33

1947. QUMRAN. TWO GOATHERDS, IN A CAVE, BY THE DEAD SEA . . .

Muhammed and Ahmed of the Ta’amireh tribe stumbled upon the weathered scrolls buried in one of the caves beside the ruins of a former community of mystics called Essenes, who existed around the time of John the Baptist. Until this fortuitous moment, the “treasure” of the Essenes was considered all but lost.

The crumbling parchments*20 revealed that in addition to a stockpile of gold bullion and silver ornaments hidden under Temple Mount from an advancing Roman army, “an indeterminable treasure” had also been secreted there.

Treasure typically implies one thing. Money. The sudden rise from rags to riches by the Order of the Temple indicates the brotherhood directed all its resources to find, dig, and spend a hoard of loot. And yet if they become overnight millionaires from this Essene heist, why should they need or even accept an unprecedented sum of donations from people all over Europe? Furthermore, the central caveat for joining the Templar Order was the renouncement of personal wealth; in fact, all knights had to honor a vow of chastity, obedience, and to hold all property in trust.*21 Clearly, money or the accumulation of personal wealth was not a prime motivation. Had the knights been looking for buried treasure there were far easier ways for noblemen to get rich than to become knights but work as miners laboring for years through solid rock in dangerous and hot and claustrophobic conditions! They could just as easily have held on to their inheritances.

A clue appears in the original rites of Royal Arch Freemasonry, in which the ritual of entry into the three degrees describes, allegorically, how the Templars found a secret buried chamber under Temple Mount. Access to this chamber is said to have involved the removal of a rectangular keystone with an iron ring. Once lowered inside they discovered an important scroll, but “being without light” they were unable to interpret the information it contained.1 Once they had “received light,” however, the men came to understand its knowledge.

The light they required did not come from a torch but its figurative interpretation: enlightenment. (In the Masonic ritual the initiate is blindfolded; then the blindfold is removed.) From that point the initiate undertakes an obligation to rebuild the former temple.2 To all intents and purposes the ritual is a reenactment of a true event, and the scroll is nothing short of an archive containing spiritual laws, the Word of God.

The word archive derives from the Greek arkheia (magisterial residence), a very apt description for a place where God resides; its root is arkhe. But there’s more. Still assuming that the Templars were seeking nothing more than financial treasure, an examination of the etymological fingerprint of that word reveals otherwise. Treasure in Portuguese is tesouro, whose Greek root is thesauros (a storehouse, a treasure). Interestingly, in old Portuguese both words are interchangeable and synonymous with a treasure of learning, the latter often equated with books or a library.3 So in a manner of speaking, the Templars did discover a treasure, but not so much a treasure of gold as a treasure of words.

But an ark containing a treasure of words? Are we dealing with a receptacle housing laws that, metaphorically speaking, descended from a very high source? Did the Templars recover the Ark of the Covenant, or perhaps some of its contents?

It is written that the temple of Solomon was built for the singular purpose of housing the Ark, and just before its Holy of Holies was breached by an encroaching Babylonian army, the sacred box was sealed in a secret room beneath Temple Mount.4 It is also written that the Laws of God placed in this receptacle were important enough to merit that any stranger who approached the Ark without proper training was punished on pain of death. This seems rather a harsh attitude. But if by “stranger” the account actually refers to a non-initiate, this would be consistent with Egyptian Mysteries schools’ principles in which only adepts and initiates of the temple could be entrusted with hermetic and gnostic secrets lest such knowledge be used irresponsibly.

The laws placed in the Ark of the Covenant should not be confused with the Ten Commandments, because those are hardly secret; even by Moses’s time, around 1300 BC, they were commonplace. In fact, these Commandments—all forty-two of them—were already in vogue as the Utterances of the Pharaoh during the time of Thutmosis III, affirmations for the orderly conduct of one’s personal life to ensure a favorable outcome when the soul finally departs the physical body for the afterlife.

In truth the Ark contained far more than Commandments. According to scripture, when God instructed Moses to come up to Sinai, he said, “I will give thee tables of stone, and a law, and commandments which I have written, that thou mayest teach them.”5 That’s three separate items. In Exodus 34:27–28 it is made clear that the Tables of Testimony were written by God, and the Ten Commandments were written separately by Moses. The church has strategically ignored the Tables and focused on the Commandments as the important issue.6

With regard to the Templars, it is the Tables of Law that are of interest because they supposedly contain a kind of cosmic equation. They are a precious instruction, an understanding of creative forces at work in nature. Anyone in possession of such information has direct access to how the universe functions and the very laws of cause and effect. The power of the land is said to be derived from these instructions; thus, they are in themselves a means of power and certainly not meant to be entrusted to the ignorant or the foolish.

Secrets of this magnitude deserved to be well protected. Any fool determined to get past the heavily armed Levite guard faced an electrified Ark, followed by a perimeter of unspecified defenses that proved so effective that it gave the Philistines who approached it hemorrhoids. Even if they survived these trials, the tablets containing the word of God could only be read by a person initiated into the secret Mysteries—such as Moses, who was an adept of the Egyptian Temple.7

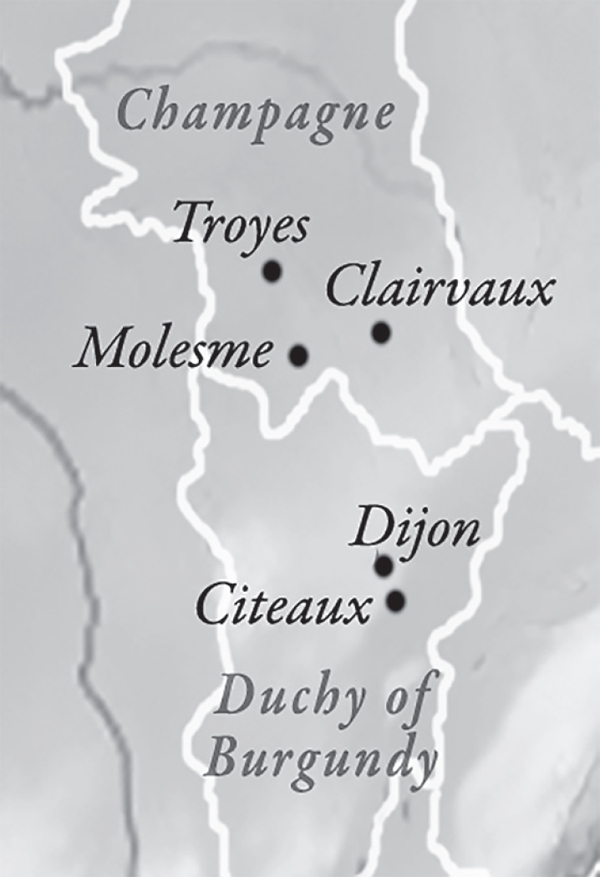

Initiates, adepts, and Mysteries schools were not in short supply in the enlightened duchies of Burgundy and Champagne of the eleventh century. Kabalistic schools may have existed there three centuries earlier when Jews were granted a kingdom within a kingdom and insisted to have at its head a recognized descendent of the Royal House of David. This took shape in Count Guilhelm de Toulouse, a Merovingian, who acceded to the throne as king of Septimania, as the region was then named.8 Later, persecuted Jews found a new sanctuary with the enlightened Counts of Troyes and Champagne, particularly the Templar supporter Comte Hugh de Champagne, who sponsored an influential school of Kaballah and other esoteric studies that flourished in the town of Troyes around the year 1070. This Mysteries school was founded by Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac, or as he was affectionately called, Rashi, a man of great intellectual repute with an obsession for procuring information on the Ark of the Covenant. And given that he resided in Troyes,9 he was a frequent guest at the court of Comte Hugh de Champagne.

This Kabalist school, then, was well funded and placed and prepared for the continuing cryptic translation of documents found by the Templars under Temple Mount, especially as Lambert de Saint-Omer passed away shortly after receiving the first scrolls from the Templar knight Godefroi de Saint-Omer.10 A scroll named Seper Yatzirah (Book of Formation) was given particular attention because it allegedly provided a guide to the creation of the universe. It was the most mathematical of all the scrolls, as though it were a formula or manual of manifestation or, in a manner of speaking, a kind of holy Graal.11 Naturally, its esoteric contents were to be made accessible to no one but the pious and only then under certain conditions.

A second man who took a great interest in such Kabalistic studies was Stephen Harding, a clergyman who gave up a seat at Sherbourne Abbey in England to become a traveling scholar in France. En route to Molesme Abbey (a few miles south of Troyes), Stephen became acquainted with Rashi,12 and no doubt his esoteric studies shaped his worldview when he became abbot of the Cistercian abbey at Citeaux.

Solomon ben Isaac, known as Rashi.

In 1112 Stephen had the opportunity to share this passion for Kaballah’s spiritual philosophy with a visitor to the abbey, a young monk by the name of Bernard de Clairvaux. When Bernard later created the abbey of Clairvaux, 33 miles southeast of Troyes he maintained the collaboration with the Kabalist school.

The knowledge transmitted at this school involved an understanding of sacred geometry, especially with regard to Solomon’s Temple. Chief among Solomon’s masons—the so-called Children of Solomon—was their master mason, Asaph, an architect skilled in the importance of geometric harmonics and the behavior of resonance, particularly as applied to sacred buildings. Such “masters of the craft” were denoted by degrees of knowledge and proficiency concerning universal laws. It is probable, then, that Bernard was taught to understand and apply the sacred geometry of Solomon’s Temple contained in the scrolls, because when asked to describe God, Bernard cryptically replied, “He is length, width, height and depth.”13

That God is geometry is something every Muslim knows, since the elaborate geometric tile work prominently featured in every mosque is said to depict the face of Allah; the same truth is encapsulated in every mandala, be it from a Buddhist monk or a Native American shaman, and it is claimed that working with such geometry induces an altered state of awareness.14

On one level, it would seem that the treasure rediscovered by the Templars during their digs was a thesaurus of cosmic laws that included the secrets of geometry and harmonics, knowledge sacred to architects of pyramids, temples, and other holy places. These savants were keenly aware that such harmonics are capable of inducing the kind of shamanic experiences that lead to a personal and mystical experience of God.15 That the Templars applied this knowledge became obvious when the first Cistercian pope allowed them the unique right to build churches whose round form and octagonal geometry generate acoustics of such clarity they are capable of inducing trance-like states in the listener.16 Even the pillars of the buildings produce a ringing tone.17

The understanding of the Templar and Cistercian architects was certainly advanced for medieval times (it is exceptional even by modern standards),18 leading one contemporary eyewitness in Jerusalem to remark, “On the other side of the palace the Templars have built a new house, whose height, length and breadth, and all its cellars and refectories, staircase and roof, are far beyond the custom of this land. Indeed its roof is so high that, if I were to mention how high it is, those who listen would hardly believe me.”19

Within six years of returning from Temple Mount they introduced this knowledge into Europe in the shape of Gothic architecture. Gothic is derived from the Greek goetia (by magic force); its extension is goeteuein (to bewitch), a rather appropriate term given how the spatial relationship of the buildings generates frequencies that find their correspondence in the human body, particularly DNA,20 not to mention the pineal gland,21 as well as the area of the brain associated with mystical experiences, the amygdala.22

One of the first cathedrals to be erected in the Gothic style was Saint Denis in Paris, on the site of a previous structure founded by Dagobert I, a Merovingian king. In Portugal, the Gothic style appeared in 1153 when Afonso Henriques laid the foundation stone for the breathtaking Cistercian monastery of Alcobaça, a building of superlative acoustical properties built in honor of his uncle Bernard de Clairvaux. But perhaps the most bewitching of all Gothic buildings is the one that arose to the west of Troyes: Chartres cathedral.

Every facet of this temple reveals information, be it overt or coded, much like the Egyptians did with the Great Pyramid of Giza.23 Bernard de Clairvaux himself held daily consultations with the builders,24 and a careful look at the pillars framing the Door of the Initiates leaves no doubt as to where the knowledge came from. A relief carved in limestone depicts the Ark of the Covenant transported on a cart, its open lid revealing a tablet and an orb inscribed with the fleur-de-lys, symbol of the holy bloodline in France; beside it, a man conceals the wooden receptacle with his robe, flanked by four individuals who look as though they are ascending a stairway to heaven. On the pillar is inscribed the accompanying phrase, “Here, things take their course; you are to work through the Ark.”25

It is as though the cathedral is a sermon by Bernard set in stone.

This was by no means the only craft known to Bernard de Clairvaux. He would sometimes let on that he was well versed in cryptography by using it playfully in his many works, particularly his sermons. The Latin text of the Song of Songs—referring to Bernard’s experience of the divine—consists of exactly ninety-nine syllables. In Roman numerals this would be written IC, the initials of Iesus Christos.26 Another coded reference exists in the final quotation of sermon 74 of Super Canticum, which consists of exactly 159 syllables. In Roman numerals this is written CLIX. Since X was often interchanged and equated with S, the letters read CLIS, a common contraction for CLARAVALLIS, the Latin for Clairvaux. The abbot is suggesting his mystical experience of God is closely associated with his place of residence, an unusual choice of location for an abbey to begin with, where a person could live, move, and be in God. Such cryptic language suggests he knew the choice of location coupled with the spiritual practices conducted in a specifically shaped building were paramount to achieving the shortest route between the material world and another dimension.27

The Ark of the Covenant on the Door of Initiates at Chartres cathedral.

When they first arrived in Jerusalem in 1104, Hugues de Payns and Comte Hugh de Champagne carefully surveyed Temple Mount and ascertained the challenges involved in reaching their predetermined goal. They returned a decade later, perhaps a little wiser, because by then they knew where to dig and what to find when they got there. Since a number of the original Templars were also Cistercians (Brothers Roland and Gondemare, in particular28), if Bernard de Clairvaux was privy to knowledge gained from the Kabalistic school of Troyes, it is feasible he then transmitted it via these knights to the other Templars. He knew in advance that locked inside that sacred hill were documents holding the greatest of all treasures.

If the Templars found such documents outlining the process of initiation into the art of spiritual resurrection, it may explain why so many nobles and laypeople alike readily gave the Templars so much of their personal wealth, assistance, or protection. The Catholic Church was as loathed as it was corrupt, a symbol of oppression, and many monarchs merely paid lip service to its authority just to keep the peace or stay alive. What the Templars offered was a way out, a route for every candidate of the Mysteries to find self-empowerment through a direct experience of God—“the joys of Paradise,” as Templar recruits claimed.

In a manner of speaking, Lambert de Saint-Omer was literally following the advice of Jesus a thousand years earlier, when he said to the apostles, “To you was given the Mysteries of the kingdom of Heaven. But others only see them through parables, so that when looking they do not see and hearing they do not understand.”29 Indeed, and when these Mysteries of initiation were recorded by the Essenes they were encrypted from profane eyes, their true meaning revealed only by those deemed worthy of receiving secret instruction.

To the east of Saint-Omer lies the library of Ghent University, where a twelfth-century work titled Liber Floridus survives. It is a copy of a diagram found in the Essene scrolls and depicts the heavenly Jerusalem: a walled city with eight entrances inside a vesica piscis (the geometry depicting, with the Divine Feminine, the balance of opposites). Inside stand twelve towers, along with motifs of the square and compass, the prime emblem of Freemasonry. The foundation of this heavenly city is attributed to John the Baptist.30 The picture is the work of Lambert de Saint-Omer. Obviously, he decoded what was concealed in the scrolls brought back from Jerusalem by Godefroi the Templar.*22

Lambert’s decoded heavenly Jerusalem.

It appears the Templars found the keys to the heavenly Jerusalem. And they may have undertaken an obligation to re-create it in a Portuguese municipality called Ceras, and specifically its dilapidated town, Thamara.