We see the governance ideal as a moral imperative. The governance of poor governments offends our democratic ideals, our belief in egalitarianism, and our belief in human rights. Our politicians routinely describe a global mission to change the way other countries govern, and this missionary impulse is a constant element in our foreign engagement. The development community has identified good governance as a development objective in itself, as well as the means to the achievement of other valued ends, such as economic growth. The security community has identified good governance as necessary for stability and the suppression of insurgencies and terrorism.

We want to believe that the governance ideal is equally available to every government and all citizens. However, poor governments do not have the resources to provide public goods and services to all their citizens, and especially not the ample basket that has come to be seen as necessary by rich liberal democracies over the last century. Many poor governments are still struggling to control the territories allocated to them during decolonization. As a consequence, they cannot govern exclusively or even primarily by means of the legitimacy that comes from providing universal public goods and services. Instead, they must continue to rely more heavily on strategies of governance we rejected. This includes buying support from elites through the distribution of government largesse (such as jobs, contracts, and monopolies), clientelism, repression, appeals to religious ideology, or cults of personality. Because they cannot provide security, a social safety net, dispute resolution, or contract enforcement services, poor governments have not displaced social mechanisms for meeting these needs, including reliance on extended family, ethnic, and patronage networks.

One attractive answer to this dilemma is to seek to “fix” poor governments so that they can govern according to the governance ideal. If we could fix them in short order, we wouldn’t need to adapt to or accommodate them, or even know very much about how they govern, except to note that it is unsatisfactory. Much of our effort with respect to poor governments has been directed to this end. The results of these efforts have been disappointing, however.

Alternately, if poor governments can’t do it, perhaps rich liberal democracies might consider taking on responsibility for assuring the quality of governance where poor governments fall short. But this is an even more ambitious idea than the idea that we can fix poor governments. We are not willing, and even if willing, would not be able.

Some have suggested that if wealth is a prerequisite of better governance, then we should put the issue of governance aside and focus instead on catalyzing economic growth in poor countries. However, waiting for growth is not a short-term solution either.

Instead we need to admit that the governance ideal is not universally available, that poor governments must govern using a different mix of strategies, and that they will continue to do so for at least the medium term and certainly as long as they are poor. We need to develop effective foreign policies to engage them given how they govern. But this admission and the compromises that it entails are so difficult that we cannot bring ourselves to make them.

Can We Fix Them?

The West has taken a number of different approaches to improving governance in poor countries. If we could fix poor governments, we wouldn’t need to adapt to or accommodate their governance in foreign policy. Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes.

Several approaches to improving governance focus on replacing government leaders, reforming government institutions, or incentivizing poor governments to govern according to the governance ideal. All of these approaches assume that poor governments can change the way they hold power if government actors simply change the way they behave.

REPLACEMENT. The corruption, weak rule of law, repression, and informality of poor governments is often attributed to a lack of “political will” for corrective action on the part of government leadership. If the leaders in charge are the problem, replacement with more energetic leaders, whether by means of elections or through force, looks like a quick and simple solution. Foreign aid donors have supported regime change through democratic elections, providing support to civil society organizations that monitor elections and journalists, as well as to opposition political parties. Decapitation of the government by force has proved to be a particularly attractive strategy for the United States given its military might. The United States has used its military power to help replace leaders or governments in countries such as Panama, Grenada, Haiti, Afghanistan, Iraq, and, most recently, Libya.

To be sure, a new leader or government can be better than an old one for any number of reasons. There are better and worse poor governments. A new leader could be more knowledgeable, more intelligent, wiser, have more “political will” to make change, more vision, better values, more respect for human rights, a better work ethic, or better relationships with domestic or foreign constituencies. But replacement in itself could be expected to change the way in which the government holds power only if all the other conditions necessary to achieve the governance ideal are present. If only the problems of poor governments and countries were that simple.

The United States has persistently intervened in Haiti, for example, but no one would say that Haiti epitomizes the governance ideal. Among other interventions, the United States occupied Haiti from 1915 until 1934; forced President Jean-Claude Duvalier to leave in 1986; suspended aid, blocked, and embargoed Haiti; and finally invaded Haiti in 1994 to restore President Aristide after he was deposed by a military regime. The invasion was justified to the American people as a limited operation that was not intended as a nation-building exercise, but rather a response to the human rights abuses of the military regime and an effort to restore democracy. The State Department issued a report that stated that “the de facto government promotes general repression and official terrorism. It sanctions the widespread use of assassination, killing, torture, beating, mutilation, rape, and other violent abuse of innocent civilians, including the most vulnerable, such as orphans.”

1 “The criteria would be the removal of the illegal Government, the restoration of civil law and giving the Haitian people an opportunity to have the kind of freely elected Government that they chose in 1990,” Secretary of State Warren Christopher told reporters. “That’s the fundamental issue.”

2Even when leaders are replaced, the new leaders of poor governments face the same territorial and political challenges and the same limited domestic resources with which to meet them. As one analysis noted in 2006, regarding the ineffectiveness of Aristide’s presidency, “Haiti has been virtually ungovernable. There was no functioning Parliament or judiciary system, no political compromise or consensus, and extreme violence perpetrated by paramilitaries, gangs, and criminal organizations. Corruption and drug trafficking ran rampant. No government enjoyed much legitimacy.”

3 Aristide ultimately accepted exile in 2004 in the face of armed revolt.

4All of this was of course before the devastating 2010 earthquake that destroyed almost all of Haiti’s public buildings, including the Presidential Palace, the parliament building, the tax headquarters, the prison, schools, and hospitals, and killed many of the government workers who were working in them at the time.

5 Although earthquakes can happen anywhere, poor countries are more vulnerable to shocks. One reason for the massive destruction and the high casualty rate was that buildings were not built to withstand earthquakes.

New leaders must build political support for the government among the same small group of elites, leveraging their ability to deliver the support of their constituencies. They face the same set of demands and pressures for redistribution from both political allies and their own family and clients. As a consequence, they must often incorporate the old elites into new patronage positions by folding them into the new government.

It should be no surprise then that the most recent elections in Haiti did not bring a fundamental change in the way in which Haiti is governed. In 2013, Freedom House noted “endemic corruption” under President Martelly, who is himself accused of accepting kickbacks and mismanaging public funds.

6 In addition, “Martelly has appointed a number of individuals to political office who have been credibly accused of human rights abuses, including Jean Morose Villiena, who was appointed mayor of Les Irois despite his facing arson, murder, and attempted murder charges.”

7 Freedom House went on to note “the absence of a viable judicial system and widespread insecurity” and violence against and intimidation of the media and human rights activists.

Similarly, in Afghanistan, President Karzai needed to build support among existing Afghan elites. A report by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff explained,

President Karzai needed to reconcile the local powerbase to GIRoA [the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan] and did so by placing warlords in key government positions as a way to obtain loyalty. Numerous political deals allowed Karzai to gain the interim presidency in 2004 and subsequently the presidency in 2009. The 25 GIRoA ministries also served as opportunities to dispense patronage through appointments…. Once ensconced within ministries and other government posts, the warlords-cum-ministers often used their positions to divert GIRoA resources to their constituencies…. Due to the extent of CPNS [criminal patronage networks], the removal of one corrupt official typically only resulted in another member of the network taking his place and continuing his corrupt practices. Despite this, president Karzai remained politically dependent on the CPNs; he therefore resisted COMISAF [Commander, International Security Assistance Force] pressure to prosecute corrupt CPN members because, as one senior civilian advisor noted, “[prosecution] meant Karzai would be putting one of his allies in jail.”

8

Instead of replacing government leaders, a more modest people-centered approach has been to seek to identify, support, and engage like-minded partners within poor governments. Foreign aid donors often seek to partner with “champions,” individual government actors, ministries, or local governments that share their commitment to the governance ideal. Engaging champions allows donors to meet their immediate institutional need to accomplish projects and missions with the help of partners with whom they are comfortable. It also has the benefit of providing some time-bound protection and benefits for donor-chosen champions. However, this type of engagement is also often presented as a poorly articulated theory of change, involving the construction of “islands” of excellence, integrity, or productivity that will somehow expand or replicate. Implicitly, this approach also assumes that the failure of poor governments to govern according to the governance ideal is a problem of lack of leadership.

This more modest approach to change has not been successful either. Although even in poor governments there are both individuals and government units that embrace the values of the governance ideal, do not monetize their government authority, and work diligently in the public interest, they are outliers operating in and constrained by a broader context. Donors overestimate the power of their champions. Sometimes they are utterly mistaken in their choice of champions. Just as replacing government leaders cannot lead poor governments to govern according to the governance ideal, neither can protecting, financing, or promoting less powerful government actors.

REFORM THE INSTITUTIONS. Another approach focuses on strengthening the capacity of poor governments by providing training, equipment, or infrastructure. Capacity-building is often combined with attempts to change the incentives of government actors by changing laws, procedures, or the organizational structure, or creating or abolishing government organizations, usually to bring them in tighter conformity with those of rich liberal democracies. Rather than replace government leadership, both seek to change the behavior of government actors. On its face, this looks as if reform could be accomplished relatively speedily, even if more slowly than simply replacing offending government officials.

While foreign aid donors promote the governance ideal through capacity building and institutional reform as a development goal in itself, or as a means of supporting economic growth or reducing poverty, the U.S. military sees such reforms as critical to fighting insurgents. The purpose of a counterinsurgency (COIN) campaign, according to the U.S. Counterinsurgency Field Manual, is to “foster development of effective governance by a legitimate government” where “governments described as ‘legitimate’ rule primarily with the consent of the governed; those described as ‘illegitimate’ tend to rely mainly or entirely on coercion.”

9 To accomplish this, “soldiers and Marines are expected to be nation builders as well as warriors. They must be prepared to help reestablish institutions and local security forces and assist in rebuilding infrastructure and basic services. They must be able to facilitate establishing local governance and the rule of law.”

10 Implicit in this statement is the idea that, at one time, institutions were functioning, infrastructure existed, the government delivered basic services, and the rule of law existed. Insurgencies arise as a consequence of dissatisfaction with the government because of its failure to govern according to the governance ideal. The U.S. Government Counterinsurgency Guide states that a condition of a successful COIN operation is that

the affected government is seen as legitimate, controlling social, political, economic and security institutions that meet the population’s needs, including adequate mechanisms to address the grievances that may have fueled support of the insurgency…. Almost by definition, a government facing insurgency will require a degree of political “behavior modification” (substantive political reform, anti-corruption and governance improvement) in order to successfully address the grievances that gave rise to insurgency in the first place.

11

There may be value in institutional reform, and foreign aid donors have often succeeded in persuading poor governments to change their formal institutions and laws. However, there is no evidence that transferring the formal institutions of rich liberal democracies to poor governments will make poor governments govern like rich liberal democracies. Where rule of law is weak, laws and official procedures are not effective instruments for driving behavioral change.

Indeed, the institutional transfer project is likely based on too simple an idea of causality. Formal institutions may indeed constrain and shape behavior, but deeper patterns of social behavior shape and uphold formal institutions. As Vivek Sharma put it in his essay, “Give Corruption a Chance,”

the outcomes produced by Denmark are not merely the function of possessing good administrative institutions; rather, they are instead a consequence of the emergence of particular configurations of authority that are deeply rooted in the society. The “efficient” and “fair” functioning of Denmark’s administrative institutions is a consequence of the fact that these administrative organs are staffed by Danes who take for granted certain patterns of authority in general. Danes did not become prosperous because of the Danish state: they became prosperous because of the way in which they organized their lives in general. The Danish state is a reflection and a consequence of this deeper change in the way in which Danish social organization evolved. Simply taking Danish-style administrative organs and transplanting them to Afghanistan cannot work because the people who would actually staff them would be Afghans, and Afghan institutions are infused with a different category of authority.

12

Since the beginning of development work in law and governance, scholars and practitioners have cautioned against the “sympathetic magic” practice of exporting Western institutions and laws to poor countries and expecting them to operate the same way or even to operate at all. Allot spoke of “phantom legislation” in Africa in 1968—laws on the books that were simply not enforced or implemented.

13 Economists Acemoglu and Robinson have offered similar cautions about institutional transfer.

14 Harvard public administration specialist Matt Andrews has warned against reforms that “produce new laws, systems, and processes that make governments look better” but go unimplemented.

15 Regarding its efforts at civil service reform, the World Bank’s evaluation group noted,

in countries where the patronage system is prevalent, reforms that affect pay, recruitment, and promotion are very difficult to achieve…. Diagnoses have concluded that the patronage system in developing countries creates a very difficult reform environment. It is important to be realistic that a country’s system will not change overnight and that focusing on select entry points and incrementalism will be more successful than any attempt at remodeling an entire system.

16

INCENTIVIZE THEM TO GOVERN. Another approach is to admit that we don’t know how to improve poor governments and instead to incentivize them to deliver the type of governance that we want. This approach also assumes that changing the way poor governments hold power is simply a matter of changing the behavior of government actors.

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is a U.S. foreign aid agency that awards grants of hundreds of millions of dollars to governments that perform well on a number of indicators that seek to measure the success of the government in Ruling Justly, Investing in People, and Encouraging Economic Freedom.

17 This selective approach is supposed to ensure that aid money is used well by recipients and to incentivize those that do not qualify for compacts to change the way they govern. Under current legislation, the MCC must also exclude from consideration countries whose governance is considered very bad—although presumably these are exactly the governments that would benefit most from being incentivized to improve. Excluded countries include those in which an elected head of government was deposed by coup (Sudan, Madagascar, Mali, and Guinea-Bissau), those lacking rule of law (Zimbabwe), those lacking fiscal transparency (Cameroon, Central African Republic, The Gambia, Madagascar, Nicaragua, and Swaziland), those supporting international terrorism (Sudan, Syria, North Korea), or those in arrears in debt owed to the United States (Syria, Sudan).

18The MCC divides eligible countries into low-income and lower-middle-income categories. Countries are evaluated against other countries in their income group. However, it uses the same criteria to evaluate the governance of all countries regardless of their wealth, implicitly assuming that all governments can and should govern the same way. The indicators include measures of the rule of law, the control of corruption, immunization rates, and public expenditure on health and education—all measures of the ability of the government to govern by providing universal public goods and services under the rule of law.

Reflecting the belief in the universal achievability of the governance ideal, countries that are not precluded from receiving U.S. aid and do not qualify for MCC grants are considered for the Threshold Program, a USAID program that aims to produce quantifiable improvements in governance within two years by providing funding and expert assistance. However, a review of this program concluded that “using a country threshold program to improve performance on MCC’s eligibility indicators within a narrow time frame, however, has not been effective in most cases.”

19Replacement of government leaders, engagement with “champions,” reform of government institutions, and incentivizing government actors as ways of achieving the governance ideal are premised on the idea that all governments can govern according to that ideal and that the only constraint is the capacity and bad behavior of government actors. These approaches may be valuable and effective for advancing more limited goals or even worthwhile as prerequisite steps that might set the stage for subsequent change, but there is not a single case in which these approaches have enabled a poor government to abandon reliance on other governance strategies and to govern according to the governance ideal. It does not matter whether we bomb them, invade them, teach them, praise them, reform them, incentivize them, or sanction them. Poor governments cannot govern according to the governance ideal as long as they are poor.

Can We Do It Ourselves?

The creation of the modern state system was accomplished by divorcing the right to govern from the ability to govern. The expectation was that statehood in fact would follow statehood in law; that governments would “grow into” their territories and responsibilities. However, declaring statehood did not assure the governance of the territories of poor countries. The president of Somaliland implicitly tagged the problem with the modern state system when he said, “You can’t be donated power.”

20If poor governments can’t govern according to the governance ideal by themselves, one possibility might be for rich liberal democracies to assume responsibility either for governing or for helping poor governments to govern. The responsibilities of poor governments could be reduced to match their capacities by reducing their territorial or functional responsibilities. We would then need to fill the governance vacuum. However, we are not willing to take on these responsibilities, and even if we were willing, we could not fulfill them.

REVISIT THE STATE SYSTEM. Poor governments enjoy the legal rights of governments of states whether or not they are able to carry out the responsibilities of governance. International law usually requires other governments to deal with the recognized government regarding all matters within the state’s borders. Although poor governments may not themselves be able to govern their territories, they have the legal authority to prevent others from reaching populations at risk or pursuing criminals or terrorists within their borders, or to set any conditions on access—such as exacting payment for the privilege of delivering aid. This is part of the continuing frustration of the disenfranchised who live in these territories. Although they receive little or no government services, they may not be able to emigrate to richer countries, erect their own governments, or negotiate directly with foreign actors to receive assistance, and other national governments do not have any obligation to them and are not accountable to them.

One possible solution to the puzzle of governance in poor countries is to abandon legal fictions of statehood and realign rights, abilities, and responsibilities. A government’s claims to a territory would be recognized only if it could demonstrate that it actually governed according to some minimum standard, such as delivering an adequate level of security and services to the population that lives there. One scholar has suggested that we might think about “decertifying” states.

21 We would once again draw maps that reflect power, rather than international legal claims. This would then allow a conversation about how stateless (not “ungoverned”) spaces should be governed, how the needs of the populations who live in them should be met and by whom, and how the problems that arise within them should be resolved. Because recognition of the territorial claims of poor governments would reflect their actual governance to a minimum standard, they would have every incentive to govern to that standard and, by definition, would have adequate resources to do it.

Or instead of all-or-nothing legal rights over territory, we could also imagine increasingly stronger legal rights as a government delivers more to its population, so that stateness becomes a continuum. Poor governments cannot supply even the most minimalist set of public goods and services to all their citizens. Most cannot supply personal security or justice or defend the population against criminals, terrorists, or insurgents. Rather than reducing the territory of poor governments, poor governments could have more limited obligations to supply public goods and services to a subset of the population, rather than attempting to serve so many that their meager resources are diluted to insignificance. When the government’s responsibilities are in line with its available resources and capacity, the government could then be held responsible for performance. Perhaps “quasi-states” should have “quasi-sovereignty”—but there is a real question of how a government that delivers very little can win popular support.

This would be a solution to the governance problem only if there were another entity willing and better able to fulfill those responsibilities. The relationship between that entity and the people living in the territory would have to be defined. Without a clearly defined alternative to the present state system, it is hard to say that the disenfranchised would be better off.

In any event, it is not politically feasible. Rich governments (and their citizens) have no incentive to take responsibility for resolving the problems of poor people in other countries except when they threaten to have spillover effects. Poor governments have no incentive to give up any of their territory—even if they cannot govern it—or to give up their functions—even if they cannot perform them.

GIVE THEM MONEY. Yet another alternative would be for rich liberal democracies to subsidize poor governments at a level sufficient to allow them to provide universal public goods and services, the rule of law, and to hold democratic elections. Rich liberal democracies, rather than governing the territory directly or assuming direct responsibility for service delivery, could engage in a form of indirect rule, enabling poor governments to govern as long as their governance conforms to the governance ideal.

Foreign aid donors, NGOs, and even militaries already deliver foreign aid to poor governments and often deliver public goods and services such as health and education services directly. Although foreign aid is critical to the operation of poor governments—on average in 2010, for those from which we have data, foreign aid was half of all government expenditure

22—the combined efforts of poor governments and foreign actors still fall far short of ensuring that poor country citizens receive basic security, rule of law, and universal public goods and services. It is unclear how much aid would be required to overcome the fiscal constraint to the governance ideal, but it is fair to say that it would be substantially more than donors are currently giving and likely more than they can give. Aid remains volatile, provided by a shifting set of uncoordinated volunteers with their own agendas. They are not accountable to anyone if they fail to deliver on their promises, least of all to aid beneficiaries. Donors tax the limited capacity of poor governments in their demands for reports and interaction, as where by the end of the 1990s, the government of Tanzania was famously made to write more than 2,400 quarterly donor reports and host more than 1,000 donor missions annually.

23 Donors repeatedly promise to coordinate and harmonize their demands so that they are less burdensome to recipients, but their own institutional incentives make it difficult for them to do so.

We are also reluctant to accept responsibility for subsidizing poor governments. Relaxing the expectation that poor governments should be self-financing would mean more than giving them aid seen as charity; it would mean assuming real responsibility for their financing. At present, most donor governments and their citizens do not feel an obligation to deliver aid even when they have pledged it. In economic downturns, donors cut their aid budgets—just when poor governments need the money.

24Popular support for foreign aid in the United States is already tenuous. The United States, while not the world’s richest country, is one of the world’s largest economies and is by far the largest donor of bilateral aid. But many Americans would not eagerly agree to subsidize poor governments indefinitely. They are willing to help the “deserving poor”—those who are impoverished through no fault of their own. However, many believe that hard work and prudence overcome poverty and so tend to find persistent poverty suspect. They worry that someone who is poor for too long is attempting to take advantage of the hard work of others.

Where the aid recipient government is seen to be morally suspect—engaged, for example, in corruption or repression as most poor governments are—there would be very little popular support for subsidizing that government. Foreign aid has been described by conservatives as “pouring money down a rathole.” As Douglas Casey quipped, “Foreign aid might be defined as a transfer of money from poor people in rich countries to rich people in poor countries.”

25 An editorial in the

Wall Street Journal titled “To Help Haiti, End Foreign Aid” argued:

Mr. Shikwati and others like Kenya’s John Githongo and Zambia’s Dambisa Moyo have had the benefit of seeing first hand how the aid industry wrecked their countries. That the industry typically does so in connivance with the same local governments that have led their people to ruin only serves to help keep those elites in power, perpetuating the toxic circle of dependence and misrule that’s been the bane of countries like Haiti for generations.

26

Polls show that Americans do not know how much money is spent in foreign aid, and also think that too much money is dedicated to foreign aid, although the definition of foreign aid that is used by both pollsters and respondents is often unclear. For example, a 2013 poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 61 percent of those surveyed felt that the U.S. spent too much on foreign aid, which for many included military assistance.

27 (The United Kingdom is the second largest bilateral donor, and its citizens are also skeptical of foreign aid. A national poll found that 60 percent believe that foreign aid is wasted.

28)

Finally, even if we were willing to assume responsibility for subsidizing poor governments as needed, this alone would be unlikely to change the way poor governments hold power; the revenue constraint is only one of many. A fundamental shift in the relations of power is not so easily accomplished. To quote Frederick Douglass, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

29 The persistence of patronage and authoritarian governance in wealthier countries demonstrates that while adequate revenue is necessary for good governance, it is not sufficient. Just as there is no automatic adoption of the governance ideal with economic growth, neither is there an automatic adoption as the result of foreign aid. The governance ideal was advanced in the West through conflict and struggle.

A substantial increase in foreign aid might even have the reverse effect. Because poor governments have weak administrations, they cannot rationally spend (much less track or audit) large aid flows, creating waste and new opportunities for capture. Pouring massive amounts of money into poor governments is like trying to fill a teacup with a fire hose—water will go everywhere. In Afghanistan, which not only received military assistance and foreign aid, but also the money that was used by the Coalition for local procurement, the influx of dollars swamped not only the Afghan government but also the Afghan economy.

30 According to one expert, Afghanistan was saturated with inflows within the first year of operations. Not only was the Afghan government unable to track the funds, the U.S. government was also unable to track them.

Increasing aid flows to a poor government may simply result in a class of fabulously wealthy elites, cementing the existing patronage system, or it may allow a strengthening of the security apparatus to be used for repression; in neither case does it advance good governance. We have seen examples of this dynamic in poor governments that received revenue windfalls in the form of oil money to the point that there is a literature about how poor governments can manage the “oil curse.”

31 Some scholars believe that the key to good governance is a relationship in which the government is accountable to the people because it depends on them for tax revenue.

32 Financing governments from the outside weakens this link.

Aid skeptics argue that aid is doing more harm than good. Kenyan economist James Shikwati said about development aid for Africa, “For God’s sake, please just stop.” He went on to explain:

Huge bureaucracies are financed (with the aid money), corruption and complacency are promoted, Africans are taught to be beggars and not to be independent. In addition, development aid weakens the local markets everywhere and dampens the spirit of entrepreneurship that we so desperately need. As absurd as it may sound: Development aid is one of the reasons for Africa’s problems. If the West were to cancel these payments, normal Africans wouldn’t even notice. Only the functionaries would be hard hit. Which is why they maintain that the world would stop turning without this development aid.

33

It is not clear whether delivering larger volumes of aid indefinitely to poor governments would solve their governance problems or just exacerbate them.

Make Them Rich?

Yet another approach to attaining the governance ideal in poor countries might be to wait for or to help catalyze economic growth.

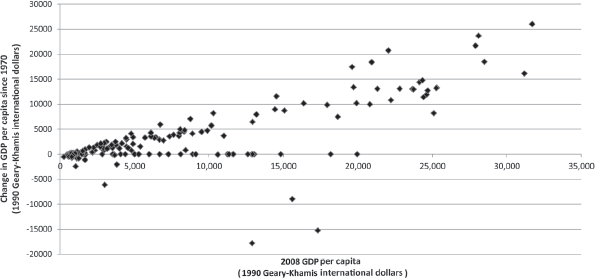

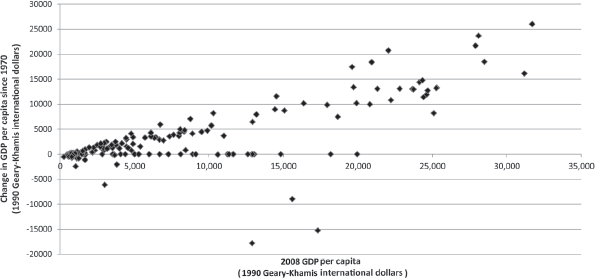

Figure 8.1 shows changes in GDP per capita between 1970 and 2008 for 163 countries.

34 A number of countries have been mired in poverty for decades; some were poor dependencies before they became poor countries. If national wealth is a prerequisite of good governance, whether because it increases government revenue or through some other channel, then perhaps we should focus less on making poor governments govern like rich governments and focus more on making them into rich governments.

Figure 8.1. GDP Per Capita Between 1970 and 2008 for 163 Countries in 1990 International Geary-Khamis Dollars. (Data from Angus Maddison,

Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1–2008 AD,

www.ggdc.net/maddison/oriindex.htm)

However, if the answer to achieving the governance ideal is economic growth, we have a few problems. The first is that we do not know how to ensure economic growth. The question of how nations become wealthy was posed by Adam Smith in 1776, and while it has spawned a field of study in economics, there is nothing close to a consensus with respect to the answer. The rapid economic rise of the “East Asian tigers”—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—was called a “miracle” because such growth stories were historically unprecedented and flouted all of the dominant theories for how national economic growth was accomplished. China is playing that contrarian role today, defying conventional economic thinking, and yet its gross national income per capita has grown at 10 percent per year on average between 1979 and 2011.

35 (By contrast, the rate in high-income countries over the same period was almost 2 percent per year.) Because we do not know what stimulates economic growth—consider the debates about the response to the recent U.S. recession—we are also unable to say with any precision what government policies poor countries should adopt to ensure economic growth, much less how to get poor governments to adopt and implement them. The answers will not be the same for all countries at all times.

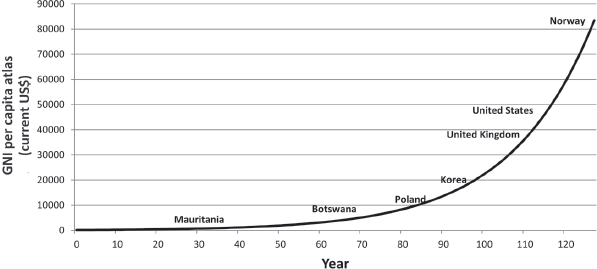

In any event, waiting for economic growth in poor countries is likely to be, at best, a medium-term solution to the governance problem. This is because, notwithstanding a handful of outstanding growth stories like those of Singapore and South Korea, most economic growth happens more slowly, and the gap between rich and poor countries is very large. If the gross national income per capita of one of the world’s poorest countries, Burundi, were to grow at a respectable 5 percent every year, Burundi would catch up with where Mauritania is today in thirty years and where Botswana is today in about seventy.

Figure 8.2. How Long Would It Take Burundi to Be as Rich as Norway Is Right Now, if It Grew at 5% GNI Per Capita?

Finally, although wealth may be necessary for the governance ideal, it is by no means sufficient. There is a lively debate in both the academic and policy literature about whether better governance causes economic development or the other way around. Both points of view are likely too simple. In rich liberal democracies, increased wealth and gradual changes to governance were mutually reinforcing over centuries. As countries grew richer, their governments had more revenue and more possibilities for implementing policies, and their wealthier and better-educated populations became more demanding. Some countries have grown richer without making a shift to liberal democracy. In some middle-income countries, such as those in the Middle East and North Africa, and oil-rich countries like Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, governments continue to rely heavily on patronage and repression to govern. Recent work in economic theory rejects the idea that countries necessarily progress along a single path toward the governance ideal as they get richer.

36There may be many reasons to replace a government leader, reform a government institution, incentivize a poor government, provide foreign aid, or attempt to catalyze economic growth in a poor country. These approaches may even allow some incremental improvement in governance. What they can’t do is bring about a rapid shift in how poor governments hold power. They do not allow us to avoid the uncomfortable discussion about how poor governments govern and what this implies for how we must engage them effectively and ethically.

Dealing with Poor Governments

If we cannot “fix” poor governments, and if their strategies of governance are likely to persist for some time, then we must, for the interim, decide how we want to respond to the way they govern. It is tempting to deny, to continue to engage poor governments as if they were simply poorer rich liberal democracies, as if the laws and formal institutional structures of government defined how they operated and as if their interest lay solely in public service delivery, rule of law, and democratic accountability. But as tempting as it is to live in an easier alternate universe, this approach has led us to misunderstand the intentions, actions, and capacities of poor governments, to make investments that are unlikely to bear fruit, to sacrifice lives needlessly, and perhaps even to destabilize poor governments.

GO AROUND. One way to deal with poor governments is to disengage, go around them, and ignore them, at the risk of violating their sovereignty. Foreign aid donors have historically gone around poor governments by “ringfencing” aid projects. Projects are said to be “ringfenced” when donors run aid projects themselves or work with the government to set up stand-alone project implementation units with dedicated government staff. Donors may ringfence projects when they have concerns about the government’s capacity or willingness to run an aid project, and in particular, when they are concerned that the government would divert project resources and pose a fiduciary risk (although, for diplomatic reasons, such concerns are rarely voiced publicly).

Ringfencing came under increasing criticism as the number of donors and projects multiplied, creating thousands of uncoordinated, overlapping, and conflicting projects over which the recipient government had little control and often little information. Given that, for poor governments, foreign aid can be the equivalent of the government’s own revenues or more, this meant that a substantial percentage of public funds were out of the control of the government. It was argued that the government’s ability to make public policy was undermined. In addition, because donor projects offered good salaries, working environments, and professional opportunities, they created a “brain drain” from the recipient government to donor projects and project implementation units, weakening government human resource capacity. Where donors delivered project services directly, some argued that the effect was to marginalize the government in the eyes of the public and undermine the government’s legitimacy. Finally, although ringfencing was done in large part to guard against misuse of donor funds, it was not clear that donors were able to monitor their projects adequately to prevent such misuses, even when projects were ringfenced.

For all of these reasons, there have been strong calls to abandon ringfencing and move to direct budget support. Direct budget support is based on the assumption that donors and poor governments have the same kind of governance and priorities, use similar processes and institutions to accomplish similar goals, and that any differences on the ground are attributable to lack of training and capacity. Under direct budget support, instead of financing projects, donors provide financing directly to the government to be managed through the government’s own policymaking, budgeting, and public expenditure systems. Direct budget support is accompanied by donor technical assistance designed to help strengthen the capacity of the government to make and implement policy and to manage public funds.

At the end of the day, despite repeated calls to turn to direct budget support, direct budget support comprises less than 3 percent of government development assistance.

37 In part, this reflects donors’ need to get individual credit for their projects, whether to gain international reputation and “soft power” or to demonstrate their own institutional effectiveness to a domestic audience. But it is also the case that most donors don’t want to relinquish that amount of control, take on that degree of fiduciary risk, and be left to explain to domestic taxpayers how, for example, the aid money that was given to Afghanistan found its way to Kuwait. Donors know, but cannot say out loud, that poor governments do not govern the same way rich liberal democracies do, and they do not have the same priorities. Foreign aid in poor countries continues to “go around” the government.

MEET THEM WHERE THEY ARE. Alternately, we could engage poor governments directly, acknowledging and adapting to their governance strategies. This involves identifying and bargaining with the relevant actors with influence and decision-making authority, regardless of their formal positions. In patronage systems, it may involve acting as a patron and recruiting poor government elites as clients, thereby leveraging their client networks. For example, historian Mark Moyar argued that a COIN approach in Afghanistan that focuses on big development projects that aim to confer broad social and political benefits on the population is unlikely to succeed.

38 This “population-centered” COIN fails both to address the population’s principal concerns and to engage the elites that drive public action and opinion. Instead, he argues for targeting spending to elites and allowing them to direct that money to their client networks:

Channeling aid to elites and demanding their support in return was instrumental to the counterinsurgency triumph in Iraq. During the first few years of the Iraq War, U.S. policymakers forbade this method in the interest of building up a democratic national government and national security forces, a policy that caused large numbers of Iraqi elites to side with the insurgents and did little to bring other elites to the counterinsurgent side….

The insurgency eventually became so bad that the prohibition against cutting deals with local elites was lifted, at which point American commanders quickly co-opted tribal leaders by paying them $35,000 for a $25,000 school and letting them dole out construction contracts to their kinsmen. At American insistence, these Iraqi elites returned the favor by providing intelligence information or recruiting men into local security forces. If the tribal leaders dragged their feet on taking action against the insurgents, the United States could threaten them with a withdrawal of aid, and such threats often achieved the intended effect.

39

The Central Intelligence Agency has been using a similar strategy in Afghanistan. It began supporting Hamid Karzai as an ally against al Qaeda and continued to drop off bags of cash at his office when he was president. The payments “totaled tens of millions of dollars since they began a decade ago,” according to Afghan officials.

40 With candor and perhaps a bit of puzzlement as to why this had become an issue, Karzai explained that the presidential slush fund “helped pay rent for various officials, treat wounded members of his presidential guard and even pay for scholarships.”

The New York Times explained:

But it was Mr. Karzai’s acknowledgment that some of the money had been given to “political elites” that was most likely to intensify concerns about the cash and how it is used.

In Afghanistan, the political elite includes many men more commonly described as warlords, people with ties to the opium trade and to organized crime, along with lawmakers and other senior officials. Many were the subjects of American-led investigations that yielded reams of intelligence and evidence but almost no significant prosecutions by the Afghan authorities.

“Yes, sometimes Afghanistan’s political elites have some needs, they have requested our help and we have helped them,” Mr. Karzai said. “But we have not spent it to strengthen a particular political movement. It’s not like that. It has been given to individuals.”

41

Afghan, American, and European officials objected that the CIA’s cash deliveries “effectively undercut a pillar of the American war strategy: the building of a clean and credible Afghan government to wean popular support from the Taliban.”

42A third example of this type of engagement is a cautionary tale about the dangers of engaging poor governments on their own terms. The risk is that such engagement could change who we are and challenge some of the victories we have won in our own domestic governance arena.

Formal independence did not end France’s relationship with her former African colonies. France continued to exercise strong influence in the selection of government leaders, the military protection of regimes, and in trade agreements, particularly with regard to access to oil. France built and maintained long-term personal social relationships between French and African government elites. The national oil company, Elf Aquitaine, was used as a vehicle for payments to African leaders. The closeness of this relationship is captured in the term to describe it: “FrançAfrique.”

These engagements violated French law. When the details became public in 1994, it was a national scandal. The French government was widely criticized for propping up the regimes of African leaders whose governance was marked by human rights violations and corruption. The “Elf Affair” led to criminal prosecutions in what

The Guardian called “probably the biggest political and corporate sleaze scandal to hit a western democracy since the second world war.”

43

But the four-month trial, which had France riveted with its tales of political graft and sumptuous living, was also that of a system of state-sanctioned sleaze that flourished in France for years: successive politicians saw the country’s state-owned multinationals not just as undercover foreign policy tools, but as a convenient source of ready cash to keep friends happy and enemies quiet.

Le Floch [the former CEO of Elf Aquitaine], whose lawyer said yesterday his client would not be appealing to the court, insisted throughout his trial that he was in “daily contact” with the Elysée palace, and that “all the presidents of France” had known of, and condoned, the company’s illicit dealings….

Many of the missing millions were paid out in illegal “royalties” to various African leaders and their families.

44

But the flow of funds was not unidirectional. “Let’s call a spade a spade,” said Le Floch in 2002. “The money from Elf goes to Africa and comes back to France.”

45 In 2011, French lawyer Robert Bourgi claimed in an interview that between 1997 and 2005 he had transported millions of dollars in campaign contributions to former French president Jacques Chirac and his political ally Dominique de Villepin from Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea.

46 The convicted middlemen Tarallo and Sirven also enjoyed substantial benefits. “Much of the money was spent on jewellery, artworks and sumptuous apartments: the magnificent villa that Tarallo bought on Corsica was estimated at €23.1m, while Sirven spent €1m a year for six years on jewels alone.”

47Meeting poor governments where they are is not an easy alternative either. If a major change to the state system or a commitment to fill the gap in poor countries goes against our key interests, the abandonment of our belief in the universality of our governance ideal goes against our most deeply held values. Patronage systems offend our belief in human equality because they provide unequal access to government positions, authority, resources, and services. Patronage systems are also less effective for policy development and implementation, as the use of government offices, contracts, and powers for patronage may conflict with their use in the public interest. Governance that relies on repression or violates human rights is even more offensive to us. “What happens if we leave Afghanistan?” asked the August 9, 2010 cover of

Time Magazine. The answer was given by the photograph of eighteen-year-old Aisha, whose nose was cut off by her husband and brother-in-law on the order of a Taliban judge after she fled an abusive marriage. Implicit in the question was the idea that the presence of the United States could help protect human rights. Just that May, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had promised not to abandon the women of Afghanistan.

Advocates for the governance ideal would likely argue that complacency regarding the injustice, inequality, and repression of poor governments could suppress demand for change where change is in fact possible. If we accept from poor governments what we consider to be unacceptable in richer ones, we will have a dual standard. This is uncomfortably reminiscent of colonialism, when citizens of the metropole and colonial subjects had different legal status and were governed by different institutions, standards, and laws. It is also racially charged because colonial dualism was often justified on a racial basis and because of the racial composition of today’s rich and poor countries. Many would see acceptance of the strategies that poor governments use to govern as a statement that the lives and freedoms of people in poor countries are worth less than those of rich liberal democracies—that poor people are somehow less deserving. A dual standard might also undermine standards in rich countries by changing a “bright line” rule (“never do this, it is wrong”) to a rule that is contextual (“it’s alright under certain circumstances”), threatening governance gains at home.

Coming to Terms

Because we believe that every country can and should be governed by providing public goods and services to all citizens under the rule of law subject to the accountability of democratic elections, we use our power and our position in the world to universalize our governance values. We demand the adoption of the same formal institutions and the passage of laws that criminalize other strategies of governance. Even now, as the development community looks to set new global targets for development post-2015, after the current Millennium Development Goals expire, some are advocating the establishment of global targets for democratic governance, control of corruption, and the rule of law.

48But the governance ideal as it is expressed today is historically recent and geographically limited, and the idea that this way of holding power is available to everyone is newer still. Today’s rich liberal democracies became states because their governments gradually increased the territory under their control, often through conquest. Today’s poor governments were assigned territories and then expected to build a state out to arbitrarily assigned borders. Today’s rich liberal democracies relied on cheaper strategies of governance when they were poor, such as appeals to tradition, patronage, religious ideology, and repression. Poor governments are expected to govern their territories without recourse to such strategies. Rich liberal democracies supplied a much more limited basket of public goods and services when they were poor and to a more limited group of people—even a hundred years ago. Poor governments are expected to supply the same basket as today’s rich governments do and to everyone. Governments of today’s rich liberal democracies were built through centuries of economic growth and gradual government expansion, even as power concentrated among elites was eventually extended to the adult population through political and armed struggle. Poor governments are expected to start with full franchise democracy and deliver the same governance without any intermediate steps and to work this transformation by a graceful consensus in which those who would lose would volunteer to be losers. Finally, poor governments are asked to govern subject to the pressures of the international community, driven by much richer, more powerful, and impatient countries with strong preferences about the way they govern.

There are doubtless many prerequisites for the governance ideal. Scholars and practitioners seeking to explain the way poor governments hold power have pointed to precolonial culture, the impact of colonization on culture, tribalism, ethnic diversity, and greedy, corrupt, exploitative, bloodthirsty, predatory, kleptocratic elites who lack “political will,” a mysterious invisible quality that can only be detected by its absence. Some see poor governments as historical throwbacks, because this type of national and governmental poverty is in the Western past. Regional scholars have attempted to understand how poor governments hold power looking only in Sub-Saharan Africa, only in Central Asia, or only in South Asia, and while this narrow focus has enabled them to see idiosyncratic qualities of particular poor governments, it leads them to overlook the common consequences of poverty.

Whether in Africa, Central Asia, or South Asia, poor governments are too poor to satisfy our expectations. Although adequate revenue is not sufficient for the governance ideal, it is absolutely necessary. While we have seen some countries grow wealthier and gradually change the way their governments hold power in tandem, there are a group of governments that are so poor that they cannot govern exclusively or primarily by winning popular support and legitimacy by providing universal public goods and services under the rule of law, subject to democratic accountability. They are too poor to provide minimal services to their entire populations, or even to establish much presence in parts of their territories. They cannot provide basic security or justice, cannot enforce contracts reliably, cannot deal effectively with challengers. They can’t even afford to pay for their own national elections. Instead, they provide services to some, buy political support from others, repress political opponents, and ignore parts of their territory and the people who live there. They invoke shared religious beliefs, shared ethnicity, a common enemy, or a common struggle. They look the other way when civil servants pay themselves, because they cannot afford to pay them.

We see these older, cheaper strategies of governance as immoral, corrupt, and evil. When we do acknowledge that poor governments govern differently, we condemn them. We intervene on the theory that stoking popular dissatisfaction and demand for change, tinkering with formal institutions, or replacing government leaders will result in a fundamental change in the way the government holds power without acknowledging that the governance ideal is so expensive that some simply cannot afford it. But the insistence that poor governments hold power and govern the same way that rich liberal democracies do is reminiscent of Rousseau’s anecdote about the princess who, when told that the peasants had no bread, said, “Then let them eat pastry!” To pretend that the options of the poor are the same as the options of the rich is false egalitarianism. It is an especially uncomfortable position given the role that the rich West has played in shaping today’s poor states.

Because we have labeled their governance as evil, we cannot talk openly about the constraints poor governments face, discuss beneficial incremental changes to the way the government holds power, or discuss adaptive strategies for engagement. When I want to get a laugh from my World Bank colleagues, I ask them when they are going to hold a workshop on “Patronage Best Practices.” And then, while they are laughing uncomfortably, I ask them why this is so funny. If we care about improving governance, and if poor governments are compelled to rely on strategies such as patronage to govern, this is exactly what we should be doing. But I already know why they are laughing. Such a frank admission that our governance ideals may not be universally available or any sign of accommodating the disfavored strategies of poor governments would be career suicide both for the unlucky Bank staff and the government officials who participated in the workshop. Our dialogue with poor governments depends on mutual denial.

In part our problem is ignorance, a problem of class and social distance on a global scale, a failure to understand what it means to be poor, a cultural blind spot. But our failure to learn goes much deeper than that. Accepting that not every government can govern the way we would like leads to very hard choices that involve compromising our interests or our values. Our choices are so unappealing and costly; it is easier to avoid them. This—not naïveté—is the real reason why we have been so ineffective in dealing with poor governments. And yet, as the U.S. engagement in Afghanistan should teach us, the failure to make the hard choices is also costly. It causes us to fail to predict the actions of poor governments because we do not know how they govern, or what incentives or constraints they face. When we stigmatize the governance strategies of poor governments, we make it difficult to have real conversations about how poor governments work or how they can work better. When we base our development and security strategies on unattainable changes in the way in which poor governments hold power, they fail, at the cost of money and lives. When we set ethical and performance standards for poor governments that are unachievable no matter what they do, ironically we free poor governments from being accountable for ethical behavior and performance. If poor governments can’t afford the kind of governance we want, then campaigning to universalize our governance values as the only legitimate basis of governance risks destabilizing poor governments without offering any viable alternative. At the same time, the failure to develop an explicit foreign policy to engage poor governments effectively delegates that responsibility to the clandestine services and field-level personnel. This means that the approach will be piecemeal and focused on solving immediate problems without consideration of the full scope of the national interest. It also leaves these on-the-ground problem solvers without useful guidance and vulnerable to later reproach or punishment.

Most people want to turn the discussion back immediately to the question of how poor countries can become rich in the hope that this will obviate the need to develop an adaptive foreign policy for the long interim. But this is not a book about how to fix poor governments, and it does not offer a technical solution. It does not suggest how poor governments should govern or how poor countries should become rich. This is because the problem with which this book is concerned is a political problem, not a technical one, and it is a problem with us, not poor governments. If poor governments cannot change the way they govern in the medium or perhaps even the long term, then we must change the way we respond to them. This book is an appeal to allow a different kind of conversation about the governance of poor governments.

DESTIGMATIZE. By painting poor country governance as an exclusively moral issue, we drive the issue underground; but it cannot be the case that to be moral one must be rich. Destigmatizing the governance of the poor would allow a more honest exchange with poor governments and their citizens about the way they are governing and why and what types of reforms and improvements might be possible. Accepting the governance strategies of the poor would mean abandoning denunciations and ultimatums because we would not want to undermine the government’s ability to govern, and we do not have workable suggestions for alternative ways for the government to hold power. We would drop the use of the word “corruption” to describe governments that govern through patronage. “Corruption” is not accurate to describe patronage systems, insofar as it refers to deviant, not routine, behavior; nor is it helpful, since it is also a term of moral condemnation.

DECRIMINALIZE. We would also have to decriminalize these governance practices and allow them to be legalized in international and poor country domestic law. For example, if the government cannot pay civil servants regular and adequate salaries, then civil servants must legally be allowed to monetize their offices or to hold outside employment, just as government officials were allowed to do when Western countries were too poor to pay them salaries. If legalized and thereby made more transparent, such practices might more easily be publicly discussed and bounded by norms, like public-private partnerships or outsourcing. Poor governments would not be pressured into signing treaties that criminalize their strategies of governance, such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. The human rights community would need to, at a minimum, take a much more limited view of the role of poor governments in guaranteeing human rights and, at a maximum, be willing to tolerate some degree of political repression. By bringing the domestic law back in line with the possibilities, actualities, and norms of poor government governance, the legal system could be made meaningful and rule of law might become more possible.

DEVELOP REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS. We would lower our expectations of poor governments substantially, and in particular we would not encourage them to overpromise, by, for example, pressing them to pass laws, sign treaties, or hew to benchmarks that commit them to provide services or guarantee rights that they cannot afford to provide or guarantee. We would limit our demands on poor governments for information, interaction, reform and implementation, the protection of human rights, transparency and democracy, and the delivery of more and better quality public goods and services to a wider set of users. Poor government accountability would be strengthened if the responsibilities of poor governments were reduced and brought back into alignment with their capacities, resources, and governance strategies.

DEVELOP NEW STANDARDS. All poor governments are not the same. We would develop more nuanced standards appropriate to poor governments to judge the quality of their governance. Instead of measuring poor governments against a single unattainable governance ideal (an ideal that even rich liberal democracies do not attain), we would judge them against governance possibilities that are within their grasp, keeping in mind the way in which they do and must hold power and comparing them to other similarly situated governments. We would distinguish between strategies we liked better (perhaps patronage) from strategies we did not like as much (perhaps repression). We could even distinguish between better and worse patronage systems and between better and worse repressive governments. Just as citizens in poor countries do today, we would distinguish between those who take and those who take “too much”; those who share with others and those who “eat alone”; and those who take but get things done and those who take but do not deliver. We may distinguish between patronage systems based on their inclusion, stability, legitimacy, or involvement with international crime. Likewise, we could distinguish between repressive governments that use repression modestly and in predictable ways and those that have such disproportionate and unpredictable responses to challengers or conduct themselves with such impunity that even apolitical citizens live in fear of their government. There is a qualitative difference, for example, between North Korea and Rwanda.

We would encourage deeper thinking about how better outcomes are achieved in the world of second-best governance, which can only be done by acknowledging how poor governments do and must govern. The question is not whether such regimes are desirable, but whether they are the best available under existing constraints, and at the center of this analysis must be the question of how a government is to govern because a government that cannot govern cannot do any other thing. The governance of poor governments should be compared with a counterfactual, not an ideal, vision.

Some scholars are drawing such distinctions already, although our foreign policy has not. Fukuyama, for example, has argued that a distinction should be drawn between clientelism—in which democratic politicians and political parties deliver benefits to their electoral supporters—and corruption—in which politicians simply take for themselves.

49 Other studies have drawn distinctions between the impact of bribe demands when the amounts to be paid and the persons to whom they should be paid are well known and the services paid for are reliably delivered, and decentralized corruption, where there is uncertainty about whom to pay, how much services cost, and whether they will be delivered once payment is made.

50 Similarly, Johnston has argued that political machines are superior to decentralized corruption because they do deliver some level of services and that the existence of cartels of elites can be consistent with economic growth and gradually improving governance.

51 A large body of scholarly work has debated the benefits of development-minded authoritarian regimes, such as those of Singapore, China, predemocracy South Korea, and Rwanda, as long as they deliver the goods in terms of economic growth, human development, and the gradual expansion of the quality, breadth, and depth of public goods and services.

PRESS FOR IMPROVEMENTS THAT ACKNOWLEDGE HOW THE GOVERNMENT HOLDS POWER. Within the community of Western governance experts, the problem of strengthening governance in poor countries has often been seen as a problem of sequencing: figuring out the optimal order of steps and focusing on building “the basics” first. This approach embodies an optimistic view of our understanding of how complex social systems operate and the possibilities of social engineering, as if governments were designed and built by clever technocrats instead of emerging as the product of political processes. (It is worth remembering James Madison’s caution that the U.S. Constitution is a political outcome, rather than the product of an ingenious theorist working in his closet.

52) But even if it were allowed that Western governance experts have the ability to design and create other peoples’ governments, the problem is not simply one of sequencing if we don’t know what the end product is. The sequence of steps in building a skateboard is not the same as the sequence of steps in building a sports car; nor should the two be judged by the same criteria.

Understanding that poor governments hold power differently would mean abandoning the insistence on transferring “best practices” in governance, laws, institutions, or ethics codes to poor governments that cannot use them, given how they govern, and cannot afford to implement them. The transfer of Western formal institutions is unlikely to change the way poor governments hold power, and therefore, if transferred, such institutions are not likely to work the same way for poor governments as they do for rich ones. Scholars and practitioners have raised this point, repeatedly, since the beginning of this institutional transfer project.

We can and should still press for better governance, but it would be better governance within the framework of the strategies available to the government for holding power. Instead of starting as a point of departure with what governments that are thousands of times richer do, much less what an unattainable governance ideal looks like, we would ask, “What does a good $200 or $300 or $600 per person per year government look like? How would it garner political support? How would it hold power? How would it deal with challengers? What functions can it carry out? How much of its territory could it really govern? Who, if anyone, can govern the territory it cannot?” There can be no single right answer to these questions.

Because governance according to the governance ideal is not an option, taking the constraints of poor governments seriously might mean supporting a shift in governance strategies from one suboptimal strategy to another. It might involve working to support the establishment of a political machine as a better alternative to a decentralized and disorganized corrupt state that delivers no services, helping to build more effective, equitable, transparent, or stable patronage systems, or working to replace an unpredictable and violent system of political repression with a more restrained and predictable one.

Finally, acceptance of the governance implications of poverty calls into question the transferability of the expertise of Western technocrats in the governance domain. There is no reason to assume, for example, that the domestic experience of Western procurement specialists or lawyers equips them with an understanding of the role and possibilities of procurement and legal systems in poor governments that hold power differently. We may know how to be a good rich government (although some would question that given our own struggles with good governance at home). However, it is much less clear that we know how to be a good poor government. The West’s experience of governing while poor is too long behind it for Western experts to have much advice on how to run a better patronage system or repressive regime, even if they were inclined to do so. There is also the question of having moral standing to advise on the difficult tradeoffs that poor governments and their citizens must make. While the West lacks expertise in this domain, it could foster South-South cooperation on governance issues between countries that have similar constraints, but only if it allows people to speak freely about how they govern without fear of condemnation or reprisal.

CHANGE THE RULES OF ENGAGEMENT. Acceptance of the ways in which poor governments govern would then allow us to discuss how to engage these governments effectively, ethically, and productively. This means identifying and engaging the decision makers regardless of their formal roles and engaging poor government processes even if they are not those written in the law. It would mean developing an understanding of how poor governments hold power and both their political constraints and the limits of their capacities. It may even mean cultivating government elites as clients in order to leverage their patronage networks. In practice, we already do these things episodically, but because the way that poor governments govern is not considered legitimate, these practices of engagement are also considered illegitimate and usually hidden from the public eye. Destigmatizing the governance of poor governments would also allow us to destigmatize these engagements with poor governments and allow the formulation of a more transparent and thoughtful foreign policy on engagement.

This pragmatic approach is not a relativist one; it is not a repudiation of our governance values. People everywhere should continue to seek government that is more effective, just, accountable, predictable, inclusive, responsive, and peaceful. However, the governance of very poor governments will never look like the governance of rich liberal democracies. It will necessarily follow a different logic and fall far short of our desires. The path to better government will be imperfect, incremental, and contextual, and more possibilities open with increasing wealth. However, the refusal to acknowledge the limitations that poverty imposes on governance not just in terms of capacity but also in terms of how governments must hold power is too expensive.