40

PRESENT ERA. APRIL. INSIDE THE ROTUNDA OF TOMAR . . .

The plain Cistercian interior of the rotunda lasted four centuries until it became unfashionable for a house of God to resemble the domicile of a hermit.1 What once was a soaring arc of eight plain columns within a circular ambulatory eventually became a decadence of decor and polychrome statues, proving the Baroque maxim that what is wo512rth doing is worth overdoing. Bernard de Clairvaux would be venting liquid magma were he standing beside me right now. I could almost hear his famous admonition of the Benedictines bouncing off the rotunda’s lofty walls: “I say naught of . . . the costly polishings, the curious carvings and paintings which attract the worshipper’s gaze and hinder his attention of God.”2

It had been fifteen years since I asked myself, “Why did the Templars come to my country of origin?” The silent reply was a slow and soaring hill of research. Looking under one stone led to a maze of roots, each connected to an ever-expanding and boundless body of a benevolent monster whose intricacies became as multifaceted as the three faces of Hermes. I had asked an honest question. I had not anticipated the loudness of the reply or the controversial nature of the material I unearthed. Now I had to complete the journey by returning to the rotunda of Tomar (as it is spelled today) and the labyrinthine convent that sprouted around its core.

Interior of the rotunda. The decor was added four centuries later.

It is a maiden I adore. Only now did I become profoundly aware I had been inadvertently following a Graal quest.

One aspect of the Graal is a search for secret knowledge capable of raising an individual from the spiritual death that is life on the material plane. This knowledge derives from an ancient system of teachings spanning incalculable ages, brotherhoods, and continents, and its source material is often linked to the Ark of the Covenant. Perhaps elements of the Graal or the Ark were deposited right here. Perhaps inside the rotunda was the same marble keystone with an iron ring leading to a chamber of Mysteries, as it once did on Temple Mount. Certainly the founding of the rotunda became such a potent symbol that it remains the civic day for the town of Tomar, and until the change of calendars from Julian to Gregorian it even marked the first day of Portugal’s official civil calendar.

The rotunda, Tomar.

To reach the rotunda it is necessary to walk up the hill along a meandering old cobblestone track that leads to the Gate of the Sun. Once inside the castle walls and its well-manicured courtyard, the aroma of lavender, lemon, and orange is as intoxicating to the senses as the sight of the round temple the knights erected. Indeed, it does bear a passing resemblance to the church of the Holy Sepulcher, even the old basilica of Mount Sion—the sacred places whose allure captivated the imagination of Godefroi de Bouillon, Hugues de Payns, Count Dom Henrique, and so many other protagonists in this Templar-Cistercian drama.

The building is not so much attractive as it is bewitching and entrancing.

Its exterior circular look is in fact an optical illusion; it is a sixteen-sided polygonal structure held by reassuring buttresses. Inside, the ceiling rests on a central arcade of eight slender columns, gathered like quatrefoils and arranged in accordance to the eight-sided octagon. The space between the columns and the gallery wall is defined by the invisible geometry of a hexagram: two intertwined triangles each representing nature’s complementary opposites in perfect equilibrium, much like the symbolism behind the Templar emblem of two knights riding a horse.

The octagonal motif of the churches the Templars erected is heavily indebted to Arabic sacred architecture, which uses this geometry because it represents the fully illuminated human. It is a square unfolded twice, and just as the circle represents spirit and all that exists, so the square represents its physical counterpart, matter, and the four elements that make it so: earth, air, fire, water. The four remaining faces are representative of the invisible realm. Thus, by working with this talisman one strives to achieve utmost harmony between the material and spiritual. This was, and continues to be, the aim of all esoteric and gnostic sects.

The octagon’s derivatives are the infinity symbol and the number 8. Notable avatars associated with these talismans are Jesus, Mohammed, the archangel Michael, the Arthurian wizard Merlin, and last but certainly not least, Djehuti, patron of scribes and god of magic, healing, and wisdom. His temple is situated in Khmun (eight-town), after the group of eight Egyptian deities or natural forces who represent the world before creation.*34

The Templar inner brotherhood followed a secret doctrine,3 and so their ceremonies appropriately took place in small, secret chapels inside their temples, such as the one below their preceptory in Paris.4 What rituals were performed required total devotion to the craft, and the contents were revealed strictly to this inner brotherhood, and then only after a period of observation, typically one year. This law was broken on pain of death, as graphically described in Article 29 of the Rule of the Elected Brothers:

If a Brother forgets, either by carelessness or by gossip, and makes known the smallest part of the secret rules or what happens in Chapters at night, let him be punished according to the greatness of his fault, with detention time in chains and exclusion from the chapters. If treason is proven and he has spoken with malicious intent, he is condemned to life imprisonment or even secretly put to death if it serves the best interests of all.5

The Templars were utterly devoted to Tomar, and given what we know so far about their tendencies to follow an ancient system of knowledge, it would have been uncharacteristic if they had not adopted these practices in, around, or under the rotunda itself.

In the Copper Scroll, one of the most important buildings described in the Inner Temple court is the House of Tribute. The entrance was still known in the first century BC as the Gate of Offering, and it stood on a stone platform, each of its four corners bearing a small chamber, one of which was the Chamber of the Hearth.6 Inset into the floor was a marble slab that could be raised by a fixed metal ring to reveal an opening into a deep cavern below.7 In an adjacent chamber, the Staircase of Refuge led to an underground passageway and into the Chamber of Immersion, where, presumably, rituals such as the “raising of the dead” were performed. This may be the same chamber that stood out from the others and merited Captain Warren, the British excavator, to be lowered by rope into its rectangular form; it is the same chamber once described in the Talmud as a secret room kept for special ceremonies.

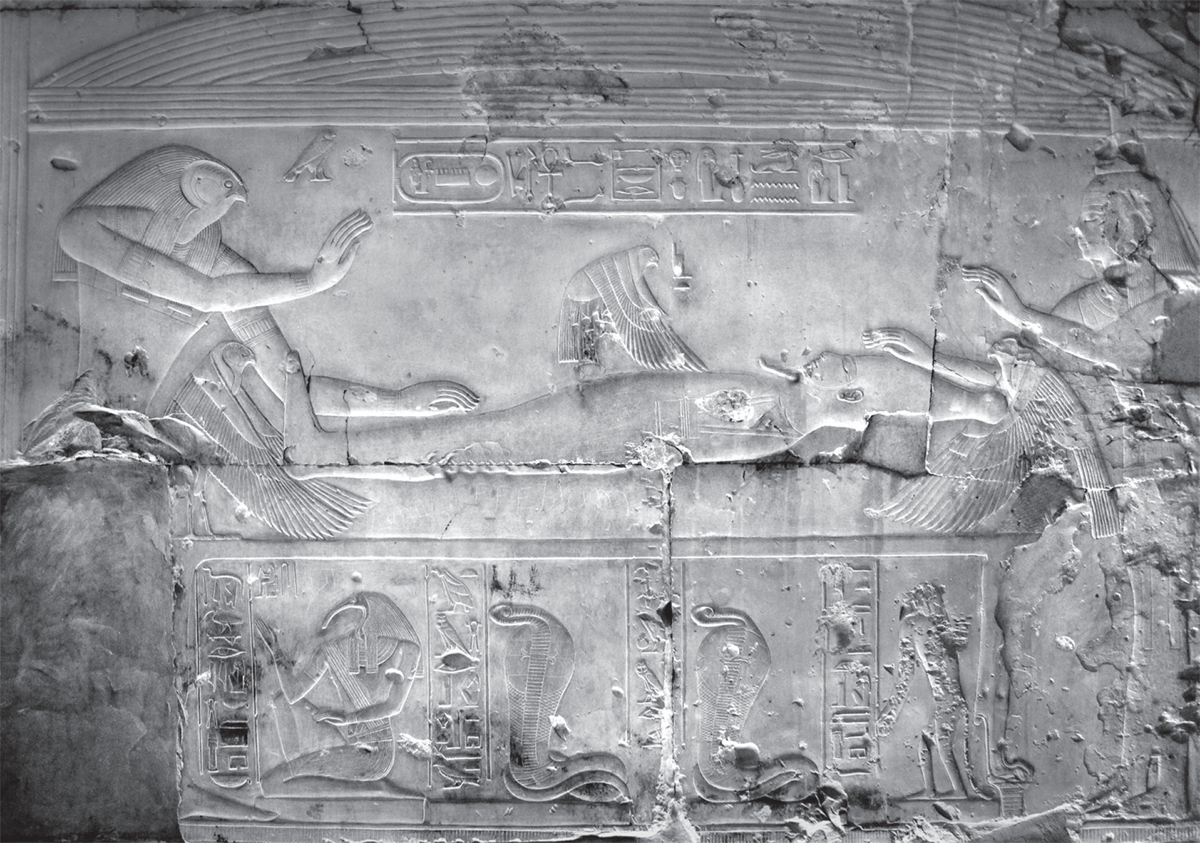

The Book of Ezekiel similarly describes how the elders of Jerusalem “engaged in secret mysteries . . . of Egyptian provenance” in darkness under the Temple of Solomon.8 Such chambers still exist beneath the altars of early churches and cathedrals throughout Europe, particularly those erected above preexisting ancient temples where identical rituals were performed. Some are well known: Chartres cathedral, Mont Saint Michel, Roslin Chapel, and so forth. In Egypt, there exists a narrow, claustrophobic chamber beneath the temple of Dendera decorated with one-of-a-kind reliefs depicting a kind of rebirthing process. Just to the west, the chapel of Osiris in Abydos contains a mural depicting the same ceremony in graphic terms, while in the adjacent Osirion—an underground temple made from cyclopean blocks of red granite—the Mysteries of birth and rebirth were also taught and conducted, and although the whole site lies five hundred miles southwest of Jerusalem, the Osirion and the Templars are linked.

Resurrection ritual. Abydos.

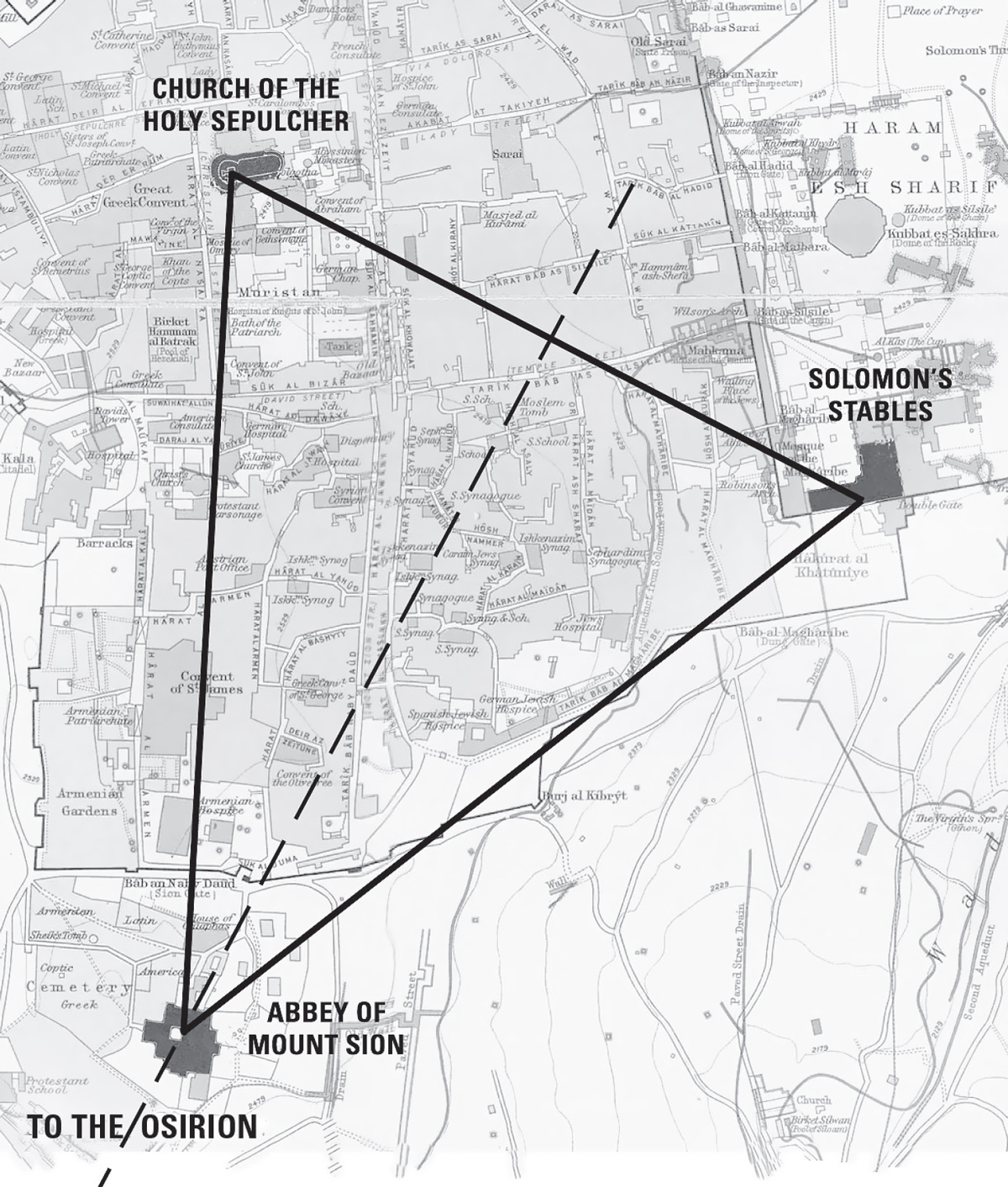

The prime Templar locations in Jerusalem are marked by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and Solomon’s stables, where the knights resided; the third is the Abbey de Notre Dame du Mont de Sion. The three sites form a perfect isosceles triangle, a symbolic holy trinity. When this triangle is bisected, an imaginary line extends all the way into the Osirion.

Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

The Osirion triangle.

Geodesy on a continental scale.

Likewise, the Essenes conducted their Mysteries teachings in underground chambers on Mount Sion, and after their church fell into a state of disrepair Godefroi de Bouillon made additions to the original floor plan in the form of the Chamber of Mysteries, which was supported on a foundation of eight pillars, a room where the initiate ate a meal prior to the living resurrection ritual, also known as the Last Supper.9 Godefroi therefore may have been maintaining a tradition upon which Sion is based, because the word sion is related to the Arabic sahi (ascend to the top), suggesting the location is interconnected with the process of “raising.”10 This Arabic interpretation is echoed in Jewish Kaballah, where the reference to Sion assumes an esoteric mantle as Tzion (a spiritual point from which all reality emerges).

Interior of the rotunda.

By far the most direct reference to Templar secret chambers lies in Gisors, France, whose own rotunda is indistinguishable from the one in Tomar. The Gisors structure sits atop a Neolithic mound on which the Romans built a temple. Beneath its floor, an extensive tunnel system links two nearby churches, one possessing an underground initiation chamber.11 Because such rooms are fundamental to the structural integrity of the building, they cannot be removed without making the structure above unsafe. It follows that if the Templars practiced the Mysteries in Portugal they must have built a similar chamber under the rotunda, and that chamber must still exist.

Alas, poverty and ignorance, the twin devils of conservation, have not been kind to the rotunda of Tomar. Details that would help the quest for a hidden chamber have been covered or replaced by well-intended attempts at preservation and, worse, by a lack of documentation. When its flagstone floor was refurbished in the mid-twentieth century no notes were made (at least none are known to have survived), nor were photographs taken of details that might appear out of the ordinary. If I had hoped to find a replica of the rectangular keystone with an iron ring and a staircase leading to an underground chamber, my quest was temporarily thwarted.

I retired to the adjacent courtyard and comforted myself with an orange freshly plucked from one of the four trees. Hope was in need of resuscitation. This was provided later that afternoon during a visit to the town archives, where a brief, yet tantalizing newspaper account from the 1940s describes how the exterior of the rotunda had been coated with reinforced concrete that hid or destroyed the entrance to what was then described as a kind of crypt.