45

PRESENT ERA. MONSANTO. AND OTHER PLACES FOR MUSING . . .

Bernard de Clairvaux was adamant that attention be paid first and foremost to a spiritual life and the mystical contemplation of the soul. It was this grace that led to enlightenment. One of the many positive virtues of the Cistercians was their focus on the common good, with the emphasis on fraternal charity and unity in the spirit of divine love. Much of this was achieved by adopting a submissive and charitable will.

The other was by frequenting sacred places, and Bernard’s exhortation to the Templars—to every knight, even—focuses on the importance of visiting and protecting the holy places, that they should not waste the opportunity to meditate on the deeper mysteries of life that unfold at these special locations.

It was with this advice in mind that he wrote a series of excellent meditations on positive experiences associated with personal transformation in ancient temples, particularly where avatars such as John the Baptist had demonstrated the virtue of love; in the Near East, emphasis was placed on the Holy Sepulcher as the symbol of resurrection that reveals the physical world to be a temporary stage for the transition of matter. In describing the spiritual significance of these sites, Bernard hoped the Templars would see their lives as a pilgrimage and that upon their visits they would look at sacred places with spiritual rather than material eyes.1

The overarching principle in the Cistercian ethos was the achievement of the sacred marriage between the soul and its source, a bond that launches a journey of self-discovery as a route to self-empowerment. By extension, this Cistercian ideal was also the driving force behind the Knights Templar. In this respect Bernard de Clairvaux was following a recipe that once kept ancient cultures in equilibrium for thousands of years, be they Tibetan, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, Sabean, Lusitanian, Bogomil, Cathar, or Celt. As Bernard wrote in De Laude Novae Militae, his letter in praise of the Knights Templar:

A new knighthood has appeared in the land of the Incarnation, a knighthood which fights a double battle, against adversaries of flesh and blood and against the spirit of evil. I do not think it a marvellous thing that these knights resist physical enemies with physical force, because that, I know, is not rare. But they take up arms with forces of the spirit against vices and demons and that I call not only marvellous but worthy of all the praise given to men of God . . . the knight who protects his soul with the armour of faith, as he covers his body with a coat of mail, is truly above fear and reproach. Doubly armed, he fears neither men nor demons.2

If Bernard de Clairvaux recognized immersion into sacred places as integral to personal transformation, he must have been equally aware of the mechanism at work in such locations.

A crucial component in the enactment of the Mysteries, particularly the component dealing with the “raising of the dead,” was the strategic placement of the temple. Like the Cistercians, who regularly chose areas that veered from architectural norm, the Templars also took great care in deciding the locations of their chapter houses and preceptories, as though they were sourcing a subtle element in the land.3 Without doubt they chose locations, especially in Portugal, that were richly associated with ancient traditions, particularly pre-Christian cults who honored the Earth mother Ceres, the Divine Virgin, Inanna, and Isis. The province covering most of Portugal in their time—and coincidentally the exact area donated to the Templars—was named after the goddess of Celtic creation myths, Beira. She appears in Scotland (another major Templar stronghold) as Cailleach Bheur, goddess of winter and the mother of the gods, the name nowadays simplified as Beira.4

The same applies to the Templar’s final home, Tomar, the old Nabancia. The name derives from Nabia, Lusitanian goddess of water and rivers. The body of water most associated with her cult was the one river (Neiva) honored by the people of Braga and Fonte Arcada, coincidentally the first two Templar homes in Portugale, and obviously, the river Nabão in Tomar itself. This specific attraction by the Templars to the sanctity and purity of water harmonizes with John the Baptist’s teachings on the importance of ritual bathing and baptism.

The second attention the Templars paid to location was the siting beside or on top of ancient places of veneration. The preceptories at Paris, Gisors, and London, for example, were built on Roman chapels above earlier Druid temples, even Neolithic stone circles. They followed the same practice in Portugal, as their chosen sites show:

- Loures. Church dedicated to Notre Dame built on the ruins of an early Celtic temple.

- Ceras. Named after the goddess of fertility, site of an ancient temple honored by the Lusitanians.5

- Castelo de Bode. The “castle of the goat,” associated with the pagan cult of Proserpina, daughter of Ceres, whose ritual is associated with springtime, hence the root of the word proserpere, “to emerge,” with respect to the ripening of the seed.

- Souré. Site of former monastery built with reused stones from a former Visigothic temple.6

- Faria and Idanha-a-Nova. Both on Neolithic sacred sites.

- Idanha-a-Velha, Braga, and Almourol. On temples dedicated to Venus and Isis.7

- Pombal. On a pre–AD 200 chapel dedicated to the archangel Michael.8

- Monsaraz. Hub of a metropolis of megalithic monuments.

- Santa Maria de Feira. On the Lusitanian temple of Tueraeus-Lugo, and one of the earliest places taken by Afonso Henriques in 1128.

- Castelo Branco. Already venerated in Neolithic times; the Templars built a church dedicated to Notre Dame above an underground chamber.

The list is extensive.

Such locations have a second major theme in common: they are known to coincide with the crossing points of the Earth’s natural streams of electromagnetic energy, what the ancients referred to as spirit roads. Many of these places even mark gravitational anomalies,9 and all ancient sacred sites, without exception, are founded on such hotspots.10

Simply put, the Earth’s telluric current is a kind of life force, a blending of the intertwined forces of electricity and magnetism. As the anthropologist William Howells attempted to classify it, “It was the basic force of nature through which everything was done . . . [its] comparison with electricity, or physical energy, is here inescapable. [It] was believed to be indestructible, although it might be dissipated by improper practices. . . . It flowed continuously from one thing to another and, since the cosmos was built on a dualistic idea, it flowed through heavenly things to earthbound things, just as though from a positive to negative pole.”11

When NASA scientists discovered magnetic energy spiraling like tubes linking the Earth to the sun—even employing the metaphysical term portals12—they essentially validated the ancient master geomancers and temple builders who sourced these very same flux events on the land because they were all too aware of their connection to territories far and beyond the confines of this physical sphere. The image the ancients chose to represent this elusive telluric force was the serpent or dragon, and it became a culturally shared archetype describing the energy’s winding behavior along its earthly course.

The Egyptian Building Texts provide actual instructions for establishing a sacred space, the principal component being the “piercing of the snake,” which serves to root these currents to a desired spot.13 Typically, when a serpent motif is displayed in a temple it is an instruction that the telluric current passes through the site, it is the X that marks the spot.14 Neolithic temple builders did the same by placing standing stones wherever telluric currents flow. These monoliths sometimes depict a serpent wound around them; the standing stones of Portugal, the betilos (literally “house of God”), often have carved snakes rising from the bottom of these stone sentinels.

This serpent energy is a natural force that can be harnessed for all manner of beneficial purposes; in Chinese geomancy such dragons were never slain, rather their electrical energy was kept in the realm and utilized for all manner of shamanic purposes.15

In 1983 a comprehensive study was undertaken to validate the existence of this energy in sacred sites. Using a magnetometer, the Rollright stone circle in England became the test subject. It was discovered that telluric currents are drawn into the stone circle in a spiral pattern. The leading project scientist also noted how “the average intensity of the [geomagnetic] field within the circle was significantly lower than that measured outside, as if the stones acted as a shield.”16 Identical readings have been found at temples throughout Europe, Egypt, and India, where the Earth’s energy field appears to stretch around the sites like a protective membrane.17 Celebrated primordial mounds such as Saqqara, Karnak, Luxor, and the pyramids control the energy into an interior neutral zone in a manner that is beneficial to people. Identical energy hotspots exist in Gothic cathedrals such as Chartres.18

The idea that sacred places are encircled by a force field has been widely explored. Measurements reveal how the current running through the entrance of the sites is double the rate of the surrounding countryside, making them not just doorways but also entrances. The magnetic readings at temples die away at night to a far greater level than can be accounted for under natural circumstances, only to charge back at sunrise, with the ground current from the surrounding land attracted to the temple just as magnetic fluctuations within reach their maximum.19 The voltage and magnetic variations are related and follow the phenomenon known in physics as electric induction,20 leading to the realization that sacred places behave like concentrators of electromagnetic energy.21

Magnetomer image shows how telluric forces behave at the Rollright stone circle.

There is one more thing. Temples, including the more recent Gothic cathedrals, are typically sited at locations that have been in continuous use for millennia, and they are unique in the sense that a second anomaly occurs at these hotspots. Every dawn the Earth is subjected to a rise in the solar wind, which intensifies the planet’s geomagnetic field; at night this field weakens, then picks up at dawn, and the cycle repeats ad infinitum. But there are places on the ground where the geomagnetic field interacts with the telluric currents.22 This action generates a hotspot known to science as a conductivity discontinuity, and even though ancient people did not own magnetometers they were able to source this energy long before scientists built machines that proved them right. Hence the name given to such sensitives: sourcerers.

The Sioux call this energy skan, and when concentrated at sacred sites it is claimed to influence the mind and creativity, as well as elevate personal power in the form of spiritual attuning. In essence, the energy raises the body’s resonance. Constant contact with multiple power places builds up a kind of numinous state of mind, what Chinese Daoists describe as “awakening the Great Man within.”

This has a profound effect on the human body, which is now widely accepted as composed of particles of energy, a walking electromagnetic edifice sensitive to minute fluctuations in the local geomagnetic field. With electromagnetism playing such a pivotal role in temples, its influence on the body is immediate. And since blood flowing through the veins and arteries carries a fair amount of iron, magnetism will work on it like a magnet reorganizes iron filings sprinkled on a sheet on paper. The same is true of the brain. Substantial amounts of magnetite are found in brain tissue and the cerebral cortex, and under the right conditions, magnetic stimulation of the brain induces dreamlike states, even in waking consciousness.23

Lastly, and possibly most importantly, is the effect that telluric energies in temples may have on the pineal gland, a pine cone–shaped protuberance located near the center of the brain. Fluctuations in the geomagnetic field affect the production of chemicals made by the pineal, such as pinoline, which interacts with another neurochemical, seratonin, the end result being the creation of DMT, a hallucinogen. It is believed that this is the neurochemical trigger for the dream state—the hallucinogenic state of consciousness that allows information to be received. In an environment where geomagnetic field intensity is decreased, people are known to experience psychic and shamanic states.24

This blending of modern science with ancient esoteric practices and beliefs helps explain why temples are built where they are and why the Templars and Cistercians followed the same formula by regularly erecting their sites in places that were either architecturally unsuitable or atop preexisting places of veneration.

It is perfectly feasible that such information was part of the knowledge decoded by the Kabalists working in Troyes. This spiritual technology was a component of the Mysteries teachings, whose central pillar concerned shamanic and ecstatic practices that led to a personal experience of God, in a nonreligious sense, and the strategic placement of the temple plus its geometry facilitated the process.

One of these hotspots is Jerusalem, one of the many so-called primordial mounds throughout the ancient world. In the time of the pharaoh Akhenaten it was known as Garesalem, which breaks down as gar (stone), esa (Isis), and salem or shalem (perfect). Thus, Jerusalem is “the stone that embodies the perfection of Isis”; it is a place of reconnection with the essence of the Divine Virgin.

Interestingly, telluric currents tend to be attracted to water, and water is a prerequisite in establishing a sacred site, quite beyond the obvious need for human sustenance. The place where John the Baptist performed baptisms, Bethany, was marked by a sacred mound where four springs intersect, thereby reflecting Bethany’s other name, Bethabara (House of the Crossing).

The same crossing is evidenced at Monsanto, where the two enigmatic arches inside its shaft mark the exact crossing point of two telluric currents.

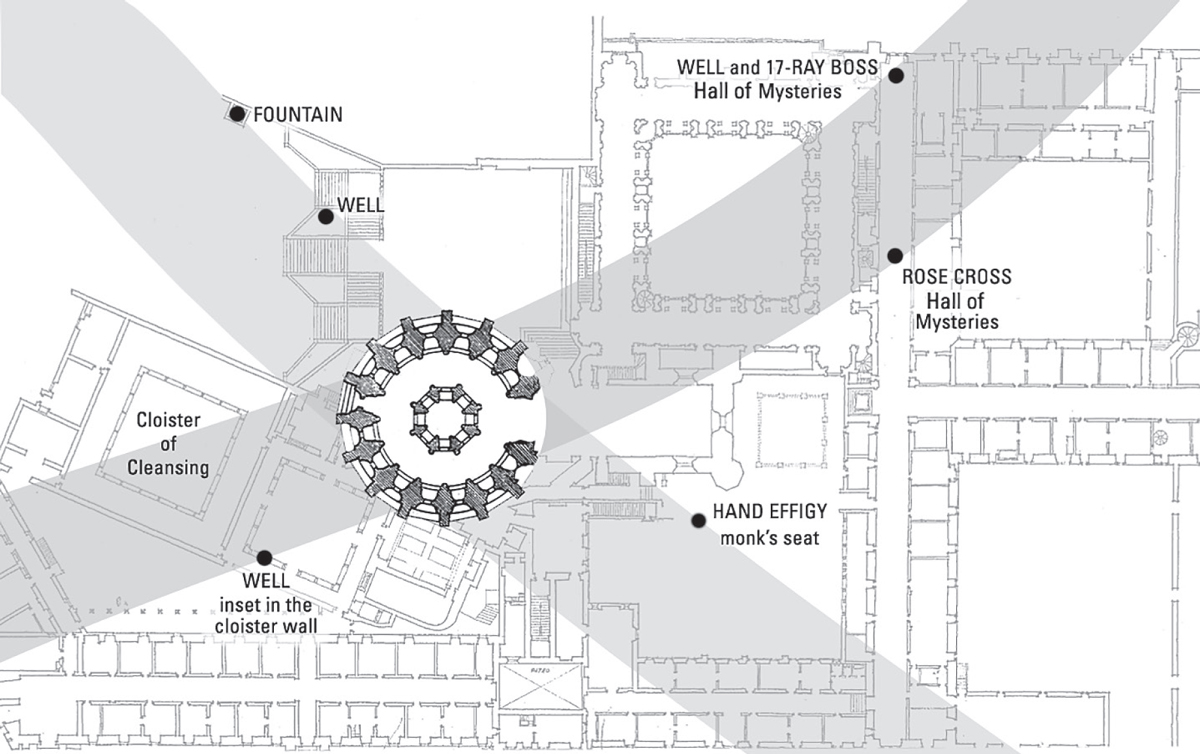

An identical situation exists under the rotunda of Tomar. The site marks the crossing of four underground water courses, while the diameter of the building itself defines the precise width of two crossing telluric currents. Several indicators marking the path of this earth energy still exist in adjacent cloisters and chambers. One is an effigy carved on a low wall that is used as a seat for meditating monks, resembling a hand pointing downward or, seen another way, an energy descending from the sky; two capitals depicting the Green Man in the underground hall of Mysteries (the alleged wine cellar) mark another edge of the current, as does its underground shaft and the seventeen-rayed boss strategically placed above it.

And yet Tomar is not alone when it comes to the Templars sourcing this exotic energy. Geomagnetic anomalies around sacred places in Portugal have been observed since the seventeenth century, and in recent times Portugal’s National Geological Survey found three major concentrations of magnetism in the Iberian Peninsula: the area of megaliths around the city of Évora, the promontory of Sagres, and the mountain of Sintra.25 Coincidentally, all three were prime Templar locations.

Relationship between telluric currents and the position of the rotunda of Tomar. Several surviving features mark the edges of these pathways, including the monk’s seat with its carved effigy.

Évora, a center of the cult of Isis-Diana, became the home of the affiliated Templar Order of the Knights of São Bento de Avis, created in 1162 at the Council of Coimbra, when the Cistercian Rule came into effect in Portugal.26 Its first Grand Master was Pedro, brother of King Afonso Henriques.

Sagres, already described in the time of the scholar Strabo as the Sacred Promontory and home to a group of dolmens,27 later become the focal point of the Templars’ maritime exploits under Henry the Navigator. What no one can explain to this day is what the Templars were doing with a curious three-hundred-foot-wide wheel made of radial lines of stones, the purpose of which is a complete mystery; beside it they erected a chapel dedicated to Notre Dame, designed with an octagonal roof and perfectly located at the intersection of two telluric currents.

As for Sintra, this was the village donated by Afonso Henriques to Gualdino Paes in absentia. It was the only such donation of its kind, which makes this unique offering all the more intriguing.

Sagres. The asymmetric radial structure left behind by the Templars.

Castle of Sintra.