25

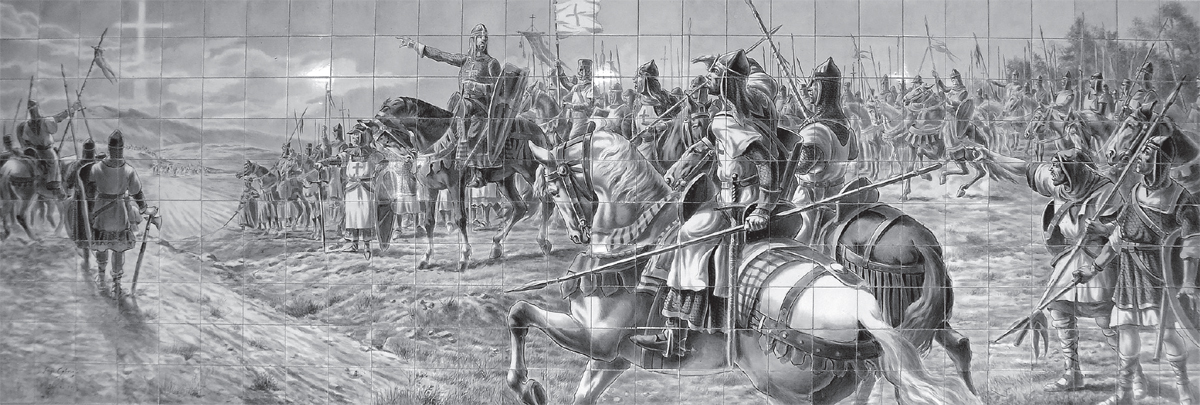

1139. OURIQUE. PREPARING TO BATTLE THE MOORS . . .

A mid his new duties as head of an independent state, Afonso never forgot the importance of the role played by his mentor, the Templar sympathizer Payo Mendes. A month after taking up residence in Guimarães, the ebullient prince made a generous property donation to his friend in anticipation of the day “when I have acquired the land of Portugal.”1

If Afonso was under any illusion that the day he would own the remaining Portuguese territory would come easily or soon, it was quickly dispelled. Although the threat from the armies of Castilla e León in the north was temporarily in check, the Moors had reoccupied Portuguese lands south to the river Tejo once liberated by his father, including the city of Lisbon. A definitive blow had to be delivered to the Arabs, and that day arrived eleven years later on the plains of Ourique.

The Moors obviously viewed the impending skirmish as a potentially defining moment in Portuguese solidarity, given how they mustered the combined forces of no less than five caliphs. In the decade since the Portuguese had taken the city of Guimarães, the Arabs painfully watched the successful southward reconquest of territory, so much so that Afonso Henriques was able to move the seat of power eighty miles south to Coimbra, a historic city abutting the frontier territory currently under Arab dominion. The move gave Afonso room for a fresh start, a break with the old politics of the established territories of the north and the dense intricacies of aristocratic privilege that hampered forward progress in building a nation-state.2

No sooner had he settled into his new abode when, contrary to military preparedness, his first major activity in the city was to attend to the founding of the monastery of the Holy Cross for a community of regular canons of Saint Augustine, which would feature as a major urban property along the city’s walls. By conventional military terms this was an odd endeavor in a time of war, and war there was aplenty, starting with the thousands of gathering Moorish forces whose swelling ranks gradually masked the contours of the rolling plains around Ourique.

The Portuguese army began preparations around July 22, the feast day of Mary Magdalene. Three days later, the tall figure of Afonso Henriques walked pensively toward the head of his army, his mind oscillating between the demands of military preparation and the prophetic dream he had experienced the previous night, in which he was convinced his armies would prevail on the battlefield. His reverie was interrupted by a contingent of nobles and knights approaching him, among them Guilherme Ricard, the first Templar Master of Portugale, who took the prince by surprise with an unexpected proposition. Following a secret meeting of the gathered lords, it was their unanimous wish that Afonso be declared king of Portugal before the commencement of hostilities.3 Afonso was startled: “My brothers, it is my honor to be your lord, and I feel well served and protected by you, and because I am satisfied with this I do not wish to be called “king,” nor to be one, but as your brother and friend I will help you with my body to defeat these enemies of the faith.”4

Battle of Ourique.

But the knights insisted. Not only was it their desire, but given the insurmountable odds faced by the Portuguese troops against a vastly superior Arab army, the men would doubtless be encouraged at the prospect of marching into battle behind a monarch.

Afonso reluctantly accepted the honor, like an echo of his predecessor Godefroi de Bouillon when he too was offered the title of king of Jerusalem without his solicitation and during the same time span of July 22 to 25.*14 Following a brief ceremony on the battlefield, Afonso’s horse was brought forward, covered with his customary white mantles; his knights rode left and right and took charge of their respective flanks, and the battle to rout the Moors commenced.

Hostilities raged for three hours beyond midday in the stifling heat of July, both sides made indistinguishable by the orange dust propelled skyward by hands and feet engaged in fevered combat. Against all odds, the Moors were vanquished.

By July 25, the triumph was complete. Afonso commemorated the event by amending the shield of Portugale he carried with him, an inheritance from his late father—the blue cross over a field of white—to incorporate thirty silver bezants, a reminder of the symbolic entry requirement into the Templar Order.5

Three days after the cessation of hostilities, Afonso returned to Coimbra and the monastery of the Holy Cross, where he met with its prior, Dom Telo, for advice on the issue regarding prisoners of war, not to mention the scores of Arab citizens who in a twist of fortune suddenly found themselves under Portuguese domain. The aged prior suggested to the victorious king the honorable course of action would be to take the high ground: show mercy, for even the Cistercians would acknowledge that to fight a war for war’s sake defeated the purpose of the spiritual warrior. By setting an example, in time one’s enemies may become friends.

The new king listened. A pardon was announced and Muslim prisoners were released.6

Afonso then rode north to gather the first assembly of the estates-general, and in a cathedral ceremony at Lamego—a stone’s throw from the first Cistercian monastery he once helped a group of monks from Clairvaux to found in Portugale—Afonso Henriques was officially crowned King of Portugal by none other than Payo Mendes.

When he arises, he does so not just as head of an independent country but also as king of Europe’s first nation-state.7