4 Rehabilitated as Macquarie’s Protégé

There had been an unanticipated silver lining to William’s long absence from New South Wales. He was away throughout the interregnum of the officers’ revolt against Governor Bligh, when he could not have avoided taking sides. Happily, too, Rebecca and her sons had been leading signatories of loyal addresses from the Hawkesbury people thanking Bligh for his help after the 1807 floods. One address, led by James Cox (then 17 years old) attracted 546 signatures at a time when the entire population of free settlers was only 703 (although one must assume that many signatories were in fact emancipated convicts).1 These family actions in support of the legitimate authority, albeit before the officers’ coup d’état, may well have helped William to re-establish himself, just when the privileges of the corps he had belonged to were being overthrown by the new governor, Colonel Lachlan Macquarie.

A tumult of governmental orders followed Macquarie’s arrival. January 1810 was a month few free people in the colony were likely to forget. The Governor immediately asserted his authority. Officers of the New South Wales Corps, now renamed the 102nd Regiment of Foot, were replaced by officers of the 73rd, which Macquarie had brought with him, both in military roles and as magistrates. Thus the detachment at Parramatta changed hands on 7 January. Officials dismissed by the rebels were reinstated, as when the merchant Robert Campbell was appointed a magistrate in Sydney and restored as a member of the Orphan School and Gaol Fund Committee. Lieutenant Colonel Paterson was ordered to close the accounts for his time in charge of the colony (which included his land grant to young Edward Cox). Bligh was to be reinstated as governor for 24 hours and then to hand over formally to Macquarie.2 Annoyingly for the new governor, this well-intentioned move backfired, because Bligh then embarked on a supply ship, the Porpoise, pulled rank as a commodore to take command and, after sailing to Hobart and back, went through a charade of investing Sydney harbour before finally being persuaded to leave. By late February Macquarie was inveighing against the evils of ‘illegal co-habitation’ in a lengthy proclamation – an ineffective argument, because ex-convict women were well aware that marriage would cost them all their rights, including those to property.3

Against this memorably tumultuous background, William wasted little time in rebuilding both his local standing and developing the businesses of private farming and a new one as a government contractor. These were figuratively three corners of the same triangle. To take farming first, he and his sons started to buy farm tools and to acquire stock, although they did not seem to have done this significantly until the following year, perhaps because the rebuilding of his status mattered more, even though Clarendon became the foundation stone of everything he did. Thus on 12 February 1811 he acquired nine of the late Andrew Thompson’s shoemakers’ knives for 9s each, while his son George bought a foal and a young colt for £60. On 14 February William bought 25 sheep and on the 25th he paid £6 for a cask of gunpowder and James bought 20 sail needles for 3s. In March William disposed of 100 sheep and goats for £83 5s.

These activities were among other unrecorded moves which set Clarendon on the way to becoming a self-sustaining community and in which William’s lifelong aide, the ex-sergeant James King, must have participated. Holt recorded that King had been ‘the clerk or steward over the stores’ at Brush Farm ten years before.4 Presumably King had stayed loyal to the family throughout their travails. Although William’s purchases cannot be dated easily, it is clear from his will that he bought even the smallest parcels of land, if they became available, while the development of estates beyond the mountains as part of a family enterprise eventually followed and was an integral part of the way in which he established a family dynasty.

Here a comment from a historian of the nineteenth-century English squirearchy is unexpectedly applicable to New South Wales, fitting the pattern of William’s and his contemporaries’ lives: ‘the landed gentry came in a bewildering variety of size and shapes … but they formed a reasonably homogenous group … they were the untitled aristocracy’.5 The exclusives of the colony included John Macarthur, the son of a hosier in Plymouth, Samuel Marsden, the son of a blacksmith, John Piper, the son of a doctor, Sir John Jamison, William Lawson, an army officer trained as a surveyor, John and his younger brother Gregory Blaxland, middle-class landowners from Kent with considerable social pretensions and, of course, William Cox himself, heir to armorial bearings and little else.

Disparate as these settlers’ origins were, they came to form an identifiable group, to which the ex-convict traders Simeon Lord and Samuel Terry, despite becoming major landowners, could never truly belong. Apart from their being emancipists, this was also due to the interminable quarrels about what constituted a ‘gentleman’. One instance of this was the supposition that since in England a squire was a gentleman and so qualified to be a JP, in the colony the reverse must be true and therefore a JP was by definition a gentleman – except that Lord, despite being appointed to the bench by Macquarie, was not.

This question of gentlemanly status was implicit in William’s rehabilitation. Disgraced or not, he was still ‘an officer and a gentleman’ and it seems that the expansion of Clarendon only got going after William had firmly established this status among the Hawkesbury’s inhabitants. He may well have been short of money, despite selling produce. Advertisements in the Sydney Gazette show him acting as a collector of the debts of the failed business of a Mr Lyons on 17 February and as the intermediary in letting a farm at Richmond Hill on 7 April 1810, as he was over selling a farm at South Creek on 13 October and again in March 1812. On 8 March 1810 he was the foreman of the jury at an inquest.6 On 1 August he was a joint signatory of a convict’s request for a document of emancipation, a move likely to gain him support from local emancipist smallholders.7

Less happily, at this time the trader Robert Campbell had taken advantage of the return of legal authority (with Macquarie) to warn that debts due to Messrs Campbell were to be ‘immediately liquidated’ and, so that settlers on the Hawkesbury and Nepean should have no excuse, he would accept payment in wheat to a representative at the Green Hills.8 William would have been prominent among such debtors, despite having paid a 75 percent dividend. As was seen in Chapter 3, Campbell finally lost his case in 1831. But in 1810 the generalized warning must have reminded William that he needed a stable income. It came in an unexpected way.

The first major step in William’s rehabilitation came on 27 October 1810, following the death of the emancipist magistrate Andrew Thompson, when Macquarie appointed him to the bench on the Hawkesbury with a salary of £50 a year.9 It is extremely unlikely that the Governor would have done this had he considered there to be any stain on William’s character. As explained in an earlier chapter, Macquarie himself had profited from the ‘management’ of regimental funds when he was paymaster in Bombay in 1795. His character and enthusiasms proved crucial to William’s career, although at times inhibiting. As a colonel and later major general he often viewed what were intended to be constructive criticism or proposals as disobeying orders. He kept a near-relentless grip on everything that happened in the colony but ended – as his last portrait reveals – a broken man (a farewell portrait commissioned by William on behalf of the Hawkesbury residents has never been traced).

Macquarie in 1822, ‘the Old Viceroy’ but a broken man (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [ML 36])

Macquarie had come up the hard way. He came from an impoverished minor Scottish clan and in 1777 had obtained an ensigncy in the second battalion of the 84th Regiment, or Royal Highland Emigrants, commanded by a cousin. This taught him the value of patronage, connections and money. Through most of his army career he lacked them and was short of cash. He is said to have remarked that Arthur Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington), who possessed all three advantages, reached the rank of colonel in nine years, whereas it had taken him thirty. His beloved first wife, Jane Jarvis, died in India in 1796. He was married again, to a cousin, Elizabeth Campbell, in 1807, who was to be a considerable force in New South Wales, not least in her classical architectural taste.

Macquarie’s becoming governor was accidental. He was the lieutenant colonel of the 73rd Regiment when its commander, a major general, was chosen to replace Bligh as governor, ending the short tradition of appointing naval post captains. The general turned the appointment down. Macquarie wrote to Lord Castlereagh asking to go instead and, after chancing on Castlereagh walking through London’s Berkeley Square, was given the job. His instructions from the Secretary of State emphasized improving the morals of the colonists, encouraging marriage, providing for education, prohibiting the use of ‘spirituous liquors’ and increasing the agriculture and stock of the colony.10 What the instructions did not cover, but which came to concern Macquarie greatly, was the layout of towns and the erection of handsome public buildings, over the expense of which he frequently dissembled to the Secretary of State. These improvements regularly involved William Cox as a contractor, helping to create William’s fortune. But what was seen in London as their extravagance was part of the reason for Commissioner Bigge being sent to the colony in 1819 to find out what was going on.

When Macquarie appointed William as magistrate, the residents sent an address thanking him for this appointment of ‘a gentleman who for many years has resided amongst us, possessing our esteem and confidence’, effectively a tribute to Rebecca’s leadership in the small community, given her husband’s long absence.11 The Colonial Secretary’s formal letter of appointment indicated that the office carried wide powers locally. William would be ‘Superintendent of the Government labourers and cattle and of the Public Works in the District of the Hawkesbury’.12 He was to report on both of the latter. Reinforced by the prestige and the £50 annual stipend, William now set about further widening his interests, in the community and commercially, whilst gradually increasing the size of his Clarendon estate.

The Sydney Gazette noted William’s social progress in various reports, and his official actions are largely in the Historical Records of Australia. His exertions for the community during a flood in March 1811 were praised. In May he was appointed treasurer of a committee to build a schoolhouse at Richmond, for which he drew up a plan. After Macquarie ordered the setting up of the five towns, described below, in October 1811, the constables were ordered to make a return to William of the farms liable to be flooded – Macquarie was particularly worried about the dangers of floods, which indeed in 1819 took Rebecca Cox’s life.13 Come January 1812 Cox was organizing and signing an address from the residents to Macquarie, congratulating him on his safe return from a voyage. In July he subscribed five guineas towards a new schoolhouse at Richmond (which he might well have hoped to build).

The social peak of this activity was reached when he acted as vice president at a dinner to celebrate the anniversary of Macquarie’s arrival in the colony. The vice president at a military dinner sat at one end of the table and when asked by the president, at the top end, to propose a toast, would rise and do so. On this occasion the tables to seat so many people were set in a semi-circle. The Sydney Gazette’s fulsome description of the dinner, attended by ‘nearly 150 persons, among whom were many Gentlemen of the first respectability’ will bear quoting, as it describes formal colonial hospitality of the time at its peak. There were, of course, no ladies present:

This early watercolour, c. 1809, shows the Green Hills settlement (Windsor) from across the Hawkesbury (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [PXD 388 Vol. 3 no. 7])

The street going down to the river from Thompson Square at Windsor (Author’s photo)

[In] the apprehension that a fệte champệtre would be better adapted to the warmth of the season, a spacious tent was erected in the front garden of Mr Hubert Jenkins, one of the stewards, and fancifully decorated with various ensigns, together with a variety of shrubs and boughs, formed into festoons … on the outside of the tent the British Colours were displayed … At six the company sat down to an excellent dinner, during which the full band of the 73rd Regiment … played a number of appropriate airs.

William Gore, Esq, President, and William Cox, Esq, Vice President, were each supported by a Clergyman on the right … and the rest of the Company placed themselves promiscuously without respect to rank … and the challenge to ‘hob or nob’ was proffered and accepted with a cordiality that was truly gratifying … After dinner succeeded the Toasts, all of which were followed by well adapted airs.

There were a dozen toasts and it was ‘near eleven when the last toast was drunk … the company retiring highly gratified’. It was hoped for the occasion to be repeated.14

William thus honoured not only Macquarie’s anniversary, but implicitly his patronage. However, there were other aspects to the Hawkesbury with which William had to cope as a magistrate and which made it vital for him to be respected. Grace Karskens explains that the popular culture there ‘was seen as notoriously “riotous” and “disorderly” because it was beyond the pale of administration’.15 Andrew Thompson, William’s predecessor, so mourned by Macquarie, had been the constable there as a trusted convict ten years earlier. He had both established some degree of order and become wealthy as a trader, proving that an emancipist did not have to end up impoverished. He would be ‘a hard act to follow’. Finally, the Hawkesbury had been the scene of early clashes over land with the Aborigines, and would be again in 1816, with which William had to deal.

Socially, the Hawkesbury was a tremendous step down from the Parramatta area. By contrast Sir John Jamison, whose father had instigated William’s bankruptcy, but who became a close associate, had his estate of Regentville on the Nepean River near what became Penrith, much more of a gentleman’s location. This underlines Rebecca’s shrewdness in getting her grant for Edward at Mulgoa, a few miles beyond Penrith. Whether William was responding to both local realities and his own by building his house at Clarendon unpretentiously, or whether he was so inclined anyway, is not clear. Possibly it was a bit of both. People’s aspirations, both men and women, are often expressed architecturally, Mrs Macquarie being a good example, as were William’s sons. They built themselves grand houses for the continuance of dynasties. Unlike them, their father seems to have had little ambition over his houses.

Clarendon is described as having been ‘a large irregular bungalow built about 1810’, to which he only added a formal dining room a decade later.16 His grand-daughters, who knew what remained of the house at the end of the century, confirm its rambling character. Although in 1824 William built a much more classically elegant house in Sydney, on the corner of Bent and O’Connell Streets, his correspondence shows that it was intended only for rental to the government. Four years before his death he built another house called Fairfield at Richmond, safe from the floods, where he eventually died. It was later greatly enlarged and is now a hotel, so that it is hard to tell what it originally looked like.

Day to day life on the Hawkesbury involved a continual interaction both with his own convict employees and with ex-convict small settlers, in which undue pretensions would have served William poorly. A most important aspect of his life in the Macquarie years was that he fully endorsed and practised his patron’s belief in the rehabilitation of convicts, once their term was expired or they were given tickets of leave to work on their own account. Macquarie had explained his views to the Secretary of State within four months of his arrival, telling Castlereagh:

I have taken on myself to adopt a new Line of Conduct, Conceiving that Emancipation, when united with Rectitude and long tried good Conduct, should lead a Man back to that Rank in Society, which he had forfeited and do away, in so far as the Case will admit, All Retrospect of former Bad Conduct.17

However, Macquarie named only four men who he had ‘admitted to his table’. They were D’Arcy Wentworth, the Assistant Surgeon, William Redfern, Andrew Thompson, the magistrate, and Simeon Lord, the trader. None had been common criminals, while D’Arcy had never been a convict, and all were men with whom William would have many dealings, both professionally and, in Wentworth’s case, socially.

In fact Macquarie’s statement is curious in two ways. For him to refer to Wentworth in that way was incorrect. D’Arcy was a former volunteer officer and medical practitioner, related to the Earls Fitzwilliam, who had gone into exile to become the colony’s assistant surgeon after three times being acquitted of highway robbery. Although court martialled in 1809 on the grounds that, when in charge of the hospital, where sick convicts had to be fed by their employers for the first 14 days, he had not returned the sick to their employers, he had been acquitted. The Judge Advocate had remarked that he had known D’Arcy for 17 years and he had ‘Conducted himself … with the most propriety’.18 He was described as being ‘a handsome tall man with blue eyes … popular with all classes and both sexes’. He was married to a convict woman and fathered William Charles Wentworth of the 1813 Blue Mountains crossing. The younger Wentworth trained in London as a lawyer and later became a prominent politician, whose path crossed William’s often from the 1820s, as well as acting as his counsel over the action by Campbell.

Macquarie did not mention the Reverend Henry Fulton, the Protestant Irish clergyman who had travelled out as a convict on the Minerva under William’s supervision. Fulton had been conditionally pardoned in November 1800 and fully pardoned in 1805, when a Crown chaplain. He had supported Bligh and been suspended by the rebels, but restored to office by Macquarie in January 1810. He eventually founded a school at Castlereagh, which may have been attended by two sons of William’s second marriage.

Other convicted professional men who came to play a large part in the colony’s development, and with whom William had dealings, included Francis Greenway, who was appointed as the civil architect in 1816 by Macquarie and was subsequently pardoned after building the Female Factory at Parramatta in 1820. He designed various public buildings, the most notable being St Matthew’s church at Windsor, although it has been much altered since, and the court house, still preserved as William built it. What might be called Macquarie’s ‘fit to dine with me’ qualification was odd at the best and very few men qualified for it. Although a great many working-class convicts became emancipated, Macquarie’s readmission to society does not seem to have worked except for a few former professionals. Indeed Macquarie’s position had been officially disagreed with back in 1817, when the Secretary of State wrote that he had been ‘compelled to conclude that most of the emancipists elevated to positions of trust were unfit for such preferment’ and urged restraint on the Governor. 19 Overall the way in which Macquarie viewed criminals had progressed from the classicist ‘crime-is-in-the-blood’ school of the late eighteenth century towards the ideal of rehabilitation, anticipating aspects of the Positivist approach of the 1820s in England. The historian J. M. Bennett considers that ‘In Macquarie’s personality … were mixed a broad sense of justice and a humanity far ahead of Georgian concepts’. Acting as a magistrate William shared this outlook. His recorded judgments show that common sense tempered them, for example when on two occasions he met an unreasonable complaint from a master by simply transferring the ‘offending’ convict to another employer. His sentencing – he was the chairman of three justices sitting together and the others opinions are not known – became tougher after Commissioner Bigge’s visit, although he always maintained that harsh penalties (such as severe floggings) only hardened the criminal.

St Matthew’s church, Windsor, which William helped to build and where he is buried (Author’s photo)

The impressive interior of St Matthew’s church, Windsor (Author’s photo)

The Rectory at Windsor, built by William at Marsden’s direction

A subsidiary part of the magisterial role was that convicts were sent up from Sydney to be allocated to employers by the local JPs, the supervision of government labourers being part of the job. Initially there were too few convicts available for private assignment and on 24 December 1810 the Colonial Secretary, John Campbell, referring to the arrival of the transport Indian, instructed that convicts being sent to the Hawkesbury should be distributed ‘free of favour or affection to the most deserving’.20 A letter dated 7 March 1811 from William to Campbell spoke of problems he had in allocating convicts to employers, particularly ex-convicts who now wanted convicts assigned to them. William wrote:

I have been careful to prevent Prisoner settlers being set down for servants and has [sic] rejected many who have not the means of maintaining themselves, but still the claimants are numerous (170) … there are others still in the list who are very unworthy of Indulgence from the Crown, being bad members of society … also I am of opinion many of the Settlers has [sic] set down more acres in hand than they ever had in cultivation altogether.21

Although initially he allocated himself few men, throughout his magisterial tenure, that is to say for the rest of his life, William considered himself to be one of ‘the most deserving’. He gradually accumulated a substantial number, which reached 128 by 1822 and included many ‘mechanics’ (skilled men). This was later bitterly complained about to Bigge by other settlers, as is detailed in Chapter 8, although he was not alone among JPs in the practice and it was just as true that he always believed in the potential rehabilitation of convicts and helped them towards it.

After Macquarie left, and Commissioner Bigge’s report was acted upon, the ideal of rehabilitation faltered and the aims of punishment reverted to the old view, expressed by the Duke of Portland when he had told Governor Hunter that ‘crimes of a more heinous nature … can only be repressed by a sense of the certainty of punishment that awaits them’.22 This has been explained by the authors of a work on criminology as showing less concern with understanding the nature of the ‘criminal’ and more with developing rational and systematic means of delivering justice.23

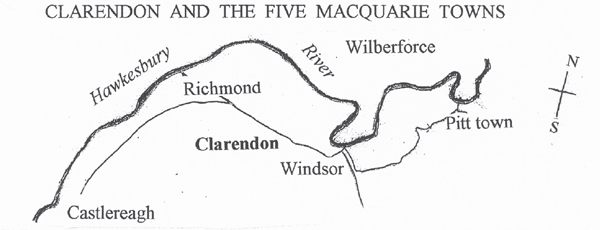

Whilst William’s role as a magistrate rapidly widened his knowledge of the community he lived in and was serving, only Macquarie’s personal writings underline the role which William played in developing the five ‘Macquarie towns’ on the Hawkesbury, the area on which most of his life was centred. These were Richmond, Windsor, Pitt Town, Castlereagh and Wilberforce. The Governor’s ‘Journal of a Tour of Inspection 1810–1811’ describes how he called first at the Coxes’ former farm ‘the Brush’ on 10 November 1810, which Gregory Blaxland had acquired in 1807 and Macquarie found to be a ‘a very snug and good farm and very like an English one in point of comfort’. On 18 November he went out with Mrs Macarthur into the foothills of the Blue Mountains. He next inspected farms granted ‘by the late usurped government’ and on 30 November, a Friday, visited the owners of a chain of farms along the Nepean where ‘we were joined by Mr Wm Cox the magistrate of these districts’ to ‘view the confluence of the Nepean and Grose rivers … from the confluence [where] the Hawkesbury commences’. When they camped that night ‘Mr Cox took his leave of us to go home’.24

They then began a series of surveys to lay out possible towns, with William among Macquarie’s advisers. On 1 December, after ‘visiting the Government House – or more properly speaking the Government Cottage at the Green Hills’, they rode to the Richmond Hill accompanied by Evans the surveyor and William. They found Richmond Hill very steep and covered in brush and wild raspberries, though there was a terrace running parallel with the Hawkesbury River for about three miles. Similarly there was a terrace or ridge at the Green Hills, which was where Windsor would be laid out, overlooking the river. On Sunday 2 December they all went to church, lamenting the loss of the deceased Andrew Thompson’s ‘good sound sense and judicious advice’. Macquarie recorded: ‘Mr Cox and Dr Mileham [also a JP] dined with us today’. On the next day William accompanied them again around the Green Hills farms, Macquarie noting that they ‘yield in this present time very fine crops, but the houses and habitations of the settlers are miserably bad … and liable to be flooded on any inundation … The Revd Cartwright, his wife, Mr Cox and Dr Mileham dined with us.’

William continued accompanying the Governor almost daily, as he identified ‘safe and convenient’ situations for townships, away from potential flooding, sometimes by boat, more often on horseback. Mrs Macquarie also rode on horseback, as well as in a carriage, and met Rebecca and William’s family. By 6 December the Governor had decided upon names for the new towns. Windsor was to be in the Green Hills district ‘from the similarity of this situation to that of the same name in England’. Richmond was named for the same reason, while Castlereagh honoured the Lord Viscount, Pitt Town ‘the late great William Pitt’ and Wilberforce ‘the good and virtuous Wm Wilberforce Esq. MP’. Wilberforce had long taken a keen interest in the affairs of the colony and been responsible for Samuel Marsden going out as chaplain many years before. Macquarie recommended those gentlemen with him to urge the settlers to lose no time in removing their ‘Habitations, Flocks and Herds to these places of safety and security’. The advice had little effect. William himself continued to live on low ground at Clarendon, with fatal results for Rebecca.

Macquarie returned to Sydney for Christmas, but was back in January to mark out the townships. His descriptions show quite vividly how his plans were literally breaking fresh ground. On Thursday 10 January he set out from Windsor ‘attended by family, the Surveyor, the Revd Mr Cartwright, Mr Cox and several other gentlemen’ to view the site of Castlereagh. The future great square in the centre had been marked out and ‘the name of it – Castlereagh – painted on a Board was nailed to a high strong Post and erected in the Centre of the Square’. The same was done in Richmond. On 12 January William went with Macquarie to examine Windsor and Macquarie wrote: ‘The Revd Mr and Mrs Cartwright, Mr Cox, Dr Mileham and Mrs Fitzgerald dined with us this day … and we again drank success and prosperity to the new Townships’. On 13 January ‘Mr Cox and his wife and family dined with us today previous to our return to Sydney’.25 It is fair to say that the Governor’s writings display William as a trusted adviser and official, though not as a personal friend in the way that Sir John Jamison on the Nepean became. Both Macquarie and more particularly his wife Elizabeth, who had an animated social circle around her, appreciated the social boundaries of patronage.

Again the Gazette records some of William’s projects around the Macquarie towns, following the Governor’s tour of inspection, as does the Colonial Secretary’s correspondence. On 26 October 1811 he received payment for fencing the burial ground at Windsor. In 1812 he fulfilled a much larger project in the shape of a new gaol there, plus a house for the gaoler and a wall round it, for which the part payment in October was £350, with a similar payment in October 1813. In that year he also began the Glebe House (parsonage) at Castlereagh, for which he earned a total of £500. This immediately preceded the commission to build the Blue Mountains road.

Meanwhile in July 1813 he had begun to collect subscriptions for a new court house at Windsor. Given that he also supervised the building of local roads, his career as a contractor kept him both busy and remunerated. He never had to face a bankruptcy again. He continued this work throughout his life, despite his growing success as pastoralist. In 1820 he built a new schoolhouse at Castlereagh for the government. One of his most distinguished buildings is the court house, which he completed in 1821. It was designed by Francis Greenway and is the least altered of the architect’s many public buildings. Overall, William was extremely energetic and a good organizer, which was what Macquarie meant when he later called him a man ‘of great arrangement’.

Macquarie’s references to miserable living conditions on the Hawkesbury were nothing new at the time and were to be repeated by other visitors for many years to come. Grose had written, when he settled 22 convicts whose sentences were expiring there in April 1794, that the fertile alluvial soil was ‘particularly rich’, although he did not visit the area himself.26 By 1804 – when William and James were given their joint grants by King – it was becoming the prime agricultural area of the Cumberland Plain, even though in 1800 Governor Hunter had reported that the settlers were ‘more in debt than in any other district’ (a direct result of the officers’ trade monopoly and payment in spirits) and the houses were of a very poor standard, usually only of two rooms with earthen floors. Half the colony’s smallholdings were there.27 Worse, as William would tell Commissioner Bigge in 1820, when these ex-convict settlers were allotted a convict labourer, the pair would often cooperate in petty crime, the unexpressed fear in William’s letter to Campbell of 1811.

A more recent historian of the Hawkesbury, Jan Barkley-Jack, disputes the poverty, arguing that many of the smallholders were successful (William subsequently admitted to Bigge that some were).28 However, John Blaxland told Sir Joseph Banks in October 1807 that ‘a large portion of the farms [were] deserted, the buildings down or tumbling down, the poor creatures almost naked and many of them [with] nothing but maize to eat’.29 Even in 1820 Bigge found the occupiers in a state of abject poverty.30 The disparity between these accounts and Barkley-Jack’s is easily explained. Her account relates basically to the period before 1802, whereas Blaxland and Bigge both visited in the aftermath of disastrous floods which were the cause of Macquarie urging settlers to move to higher ground when he laid out his five towns.

Over the years the Hawkesbury’s fertility gradually became exhausted. When the Coxes moved there in 1804 this was not yet so. True, the soil was relatively fragile and was being overcropped by settlers who had no money for any kind of fertilizer, if they did not own cattle. Nor was it only on the Hawkesbury that this happened. Much of the entire Cumberland Plain was affected, while plagues of caterpillars (army worm) sometimes devastated crops. This was why Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and the young W. C. Wentworth made their iconic expedition across the Blue Mountains to find new land in May 1813, for which they were rewarded, although they did not cross the Dividing Range. A decade before Governor King had sent his Lieutenant, Francis Barrallier, to try to cross but he failed, as did Bass. George Caley, the botanist, penetrated 100 miles from Nattai with a party of four soldiers and five convicts in November 1804, but failed to cross the Great Dividing Range, being stopped by a huge waterfall. This was the most significant of the attempts. There is a cairn of stones supposedly marking ‘Caley’s Repulse’, and so-called by Macquarie, but not erected by Caley.

The first European to find the entire way across the mountains to the plains beyond was the assistant land surveyor, G. W. Evans, who did so in seven weeks from November 1813. Macquarie heaped praise on him in an order of 14 February 1814, reporting that the land he had passed through was ‘beautiful and fertile with a rapid stream running through it [Coxs River]’ at the point where he reached ‘the termination of the tour made by Messrs G. Blaxland, W. C. Wentworth and Lieutenant Lawson.’ The three had, of course, not crossed the top of the mountains, but gone around the side of them towards what is now Hartley. Evans progressed as far as the Macquarie River, 42 miles (68 km) beyond the future site of Bathurst.

Macquarie rewarded Evans with £100 and 1000 acres on the Coal River in Van Diemens’s Land, where he was to be deputy surveyor of lands. He reported the achievement to Earl Bathurst in a letter of 28 April and proposed calling the new country, punningly, West-more-land. He told Bathurst that ‘For the purpose of rendering this new tract beneficial to the Settlers’ he intended to have a cart road constructed across the mountains.31 This would be a very different matter to crossing on foot, as Evans had with his small party. A road would have to tackle precipitous ridges, rising to 3483 feet (1061 metres) at Mount York and higher elsewhere.

Bearing in mind the distances and communications involved, events moved quite fast and it was only a matter of a few months before William met Macquarie in Sydney to discuss the road project. On 14 July 1814 Macquarie sent a letter detailing his requirements. They were exacting ones. The road had to be 12 feet wide to permit two carts to pass each other ‘with ease’, although he preferred it to be 16 feet wide ‘where it can with ease and convenience be done’. In forest and brush ground the timber had to be cleared away to 20 feet. It was to run from the Emu Plains, on the Nepean River, to a ‘centrical part’ of the Bathurst plains, following a track laid down on Evans’ map. Depots were to be established en route.

For this task William was to be provided with 30 artificers and labourers and a guard of eight soldiers ‘you have already yourself selected’. They were to be fully provisioned with food and tools. The reward for the convicts was to be emancipation. Evans had reckoned optimistically that the job could be done in three months with 50 men. When William did it in just under six months with far fewer men he was widely praised. As is clear from Macquarie’s letter, all this had been pre-arranged before his letter was sent. He told Bathurst that William had ‘Very Kindly volunteered his services … he is particularly Well adapted for such a business, being Active and very Intelligent in the Conduct of Such Affairs’.32 By the time Bathurst received the despatch the road was complete and William had already accomplished the dangerous and exhausting commission which made his name.