CHAPTER 11

Adapting Model

One of the most common models in use, the Adapting Model expects one of the two teachers, usually the specialist, to make necessary accommodations and modifications so that students will be successful. Some of these adaptations might be developed in advance, but many of them are made on the spot, making this a popular model with busy teachers.

At a Glance

It is third period at Washington High School. Mr. Parache’s and Mrs. Black’s co-taught geometry class is taking an end-of-the-unit test. As the principal pokes her head in the door, all students appear to be doing the same thing. Given that there are several students with IEPs, whose parents are ever-vigilant about accommodations, she asks Mrs. Black to stop by her office later in the day for a chat.

After the principal expresses her concern, Mrs. Black explains:

Mr. Parache e-mails me a copy of the test in advance. I make some format changes—things like extra space, larger font and clearer layout—and e-mail it back to him. He usually prints out copies of the same test for everyone … but sometimes just for the students who need the revised version. Then I audio record each test question so that students can listen to the test read aloud on iPods if they want to. The other thing we do is offer all the students in the class highlighter tape before the test. We encourage them to take a moment to look over the entire test before they begin and highlight the key directions. So when you poked your head in the door, we actually had three different types of accommodations in place—it just wasn’t obvious. These teenagers seem much more likely to use the accommodations if we can make them subtle.

This classroom example showcases the Adapting Model at its best. Adaptations are discussed, planned for, and implemented by the co-teachers in an unobtrusive manner. Students are provided with adaptations based on need rather than on label. Everyone in this class has the opportunity to benefit from strategic adaptations.

“Students are provided with adaptations based on need rather than on label.”

Before we delve further into this model, it will be helpful to clarify three terms that apply. Adaptation, accommodation, and modification are integral to our discussion, but are often confused and used interchangeably.

An adaptation is defined as the act or process of adjusting something to bring about greater success. Adaptations are used as a natural part of any teaching process and can be offered to students with and without special education labels.

An accommodation is defined as a change in materials or procedures that is provided to help a student fully access the general education curriculum or subject matter. An accommodation does not change the content of what is being taught nor the expectation that the student meet a performance standard applied for all students. Though this term is often used synonymously with adaptation, many educators associate it strictly with students on IEPs or 504 plans.

A modification is defined as a change to the general education curriculum or other material being taught that alters the standards or expectations for the student with disabilities. The student is no longer expected to be achieving at the grade level standard in a specific area of content. Modifications are usually reserved for students with more significant disabilities.

In the Adapting Model, all three processes can take place simultaneously. Teachers may agree on adaptations that are relevant to many students, with or without labels. Teachers may need to implement accommodations, based on agreements made in an IEP or 504 plan. And teachers may need to provide modifications for a student with more significant disabilities who is included in their class.

During the planning phase, co-teachers consider components of the lesson that might cause difficulty if not adapted. Common areas of concern include paper-and-pencil tests, heavy bouts of text reading, visually daunting worksheets, or socially demanding group projects. Adaptations may be discussed between the partners, or simply left as the responsibility of Teacher B to prepare.

Armed with adaptations, the instruction begins. An observer will notice Teacher A doing most of the leading, while Teacher B is providing adaptations and accommodations. Teacher A might be in the front of the room, lecturing or leading an activity, while Teacher B is wandering the room, stopping to help individual students in need of assistance. Teacher B might be seen carrying a tote, filled with strategic adaptation tools.

Strategic Adaptation Tools

- Sticky notes

- Sticky arrows

- Index cards

- Manipulatives

- Highlighters and highlighter tape

- Work masks

- Colored acetate strips

- Calculator

- Spell checker

- Correction fluid

See Appendix A

See Appendix A

Ideally, someone observing over time might also notice these roles flip-flopping. Teacher A benefits enormously from having the opportunity to work one-on-one with students who are struggling. The intimacy of these interactions provides the teacher insight into a specific student’s way of thinking. Is the student approaching the concept from a global or analytic perspective? Is it a specific step in the process that confuses the student, or the order of the steps? Is it a memory glitch or a comprehension problem? These opportunities also give the teacher a chance for reflection on the way he or she presented a concept—to consider if another way of teaching it might have led the student to easier acquisition.

“The intimacy of these interactions provides the teacher insight into a specific student’s way of thinking.”

Modifications are usually overseen by the specialist. These significant changes to curriculum might include finding off-grade-level texts, providing alternate assignments, using adaptive technology, or reducing homework. When modifications are provided in a co-taught class, students may voice questions or complaints. It is common to hear, “Why doesn’t he have to do as much work as we do?” It will serve partners well to discuss this potential complaint in advance and agree upon a response. Co-teachers might decide to explain to students that fair treatment does not mean equal treatment, and that every student’s individual needs will be considered.

During the assessment phase of teaching, Teacher B plays a vital role. As mentioned previously, adaptations to a formal assessment usually happen before it has been distributed. Borrowing from the concept of universal design, teachers should attempt to design a test that will not need to be adapted! Effective test design principles include those shown in Exhibit 11.1.

EXHIBIT 11.1: Test Design and Adaptation

Points to consider when designing matching items:

- Same number of items in each column

- Longer items in the left column, shorter in the right

- All items on one page

- Not more than ten items

Points to consider when designing sentence completion items:

- Use cues, such as blanks or first letters

- Use simple sentences

- Offer a word bank

Points to consider when designing true/false items

- Not more than ten items

- Avoid negative sentences

- Avoid double negatives in a sentence

- Use simple sentences

- Avoid tricky words such as “always”

Points to consider when designing essays and short answer items:

- Allow student to sketch a plan

- Specify the number of examples, points required

- Avoid complex sentences

- Offer choice of paper

Points to consider when designing multiple choice items:

- List items vertically

- No more than four choices

- Avoid combination answers, such as “all of the above”

- Use simple sentences

Points to consider when designing any test:

- Use Arial font

- Use 14 point

- Use a mixture of upper and lower case letters

Copyright © 2012 by Anne Beninghof

There are instances when a student may need specific accommodations that have been agreed to in his IEP. These might include having tests read aloud, using a scribe, or repeating test directions. In the past, these types of accommodations would have resulted in an instant assumption that the student would need to leave the room. In co-teaching, every attempt is made to keep the student in the room during testing. Why? Thanks to memory researchers, educators now know that learning environments are filled with invisible information that can aid student recall. For example, a student being tested on Newton’s first law of motion may form a mental picture of the balloon experiment done in class … if they are taking the test in the same classroom where the experiment occurred. Cues in the environment will lead the brain to fire up the neural pathways used in the original learning experience.

On the rare occasion when a student’s individual challenges require that he be removed to an alternative testing environment, the specialist will typically leave the room with him. This exodus should be as unobtrusive as possible to minimize embarrassment for the student. At the secondary level, teachers often arrange in advance for the student to go directly to the alternative space, rather than having to exit class after it has begun.

Roles and Responsibilities

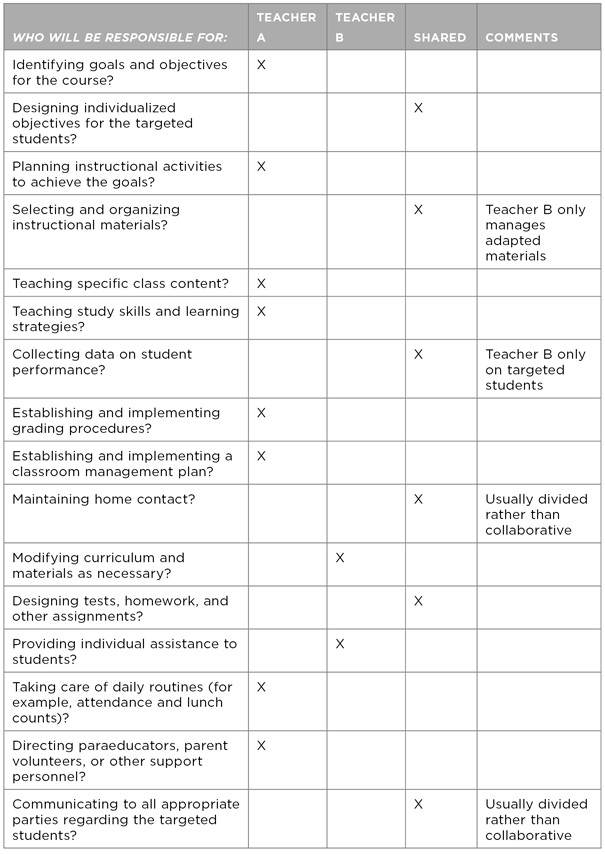

The role of Teacher B is very limited in the Adapting Model, as detailed in Table 11.1, causing the benefits of this co-teaching model to also be very limited. While there are some schools that utilize just this model and claim to be co-teaching, they are doing so in a very minimalist fashion. Teacher B is operating more like a paraeducator than a highly trained professional, and even in that role is underutilized. However, if the co-teachers blend this model with several others, then the specialist is truly a partner in the teaching process and all students benefit.

TABLE 11.1: Collaborative Teaching Responsibilities Checklist—Adapting

Pros and Cons

Three small but distinct advantages accompany the Adapting Model. First, this model is time efficient, if used as a stand-alone model. The co-teachers need very little common planning time. Instead, the general educator can provide a copy of the lesson plan by e-mail or mailbox, and the specialist can choose appropriate adaptations. The specialist can arrive in the room armed with her toolbox and wander around the room to support specific students. Of course, this lack of co-planning has disadvantages, as will be discussed below.

The second advantage is that it encourages one of the two teachers to focus specifically on individualizing instruction for targeted students. Usually, targeted students have struggled with whole-group, one-size-fits-all instruction and have demonstrated a clear need for something different. In the Adapting Model, Teacher B has the mandate to present these students with adaptations designed to meet their unique needs.

Closely linked to these first two benefits, the third advantage to the Adapting Model is that it delineates clear responsibility to one of the partners for ensuring that IEP or 504 Plan commitments are kept. In the high-energy, co-taught classroom, it is easy to lose sight of specific legal agreements. Collaborative partners are busy with co-managing many facets of the instructional process, and specific accommodations can be overlooked. The Adapting Model strives to avoid this problem by not only clarifying responsibility for these, but also highlighting this responsibility.

Two major concerns jump immediately to mind when the Adapting Model is used as a stand-alone. First, as alluded to earlier, the lack of co-planning can lead to weak interventions. If Teacher B doesn’t fully understand the nature of the lesson, adaptations may miss the mark or end up being trivial. The adaptations seem like a band-aid, rather than a healthy, preventative measure. It is just not possible for Teacher B to provide high-quality adaptations if she is not involved in ongoing conversation with Teacher A.

The second major concern is that Teacher B is underutilized in the Adapting Model. Though her skills in providing accommodations and modifications will be applied to individual students, any other teaching skills she has will go untapped. This is especially true in the case of a highly trained professional specialist. This model puts her in a role that could easily be assumed by someone with fewer qualifications (and lower on the pay scale.)

With these concerns in mind, the question arises “Should we use the Adapting Model at all?” The answer is “Yes!”—in conjunction with other models to form a more comprehensive approach to collaboration.

GUIDING QUESTIONS WHEN CONSIDERING THE ADAPTING MODEL

GUIDING QUESTIONS WHEN CONSIDERING THE ADAPTING MODEL

- How can we communicate thoroughly enough about the lesson plan to ensure that the adaptations are relevant and effective?

- How will we respond to student complaints about different or reduced assignments?

- Are there obvious times when Teacher A and B roles can be swapped?

- Will we blend this model with other models to ensure that Teacher B’s expertise is fully utilized?

TO SUM UP

TO SUM UP

- In the most common approach to the Adapting Model, the specialist provides small changes to instruction and assessment that make learning more accessible for targeted students. This can be planned for in advance or developed on the spot. Less common, but still valuable, is when the classroom teacher offers the adaptations to students who need them.

- Although this model is an important asset to a co-taught class, it is best when paired with other models so that the skills of the specialist are more fully utilized.