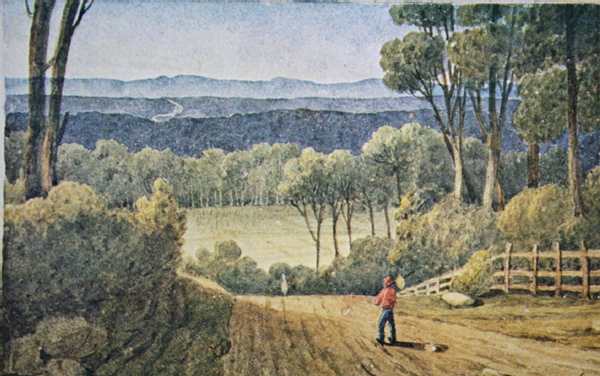

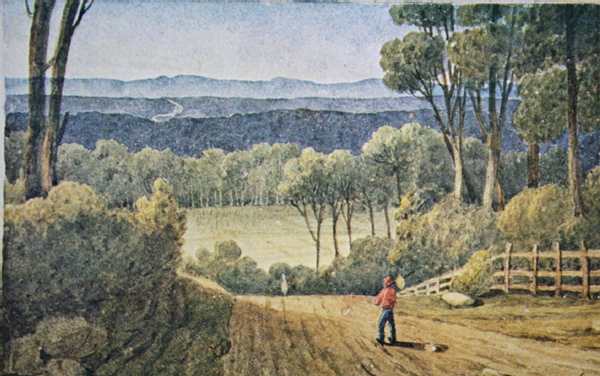

Augustus Earle’s painting of a distant view of the Blue Mountains from Cox’s road in the 1820s (Nan Kivell collection, NLA)

5 The Challenge of the Blue Mountains

William Cox kept a journal of almost all the six months spent building the mountain road. It is a small volume, about seven inches by five, bound in brown leather and was given to the Mitchell Library with other family papers in 1965. Recently an apparently earlier, battered version has been located. Either way in terms of personal papers it is all but unique, since every entry is in William’s own handwriting, expressing his own thoughts, as opposed to his more carefully considered official letters. Although it is unlikely that he wrote it for others to read, it has often been published, including in an online version.1 The entries end before the road was finished, possibly because he kept a record of expenses starting at the back and going forwards, so there were only two pages left blank at the time he stopped. Or, more probably, he felt the road had progressed so far that his presence was no longer needed, that his supervisors could complete the job of reaching ‘the centrical part’ of the Bathurst plains, and he wanted to get on with other contracts. Certainly, on 15 January 1815, the day after the road was finished, he was back at Clarendon, busy submitting estimates to the government for road and bridge building at Windsor.

In fact, had he been less determined and resourceful, William might have failed, since following the ridge along Evans’ route led to Mount York, which the Surveyor and his men only got down with great difficulty and brought the project close to catastrophe at the summit. Not that he could be blamed for that. As the Oxford Companion to Australian History observes, ‘[Gregory] Blaxland was regarded as the originator of the plan of following the ridges as a means of crossing this barrier.’ And as the last chapter notes, Blaxland had not got across the Great Dividing Range beyond.

When William had succeeded in his task, Macquarie expressed, in a generously worded letter drafted by his secretary, John Campbell, ‘astonishment and regret that amongst so large a population no-one appeared within the first 25 years of the establishment of this settlement possessed of sufficient energy of mind fully to explore a passage over these mountains’.2 But this was after the Governor had traversed the route on a tour of inspection in April and May 1815 and he gave no recognition to the efforts of Barrallier in 1802 or Caley in 1804. Indeed when he wrote that the road promised to be ‘of the greatest public utility, by opening a new source of wealth to the industrious and enterprising’, he was also disregarding the reality of other roads, some of which were little better than tracks.

In January 1789 Governor Phillip had led a party of woodcutters to mark out a line of road from Sydney to Parramatta. However, the road towards the mountains did not go that way. The road from Parramatta to the Hawkesbury ran west to Richmond and Windsor, whereas William’s new one would start further south, crossing the Nepean River at a ford near present day Penrith. Today the Great Western Highway largely still follows Cox’s line as far as Mount Victoria and in some sections is not a great deal wider than Macquarie’s specification. It was first realigned in 1823, with a major change passing Mount Blaxland, so that today’s route is much further north than William’s. It has been altered at intervals ever since.3

The Governor had decreed that the expedition would receive ‘provisions, stores, tools, utensils, arms, ammunition, slops [work clothing] and other necessaries’. These would be sent from Sydney to a depot to be established by William on the Emu Plains by ‘two separate conveyances or convoys’ one immediately, the other two weeks later ‘which you will be pleased to receive and take charge of on their arrival there, placing such a guard over them as you may deem expedient, the sergeant commanding the guard of soldiers being instructed to receive all his orders from you for the guidance of himself and party and for their [the stores’] distribution’.

To meet these ideals, the labour gang William assembled was a much less ill-kempt bunch than was usual. A typical road gang depicted around 1815 in the bush near Sydney (the drawing is in the National Library in Canberra) were clothed in ragged trousers, often patched at the knees, wearing an assortment of rough jackets and smocks, and headgear of all kinds from flat caps to battered high hats for protection against the sun. Their guard of soldiers in high plumed shakos, shouldering muskets with bayonets, was dominating them.

William’s men were very much better fitted up and motivated. They had volunteered their services, in Macquarie’s words, ‘on the Condition of receiving emancipation for their extra Labor on the conclusion of it. This is the only remuneration they receive, except their rations’.4 He might have added that they would be provided with clothing, which William replaced as necessary. It has been observed that back in Governor Phillip’s time convicts responded much better to the indulgences and incentives which the military offered than to other employers’ inducements.5 William had been an officer and gave continual minor incentives to the men, whilst at the back of their minds must always have been the eventual reward of freedom. His diary states that the 30 men were issued with a ‘suit of slops and a blanket to each man’. We know that slops included shoes and trousers, because a few were found to have been stolen. The blankets were for the cold of the high ridges awaiting them and later more were issued, as well as ‘strong shoes’ for the rugged terrain.

This was not the only respect in which the gang was different from normal. The word ‘convict’ is nowhere mentioned. William referred to the men by their names and trades as ‘workmen’ or ‘quarrymen’ or ‘carpenters’, while Macquarie had called them ‘artificers and labourers’. Not being labelled convicts must have been mentally invigorating for them. Furthermore, although William had the detachment of eight soldiers with him, the troops were directed towards safeguarding the stores and provisions, not supervising the work.

There were several supervisors, the chief being Richard Lewis, who had that role at Clarendon, assisted by Hobby and Tye, whilst a fourth named Burne was to prove less satisfactory. The following June Macquarie made Lewis a superintendent ‘in the new discovered country to the westward of the Blue Mountains’, under William’s orders, with a salary of ‘£50 per annum and the usual indulgences’.6 William’s 20-year-old son Henry assisted at the depots. The soldiers – on Macquarie’s orders – also prevented curious sightseers from intruding on the project. ‘I have deemed it advisable,’ Macquarie wrote to William, ‘to issue a Government and general order prohibiting such idlers from visiting you, without a pass signed by me.’ He sent copies of this order to be displayed in conspicuous places and directed William to ‘give the necessary order to your guard and to your constable to see it strictly enforced’. This restriction on access was maintained after the road was completed, presumably to prevent convicts escaping up the road, which Macquarie feared might happen.7

When the expedition set out on 18 July 1814 the men shared one defining aim: to finish the job and gain their reward, for which they were prepared to work waist deep in rivers and be wet and cold for weeks on end, apart from the sheer physical effort demanded of them. Seven years later Commissioner Bigge, who had a sniffer dog’s nose for wrongdoing and strong views about not freeing convicts early, attacked abuses of the project, of which alleged abuses William seems to have been unaware. These might have included Macquarie’s subsequently giving the supervisor Lewis the official job at Bathurst. In his all-embracing 1822 report into the state of the colony, Bigge specifically referred to the road. He commented that Governor Macquarie’s policy had been to bestow pardons and indulgences as ‘rewards for any particular labour or enterprise’ and ‘The men who were employed in working upon the Bathurst road … and those who contributed to that operation by the loan of their own carts and horses, obtained pardons, emancipations and tickets of leave.’ He named one convict, Tindall, of having only lent a cart, when Tindall had been a labourer throughout, and asserted that ‘the nature of the services, and the manner in which some of them were recommended, excited much surprise in the colony, as well as great suspicion of the channels through which the recommendations passed.’8 There is no evidence of such reactions in the Colonial Secretary’s correspondence relating to the road.

Happily, the Commissioner did not criticize William personally (though he did on other matters), merely mentioning that those who were employed were selected by Mr Cox and Richard Lewis and that ‘The first principle was capacity for labour and it is stated by some of the free persons, who assisted in it, that the men worked hard and that they were excited to exertion by the hope of receiving emancipations’. This is exactly the impression which William’s journal gives.

Augustus Earle’s painting of a distant view of the Blue Mountains from Cox’s road in the 1820s (Nan Kivell collection, NLA)

William was unworried by the possible problems and had arranged everything a week before Macquarie wrote to him on 14 July 1814. The first entry of his journal is dated 7 July and reads: ‘After holding conversation with His Excellency the Governor at Sydney relative to the expedition, I took leave of him this day’. With the help of Lewis he had already assembled the team of 30 trusted convicts. On 11 July he began ‘converting a cart to a caravan to sleep in, as well as to take my own personal luggage.’ This was completed on the 16th. The next day he left Clarendon at 9 am for Captain Woodruff’s farm, carts and provisions arrived from Sydney and he ‘mustered the people’, not calling them convicts. They were issued with slops. The man in charge of the stores was called Gorman and would feature unhappily in William’s later life at Bathurst.

The next morning they started to make a pass, or ford, across the Nepean. The party found the river banks very steep, as most that they were to encounter were. The Nepean was already notorious for flooding, as William well knew because he had been warmly commended for rescuing a woman caught in the flood of 1806 on the Hawkesbury, previous ones having been recorded in 1795 and 1799. Whatever ‘pass’ he built would need to be flood-resistant. The existing one was merely an improvement on the ford and suffered from flooding. A bridge was only built much later. July 18 and 19 also brought the first of what would become very repetitive observations. The weather was ‘fine, clear and frosty’, some items of slops had been purloined, there were complaints, the first of many, about the food, the pork being deficient. It proved to be underweight. William ‘wrote to His Excellency the Governor for additional bullocks and some small articles of tools’. By the end the Governor’s secretary must have had a small library of such requests, but they were invariably met. In order to speed up re-provisioning, William often obtained supplies from his own estate at Clarendon, while problems with the bullocks used as draught animals to haul supply carts lasted throughout the project.

The next need was for axes, which the blacksmith fashioned from iron and steel provided by William, but ‘the timber being hard, they all turned. Kept the grindstone constantly going.’ These, with hoes, spades, picks, sledgehammers and a small amount of gunpowder, were all the tools they had. On 23 July a hut was fitted up on the left (the further) bank of the Nepean to store provisions and William wrote to the Governor for pit saws, iron and steel, then went ahead to plot the next stage from the Emu Plains, which would cross a creek and ‘begin ascending the mountain’. On 24 July he noted that ‘The workmen exerted themselves during the week, much to my satisfaction’. By way of reward he gave them ‘a lot of cabbage’, which he had exchanged for a pound of tobacco. By 26 July they had made a ‘complete crossing place’ from the end of the Emu Plains to the foot of the mountain, although the ascent was steep and ‘the soil very rough and stony; the timber chiefly ironbark’. The trees were not so named without reason, but the expedition was now well under way, after little more than a week.

There had been various personal disadvantages for William regarding this enterprise. One was being absent from his own farm for a long period. A Cox family memoir suggests that ‘Clarendon still had growing pains’ and asks, in relation to the building of the mountain road, ‘Was the absence from home and family justifiable?’ Macquarie recognized the same point, remarking that ‘Mr Cox voluntarily relinquished the comforts of his own house and the society of his numerous family and exposed himself to much personal fatigue, with only such covering as a bark hut could afford from the inclemency of the weather’.9 As far as organization was concerned, Rebecca had managed Clarendon perfectly well during her husband’s three-year absence from 1806 to 1809, assisted by James King, and William brushed such disincentives aside. He had grown into an extremely determined man and the Governor was correct in admiring his qualities of leadership and personal courage.

Nonetheless, one disincentive was inescapable. Come December, William would reach his fiftieth birthday and would attain that age high up on the mountains in bitter weather. True, he was at the peak of his abilities, but the half century is a moment when any man has to start looking after himself physically. The roughness of the mountains would often mean that the improvised caravan was unable to be manoeuvred up slopes and had to be laboriously taken ahead. Addendums to his diary refer to William sleeping in bark huts, while later diary entries reveal that on several occasions he was ‘completely knocked up’ by his exertions.

The road progressed fast. A resting place subsequently named Springwood was created 12 miles from the ford, beyond the first depot. Secretary Campbell, in his account of the Governor’s tour of inspection in May 1815, described the 12 miles from the Emu ford to the first depot as passing through ‘a very handsome open forest of lofty trees, and much more practicable and easy than was expected’.10 His detailed account of that journey is very helpful in establishing how far exactly William’s party had reached at various times.

Soon the going became tougher and the obstacles more evident. William noted that ‘The ascent is steep; the soil rough and stony; the timber chiefly ironbark’. A superintendent was sent ahead to mark the next five miles through the bush from the depot to the next forest ground. The blacksmith’s forge was brought up and a chimney built for it. The soldiers were moved from the river to the depot.

Confusingly, by comparison with the distances later quoted by Campbell, William recorded, ‘Removed my caravan from the river to the depot on the mountain, a distance of five and three quarter miles and slept there the first night’. The depot was, as William makes clear, not far from the river and was certainly not on the mountain in any real sense. On 28 July he returned home to Clarendon for a brief stay, leaving Richard Lewis in charge, coming back on 1 August when he ‘found the road completed to the said depot, much to my satisfaction’.

In effect they were progressing in a leapfrogging way, as they would throughout the expedition, with William himself at the centre and the advance party ahead, while behind them provisions were moved slowly forward to new locations for the depot. ‘The workmen go with much cheerfulness and do their work well,’ he wrote on 2 August. ‘Gave them a quantity of cabbage as a present.’ Cabbages became a frequent gift to the men and must have been welcome to enliven the carefully counted pieces of pork from the barrels. Green vegetables also ward off scurvy, which did affect one man later.

Despite this good start, 2 August was soured by the fourth supervisor, Burne, refusing to take orders via Richard Lewis, saying he would only obey any from William. The response must have taken Burne aback. ‘I told him I should send any orders I should give to him by whom I pleased,’ William declared roundly. Eventually the supervisor said he would leave. On this William ordered the constable who was accompanying them to receive Burne’s gun and ammunition, he was struck off the stores and the party was informed that ‘he had nothing more to do with me or them’. Permitting such insubordination could have been potentially fatal to driving the project on.

On the following day two working gangs were sent two miles ahead and on 4 August the depot was ‘removed to seven and a half miles forward, as also the corporal and three privates’. The soldiers were there partly for protection against the ‘natives’ some of whom had been heard chattering in the distance after a single gunshot the day before. Nevertheless on 8 August ‘two natives from Richmond joined us; one shot a kangaroo’. It emerged later that William employed them as guides. Later he employed Aborigines, one from Mulgoa and the other from Richmond, at both of which places he owned estates.

The ‘natives’ were very minor nuisances compared to the thick scrub and brush which blocked the road builders’ path for days on end. William complained about it continually: ‘Very thick troublesome brush … Timber both thick and heavy with a very strong brush … brush very thick and heavy from the ninth to the tenth mile’ (8 August). A further hindrance was that good water might be a mile or more from the path of the road. They were briefly visited by G. W. Evans, the deputy surveyor who had established the route but whose track would later prove hazardous to follow. Always ahead of them lay the enticing prospect of ‘good forest ground down in the valley’. The problem was to be getting to it, or rather to a series of forest grounds, from the precipitous slopes of the long ridges which collectively constituted the massif of the mountains.

They ran out of food on 12 August. Gorman reported there were only 14 pieces of meat left and no sugar. At daylight next day William ‘sent Lewis to the depot with a letter to Mrs Cox to send me out immediately 300lb of beef’. Obtaining supplies from Clarendon, rather than from the Commissariat further off in Sydney, would become a relatively frequent occurrence. However, that 13th day of the month, far from being unlucky, although one of the soldiers became ill, saw them out of the brush ground. ‘Gave orders to all hands to remove forward tomorrow morning to the forest ground, about half-a-mile ahead of our work’. On 14 August William: ‘sent Lewis with a letter for the Governor, informing him we were without meat or sugar’. Happily, the next morning ‘at 9.00 a.m. arrived a cart from Clarendon with a side of beef 386lb, 60 cabbages, two bags of corn, etc, for the men’. He does not say what the men felt, but it would have been extraordinary if their loyalty had not been bolstered by these supplies coming from their employer’s own farm. As a young army officer, this author was told, ‘always make sure your men eat before you do’. William knew how important this can be for morale.

They now set off along a 12 mile ridge, as Blaxland had so unfortunately advised. The going through the forest was as bad as through the brush. The trees were gigantic. William noted on 17 August: ‘The timber … very tall and thick. Measured a dead tree which we felled that was 81ft to the first branch and a blood tree 15ft 6in in circumference’. Inevitably there were casualties during the tree felling, typically from long splinters, while both the men’s gear and the tools were wearing out. On 18 August Rebecca Cox came to the rescue again. ‘Got 2lb of shoemakers’ thread from Clarendon and put Headman, one of our men, to repair shoes during the week’’ The blacksmith was employed repairing tools and making nails for the men’s shoes in an improvised forge, for which a primitive chimney had to be built. The evening was stormy, a precursor of bad weather to come, ‘but the wind blew off the rain’. The stonemason went forward to examine a rocky ridge about three miles ahead, the aim being to level it. The roughness of the terrain is unchanged today and adventurous tourists can, and do, become perilously lost in it.

William returned to Clarendon for a week on 19 August, leaving Lewis and Hobby in charge. There must have been a great deal to attend to at home by now, what with up to 100 employees and the lands around Mulgoa as well, where Rebecca had first obtained a grant for Edward in 1804. Around 1811 William had built ‘The Cottage’ there for the boys until such time as they married. When he returned to the road building on 26 August he brought with him his son Henry, who had helped earlier at the depot. He records Henry helping to count what proved to be a satisfactory 75 pieces of pork in a cask at the first depot, but does not mention him again.

There was a minor drama that day: ‘At 10 a.m. arrived at Martin’s, where I found the sergeant of the party, he having died the day before. Sent to Windsor for the sergeant commanding there for a coffin and party to bury him at Castlereagh (the Reverend Henry Fulton’s parish), but Sergeant Ray sent for the corpse to bring it to Windsor. Wrote to the Governor for another sergeant.’ It is all very laconically told, in the unemotional terms with which William would have been instructed to log events as an officer, a world away from the artificially elegant prose of the Governor’s secretary. He finally reached the working party at 2 pm, finding the road finished thus far, although Lewis had left ‘very ill of a sore throat’. This was a precursor of things to come. Continual rain and cold on the mountain would make many of the workmen ill. Meanwhile William recorded of the men tersely: ‘Done well’.

By 28 August William had ‘removed, with all the people, to a little forward of the 16th mile’. Lewis was back and two more natives, Joe from Mulgoa and Coley from Richmond had joined them – promising to remain. But the mountain was proving a formidable obstacle. In the ensuing days they had to remove ‘an immense quantity of rock, both going up the mountain and to the pass leading to the bluff on the west of it’. William decided to make a road off the bluff, instead of winding round it, and had timber cut to ‘frame the road on to the rock to the ridge below it, about 20ft in depth’: not an easy procedure.

When William eventually reached it on 3 September he recorded unemotionally: ‘The road finished to Caley’s heap of stones, 17¾ miles’. This was near present day Linden. It had taken from 7 August to construct nine miles of road. The next day he clambered up to Evans’ cave and got ‘a view of the country from north west round to south west as far as the eye can carry you’. He could even see Windsor. It must have been truly inspiring, because William was not given to praising the scenery. On the Governor’s tour Campbell recorded the country here as becoming ‘altogether mountainous and extremely rugged’. The pile of stones attracted his attention; ‘it is close to the line of road on top of a rugged and abrupt ascent, and is supposed to have been placed by Mr Caley’. The Governor named it Caley’s Repulse.11 As mentioned earlier, the cairn had not been created by Caley at all. Today this is part of an excitingly ‘wild’ Blue Mountains Drive for tourists, but two centuries ago the landscape was menacingly hard to negotiate. Fortunately the one hazard the forests did not conceal was dangerous predators. Australia has none, except crocodiles.

At the same time construction of a bridge had been started further on, over a river between Linden and what is now Wentworth Falls, employing 10 men. There was no water for stock by the bridge, the nearest being in a ‘tremendous’ gulley nearly a mile away. Nor was there a blade of grass. The bullocks helping with traction were soon to be more of a hindrance than a help. On 8 September the wind was high and cold and ‘blew a perfect hurricane’: again a precursor of future conditions, totally different to those they had left on the Cumberland Plain. They would have liked to shoot kangaroos for meat, but saw none, only bagging three pheasants.

On Sunday 11 September – they could not spare the time to observe the Sabbath – William went three miles forward along the road with Hobby and Lewis over two or three small passes to Caley’s pile again. He wrote: ‘From thence, at least two miles further, the mountain is nearly a solid rock. At places high broken rocks; at others very hanging or shelving, which makes it impossible to make a level good road.’ On 12 September the long bridge, the first of many, was completed, except for the handrails and battening the planks. It had taken the labour of 12 men for three weeks, ‘which time they worked very hard and cheerful’. Its dimensions were impressive. ‘The bridge we have completed is 80ft. long, 15ft. wide at one end and 12ft. at the other’. On the approach to the bridge there was a rough stone wall about 100 feet long, while from the top of the mountain to the lower end was about 400 feet. It was, William considered, with evident pride, ‘a strong, solid bridge, and will, I have no doubt, be reckoned a goodlooking one by travellers that pass through the mountain’. He must have been mortified when Campbell’s account made no mention of it. He issued a pair of strong shoes to each man, an indication of the tough going.

William continued to move forward ahead of the road construction, ‘as far as the firemakers had finished’ (burning away the scrub and brush) and keeping ‘a strong party at the grub hoe’. The stone in the rocky ground was too hard to break with sledgehammers and was having to be levered up. There could hardly have been a more basic way of clearing a road. He also observed various birds, like a ‘quite mottled’ cockatoo. The brightly coloured mature cockatoos remain a feature of the forests around Mount Victoria.

On 25 September, a Sunday, while working out ways to conquer a ‘steep mountain’, William noticed a river below running east, the banks of which ‘are so high and steep it is not possible to get down’. This was the river which Macquarie named after him, which empties into the Wollondilly. He now chose the site for his second depot ‘close to a stream of excellent water’ with ‘the grass tree and other coarse food, which the bullocks eat and fill themselves pretty well’. By 2 October the store building, 17 feet by 12, had been weatherboarded, with gable ends. It was to enter local history when it became the Weatherboard Inn, for many years giving its name to the settlement now called Wentworth Falls. This establishes exactly how far the expedition had reached. William reckoned it to be 28 miles from Emu Ford, but unknown to him it was only a little more than a quarter of the way to the ‘centrical point’ of the Bathurst plains. He now returned to Clarendon, handing over control to his supervisors.

William had observed earlier that the country to the north was ‘extremely hilly, with nothing but timber and rocks’. This was the area through which Bell’s Line of Road would eventually run, and spectacular it certainly is. Range upon range of hills, with steep and often sheer escarpments, are bisected by long valleys. Campbell described:

a succession of steep and rugged hills, some of which are so abrupt as to deny a passage altogether, but at this place a considerable extensive plain is arrived at, which constitutes the summit of the Western mountains and from thence a most extensive and beautiful prospect presents itself on all sides to the eye.

It was easy for the secretary to observe all this when travelling in the comfort, if somewhat bumpy, of a carriage. For William, relying on his compass and the muscular brawn of his team, wielding tools that were often damaged and with men falling ill, it was very different. He was trying to avoid using his limited supply of gunpowder if he could. Meanwhile the wind tore at them savagely. ‘The wind has been very high and cold from the west since Sunday last,’ he had written back on 8 September and it had continued, ‘last night it blew a perfect hurricane … but we got scarcely any rain.’ The next several weeks were tiring and frustrating for everyone.

On 3 October they achieved ‘a very handsome long reach [of road], quite straight’, which he called after Hobby. They were still on the top of the mountain. There were many large anthills around. One he measured was 6 feet high and 20 feet around the bottom. In the evening his servant arrived from Clarendon with horses and William left for home the next morning, writing to the Governor ‘stating to him my arrangements’. He would be away until the 23rd, dealing with the sheep and the harvest at both Clarendon and Mulgoa, as well as attending Macquarie at a muster. On that date, close to three weeks after he had returned home to deal with what must have become pressing affairs – especially the ensuing harvest – William was again confronting ‘the mountain’; or rather the next mountain, since he found he was dealing with a series of ridges. During his absence nine more miles of road had been laboriously constructed. He sent Hobby back in his postchaise to the Nepean for a week and also sent back his own saddle horse, which he could not keep ‘for want of grass’.

Richard Lewis returned on this Sunday evening, 23 October, ‘from the end of the mountain, about ten miles forward, having been with three men to examine the mountain that leads to the forest ground. His report is that the descent is near half a mile down … that it is scarcely possible to make a road down; and that we cannot get off the mountain to the north to make a road … much more difficult than he was before aware of’. William responded to this bad news by setting all hands to road-making the next day, ‘being extremely anxious to get forward and ascertain if we can descend the mountain to the south before we get to the end of the ridge’. He wrote to the Governor for a further supply of gunpowder.

A few days later, on 30 October, he recorded seeing to the east northeast ‘a table rock seen by us from the rocks near Coley’s [sic] pile to our right’. This can only have been the Pulpit Rock, which places their position at the end of October at present day Blackheath. From there it would not have been possible to descend the mountain to the south. The Great Western Highway of today veers west north-west after Mount Victoria and goes steeply down the side of the ridge. William sent three men to search for a way down, unsuccessfully. It rained a lot and the ‘blankets belong to the men were very wet and uncomfortable’. On some days they could not work at all. The changeability of the weather was defined by the Governor, when he made his tour of inspection in May 1815, writing that it did not rain, there was very little water in the Macquarie River at Bathurst and the Nepean at Emu Ford was only six inches deep.

William was not in the mood to pen a panegyric about the scenery, but again the Governor’s secretary subsequently did, giving a much clearer description of what William simply saw as a cold, wet and challenging landscape. ‘The majestic grandeur of the situation, Campbell wrote, ‘induced the Governor to give it the appellation of the King’s Table Land … on the south west side the mountain terminates in abrupt precipices of immense depth, at the bottom of which is seen a glen [the forest ground: Macquarie was a Scot], as romantically beautiful as can be imagined, bounded on the further side by mountains of great magnitude … the whole thickly covered with timber.’ This is what Richard Lewis had reported, more prosaically, to William on 23 October. Macquarie later bestowed endless politically deferential names, now mostly forgotten, on various features, such as the Prince Regent’s Glen and the Pitt Amphitheatre (after Prime Minister William Pitt).

On 2 November William decided to survey it himself ‘as a road must be made to get off the mountain’. The next day, having started off at 6 am with Lewis, Tye and a soldier, he found the descent ‘much worse than I expected … The whole front of the mountain is covered with loose rock … the hill is so very steep about half a mile down that it is not possible to make a good road … without going to a very great expense.’ Never prepared to accept defeat, he therefore ‘made up my mind to make such a road as a cart can go down empty or a very light load without a possibility of its being able to return with any sort of load whatever’. In carriage or wagon transport terms this was tantamount to defeat, although ‘such a road would answer to drive stock down to the forest ground’. In his estimation only fat bullocks or sheep would be able to be brought up and the sheep would have to be shorn at the top.

This scene is just as spectacular today. The long forested ridges are bounded by sheer sandstone escarpments, in places eroded into craggy pinnacles and other weird shapes, and with lone trees clinging to their sides, below which lie forested valleys interspersed with grassy plains. Evans had described how on 24 November 1813 he had come ‘to the very end of the Range from which the Prospect is extensive … the descent is rugged and steep’. Having got down it he found a valley that was ‘beautiful and fertile with a rapid stream running through it [Coxs River]’ and then reached the place where the Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson expedition had terminated, west of present day Hartley, and had named a prominent sugarloaf hill as Mount Blaxland.12 The attractions of this forest ground far below were tantalizingly visible to William. When he managed to get down there on foot he found ‘Grass of a good quality … Timber thin and kangaroos – plenty’. But ‘in returning back we had to clamber up the mountain, and it completely knocked me up’. He was now close to his fiftieth birthday.

Despite the fatigue of middle age, William did not give up. He removed all hands further along, to 45½ miles from the Emu ford, and gave them a gill (140 ml) of spirits each to cheer them along. Ever persistent, on 4 November he ‘sent three men to examine all the ridges and gullies to the north, offering a reward if they found a better way down. All returned unsuccessful.’ He decided to get the bullock herds down to the pastures below, since many were suffering from ‘lameness or poverty’ of feed, remarking that they had ‘not carried a single load of anything for me since Sunday week last’. He must have been feeling deeply frustrated, although he did not say so. He was remarkably restrained about his own feelings and health.

The whole group was now forced to camp at the top of the escarpment. Whether William had the caravan with him at this stage is not stated, but the Governor later praised him for having shared his men’s discomforts in a bark hut. There are still two small waterholes near the track to Mount York (named by Macquarie), close to which his men slept in those huts. They are to be found a few metres to the side of the road, quite small, and in soil thick with leaf mould. The overhanging rock ledges where others sheltered are easily identified, too. William described them as ‘so lofty and undermined that the men will be able to sleep dry’.

Some leaders would have accepted this situation as a stalemate and turned back, as earlier expeditions had. Instead, William ordered the blacksmith to make eight pikes for defence against hostile natives, and sent yet another party to find an alternative route down the mountain – which again failed. There were saplings here like white thorn, which grew tall and straight and could be easily bent, and William resolved to send some to Clarendon, an interesting reflection on his lifelong quest for agricultural improvements, even when facing potential disaster. He wrote to Sydney for more gunpowder and spirits and on 7 November ‘went forward with 10 men to commence operations for a road down the mount’. A historian of the mountains, Chris Cunningham, calls the eventual achievement ‘perhaps the most noble of all the stories involved in crossing the Blue Mountains’. But William and his men were not there yet.

The Weatherboard hut at Wentworth Falls was a supply depot during the road building and was painted by John Lewin in 1815. It became the Weatherboard Inn (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [PXE 888 no. 3])

Augustus Earle’s painting of convicts repairing Cox’s road, c. 1826 (Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia)