The attempt to restructure the government of Afghanistan is arguably one of the more ambitious efforts of the governance agenda, a Western effort to change the way other countries are governed. Over the last twenty years, both the development and the security communities have focused with increasing intensity on changing the way poor governments govern. The development community sees government as playing an essential role in fostering economic growth, contributing to individual well-being, and lifting the poor out of poverty. The security community sees government as necessary to address problems that threaten to expand beyond national borders, such as conflict, terrorism, drugs and arms trafficking, and pandemic diseases. The government that is seen as necessary to accomplish these goals is a constitutional democracy with universal adult franchise, operating under the rule of law, managing government resources, using government authority effectively for the public good, respecting and guaranteeing human rights, facilitating economic activity, helping to ensure economic growth, and providing public goods and services impersonally to citizens, such as personal security, justice, health and education services, and infrastructure.

There is debate among and within rich liberal democracies about how to implement this vision and substantial variation among rich liberal democracies, particularly about which human rights to protect, how to protect them, which public goods and services to deliver, and how to deliver them. However, the governance ideal itself is an unchallenged common core, and all of this debate happens within its framework. There are no mainstream voices arguing that government should rule to benefit the governing rather than the governed, that democracy should be eliminated, or that government need not provide any public goods and services or should provide them only to friends of people in power.

This governance ideal is a moral vision of government. We consider such a government to be “good.” Americans have a strong investment in the governance ideal, which is central to American national identity and entwined with American religiosity.

Even though we now think of this governance ideal as timeless and universal, our ideas of good government have changed over time, often emerging from violent political struggles. As we changed our expectations of government, the basis of government legitimacy changed, and we marginalized, abandoned, and even criminalized older strategies of governance, such as patronage, repression, or the claim of a right to rule based on tradition or divine right.

The current governance ideal emerged in the twentieth century. While some of our governance ideals have ancient roots, such as democracy and the rule of law, others are not even a century old, such as an egalitarian ideal that allows all adults to participate equally in the political process and guarantees equality under the law and the expectation that government will provide a wide variety of public goods and services. This change in the functions and ideas of government was enabled by increased wealth and government revenue. But if our moral vision of government requires wealth, how are we to judge governments that are too poor to provide this type of government?

The Governance Agenda

Aid agencies, militaries, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are all engaged in promoting the governance agenda. The agenda is pursued in a number of ways: through aid projects that seek to change the way poor governments govern, advocacy efforts, declarations and covenants of international organizations, and military efforts to counter insurgents by strengthening government legitimacy. A host of overlapping constituencies work to advance one or more components of the governance ideal.

The United Nations Millennium Declaration states that democratic governance and equality are “fundamental values” that are “essential to international relations in the twenty first century.”

1 As the website of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) puts it, “democratic governance and human rights are critical components of sustainable development and lasting peace.”

2 In 2009, the United States alone spent about $2.3 billion for foreign aid to promote rule of law, human rights, democracy, and good governance abroad, including funding small NGOs in other countries to campaign in their own countries.

3 NGOs such as Amnesty International, the Carter Center, Freedom House, and the Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights campaign and work for human rights overseas. The U.S. Congress requires the State Department to produce an annual report on human rights for every country in the world, and some countries have been singled out for sanctions based on human rights concerns. The rights discussed include the right to security of person; freedom from torture; freedom of speech, association, and religion; freedom from discrimination; and the rights of democratic political participation.

Barred by its charter from interfering in politics, the World Bank has nevertheless been active in attempting to reform the governance of its members in those areas it deems to be technical rather than political. In 1994, the Bank defined “good governance” as:

epitomized by predictable, open, and enlightened policymaking (that is, transparent processes); a bureaucracy imbued with a professional ethos; an executive arm of government accountable for its actions; and a strong civil society participating in public affairs; and all behaving under the rule of law.

4

Through lending and technical services, the Bank has been engaged in supporting almost all aspects of public sector reform among its member countries, except those dealing with democratic processes and human rights. This includes strengthening public financial management, improving civil service performance, strengthening justice systems, and increasing the effectiveness of government agencies providing public services. From 2009 to 2012, the World Bank lent more for public administration, law, and justice than for any other sector, including health or education.

5 Many other international organizations and foreign aid donors are also engaged in programs designed to strengthen the public sectors of poorer countries. The public financial management component is particularly important to foreign aid donors because they seek reassurance that aid funds transferred to poorer governments will be used responsibly and effectively.

The Millennium Declaration commits the United Nations to work to strengthen the rule of law.

6 Advocates for the rule of law seek to strengthen the enforcement of laws in poor countries and the extent to which the government itself abides by and is constrained by law. Because human rights are often enshrined in law and corruption is criminalized, this concern overlaps both the human rights and anticorruption agendas. NGOs such as Transparency International and Global Integrity conduct research and advocate for measures to control corruption worldwide. In 2003, the United Nations adopted the “United Nations Convention Against Corruption,” which requires signatory governments to criminalize a broad range of acts under domestic law.

7Foreign aid donors and international organizations also support projects in poor countries designed to promote economic growth by a variety of means, including changes to laws or government economic policy, or loans to governments to permit them to construct needed infrastructure. Governments, NGOs, and international organizations focus on improving the welfare of the poor abroad by working on issues such as food security, education, health, personal security, and social safety nets. They often deliver services directly; in other cases, they work to strengthen the ability of governments to provide services. Access to education, health services, and housing are also framed as part of a bundle of social and economic human rights and are part of the human rights discussion.

Finally, the U.S. military and its partners have also focused on the issue of governance. Because an insurgency is a violent political struggle for control of government, counterinsurgency (COIN) focuses on delegitimizing insurgents and strengthening the legitimacy of government. The U.S. Counterinsurgency Manual counsels: “Success in COIN can be difficult to define, but improved governance will usually bring about marginalization of the insurgents to the point at which they are destroyed, co-opted or reduced to irrelevance in numbers and capability…. The intent of a COIN campaign is to build popular support for a government while marginalizing the insurgents; it is therefore fundamentally an

armed political competition with the insurgents.”

8 Many COIN specialists see strengthening the legitimacy of a government as equivalent to widening political participation and improving government accountability, strengthening the rule of law, reducing corruption, and improving the government’s ability to guarantee security, protect human rights, and deliver services—in other words, equivalent to advancing the broad governance agenda.

9 As the Joint Chiefs of Staff reported, “Building an effective Afghan government is an integral part of the ‘clear, hold, and build’ COIN strategy because it is the Afghan government that is ultimately responsible for protecting the population, delivering public services, and enabling economic growth.”

10These different actors focus on different aspects of the governance ideal. The World Bank, for example, because of its Articles of Agreement, does not address democracy and human rights, while the United Nations focuses strongly on human rights and the Coalition in Afghanistan includes a focus on support to the Afghan military. The actors may also disagree on what governments should do or how policies should be implemented. But this debate takes place within the common frame of reference of the governance ideal, a shared vision of a constitutional democracy under the rule of law, protecting human rights, and providing public goods and services impersonally to all citizens.

A Governance Revolution

Given the fervor with which we promote these governance values, and our assumption that they are timeless and universal, it would be easy to imagine that we ourselves always had such a government and always subscribed to these values, but our ideas of governance have evolved over time. Changing ideas about the legitimate role of government led in turn to demands for changes in the way governments govern that sometimes led to violent conflict.

CHANGING IDEAS. The Enlightenment was an intellectual revolution in Western Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as the modern nation-state was forming.

11 Urbanization gave rise to new public places where people could meet and argue about ideas in salons, clubs, Masonic lodges, and coffee houses. National identities began to trump local identities, as people were united by increased mobility, the creation of national languages, and national laws. There was an explosion of printed material, now addressed to the new national “public.”

A literate urban elite challenged the absolutism of the monarchy and the authority of the church, revived and diffused ancient Greek and Roman political ideas, embraced science and rationality, questioned the foundations of the political and social order, and argued for equality, including women’s rights, the abolition of slavery, and freedom of speech and thought. The idea that kings were divinely ordained, answerable only to God, was gradually overturned in favor of republican ideals in which the people are sovereign and delegate power to the government to be used for their own benefit. With this came an idea of a citizen’s duty not to the king, but to the nation and the public. Thinkers emphasized the idea of the natural rights of the individual, the birthright of every person, which could be secured or violated by governments, but not granted or taken away by them. Older ways in which governments claimed and held power—such as appeals to monarchical tradition or divine authority to rule—no longer sufficed; they were rejected and cast aside.

This fundamental shift in Western beliefs about the nature of government was not accomplished through drawing room debate. Britain plunged into a civil war between an increasingly assertive Parliament and the king. The war ended in 1649 when King Charles I was tried for his “wicked design totally to subvert the ancient and fundamental laws and liberties of this nation, and, in their place, to introduce an arbitrary and tyrannical government.”

12 He demanded to know by what lawful authority he had been brought to trial. “I am your king … I shall not betray my trust; I have a trust committed to me by God, by old and lawful descent; I will not betray it to answer a new and unlawful authority.”

13 He threatened them with divine vengeance. Since the House of Commons had resolved “that the people, under God, are the original of all just power,” the court claimed “the authority of the Commons of England assembled in Parliament,” found him guilty, and executed him.

14In the United States, a revolution was launched in 1776. The ideas of the Framers of the Constitution were informed by the Greek philosophers and the European Enlightenment thinkers about the purpose of government, the power of the people, and human freedoms and liberties. The themes of the natural rights of man, the sovereignty of the people, and the subordination of the government to the people echo in the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

The French Revolution began about a decade later. The first three articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, one of the fundamental documents of the revolution, reiterate these beliefs:

1. Men are born free and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be based only on public utility.

2. The aim of every political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

3. The source of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation; no body, no individual can exercise authority that does not proceed from it in plain terms.

15

CHANGING ADMINISTRATION. The new ideas about the relationship between the government and the governed and about the function and purpose of government required changes in the structure of government administration. In feudal Europe, government depended on a fluid hierarchy of personal relationships. Kings held power by maintaining personal relationships with powerful nobles. In return for their loyalty and political support, the king granted them rights to income from lands, monopolies, or government positions that could be used for personal profit. They in turn held power by maintaining similar relationships with their supporters. As central government strengthened, it became less dependent on these relationships to extend control over territory, but government positions still functioned primarily as personal rewards for some time thereafter. When pressed for cash, governments sold government positions outright.

16 “Venality,” as it was called, was a frequent desperate financing mechanism of prerevolutionary France.

17

Men sought government positions as a road to wealth. Government offices were treated by office holders as a form of personal financial investment. Those who purchased their offices did so with the expectation that they would recoup the cost and make a profit through use of that office. Officials pocketed fees, sold and traded decision-making authority, and handled procurement to their own advantage.

In Britain, until at least 1780, government offices, with their salaries and perquisites, were widely and openly thought of as private property. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,

rewards did not accord with effort or duty; promotion did not occur according to merit or seniority even in a nominal sense; the highest and most lucrative places had the fewest duties, and, often, the least

raison d’être. Indeed, the most lucrative and impressive offices frequently had no duties at all, and their holders no objective qualifications for having them. Succession to responsible office was often determined by hereditary succession to that office or by open sale.

18

However, the idea of government power as a public trust meant that the use of government authority or resources for any purpose other than public benefit was increasingly unacceptable, even as governments began to find that they could no longer bear the inefficiencies of the old system. A British newspaper in 1820 described, in tones of outrage, the emoluments of Lord Liverpool, whom historians view as a government reformer:

He is first set down as First Lord of the Treasury, at £6000 a year! … After discharging all the business of the treasury, as first lord, and pocketing the £6000 a year I find him with enough time on his hands

to be a commissioner of affairs in India, with room enough in his pocket for £1500 more every year! I have scarcely recovered my astonishment at this, when I am also informed that he has also time to discharge the duty of

a Warden of the Cinque Ports which consists, I am told, of putting £4,100 a year more in his bottomless purse! But even this is not all—he has leisure enough, by working over hours, I suppose, to be

Clerk of the Rolls in Ireland, for which he pockets £3500 a year more! … They whisper, that he neither keeps the Rolls of Ireland, nor attends to the affairs of India, nor knows anything about the Cinque Ports; and that a deputy does all his work at the Treasury for a few hundred a year which is also paid by the

country!

19

A line was drawn between public and private offices and roles.

20 Government salaries were tied to the performance of government duties, the sale of offices was abolished, and a new elite social class of professional government administrators was created.

The professionalization of government began early in Prussia; the basic model of Prussian government was established by the 1830s. Robert Neild has argued that the reason for Prussia’s early reform was the need to improve the efficiency of both revenue collection and expenditure in order to pay a standing army and ensure its military readiness.

21 France followed shortly thereafter, as Napoleon modernized after the French Revolution. Britain reformed later, drawing on administrative experiments in British India. The buying and selling of government offices and the promising of a seat in Parliament were outlawed in 1809; competitive examinations for candidates to the senior civil service were introduced in 1870; and the purchase and sale of military commissions was finally abolished in 1871.

22Perhaps because it faced no serious external military threat, reform came much later in the United States. Federal government in the United States suffered from President Andrew Jackson’s introduction of the spoils system, in which an incoming administration reallocated government jobs as patronage to its political supporters. Civil servants got their jobs through local politicians and lost them if their patron lost influence or if they ceased to provide useful political support, such as campaigning for him or paying an assessment into his campaign fund of 2 to 7 percent of their salary.

23 Federal government offices did not begin to be staffed on the basis of merit until the passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883, and implementation occurred over the following decades.

Standards in state and city government were lower. In the words of a British observer, focusing only on federal civil service reform in the United States is “as if one were looking at a painting by Pieter Bruegel and had focused on an upper corner where priests are guiding virtuous people away from a village binge and had not lowered one’s eyes to the scenes of lust and debauchery in the rest of the canvas.”

24 Political machines dominated major cities until well into the twentieth century. The most famous of these was Tammany Hall, a political organization that ruled New York City for almost a hundred years. Tammany’s “bosses” used access to government for self-enrichment; the most successful became multimillionaires by awarding government contracts to themselves, selling government influence, and collecting kickbacks and protection money from the “vice” industries, such as gambling and prostitution, that they were nominally responsible for shutting down.

25By the end of the nineteenth century, however, moral standards were changing and such practices were increasingly loudly condemned. George Washington Plunkitt, a Tammany leader made famous through the publication of his interviews with a journalist in 1905, was regarded by his interviewer as refreshingly frank and unconventional because he “dared to say publicly what others of his class whisper among themselves,” while Plunkitt himself carefully drew a distinction between making money from “honest graft” (awarding government contracts to himself and using inside knowledge of government infrastructure projects to buy land and sell it to the government at an inflated price) and “dishonest graft” (embezzlement and protection rackets).

26Patronage politics still exists in rich liberal democracies, but the sale of government offices and the pocketing of fees for government decision-making were criminalized and vilified. These older strategies of governance and technologies of government administration were labeled “corruption,” a word that has inextricable moral overtones. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “corruption” as: “impairment of integrity, virtue, or moral principle: depravity b : decay, decomposition c : inducement to wrong by improper or unlawful means (as bribery) d : a departure from the original or from what is pure or correct.”

27Modern mores can be seen in the public reaction to the attempt by Rod Blagojevich, then-governor of Illinois, to sell President Obama’s vacated Senate seat. (“I’ve got this thing and it’s [expletive] golden, and uh, uh, I’m just not giving it up for [expletive] nothing,” he famously said.)

28 Perhaps he was simply born too late. Blagojevich’s behavior invited national scorn. Salon.com published “Glengarry Rod Blagojevich,” portraying a conversation with Blagojevich as written by playwright David Mamet.

29 Blagojevich was also lampooned by “Saturday Night Live” and by

The Onion. He was the subject of a musical satire by Chicago’s “Second City” and dozens of editorial cartoons. In one cartoon, mobster Al Capone scolds Blagojevich as he signs over his soul to Satan. In another, he is likened to a Tammany Hall boss. It is not that the older administrative practices have entirely vanished in rich liberal democracies, but they are no longer acceptable.

WIDER AND DEEPER. The Enlightenment “public” did not include everyone, despite calls for greater inclusion. Political participation was limited to a minority. For decades chattel slavery continued. Pseudoscientific theories of racial inferiority lent their weight to both colonialism and the Holocaust; pseudoscientific theories of female inferiority justified the exclusion of women. In the United States, the franchise was initially limited to white men with property. Even a hundred years ago, women and American Indians did not have the legal right to vote, while African American men were excluded in practice.

Figure 2.1. John Darkow, “Al Capone Scolds Rod Blagojevich.” (Courtesy of Cagle Cartoons)

Over the course of the twentieth century, egalitarianism became better established as a value, and political participation and access to government services were expanded to all adult citizens. These changes also involved conflict. They required an end to the nobility and to discrimination on the basis of religion. In the United States, the Civil War—which still stands as the war with the most U.S. casualties—was fought about the right to own slaves. Suffragettes marched for women’s right to vote, and the Civil Rights movement ended the acceptability of racial “separate but equal” policies. These battles for equal rights are recent, scars are fresh, and they are not yet over. It was only in 2013, for example, that qualified women were given the equal right to enter combat positions in the military, and while American Indians got the right to vote in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, enforcement continues to be an issue.

30Even as the pool of political participants grew, the twentieth century saw an explosive growth in government functions throughout the industrialized world. After the Great Depression, the government stepped in to attempt to revive the economy and provide a social safety net. Social insurance functions such as caring for the poor and the sick that had previously been provided by family or religious groups (to the extent that they were provided at all) became part of the function of government. In the United States, a few of the new government activities of the twentieth century include the Social Security Act of 1965 (including the creation of Medicare and Medicaid); unemployment compensation; federal aid to public education and federal financial aid for students; and a host of new regulatory activities including protections against discrimination; labor laws such as those providing for workplace safety and restricting child labor; environmental laws and regulations including the Clear Air, Water Quality and Clean Water Restoration Acts, and the Endangered Species Act; and market-supporting laws and regulations such as antitrust, securities, and consumer protection laws. In other Western countries, the social safety net was expanded earlier and even further, including such benefits as free higher education and national public health. The establishment of equal treatment under the law as an important value and the increase in the number of services that government was to provide reinforced the need for professional government staff.

Older functions of government grew in extent, complexity, and quality. Nearly all childbirth in the United States took place at home in 1900, and nearly all of it occurred in hospitals by 1945.

31 Medical technology advanced, and hospitals offered new treatment options, including renal dialysis and open-heart surgery. Staff-patient ratios dropped in hospitals, and student-teacher ratios dropped in schools where today computers are increasingly seen as necessary learning aids.

People came to see the government as having the responsibility to ensure the well-being of citizens in a broad spectrum of areas. The “welfare state” was born. The idea that the government could intervene usefully in the national economy for good has given way to the idea that it is largely responsible for the state of the national economy and has an obligation to ensure national economic growth. What we now debate is just what basket of public goods and services government should provide. (As comedian Jon Stewart put it, “They’re really only ‘entitlements’ when they’re something other people want. When it’s something you want, they’re a hallmark of a civilized society, the foundation of a great people.”

32) Today, most Republicans and Democrats who argue about the optimal size of government and its redistributive and social insurance functions do not contemplate turning the clock back to the early 1900s before the routinization of federal income tax, before Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare, federal student loans, or unemployment benefits, much less to the 1800s before free universal primary education.

The role of government in enforcing rights also expanded, as did the list of human rights to be enforced. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, drafted shortly after World War II with strong participation from socialist countries, specifies a right to “food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond [the individual’s] control.”

33 Regarding education, it states:

Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

34

While the drafting committee was deliberately ambiguous about the corresponding duty of governments to supply these goods,

35 these articles have been used to support an argument of government duty where such a duty has not simply been assumed.

New rights are emerging all the time, with corresponding obligations for governments. Almost seventy countries have adopted legislation granting a right of access to government information,

36 a right that implies the duty and ability of the government to keep, organize, and retrieve records and to photocopy them on demand. The very wealth of rich countries is used as an argument for the development of new rights. In the United States, Jesse Jackson has argued that government-provided health care “of the highest quality” is a human right on the grounds that “we can afford health care for all our citizens.”

37 President Obama, defending legislation to extend health insurance, stated, “In the wealthiest nation on Earth, no one should go broke just because they get sick. In the United States, health care is not a privilege for the fortunate few, it is a right.”

38 The Poverty and Race Research Action Council argued for a “right to housing” because “America has the resources to guarantee” it.

39Our demands and expectations of government and the standards by which we evaluate it have changed with the idea that government should derive its power from the people and use that power for their benefit, and with democratization, with egalitarianism and equality under the law, and with an expanded idea of government responsibilities for individual and national welfare. This in turn has implications for how governments should be staffed, how government workers should be remunerated, and how they should use the authority and resources at their disposal.

In rich liberal democracies, the political debates about the principles of the Enlightenment are largely over. We are no longer discussing whether we should be ruled by a king, or whether the government should be accountable to the people, or whether classes of people should be excluded from political participation or government services—instead we are largely arguing about implementation. What were daring arguments during the Enlightenment are for us today nonnegotiable articles of faith. The conflict that followed the Enlightenment left us with absolute moral convictions about human rights, the proper nature of government, and the proper use of government power. If we feel passionately about these notions of governance perhaps it is because a price was paid in blood to replace the older strategies of government, which were rejected and condemned. We represent the winning side. We are the inheritors of the victors of the political struggles of the Enlightenment.

Like a fire that starts as a thin red line on the edge of the paper, then quickly begins to consume, these ideas that began in Western Europe are spreading, violently remaking the world. The West has used its political power and dominance in the international community to project these ideas outward, and they are not limited to Western Europe and its settler countries. When I call this ideal “Western,” it is a tribute paid to its origins, not a description of its followers. Many people around the world aspire to this governance ideal. Within the common frame is great diversity in ideas about implementation and the role of government—from maximalist socialism to minimalist libertarianism—but there is a shared understanding that the legitimacy of government is based on rule of law, democratic accountability, and the provision of public goods and services in support of the general welfare.

The United States is not the only proponent of the governance agenda, but as the world’s only superpower and an economic powerhouse its voice on the international stage is loud, whether acting alone, in coalition, or as a member of international organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Although its governance values do not always trump its self-interest, they are nonetheless real, influence American foreign policy, and politicians and civil society organizations appeal to them to mobilize American public opinion.

In broad lines these values are similar to those espoused in other rich liberal democracies like those of Western Europe, but American governance values are culturally distinct both in their content and their cultural role.

40 Shared political values are the foundation of American national identity. The United States remains more religious than Western Europe, and its governance values are intertwined with American religiosity. As a consequence, the universality of these values is largely beyond question, open compromise on these values can be domestically costly, and they give rise to a missionary impulse to remake governance abroad either because of a moral obligation to assist or on the basis of expected benefits to the United States, such as peace, prosperity, reduction of terrorism, or the creation of friendly and accommodating partners.

Both President George W. Bush (who coined the term “Axis of Evil” to refer to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea) and President Obama each pledged to support the export of democratic governance and the assurance of human rights.

41 President George W. Bush said in his second inaugural address:

We are led, by events and common sense, to one conclusion: The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.

America’s vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one. From the day of our Founding, we have proclaimed that every man and woman on this earth has rights, and dignity, and matchless value, because they bear the image of the Maker of Heaven and earth. Across the generations we have proclaimed the imperative of self-government, because no one is fit to be a master, and no one deserves to be a slave. Advancing these ideals is the mission that created our Nation. It is the honorable achievement of our fathers. Now it is the urgent requirement of our nation’s security, and the calling of our time.

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

42

Or as President Obama put it with fewer religious references in his address on the Arab Spring:

We support a set of universal rights. Those rights include free speech; the freedom of peaceful assembly; freedom of religion; equality for men and women under the rule of law; and the right to choose your own leaders—whether you live in Baghdad or Damascus; Sanaa or Tehran. And finally, we support political and economic reform in the Middle East and North Africa that can meet the legitimate aspirations of ordinary people throughout the region. Our support for these principles is not a secondary interest—today I am making it clear that it is a top priority that must be translated into concrete actions, and supported by all of the diplomatic, economic and strategic tools at our disposal.

43

While in Britain the national constitutional order was gradually articulated in a series of documents, in the United States it was the drafting and ratification of the constitutional documents that defined and founded the nation. This gives the U.S. Constitution a unique cultural place. In his presidential oath, an incoming president swears to “preserve, protect and defend” not the country, not the people, but the Constitution of the United States.

44The way in which Americans handle the Constitution has no parallel unless it can be likened to the handling of a medieval relic. In the winter of 1952 original copies of the United States Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were transferred from the Library of Congress to a specially built rotunda in the National Archives built to house the “Charters of Freedom.”

At 11 a.m., December 13, 1952, Brigadier General Stoyte O. Ross, commanding general of the Air Force Headquarters Command, formally received the documents at the Library of Congress. Twelve members of the Armed Forces Special Police carried the 6 pieces of parchment in their helium-filled glass cases, enclosed in wooden crates, down the Library steps through a line of 88 servicewomen. An armored Marine Corps personnel carrier awaited the documents. Once they had been placed on mattresses inside the vehicle, they were accompanied by a color guard, ceremonial troops, the Army Band, the Air Force Drum and Bugle Corps, two light tanks, four servicemen carrying submachine guns, and a motorcycle escort in a parade down Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues to the Archives Building. Both sides of the parade route were lined by Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine, and Air Force personnel. At 11:35 a.m. General Ross and the 12 special policemen arrived at the National Archives Building, carried the crates up the steps, and formally delivered them into the custody of Archivist of the United States Wayne Grover.

45

Figure 2.2. Transfer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the National Archives, National Archives and Records Administration, 64-NA-1–434. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

President Truman spoke at the ceremony in language replete with religious imagery:

The Constitution and the Declaration of Independence can live only as long as they are enshrined in our hearts and minds. If they are not so enshrined, they would be no better than mummies in their glass cases and they could, in time, become idols whose worship would be a grim mockery of the true faith. Only as these documents are reflected in the thoughts and acts of Americans, can they remain symbols of power that can move the world. That power, is our faith in human liberty.

46

In their hermetically sealed cases, the pages were placed in the rotunda on special platforms for public viewing. At night the platforms descended twenty feet, lowering the pages into a bomb-proof vault.

47 (I was unable to confirm whether this is still the case, as the National Archives declined to comment on its security arrangements.)

In 1995 it was discovered that the glass was deteriorating and a project was launched to create new encasements. The new encasements consist of a gold-plated titanium frame, in which the documents rest on specially made pure cellulose paper “on top of an anodized aluminum support platform that is machined to conform precisely to the irregular shape of the document.”

48 The base was cut from a block of solid aluminum alloy, with windows made of sapphire. When a page of the Constitution was unveiled in its new encasement in 2000, the Archivist of the United States remarked that “without the sacred document that contains this page, we might be living in a country dominated by tyrants or a foreign power.”

49Now, on any given day, a quiet stream of visitors files past to gaze upon the Constitution in its display in the rotunda. British author G. K. Chesterton observed that America is founded on a creed; that it is “a nation with the soul of a church.”

50 It is probably more than a coincidence that our most revered civil rights leader was also a pastor.

These strong feelings set the tone of our dialogue abroad and constrain the choices of our policymakers and our people on the ground engaging poor governments. While we are patient when we think about economic growth and understand that it takes time, because our governance ideal is equated with the universal good, and contrasted with evil and tyranny, we have little patience for incrementalism when it comes to governance.

Figure 2.3. Visitors to the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom. (Courtesy of the National Archives)

The Cost of Governance

Many interconnected factors contributed to these changes to government, the basis of government legitimacy, and technologies of government administration in the West. Two recent prominent books focus on the self-interest of elites in blocking change and the circumstances under which change can happen.

51 Francis Fukuyama has pointed to the critical role of the Christian religion and the church in the rise of the rule of law.

52 Others have considered the role of the emerging middle class and the bargains it was able to strike with government in return for the payment of taxes.

53 However, one prerequisite for this type of government is adequate government revenue.

Increased centralization of government allowed nationwide taxation, which reduced reliance on older systems of revenue raising such as feudal dues or sale of monopolies.

54 Arguably, the reimagining of government as a servant of the people and stronger popular control of the budget increased people’s willingness to pay taxes. As governments were increasingly bound by law, their promises became more reliable and they were better able to borrow. As the country became wealthier, governments raised more in taxes. When governments then spent their increased revenue wisely for the public benefit, they increased their capacity, legitimacy, and credibility, and helped foster national economic growth and innovation (or at least did not hinder it), leading to higher revenues in a virtuous circle.

55The evolution of the Western governance ideal was enabled by increased government revenue. Government revenue was needed so that central governments could control their territories directly instead of relying on a fragile and fluid network of personal relationships with local power brokers. Alternate sources of government revenue were needed to end the practice of selling government positions. Revenue was also needed to replace a system in which government positions were financial benefits in and of themselves, giving the holder a right to hunt his own pay, with a system in which government jobs came with fixed salaries. Yet more revenue was needed to ensure that those salaries were sufficient to allow rules prohibiting civil servants from engaging in any other kind of remunerated work in order to minimize conflicts of interest.

Finally, substantial government revenue was needed to create a system of government in which government provides a broad number of public goods and services impersonally to the entire adult population, including those we now think of as human rights, such as universal free primary education. Both extending the type and complexity of government services and delivering them to more people required more revenue. The Western governance ideal is expensive. The welfare state as it emerged in Western Europe is so expensive that it is not clear that even those wealthy countries can sustain it.

Revenue per capita in rich liberal democracies increased precipitously. The quality of financial recordkeeping in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe leaves a great deal to be desired, but one scholar attempted to trace the rise in government revenue per capita that accompanied Western European centralization, as evidenced by the birth of national taxation, and the subsequent establishment of popular control of government spending during the nineteenth century.

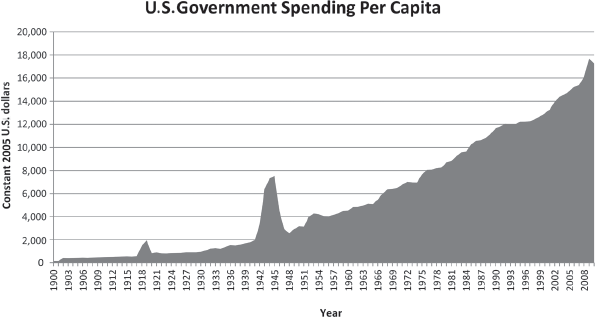

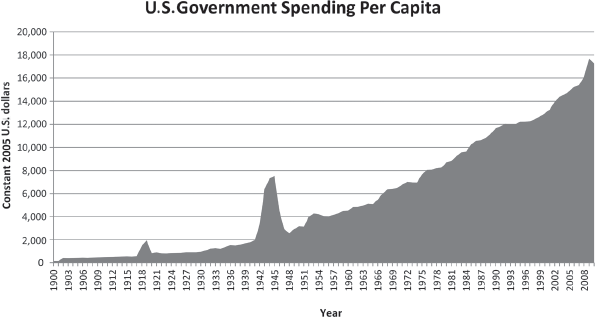

56 He estimates that French revenue per capita doubled from the 1780s to 1815, doubled again by the end of the 1860s, and doubled again by the start of World War I. Increased public sector spending prompted economist Adolph Wagner to propose Wagner’s Law in 1893—that there is a long-run tendency for the public sector to grow in relationship to the size of the economy in industrialized countries. In 1902 in the United States total government spending at all levels was about $438 per person per year in 2011 dollars; in 2013, it was $13,782.

57

Figure 2.4. U.S. Government Spending Per Capita in Constant 2005 Dollars. (Courtesy of Christopher Chantrill,

usgovernmentspending.com)

To a colleague who huffed that “it is not all about money”—that’s right, it isn’t. The historic coevolution of changing ideas and institutions, centralization, increased state capacity, better fiscal and administrative technologies, and economic growth is a soupy mess from which scholars attempt to tease out causal relationships. It may not be replicable elsewhere. But without adequate government revenue it is certainly not possible. While richer governments may not have good governance, poor governments cannot afford good governance—or in some cases any governance at all. Poor governments are too poor to provide either quantity or quality in public goods and services. While in poor countries many if not most people live in rural areas, delivery of public goods and services is concentrated in the few urban centers. Poor governments are too poor to provide rule of law, particularly when this task is complicated by the lack of a national consensus on appropriate legal rules and norms and the lack of a widely spoken national language. Because they cannot provide public goods and services to most people under the rule of law, they cannot govern by relying on the legitimacy that comes from providing them. They must use other means to hold power, relying more heavily on older, cheaper strategies of governance, such as appeals to tradition or religion, or patronage and repression. They also rely more heavily on older, cheaper technologies of government administration, such as sale of public offices or allowing government actors to monetize their positions and “pay themselves.” They do this despite the fact that they have borrowed, received, or had thrust upon them constitutions, formal government structures, and laws modeled on those of much richer Western countries that criminalize these practices, creating an extra-wide gap between law and practice.

To say that poor governments cannot afford to govern according to the Western governance ideal is not to deny the value or the rightness of those ideals. It is not an argument for cultural relativism. People would have every reason to prefer, for example, a country with a well-functioning and impartial court system when deciding where to do business, or a country that is stable, peaceful, and respectful of human rights when deciding where to travel or live. But it does mean that we should have different expectations of poor governments. We should not expect poor governments to govern like rich liberal democracies and consequently to have the same objectives, priorities, processes, or approaches to problem solving. It means that if we assume that their formal institutions and rules play the same role as similar institutions and rules are supposed to play in rich liberal democracies we will be utterly misled. It also means that our system of governance is not transferable to poor countries, and it is not clear that our current expertise in governance is very relevant to them. Finally it means that we cannot erect the Western governance ideal as the moral standard by which to judge all governments unless we simply wish to condemn the poor for not being rich.

The problem is even more serious than that. Not only do poor governments govern out of necessity with heavier reliance on disfavored strategies and administrative methods, some governments are so poor that they can’t govern their territories no matter what strategies they use. The problem of territorial consolidation and the difficulty of establishing any kind of central government remains one of their biggest challenges. In the process of the formation of the international state system, these governments were given the right and responsibility to govern their territories, but they do not have the ability. They will not have it in the short or medium term, and some may never have it. To understand how this came about, we need to first take a brief look at how they came to be considered states, and we will do so in the next chapter.