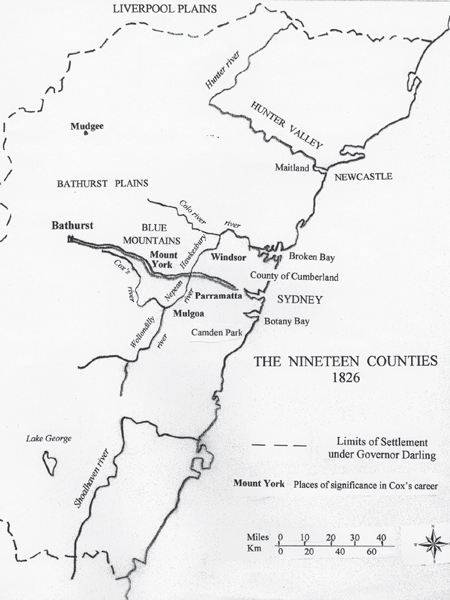

Having been appointed as commandant at Bathurst, William’s life was to be divided for the next three years between the ‘New Discovered Country’ and his home estate of Clarendon. His activities were therefore more sharply split between his increasing official duties and the development of his own estates than they had been before, or would be again. So the present chapter deals with his estates, their management and to some extent with the continuing emergence of the colonial landed gentry. The next will examine his complicated official life, as magistrate and administrator, which had considerable ups and down and exposed him to much criticism, as well as compliments.

The greatest expansion of the Cox estates, like that of most pastoralists, took place on the Bathurst plains. But in 1815 Bathurst itself was a mere handful of simple thatched houses, as depicted by Lewin, the official artist who accompanied Macquarie on his tour of inspection. Although one might have expected the opening up of the area to have been fairly immediate, in fact it was not. There was a long correspondence between Bathurst and Macquarie about this. On 30 January 1817 Bathurst reminded the Governor that ‘You cannot but be aware how much the Length and uncertainty of a voyage to New South Wales must at all times interfere with a very regular communication’.1 There is a note of aggravation in that all too true remark, foreshadowing the official discontent with Macquarie which culminated with Commissioner Bigge being sent out in 1819 to find out what was really going on.

More immediately, as regards land grants, in July 1818 Bathurst ordered that land grants to ‘Civil and Military Officers should be altogether discontinued’, although such officers as were ‘meritorious’ and settling in the colony after retirement could be favoured.2 This crossed with a letter, which Macquarie wrote home in May 1818, about ‘poor’ settlers being permitted to come out, of whom he said: ‘the moment their Indulgences cease, they Contrive in some underhand way to Sell their Farms and take to lawless pursuits, keeping low Public Houses, or becoming itinerant Merchants, Hawkers and Pedlars’. He urged that no more should be allowed out ‘for at least three years to come’.

Instead, only settlers who brought out with them ‘a Clear Capital of at least Five Hundred Pounds … [for] … agricultural pursuits’ should be allowed.3 A few years later Edward Cox asked for land on this basis, supported by his father’s guarantees. More immediately, the historian John Ritchie records that 56 men did so in 1818, that in 1819 applicants numbered 133, and in 1820 the number was 237, most of whom ‘wished to farm sheep’. But those were applicants. In 1819 Bathurst only approved 24, including one woman.4 Even so, this helped to increase ‘demands that New South Wales should be treated less as a gaol and more as a colony’.5 Apparently because of that, Lord Liverpool, leading the home administration, caused the move to be restrained, although the long-distance debate continued to the end of Macquarie’s rule. On 28 November 1821 he wrote to Bathurst proposing a scale of grants from 100 to a maximum of 2000 acres, however great a prospective settler’s capital might be, justifying it by referring to ‘the present Scarcity of Land within One Hundred miles of the Capital’.6 He was obviously not considering land beyond the mountains, for reasons explained below. The expansion westwards, in which William and his sons so vigorously participated, only took place after Macquarie’s departure and increased between 1825 and 1830 for a number of reasons.

The Blue Mountains historian, Chris Cunningham, suggests that this was really due to lack of interest, although he takes no account of Macquarie’s restrictive attitude. Cunningham writes: ‘Despite a further drought in the Sydney region in 1817, there was hardly a rush to take advantage of the western lands. In 1821 there were only 287 people in the Bathurst settlement and most of these were convicts.’7 The colony’s entire population, exclusive only of the military, was only 36,968.8 There may have been a simple lack of demand, although stock was allowed to be pastured temporarily beyond the mountains in 1816 after a drought, but not every potential pastoralist was uninterested. The fortunes of William Cox and William Lawson illustrate this, while expansion formed the background to Cox’s three years as commandant.

In any case, Macquarie’s illogical caution over settlement was a major restraint. Even though few men were needed to shepherd large flocks, the Governor feared that convicts working on the other side of the mountains might escape. From 1816 he had a military guard posted at Springwood on the mountain road. Another reason for his caution was that not all the Cumberland Plain had been taken up. Macquarie apparently discounted the floods, the caterpillars, and that the fertility of the farming land around Parramatta, based upon shale, was becoming exhausted, which had been the reason for Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth’s 1813 expedition. His reluctance to allow expansion is shown by the 2000 acre grant he gave William for building the road still not having been officially laid out when Bigge went to Bathurst in 1819. In his report Bigge wrote ‘Mr Cox occupies a considerable tract of land immediately opposite the station [government buildings] … No grant has been executed upon this land but I understood from Mr Oxley [the surveyor] that it was intended to be conferred on Mr Cox.’9 This was the farm William named Hereford.

During this decade of 1811–20 William’s own holdings on the Cumberland Plain were supplemented in a chequerboard of ad hoc acquisitions. Several appear not have been too scrupulous. For example, James Watson, who had worked on the Blue Mountains road, sold 100 acres to him, subsequently telling Bigge, ‘He gave me £25 for it’.10 Samuel Marsden, the chaplain who was more successful as a pastoralist than as a priest, also collected land piece by piece. The complexity of William’s holdings was eventually shown by his 18 page will, which lists 29 plots of land.11

In fact, this was misleading, since William had worked collectively with his sons in a family enterprise from as early as 1804 and the family’s Mudgee holdings alone came to 100,000 acres. As Brian Fletcher says of Macarthur, Marsden and Cox: ‘They were enterprising settlers who were constantly seeking to improve their possessions’.12 Meanwhile, nothing that William recorded up to 1819 about agriculture mentioned the plight of the unfortunate Aborigines, although he had to deal as a magistrate with a particular outbreak on the Hawkesbury in 1816. Conflict with them had begun on the Cumberland Plain from the time of the First Fleet in 1788.

To return to Clarendon, this was where William, in the words of Barrie Dyster, ‘created the pattern of an ambitious landholder’, as well as on estates at Mulgoa, and west of the mountains. The management of those estates might have had an English inspiration, but was achieved in an ‘indigenous’ manner which evolved in the colony, yet is often not recognized as having been distinctive.13 In reality the colonial model owed little to English landed traditions, even though it was the ideal of the English landed gentry which had motivated the pastoralist settlers from the start. The evidence which William gave to Commissioner Bigge on agriculture in 1820, after he had left Bathurst, provides details of his enterprise which would not otherwise be available.

The acquisition of land in the colony was a totally different endeavour to anything which William, or his contemporaries, could have attempted in England in three respects. First, the estates were created with grants or purchases of uncleared land from the government, which was not comparable with the enclosures of common land in England. Second, miserable as the pay and conditions of farm workers at home were, the colonial estates were built on the foundation of actual forced labour, with all the attendant problems of motivation and competence. Third, many were developed as family enterprises, like William Cox’s, the Lawsons’ and the Macarthurs’.

The family enterprise was possible because the inhibitions of the English primogeniture system were seen to be irrelevant in view of the wide availability of land. Thus the estates of Cox and Lawson were expanded jointly with their sons. William’s comparatively small landholdings at Mulgoa adjoined those of his sons Edward and George, and he had built The Cottage there for them around 1811, although Clarendon remained entirely his. There were also problems in educating children, which seldom occurred in England. William himself had been educated at a first-class grammar school, literally around the corner from his mother’s house. Tutors were easily available for the children of aristocrats at home. But in the colony all such facilities had to be created from scratch, often depending on convict teachers. Finally, there was the role of women in the management of the estates, wives whose lives were a far cry from Jane Austen’s country ladies in that first generation.

There was a further, peculiarly colonial, social dimension to this, directly influencing how estates were run. While Marsden, Bell and others opposed the admission of emancipists to society, William did not. He ran Clarendon personally, as did John Macarthur at Camden Park. But unlike some non-resident landowners, he therefore gained an understanding of convicts’ thinking (which Bigge could not really comprehend, either in terms of how the convicts thought or of why William was interested). His first manager, the Irish exile Joseph Holt, in the early days at Brush Farm, recorded that ‘His good treatment of the convicts in his service had the happiest effect upon many of those who were so lucky as to get into his service’.14 William’s idea of a desirable relationship between master and servant was encapsulated when, in the later interview on convicts, he told Bigge that ‘where the man is capable of performing the task with ease to himself, he pleases his Master who makes his life more comfortable’.15

In agricultural terms, William was among the leading settlers. Bigge had been told by Bathurst that ‘The Agricultural and Commercial interests of the Colony will further require your Active Consideration’.16 He responded to this instruction in his Report on Agriculture, saying: ‘The estates that are in the best state of cultivation, and exhibit the greatest improvement, are those of Mr Oxley, the Surveyor General, Mr Cox, Sir John Jamison, Mr Hannibal Macarthur’. He also listed four others and named William, along with ‘Mr M’Arthur, Mr Wentworth and Sir John’, as owning ‘the herds in which the greatest improvements have been made’.17 These were serious compliments.

The best documented of the estates William owned (after his bankruptcy) were at Clarendon on the Hawkesbury, at Mulgoa on the Nepean, and later at Bathurst, where family cooperation came fully into its own. It is not easy to disentangle his land ownership from that of his sons. A list of his land holdings in 1823 (undated, but probably early January) had him with 5530 acres, out of a total held by the family of 10,690, including 850 at Mulgoa, as shown on a contemporary map.18 After his return from England he had added progressively to the 800 or so acres which the family collectively owned in 1810. There is relative clarity over the subsequent extensive acquisitions across the mountains, described later.

William’s primary estate of Clarendon, close to the river on the Hawkesbury, was a very substantial establishment. He had begun preparing for this self-sustaining community little more than a year after his November 1809 return from England. In 1811 he began buying implements at auction and also trading himself, as described in Chapter 4, in concert with his sons. These were early examples of the family members acing in consort. Well before the time of Bigge’s visit Clarendon had become a self-sustaining community. William told the Commissioner:

We manufacture clothes for Prisoners & frocks from our own wool & boots and shoes from hides tanned upon the estate, we grow our own flax here and make our own harness, we keep a Taylor to make up the cloathing … blacksmiths’ forges and a carpenter also a wheelwright when we can get one.19

In this interview he referred to himself and his sons jointly employing convicts. Quite apart from this possibly being a device to make his own numbers seem less, it shows how his sons’ participation in the enterprise was growing. The second son by William’s second marriage, Alfred, recalled Clarendon when he was a boy in the early 1830s, when it was at its height. In his ‘Reminiscences’ he wrote:

The house … was built of brick and in cottage form, containing many rooms with windows on all sides of it … There were extensive orchards and gardens on one side of the house. Some 50 to 60 outdoor servants were engaged in various industries. There was a flour mill, a cloth factory, a tannery, meat curing house, blacksmith’s forge and buildings in which were to be seen every day at work carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, saddlers, tobacco curers and of necessity butchers and bakers, having quite the appearance of a village.

He remembered a watchman, who had been a convict, and ‘in my mind’s eye I still see nurses young and old, overseers as they were called, and men over whom they were placed in authority. Our head nurse was in her way a somewhat remarkable woman.’20 It is notable that women were placed in charge of male convicts.

The character of the house was of importance, both because it reflected the way William looked at life and because it was the focal point of a community. Rather in the manner of Kenyan and Rhodesian settlers a century later, he added rooms as he needed them.21 Indeed the author Douglas Woodruff has remarked that: ‘Australia … was the Kenya of early Victorian England’, because of that colony’s opportunities in a largely untouched land.22 That comparison is particularly meaningful to this author, who lived in Kenya for many years. William only added an ‘extraordinarily highly finished’ dining room to Clarendon in the 1820s, after his second marriage, presumably to satisfy his new wife’s social aspirations.23

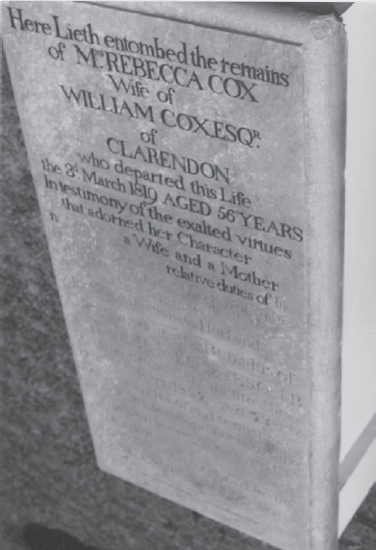

Sadly Clarendon did not have a happy later history. In 1834, having himself been unwell since 1828 and needing medical attention, William moved the family into a more accessible house called Fairfield, away from the river at Richmond. He would have vividly remembered Rebecca’s death in a flood in 1819. He then let the Clarendon house to the auctioneer Laban White.24 It was inherited by George, but does not appear to have been lived in by him or the family ever again.

Fairfield at Richmond, William’s last house and where he died, since extended to be an hotel (Author’s photo)

Organizationally, Clarendon could be compared to other estates. Where it differed was in the unquantifiable human terms of the people who ran it. The estate in that form did not survive many years after William’s death and it must be questionable whether it could have done so without its original begetter, whereas the estates west of the mountains expanded under his sons. William’s great grand-daughters, thought to be the authors of his Memoirs of 1901, knew the house. They described it as:

A large cottage house, built of brick and plaster. It has large handsome rooms, and wooden wainscot runs around the ancient drawing room … But alas in our land woodwork endureth not. We have ‘white ants’, which eat the inside from solid timbers … as you walk across the once solid floor of native timber it gives way beneath the feet, and the gray dust rises that tells of rot, ruin and decay.

All that the Memoirs then say, of around the year 1900, is that ‘the levels are all askew … all is wild and uncared for … the trim paths are overgrown with weeds’.25

George Cox’s letters reveal that he had great difficulties with the estate after inheriting it. He had rented it out and wrote on 2 January 1848, when he was suffering greatly from the financial crash, that he called ‘at Clarendon to see the misery there, and made up my mind at once to lose the half of the rents for that place. The whole farm has not produced 150 bushels of wheat, no hay and not the slightest prospect of corn’. Two days later he set to work arranging ‘a division of the property … these money matters do indeed most dreadfully harass me’.26 He bequeathed what remained of Clarendon to his son Charles, who sold it to a man called Arthur Dight.

Owing to William’s lack of pretensions, Clarendon had never been a house for an aspiring gentleman and his sons had no need of it. William had greatly improved Hobartville at Richmond. In 1824 George had built Winbourne at Mulgoa, where Edward built the classical Fernhill, and Henry built Glenmore, while James created the most elegant and classical of all the sons’ houses, Clarendon in Tasmania.27 The rambling old Clarendon would not have suited their decidedly upper class sense of style. Eventually, Dight’s executors auctioned ‘Clarendon Park, containing 623 acres’ in 1909. It was bought for £7500 by a Captain Phillip Charley. On 12 December 1911 the Daily Telegraph newspaper reported: ‘Part of the old building being a ruin and the rest showed signs of decay, while the century old garden was a wilderness’.28 It finally fell into complete ruin around 1921. A newer house has been built close by, which has been misidentified on a website biography of William as being Clarendon. What are thought to be the remains of William’s detached kitchens still stand, just outside the perimeter fence of the RAAF airfield which now occupies much of the site of the farm.

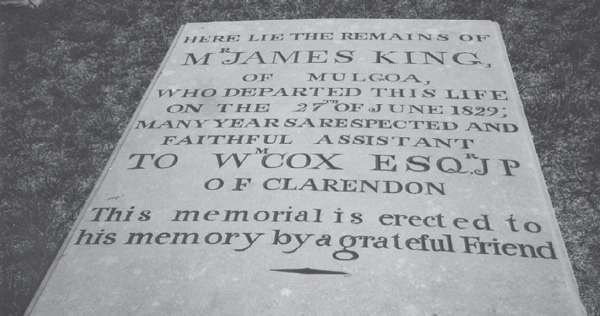

There was a defined structure of oversight at Clarendon, particularly important during William’s absences at Bathurst, although it is clear from the Memoirs that Rebecca was emphatically the mistress of the house. The senior assistant to William on the estate was the former New South Wales Corps sergeant, James King, who was described as his secretary and had been with him since shortly after his arrival. Holt called him ‘the steward or clerk over the stores’ at Brush Farm in October 1800.29 King was both retainer and friend. The Memoirs called him ‘a good man and true’, which he clearly was. He never married, but was godfather to Edward Cox, to whom he left everything. William made sure he had a plot of land at Mulgoa and obtained him local preferment; for instance putting his name forward on 25 June 1812 as slaughterhouse inspector at Windsor.30 He must have played an important role in running Clarendon when William was away. He died at Mulgoa on 27 June 1829 and was buried in a grave close to Rebecca’s in the Windsor churchyard. The tomb’s inscription describes: ‘Mr James King … many years a respected friend and faithful assistant to William Cox, Esq. J.P.’ He was ‘Mr’ whereas William was ‘Esq’.31 His age is not given.

Beneath King came the overseers. The job of an overseer was described by the surveyor Oxley to Bigge: ‘On large estates the supply [of ordinary goods] to convicts’ is usually made by the overseer who is a sort of storekeeper to the proprietor; he sends to Sydney when anything is wanted for the farm & states to his principal what the articles are’.32 The overseer’s account at Camden shows that he was not only supposed to supervise most of the work on the estate, but that he was often sent to Sydney, mainly for the purchase of supplies and to meet new labouring families’.33 The structure at Clarendon would have been little different.

James King’s tomb at Windsor (Author’s photo)

Clarendon’s senior overseer was Richard Lewis, a free man, who had been the senior supervisor during the building of the mountain road and was later sent to Bathurst as the government’s superintendent. He had proper authority there, as when in July 1818 he certified the abstract of the government establishment at Bathurst.34 Oxen given to William as payment for road building were delivered through him.35 As might have been expected, although now a government employee, he continued to look after William’s personal interests, as accounts of the 1822 and 1824 troubles with Aborigines reveal.

At Clarendon there were several other overseers. When he was available, William took a personal hand in matters, as is evidenced by the survival of his farming smock, still in family hands (it may well be that when he told Bigge that they made ‘frocks’ these were in fact traditional smocks). After 1816, his absences made it vital to have a strong support team. Thanks to the distances and time involved in crossing the mountains, he had difficulty reconciling the demands of his various activities. Thus as early as August 1815, soon after the completion of the mountain road, the Colonial Secretary had to order Cartwright and Mileham to alternate as magistrates at Windsor ‘during the temporary absence of Mr Cox, who is on Government service elsewhere’.36 He was actually on another mountain mission with Macquarie and had also been supervising the improvement of the road from Parramatta to the Nepean. In February 1818 he was additionally appointed as magistrate at Bathurst. He was kept more busy than ever he had been.

This official dual capacity ended in August 1819, when Macquarie wrote to William personally informing him that, as Lawson had now been appointed as JP and magistrate at Bathurst, ‘there will be no occasion for your acting in a Magisterial capacity in that country in future’. William was asked to return the commission and warrant to Macquarie. It was signed simply with the initials L. M.37 Macquarie’s phrase ‘in that country’ indicates how distant the Governor felt it to be, as in terms of travel it was. Thereafter William was less frequently at Bathurst and from 1821 left the management of his expanding estates there to George, although sometimes he was physically unable to get away from Clarendon at all. On 15 February 1819 he apologized to Jamison for having to miss one of his many committee meetings in Sydney the next day, because ‘the waters are too much out to attempt it from Clarendon upwards’.38 It was in the following month that Rebecca’s body was recovered by boat.

All this meant that supervision was vital to the Clarendon enterprise. William’s overseers can be presumed to have been instructed to follow his liberal ideas. Certainly Lewis did. William aimed to keep relationships favourable through incentives, culminating with the issuance of tickets of leave, which landed him in such trouble with Bigge. In a personal letter to the Commissioner, previously quoted, William wrote about servants needing small comforts.39 Richard Waterhouse explains: ‘On most properties a task system operated, with servants free to earn extra food, alcohol and money in the time left over once they had completed their prescribed work for the day or week’.40 William believed in task work to provide an incentive and so get the work done effectively. But this was for a private employer. It was less effective when the men were working for the government.

By comparison with Cox, John Macarthur was relatively parsimonious and a great deal less understanding, which points up the favourable aspects of William’s attitudes and the difference between their styles of management, although Macarthur did give some incentives. When asked by Bigge about feeding his domestic servants, he replied: ‘They are fed plentifully … beef, mutton or pork, milk vegetables and fruit and they have Tea and Sugar twice a day’. He did not pay them the £10 a year. ‘I clothe them decently, allow them tobacco and occasionally give them a little money … altogether to the value of £15 or £20 per annum, according to their different degrees of usefulness’.

Rebecca’s tomb at Windsor (Author’s photo)

John Macarthur’s view of the men’s capabilities was also different to William’s. The idea that the convicts would one day be the making of the colony would have seemed inconceivable to him. When Bigge asked if comparisons with England were possible, he answered vehemently: ‘I will not admit of a comparison … those [men] brought up labourers have acquired such habits of idleness, that not one in ten can be induced to feel any pride in the performance of his duty’.41 Quite apart from his notorious arrogance, or perhaps because of it, he lacked William’s understanding of how to motivate men, upon which the management of Clarendon so depended. Atkinson records of the next generation that ‘The gulf between the Macarthurs and their own convicts … was carefully kept up by an array of supervisors and upper servants. James Macarthur explained “We find it more convenient not to give orders to the convicts ourselves”.’ Yet the Camden workers were motivated and there was also ‘nothing of the constant violence between masters and men which happened in some places’.42 But then James Macarthur was a thoughtful and considerate man, one of the few exclusives who developed a coherent vision of the colony’s future, albeit a strongly patrician one.

In one significant way Camden later came to differ from the Cox estates, although after William’s death. When the Molesworth Committee’s report of 1838 recommended the complete ending of assignment, the Macarthurs countered the labour problem by following the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, which had inspired Goderich’s reforms, and began obtaining labouring emigrants from Dorset under a government sponsored scheme. These families became small tenant farmers on the 24,000 acre estate, as did locals. The Coxes did not do this until the 1850s at Burrundulla (near Mudgee), when George Cox ‘set up a system of tenant farmers, but continued to work most of it himself’. He also sold some of the farms to tenants, presumably to alleviate problems.43

The great importance of assigned labour in developing and running estates in the earlier years is emphasized by the sheer size of William Cox’s labour force. In 1822 he maintained an unusually large number of assigned convicts, as well as six who were free by servitude and had chosen to remain with him. In addition to agricultural workers, he employed carders, weavers, stable boys, a carter, a horse shoesmith, a gamekeeper and watermen, as Alfred recounted. It is small wonder that these aroused envy from other landowners. Unusually, he also employed a wheelwright, named Kendall, who had been assigned to him on 25 October 1814 but who moved on.44 In 1820 one of the free men was Richard Kippas, reputedly the ‘best fencer and hurdlemaker at the Bathurst settlement, since pardoned’. He appeared on the 1820 Hawkesbury ‘Return of Tradesmen’ as a wheelwright working for William of his own will.45 This was the very same Richard Kippas who made complaints to Bigge against William, as will be seen in a later chapter. In his evidence given to Bigge on 29 November 1820, presumably at Windsor, Kippas explained that he had broken his leg and been in hospital at Windsor, after which ‘I came out and went to Mr Cox … and am still with him’.46 William must have been a good person to work for, since any man with Kippas’ skills was in demand.

There does, however, appear to have been a deliberate attempt by William to confuse the Colonial Secretary as to the numbers he employed, even allowing for family collaboration. In 1820 he had told Bigge that he and his sons employed about 100 men and ‘we manufacture clothes for Prisoners & Frocks from our own wool & boots and shoes from hides tanned upon the estate … we keep a Taylor to make up the clothing’.47 On 30 March 1823 he wrote to Secretary Goulburn saying that ‘on an average of the last five years I have employed jointly with my sons George and Henry Cox of Mulgoa from seventy to one hundred convicts free of Expence to the Crown’. He listed them. Then on 30 April 1823 Edward wrote from Fernhill at Mulgoa, transmitting a list of ‘one hundred now in the employ of my Father, self and Brother Henry’ and speaking of ‘exertions both for my own good and the benefit of the colony’.

The figures they had submitted had evidently been queried by the Colonial Secretary, because William wrote to his son George on 17 May of that year, asking if he was agreeable to providing a separate list ‘of convicts maintained by us during the period of six years’. The aim was ‘to shew that we have maintained a considerable number of them more than the Land Regulations require during the last six years as this appears to be what Major Goulburn requires’.48 Some complicated ‘back of the envelope’ mathematical calculations followed and the family papers in the Mitchell Library show how he arrived at these ‘averages’. There is no record of whether Goulburn was satisfied, but the history of the family collusion suggests that he had been justified in asking.

The overall convict employment by William in 1823 was officially listed as 113.49 But the figure conflicts with the 1822 Muster, where a careful analysis of the names shows he had 128 assigned convicts. These included a waterman (Clarendon was by the river), shoemakers, shepherds, weavers and a woollen manufacturer.50 The number had increased rapidly after his second marriage in February 1821, before which they totalled 104.51 Subsequently William also benefited from a scheme introduced by Governor Brisbane (and abandoned by Darling), under which government convicts were hired in groups to clear and prepare land for settlers. At the November 1822 Muster he had 15 of these.52 The accusations made against William over using his position as a magistrate to obtain the best convicts appear never to have stopped him doing so.

Governor Macquarie was concerned for the wellbeing of female convicts. A circular sent by Campbell to magistrates on 24 August 1811 told them that ‘a vessel being daily expected with female convicts … His Excellency proposes indenting these females … among settlers … as may require their assistance in the necessary business of a country life’.53 But William did not share the Governor’s view on females being paid. He wrote to Bigge in May 1820, saying that although they were entitled to a wage of £7 a year, he thought they should not be paid at all. ‘Their situation is totally different, they do not draw a ration, but live as the family do … get regular meals, have their tea or milk and are not in want of anything. They should be found in decent and proper apparel, but not any wages allowed them.’54

The reason for this view, or prejudice, is not entirely clear, beyond that the women were living with the family and were therefore outside the system of incentives which William gave to the male convicts for defined jobs. In England living-in female staff were paid, as well as receiving board and lodging. As long before as 1658 a cook in Hertfordshire had received £2 10s a year and a chambermaid £3.55 In 1810 at the Duke of Rutland’s Belvoir Castle, admittedly a wealthy aristocrat’s establishment, housemaids were paid eight to nine guineas (£8 8s to £9 9s), while ‘Her Grace’s woman’ earned £20.56 Kay Daniels, making a comparison with male convicts, points out: ‘Domestic work was not like task work, measurable and discrete … it flowed into the whole day’.57 In terms of having female convict servants for herself and the house, Rebecca was undemanding, most of the time having only two, as in 1818.58 Bureaucracy being what it always will be, she was assigned another, Jane Williams, on 27 January 1820, ten months after she had been drowned.59 Anna had three assigned women, as well as, from her son Alfred’s account, the free women who were running the household and would have been paid.

The women on Hawkesbury farms were few. In 1800 less than half the Hawkesbury farms had a woman living on them.60 Where free settlers were married, the wives were of huge importance in the organization of an estate, especially one relatively so distant from Sydney (Clarendon was three days by river, a day along the ‘roads’). The historian John Gascoigne writes that: ‘Women agricultural improvers such as Elizabeth Macarthur were valued for the results they achieved rather than criticized for stepping out of their traditional domain. And women were associated with the civilizing virtues … gender roles could work in favour of women.’61 But the conversation of lady-like women, and their ideas, were wholly overshadowed by those of their men and Elizabeth Macarthur must have been virtually alone in making her voice respected when she arrived in 1790.62

Rebecca’s unsung farming efforts can be directly compared to the better known and much longer lasting ones of Elizabeth, during John Macarthur’s absences between 1801 and 1817, when she was also bringing up young children. It can be assumed that the two women knew each other. It also possible that the reason Rebecca does not seem to have been invited to Mrs King’s social occasions for ladies in her new drawing room of 1804 might have been William’s disgrace, as well as the distance involved, even though Governor King assisted William materially himself.

Although both wives were propelled by their husbands’ circumstances into decision making roles, in Rebecca’s case her actions went almost entirely unrecorded. She is described in some family papers as having been ‘An early day society woman, whose name was always mentioned at social events. She took part in every good work.’63 However, this account was written a hundred years later and there is nothing to indicate that she was a society woman. Present day descendants emphasize that she was remembered as a very caring person. Holt thought in 1803 that ‘She was a complete gentlewoman’, despite her hardships.64 She had signed the Hawkesbury residents’ 1807 address of welcome to Bligh and in 1808 was a leading signatory of two petitions thanking the Governor for his help after floods.65 Atkinson suggests that it was unlikely that many ‘of the 244 signatories to the Hawkesbury address understood the fine line between acquiescence and obedience’.66 Whether that is correct or not, Rebecca displayed leadership in the community.

According to Atkinson, ‘Women were conspicuous consumers’.67 But it can only have been many years after the 1803 bankruptcy that Rebecca might have become one, if ever (unlike Anna). Back in 1803 and 1804 she had been faced with replacing basic household equipment and her principal supply was of fortitude. During William’s absence, when he was receiving no pay due to being suspended from office, she had to feed her family. With total family landholdings of about 800 acres, and convict labourers, she would have grown much of what they needed themselves, plus a surplus for sale. But they could not produce everything and basic prices were high, sometimes exorbitant. ‘Sugar two and six a pound,’ Mrs King, the wife of the Governor, wrote, ‘butter four shillings, soap six and tea £4. “The common necessaries of life are far, very far, beyond my reach”.’68

These prices might be why Mrs King generously lent £300 to William, even though she and the Governor were in straitened circumstances themselves. Wheat had rarely cost more than 10 shillings a bushel, but by August 1806 it was fetching two guineas a bushel and maize £2. Three months later both maize and wheat were selling for £4, thanks to speculators driving up prices.69 Not that meals were often grandiose, even for the well- off. At Sir John Jamison’s, ‘they seem to have been fairly simple, rhubarb or pumpkin pie and wholemeal bread baked in dripping were considered luxuries and appeared on Sundays. Fruit certainly was plentiful.’70

One of the most challenging aspects of describing William’s domestic life is that there is so little known about Rebecca’s contribution at Clarendon (slightly more has survived about Anna). With that notable exception of Elizabeth Macarthur and also the remarkable convict midwife on the Hawkesbury, Margaret Catchpole, the domestic lives of women in dairying, provisioning, cooking, washing, dances, courtship and children are completely absent from contemporary accounts. Despite the efforts of recent female historians to reconstruct their roles, there simply are very few contemporary records. The women’s activities seem not have been considered central to the lives of men, particularly pastoralists.71 There is a great contrast here with the wives of the next generation of Coxes, who entertained and wrote letters to friends, some of which correspondence is given in Chapter 13.

That Rebecca was both instinctively practical and generous is shown by her taking the present of wine and rum to the Holts after William had crossed swords with Joseph Holt in 1800. Only one letter written by her is known to this author and sadly it is a transcript, so nothing can be deduced about her character from the handwriting.72 But the wording is still revealing. She wrote to Macquarie from ‘Clarendon Farm, Hawkesbury’ in January 1810, very soon after William’s return from England, pleading for confirmation of a land grant ‘given to my youngest son [Edward, then aged four] by Colonel Paterson’. This grant had been given during the Bligh interregnum. She enclosed the deeds, trusting that she might be ‘deemed worthy of a renewal of the said Grant for my little boy & more particularly for the present use of my stock, which is much in want of fresh pasture, the food on the common they now run being greatly exhausted’.73 This letter makes it clear that Rebecca actively ran Clarendon while William was awaiting trial in England and that she was reduced to grazing her cattle on common land. More significantly, it shows her displaying remarkable foresight in extending the family estate into a new and promising area.

This grant for Edward was at Mulgoa, on the Nepean River, a good 28 miles (45 km) south-west of Windsor as the crow flies, and further by cart track. It extended the family enterprise into what amounted to a fresh start. Years later, when Edward had completed five years training in sheep farming in Yorkshire, both he and William continued enlarging this landholding.74 In the end Mulgoa became like a family estate, although the Blaxlands also had land there. William built a dairy and cheese factory, which eventually became the school, and in 1881 George Henry Cox donated land for a new one. Edward donated five acres for St Thomas church, where many generations of Coxes are buried, and established a racehorse stud, with 44 brood mares.75

In 1810 Rebecca must still have been very conscious of her husband’s disgrace and unlikely to have been in any Sydney social circle. Nor, when he was restored to favour by Macquarie, does she seem to have been in Mrs Macquarie’s very active one. Later on, although William accompanied Macquarie on his surveying tours of what would become the five towns in 1816 and dined with him, the Governor did not stay with the Coxes, but camped or stayed in a government cottage.76 When he embarked on his tour to Bathurst in 1821 he stayed at Jamison’s Regentville.77

Possibly during Rebecca’s time Windsor was simply too far out to make socializing easy, although that did nothing to stop Anna. Where Rebecca does match an overall analysis of settler motivations is that, like Elizabeth Macarthur, she clearly thought of her children as ‘future inhabitants of their native country’. When the Macarthur family first came to the colony it had not been ‘as a promotional step to somewhere else’.78 Nor did the Coxes see it that way. This predicated a considerable preoccupation with the children’s education, which was also to concern William after his second marriage.

The education of the landed gentry’s children was crucial, not only to those children’s own futures, but to the future management of the family estate, which William and Rebecca had begun to build up from 1804 onwards. When the couple sailed from England in 1799 they had left their two eldest sons, William and James, at the grammar school in Salisbury, spending their holidays with friends in Somerset.79 William must therefore have hoped that their education would parallel his own at the Queen Elizabeth I Grammar School in Wimborne; and indeed it was to a standard which enabled William Jnr to be commissioned into the New South Wales Corps in 1808. The two eldest boys were only brought out to the colony in 1804, when they were respectively 15 and 14 years old, as was explained in William’s letter of 28 July 1804 to John Piper, quoted in Chapter 3. In that letter he said he had ‘got 250 acres of ground for them with four men … as other settlers have’.80 So their careers as landowners had begun. But for the younger children education was less easy.

A school was run by the Reverend Richard Cartwright, the chaplain on the Hawkesbury. He testified that parents were ‘eager to have their children educated … They came to school for unpredictable periods between about four and twelve years old.’ This has the sound of emancipist small farmers’ offspring, although Bigge found those children ‘manageable when treated with kindness’.81 In any case, by 1811 only Rebecca’s last two children, Maria and Edward, were as young as that. Probably Rebecca taught them herself when they were very young.

For the boys of William’s second marriage the solution may have lain in a school established later at Castlereagh by the Reverend Henry Fulton, who had travelled out on the Minerva with them in January 1800. In June 1814, after involvement in the rebellion against Bligh, who Fulton supported, he became resident chaplain in charge of Castlereagh and Richmond. He is thought to have been helped to this by William and rapidly established a seminary for ‘young gentlemen’ at his parsonage.82 W. C. Wentworth described it as it was around 1818. There were: ‘Several good private seminaries for the board and education of opulent parents. The best is in the district of Castlereagh and is kept by the clergyman of that district, the Rev. Henry Fulton, a gentleman peculiarly qualified both from his character and acquirements for conducting so important and responsible an undertaking. The boys in this seminary receive a regular classical education.’83 Time there would have been followed by terms at the King’s School at Parramatta, which Alfred says he attended.

William subsequently built a new Castlereagh schoolhouse for the government. In April 1820, after Rebecca’s death, he reported its completion to Macquarie in something of a self-congratulatory tone: ‘This new building in the Township is made strong, neat and useful, but expensive … Knowing it was Your Excellency’s wish to have this useful building completed without delay I feel much pleasure in thus reporting it’. It would also be used for Divine Service. ‘The person Your Excellency sent us as a clerk & schoolmaster will, according to Mr Fulton’s opinion, be properly able to perform his duties.’84 It sounds as though Fulton handed over some of his teaching to the clerk. Nonetheless, William had problems educating his second family, although dynastically they would prove to have little importance, since only one of the men remained in New South Wales.85

Asking for assignment favours, as ever, William wrote to McLeay on 14 September 1826 from Clarendon:

In the Gazette I have received have observed an English ship is arrived with prisoners, will you have the goodness to cause an application to be made [to His Excellency] for a man fit to teach two of my young children aged three and five years their reading and writing, they are too young to send to a boarding school and we have not a day school near us.

This assignment was ordered on 22 September.86 Apparently it did not last, because early in 1827 a young immigrant called Alexander Harris, who had been arrested for travelling with no visible means of support, was offered work. Cox intervened, saying, ‘I have two children who need a tutor. Would you like the job?’This seems to have been the same Alexander Harris who, 20 years later, in 1847, published Settlers and Convicts; or recollections of Sixteen Years Labour in the Australian Backwoods. He had arrived in 1825 and, although an educated young man, was living as a vagrant. William must have seen something worthwhile in Harris, a capacity in keeping with his liberal views. 87

Alfred makes no mention of Harris, only saying that when he was older: ‘The first school that my brother Tom and I were sent to was some 10 or 12 miles from home kept by the Rev. W Wilkinson. He had the reputation of being a fair classical scholar … but when in a passion used to knock about in fine style.’ In terms of location this might have been Fulton’s school, which was famous. Of Wilkinson’s establishment Alfred said, ‘we were somewhat proud of him and ready enough to proclaim to the world that he had been our schoolmaster’. He also recorded: ‘My brothers and myself were packed off to a public school at a somewhat early age. We had of course no opportunity of riding there, but when our holidays came round, were again quickly in the saddle, to the pride of our father, and somewhat to the concern of our mother.’88 The two boys were next sent to the King’s School at Parramatta, where there was ‘a pretty strong contingent of boys not attending the King’s School … ever ready to try conclusions with us … we had in our little way “Town and Gown” encounters’. The charges for Board and Tuition were £28 a year. Their minds were ‘saturated with Greek’ by one of several masters.89 Alfred made no mention of how his sisters were educated.

Overall, in the management of his estates William appears to have been in pursuit of farming improvements from the start. Even though he had been a clockmaker in Devizes he must have been alert to farming techniques, or was encouraged to be by Holt. He began breeding merino sheep at Brush Farm in the early 1800s. Originally land was cultivated by hoeing around the stumps of trees, in spite of the gain there would have been from grubbing out the stumps. This was because convicts would not perform well enough grubbing stumps to even pay for their rations. Holt recorded that the men were using hoes at Brush Farm in 1800. William is said to have estimated that 15 men with the plough equalled the work of 300 convicts with hoes. The removal of stumps from the ploughlands gradually became more general.90

When Commissioner Bigge commended Cox’s farming it was not without reason. Improvements were his lifelong concern and even if he might have been unaware of the Enlightenment as an intellectual movement in Europe, what he carried through in practice was certainly enlightened in the best sense. His initiatives took two forms; improving the cropping locally on the Hawkesbury and experimenting with ‘artificial grasses’ to provide better fodder for grazing animals.

Bigge asked him in 1819 how some farms retained their fertility. He answered: ‘A farmer can by raising artificial food such as rape, clover, turnips and English grapes, maintain a flock of sheep and the manure from them will enable him to raise his crops of wheat’.91 Clover, lucerne and sainfoin were far more nutritious than the indigenous grass for animal fodder. W. C. Wentworth claimed in his description of the colony that: ‘The natural grasses are sufficiently good and nutritious at all seasons of the year, for the support of every description of stock, where there is an adequate tract of country for them to range over’. But it seems unlikely that he was right, given the efforts that were made to grow better fodder.92

Bigge reported on this subject that: ‘These gentleman [Oxley, Cox, Jamison, Hannibal Macarthur, Redfern, John Macarthur, Throsby and Howe] have turned their attention to the culture of the various qualities of artificial grasses; and from the experiments they have already made, there is every reason to expect that the supply of food for sheep and cattle may be greatly augmented’. The improvements took two forms: introducing better farming techniques and the improved breeding of sheep. This reflected the values of an English landed class, which had become convinced of the possibilities of increasing wealth by the application of improving techniques.93 In line with this belief William became a founder vice chairman of the Agricultural Society in 1822.94

At the same time, managing a large estate involved near-continual interaction with the Aborigines, although not necessarily in conflict with them. William employed Aborigines satisfactorily at Mulgoa in 1826. But Mulgoa was also a potential flashpoint. Settler relationships with the two linguistic tribes whose boundary met there, the Dharug and the Gundungurra, had been extremely volatile. Both to them and the settlers the river was of great importance.95 In 1816 the Sydney Gazette had reported an attack at Mulgoa in which a shepherd and 250 sheep were brutally killed, the sheep having their eyes gouged out.96 This had been during a severe drought, when river water was crucial. By the 1840s the ‘Mulgowie’, as their remnants became known, no longer led a traditional life. The whole issue of relationships with the Aborigines is dealt with in Chapter 11.

Although that issue is now far more important historically than it was seen to be by either government or settlers at the time, it should not detract from coming to conclusions about William’s management of Clarendon in the larger context of the colony and the emergence of its local landed gentry. The early colonial estates, whether pastoral or agricultural, Clarendon being a combination of the two, evolved to suit physical and social circumstances which were barely imaginable in England. This was both in the environment and in the employment of forced convict labour, even though the living conditions and wages of English farm labourers, as William Cobbett pointed out in the 1820s, made them little better off than slaves. The success of those management methods enabled the exclusives to turn themselves into a dominant class.

William’s estates were never the largest in the colony, but they were among the most efficiently and humanely run. Ambition was at the core of the early settlers’ lives and William did indeed create the pattern of an ambitious landholder. At the same time, his understanding of convicts’ thinking and motivations, his basically liberal outlook and his willingness to mix with emancipists added unusual dimensions to the way he worked. This is not to suggest that his attitudes and actions were unique, but they were untypical of his class and not shared by quite a few of the Pure Merinos. It remains greatly regrettable that so little detail is known about Rebecca’s central role in establishing what became more and more of a family enterprise after her death in 1819.