17

1127. AUTUMN. ABOARD A GALLEY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN . . .

Hugues de Payns was born in Chateau Mahun near Annonay in the Ardèche,1 into a family branch of the dynasty of the Counts of Champagne.2 He married Catherine de Chappes,3 whose relative, Henri de Saint Clair, crusaded with Godefroi de Bouillon.4

His grandfather, being Moorish, would have instilled in young Hugues an appreciation of the benefits of cross-cultural pollination, particularly with the Islamic world, which at the time was light-years ahead in education in Europe thanks to its knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, learned from the Egyptians via their impressive library at Alexandria, one of the great academic wonders of the world—at least before a fanatical mob of Christian fundamentalists burned it down. As such, he would have been exposed to Islam’s esoteric branch, Sufism.

Around his 33rd birthday Hugues spent much of his time traveling throughout Asia Minor, possibly to widen his wisdom, probably to find a deeper purpose in life. By the time of his second voyage to Jerusalem around 1114, he had already counseled with kings, received counts from Europe, lived in not just one but two of the world’s most famous religious temples, created a new order of warrior monks from scratch, and on May 2, 1125—the Celtic fertility feast of Beltane—he had become their Grand Master.5 Not bad for a minor noble from an otherwise obscure town who gave up his riches to become poor of pocket but rich in spirit.

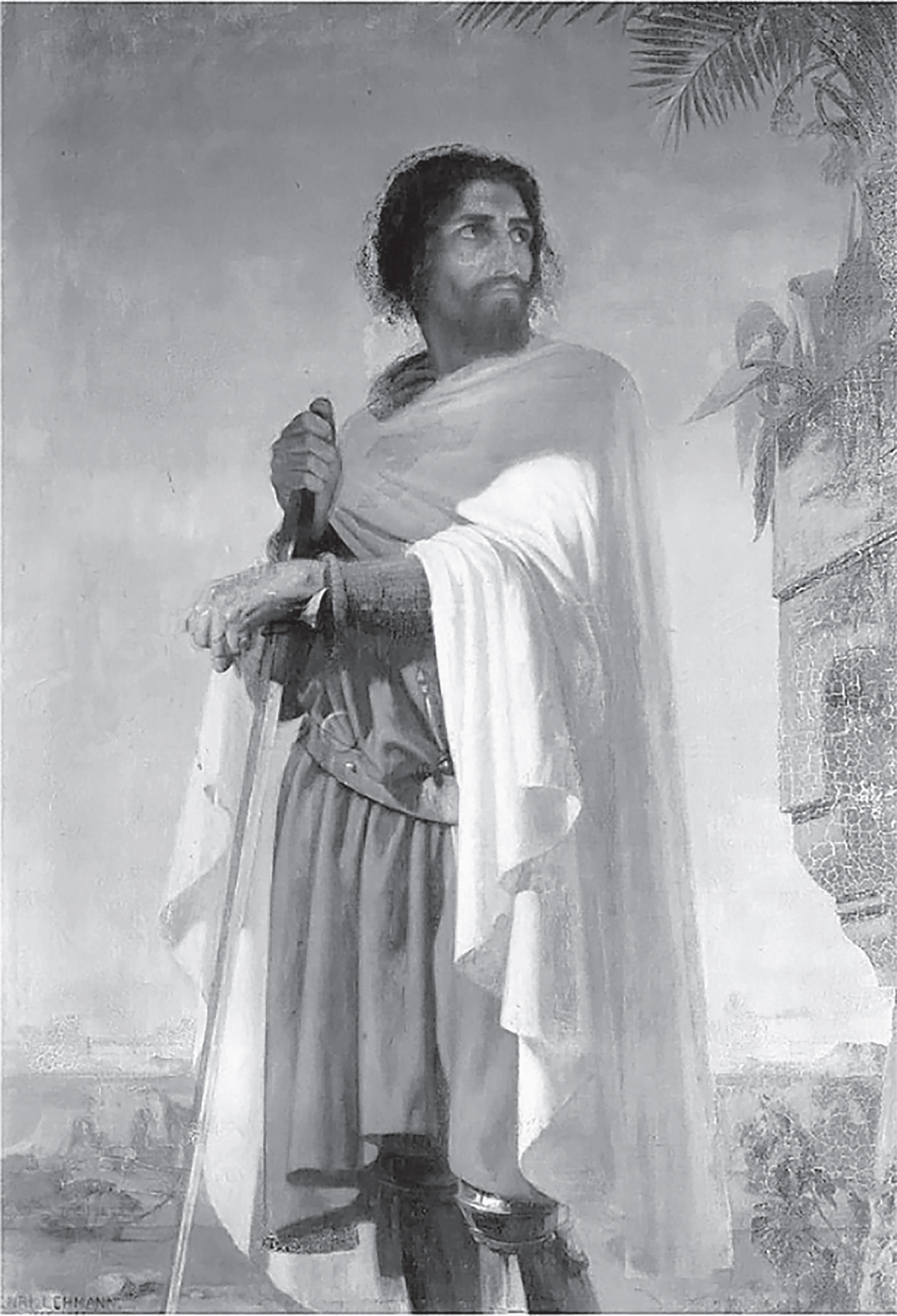

Hugues de Payns.

This much may have been sailing through his mind as he stood on the deck of the wooden galley, watching the harbor at Jaffa diminish in the distance, replaced by a wide expanse of blue Mediterranean, finally substituted for the limestone shore of southern Italy. The work the Templars had been secretly pursuing on Temple Mount was complete, and now they were on their way back to Europe to set events in motion. Accompanying Hugues on this voyage were at least five Templar brothers.6

Two years earlier he had dispatched another group of knights to Portugale, including his colleague Arnaldo da Rocha,7 but not before the two leaders cosigned a document affirming the continuing relationship between their respective Orders.

There was much to do and his mind should be clear: first, he would travel to Rome and meet Pope Honorius II,8 who was on good terms with the Cistercians, least of all because he too did not see much bene in the behavior of the Benedictines. To the pope, he would put forward a strong case for receiving a blessing for his “new” knighthood. Like it or not, few favors were granted in twelfth-century Europe without a nod of approval from Rome, and even as Buddhists well preached, with your arms wrapped around your enemy, he cannot fight you.

Hugues also ensured the Cistercians were kept abreast of the progress on Temple Mount. Only last year he had sent his Templar brothers André de Montbard and Brother Gondemare as envoys to brief Bernard de Clairvaux.9

Once his affairs were completed in Rome, he’d journey north, through Burgundy to Champagne, and meet with Bernard—longtime friend, relative, spiritual compass, benefactor—before presenting himself at an ecumenical council, which no doubt would be convened after the pope heard what he’d come to say.