minor mystery. As was explained in Chapter 1, the Royal Park of Clarendon near Salisbury had only the most tenuous connection to the family ancestry.

When his other sons had prospered enough to build their own grand houses in the 1830s, they too called them after family-connected places in Dorset, such as Fernhill and Winbourne.49 Their father must have coached them in these antecedents. Indeed the use of the Dorset names suggests that William was consciously trying to recreate the family’s long-lost status in his new home, having lacked the money and influence to do so in England. James Cox also gave the name Clarendon to his great mansion near Launceston, in Van Diemen’s Land, in 1834.

However, all this was for the future. In the present time of 1804 what must have preyed on William’s mind was the action to be taken against him by the army. A curious light is shed on this by a letter written on 9 November 1803 by John Macarthur, now out of the army and in England, to John Piper:

Orders are issued to try Cox by a Court Martial, and a reference has been made by the Secretary at War to the Commander in Chief on the propriety of bringing [Colonel] Paterson forward as a party, and as abetter of Cox – the general opinion is he will be broken or be obliged to retire on half pay as a matter of favor. I have seen the Secretary at War’s letters to the Duke [of York] and to be sure it is a most severe one.50

This letter suggests a deal of intrigue over the case. There may have been someone else in the Corps who coveted the lucrative office of paymaster, and alerted the War Office. Or possibly a staff officer in London noticed both William’s past record and that courts martial in the colony never seemed to convict the panel members’ brother officers (and brothers they may well have doubly been, in the sense of being Freemasons, too).51

At all events, the Duke of York finally did order Lieutenant Colonel Paterson ‘to send Mr Cox, the Paymaster of the Corps, home for “malversation”’.52 The office copy of a letter from the Deputy Secretary at War, Francis Moore, to a Colonel Clinton, who drafted the Duke of York’s letters, makes it clear that William’s prosecution was being demanded at a high level. Moore wrote:

To acquaint you for the information of H R H the C in C that for the sake of example it seems expedient that Mr Cox should be tried by a General Court Martial for malversation in the office of Paymaster; and if such trial cannot conveniently take place in New South Wales Mr Bragge [the Secretary at War] would advise that Mr Cox should be sent home to be tried … [there is] sufficient evidence of his having disobeyed the orders contained in His Majesty’s regulations, by drawing far greater sums than the services of the Corps actually required.

Ironically the Secretary of State, Charles Bragge, MP, later (in 1809) successfully pursued the Duke himself for corruption in having sold army commissions through his mistress in 1806, forcing him to resign, although the Duke managed to get himself reinstated a few years after. To achieve this against the King’s own brother illustrates the change in public morality which was gradually taking place and which William largely ignored throughout his life.

Clinton’s letter shows that disobeying orders was a greater offence than the malversation. It had concluded by saying that any evidence which would counter a plea of necessity on Cox’s part ‘might be useful’: such ‘necessity’ might have been the difficulty any junior officer experienced in supporting a family on his pay. The wording of the letter implies that the trial being held in England was to avoid William being acquitted by his brother officers in Sydney. On the other hand, the incriminating evidence of the regimental agents, Cox (no relation) and Greenwood, was in London. An earlier letter of 7 December 1803 attributed some blame to Paterson for not ‘discontinuing Mr Cox’, but this was not followed up. The overriding impression given is that the War Office could no longer tolerate the venal behaviour of the New South Wales Corps officers. The marker that this set down has passed historically unnoticed because of the great furore created a few years after over the trial of Major Johnston for his part in the Bligh rebellion of 1808.

Although Moore’s letter had been written in January 1804, it was August 1806 before William boarded the Buffalo at Port Jackson ‘under arrest’, leaving his family behind. The new governor, Bligh, recorded William’s recall dispassionately, informing Secretary of State Windham, ‘In consequence of orders which Colonel Paterson received … Mr Cox … [returns] in the Buffalo to answer such charges as will be brought against him’. This was the ship on which Governor King was returning. Due to his illness she did not sail until 10 February 1807 and then suffered great delays. Rounding Cape Horn on 15 March she was struck by lightning and only left Rio, after repairs, on 12 August, reaching Falmouth on 5 November. The voyage had taken nine months.

Major Abbott wrote to Piper on 28 May 1808 remarking that had the ship arrived earlier ‘then there was a chance of Cox being able to state his affairs’. That dim hope collapsed, since William was ‘dismissed the service’ on 9 April 1808, presumably after a trial.53 A detailed search of the fragile courts martial records at the British National Archives has failed to locate the record, although D’Arcy Wentworth’s and other proceedings are there. Normally the date of dismissal would have been the date of the verdict. William was described as ‘Paymaster’, which is how he was listed in the Army List. As mentioned earlier, his subsequent use of the rank of captain annoyed his former fellow officers. Family memoirs claim that William returned because his sister Anne had died. She had indeed, in 1807, but after he had sailed. The statement was part of the veil of respectability determinedly thrown over the less creditable aspects of his career by his descendants.

William had received no pay since his suspension as paymaster in 1803. He had still not received any by December 1808, even though onethird of the pay due had been authorized.54 Government departments were notoriously slow in making payments, from which both King and Macquarie suffered. This explains why he was so long in returning to the colony. He does not seem to have lodged with his brothers-in-law at Red Lion Street, since War Office letters were sent to him at 7 Roberts Row. He did not receive the arrears of pay until the summer and only arrived back in the colony on 17 January 1810, on the Albion, via the Derwent, continuing from there on the Union, as reported by the Sydney Gazette on 21 January 1810. Meanwhile Rebecca was still being promised supplies from the government store in January 1810, when William was back. She was obviously on the margins as far as feeding her family was concerned.55 For all that he returned to family holdings on the Hawkesbury, William must have felt his future was in serious doubt.

Port Jackson as seen in 1817 by James Taylor (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [XVI/ ca. 1817/1])