CHAPTER 4

The Duet Model

The Duet Model is, unarguably, the best model for students. In this model, Teacher A and Teacher B share everything. Right from the beginning there is a sense that the students are “ours” rather than “yours” or “mine.” Although this model embraces the unique skills and talents that each teacher brings, it does not expect roles and responsibilities to be delineated based on job title. Both teachers fully collaborate to meet the needs of all students.

“Right from the beginning there is a sense that the students are “ours” rather than “yours” or “mine.” ”

At a Glance

Teachers in the Duet Model start by spending time together designing the curriculum for the course. If the curriculum is predetermined, then the teachers review it together, making professional decisions about areas of emphasis and timing. The collaborative process continues as they work to design specific instructional objectives, activities, and assessment tools. The specialist weaves her expertise and the needs of targeted students into the plan they are designing. Planning together requires a significant time investment before the school year begins so that the first day of school finds them ready to present as co-teachers to their class.

Ms. Trenton, a third-year ELL teacher, and Mrs. Ashland, a veteran fourth-grade teacher, have been assigned to co-teach a language arts block together in the fall. Mrs. Ashland’s class will have five students who are receiving English Language services. They are currently functioning on different levels of language acquisition. Ms. Trenton has provided pull-out services to the fourth grade in the past and is somewhat familiar with their language arts curriculum. Their principal has arranged for them to receive two days of stipend money to collaborate in the summer so that they can kick the year off in a highly integrated fashion.

Mrs. Ashland takes the lead in planning by reviewing the current curriculum map and sharing her thoughts about priorities. Ms. Trenton describes the specific needs of the targeted students and suggests areas that will lend themselves well to meeting these needs. They agree that they will use a mixture of co-teaching models, depending on the content and the progress of the students, with flexibility as a key operating principle. The partners look at fiction and nonfiction books that will be culturally sensitive and are available on a variety of reading levels, and discuss writing prompts and strategies that will engage language learners.

By the end of their second planning day, both teachers have a sense of their roles and responsibilities, have brainstormed numerous teaching ideas, and are excited about working together.

Once instruction has begun, Teacher A and Teacher B are usually indistinguishable to students and community visitors. Both teachers take turns with leading the instruction, with supporting individual students, and handling the daily classroom management tasks. An educated observer will notice that the specialist may be more inclined to restate, clarify, adapt, and use specialized instructional techniques than the general educator, but it is usually a subtle difference. The general education teacher may appear to be more knowledgeable about the content, able to add depth to examples, and easily generate acceleration activities. Even with these potential differences, there is still a clear feeling in the Duet Model classroom that this is a shared class.

The Duet Model incorporates many of the other models of co-teaching. Table 4.1 shows the variety of ways teachers using the Duet Model work together throughout the course of a week. Within this plan, the partners have included the Speak and Add Model, the Parallel Model, the Skill Groups Model, the Complementary Skills Model, and have switched the instructional lead several times. This is only possible because they have the time and the skills to communicate regularly and effectively about how to meet the needs of the students in their shared class.

TABLE 4.1: Duet Model Unit Plan

See Appendix A for a detailed explanation of this instructional strategy.

See Appendix A for a detailed explanation of this instructional strategy.

Intense collaboration continues after the instructional phase. Both teachers are involved in assessing all students. This may take the form of turn taking with paper grading, splitting assessment responsibilities based on interests and skills, or sitting side-by-side to grade each student. No matter how the workload is divided, weighty decisions are shared. Consensus is reached so that final grades and reports are viewed by parents and students as a unified decision. Conferencing with parents and students is done by Teacher A and Teacher B, and together they will design the next learning steps for students.

Mr. Hayden and Mrs. Mohagen have recently begun their first year of co-teaching Algebra I. Mr. Hayden, a veteran math specialist, is enthusiastic about developing new skills. Mrs. Mohagen, a highly skilled special education teacher, had some trepidation about co-teaching. She worried about being viewed as an aide by the classroom teacher. But their experience is turning out differently. Mr. Hayden embraces the skills that Mrs. Mohagen has in specially designed instruction. In fact, the differentiation in the classroom is working so well that they have decided to tackle the chapter tests that have been used by the department for the last few years.

After several hours of painstaking work, they have developed a test that allows students to choose which problems to complete, yet doesn’t allow students to avoid challenging word problems altogether. They have formatted the test in a way that will work for the students in their Duet Model class that have visual perception problems and fine motor difficulties. After administering and grading the assessment, Mr. Hayden says “It was a lot of work to design the test, but it worked so well for the students. We’ve decided to keep at it throughout this year and next until we have differentiated assessments that we like for each unit.”

Roles and Responsibilities

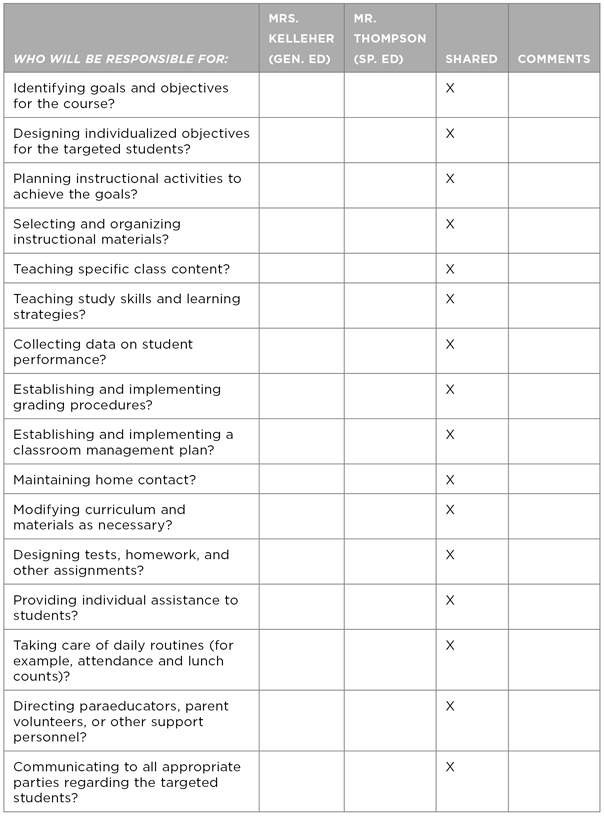

The Responsibilities Checklist (discussed in Chapter Two) for a Duet Model collaboration between Mrs. Kelleher, a general education teacher, and Mr. Thompson, a special education teacher, is shown in Table 4.2:

TABLE 4.2: Collaborative Teaching Responsibilities Checklist—Duet

These two teachers agreed that they would share all of the major responsibilities for their co-taught class. The Duet Model is the only model in which all of the responsibilities on the checklist are likely to be shared. However, in practice, there were many situations where it made sense for one to take a lead role. For example, Mr. Thompson has more extensive experience in writing IEPs. To save time, he generated ideas for student objectives on his own, and then discussed these with Mrs. Kelleher to get her input. Mrs. Kelleher has a wealth of content resources—books, websites, articles, and activities—and so it made sense for her to guide the brainstorming of ideas for teaching the content. But Mr. Thompson has a personal passion for sports and nutrition, so he is likely to take the lead if this topic arises in the curriculum. And Mrs. Kelleher has a daughter who has been diagnosed with visual perception difficulties, so she has learned a great deal about that particular challenge and how to address it in a classroom setting. Together, the two teachers blend their knowledge and skills to provide the best instructional experience possible.

Pros and Cons

In an effective Duet Model classroom, the benefits of co-teaching are maximized. Every benefit described in Chapter Two is present in the Duet Model classroom because both teachers work so closely together in all phases of the instructional cycle. A Duet Model team might very well qualify for what Warren Bennis and Pat Ward Biederman call “Great Groups.” In their book Organizing Genius: The Secrets of Creative Collaboration, they describe Great Groups as people with similar interests who create something together that is not possible on their own. They “can be a goad, a check, a sounding board and a source of inspiration” (1997, 7) for each other that can lead to successful synergy. They work so well together that they create a classroom filled with possibilities and achievements.

What happens in the Duet Model that makes it so powerful? Differentiation is a constant, comprehensive component of instruction. The specialist identifies the needs of targeted students during the initial planning phases. Teachers formulate units with these needs in mind from the very beginning, rather than attempting to integrate these needs after the fact. Day-to-day changes are quickly discussed and agreed on by the teaching partners so that differentiation is flexible and formative. The specialists also brings their unique assessment perspective to the design of projects and products that will provide the team with necessary assessment information. Because the team spends so much time together, it is easy for them to plan for and provide the differentiation students need to be successful.

Professional growth in a Duet Model classroom is extensive. When two teachers work so closely together it is inevitable that they will learn from each other. The general educator gains knowledge about the specialty of his or her teammate. If co-teaching with a gifted education specialist, that knowledge might include simple methods for compacting the curriculum. If co-teaching with an ELL specialist, the classroom teacher might gain knowledge about emphasizing cognates when introducing vocabulary terms. Not only do these new skills assist the classroom teacher in working with targeted students, but these skills also invariably generalize to improving instructional results for all students. Professional growth for the specialist occurs in the content depth and breadth they acquire from working closely with the content expert—the general educator. The pre-service training for most specialists does not delve deeply into any single content area—instead it usually provides a quick survey. The Duet Model experience offers the specialist time and support to expand their content knowledge. This knowledge then becomes transportable, moving with them into encounters they have with students in other co-taught classrooms or in self-contained and resource room settings.

The intensity of the Duet Model results in one major difficulty—time. An enormous amount of time is necessary for the Duet Model to work: time for two teachers to plan together, teach together, and follow-up together. With time already in short supply in our schools, the time demands of this model make it difficult to use. Realistically, the Duet Model is only manageable when the specialist is co-teaching with one teacher, or two at the most. Teachers and administrators must be highly committed to co-planning and willing and able to set it as a top priority. Distractions and “take backs” must be minimized. For example, specialists report that they are occasionally pulled from co-taught instruction to cover for a teacher who is absent. This type of take back undermines the value of the Duet Model and is likely to lead to teacher hesitance to participate. Instead of minimizing the time Duet Model teachers have together, the school administrator must fiercely protect their collaboration.

GUIDING QUESTIONS WHEN CONSIDERING THE DUET MODEL

GUIDING QUESTIONS WHEN CONSIDERING THE DUET MODEL

- Do we have adequate common time to fully share the planning and assessment phases?

- Are we truly willing to view this class as “ours”?

- Do we both feel confident enough with the content knowledge to be equally responsible for the curriculum?

TO SUM UP

TO SUM UP

- In the Duet Model, both teachers fully share each phase of the instructional cycle. Their skills and experiences are smoothly integrated to provide a tightly integrated approach to teaching.

- Although the Duet Model is the best for students, it is the most time intensive and may not be realistic for specialists who are co-teaching with more than one or two teachers.