4

1096. AUGUST. WITH THE NORTHERN ARMY, PREPARING TO DEPART . . .

The Feast of the Assumption came soon enough for the thousands of knights persuaded either by conscience or Urban II’s rhetoric to stand in the fields of Lorraine and Flanders, adjusting their equipment and waiting the order that would propel a vast column of fighting men toward the Holy Land. The bright August sunshine flittering across their chain mail was a good omen.

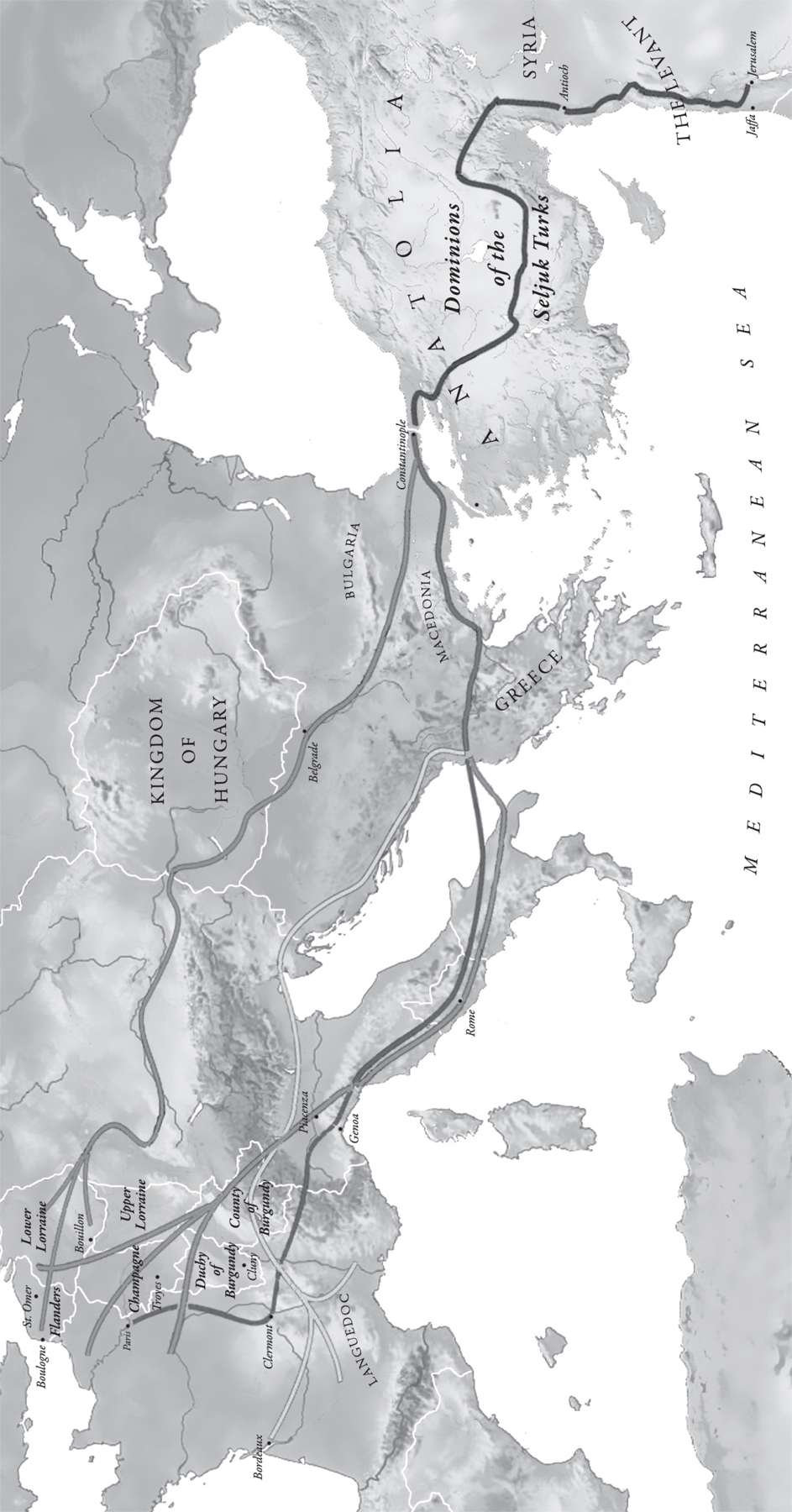

En route they were to rendezvous with three other armies of similarly inspired men marching from separate locations throughout Europe, amalgamating at Constantinople to form a fighting unit of four thousand knights and thirty thousand infantrymen. Unlike the People’s Crusade, this northern branch of the crusading army was led by Flemish nobles who commanded discipline—three brothers of Merovingian bloodline, sons of Eustace II, Count of Boulogne.1 The youngest, Baudoin de Boulogne, was a student of the liberal arts; then there was Eustace III, who had inherited the title of Count of Boulogne after his father’s death; and finally, tall, blond, bearded, and pious, a model knight named Godefroi de Bouillon.

A chronicler of the Crusades named Raoul of Caen described Godefroi thus: “The lustre of nobility was enhanced in his case by the splendor of the most exalted virtues, as well in affairs of the world as of heaven. As to the latter, he distinguished himself by his generosity towards the poor, and his pity for those who had committed faults. Furthermore, his humility, his extreme gentleness, his moderation, his justice, and his chastity were great; he shone as a light amongst the monks, even more than as a duke amongst the knights.”

And just as well, because being the second of three brothers, Godefroi stood to inherit little and was thus afforded fewer advantages in life. That is until his uncle Godefroi the Hunchback (son of Godefroi the Bearded) died without an heir and bequeathed the lordship of Bouillon to his young, enlightened nephew.

As the crusading armies threaded their way through the kingdoms of central Europe, they encountered a populace browbeaten but wiser from the marauding behavior of their forerunners, the People’s Crusade. Aside from a few skirmishes with the Greeks and an incident in Hungary—in which Baudoin volunteered to be held in ransom by the king to ensure the proper conduct of the armies through his territory—things generally went smoothly.

By November 1096, Godefroi de Bouillon and his mounted knights and infantrymen were within reach of Constantinople when they came under sporadic harassment by troops that later turned out to have been sent by Emperor Commenus. Perhaps after his experience of the People’s Crusade the emperor had become suspicious of the help Urban II was sending his way; furthermore, the presence in the arriving army of the emperor’s old nemesis, Prince Bohemund, did little to appease Commenus’ paranoia.

Nevertheless, within four months all the Crusaders combined at the gates of Constantinople. They required sustenance and expected this simple courtesy from Commenus.

Commenus made promises and then broke them. Advances were betrayed by hostility, further irritating the soldiers. Then he demanded their sworn obedience and fealty. When he received neither he attempted to subdue them by famine while lavishing great feasts on selective knights—a potential candidate for multiple personality disorder. But the year was drawing to a close and winter called. Finally the Crusaders had had enough and resorted to plundering the countryside.

The year 1097 arrived, and still Anatolia beckoned the Crusaders from across the narrow waterway of the Bosphorus. The rocky chasm separating Europe from the East perfectly reflected the impasse between the knights and their neurotic host.

It was at this point that Godefroi de Bouillon must have detected an ulterior motive behind the pope’s push for a Crusade. As far as this knight was concerned, his intent was to march to Jerusalem, liberate the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and reestablish the accord between Christians and Arabs, even if it meant a fragile one. It was a clear plan, yet Commenus provided nothing but obstacles; in fact, he now demanded an oath of obedience from the nobles in charge of the armies. To all intents and purposes, the Crusade appeared like an opportunistic accord between the pope and the Holy Roman emperor to commandeer soldiers and rid the Turks from the emperor’s lands.

For Godefroi, the reality of the situation was that tens of thousands of men needed to be ferried across the Bosphorus. They could build their own ships for the short hop, but that would take months. Commenus knew this; he also owned all the vessels in Constantinople. The only way forward was diplomacy and compromise, so Godefroi and the nobles convened with the emperor, whereupon the ever-scheming Commenus proposed a modified oath. In return for the ferrying of troops into Turkish territory the army leaders agreed to assist him by marching on the city of Nicaea, attack the Turks in their stronghold, and liberate the city in the name of Christendom. Godefroi grudgingly agreed to the modified oath; Raimond—another leader of the army—told Commenus politely to go stuff himself, but at least gave a pledge not to attack him.

And so it was that by the spring of 1097 the Crusaders finally made landfall in Anatolia with the help of the emperor’s ships. However, even as Godefroi’s army prepared to lay siege to Nicaea, they discovered Commenus had made a secret treaty with the Turks, in which the surrender of the city was ensured to the emperor, thus making it look as though his Byzantine army, not the Crusaders, had won the conflict.

Godefroi and the other leaders of the Crusade.

Following the betrayal, Godefroi and his brothers, along with their respective Crusading armies, turned south toward Jerusalem and resumed their original intent.