The Female Factory at Parramatta – magistrates sent recalcitrant women convicts there (National Library of Australia, ref NK/12 47)

A gentleman much distinguished for experience and sagacity [and having] many of the qualities that are essential in a magistrate, who is to administer the law in New South Wales.1

John Thomas Bigge in his 1822 Report on the Colony

The life of a magistrate in the colony in the early years was more turbulent than might have been imagined, dealing with many more social problems than simply administering justice. As explained in Chapter 4, William was appointed in October 1810 to be ‘Superintendent of the Government labourers and cattle and of the Public Works in the District of the Hawkesbury’. The implications of this were far-reaching, including allocating convicts to masters and dealing with the ensuing problems. He continued in office until his death in 1837, a period little short of 27 of the 37 years he spent in the colony, making his career on the bench a significant part of his life. Additionally, during the period from 1815 to 1819, in spite of his home remaining at Clarendon, he both administered the Bathurst area, where he carried out various exploratory missions for Macquarie, and acted as a magistrate there as well as on the Hawkesbury.

At Bathurst he was responsible for fitting out and supporting the surveyor Oxley’s expeditions, to which Macquarie attached great importance. He also conducted expeditions himself, which ‘added to the knowledge of the country through the exploration of much of the Lachlan River region’.2 All this was a considerable burden for a man now in his fifties who had admitted to being ‘knocked up’ when building the mountain road. Worse, if it brought him credit, it also brought vituperative attacks on his probity. One of his responses has been quoted in the Foreword, when he told Bigge on 4 December 1820, after he had handed over the Bathurst appointment:

There is not a magistrate in the Colony who has given as much of his time to the business of the Crown & the public these ten years past as myself … If any man ever laboured amidst a den of thieves and a nest of hornets it is myself.3

Although criticizing William for giving too many tickets of leave to convicts, Bigge respected him as a magistrate. Accordingly, this chapter looks at the various sides of his public life in the decade ending in 1820, not forgetting that energetic and constructive men invariably attract criticism.

In spite of displaying humanity and good sense, William became the target of complaints from his fellow settlers for favouring himself in the allocation of skilled convicts. He also incurred a considerable number of complaints by convicts themselves, originating from his time at Bathurst. These never resulted in action being taken against him. Nonetheless, Bigge was highly critical of the way he had employed convicts on the other side of the mountains, which the Commissioner claimed, ‘excited much surprise in the colony’. As mentioned earlier, there is little evidence that it did.4 Bigge’s investigation into the state of the colony was the most exhaustive survey of all aspects of life in New South Wales carried out up to that time and he made that survey immediately after William’s term of office at Bathurst ended. He also took an unusually large amount of evidence from William, most of which is examined in Chapter 9.

Administration of the law was a central feature of William’s activity, both at Bathurst and on the Hawkesbury. Bigge particularly asked him about punishment.5 His replies, and the details of cases he heard, shed light on much more than William’s own attitudes. They illustrate the daily aspects of life in what was, after all, a penal colony. In England corporal punishment was a harsh fact of daily life for many children, criminals and men in the military forces. Despite the horrors of the lash, Bigge appears not to have thought its use controversial. William’s own earlier reluctance to order flogging had slowly moderated. As a magistrate he was not empowered to deal with the worst crimes, but those he and his fellows on the Windsor bench did deal increasingly strongly with such as fell within their jurisdiction. The later sentencing possibly reflected a more severe regime of punishment in the colony, following Bigge’s visit, which had an impact long before his reports were presented to parliament in 1822 and 1823.

Three sentences given at Windsor between 1811 and 1825 contrast with the six lashes William ordered for the mutineers on the Minerva in 1799, although it is impossible to know how far, as senior magistrate, William prevailed over differing opinions on the bench. At the commonsense end of the scale he twice sent a man to another master, with no punishment, after unreasonable complaints by the original intemperate employer.6 Other of his sentences were proportionate to the offence and vividly illustrative of daily life on the Hawkesbury.

Thus on 10 June 1820 William and John Brabyn heard a case brought by William Bowman (the employer) against James Turner ‘Convict servant’, revealing behaviour by Bowman which was unnecessarily harsh. It is probable that this master employed very few convicts. Turner was accused of ‘neglecting his work and that he does the same in an improper manner and also for being insolent when reprimanded. That Complainant pushed him [i.e., Turner] out of the garden and directed him to Windsor, which he refused and abused Complainant greatly.’ Turner responded by saying that he had lived with his master five years and a half, ‘in the whole of which time his Master has never expressed any dissatisfaction of his conduct’. The circumstances were that he had been told to wheel some dung in a barrow, but the ground being soft he took the dung out with a shovel when the sides (of the barrow) came out. His master kicked him for the delay and ‘brought him to the gaol with his hands bound behind him with a silk handkerchief’. Mr Loder, the gaoler, stated that ‘untieing his arm it was so stagnated he could not use his arm to bring it forward’. William and Brabyn dismissed the complaint and gave the man to another master. A similar case was heard later that month with a similar result.

The bench was a little tougher on 30 October 1822 when Patrick Smith ‘was submitted for amelioration of sentence’, after having been convicted ‘of the most insubordinate conduct’ towards his master (Roger Connor). William asked the Colonial Secretary that ‘the indulgence intended to have been bestowed on him this year now be suspended’.7 To lose a ticket of leave was a penalty, but not a harsh one. On 6 April 1825 William declined to pass a sentence when a Mr Baldwin said that an assigned convict, Fletcher, had robbed him and been convicted ‘four years since’ and ‘he has also neglected his work, although he has not brought these charges before the Bench’. Reporting this, William explained to Goulburn, the Colonial Secretary, that: ‘The Bench have ordered Fletcher to work for another person until your instructions are received on regard to him’.8 He was benign when the employer had been unreasonable.9

William, or the bench he chaired, inevitably did order floggings. On 14 July 1817, sitting with the other magistrates Cartwright and Mileham, they sentenced William Jones to 50 lashes and to be sent to Newcastle for three years to hard labour for stealing a bullock, which always had been a serious offence, both here and in England. Jones also forfeited all his personal property against claims and had the ‘overplus paid into the hands of the Treasurer of the Police Fund at the Hawkesbury’.10 George Lawford, a free man, was tried for ‘a very aggravated felony and … sentenced by a Bench of Magistrates on 18 October 1820 to three years hard labour at Newcastle’.11 Newcastle, north up the coast from Sydney, was a penal colony within the penal colony, where men mined coal. Bigge thought that convicts being sent to the Coal River ‘is felt, and sometimes dreaded by them as a punishment; and that it succeeds in breaking dangerous and bad connections, but that it does not operate in reforming them’.12 Given William’s belief in rehabilitation, the sentences sound uncharacteristic of him, though the crimes had been serious.

In general the administration of the law ranged alongside religion and education as part of the paternalism which characterized New South Wales society.13 As far as religion was concerned William not only helped what was then the established church (of England), he supported the Catholic church as well and indeed the Presbyterians. On 24 May 1822 he wrote to Governor Brisbane to support the Reverend M. Therry who had ‘applied to me as Senior Magistrate’ for a piece of ground belonging to the Crown at Windsor ‘for the purpose of erecting a Chappel for the performance of Roman Catholic worship’ and that ‘the late Governor [Macquarie] had been pleased to express his approbation of the same’. He enclosed a sketch. It was built.

Four years later, in June 1826, he even-handedly supported a memorial to the Governor from 27 free settlers from the Scottish borders at Portland Head, who had mostly come out in 1802. They had established a church in 1809, but been without a minister for 17 years. One had now arrived, for whom they had built a house. They asked for him to be granted a salary, in addition to the small stipend which they could raise themselves. William certified that he had known the original settlers for upwards of 20 years (a mild misstatement given that 20 years before he had been on his way to trial in England) and that their ‘conduct was worthy the consideration of His Excellency the Governor’.14

Paternalism infused most things that the magistrates did. For example, the Cawdor bench, at the Macarthurs’ Camden estates, was more lenient than most. ‘Yet,’ its historian observes, ‘its hand could fall with great brutality.’ People felt ‘the machinery of justice was a lofty elaborate thing. It was a system of paternalism, in which the magistrates tempered their sternness … with just as much personal discretion as each case … seemed to require’.15 That early on William overstepped the mark is shown by his being reproved on 14 February 1811, along with other JPs, in that ‘he conceived that he could … convict and sentence persons for the illegal distillation [of liquor]’ when such prosecutions could only be carried through at Sydney.16

There is every indication that the views and judgments of William, and his colleagues on the Windsor bench, were paternalistic in many contexts. Unfortunately for our knowledge of his personal views, a printed questionnaire sent out by Macquarie to all magistrates and chaplains in February 1820 so infuriated Commissioner Bigge that he demanded the suppression of the answers. This was on the grounds that they were preempting his enquiry. The 13 questions did indeed, in Secretary Campbell’s words, cover ‘the Comparative State of the Colony’. They were very similar to those posed in opinion polls today and included some which were transparently hopeful of vindicating Macquarie’s social policies over the previous ten years, such as whether attendance at church had been more regular or less so and whether the ‘lower Classes’ were ‘more circumspect in their Conduct’. What would have been revealing were the questions on corporal punishment and on the attitudes and behaviour of the free-born offspring of convicts.17

The majority of magistrates are recorded as having replied. William’s answers would by no means necessarily have been the same as those he later gave to Bigge in person. Thus when Bigge interviewed him about punishment for neglect of work, he answered that it would be ‘100 lashes & to the coal mines [Newcastle] for terms not exceeding three years’.18 Asked if he approved of that, he replied: ‘If Newcastle was so situated as that the convict could not escape, I should think it an excellent place of punishment’, adding ‘I think that the Punishment has salutary effects upon those who return’.19 The fear of pain was always a part of the penal system. However, William had long shared Macquarie’s beliefs and may have deliberately been saying what Bigge wanted to hear. In a later memorandum he recorded that ‘Severe punishment only hardens them [i.e., convicts]’.20 This was a view later shared, for example, by the chaplain at Norfolk Island, the Reverend Thomas Atkins, who believed that the lash ‘merely brutalized and hardened the prisoner’.21

William’s punishments for assigned females were lenient. In June 1819 one of his own servants, Ann Keogh, most unusually, came up before him on the bench, accused of being drunk and of stealing articles belonging to Rebecca Cox, immediately after her death. Keogh was sentenced to six months at the Female Factory.22 The Female Factory at Parramatta was not exactly a prison, but more like a workhouse to which women who had offended, were refractory or were pregnant were consigned. It was too crowded for all the women to live in and many were boarded out in the town, sometimes turning to prostitution. William also sent one Anne Walker there, on 29 April 1820, for absconding from her husband after meeting one James Anderson in a public house and going to live with him. The background to this was that the woman was a convict, but allowed to live with her husband. Anderson, being a free man, was only fined.23

The intricate domestic situations with which a magistrate had to deal are further shown by a case heard on 7 September 1824, when the bench listened to a statement from Thomas Wright, relating to his wife Anne Wright, alias Ann Hubbard. Thomas had ‘the honor to inform you that the said women is resident in this district, having a certificate of her freedom, but is now under Bail to appear at the Quarter Sessions to a answer to a charge of Felony’. He added that ‘the child [she] has with her has been adopted by her and does not belong to her husband, but to one Mr Dillon, a man with a large family’.24 Today the story would be sensational tabloid material. Such domestic situations were further complicated if one partner in a marriage was a free person, like Anderson, while the other was a convict. In this situation the convict was permitted to live with the free person, who effectively acted as a guarantor.

The Female Factory at Parramatta – magistrates sent recalcitrant women convicts there (National Library of Australia, ref NK/12 47)

Being superintendent of the government labourers in the District of the Hawkesbury involved deciding on the assignment of convicts to private masters sent to the district from Sydney, normally in batches. The register of the Colonial Secretary’s letters shows how frequent this became, as more and more convict transports arrived. Peace in Europe brought unemployment, a surge in crime in Britain and sent an increasing – in fact unmanageable – number of convicts to New South Wales. Commissioner Bigge commented that ‘in perusing the list of persons to whom mechanics have been so assigned, I find them to consist either of the magistrates or of the officers of the government’.25 He might well have enlarged on this. The settler complainants certainly did.

This had not been Macquarie’s intention. At the start of his vice-regal rule there had been a serious shortage of convicts available for assignment. On 24 December 1810, after the transport Indian docked, the Governor’s secretary, John Campbell, wrote to the magistrates saying that it was ‘totally impossible for His Excellency the Governor … to meet the third part of the demand [for assigned convicts]’. On 18 June 1813 he wrote to Samuel Marsden and Cox, as magistrates, ordering that the distribution of stockmen was to be made ‘by ballot and none but industrious and deserving Persons or such as have fair claims to such indulgence shall be admissible to the benefit of the Ballott’.26 Ballots were frequently invoked, being drawn at Windsor for the entire Hawkesbury district, where William evidently considered himself to be an ‘industrious and deserving person’, although less conspicuously so in the early days than later on, when more prisoners arrived.

The Cox family, father and sons, had already received assigned convicts as part of their land grants, starting in 1804. William himself never received large numbers at any one time, acquiring men and some women in dribs and drabs, particularly after the ending of the Napoleonic Wars. Thus on 5 February 1816 William received two from the Ocean and on 18 October that year the Governor directed that three named men be sent to him. On 21 March 1817 he received three of a total of 25 sent from the Sir William Bensley. Whether by coincidence or not, this was three days before he was despatched by Macquarie to explore the Lachlan River from Bathurst. When the number of convicts arriving quadrupled in 1817 and 1818, and Macquarie was hard put to find employment for them, it was more understandable that William got the men he wanted – who were of course primarily ‘mechanics’. On 28 September 1819 Cox again headed the list for Windsor with three men assigned to him.27 By 1819 the number of convicts he employed ‘free of expense to the Crown’ was 86; by 1821 it totalled 104.28 In 1822 the convict indents at the Records Office in the Rocks show he was employing 128.

An analysis has been made of those convict indents of 1822. A sample of one third (actually 48) of the 128 employed was taken. It is not always easy to reconcile names on a later muster with arrival records and with declared job skills. Only 38 could be so identified. Of these, two belonged to government clearing parties working on William’s estate and three were free men or women. Of the 33 remaining, only 13 were servants or labourers, while 20 had skills useful to the estate, including farm men, stable boys, a carter, seamen and a waterman, plus a gamekeeper. Even if an indoor servant and two seamen are excluded, the total of skilled men was still above 50 percent. The wheelwright at Clarendon was a free man, who chose to work for William. So did at least three others, who were free by servitude, plus three ticket of leave men. This route towards emancipation had closely engaged William, ever since the building of the mountain road.

Macquarie defended Cox to Bigge, saying that those ‘who have been useful servants to the government … have surely a prior claim to men who had not been employed in public service’. As recounted earlier, Bigge himself was critical of the rewards given to some men who worked on the mountain road, in at least one case unfairly, and followed this by paying William a very backhanded compliment when he commented on the giving of tickets of leave:

It is to this influence that is attributed the success that Mr Cox has met with in his improvement of the convicts that were placed under him. Men who had been rejected by others … have willingly entered into the services of Mr Cox, and worked for him industriously, under his promises to obtain tickets of leave, or emancipations for them.29

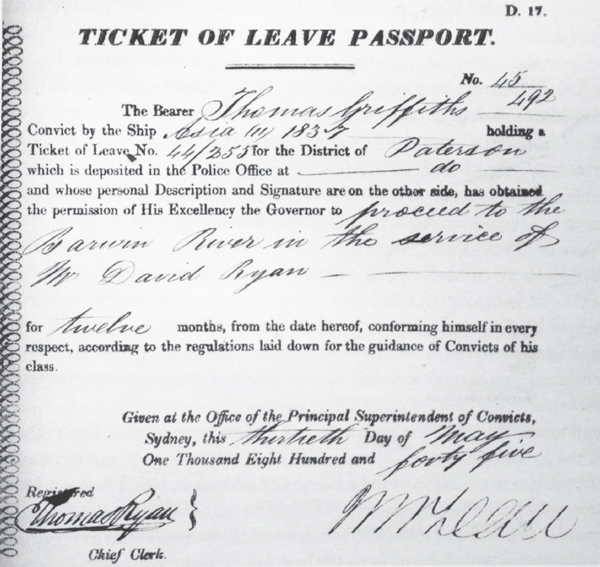

A ticket of leave – the vital pass that enabled a convict to work on his own account

This was indeed a part of the secret of William’s success in dealing with convict employees, though hardly the whole of it: his personality did the rest.

William continued to seek special favours long after Macquarie had left, such as when he asked the new Colonial Secretary, Alexander McLeay, to find him a teacher for his children. On 30 July 1827 he asked for a Robert Turner, belonging to the town gang at Windsor, to be transferred to him for a period ‘as I stand very much in need of a man of his description … he is either a brickmaker or has been accustomed to work in a brickyard’.30 This demand was in spite of the skill being in short supply. Bigge had noted six years before that there were only 17 brickmakers in the entire colony. He commented further that:

Cox got men transferred from working on the roads and obtained services from them gratuitously, which other persons could with difficulty obtain, and must have paid for. Evidence … is very pointed upon this subject and has not been denied by Mr Cox.31

Not surprisingly, William’s skilled workforce aroused envy. John Blaxland was asked by Bigge: ‘Do you know any other persons who have succeeded in obtaining mechanics?’ He replied: ‘I have heard that Mr Cox of Clarendon, Mr Fitzgerald … at Windsor, Mr Meehan, Mr Wentworth’. Blaxland complained that of four he received himself from the Three Bees two were ruptured, one lame and the other incapacitated by old age.32 Samuel Marsden told Bigge that convicts came already assigned to individuals, including ‘To Mr Cox, several’, in spite of having benefited himself. 33 A. G. L. Shaw comments that ‘Only about two dozen “superior settlers” could employ mechanics full time … Marsden had ten, Macarthur was “reasonably satisfied” and so were Cox and D’Arcy Wentworth, though Jamison, Bayly, Blaxland, Howe and Dr Townsend had been aggrieved’.34 D’Arcy Wentworth was similarly accused of misusing his position as a magistrate. Neither side fooled Commissioner Bigge.

At the same time, William was being kept extremely busy at Bathurst, having become a fully accredited expert on expeditions. A short summary of the Colonial Secretary’s correspondence gives an idea of what he was involved in, both at Bathurst and on the Cumberland Plain. In 1816 he constructed a new ‘Western Road’ from Parramatta to Emu Ford, improving access to the mountain road, where he erected new buildings at Springwood. He dealt with an outbreak of hostilities between Aborigines and settlers. He supplied bricks for the new church at Windsor, one of the colony’s most substantial and architecturally notable buildings. On the other side of the mountains he was administering and provisioning government road workers at Bathurst, an activity which continued in 1817.

In March 1817 William was sent by Macquarie to explore the Lachlan River, as already mentioned, and thereafter was responsible over a period of a year for equipping the surveyor John Oxley’s expeditions. It was all very well ordering Mr Cox on 14 June 1817 to have articles such as ‘8 gallons of spirits, 40 lbs sugar, 4 lbs tea, 6 cotton shirts … conveyed to the Depot on the river Lachlan’ for Oxley’s ‘Journey of Discovery’.35 But William had very limited resources and the demands must have seemed incessant. On 29 October 1817 the Colonial Secretary gave more instructions to the Commissary to send stores for ‘the intended expedition to trace the course of the Macquarie river in the country west of the Blue Mountains’. These were for 10 persons, the stores to be sent to Parramatta to be delivered to Mr Cox at Clarendon, ‘he having undertaken to forward them to Bathurst for the Party’.36 Oxley was awarded £200 for this exploration.

The next year the surveyor was asked to try again, with an expedition which began on 4 June 1818. Macquarie reported to Bathurst that ‘If Mr Oxley and his former Companions can be again induced to embark in it [following the course of the Macquarie River] I feel it will afford the best hopes of a satisfactory result’. The Governor thought the river might lead to a great inland sea. This inevitably involved William in organizing the equipment and supplies. The deputy commissary general, Mr D. Allan, was told to send rations for 15 persons for 24 weeks – for example, 2000 pounds of flour, 90 pounds of tea and equipment including a tent, 4 frying pans, 15 suits of slop clothing and 15 pairs of blankets. These were to be ‘packed up and sent off as soon as possible … to be forwarded from thence [Parramatta] by Mr Cox’. On 15 April Allan was told to send more articles ‘being immediately required’ for Mr Oxley’s expedition. Responsibility for the completion of such constantly repeated, very detailed, orders rested with William at a time when Bathurst was only a tiny settlement offering very few facilities. This time Oxley took 12 men, two boats and 18 horses. The horses were important, which explains William’s problems over horses generally, described below. At the same time, in 1817 William himself was preparing to explore the Macquarie River further. Even for a man of William’s organizational ability, this must have been a strain. Obviously he had assistance from supervisors, notably Lewis, who was now on the government payroll. All these demands on his time must have been exhausting and that he carried them out puts the subsequent convicts’ complaints against him in perspective as petty and often malign.

Such constant activity continued until his commission as commandant was revoked by Macquarie on 23 August 1819. The complaints only surfaced more than a year later, on 1 December 1820, when William was summoned peremptorily by Bigge to answer questions about the execution of the Bathurst road, about buildings at Bathurst, the employment of government men and the conveyance of stores to Bathurst ‘by you and one Richard Lewis’, also the receipt of government stock from the public herds. Lewis had been a superintendent in building the Blue Mountains road and in 1815 had been appointed by the Governor ‘to be a Superintendent in the new discovered country to the westward of the Blue Mountains, under the orders of William Cox Esq, with a salary of fifty pounds sterling per annum and the usual indulgences’.37 Bigge seems to be unaware that Lewis held an official post. He was not always as well informed as his assistants might have kept him. Lastly he cited ‘the promises made by you to several convicts of obtaining tickets of leave … in consideration of certain services performed’.38

The origin of these accusations was a short letter to Bigge, dated 2 August 1820, from Charles Frazer, the Colonial Botanist, who had visited Bathurst when William was superintendent in 1818.39 He accused Cox of having misused his position as commandant at Bathurst, telling Bigge that, when superintending the Bathurst road, Cox had procured an extravagant number of pardons and had defrauded the government by misappropriating government material and labour.40 In fact William, even if he had used government facilities himself, had usually been fairly meticulous in accounting for what he had done. Thus in a three page letter to Macquarie on July 1818 on the state of the settlement, he reported in his neat carefully spaced writing, on the arrival at Latt 31.49.40 Long 147.52.13 of Oxley’s party. ‘I immediately made preparations for leaving Bathurst, having previously had inventories taken, horses tools etc.’ He gave details of horses, cash receipts books and rations, also enclosing ‘for Your Excellency’s perusal’ a list of 16 convicts with ‘their claims for remission of sentence’ and went on to explain the state of crops and the need ‘to repair the [mountain] road from the 16th mile to the 21st’.41

This sort of evidence of William’s stewardship is absent from a book on the evidence to the Bigge reports by John Ritchie, in a chapter headed ‘Roguery’ and featuring ‘Conduct of William Cox’. His collection of convicts’ complaints is editorially heavily weighted against William, despite the author saying in an introduction: ‘Paternal, yet politically radical, Cox earned the reputation of being a humane employer and magistrate’. Ritchie then recites the allegations.42 Quite apart from its having taken Frazer two years to draw attention to the complaints, all his accusations were hearsay and six out of eight do not stand up to examination, although two were potentially serious. Thus William Price’s evidence states, ‘I have never received any payment from Mr Cox since I got my Ticket of Leave, but I was in debt to him’. Evidently William had advanced him money, hardly a condemnation. Patrick Hanigaddy had wanted William to sign a petition to the Governor for land, but William had refused saying he had too many petitions. Elijah Cheetham was contesting methods of payment by another man accused by Frazer, named Fitzgerald, which were totally irrelevant.

The most bizarre accusation was the complaint of Richard Kippas. He was a life prisoner who worked for William, who he said ‘allows me £40 Per Annum. He pays me in Property and in money. I now work at Wheelwright’s business and received my emancipation six months ago.’ The pay was almost triple the official rate of £14 a year, but Kippas said he was annoyed that William had not given him a pass, which he had given to several others.43 Earlier he had most unusually not been punished after an escape attempt and went to work for William at Bathurst. In other words, he had of his own free will continued to work for William after achieving emancipation. The complaint by John Emblett, William’s groom, was similarly farcical. He had been recommended for liberty by William, but granted first a ticket and then emancipation by the Governor, not by Cox.

Thomas Smith’s complaint was one about which Ritchie does not appear to have checked the relevant government orders, which illustrate how the system worked at Bathurst. Smith had worked for William in 1816 and in 1817 with bullock carts and told Bigge, ‘I don’t know whether they belonged to him or to the Government’. But on 3 February 1816 Mr Rowland Hassall, the commissary superintendent at Bathurst, had been instructed that ‘William Cox Esq having undertaken to find conveyance for the Provisions and stores required on the part of Government at Bathurst’, he should provide William with ‘ten strong young bullocks [as working oxen] for such conveyance of stores and provisions’ in part payment.44 Again, on 25 October 1817 and in February 1818 the Colonial Secretary’s records show William being issued with oxen in ‘part payment for the carriage of government stores and provisions to Bathurst’.45 Smith’s real grudge was against Macquarie. He said that William had given him a pass and that ‘on presenting it to the Governor he [Macquarie] tore it, saying it was of no use and that he would not have people going about the country with a pass’.46 This sounds unlikely, even though Macquarie could be both imperious and impetuous. Overall, it is understandable that William complained so bitterly to Bigge about labouring ‘amidst a den of thieves and a nest of hornets’.

The only serious accusations came from Blake and Byrne, of which Macquarie testified he had received no complaint, as explained below. Both men nourished a grievance against William because he had accused them of poisoning government horses – of which they had been acquitted, the horses being considered to have ‘died of poor condition’.47 This was in the context of providing horses for Oxley’s expeditions. William had been under pressure for many weeks in 1818 over provisioning Oxley’s expedition into the mountains and horses were in short supply, although the two horses were not intended for the surveyor. William told Bigge that ‘they were bought for Govt to work a two horse cart at Bathurst’. He remained ‘convinced in my own mind that these two men [Blake and Burne] were the cause of the death of the two horses’.48

Blake also told Bigge that a stockyard of two acres had been erected by William, who had sold it and a brick hut to the government, the hut having been built by a government employee named Brown. This was presumably the one at Crooked Corner. William was alleged to have used the stockyard for his own sheep. He also had a house, sheepyards and stockyards built by government men. Then again, Cox and Lewis had used government horses and bullocks to draw a cart to bring provisions from Springwood to Bathurst ‘to save their own’. In reality they were paid for the hire of the cart with cattle from the government herds and William had been ordered to build the stockyards, for which he was paid £49 17s 6d. 49

In total Bigge gave William the evidence of 33 people to read. His reactions to some of it were intense. He pointed to the Bathurst Book of Expenditure, which tended ‘to refute the Ill grounded complaints that are made by a Sett of designing and malicious men, thereby to injure me because as a magistrate I have been obliged to keep a strict watch over their Conduct and punish it when required’. He considered that ‘as a free man James Blackman [the Lawsons’ supervisor] stands pre-eminent in the mis-statements … instigator of the others’. When William wrote again to Bigge on 20 January 1821 he was unusually vehement, reminding the Commissioner of his many years service as magistrate and the efforts he had made for the government.50 He followed this up with a vigorous rebuttal of various convicts’ accusations that he abused his office when superintendent of Bathurst, saying, as quoted in the Foreword: ‘There is not a magistrate in the Colony who has given as much of his time to the business of the Crown & the public these ten years past as myself’.51

The evidence does suggest that William had been maligned. The use of the bullocks and carts had been repeatedly authorized by Macquarie. He had not sold a stockyard to government: he had been paid to build it at Crooked Corner, although it is probable that he also used it for himself. 52 But the real crux lay in William’s accusations over the horses. Both Blake and Byrne revealed personal grievances against him. Blake’s included that: ‘Mr Cox promised me an emancipation in the year 1816, if I would go to his stockyard & mind his sheep’. He had received emancipation, but not from William, as had John Emblett. Byrne had been sent to mark out 56 miles of road from the Lachlan River to the Limestone Rock but ‘Mr Cox never paid me for the work’. He told Bigge about a black horse named Scratch that ‘had been employed by Mr Cox in drawing his Caravan was employed in taking down wool from Bathurst. He had a Government mark upon him.’ But Scratch had been acquired legitimately for the Blue Mountains road in 1814. In his 30 January letter William said, ‘The old horse Scratch was the one allowed me for my caravan’.

Byrne continued about a team of government bullocks bringing up provisions for Oxley’s expedition and taking down a load for Lewis.53 But on 3 February 1816, one of the occasions mentioned by Byrne, the commissary superintendent, Hassall, who seems to have been assisted by his son, had been told that William should receive bullocks in part payment for the conveyance of stores.54 On 5 October 1816 the Deputy Commissary (the son), had written to the storekeeper at Bathurst, Thomas Gorman, instructing him to issue to ‘Wm Cox Esqr’ or his order, ‘fourteen cows and five oxen, being the balance due to him for carriage of provisions and stores from Parramatta to Bathurst’. Furthermore, Gorman had been told: ‘you will be careful to see the above cattle branded with Mr Cox’s brand before they are delivered’.55

Macquarie, when questioned by Bigge about ‘Mr Cox’s conduct at Bathurst’, defended William. He emphasized over the stockyard question that: ‘he could not credit the Charge as now made. If any Cattle were drawn improperly by Mr Cox, it must be attributed to the neglect of the then Superintendent of the Government stock.’ Protecting himself, he added, ‘The Governor does not however feel himself called upon to explain imputations against Mr Cox or any other person’.56 However, it had been at Macquarie’s direction that William had been paid in cattle and oxen.57

William spiritedly denied any wrongdoing on his part, whilst claiming that the storekeeper Gorman had been a rogue. Bigge picked up on this, criticizing him for recommending Gorman, when ‘Thomas Gorman, who acted as storekeeper to the Bathurst road party, and afterwards at Bathurst appears in the language of Mr Cox … to have been “a consummate villain”’. William had earlier described Gorman as ‘not equal to the task’ and had asked Macquarie for a replacement, unsuccessfully. He now protested that he did not appreciate what Gorman had been doing: ‘I perfectly understand the mode of common accounts, but am unacquainted with Commissariat Terms or Accounts’.58 Bigge then devoted a whole page of his parliamentary report to criticism of the temptations created by ‘the system upon which Mr Cox had been suffered to conduct the government works, and the issues of provisions at Bathurst’: in other words, which Macquarie had forced on him.59 Part of the Commissioner’s private instructions from Lord Bathurst had been to investigate the alleged extravagance of Macquarie’s public works. This fitted the hidden agenda.60

Referring to Byrne and Blake, the only convict complainants he appears to have taken seriously, Bigge wrote: ‘It must be observed, that Mr Cox had sent these men to be tried before a criminal court on a charge of poisoning the horses … a charge of which they were acquitted, but of which Mr Cox still thinks they were guilty’. Both were acting as superintendents of farms and ‘were much trusted and commended by their employers’. But Bigge did refer to the ‘difficulty of obtaining concurrent testimony respecting the character of convicts’.61 A logical conclusion is that William had lost his temper with Byrne and Blake over the horses dying. Bigge failed to understand that they were not for Oxley’s expedition, but there was a shortage due to Oxley’s needs. The other accusations were not pursued. It is likely that, over the matter of the stockyards, William had been mixing private and government business, as he often did. No official action was ever taken against him as a result of the complaints.

Overall, when surveying William’s contribution to the governance of the colony in those years 1816 to 1819, when he was the administrator at Bathurst – the only period in his life in which he served as a representative of the Governor – he unquestionably gave a very great deal more to the colony than he took. But, as elsewhere throughout his life, he did have what can most politely be called an eighteenth-century attitude to the perquisites of office. Nor did he cease acquiring land.

The 1819 list of grants from 1812 to 1821 shows that William obtained two grants of 820 and 200 acres at Bringelly (Mulgoa) on 8 October 1816 and a further 760 acres there on 18 January 1817. His sons George got 600 acres there on 8 October 1816 and Henry 400 on 18 January 1818, while William Jnr was allotted 800 acres at Melville and Henry 200 at Minto.62 These were all in the County of Cumberland, south of the road from Parramatta to Emu Plains. Whether the Bringelly plots were adjacent is not clear, but it must be highly likely that they were and they underline the ‘family business’ concept which William pursued. Macquarie was generous to the Cox family, and to others, no doubt partly because it furthered his idea of allocating all the land on the Cumberland Plain before making grants beyond the mountains. He also granted land to James Cox at Fort Dalrymple in Van Diemen’s Land, to which James had been permitted to move with one convict servant in 1819, where he eventually formed his own Clarendon estate. Whatever disadvantages representing the Governor at Bathurst had involved, they did not halt the Cox family enterprise.