Chapter 4

THE WEB, THE TREE, AND THE STRING

UNDERSTANDING SYNTAX CAN HELP A WRITER AVOID UNGRAMMATICAL, CONVOLUTED, AND MISLEADING PROSE

Kids aren’t taught to diagram sentences anymore.” Together with “The Internet is ruining the language” and “People write gibberish on purpose,” this is the explanation I hear most often for the prevalence of bad writing today.

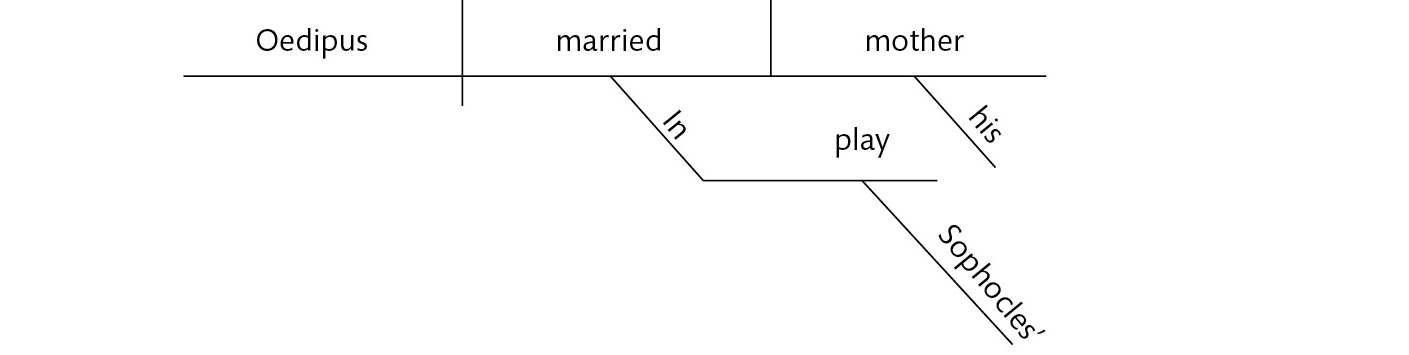

The plaint about the lost art of diagramming sentences refers to a notation that was invented by Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg in 1877 and taught in American schools until the 1960s, when it fell victim to the revolt among educators against all things formal.1 In this system, the words of a sentence are placed along a kind of subway map in which intersections of various shapes (perpendicular, slanted, branching) stand for grammatical relations such as subject-predicate and modifier-head. Here, for instance, is how you would diagram the sentence In Sophocles’ play, Oedipus married his mother:

The Reed-Kellogg notation was innovative in its day, but I for one don’t miss it. It’s just one way to display syntax on a page, and not a particularly good one, with user-unfriendly features such as scrambled word order and arbitrary graphical conventions. But I agree with the main idea behind the nostalgia: literate people should know how to think about grammar.

People already know how to use grammar, of course; they’ve been doing it since they were two. But the unconscious mastery of language that is our birthright as humans is not enough to allow us to write good sentences. Our tacit sense of which words go together can break down when a sentence gets complicated, and our fingers can produce an error we would never accept if we had enough time and memory to take in the sentence at a glance. Learning how to bring the units of language into consciousness can allow a writer to reason his way to a grammatically consistent sentence when his intuitions fail him, and to diagnose the problem when he knows something is wrong with the sentence but can’t put his finger on what it is.

Knowing a bit of grammar also gives a writer an entrée into the world of letters. Just as cooks, musicians, and ballplayers have to master some lingo to be able to share their tips and learn from others, so writers can benefit by knowing the names of the materials they work with and how they do their jobs. Literary analysis, poetics, rhetoric, criticism, logic, linguistics, cognitive science, and practical advice on style (including the other chapters in this book) need to refer to things like predicates and subordinate clauses, and knowing what these terms mean will allow a writer to take advantage of the hard-won knowledge of others.

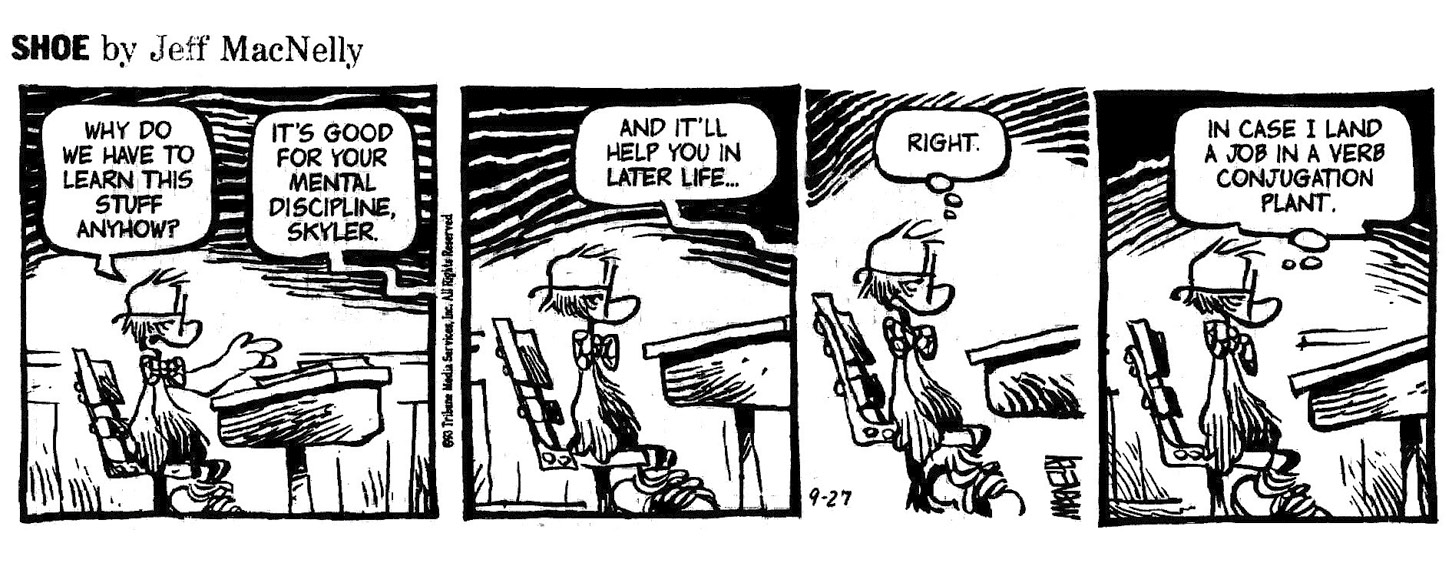

Best of all, grammar is a fascinating subject in its own right, at least when it is properly explained. To many people the very word conjures up memories of choking on chalk dust and cowering in fear of a thwack on the knuckles from a spinster schoolteacher. (Theodore Bernstein, the author of several style manuals, refers to the archetype as Miss Thistlebottom; the writer Kitty Burns Florey, who wrote a history of diagramming sentences, calls her Sister Bernadette.) But grammar should not be thought of as an ordeal of jargon and drudgery, as Skyler does in this Shoe cartoon:

It should be thought of instead as one of the extraordinary adaptations in the living world: our species’ solution to the problem of getting complicated thoughts from one head into another. Thinking of grammar as the original sharing app makes it much more interesting and much more useful. By understanding how the various features of grammar are designed to make sharing possible, we can put them to use in writing more clearly, correctly, and gracefully.

• • •

The three nouns in the chapter title refer to the three things that grammar brings together: the web of ideas in our head, the string of words that comes out of our mouth or fingers, and the tree of syntax that converts the first into the second.

Let’s begin with the web. As you wordlessly daydream, your thoughts drift from idea to idea: visual images, odd observations, snatches of melody, fun facts, old grudges, pleasant fantasies, memorable moments. Long before the invention of the World Wide Web, cognitive scientists modeled human memory as a network of nodes. Each node represents a concept, and each is linked to other nodes for words, images, and other concepts.2 Here is a fragment of this vast, mind-wide web, spotlighting your knowledge of the tragic story brought to life by Sophocles:

Though I had to place each node somewhere on the page, their positions don’t matter, and they don’t have any ordering. All that matters is how they’re connected. A train of thought might start with any of these concepts, triggered by the mention of a word, by a pulse of activation on an incoming link originating from some other concept far away in the network, or by whatever random neural firings cause an idea to pop into mind unbidden. From there your mind can surf in any direction along any link to any of the other concepts.

Now, what happens if you wanted to share some of those thoughts? One can imagine a race of advanced space aliens who could compress a portion of this network into a zipped file of bits and hum it to each other like two dial-up modems. But that’s not the way it’s done in Homo sapiens. We have learned to associate each thought with a little stretch of sound called a word, and can cause each other to think that thought by uttering the sound. But of course we need to do more than just blurt out individual words. If you were unfamiliar with the story of Oedipus Rex and I simply said, “Sophocles play story kill Laius wife Jocasta wed Oedipus father mother,” you wouldn’t guess what happened in a million years. In addition to reciting names for the concepts, we utter them in an order that signals the logical relationships among them (doer, done-to, is a, and so on): Oedipus killed Laius, who was his father. Oedipus married Jocasta, who was his mother. The code that translates a web of conceptual relations in our heads into an early-to-late order in our mouths, or into a left-to-right order on the page, is called syntax.3 The rules of syntax, together with the rules of word formation (the ones that turn kill into kills, killed, and killing), make up the grammar of English. Different languages have different grammars, but they all convey conceptual relationships by modifying and arranging words.4

It’s not easy to design a code that can extrude a tangled spaghetti of concepts into a linear string of words. If an event involves several characters involved in several relationships, there needs to be a way to keep track of who did what to whom. Killed Oedipus married Laius Jocasta, for example, doesn’t make it clear whether Oedipus killed Laius and married Jocasta, Jocasta killed Oedipus and married Laius, Oedipus killed Jocasta and married Laius, and so on. Syntax solves this problem by having adjacent strings of words stand for related sets of concepts, and by inserting one string inside another to stand for concepts that are parts of bigger concepts.

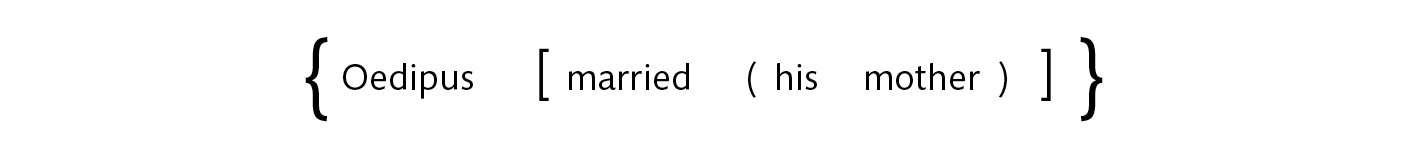

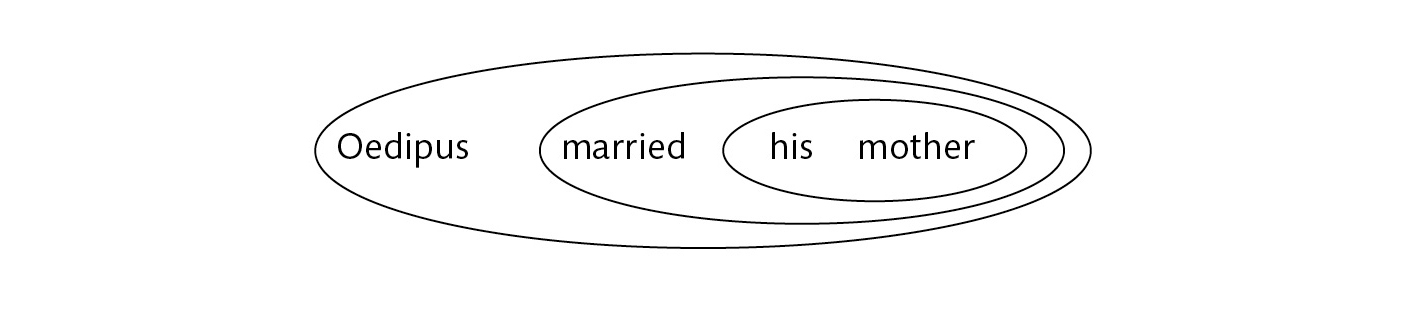

To understand how syntax works, it helps to visualize the ordering of strings-within-strings by drawing them at the ends of the branches of an upside-down tree.

I’ll explain the details soon, but for now it’s enough to notice that the words at the bottom (like mother) are grouped into phrases (like his mother), which are grouped into larger phrases (like married his mother), which are grouped into a clause (a simple sentence like Oedipus married his mother), which in turn may be inserted into a bigger clause (the whole sentence).

Syntax, then, is an app that uses a tree of phrases to translate a web of thoughts into a string of words. Upon hearing or reading the string of words, the perceiver can work backwards, fitting them into a tree and recovering the links between the associated concepts. In this case a hearer can deduce that Sophocles wrote a play in which Oedipus married his mother, rather than that Oedipus wrote a play in which Sophocles married his mother, or just that the speaker is saying something about a bunch of Greeks.

The tree, of course, is only a metaphor. What it captures is that adjacent words are grouped into phrases, that the phrases are embedded inside larger phrases, and that the arrangement of words and phrases may be used to recover the relationships among the characters in the speaker’s mind. A tree is simply an easy way to display that design on a page. The design could just as accurately be shown with a series of braces and brackets, or with a Venn diagram:

Regardless of the notation, appreciating the engineering design behind a sentence—a linear ordering of phrases which conveys a gnarly network of ideas—is the key to understanding what you are trying to accomplish when you compose a sentence. And that, in turn, can help you understand the menu of choices you face and the things that are most likely to go wrong.

The reason that the task is so challenging is that the main resource that English syntax makes available to writers—left-to-right ordering on a page—has to do two things at once. It’s the code that the language uses to convey who did what to whom. But it also determines the sequence of early-to-late processing in the reader’s mind. The human mind can do only a few things at a time, and the order in which information comes in affects how that information is handled. As we’ll see, a writer must constantly reconcile the two sides of word order: a code for information, and a sequence of mental events.

• • •

Let’s begin with a closer look at the code of syntax itself, using the tree for the Oedipus sentence as an example.5 Working upward from the words at the bottom, we see that every word is labeled with a grammatical category. These are the “parts of speech” that should be familiar even to people who were educated after the 1960s:

|

Nouns (including pronouns) |

man, play, Sophocles, she, my |

|

Verbs |

marry, write, think, see, imply |

|

Prepositions |

in, around, underneath, before, until |

|

Adjectives |

big, red, wonderful, interesting, demented |

|

Adverbs |

merrily, frankly, impressively, very, almost |

|

Articles and other determinatives |

the, a, some, this, that, many, one, two, three |

|

Coordinators |

and, or, nor, but, yet, so |

|

Subordinators |

that, whether, if, to |

Each word is slotted into a place in the tree according to its category, because the rules of syntax don’t specify the order of words but rather the order of categories. Once you have learned that in English the article comes before the noun, you don’t have to relearn that order every time you acquire a new noun, such as hashtag, app, or MOOC. If you’ve seen one noun, you’ve pretty much seen them all. There are, to be sure, subcategories of the noun category like proper nouns, common nouns, mass nouns, and pronouns, which indulge in some additional pickiness about where they appear, but the principle is the same: words within a subcategory are interchangeable, so that if you know where the subcategory may appear, you know where every word in that subcategory may appear.

Let’s zoom in on one of the words, married. Together with its grammatical category, verb, we see a label in parentheses for its grammatical function, in this case, head. A grammatical function identifies not what a word is in the language but what it does in that particular sentence: how it combines with the other words to determine the sentence’s meaning.

The “head” of a phrase is the little nugget which stands for the whole phrase. It determines the core of the phrase’s meaning: in this case married his mother is a particular instance of marrying. It also determines the grammatical category of the phrase: in this case it is a verb phrase, a phrase built around a verb. A verb phrase is a string of words of any length which fills a particular slot in a tree. No matter how much stuff is packed into the verb phrase—married his mother; married his mother on Tuesday; married his mother on Tuesday over the objections of his girlfriend—it can be inserted into the same position in the sentence as the phrase consisting solely of the verb married. This is true of the other kinds of phrases as well: the noun phrase the king of Thebes is built around the head noun king, it refers to an example of a king, and it can go wherever the simpler phrase the king can go.

The extra stuff that plumps out a phrase may include additional grammatical functions which distinguish the various roles in the story identified by the head. In the case of marrying, the dramatis personae include the person being married and the person doing the marrying. (Though marrying is really a symmetrical relationship—if Jack married Jill, then Jill married Jack—let’s assume for the sake of the example that the male takes the initiative in marrying the female.) The person being married in this sentence is, tragically, the referent of his mother, and she is identified as the one being married because the phrase has the grammatical function “object,” which in English is the noun phrase following the verb. The person doing the marrying, referred to by the one-word phrase Oedipus, has the function “subject.” Subjects are special: all verbs have one, and it sits outside the verb phrase, occupying one of the two major branches of the clause, the other being the predicate. Still other grammatical functions can be put to work in identifying other roles. In Jocasta handed the baby to the servant, the phrase the servant is an oblique object, that is, the object of a preposition. In Oedipus thought that Polybus was his father, the clause that Polybus was his father is a complement of the verb thought.

Languages also have grammatical functions whose job is not to distinguish the cast of characters but to pipe up with other kinds of information. Modifiers can add comments on the time, place, manner, or quality of a thing or an action. In this sentence we have the phrase In Sophocles’ play as a modifier of the clause Oedipus married his mother. Other examples of modifiers include the underlined words in the phrases walks on four legs, swollen feet, met him on the road to Thebes, and the shepherd whom Oedipus had sent for.

We also find that the nouns play and mother are preceded by the words Sophocles’ and his, which have the function “determiner.” A determiner answers the question “Which one?” or “How many?” Here the determiner role is filled by what is traditionally called a possessive noun (though it is really a noun marked for genitive case, as I will explain). Other common determiners include articles, as in the cat and this boy; quantifiers, as in some nights and all people; and numbers, as in sixteen tons.

If you are over sixty or went to private school, you may have noticed that this syntactic machinery differs in certain ways from what you remember from Miss Thistlebottom’s classroom. Modern grammatical theories (like the one in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, which I use in this book) distinguish grammatical categories like noun and verb from grammatical functions like subject, object, head, and modifier. And they distinguish both of these from semantic categories and roles like action, physical object, possessor, doer, and done-to, which refer to what the referents of the words are doing in the world. Traditional grammars tend to run the three concepts together.

As a child I was taught, for example, that the words soap in soap flakes and that in that boy were adjectives, because they modify nouns. But this confuses the grammatical category “adjective” with the grammatical function “modifier.” There’s no need to wave a magic wand over the noun soap and transmute it into an adjective just because of what it’s doing in this phrase. It’s simpler to say that sometimes a noun can modify another noun. In the case of that in that boy, Miss Thistlebottom got the function wrong, too: it’s determiner, not modifier. How do we know? Because determiners and modifiers are not interchangeable. You can say Look at the boy or Look at that boy (determiners), but not Look at tall boy (a modifier). You can say Look at the tall boy (determiner + modifier), but not Look at the that boy (determiner + determiner).

I was also taught that a “noun” is a word for a person, place, or thing, which confuses a grammatical category with a semantic category. The comedian Jon Stewart was confused, too, because on his show he criticized George W. Bush’s “War on Terror” by protesting, “Terror isn’t even a noun!”6 What he meant was that terror is not a concrete entity, in particular a group of people organized into an enemy force. Terror, of course, is a noun, together with thousands of other words that don’t refer to people, places, or things, including the nouns word, category, show, war, and noun, to take just some examples from the past few sentences. Though nouns are often the names for people, places, and things, the noun category can only be defined by the role it plays in a family of rules. Just as a “rook” in chess is defined not as the piece that looks like a little tower but as the piece that is allowed to move in certain ways in the game of chess, a grammatical category such as “noun” is defined by the moves it is allowed to make in the game of grammar. These moves include the ability to appear after a determiner (the king), the requirement to have an oblique rather than a direct object (the king of Thebes, not the king Thebes), and the ability to be marked for plural number (kings) and genitive case (king’s). By these tests, terror is certainly a noun: the terror, terror of being trapped, the terror’s lasting impact.

Now we can see why the word Sophocles’ shows up in the tree with the category “noun” and the function “determiner” rather than “adjective.” The word belongs to the noun category, just as it always has; Sophocles did not suddenly turn into an adjective just because it is parked in front of another noun. And its function is determiner because it acts in the same way as the words the and that and differently from a clear-cut modifier like famous: you can say In Sophocles’ play or In the play, but not In famous play.

At this point you may be wondering: What’s with “genitive”? Isn’t that just what we were taught is the possessive? Well, “possessive” is a semantic category, and the case indicated by the suffix ’s and by pronouns like his and my needn’t have anything to do with possession. When you think about it, there is no common thread of ownership, or any other meaning, across the phrases Sophocles’ play, Sophocles’ nose, Sophocles’ toga, Sophocles’ mother, Sophocles’ hometown, Sophocles’ era, and Sophocles’ death. All that the Sophocles’s have in common is that they fill the determiner slot in the tree and help you determine which play, which nose, and so on, the speaker had in mind.

More generally, it’s essential to keep an open mind about how to diagram a sentence rather than assuming that everything you need to know about grammar was figured out before you were born. Categories, functions, and meanings have to be ascertained empirically, by running little experiments such as substituting a phrase whose category you don’t know for one you do know and seeing whether the sentence still works. Based on these mini-experiments, modern grammarians have sorted words into grammatical categories that sometimes differ from the traditional pigeonholes.

There is a reason why the list on page 84, for example, doesn’t have the traditional category called “conjunction,” with the subtypes “coordinating conjunction” (words like and and or) and “subordinating conjunction” (words like that and if). It turns out that coordinators and subordinators have nothing in common, and there is no category called “conjunction” that includes them both. For that matter, many of the words that were traditionally called subordinating conjunctions, like before and after, are actually prepositions.7 The after in after the love has gone, for example, is just the after which appears in after the dance, which everyone agrees is a preposition. It was just a failure of the traditional grammarians to distinguish categories from functions that blinded them to the realization that a preposition could take a clause, not just a noun phrase, as its object.

Why does any of this matter? Though you needn’t literally diagram sentences or master a lot of jargon to write well, the rest of this chapter will show you a number of ways in which a bit of syntactic awareness can help you out. First, it can help you avoid some obvious grammatical errors, those that are errors according to your own lights. Second, when an editor or a grammatical stickler claims to find an error in a sentence you wrote, but you don’t see anything wrong with it, you can at least understand the rule in question well enough to decide for yourself whether to follow it. As we shall see in chapter 6, many spurious rules, including some that have made national headlines, are the result of bungled analyses of grammatical categories like adjective, subordinator, and preposition. Finally, an awareness of syntax can help you avoid ambiguous, confusing, and convoluted sentences. All of this awareness depends on a basic grasp of what grammatical categories are, how they differ from functions and meanings, and how they fit into trees.

• • •

Trees are what give language its power to communicate the links between ideas rather than just dumping the ideas in the reader’s lap. But they come at a cost, which is the extra load they impose on memory. It takes cognitive effort to build and maintain all those invisible branches, and it’s easy for reader and writer alike to backslide into treating a sentence as just one damn word after another.

Let’s start with the writer. When weariness sets in, a writer’s ability to behold an entire branch of the tree can deteriorate. His field of vision shrinks to a peephole, and he sees just a few adjacent words in the string at a time. Most grammatical rules are defined over trees, not strings, so this momentary tree-blindness can lead to pesky errors.

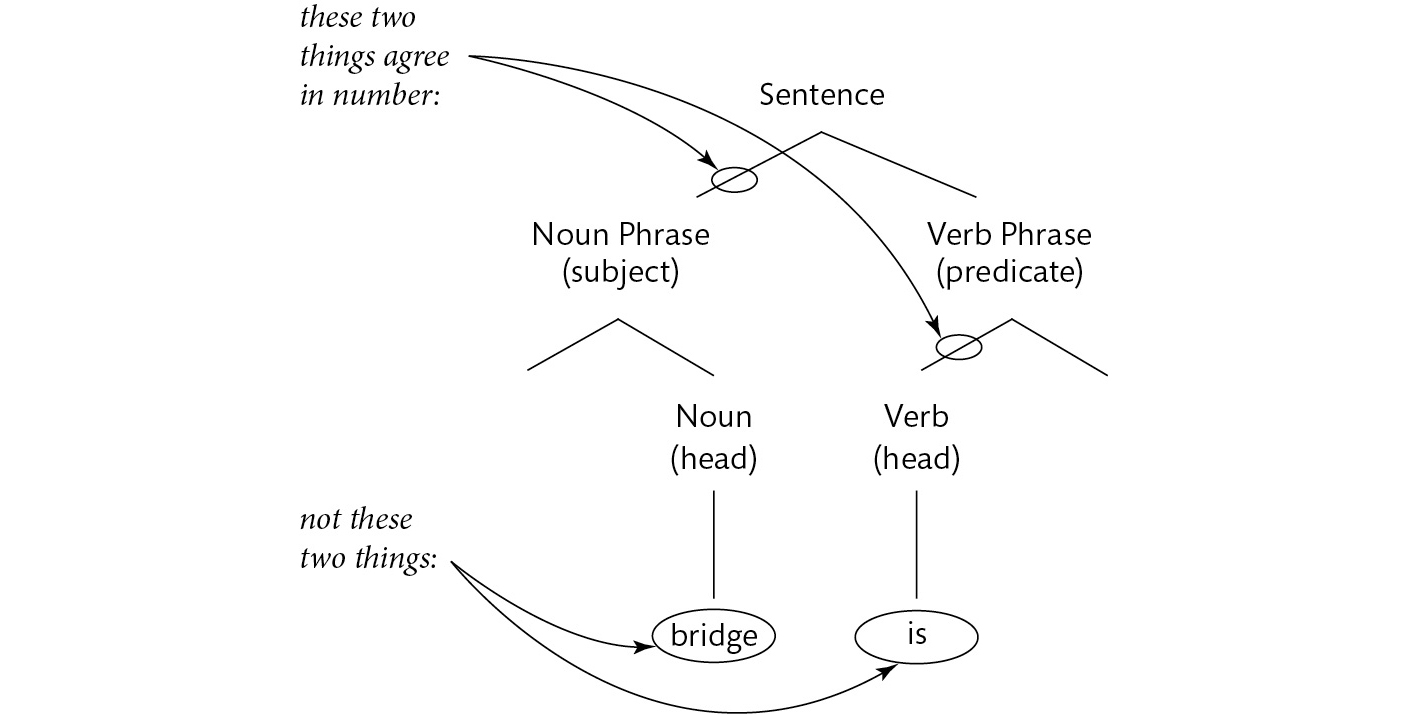

Take agreement between the subject and the verb: we say The bridge is crowded, but The bridges are crowded. It’s not a hard rule to follow. Children pretty much master it by the age of three, and errors such as I can has cheezburger and I are serious cat are so obvious that a popular Internet meme (LOLcats) facetiously attributes them to cats. But the “subject” and “verb” that have to agree are defined by branches in the tree, not words in the string:

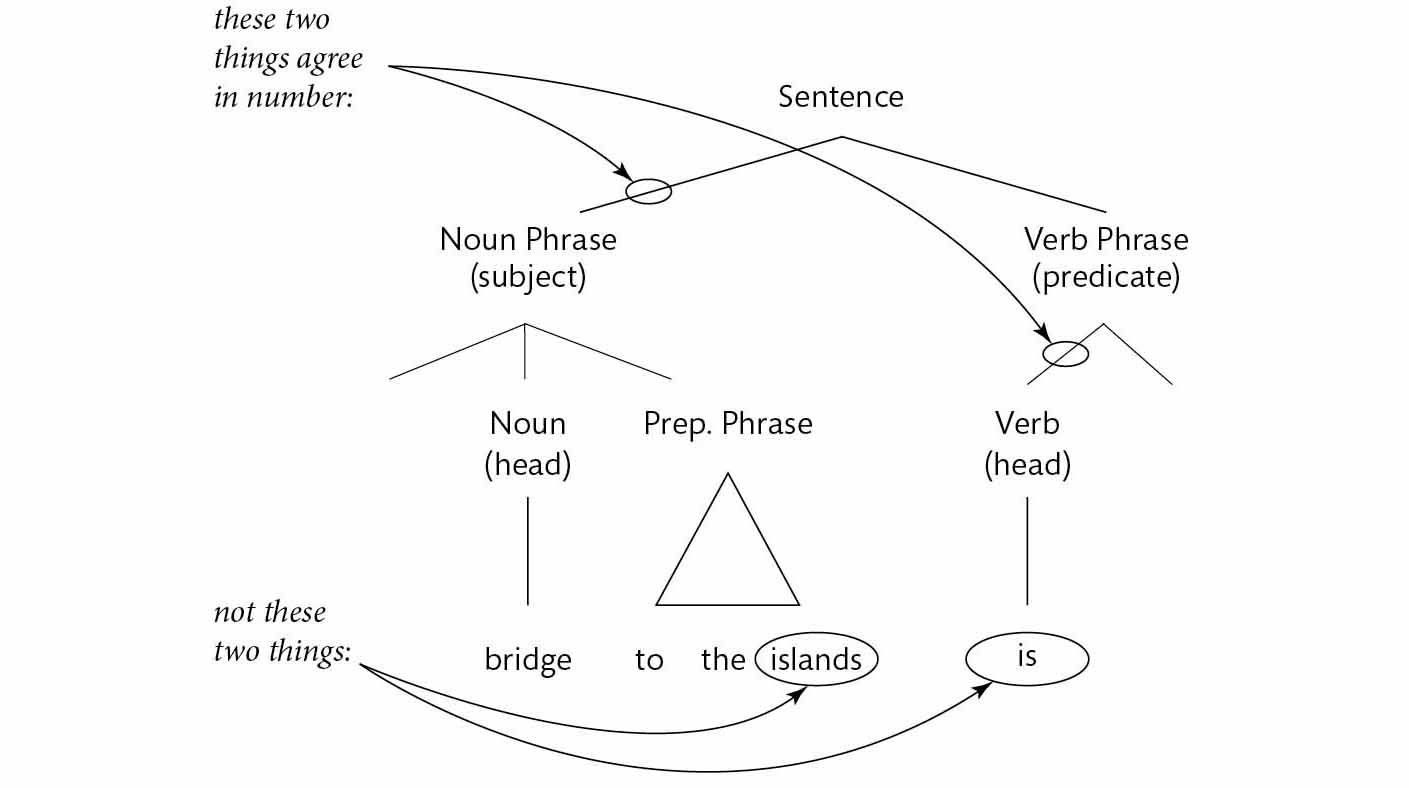

You might be thinking, What difference does it make? Doesn’t the sentence come out the same either way? The answer is that it doesn’t. If you fatten up the subject by stuffing some words at the end, as in the diagram below, so that bridge no longer comes right before the verb, then agreement—defined over the tree—is unaffected. We still say The bridge to the islands is crowded, not The bridge to the islands are crowded.

But thanks to tree-blindness, it’s common to slip up and type The bridge to the islands are crowded. If you haven’t been keeping the tree suspended in memory, the word islands, which is ringing in your mind’s ear just before you type the verb, will contaminate the number you give the verb. Here are a few other agreement errors that have appeared in print:8

The readiness of our conventional forces are at an all-time low.

At this stage, the accuracy of the quotes have not been disputed.

The popularity of “Family Guy” DVDs were partly credited with the 2005 revival of the once-canceled Fox animated comedy.

The impact of the cuts have not hit yet.

The maneuvering in markets for oil, wheat, cotton, coffee and more have brought billions in profits to investment banks.

They’re easy to miss. As I am writing this chapter, every few pages I see the green wiggly line of Microsoft Word’s grammar checker, and usually it flags an agreement error that slipped under my tree-spotting radar. But even the best software isn’t smart enough to assign trees reliably, so writers cannot offload the task of minding the tree onto their word processors. In the list of agreement errors above, for example, the last two sentences appear on my screen free of incriminating squiggles.

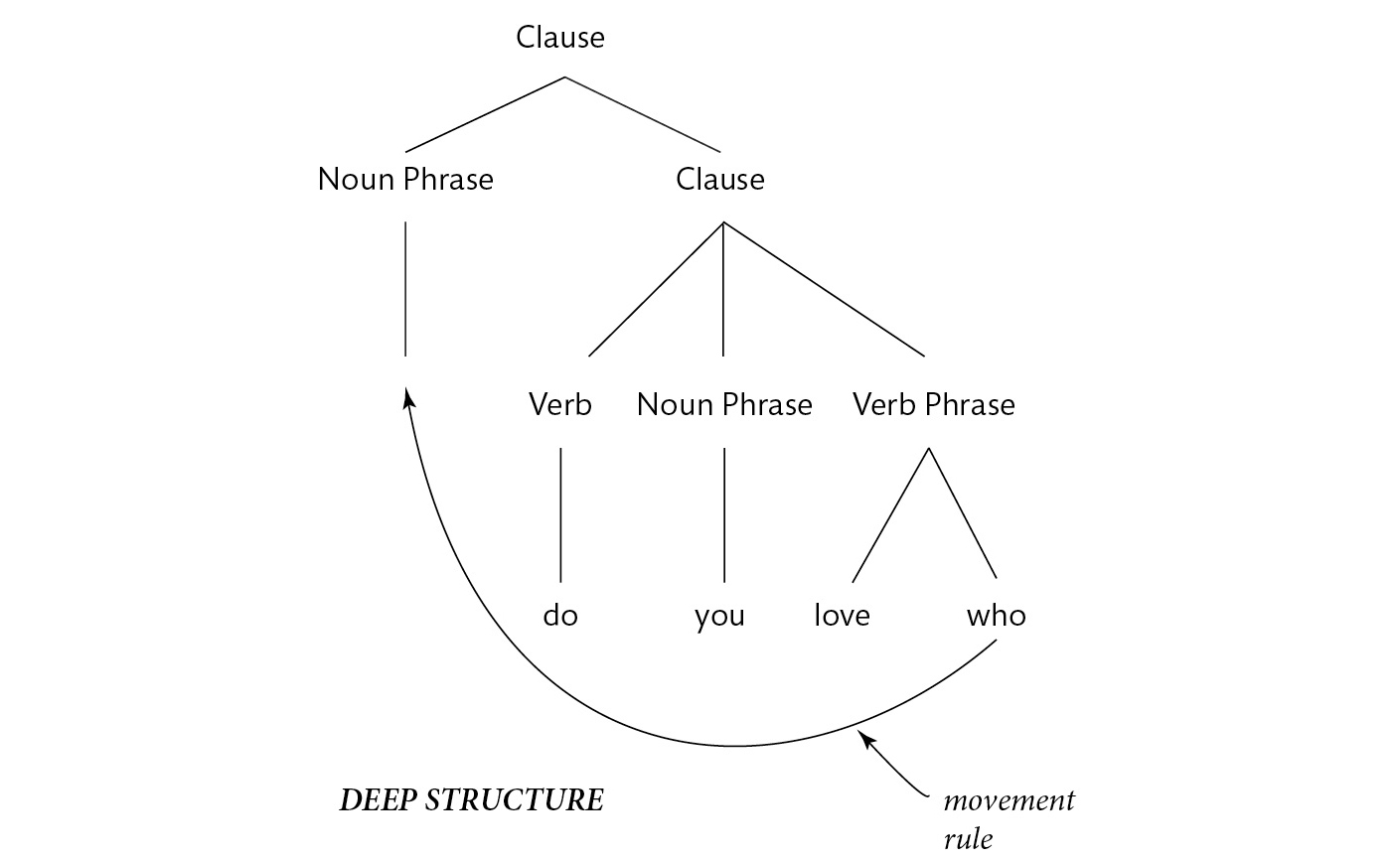

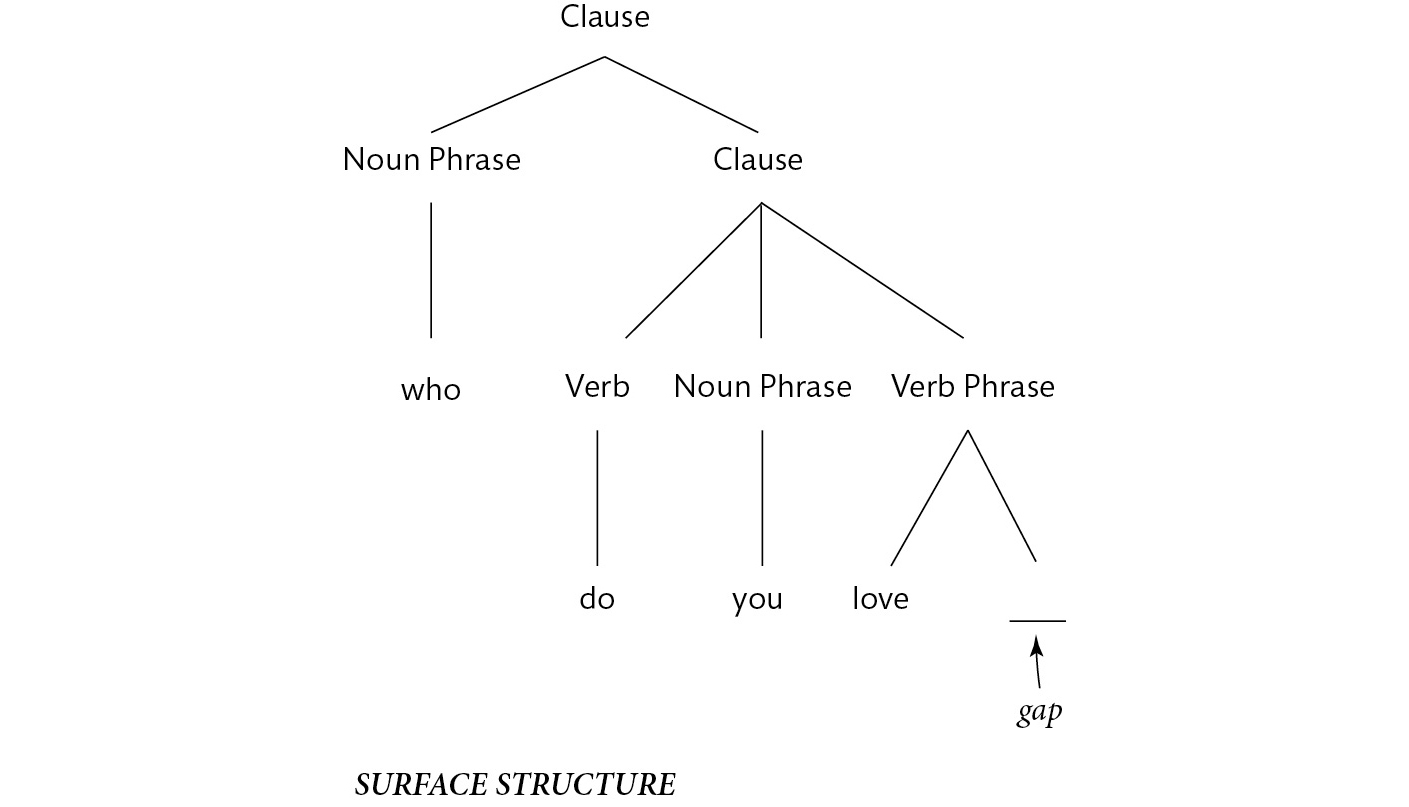

Wedging an extra phrase into a tree is just one of the ways in which a subject can be separated from its verb. Another is the grammatical process that inspired the linguist Noam Chomsky to propose his famous theory in which a sentence’s underlying tree—its deep structure—is transformed by a rule that moves a phrase into a new position, yielding a slightly altered tree called a surface structure.9 This process is responsible, for example, for questions containing wh-words, such as Who do you love? and Which way did he go? (Don’t get hung up on the choice between who and whom just yet—we’ll get to that later.) In the deep structure, the wh-word appears in the position you’d expect for an ordinary sentence, in this case after the verb love, as in I love Lucy. The movement rule then brings it to the front of the sentence, leaving a gap (the underscored blank) in the surface structure. (From here on, I’ll keep the trees uncluttered by omitting unnecessary labels and branches.)

We understand the question by mentally filling the gap with the phrase that was moved out of it. Who do you love __? means “For which person do you love that person?”

The movement rule also generates a common construction called a relative clause, as in the spy who __ came in from the cold and the woman I love __. A relative clause is a clause with a gap in it (I love __) which modifies a noun phrase (the woman). The position of the gap indicates the role that the modified phrase played in the deep structure; to understand the relative clause, we mentally fill it back in. The first example means “the spy such that the spy came in from the cold.” The second means “the woman such that I love the woman.”

The long distance between a filler and a gap can be hazardous to writer and reader alike. When we’re reading and we come across a filler (like who or the woman), we have to hold it in memory while we handle all the material that subsequently pours in, until we locate the gap that it is meant to fill.10 Often that is too much for our thimble-sized memories to handle, and we get distracted by the intervening words:

The impact, which theories of economics predict ____ are bound to be felt sooner or later, could be enormous.

Did you even notice the error? Once you plug the filler the impact into the gap after predict, yielding the impact are bound to be felt, you see that the verb must be is, not are; the error is as clear as I are serious cat. But the load on memory can allow the error to slip by.

Agreement is one of several ways in which one branch of a tree can be demanding about what goes into another branch. This demandingness is called government, and it can also be seen in the way that verbs and adjectives are picky about their complements. We make plans but we do research; it would sound odd to say that we do plans or make research. Bad people oppress their victims (an object), rather than oppressing against their victims (an oblique object); at the same time, they may discriminate against their victims, but not discriminate them. Something can be identical to something else, but must coincide with it; the words identical and coincide demand different prepositions. When phrases are rearranged or separated, a writer can lose track of what requires what else, and end up with an annoying error:

Among the reasons for his optimism about SARS is the successful research that Dr. Brian Murphy and other scientists have made at the National Institutes of Health.11

People who are discriminated based on their race are often resentful of their government and join rebel groups.

The religious holidays to which the exams coincide are observed by many of our students.

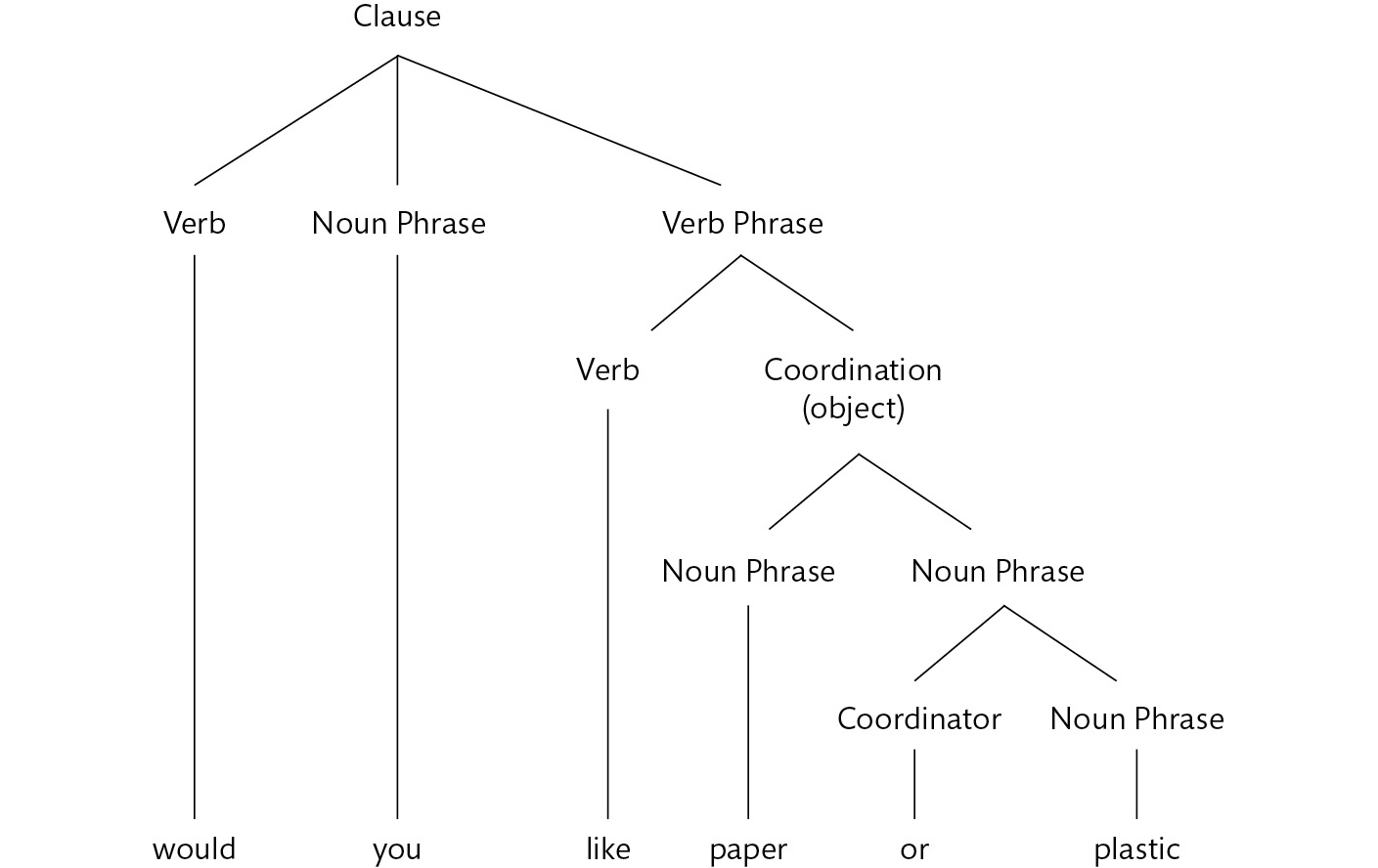

One of the commonest forms of tree-blindness consists of a failure to look carefully at each branch of a coordination. A coordination, traditionally called a conjunction, is a phrase composed of two or more phrases which are linked by a coordinator (the land of the free and the home of the brave; paper or plastic) or strung together with commas (Are you tired, run down, listless?).

Each of the phrases in a coordination has to work in that position on its own, as if the other phrases weren’t there, and they must have the same function (object, modifier, and so on). Would you like paper or plastic? is a fine sentence because you can say Would you like paper? with paper as the object of like, and you can also say Would you like plastic? with plastic as the object of like. Would you like paper or conveniently? is ungrammatical, because conveniently is a modifier, and it’s a modifier that doesn’t work with like; you would never say Would you like conveniently? No one is tempted to make that error, because like and conveniently are cheek by jowl, which makes the clash obvious. And no one is tempted to say Would you like paper or conveniently? because they can mentally block out the intervening paper and or, whereupon the clash between like and conveniently becomes just as blatant. That’s the basis of the gag title of the comedian Stephen Colbert’s 2007 bestseller, intended to flaunt the illiteracy of his on-screen character: I Am America (And So Can You!).

When a sentence gets complicated, though, even a literate writer can lose track of how each branch in a coordination harmonizes with the rest of the tree. The writer of the slogan We get the job done, not make excuses presumably did not anticipate how customers would wince at the bad coordination. While the phrase get the job done is a present-tense predicate that goes with the subject we, the phrase not make excuses is non-tensed and can’t go with the subject on its own (We not make excuses); it can only be a complement of an auxiliary verb like do or will. To repair the slogan, one could coordinate two complete clauses (We get the job done; we don’t make excuses), or one could coordinate two complements of a single verb (We will get the job done, not make excuses).

A more subtle kind of off-kilter coordination creeps into writing so often that it is a regular source of mea culpas in newspaper columns in which an editor apologizes to readers for the mistakes that slipped into the paper the week before. Here are a few caught by the New York Times editor Philip Corbett for his “After Deadline” feature, together with repaired versions on the right (I’ve underlined and bracketed the words that were originally miscoordinated):12

|

He said that surgeries and therapy had helped him not only [to recover from his fall], but [had also freed him of the debilitating back pain]. |

He said that surgeries and therapy had not only [helped him to recover from his fall], but also [freed him of the debilitating back pain]. |

|

With Mr. Ruto’s appearance before the court, a process began that could influence not only [the future of Kenya] but also [of the much-criticized tribunal]. |

With Mr. Ruto’s appearance before the court, a process began that could influence the future not only [of Kenya] but also [of the much-criticized tribunal]. |

|

Ms. Popova, who died at 91 on July 8 in Moscow, was inspired both [by patriotism] and [a desire for revenge]. |

Ms. Popova was inspired by both [patriotism] and [a desire for revenge]. Or Ms. Popova was inspired both [by patriotism] and [by a desire for revenge]. |

In these examples, the coordinates come in matched pairs, with a quantifier (both, either, neither, not only) marking the first coordinate, and a coordinator (and, or, nor, but also) marking the second. The markers, underlined in the examples, pair off this way:

not only . . . but also . . .

both . . . and . . .

either . . . or . . .

neither . . . nor . . .

These coordinations are graceful only when the phrases coming after each marker—the ones enclosed in brackets above—are parallel. Because quantifiers like both and either have a disconcerting habit of floating around the sentence, the phrases that come after them may end up nonparallel, and that grates on the ear. In the sentence about surgeries, for example, we have to recover in the first coordinate (an infinitive) clashing with freed him in the second (a participle). The easiest way to repair an unbalanced coordination is to zero in on the second coordinate and then force the first coordinate to match it by sliding its quantifier into a more suitable spot. In this case, we want the first coordinate to be headed by a participle, so that it matches freed him in the second. The solution is to pull not only two slots leftward, giving us the pleasing symmetry between helped him and freed him. (Since the first had presides over the entire coordination, the second one is now unnecessary.) In the next example, we have a direct object in the first coordinate (the future of Kenya) jangling with an oblique object (of the tribunal) in the second; by pushing not only rightward, we get the neatly twinned phrases of Kenya and of the tribunal. The final example, also marred by mismatched objects (by patriotism and a desire for revenge), can be repaired in either of two ways: by nudging the both rightward (yielding patriotism and a desire for revenge), or by supplying the second coordinate with a by to match the first one (by patriotism and by a desire for revenge).

Yet another hazard of tree-blindness is the assignment of case. Case refers to the adornment of a noun phrase with a marker that advertises its typical grammatical function, such as nominative case for subjects, genitive case for determiners (the function mistakenly called “possessor” in traditional grammars), and accusative case for objects, objects of prepositions, and everything else. In English, case applies mainly to pronouns. When Cookie Monster says Me want cookie and Tarzan says Me Tarzan, you Jane, they are using an accusative pronoun for a subject; everyone else uses the nominative pronoun I. The other nominative pronouns are he, she, we, they, and who; the other accusative pronouns are him, her, us, them, and whom. Genitive case is marked on pronouns (my, your, his, her, our, their, whose, its) and also on other noun phrases, thanks to the suffix spelled ’s.

Other than Cookie Monster and Tarzan, most of us effortlessly choose the right case whenever a pronoun is found in its usual place in the tree, next to the governing verb or preposition. But when the pronoun is buried inside a coordination phrase, writers are apt to lose sight of the governor and give the pronoun a different case. Thus in casual speech it’s common for people to say Me and Julio were down by the schoolyard; the me is separated from the verb were by the other words in the coordination (and Julio), and many of us barely hear the clash. Moms and English teachers hear it, though, and they have drilled children to avoid it in favor of Julio and I were down by the schoolyard. Unfortunately, that leads to the opposite kind of error. With coordination, it’s so hard to think in trees that the rationale for the correction never sinks in, and people internalize a string-based rule, “When you want to sound correct, say So-and-so and I rather than Me and so-and-so.” That leads to an error called a hypercorrection, in which people use a nominative pronoun in an accusative coordination:

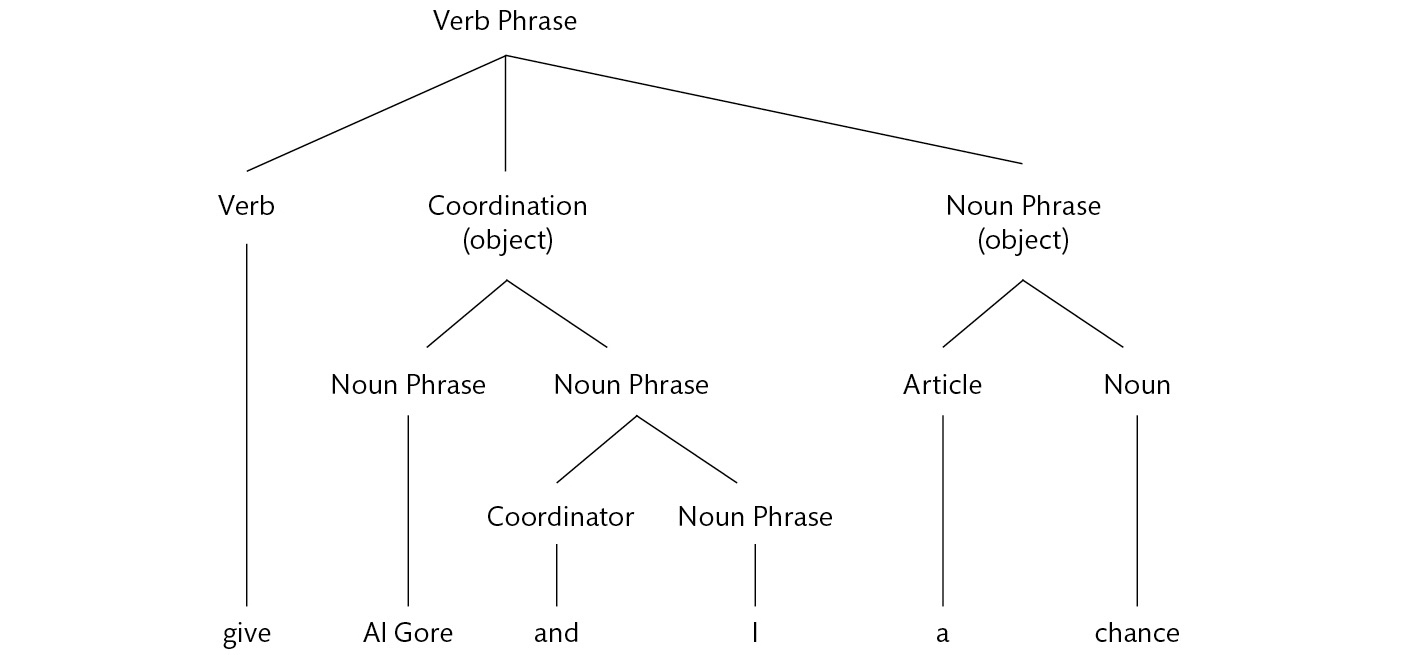

Give Al Gore and I a chance to bring America back.

My mother was once engaged to Leonard Cohen, which makes my siblings and I occasionally indulge in what-if thinking.

For three years, Ellis thought of Jones Point as the ideal spot for he and his companion Sampson, a 9-year-old golden retriever, to fish and play.

Barb decides to plan a second wedding ceremony for she and her husband on Mommies tonight at 8:30 on Channels 7 and 10.

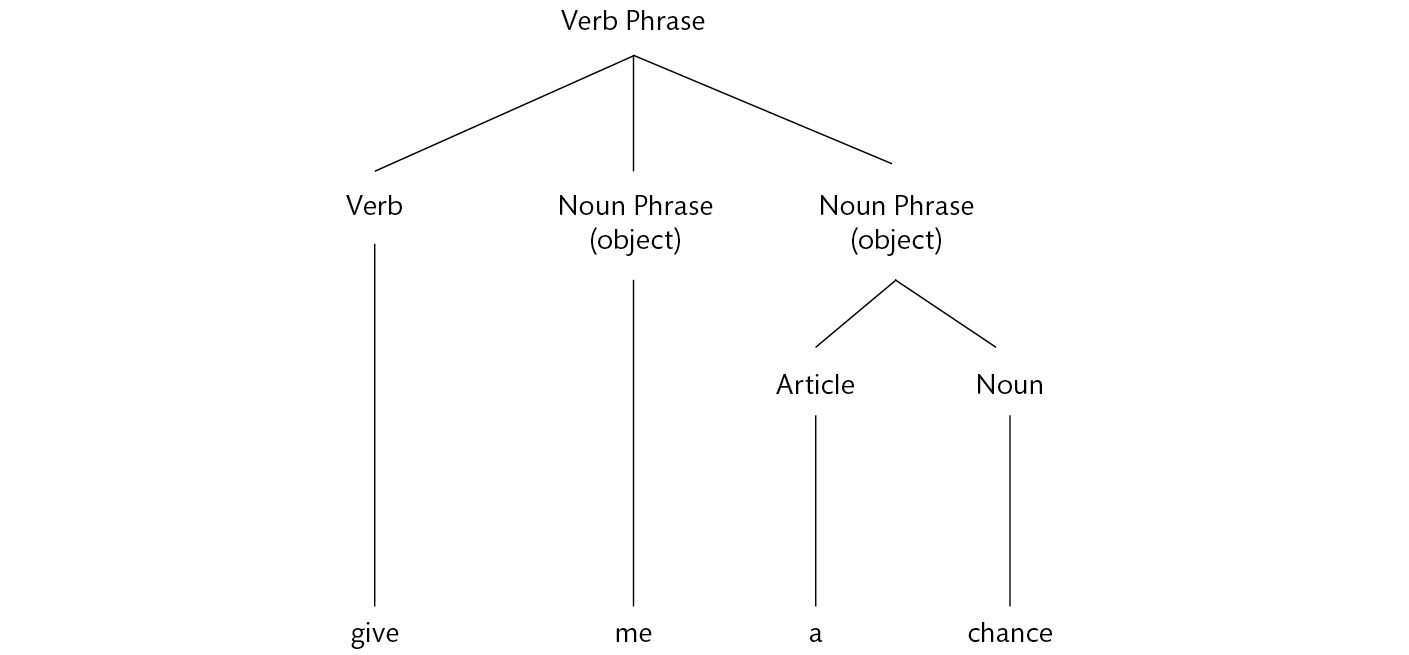

Presumably Bill Clinton, who uttered the first sentence while running for president in 1992, would never have said Give I a chance, because a noun phrase next to a transitive verb is obviously accusative:

But the words Al Gore and separated give from me in the string, and the distance between them befuddled his case-selection circuitry:

To be fair to the forty-second president, who is by all accounts a linguistically sophisticated speaker (as when he famously testified, “It depends on what the meaning of is is”), it’s debatable whether he really made an error here. When enough careful writers and speakers fail to do something that a pencil-and-paper analysis of syntax says they should, it may mean that it’s the pencil-and-paper analysis that is wrong, not the speakers and writers. In chapter 6 we’ll return to this issue when we analyze the despised between you and I, a more common example of the alleged error seen in give Al Gore and I. But for now, let’s assume that the paper-and-pencil analysis is correct. It’s the policy enforced by every editor and composition instructor, and you should understand what it takes to please them.

A similar suspension of disbelief will be necessary for you to master another case of tricky case, the difference between who and whom. You may be inclined to agree with the writer Calvin Trillin when he wrote, “As far as I’m concerned, whom is a word that was invented to make everyone sound like a butler.” But in chapter 6 we’ll see that this is an overstatement. There are times when even nonbutlers need to know their who from their whom, and that will require you, once again, to brush up on your trees.

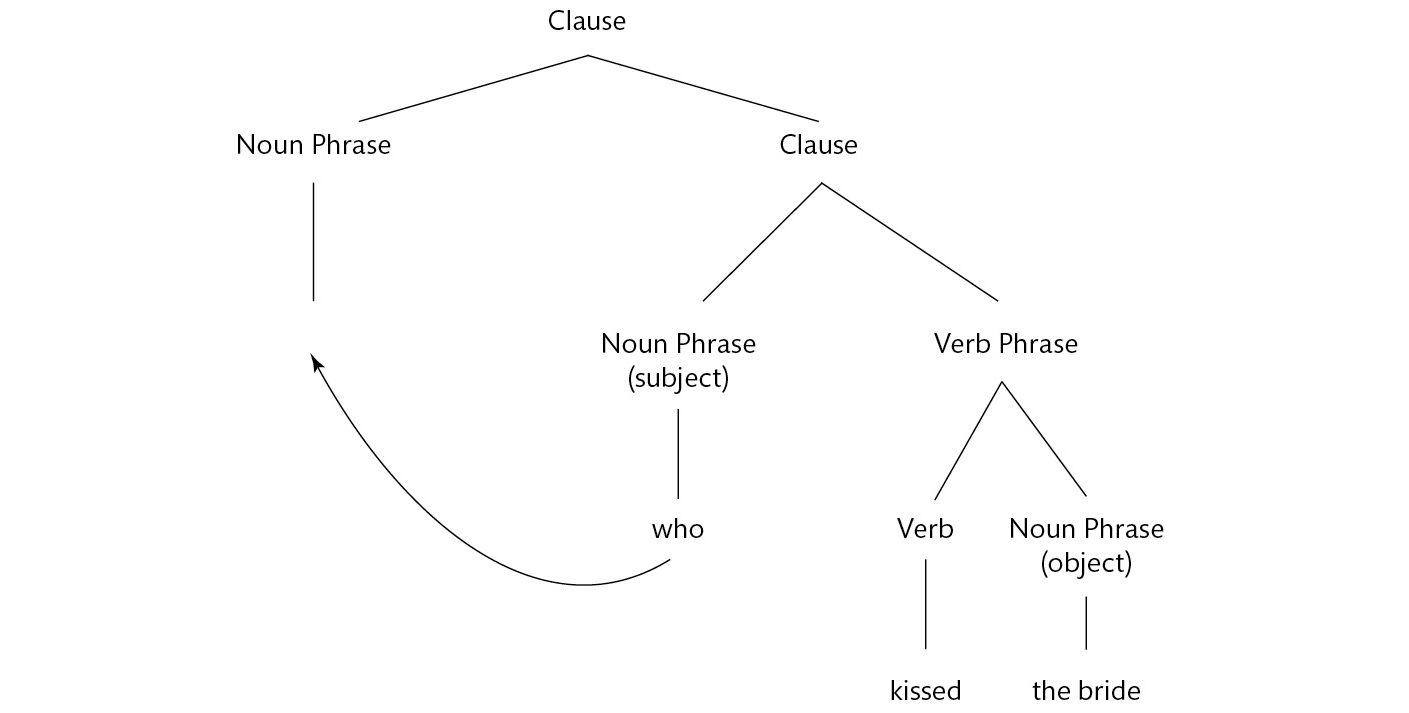

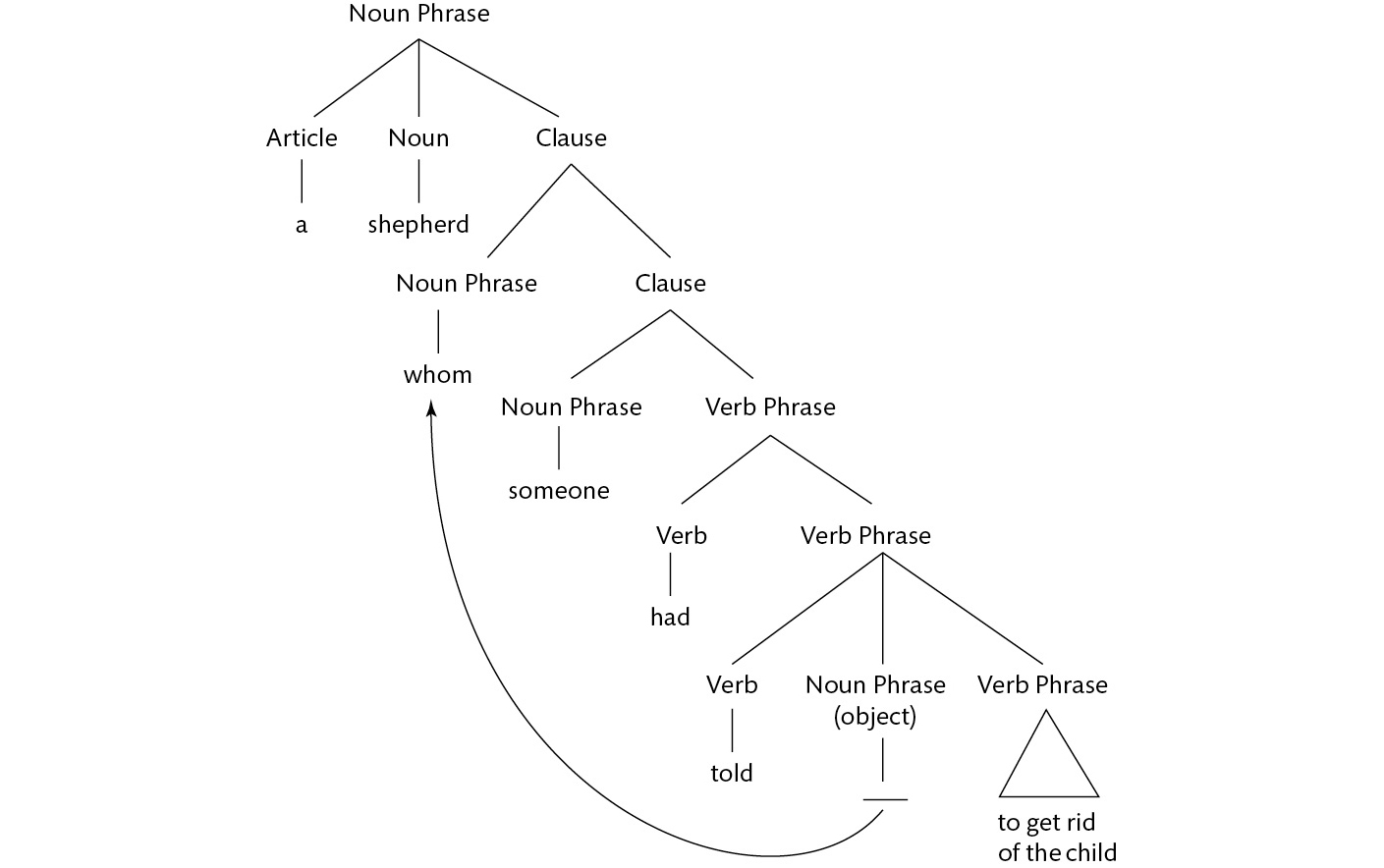

At first glance, the difference is straightforward: who is nominative, like I, she, he, we, and they, and is used for subjects; whom is accusative, like me, her, him, us, and them, and is used for objects. So in theory, anyone who laughs at Cookie Monster when he says Me want cookie should already know when to use who and when to use whom (assuming they have opted to use whom in the first place). We say He kissed the bride, so we ask Who kissed the bride? We say Henry kissed her, so we ask Whom did Henry kiss? The difference can be appreciated by visualizing the wh-words in their deep-structure positions, before they were moved to the front of the sentence, leaving behind a gap.13

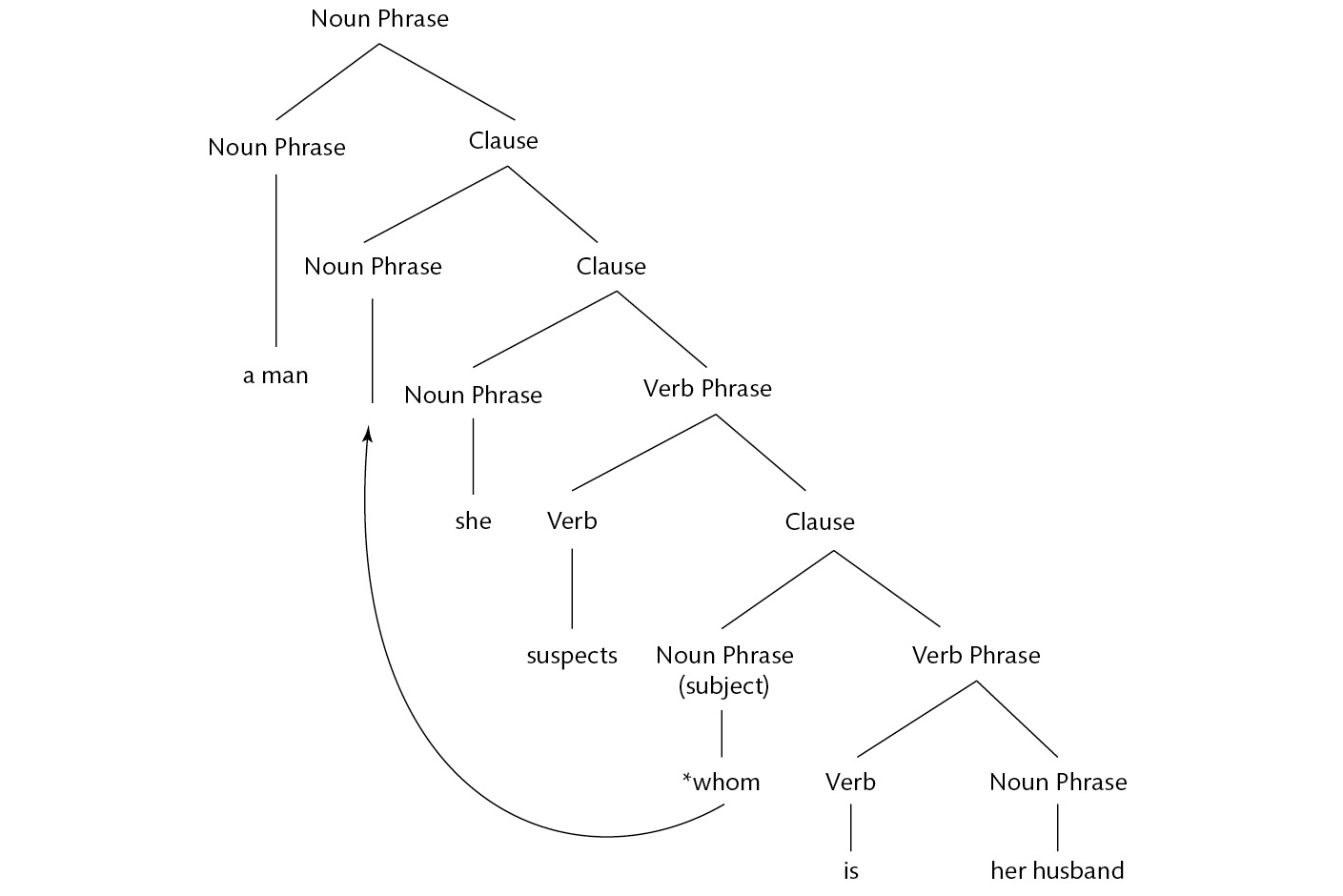

But in practice, our minds can’t take in a whole tree at a glance, so when a sentence gets more complicated, any lapse of attention to the link between the who/whom and the gap can lead to the wrong one being chosen:14

Under the deal, the Senate put aside two nominees for the National Labor Relations Board who the president appointed __ during a Senate recess.

The French actor plays a man whom she suspects __ is her husband, missing since World War II.

The errors could have been avoided by mentally moving the who or whom back into the gap and sounding out the sentence (or, if your intuitions about who and whom are squishy, inserting he or him in the gap instead).

The first replacement yields the president appointed who, which corresponds to the president appointed he, which sounds entirely wrong; therefore it should be whom (corresponding to him) instead. (I’ve inserted an asterisk to remind you that the who doesn’t belong there.) The second yields whom is her husband (or him is her husband), which is just as impossible; it should be who. Again, I’m explaining the official rules so that you will know how to satisfy an editor or work as a butler; in chapter 6 I’ll return to the question of whether the official rules are legitimate and thus whether these really should be counted as errors.

Though tree-awareness can help a writer avoid errors (and, as we shall see, help him make life easy for his readers), I am not suggesting that you literally diagram your sentences. No writer does that. Nor am I even suggesting that you form mental images of trees while you write. The diagrams are just a way to draw your attention to the cognitive entities that are active in your mind as you put together a sentence. The conscious experience of “thinking in trees” does not feel like looking at a tree; it’s the more ethereal sensation of apprehending how words are grouped in phrases and zooming in on the heads of those phrases while ignoring the rest of the clutter. For example, the way to avoid the error The impact of the cuts have not been felt is to mentally strip the phrase the impact of the cuts down to its head, the impact, and then imagine it with have: the error the impact have not been felt will leap right out. Tree-thinking also consists in mentally tracing the invisible filament that links a filler in a sentence to the gap that it plugs, which allows you to verify whether the filler would work if it were inserted there. You un-transform the research the scientists have made __ back into the scientists have made the research; you undo whom she suspects __ is her husband and get she suspects whom is her husband. As with any form of mental self-improvement, you must learn to turn your gaze inward, concentrate on processes that usually run automatically, and try to wrest control of them so that you can apply them more mindfully.

• • •

Once a writer has ensured that the parts of a sentence fit together in a tree, the next worry is whether the reader can recover that tree, which she needs to do to make sense of the sentence. Unlike computer programming languages, where the braces and parentheses that delimit expressions are actually typed into the string for everyone to see, the branching structure of an English sentence has to be inferred from the ordering and forms of the words alone. That imposes two demands on the long-suffering reader. The first is to find the correct branches, a process called parsing. The second is to hold them in memory long enough to dig out the meaning, at which point the wording of the phrase may be forgotten and the meaning merged with the reader’s web of knowledge in long-term memory.15

As the reader works through a sentence, plucking off a word at a time, she is not just threading it onto a mental string of beads. She is also growing branches of a tree upward. When she reads the word the, for example, she figures she must be hearing a noun phrase. Then she can anticipate the categories of words that can complete it; in this case, it’s likely to be a noun. When the word does come in (say, cat), she can attach it to the dangling branch tip.

So every time a writer adds a word to a sentence, he is imposing not one but two cognitive demands on the reader: understanding the word, and fitting it into the tree. This double demand is a major justification for the prime directive “Omit needless words.” I often find that when a ruthless editor forces me to trim an article to fit into a certain number of column-inches, the quality of my prose improves as if by magic. Brevity is the soul of wit, and of many other virtues in writing.

The trick is figuring out which words are “needless.” Often it’s easy. Once you set yourself the task of identifying needless words, it’s surprising how many you can find. A shocking number of phrases that drop easily from the fingers are bloated with words that encumber the reader without conveying any content. Much of my professional life consists of reading sentences like this:

|

Our study participants show a pronounced tendency to be more variable than the norming samples, although this trend may be due partly to the fact that individuals with higher measured values of cognitive ability are more variable in their responses to personality questionnaires. |

a pronounced tendency to be more variable: Is there really a difference between “being more variable” (three words in a three-level, seven-branch tree) and “having a pronounced tendency to be more variable” (eight words, six levels, twenty branches)? Even worse, this trend may be due partly to the fact that burdens an attentive reader with ten words, seven levels, and more than two dozen branches. Total content? Approximately zero. The forty-three-word sentence can easily be reduced to nineteen, which prunes the number of branches even more severely:

|

Our participants are more variable than the norming samples, perhaps because smarter people respond more variably to personality questionnaires. |

Here are a few other morbidly obese phrases, together with leaner alternatives that often mean the same thing:16

|

make an appearance with |

appear with |

|

is capable of being |

can be |

|

is dedicated to providing |

provides |

|

in the event that |

if |

|

it is imperative that we |

we must |

|

brought about the organization of |

organized |

|

significantly expedite the process of |

speed up |

|

on a daily basis |

daily |

|

for the purpose of |

to |

|

in the matter of |

about |

|

in view of the fact that |

since |

|

owing to the fact that |

because |

|

relating to the subject of |

regarding |

|

have a facilitative impact |

help |

|

were in great need of |

needed |

|

at such time as |

when |

|

It is widely observed that X |

X |

Several kinds of verbiage are perennial targets for the delete key. Light verbs such as make, do, have, bring, put, and take often do nothing but create a slot for a zombie noun, as in make an appearance and put on a performance. Why not just use the verb that spawned the zombie in the first place, like appear or perform? A sentence beginning with It is or There is is often a candidate for liposuction: There is competition between groups for resources works just fine as Groups compete for resources. Other globs of verbal fat include the metaconcepts we suctioned out in chapter 2, including matter, view, subject, process, basis, factor, level, and model.

Omitting needless words, however, does not mean cutting out every single word that is redundant in context. As we shall see, many omissible words earn their keep by preventing the reader from making a wrong turn as she navigates her way through the sentence. Others fill out a phrase’s rhythm, which can also make the sentence easier for the reader to parse. Omitting such words is taking the prime directive too far. There is a joke about a peddler who decided to train his horse to get by without eating. “First I fed him every other day, and he did just fine. Then I fed him every third day. Then every fourth day. But just I was getting him down to one meal a week, he died on me!”

The advice to omit needless words should not be confused with the puritanical edict that all writers must pare every sentence down to the shortest, leanest, most abstemious version possible. Even writers who prize clarity don’t do this. That’s because the difficulty of a sentence depends not just on its word count but on its geometry. Good writers often use very long sentences, and they garnish them with words that are, strictly speaking, needless. But they get away with it by arranging the words so that a reader can absorb them a phrase at a time, each phrase conveying a chunk of conceptual structure.

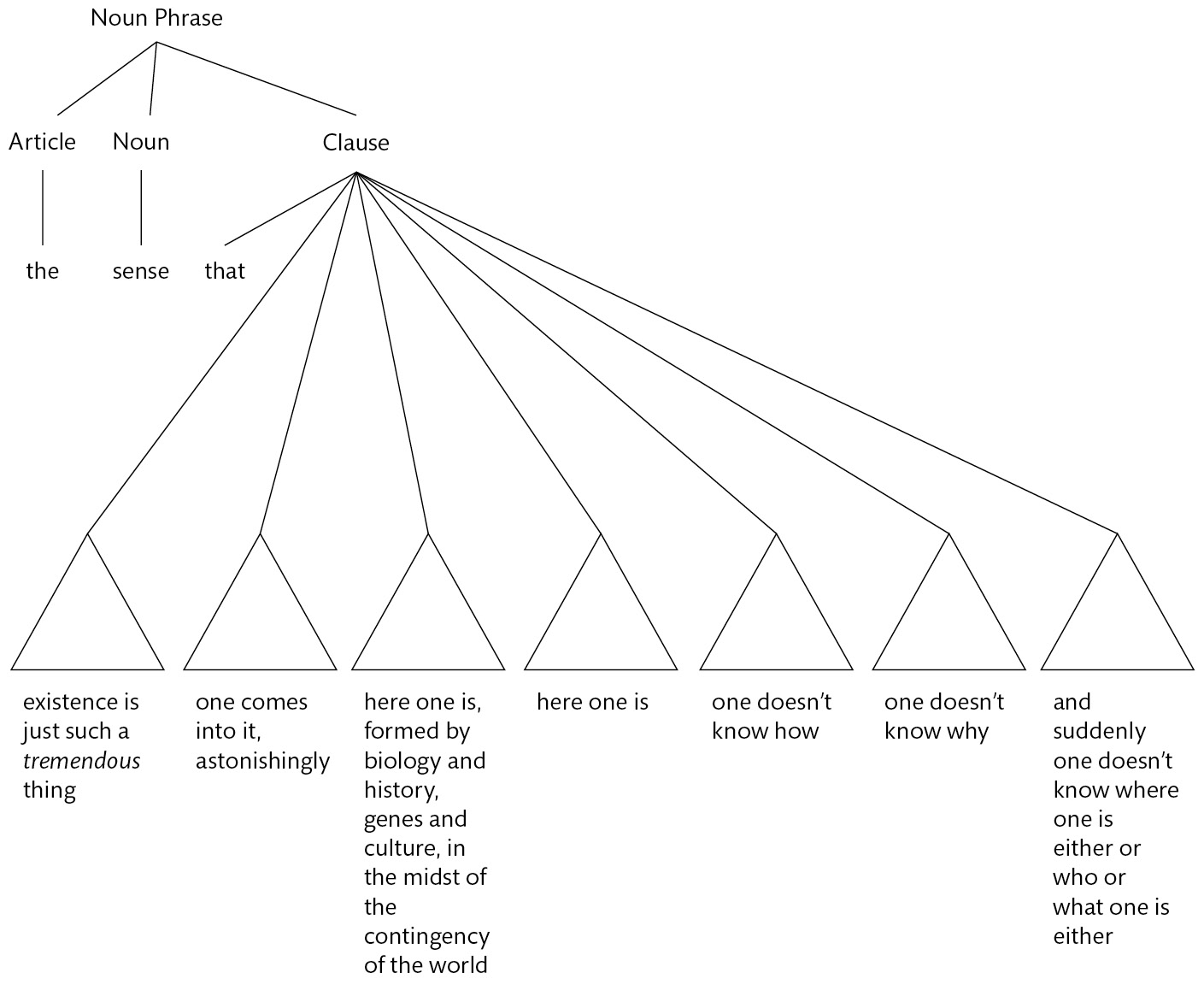

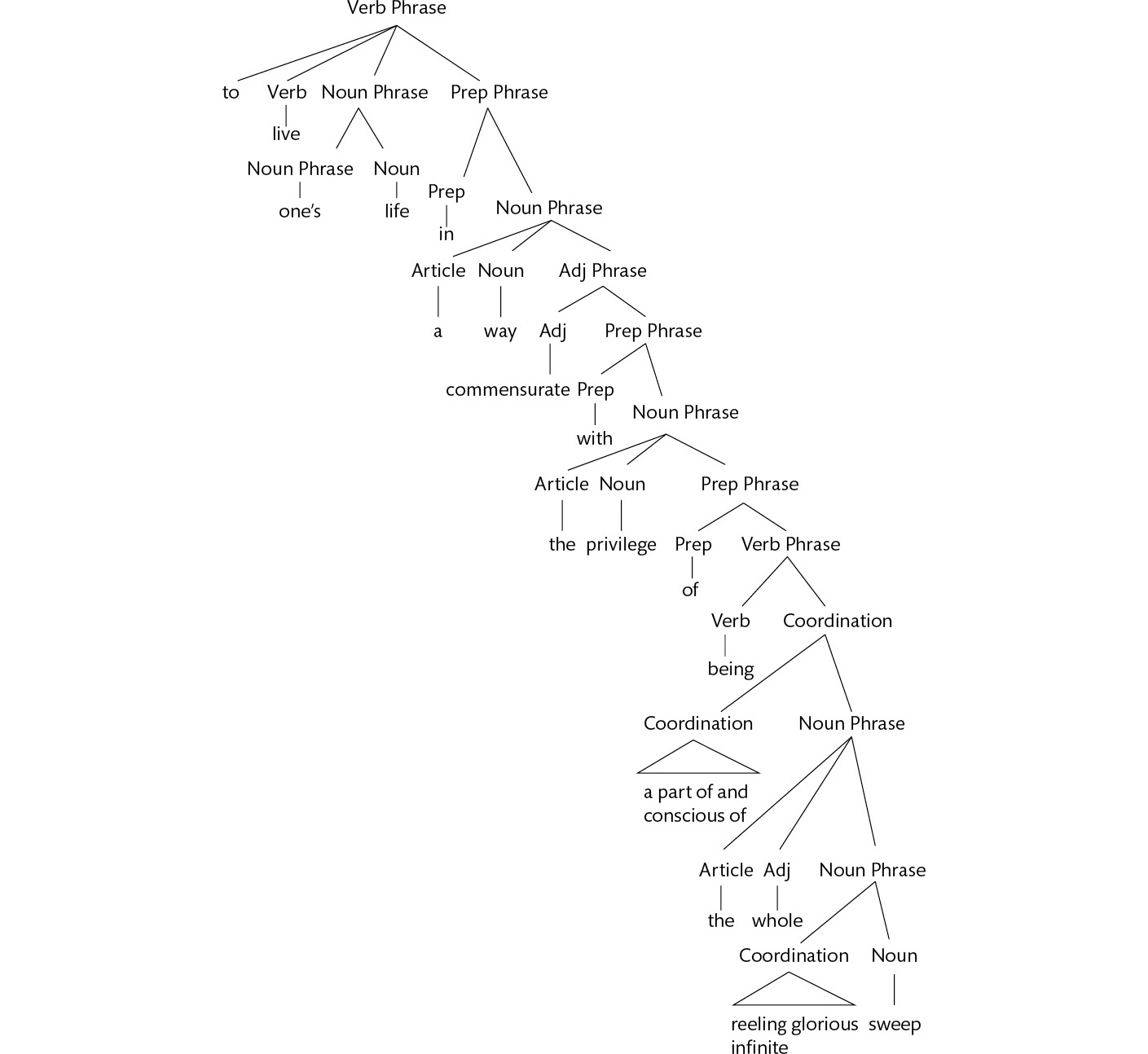

Take this excerpt from a 340-word soliloquy in a novel by Rebecca Goldstein.17 The speaker is a professor who has recently achieved professional and romantic fulfillment and is standing on a bridge on a cold, starry night trying to articulate his wonder at being alive:

Here it is then: the sense that existence is just such a tremendous thing, one comes into it, astonishingly, here one is, formed by biology and history, genes and culture, in the midst of the contingency of the world, here one is, one doesn’t know how, one doesn’t know why, and suddenly one doesn’t know where one is either or who or what one is either, and all that one knows is that one is a part of it, a considered and conscious part of it, generated and sustained in existence in ways one can hardly comprehend, all the time conscious of it, though, of existence, the fullness of it, the reaching expanse and pulsing intricacy of it, and one wants to live in a way that at least begins to do justice to it, one wants to expand one’s reach of it as far as expansion is possible and even beyond that, to live one’s life in a way commensurate with the privilege of being a part of and conscious of the whole reeling glorious infinite sweep, a sweep that includes, so improbably, a psychologist of religion named Cass Seltzer, who, moved by powers beyond himself, did something more improbable than all the improbabilities constituting his improbable existence could have entailed, did something that won him someone else’s life, a better life, a more brilliant life, a life beyond all the ones he had wished for in the pounding obscurity of all his yearnings.

For all its length and lexical exuberance, the sentence is easy to follow, because the reader never has to keep a phrase suspended in memory for long while new words pour in. The tree has been shaped to spread the cognitive load over time with the help of two kinds of topiary. One is a flat branching structure, in which a series of mostly uncomplicated clauses are concatenated side by side with and or with commas. The sixty-two words following the colon, for example, consist mainly of a very long clause which embraces seven self-contained clauses (shown as triangles) ranging from three to twenty words long:

The longest of these embedded clauses, the third and the last, are also flattish trees, each composed of simpler phrases joined side by side with commas or with or.

Even when the sentence structure gets more complicated, a reader can handle the tree, because its geometry is mostly right-branching. In a right-branching tree, the most complicated phrase inside a bigger phrase comes at the end of it, that is, hanging from the rightmost branch. That means that when the reader has to handle the complicated phrase, her work in analyzing all the other phrases is done, and she can concentrate her mental energy on that one. The following twenty-five-word phrase is splayed along a diagonal axis, indicating that it is almost entirely right-branching:

The only exceptions, where the reader has to analyze a downstairs phrase before the upstairs phrase is complete, are the two literary flourishes marked by the triangles.

English is predominantly a right-branching language (unlike, say, Japanese or Turkish), so right-branching trees come naturally to its writers. The full English menu, though, offers them a few left-branching options. A modifier phrase can be moved to the beginning, as in the sentence In Sophocles’ play, Oedipus married his mother (the tree on page 82 displays the complicated left branch). These front-loaded modifiers can be useful in qualifying a sentence, in tying it to information mentioned earlier, or simply in avoiding the monotony of having one right-branching sentence after another. As long as the modifier is short, it poses no difficulty for the reader. But if it starts to get longer it can force a reader to entertain a complicated qualification before she has any idea what it is qualifying. In the following sentence, the reader has to parse thirty-four words before she gets to the part that tells her what the sentence is about, namely policymakers:18

|

Because most existing studies have examined only a single stage of the supply chain, for example, productivity at the farm, or efficiency of agricultural markets, in isolation from the rest of the supply chain, policymakers have been unable to assess how problems identified at a single stage of the supply chain compare and interact with problems in the rest of the supply chain. |

Another common left-branching construction consists of a noun modified by a complicated phrase that precedes it:

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Failed password security question answer attempts limit

The US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control

Ann E. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government Michael Sandel

T-fal Ultimate Hard Anodized Nonstick Expert Interior Thermo-Spot Heat Indicator Anti-Warp Base Dishwasher Safe 12-Piece Cookware Set

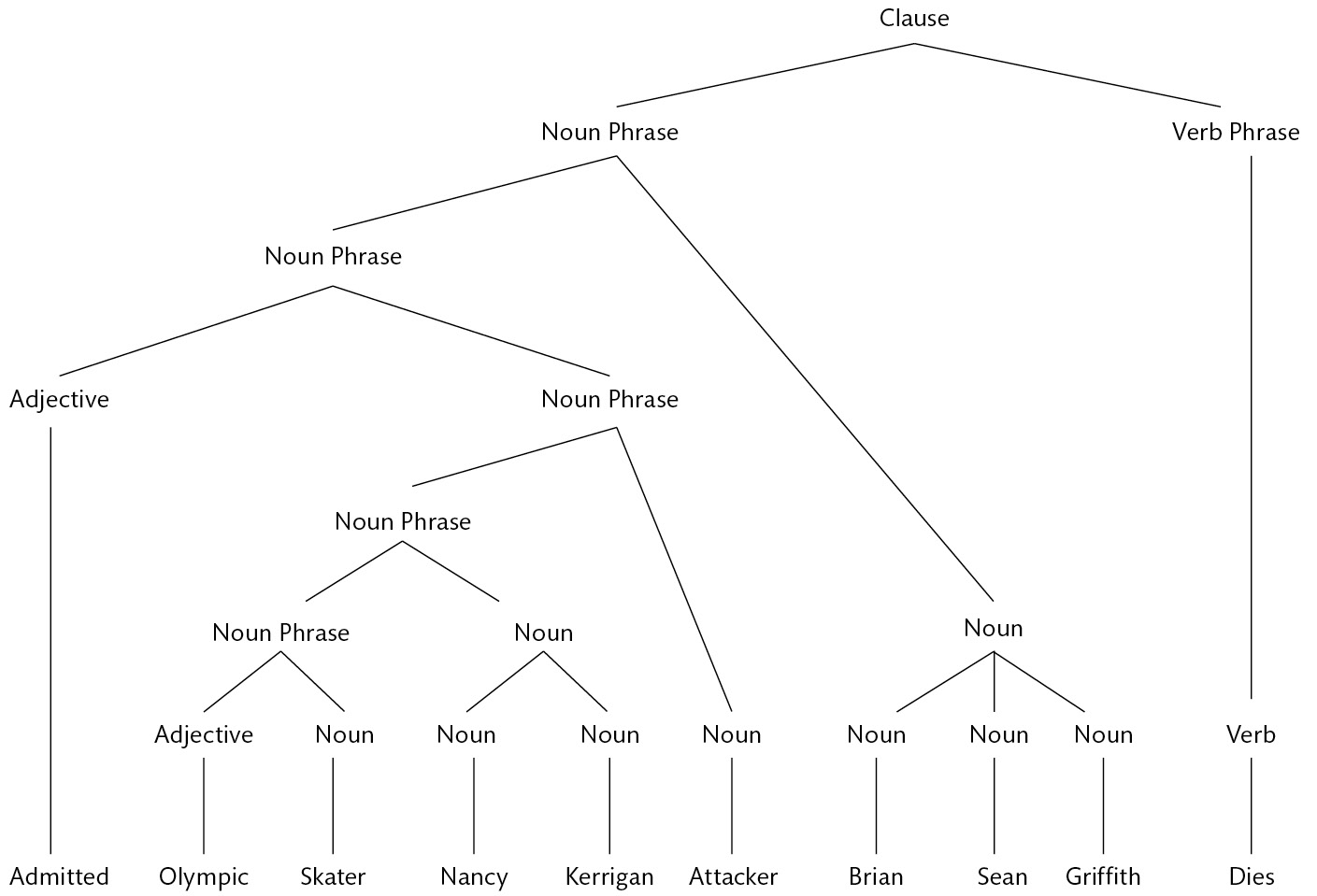

Academics and bureaucrats concoct them all too easily; I once came up with a monstrosity called the relative passive surface structure acceptability index. If the left branch is slender enough, it is generally understandable, albeit top-heavy, with all those words to parse before one arrives at the payoff. But if the branch is bushy, or if one branch is packed inside another, a left-branching structure can give the reader a headache. The most obvious examples are iterated possessives such as my mother’s brother’s wife’s father’s cousin. Left-branching trees are a hazard of headline writing. Here’s one that reported the death of a man who achieved fifteen minutes of fame in 1994 for hatching a plot to get Tonya Harding onto the US Olympic skating team by clubbing her main rival on the knee:

|

ADMITTED OLYMPIC SKATER NANCY KERRIGAN ATTACKER BRIAN SEAN GRIFFITH DIES |

A blogger posted a commentary entitled “Admitted Olympic Skater Nancy Kerrigan Attacker Brian Sean Griffith Web Site Obituary Headline Writer Could Have Been Clearer.” The lack of clarity in the original headline was the result of its left-branching geometry: it has a ramified left branch (all the material before Dies), which itself contains a ramified left branch (all the material before Brian Sean Griffith), which in turn contains a ramified left branch (all the material before Attacker):19

Linguists call these constructions “noun piles.” Here are few others that have been spotted by contributors to the forum Language Log:

NUDE PIC ROW VICAR RESIGNS

TEXTING DEATH CRASH PEER JAILED

BEN DOUGLAS BAFTA RACE ROW HAIRDRESSER JAMES BROWN “SORRY”

FISH FOOT SPA VIRUS BOMBSHELL

CHINA FERRARI SEX ORGY DEATH CRASH

My favorite explanation of the difference in difficulty between flat, right-branching, and left-branching trees comes from Dr. Seuss’s Fox in Socks, who takes a flat clause with three branches, each containing a short right-branching clause, and recasts it as a single left-branching noun phrase: “When beetles fight these battles in a bottle with their paddles and the bottle’s on a poodle and the poodle’s eating noodles, they call this a muddle puddle tweetle poodle beetle noodle bottle paddle battle.”

As much of a battle as left-branching structures can be, they are nowhere near as muddled as center-embedded trees, those in which a phrase is jammed into the middle of a larger phrase rather than fastened to its left or right edge. In 1950 the linguist Robert A. Hall wrote a book called Leave Your Language Alone. According to linguistic legend, it drew a dismissive review entitled “Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone.” The author was invited to reply, and wrote a rebuttal called—of course—“Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone.”

Unfortunately, it’s only a legend; the recursive title was dreamed up by the linguist Robin Lakoff for a satire of a linguistics journal.20 But it makes a serious point: a multiply center-embedded sentence, though perfectly grammatical, cannot be parsed by mortal humans.21 Though I’m sure you can follow an explanation on why the string Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone has a well-formed tree, you could never recover it from the string. The brain’s sentence parser starts to thrash when faced with the successive leaves at the beginning, and it crashes altogether when it gets to the pile of alones at the end.

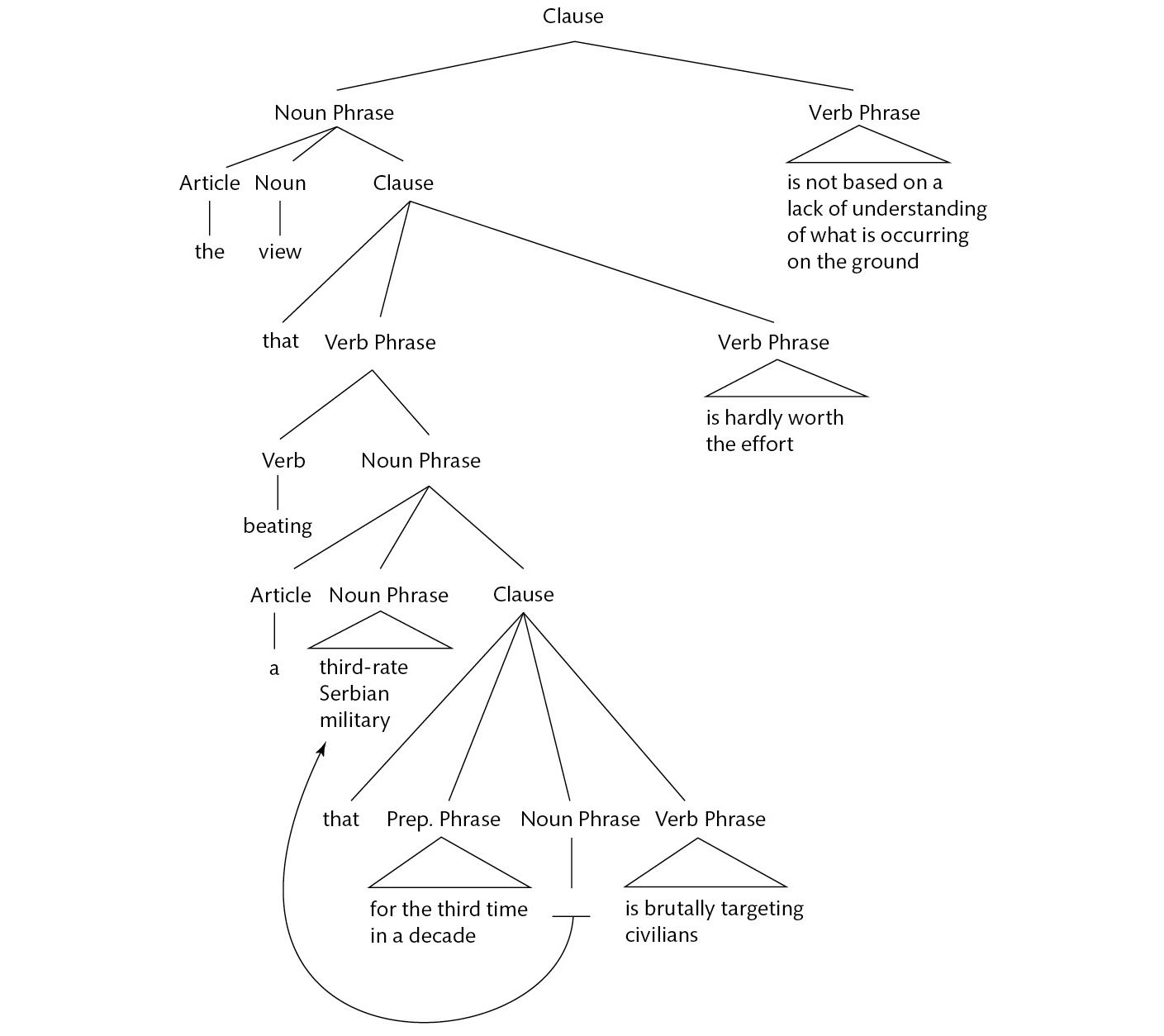

Center-embedded constructions are not just linguistic in-jokes; they are often the diagnosis for what we sense as “convoluted” or “tortuous” syntax. Here is an example from a 1999 editorial on the Kosovo crisis (entitled “Aim Straight at the Target: Indict Milosevic”) by the senator and former presidential candidate Bob Dole:22

|

The view that beating a third-rate Serbian military that for the third time in a decade is brutally targeting civilians is hardly worth the effort is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground. |

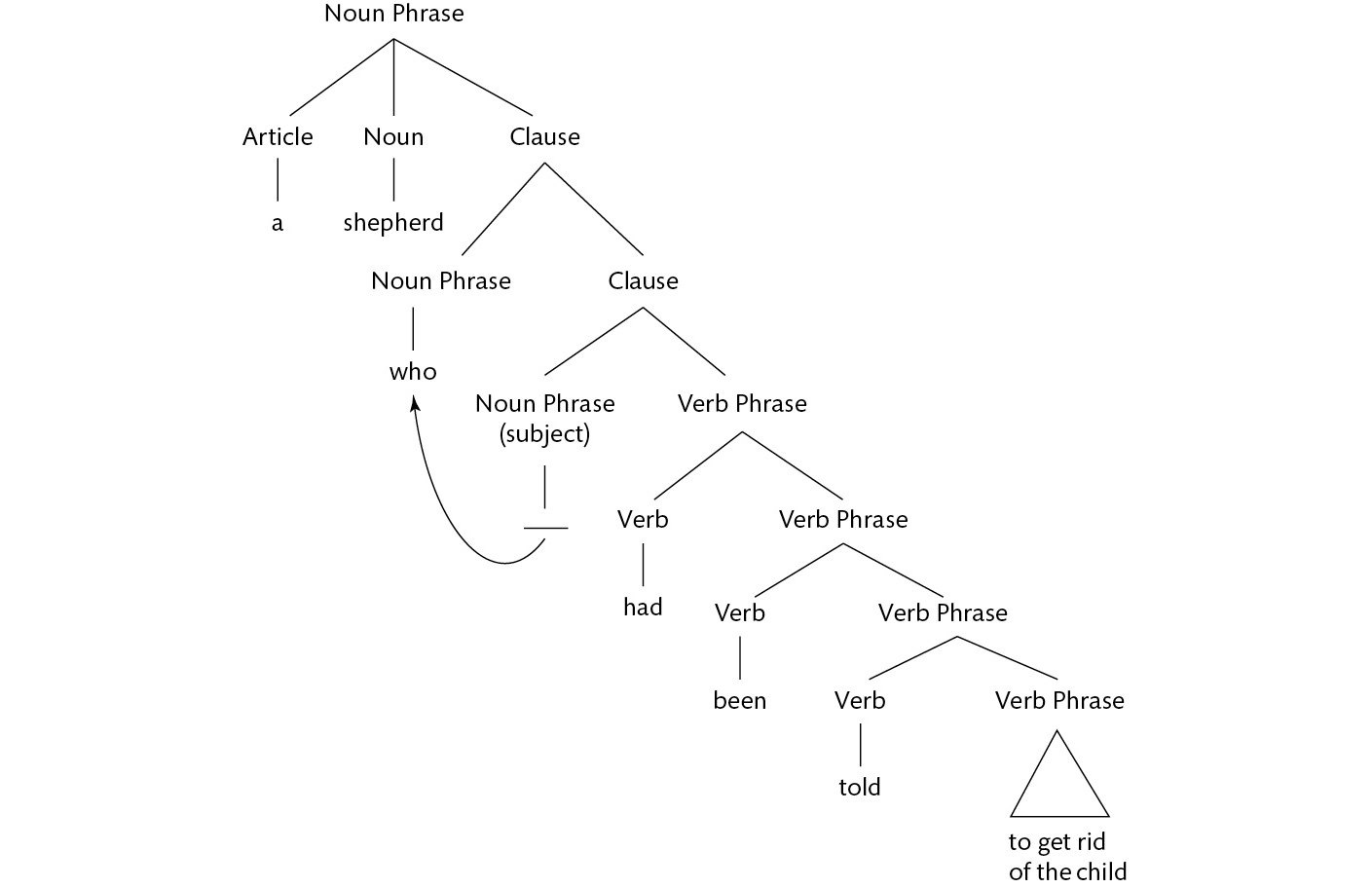

As with Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone, this sentence ends bafflingly, with three similar phrases in a row: is brutally targeting civilians, is hardly worth the effort, is not based on a lack of understanding. Only with a tree diagram can you figure it out:

The first of the three is-phrases, is brutally targeting civilians, is the most deeply embedded one; it is part of a relative clause that modifies third-rate Serbian military. That entire phrase (the military that is targeting the civilians) is the object of the verb beating. That still bigger phrase (beating the military) is the subject of a sentence whose predicate is the second is-phrase, is hardly worth the effort. That sentence in turn belongs to a clause which spells out the content of the noun view. The noun phrase containing view is the subject of the third is-phrase, is not based on a lack of understanding.

In fact, the reader’s misery begins well before she plows into the pile of is-phrases at the end. Midway through the sentence, while she is parsing the most deeply embedded clause, she has to figure out what the third-rate Serbian military is doing, which she can only do when she gets to the gap before is brutally targeting civilians nine words later (the link between them is shown as a curved arrow). Recall that filling gaps is a chore which arises when a relative clause introduces a filler noun and leaves the reader uncertain about what role it is going to play until she finds a gap for it to fill. As she is waiting to find out, new material keeps pouring in (for the third time in a decade), making it easy for her to lose track of how to join them up.

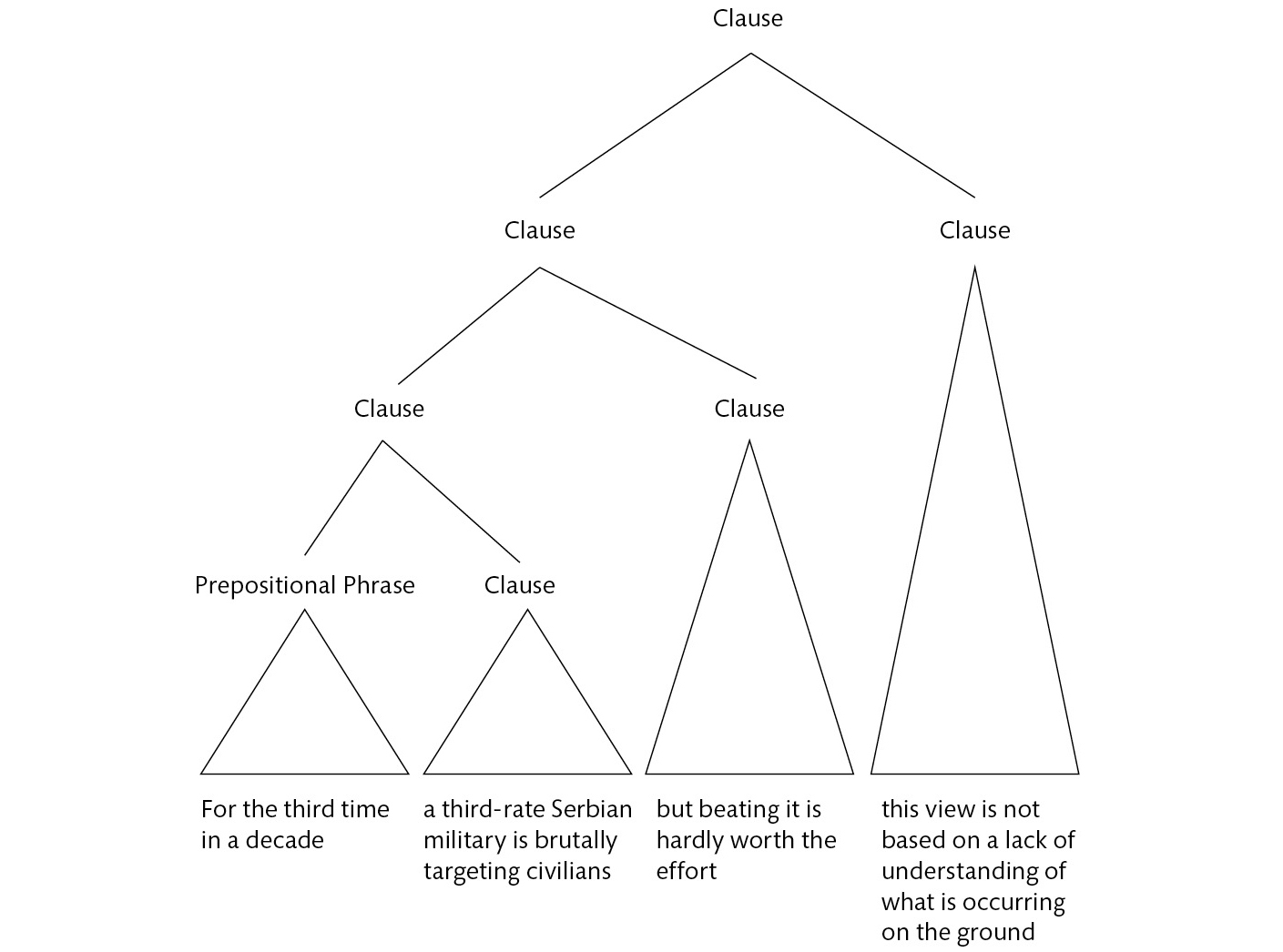

Can this sentence be saved? If you insist on keeping it as a single sentence, a good start is to disinter each embedded clause and place it side by side with the clause that contained it, turning a deeply center-embedded tree into a relatively flat one. This would give us For the third time in a decade, a third-rate Serbian military is brutally targeting civilians, but beating it is hardly worth the effort; this view is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

It’s still not a great sentence, but now that the tree is flatter one can see how to lop off entire branches and make them into separate sentences. Splitting in two (or three or four) is often the best way to tame a sentence that has grown unruly. In the following chapter, which is about sequences of sentences rather than individual sentences, we’ll see how to do that.

How does a writer manage to turn out such tortuous syntax? It happens when he shovels phrase after phrase onto the page in the order in which each one occurs to him. The problem is that the order in which thoughts occur to the writer is different from the order in which they are easily recovered by a reader. It’s a syntactic version of the curse of knowledge. The writer can see the links among the concepts in his internal web of knowledge, and has forgotten that a reader needs to build an orderly tree to decipher them from his string of words.

In chapter 3 I mentioned two ways to improve your prose—showing a draft to someone else, and revisiting it after some time has passed—and both can allow you to catch labyrinthine syntax before inflicting it on your readers. There’s a third time-honored trick: read the sentence aloud. Though the rhythm of speech isn’t the same as the branching of a tree, it’s related to it in a systematic way, so if you stumble as you recite a sentence, it may mean you’re tripping on your own treacherous syntax. Reading a draft, even in a mumble, also forces you to anticipate what your readers will be doing as they understand your prose. Some people are surprised by this advice, because they think of the claim by speed-reading companies that skilled readers go directly from print to thought. Perhaps they also recall the stereotype from popular culture in which unskilled readers move their lips when they read. But laboratory studies have shown that even skilled readers have a little voice running through their heads the whole time.23 The converse is not true—you might zip through a sentence of yours that everyone else finds a hard slog—but prose that’s hard for you to pronounce will almost certainly be hard for someone else to comprehend.

• • •

Earlier I mentioned that holding the branches of a tree in memory is one of the two cognitive challenges in parsing a sentence. The other is growing the right branches, that is, inferring how the words are supposed to join up in phrases. Words don’t come with labels like “I’m a noun” or “I’m a verb.” Nor is the boundary where one phrase leaves off and the next one begins marked on the page. The reader has to guess, and it’s up to the writer to ensure that the guesses are correct. They aren’t always. A few years ago a member of a consortium of student groups at Yale put out this press release:

I’m coordinating a huge event for Yale University which is titled “Campus-Wide Sex Week.”

The week involves a faculty lecture series with topics such as transgender issues: where does one gender end and the other begin, the history of romance, and the history of the vibrator. Student talks on the secrets of great sex, hooking up, and how to be a better lover and a student panel on abstainance. . . . A faculty panel on sex in college with four professors. a movie film festival (sex fest 2002) and a concert with local bands and yale bands. . . .

The event is going to be huge and all of campus is going to be involved.

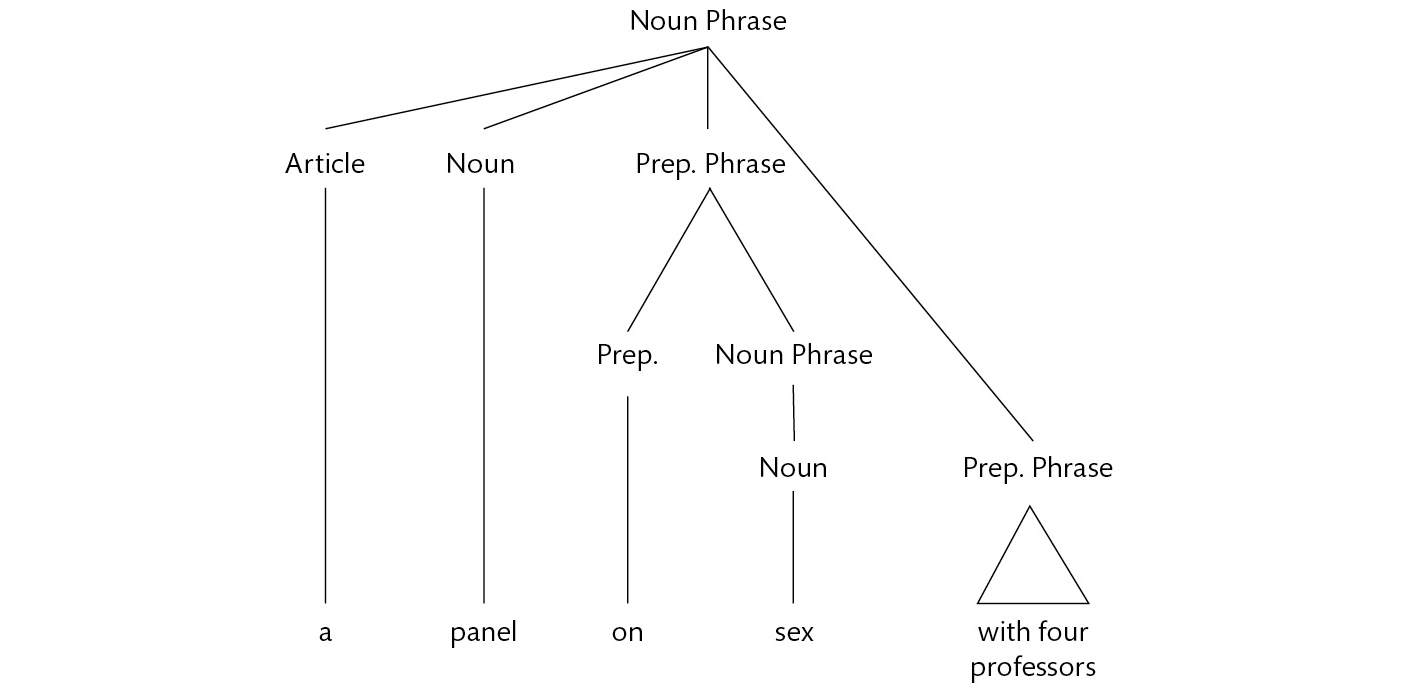

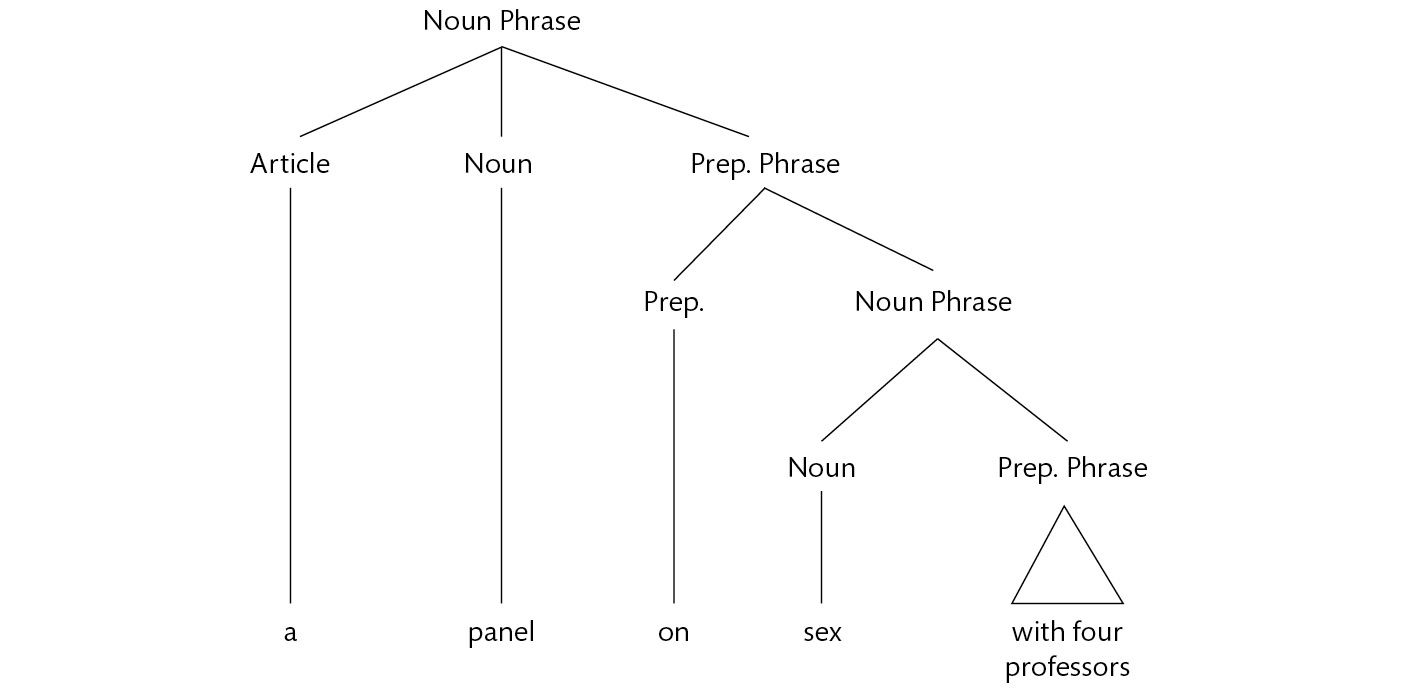

One recipient, the writer Ron Rosenbaum, commented, “One of my first thoughts on reading this was that before Yale (my beloved alma mater) had a Sex Week it ought to institute a gala Grammar and Spelling Week. In addition to ‘abstainance’ (unless it was a deliberate mistake in order to imply that ‘Yale puts the stain in abstinence’) there was that intriguing ‘faculty panel on sex in college with four professors,’ whose syntax makes it sound more illicit than it was probably intended to be.”24

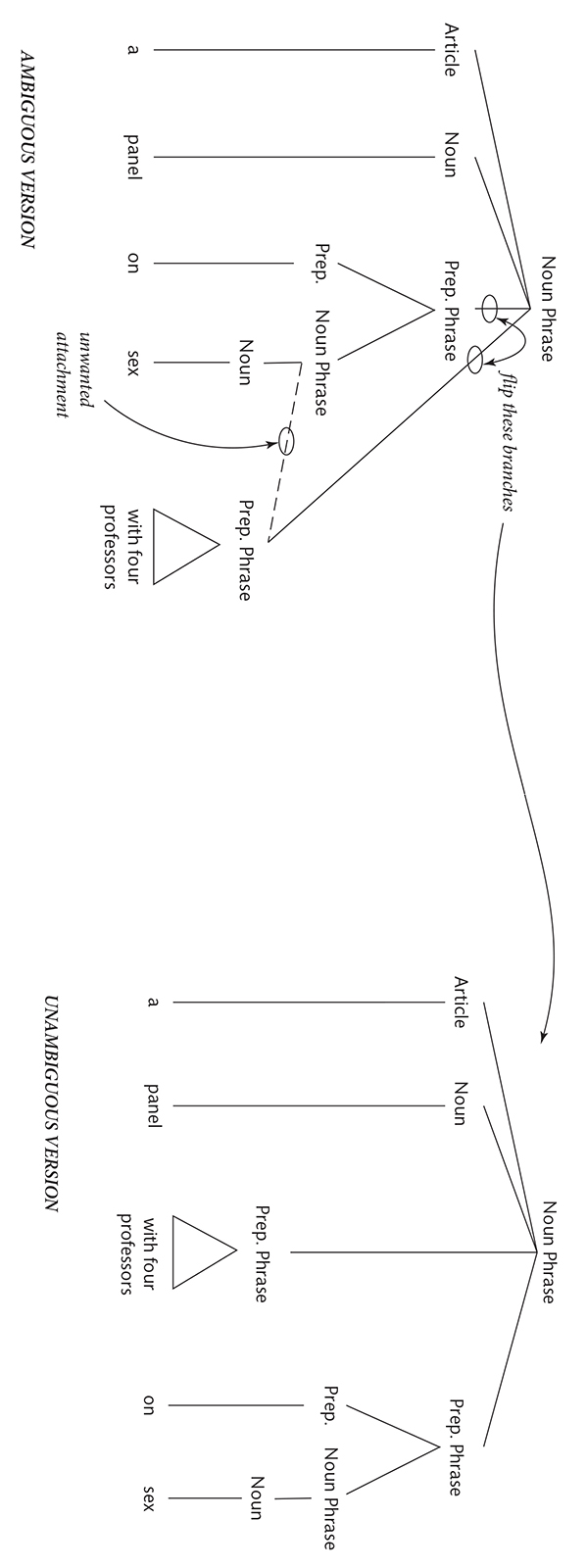

The student coordinator had blundered into the problem of syntactic ambiguity. In the simpler case of lexical ambiguity, an individual word has two meanings, as in the headlines SAFETY EXPERTS SAY SCHOOL BUS PASSENGERS SHOULD BE BELTED and NEW VACCINE MAY CONTAIN RABIES. In syntactic ambiguity, there may be no single word that is ambiguous, but the words can be interconnected into more than one tree. The organizer of Sex Week at Yale intended the first tree, which specifies a panel with four professors: Rosenbaum parsed it with the second tree, which specifies sex with four professors:

Syntactic ambiguities are the source of frequently emailed bloopers in newspaper headlines (LAW TO PROTECT SQUIRRELS HIT BY MAYOR), medical reports (The young man had involuntary seminal fluid emission when he engaged in foreplay for several weeks), classified ads (Wanted: Man to take care of cow that does not smoke or drink), church bulletins (This week’s youth discussion will be on teen suicide in the church basement), and letters of recommendation (I enthusiastically recommend this candidate with no qualifications whatsoever).25 These Internet memes may seem too good to be true, but I’ve come across a few on my own, and colleagues have sent me others:

Prosecutors yesterday confirmed they will appeal the “unduly lenient” sentence of a motorist who escaped prison after being convicted of killing a cyclist for the second time.

THE PUBLIC VALUES FAILURES OF CLIMATE SCIENCE IN THE US

A teen hunter has been convicted of second-degree manslaughter for fatally shooting a hiker on a popular Washington state trail he had mistaken for a bear.

MANUFACTURING DATA HELPS INVIGORATE WALL STREET26

THE TROUBLE WITH TESTING MANIA

For every ambiguity that is inadvertently funny or ironic, there must be thousands that are simply confusing. The reader has to scan the sentence several times to figure out which of two meanings the writer intended, or worse, she may come away with the wrong meaning without realizing it. Here are three I noticed in just a few days of reading:

|

The senator plans to introduce legislation next week that fixes a critical flaw in the military’s handling of assault cases. The measure would replace the current system of adjudicating sexual assault by taking the cases outside a victim’s chain of command. [Is it the new measure that takes the cases outside the chain of command, or is it the current system?] |

|

China has closed a dozen websites, penalized two popular social media sites, and detained six people for circulating rumors of a coup that rattled Beijing in the middle of its worst high-level political crisis in years. [Did the coup rattle Beijing, or did rumors?] |

|

Last month, Iran abandoned preconditions for resuming international negotiations over its nuclear programs that the West had considered unacceptable. [Were the preconditions unacceptable, or the negotiations, or the programs?] |

And for every ambiguity that yields a coherent (but unintended) interpretation of the whole sentence, there must be thousands which trip up the reader momentarily, forcing her to backtrack and re-parse a few words. Psycholinguists call these local ambiguities “garden paths,” from the expression “to lead someone up the garden path,” that is, to mislead him. They have made an art form out of grammatical yet unparsable sentences:27

The horse raced past the barn fell. [= “The horse that was raced (say, by a jockey) past the barn was the horse that fell.”]

The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

Cotton clothing is made from is grown in Egypt.

Fat people eat accumulates.

The prime number few.

When Fred eats food gets thrown.

I convinced her children are noisy.

She told me a little white lie will come back to haunt me.

The old man the boat.

Have the students who failed the exam take the supplementary.

Most garden paths in everyday writing, unlike the ones in textbooks, don’t bring the reader to a complete standstill; they just delay her for a fraction of a second. Here are a few I’ve collected recently, with an explanation of what led me astray in each case:

|

During the primary season, Mr. Romney opposed the Dream Act, proposed legislation that would have allowed many young illegal immigrants to remain in the country. [Romney opposed the Act and also proposed some legislation? No, the Act is a piece of legislation that had been proposed.] |

|

Those who believe in the necessity of nuclear weapons as a deterrent tool fundamentally rely on the fear of retaliation, whereas those who don’t focus more on the fear of an accidental nuclear launch that might lead to nuclear war. [Those who don’t focus? No, those who don’t believe in the necessity of a nuclear deterrent.] |

|

The data point to increasing benefits with lower and lower LDL levels, said Dr. Daniel J. Rader. [Is this sentence about a data point? No, it’s about data which point to something.] |

|

But the Supreme Court’s ruling on the health care law last year, while upholding it, allowed states to choose whether to expand Medicaid. Those that opted not to leave about eight million uninsured people who live in poverty without any assistance at all. [Opted not to leave? No, opted not to expand.] |

Garden paths can turn the experience of reading from an effortless glide through a sentence to a tedious two-step of little backtracks. The curse of knowledge hides them from the writer, who therefore must put some effort into spotting and extirpating them. Fortunately, garden-pathing is a major research topic in psycholinguistics, so we know what to look for. Experimenters have recorded readers’ eye movements and brainwaves as they work their way through sentences, and have identified both the major lures that lead readers astray and the helpful signposts that guide them in the right direction.28

Prosody. Most garden paths exist only on the printed page. In speech, the prosody of a sentence (its melody, rhythm, and pausing) eliminates any possibility of the hearer taking a wrong turn: The man who HUNTS . . . ducks out on weekends; The PRIME . . . number few. That’s one of the reasons a writer should mutter, mumble, or orate a draft of his prose to himself, ideally after enough time has elapsed that it is no longer familiar. He may find himself trapped in his own garden paths.

Punctuation. A second obvious way to avoid garden paths is to punctuate a sentence properly. Punctuation, together with other graphical indicators such as italics, capitalization, and spacing, developed over the history of printed language to do two things. One is to provide the reader with hints about prosody, thus bringing writing a bit closer to speech. The other is to provide her with hints about the major divisions of the sentence into phrases, thus eliminating some of the ambiguity in how to build the tree. Literate readers rely on punctuation to guide them through a sentence, and mastering the basics is a nonnegotiable requirement for anyone who writes.

Many of the silliest ambiguities in the Internet memes come from newspaper headlines and magazine tag lines precisely because they have been stripped of all punctuation. Two of my favorites are MAN EATING PIRANHA MISTAKENLY SOLD AS PET FISH and RACHAEL RAY FINDS INSPIRATION IN COOKING HER FAMILY AND HER DOG. The first is missing the hyphen that bolts together the pieces of the compound word that was supposed to remind readers of the problem with piranhas, man-eating. The second is missing the commas that delimit the phrases making up the list of inspirations: cooking, her family, and her dog.

Generous punctuation would also take the fun out of some of the psycholinguists’ garden path sentences, such as When Fred eats food gets thrown. And the press release on Sex Week at Yale would have been easier to parse had the student authors spent less time studying the history of the vibrator and more time learning how to punctuate. (Why is the history of romance a transgender issue? What are the secrets of how to be a student panel?)

Unfortunately, even the most punctilious punctuation is not informative enough to eliminate all garden paths. Modern punctuation has a grammar of its own, which corresponds neither to the pauses in speech nor to the boundaries in syntax.29 It would be nice, for example, if we could clear things up by writing Fat people eat, accumulates, or I convinced her, children are noisy. But as we shall see in chapter 6, using a comma to separate a subject from its predicate or a verb from one of its complements is among the most grievous sins of mispunctuation. You can get away with it when the need for disambiguation becomes an emergency, as in George Bernard Shaw’s remark “He who can, does; he who cannot, teaches” (and in Woody Allen’s addendum “And he who cannot teach, teaches gym”). But in general the divisions between the major parts of a clause, such as subject and predicate, are comma-free zones, no matter how complex the syntax.

Words that signal syntactic structure. Another way to prevent garden paths is to give some respect to the apparently needless little words which don’t contribute much to the meaning of a sentence and are in danger of ending up on the cutting-room floor, but which can earn their keep by marking the beginnings of phrases. Foremost among them are the subordinator that and relative pronouns like which and who, which can signal the beginning of a relative clause. In some phrases, these are “needless words” that can be deleted, as in the man [whom] I love and things [that] my father said, sometimes taking is or are with them, as in A house [which is] divided against itself cannot stand. The deletions are tempting to a writer because they tighten up a sentence’s rhythm and avoid the ugly sibilance of which. But if the which-hunt is prosecuted too zealously, it may leave behind a garden path. Many of the textbook examples become intelligible when the little words are restored: The horse which was raced past the barn fell; Fat which people eat accumulates.

Oddly enough, one of the most easily overlooked disambiguating words in English is the most frequent word in the language: the lowly definite article the. The meaning of the is not easy to state (we’ll get to it in the next chapter), but it could not be a clearer marker of syntax: when a reader encounters it, she has indubitably entered a noun phrase. The definite article can be omitted before many nouns, but the result can feel claustrophobic, as if noun phrases keep bumping into you without warning:

|

If selection pressure on a trait is strong, then alleles of large effect are likely to be common, but if selection pressure is weak, then existing genetic variation is unlikely to include alleles of large effect. |

If the selection pressure on a trait is strong, then alleles of large effect are likely to be common, but if the selection pressure is weak, then the existing genetic variation is unlikely to include alleles of large effect. |

|

Mr. Zimmerman talked to police repeatedly and willingly. |

Mr. Zimmerman talked to the police repeatedly and willingly. |

This feeling that a definite noun phrase without the does not properly announce itself may underlie the advice of many writers and editors to avoid the journalese construction on the left below (sometimes called the false title) and introduce the noun phrase with a dignified the, even if it is semantically unnecessary:

|

People who have been interviewed on the show include novelist Zadie Smith and cellist Yo-Yo Ma. |

People who have been interviewed on the show include the novelist Zadie Smith and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma. |

|

As linguist Geoffrey Pullum has noted, sometimes the passive voice is necessary. |

As the linguist Geoffrey Pullum has noted, sometimes the passive voice is necessary. |

Though academic prose is often stuffed with needless words, there is also a suffocating style of technical writing in which the little words like the, are, and that have been squeezed out. Restoring them gives the reader some breathing space, because the words guide her into the appropriate phrase and she can attend to the meaning of the content words without simultaneously having to figure out what kind of phrase she is in:

|

Evidence is accumulating that most previous publications claiming genetic associations with behavioral traits are false positives, or at best vast overestimates of true effect sizes. |

Evidence is accumulating that most of the previous publications that claimed genetic associations with behavioral traits are false positives, or at best are vast overestimates of the true effect sizes. |

Another tradeoff between brevity and clarity may be seen in the placement of modifiers. A noun can be modified either by a prepositional phrase on the right or by a naked noun on the left: data on manufacturing versus manufacturing data, strikes by teachers versus teacher strikes, stockholders in a company versus company stockholders. The little preposition can make a big difference. The headline MANUFACTURING DATA HELPS INVIGORATE WALL STREET could have used one, and a preposition would also have come in handy in TEACHER STRIKES IDLE KIDS and TEXTRON MAKES OFFER TO SCREW COMPANY STOCKHOLDERS.

Frequent strings and senses. Yet another lure into a garden path comes from the statistical patterns of the English language, in which certain words are likely to precede or follow others.30 As we become fluent readers we file away in memory tens of thousands of common word pairs, such as horse race, hunt ducks, cotton clothing, fat people, prime number, old man, and data point. These pairs pop out of the text at us, and when they belong to the same phrase they can lubricate the parsing process, allowing the words to be joined up quickly. But when they coincidentally find themselves rubbing shoulders despite belonging to different phrases, the reader will be derailed. That’s what makes the garden paths in the textbook examples so seductive, together with my real-word example that begins with the words The data point.

The textbook examples also stack the deck by taking advantage of a second way in which readers go with statistical patterns in the English language: when faced with an ambiguous word, readers favor the more frequent sense. The textbook garden paths trip up the reader because they contain ambiguous words in which the less frequent sense is the correct one: race in the transitive version of race the horse (rather than the intransitive the horse raced), fat as a noun rather than as an adjective, number as a verb rather than a noun, and so on. This can lead to garden paths in real life, too. Consider the sentence So there I stood, still as a glazed dog. I stumbled when I first read it, thinking that the writer continued to be a glazed dog (the frequent sense of still as an adverb), rather than that he was as motionless as a glazed dog (the infrequent sense of still as an adjective).

Structural parallelism. A bare syntactic tree, minus the words at the tips of its branches, lingers in memory for a few seconds after the words are gone, and during that time it is available as a template for the reader to use in parsing the next phrase.31 If the new phrase has the same structure as the preceding one, its words can be slotted into the waiting tree, and the reader will absorb it effortlessly. The pattern is called structural parallelism, and it is one of the oldest tricks in the book for elegant (and often stirring) prose:

|

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside the still waters. |

|

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. |

|

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. . . . I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. |