I think I am safe in saying that the members of the Board … consider the gold medal for public service as easily the most important prize of the year. I feel certain that they share my belief that my father so regarded it. Journalistic public service was my father’s passion.

—JOSEPH PULITZER II, PULITZER BOARD CHAIRMAN, 1940–1955

For those who follow the journalism Pulitzer Prizes each year, mention of the Public Service Gold Medal probably conjures such famous work as the

New York Times’s Pentagon Papers coverage and the

Washington Post’s Watergate reporting, honored in 1972 and 1973, respectively. In a way, those two reporting efforts rise like twin peaks above the majestic range of great stories whose news organizations have been honored through the twentieth century. At the beginning of a new century, exactly thirty years later, two more summits stand out: the

Times’s response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the

Boston Globe’s remarkable revelations about the sexual abuse of young parishioners by Catholic priests. Taken together over the one hundred years of prizes, though, the entire succession of gold medals has dramatized—and often seemed to predict uncannily—the course of national events. Indeed, the famous 1960s-era definition of the American newspaper as “a first rough draft of history”—usually attributed to the late

Post publisher Philip Graham

1—could just as well describe the work honored with the Public Service Prize.

The first gold medal honored the

New York Times for its coverage of World War I, marking America’s turn from isolationism. Three years later, one recognized a newspaper’s exposé of scam artist Charles Ponzi that forecast, in a way, the nation’s economic malaise of the 1920s. As the Great Depression began, Pulitzer Prize–winning publications unearthed cases of municipal corruption and other crimes and called attention to the heroic efforts of farmers to counter the Dust Bowl’s effects. In a campaign by the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch to clean its hometown’s air—the public service winner in 1941—one sees early signs of the environmental movement that would eventually sweep the country. The old

Chicago Daily News won in 1963 for reports on birth control services, an early look at one of a number of social issues getting attention from the press. And with the Pentagon Papers and Watergate disclosures, of course, a new era of public skepticism about government arrived. Perhaps scandals described in more recent gold medal stories—the Catholic priest exposé (2003), mismanagement of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (2008), and rampant government spying on Americans (2014)—will be seen one day as predictors of another age of reforms stemming from public attention brought by the media.

Often the Pulitzer board’s selection recognizes a news organization’s courage in blowing the whistle on those with the power to harm the messenger. The 1927 prize acknowledged Ohio’s Canton Daily News, whose editor Don R. Mellett was murdered for his criticism of local politicians too close to a criminal gang. In 1953, the board chose the Whiteville News Reporter and Tabor City Tribune, two North Carolina weeklies that took both fiscal and physical risks by exposing a local revival of the Ku Klux Klan. A case in 1978 involved a small California weekly, Marin County’s Point Reyes Light, which took on the locally based Synanon cult. The paper intensified its fight after a lawyer who opposed Synanon was bitten by a rattlesnake that group members had stuffed in his mailbox.

Of course, the year’s gold medal winner hasn’t always glittered so brightly, especially in the early years when the Pulitzer Prize was struggling to establish an identity. The 1919 Public Service Prize to the Milwaukee Journal hailed the paper’s opposition to “German-ism” during World War I when the Journal argued for schools to stop teaching the German language, for example. Some other early public service honorees basically submitted a range of their best stories without a central theme. (Newspapers also slowly learned what qualities it took to produce a gold medal winner. In 1929, the Cleveland News submitted the work it had done to simplify its headline styles. It lost.)

Ask winners about the value of awards like the Pulitzers and they will toss in a few caveats. “We don’t write for prizes,” says

New York Times publisher Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., whose newspaper has nonetheless won five gold medals between 1918 and 2004. “We are delighted to win them but our journalism is aimed at enhancing society, not winning prizes,”

2 he reiterates.

The cult of self-congratulation that some see in the proliferation of press awards, and to some extent the Pulitzers, certainly has its critics. Among those who find flaws in the Pulitzer process itself, few had sterner reservations than Ben Bradlee, who became a celebrity after the

Washington Post’s Watergate Pulitzer and the

All the President’s Men phenomenon. In a 1995 autobiography the then-seventy-five-year-old editor declared that “as a standard of excellence the Pulitzer Prizes are overrated and suspect.” The opinion, he said, is based on observations from his service on the Pulitzer board from 1969 to 1980: “It is this board, political and establishmentarian, that clouds the prizes. Mind you, it’s better to win them than lose them, but only because reporters and publishers love them. In my experience, the best entries don’t win prizes more than half the time.”

3 In later years, though, he found the gold medal to be relatively pure. “The Public Service Prize is what it says it is,” Bradlee claimed. “The Public Service gene is very strong in all good journalists.”

4The McClatchy Company has long prided itself on having that genetic structure. Before its 2006 purchase of Knight Ridder, McClatchy boasted of having five Public Service Prizes, and the Knight Ridder acquisition added significantly to its stable of papers with Pulitzer-winning traditions. “The Pulitzer Prize, particularly the Public Service Prize, resonates in terms of recruiting talent,” says Gary Pruitt, who at the time was McClatchy’s chief executive officer. “Those things don’t happen by accident; they’re a reflection of commitment of resources on a sustained basis.”

5A Statesman for the Press

The wide appeal of the prizes would have pleased Joseph Pulitzer, who had what he called “the germ of an idea” in August 1902 for a system of awards to honor the best of both American journalism and arts and letters. At Chatwold, his secluded summer retreat on Maine’s Mount Desert Isle, he dictated his thoughts: “My idea is to recognize that journalism is, or ought to be, one of the great and intellectual professions; to encourage, elevate, and educate in a practical way the present and, still more, future members of that profession, exactly as if it were the profession of law or medicine.”

6FIGURE 2.1 The Chatwold estate near Bar Harbor, Maine, with its “tower of silence,” right. At Chatwold, Joseph Pulitzer developed the idea for the Pulitzer Prizes. Source: Used by permission, St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Two years later, he inserted a $500,000 bequest to Columbia University for the prizes into his will. It was part of a $2 million overall gift that also endowed a journalism school at Columbia. In 1912, the year after Pulitzer died at age sixty-four aboard his yacht Liberty in Charleston Harbor, the university got the journalism school running. That established the framework, under the terms of the will, for a system to consider entries from 1916 for the new Pulitzer Prizes. The first prizes were awarded at Columbia’s commencement in June the next year.

The Pulitzer Prizes in journalism were a revolutionary notion. Not that the thought of a major awards program was so unusual. Sweden’s first Nobel Prizes had been awarded in 1901, just before Joseph Pulitzer dreamed up his own system of awards. The Nobels were globally celebrated as a way of honoring scientific and literary achievements and of furthering the cause of peace. And in 1896, the modern Olympic organization had resurrected the ancient Greek Games, bestowing gold, silver, and bronze medals on the world’s sports heroes. (Indeed, preparations were heating up for the 1904 Olympics in Pulitzer’s old hometown of St. Louis, where the Hungarian immigrant had settled in 1865.)

What was outlandish about the Pulitzer Prizes was the thought of praising journalism at the turn of the century. Newspaper work was a suspect occupation at best as practiced by most of the publications of the day. That had certainly been true at Pulitzer’s own New York World as recently as the late 1890s, when it was the epicenter of that shameful period of press history known as yellow journalism. That term for rampant sensationalism, in fact, had gotten its name from one of Pulitzer’s many World innovations, the first comic strip, known as “The Yellow Kid.”

Joseph Pulitzer’s career had started brilliantly. In 1878 he had merged two small papers into the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which was a hugely successful operation when he left its day-to-day management five years later and moved to New York to take over the

World. At both papers he promoted investigative reporting and campaigns against government corruption, part of a broad strategy designed to appeal to the masses of average readers. The approach produced handsome profits and Pulitzer’s ability to spur prolific readership gains by combining hard-hitting journalism and public promotions became a model for other publishers.

7One such Pulitzer promotion made the World the leader in raising money for a pedestal on Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor, without which France’s gift of a dramatic “Statue of Liberty” would have remained only a dream. Its erection had been unpopular among wealthy New Yorkers, but the World taunted the rich for their unwillingness to finance the construction and promised to publish the name of every contributor, no matter how small. Circulation soared as a result.

Then came a darker period for Pulitzer and journalism. When an all-out war for New Yorkers’ pennies broke out among newspaper publishers, Pulitzer reacted desperately in an effort to keep his circulation high. Competing with William Randolph Hearst at the

New York Journal, among others, Pulitzer’s

World carried absurdities and exaggerations in the news pages. It was a nasty, no-holds-barred conflict as well, particularly when Charles A. Dana of the

Sun turned on Pulitzer personally and labeled him “Jewseph Pulitzer” and “Judas Pulitzer [who has] denied his race and religion.” (It was a thinly veiled attempt by Dana to turn both anti-Semitic readers and Jewish readers against the

World.) The proliferation of sensational news accompanied chauvinism of the worst kind, winning the

World, the

Journal, and other papers a place in journalism infamy for having helped foment the Spanish-American War.

Pulitzer was pained by the descent of his papers even though he clearly had allowed it by sacrificing his principles to hold onto circulation. After the war he quickly restored sanity in the newsrooms. But he was tortured in other ways. His health, never very good, deteriorated seriously. He became nearly blind and extremely sensitive to noise and suffered from debilitating nervousness and depression.

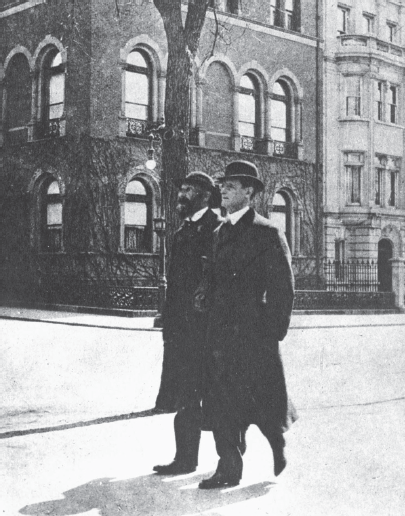

FIGURE 2.2 Joseph Pulitzer I, nearly blind, strolls along Fifth Avenue with oldest son Ralph of the New York World. Source: Used by permission, St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

He had also become an absentee publisher, controlling from afar the activities in the twenty-story, gold-domed

World building with which he had graced lower Manhattan. (As the 1880s ended, it was the tallest skyscraper in the city, eclipsing Dana’s humble

Sun offices across the street.) Pulitzer began spending nearly all his time at Chatwold—equipped with a stone “tower of silence” where he could concentrate deeply—and his other homes in the United States and Europe, and eventually aboard

Liberty.

He became a statesman for the press, championing the newspaper’s role in preserving democracy by giving readers all the facts. In an article for the North American Review, composed the same year as his will, Pulitzer wrote:

Our Republic and its press will rise or fall together. An able, disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and the courage to do it, can preserve the public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery. A cynical, mercenary, demagogic press will produce in time a people as base as itself.

8

In those later years, he made sure his own papers—the Post-Dispatch and the World—followed that creed. The “platform” he wrote when he stepped down from the editor job in St. Louis proclaimed that the paper should “always fight for progress and reform” and “always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers.”

Another Pulitzer comment presaged, in a way, what the

Washington Post was to do almost sixty-five years later in winning its 1973 gold medal. A 1909 letter he wrote to the

World editorial page editor Frank Cobb expressed Pulitzer’s thoughts on Theodore Roosevelt’s support of the Panamanian revolution, which preceded the completion of the Panama Canal by American industry. The

World had argued that $40 million in improper payments were made along the way: “If this is to be a government of the people, for the people, by the people, it is a crime to put into the hands of the President such powers as no Monarch, no King, or Emperor has ever possessed. He has too much power already…. I would rather have corruption than the power of one man.”

9A near recluse as his maladies intensified and he entered his mid-fifties, Pulitzer contemplated his mortality. He began envisioning a personal legacy—one that would recognize his lifelong devotion to newspapers and the role he believed they should play in democratic society. The spirit of philanthropy was in the air, stirred by vast gifts to benefit the public good from industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, who was very public about the need for the rich to give back to society. But Swedish munitions mogul Alfred Nobel may have seemed a better model to Pulitzer, providing both inspiration and a model for his benefaction.

10Some historians have suggested that Pulitzer and Nobel indeed shared a hidden motivation for their desire to take on worthy causes. According to this view, the Nobel Prizes designed by the inventor of dynamite and the blasting cap were sparked by a macabre happenstance in 1888. That year, some French newspapers mistakenly reported Nobel’s demise after they confused him with his brother Ludvig. “Le Marchand de la Mort Est Mort,” one paper proclaimed: “The Merchant of Death Is Dead.” Seeing how he was fated to be remembered, these accounts suggest, a horrified Nobel changed his life overnight—much in the manner of Dickens’s Ebenezer Scrooge on that ghostly Christmas Eve. Eventually, by devoting part of his fortune to the commemoration of great world achievements, he saved his reputation for posterity.

11 Whether Pulitzer acted out of a need for redemption for earlier career sins is likewise open to speculation. But he also designed his prizes to be established after his death and made them part of a grand benefaction, in combination with a bequest he envisioned as creating the first university-based school of journalism. (As it turned out, the University of Missouri’s journalism school opened in 1908, giving it that distinction by four years.)

Columbia had been Pulitzer’s first choice as a home for the journalism school and the awards, largely because of his love of New York and its place as the center of the publishing universe. (He had briefly considered Harvard, until that school responded coolly to the idea.) Pulitzer’s will dictated that the awards in journalism and letters would exist “for the encouragement of public service, public morals, American literature, and the advancement of education.” In his negotiations with Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler, Pulitzer was particularly insistent on giving control of the prizes to a special new board that would be dominated by newspaper editors. The group originally had the name Advisory Board of the Columbia School of Journalism, even though its main responsibility was always to be for the prizes.

12 (In 1950 it became the Advisory Board on the Pulitzer Prizes and then in 1979 simply the Pulitzer Prize Board.)

Neither the plan for the school nor the plan for the prizes was popular with Pulitzer’s aides. One of them, Don C. Seitz, suggested a better investment for the $2 million: “Endow the World. Make it foolproof.” There was some prescience in the recommendation. While the paper would turn out some great journalism in the two decades after Pulitzer’s death, it would finally be run into the ground by sons Ralph and Herbert, who sold it to Scripps-Howard in 1931 and watched it disappear. But the deal for the bequest was sealed with Columbia’s president Butler, and the will was signed on April 26, 1904. Columbia was required to prove to the new advisory board that the journalism school had functioned successfully for three years before the money for the prizes would be established.

Including the journalism prizes with related awards to honor American novelists, historians, biographers, and dramatists was a clever stroke on Pulitzer’s part. The association of lowly newspaper work with achievement in fine arts did indeed help elevate the press. The timing was just right, too, for innovations like the prizes and university-based journalism schools. Early in the twentieth century, Pulitzer’s own papers in New York and St. Louis were helping create what was called the New Journalism, turning away from the pure sensationalism and political bias of the past and emphasizing fairness and balance instead. At the same time, the papers launched crusades to right various public wrongs on the readers’ behalf.

The first advisory board contained a handful of powerful newspaper editors and was chaired by Pulitzer’s son, the thirty-five-year-old

World editor Ralph Pulitzer. Only two of the eleven editors or publishers on the board worked outside the Northeast—one from the

Post-Dispatch and one from the

Chicago Daily News. Besides Columbia’s Butler and Ralph Pulitzer, the board included John Langdon Heaton of the

World, Edward P. Mitchell of the

Sun, Charles Ransom Miller of the

New York Times, St. Clair McKelway of the

Brooklyn Eagle, Melville E. Stone of the Associated Press, Samuel Calvin Wells of the

Philadelphia Press, Samuel Bowles of the

Springfield (Massachusetts)

Republican, and Charles H. Taylor of the

Boston Globe. Early on a rule was established calling for editors to step out of the room whenever their own papers’ entries were considered.

The original designations for the annual awards adopted language from the Pulitzer will, including a description of the medal for “the most disinterested and meritorious public service.” The Reporting Prize was for “the best example of a reporter’s work during the year; the test being strict accuracy, terseness, the accomplishment of some public good commanding public attention and respect.” The reference to terseness, long since removed from the reporting description, is worth a chuckle in this day of multipart, multipage entries that sometimes tax even jurors’ ability to get through them.

While the first board was guided by Joseph Pulitzer’s terms and seemed intent on honoring his memory by selecting high-quality winners, it had few submissions to work with in the early years. That was true even though Columbia advertised for entries. The infrastructure that had been designed for the prizes was weak, leaving much of the judging in the hands of Columbia professors. They were assigned to look through entries and pass on their recommendations to the board. In one of his histories on the Pulitzer Prizes, John Hohenberg suggested that Columbia president Butler wanted the faculty to make the final selection of winners, with the board doing the nominating. Hohenberg, who was Columbia’s administrator of the prizes from 1954 to 1976, noted that the journalists of the advisory board soon took charge of the final designation of prize winners. They have never relinquished that task. And as the jury system evolved, smaller panels of journalists eventually took the job from professors.

The length of service on the board was not limited during the early years of the Pulitzer Prizes, and a number of members stayed on for more than a decade. Several strong factions developed over its early decades, opening the board of those years to charges that it was something of an “old boy network.” Ralph Pulitzer’s younger brother, Joseph Pulitzer II, editor and publisher of the

Post-Dispatch, joined the board in 1920 for what was to be a thirty-four-year stay, spending the last fifteen years as chairman. He was a modest man who was generally happy acting as moderator while the powerful editors around the table expressed their opinions. But his devotion to his father’s principles was a beacon for the board, and that grounding in Pulitzer family values continued when his own son, Joseph Pulitzer III (known as Joseph Pulitzer Jr.), took over as chairman after JP II died in 1955. JP Jr. retired in 1986 and left the board without a Pulitzer as chairman for the first time in seven decades.

A Juror Makes a Difference

Almost from the beginning, the Pulitzer boards were steeped in secrecy, which they believed was necessary to allow for a candid discussion of candidates. Until recent years, the board did not identify entries that had been finalists and said next to nothing about the selection process.

In 1985, the late

Los Angeles Times media critic David Shaw, a student of the Pulitzer Prizes and a winner himself, wrote about the power struggles that had played a role in past board choices for prizes and described some of the board’s selections as capricious. But Shaw wrote that in the late 1970s a nine-year maximum term limit and other board-instituted reforms had improved the process. Since then, he wrote, “although some prizes are still won (or lost) for reasons other than journalistic merit—sentiment, tradition, geography, luck—no one man (or group of men) dominates the Pulitzer board today. Voting blocs shift constantly, depending on the issues involved in any particular award or procedural question.”

13Jurors today infuse the Pulitzer process with energy. They view jury duty as an honor—“Pulitzer juror” looks very good on a résumé—and value a networking experience that inspires them to bring their best to the historic World Room. The room is dominated by the ninety-square-foot “Liberty Window,” a blue stained glass representation of Lady Liberty raising her lamp between the globe’s two hemispheres. Columbia received the memorial to Joseph Pulitzer’s Statue of Liberty campaign after the

World building was torn down in the 1950s to improve access to the Brooklyn Bridge.

14Although Howard Weaver first served as a public service juror in 1988—the first of his three times on that particular panel—he remembers the experience as though it were yesterday. “I was just gaga to be there,” says Weaver, then an

Anchorage Daily News editor whose work had been part of a gold medal project about Alaska’s Teamsters Union a dozen years earlier, when he was twenty-five. Now here he was, debating the best public service of the prior year with a distinguished panel of reporters and editors from around the country, faced with the job of narrowing about one hundred entries to three.

In the process of selecting finalists—including the eventual winner, the

Charlotte Observer, for its exposé of the PTL television ministry’s misuse of funds—Weaver was involved in a heated discussion about the publication that would be the jury’s third pick. His position won out, he says. “It was one of those moments when I realized how important the jury work was,” he says. “And I also realized, here’s this kid editor from Anchorage, Alaska, who made the difference. If I’d been slightly less passionate, the nomination would have gone the other way.”

15FIGURE 2.3 Pulitzer Prize jurors in the 2014 judging meet under the “Liberty Window” that dominates the World Room of the Columbia Journalism Building. Source: Used by permission. Photo by Thomas E. Franklin.

The old jury system of passing around “clip books” with paper entries from newspapers gave way years ago to laptops for reading entries—now submitted electronically, of course. However, there is still no formal fact-checking capability within the entry judging system—something that has hurt the journalism Pulitzers over the years. In the worst-case scenario of an undetected Pulitzer fraud, the

Washington Post returned the 1981 Feature Writing Prize of reporter Janet Cooke after it learned that she had made up her story about a child hooked on heroin. Since then, skepticism has played a much greater part in the judging process for both jurors and Pulitzer board members.

But former board member Geneva Overholser, for one, maintains that it would be hard to improve on a Pulitzer selection system that puts the task in the hands of the nation’s top editors, backed by academics familiar with journalism. “I challenge anyone to think of a better way to recognize extraordinary journalism. The record speaks for itself,” says Overholser, a celebrated journalism educator who cites among her own proudest moments her acceptance of the 1991 gold medal for the stories written for the newspaper she edited at the time, the

Des Moines Register. “It’s like that wonderful Churchill statement about democracy being the worst form of government, except for every other form of government.”

16In 2014, the nineteen-member Pulitzer Prize board was chaired by Paul Tash, the chairman and chief executive officer of the

Tampa Bay Times who also chairs the board of trustees of the Poynter Institute, the school for journalists. The Pulitzer board contained editors and publishers from large and small media outlets all over the country, from New York, Miami, and Washington, D.C., to Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Davenport, Iowa; and Dallas, Texas. There was a playwright, a magazine writer, and faculty members from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Pennsylvania, along with Columbia president Lee C. Bollinger and Columbia journalism dean Steve Coll, who is a former

Washington Post reporter and editor.

17When the winners are announced at exactly 3:00 p.m. on the first Monday after the April board meeting, the administrator traditionally steps to a lectern in front of the Liberty Window to “sprinkle fairy dust on people and change their lives forever,” as former administrator Sig Gissler once put it when he presided over the old-fashioned press affair of the type he liked. Within a few minutes of the announcement, a package of information about winners and finalists is made available online.

When word reaches the dozen or so winning newsrooms, of course, cheers go up and champagne corks pop—if editors have learned of a prize in advance or have taken a chance on purchasing bubbly just in case. At many other news organizations, though, the mood is somber as the official word goes to finalists that there will be no prize for them that year.

18 One such “Pulitzer Day” at the start of the twenty-first century was like no other, though. Even as

New York Times staffers celebrated a record one-year haul of seven prizes—including the coveted Public Service Gold Medal—they felt an enormous pang of sadness.

19