47

PRESENT ERA. SINTRA. IN THE FOREST OF ANGELS . . .

Article 7. “Build in your houses meeting places that are large and hidden that can be accessed by underground tunnels so that the brothers can go to meetings without the risk of getting into trouble. . . . In the houses of unelected Brothers, it is prohibited to conduct certain materials pertaining to the philosophical sciences, or the transmutation of base metals into gold and silver. This shall only be undertaken in secret and hidden places.1

Talk about a smoking gun! This instruction to the Brothers of the Temple comes from a document listing the two secret Rules of the Knights Templar—the Rule of the Elected Brothers and the Rule of the Brothers Consulate. It was originally found in the possession of Templar Master Roncelin de Fos2 and rediscovered by accident in the Vatican archives by a Danish bishop. It unequivocally proves that the Templars followed a tradition of using crypts for the strict use of initiation into the Mysteries, intensifying the words of the Templar Preceptor Gervais de Beauvais to the Inquisition of how “there exists in the Order a law so extraordinary on which such a secret should be kept, that any knight would prefer his head cut off rather than reveal it to anyone.”3

A copy of these Rules was preserved by Brother Mathieu de Tramlay until 1205, then passed to Robert de Samfort, proxy of the Temple in England, in 1240, and finally to Master Roncelin de Fos. They were kept only by the inner brotherhood, forbidden “to be kept by the brothers, because the squires found them once and read them, and disclosed them to secular men, which could have been harmful to our Order.”4 The document describes how only true initiates of the Order knew of a secret that “remains hidden from the children of the New Babylon,” even the king of France, and that no prince or high priest of the time knew the truth: “If they had known it, they would not have worshiped the wooden cross and burned those who possessed the true spirit of the true Christ.” This truth alludes to a transformation of the soul and the establishment of a kingdom united and presided over only by God.5

Article 18, in particular, reveals much about the content of the Mysteries the Templars found and how, like the Essenes, this knowledge was revealed only to a select few: “The neophyte will be taken to the archives where he will be taught the mysteries of the divine science, of God, of infant Jesus, of the true Bafomet, of the New Babylon, of the nature of things, of eternal life as well as the secret science, the Great Philosophy, Abraxas [the Source of everything] and the talismans—all things that must be carefully hidden from ecclesiastics admitted to the Order.”6

One of the extensive articles illustrates the universal appeal of the brotherhood to ordinary people: “Know that God sees no differences between people, Christians, Saracens, Jews, Greeks, Romans, French, Bulgarians [referring to the Bogomils] because every man who prays to God is saved.”7 This utopian vision clearly undermined the religious authority of the Catholic Church and its stated doctrine that “outside the church there can be no salvation.” But to a medieval populace whose daily diet consisted of perpetual war, an economy based on plunder, and religious intolerance and corruption, the ethos expounded by the Templars must have seemed like honey cascading from heaven.

Such utopian thinking would have been perfectly at home in Sintra. Throughout this bucolic hill there is no shortage of immersions and disappearances into empyrean worlds. Two local legends speak of Templar knights falling in love with enchanted Moorish princesses shortly before vanishing through secret doors into the bowels of the mountain; another describes the Cave of the Fairy,*43 “formed by a large granite rock balanced on two rocks. Legend has it that every night a fairy will mourn her fate there.”8 This Neolithic passage chamber stands near another place of immersion called Anta do Monge (Dolmen of the Monk); anta†5 means “to mark,” it describes how such man-made monolithic structures deliberately reference hot spots whose energy differs from the surrounding land.9 Its association with a monk comes from a local legend of a Capuchin brother who became lost in one of Sintra’s famous mists and took refuge inside the stone chamber only to suddenly find himself “in another world.”

One reason why the memory of magic persists in Sintra is due to its consecration to lunar and chthonic cults since at least the Mesolithic era. Throughout this verdant mountain lie steps carved out of cyclopean granite boulders as though made for giants. There are Neolithic dolmens, caves for initiates and reclusive monks, and serene old hermitages draped in fern and moss. Sintra is, to quote Byron, a “glorious Eden,” and he ought to know; the poet overstayed his vacation there by three years precisely because Sintra is as close to paradise as one will get while alive.

In remote times the region was known as Promontorio Ofiússa (Promontory of the Serpent), its residents being the Ofiússa (People of the Serpent).10 The name has nothing to do with the physical worship of snakes and all to do with the honoring of the profusion of earth energies that were later proven to congregate in this area.11 The local Celts associated the mountain with Chyntia, the lunar goddess, from whom Sintra derives its name.12 Since the prefix sin is Babylonian for moon, it links Sintra with Sinai (Mountain of the Moon), where Moses once watched a pillar of light descend from heaven and offer a treasure of words carved on stone tablets. Hence, to be “a sinner” is to worship the moon along with its feminine connotations.

Steps leading to the Cave of the Monk. Such places of veneration and introspection have attracted chthonic cults to Sintra since at least 5000 BC.

One of Sintra’s oldest known prehistoric temples dedicated to the moon dates to at least 4000 BC. It is located on one of its many peaks, and various megaliths still lie scattered there. Beside it stands a temple*44 of unknown origin whose columns survived into the nineteenth century; a few yards away, Santa Eufemia church marks the spot where a sacred spring was virtuous even in the twelfth century,13 its water considered miraculous for curing “scabies of the liver and of other deformations of the body,” and was still thus in 1787.14

When the Greeks ventured here they regarded Sintra as Mons Sacer (Sacred Mount),15 and they amplified the tradition by building at least one temple dedicated to Militha, goddess of the moon.†6 The hermitage of Melides was subsequently erected on its ruins.

Thus, Sintra has been a veritable refuge for seekers of a terrestrial paradise, a sacred mount for reflecting on the bigger mysteries of life. Seekers such as the inner brotherhood of the Knights Templar.

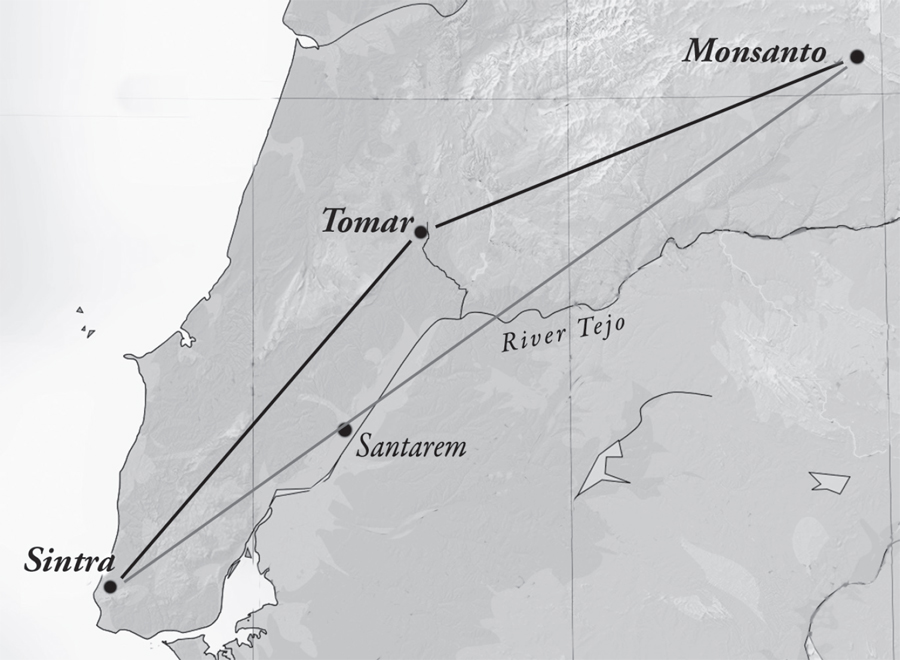

Centuries of well-intended restorations in Tomar may have left few, yet undeniable signs of the knowledge the Templars brought back from the Holy Land, but Sintra is an entirely different matter. Secret societies understandably do not openly advertise their wares, yet vestiges of the Templar’s craft remain scattered all around this area, and in one property in particular. And since this property lies precisely the same distance from the rotunda of Tomar as does the ritual center on the summit of that other sacred mount, Monsanto, such deliberate triangular referencing was all too tempting to ignore.

Equidistant geodetic placement of Templar sites on Sintra, Tomar, and Monsanto.

The Templar homes around the main square in Sintra were adjacent to the former Arabic palace, whose entire ground floor the knights rebuilt.16 Hundreds of years of earthquakes, neglect, and time made their mark on the properties, but their original foundations remain and now serve modern-day businesses, such as the Hotel Central and Café Paris.*45 In 1970, a hypogeum, or ritual chamber, with access tunnels was discovered beneath said café, with a connecting passageway leading one way to the nearby palace and the other uphill toward the castle; another was found behind the Café da Avozinha.17 It seems espresso and secret Templar places are magnetically drawn to each other.

In 1904 Sintra attracted one notable figure to its womb as though by magical impulse, a rich merchant named Carvalho Monteiro, who bought a large sylvan estate named Regaleira. Barely ten minutes’ walk from the village’s central square, the property’s extensive reputation must have sparked his interest, for its status as a sacred place was known as far back as 1717, when reference is made to a via sacra running through the estate, which back then was known as Quinta da Torre (Estate of the Tower).*4618 Even when Afonso Henriques and the Templars rode in, a sacred spring was known to exist there, its waters so efficacious they caused one eyewitness to write, “The use of which is said to stop coughs and ally consumption. Hence, if the inhabitants should hear anyone coughing, they might discern that he was not a native.”19 The resident Arabs discovered these healing properties for themselves, even noting how many of the local rocks possessed medicinal benefits, especially for curing kidney ailments.

The estate produced an abundance of fruit and other staples, but by 1904 the owners had fallen on hard times, and so Quinta da Regaleira, as it became known, was auctioned and Carvalho Monteiro was the winning bidder. He was a man of prodigious culture, with a degree in law from the University of Coimbra. He was also a Freemason, and as coincidence would have it, he followed a long tradition of Freemasons who had previously owned the property: the brother of the former owner in 1840 was a Freemason, while the owner before her, Manuel Bernardo, was both a Freemason and a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences.

An absence of paperwork then bridges the history of the estate between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, but given how Freemasonry is the progeny of the Knights Templar,20 habits would indicate the property most likely remained “in the family” throughout those centuries. And once one realizes what exists on the property it is not hard to see why.

Monteiro made sizeable improvements to the estate, and judging by the symbolism employed throughout the villa he built, the chapel he erected, and the gardens he refurbished, every inch was designed to be an open invitation for immersion into the Mysteries. Masquerading as a scene from a divine opera, each corner and alcove of Regaleira is filled with alchemical and sacred symbolism. It is a complex environment of sacred spaces and mythical and magical talismans, with grottoes, towers, and temples set in a scenographic landscape that leads a pilgrim deep into contemplation of hermetic knowledge.

Carvalho Monteiro was a stout man, a doyen of perfect health, so clearly he did not move here to imbibe the miraculous waters. The images, themes, and emblems in Regaleira follow the themes throughout Tomar’s Convent of Christ, their placement throughout the estate reflecting a profound philosophical and esoteric wisdom. Upon his death, his prodigious collection of books was bought by America’s Library of Congress.

Near his villa stands a compact, rectangular chapel resembling a white castle in miniature, brimming with Templar, Hospitaller, and Masonic symbolism, including a haloed triangle with a central eye above the entrance—the all-seeing eye of God. An imposing Templar cross made from tiny colored tiles commands the floor of the chapel; in the gallery above, several more Templar crosses are interspersed with the cross of the Monteiro family. A narrow and intricately carved limestone spiral staircase descends into a basement whose marble floor is covered from wall to wall in a checkerboard pattern, the eternal play between light and dark, good and evil, emblem of the Knights Templar and, later, the Freemasons. A second staircase leads farther down into a deeper subterranean recess connecting a labyrinth of tunnels that burrow deep into the side of the mountain.

After eventually reemerging into the light of day behind a statue of the Divine Virgin, a cursory look at the rear of the chapel reveals a subtle sculpture depicting a castle with two towers—the castle of Mary and Martha, to whom the Templars pledged allegiance, resting on an effigy of the Green Man.

The white chapel.

Chapel interior. Mosaic floor featuring the later Portuguese Templar cross over the armillary sphere, symbol of the Templar’s maritime exploration.

The castle of Mary and Martha, symbol of the Magdalene, to whom the Knights Templar pledged allegiance; it stands over a Green Man, tutelary spirit of nature.

Being a mere seven miles from my place of birth, I have visited this property numerous times, sometimes on consecutive days, and each time a new wonder presents itself. Since one of the focal points of my investigation centers on the reason behind the Templar’s presence in Portugal, my attention was drawn to a dolmen-like structure farther up the hill, which is reached after ascending the meandering garden paths filled with statues of solar and lunar deities, a reflecting pool for stargazing, and a grotto protected by two enormous dragons. Finally, the monoliths appear, heavily encrusted with soft, damp moss.

At first, there appears to be no door, but closer inspection reveals a seven-foot-tall stone slab, and with a little effort, the slab pivots to allow passage through the upright stones. Inside, one is confronted with the remarkable sight of an eighty-foot well circumscribed by an arched spiral staircase.

Entrance to the initiatory well disguised as a Neolithic stone chamber.

The concealed entrance into the top of an initiation well.

The bottom of the shaft sits in the half-light reflected from the diffused sunlight drifting through the trees above, but the symbol on the marble floor is unmistakable, a combination of the heraldic emblem of the Monteiro family and the cross of the Knights Templar.

After a reality check, I took a compass reading of the doorway through the megalith. It faces west, in esoteric tradition the direction the initiate follows during the final ritual of living resurrection. Ritual descent is traditionally made clockwise, and indeed the paved staircase descends just so. The builder knew what he was doing. One-third of the way down, a tunnel carved out of the limestone burrows through the hill, at the end of which appear two dragons guarding the entrance into daylight. I retraced my steps and continued my descent; the Templar cross below was by now glistening from the beads of falling drizzle. At the bottom, another carved doorway marked a further passage into the unknown, and a journey into a labyrinth of tunnels ensued. Cut into the limestone and granite, several passageways of indeterminable age branch in several directions; in some places it is clear the passages have been blocked, and beyond lies a network of tunnels still unexplored.

Some niches and chambers are large enough to accommodate someone wishing to spend time in a hermitlike solitary environment, contemplating the Mysteries in total sensory deprivation, meditating in the peace and quiet and darkness of the womb to the point where the ego is dissolved and only the soul remains. It is a favored alchemical method by which incalculable numbers of adepts through the ages have experienced personal revelation.

Immersion complete, one continues wandering the maze of tunnels, each decorated with chunks of coralline limestone imported from the coast and glued by hand to the walls, eventually to emerge under a waterfall as though engaging in a kind of baptism, and finally, out into the light. To make the point that the experience was designed to be both initiatory as well as symbolic, a pond stands between you and solid ground, and only after carefully negotiating a set of stones barely concealed below the level of the water does one reach the other side.

The first well.

Part of the endless subterranean passageways at Regaleira that burrow deep inside the mountain of Sintra.

Walking on water. Point taken.

Clearly, the well was never designed to hold water. It is a ritual well, a component of a deliberately designed ritual landscape. But a ritual landscape created by an early-twentieth-century merchant is no proof the Templars were here or that they engaged in similar practices. Or were they?

A stupendous feat of construction it may be, but the architecture of the well of Regaleira is incongruous with the rest of the estate. While the structures throughout were built in the romantic revivalist Manueline style common to Carvalho Monteiro’s time, the well is Romanesque, the general style in the era of the Templars. However, the condition of the structure does not suggest it is eight hundred years of age either. There is no doubt restorations have taken place. The Romanesque arches are not dissimilar in style to early-twentieth-century reproductions, and the level, unworn steps and mosaic well floor also appear to be recent. But once again, something just did not add up.

While I wondered and wandered the maze of tunnels, I took a right turn into one unlit section and, confined within its obsidian darkness, finally discovered a practical use for my iPhone—a flashlight. After bumping my head and shoulders here and there, a faint glow of gray light penetrated the black beyond. I emerged at the bottom of a second shaft and inside another mystery.

Unlike the previous “well,” this second shaft was primitive of construction. Five levels of unevenly stacked and undressed limestone blocks, here and there patched and repaired. Behind the blocks hid five low and narrow circular galleries, each accessed through claustrophobic spiral stairs set into the rough wall and in a measured style that suggests a later refurbishment. The top of the shaft is literally an eighteen-foot-diameter hole, level with the ground and surrounded by a rough, drystone wall in the shape of a horseshoe.

The architectural style of this shaft could not be more removed from the first; in fact, its style of construction has more in common with habitations found nearby at Castro de Ovil dating to circa 100 BC.

Despite an abundance of architect’s drawings for the entire estate, including the features found throughout the gardens, not a single blueprint exists for either of the “wells.”

The following day was spent in Sintra’s archival offices, which for a small town are surprisingly well maintained; some of its original records date back to the time Afonso Henriques rode through town with his Templars. The sheer scale of manual labor performed at Regaleira would have left a paper trail; it was impossible for it not to. It was this researcher’s dream and the town archivist’s nightmare when I placed a request for every available scrap of paper and bill of sale between the arrival of writing and Monteiro’s time, and the folders just kept coming. Somewhere: an impressive newspaper report, a bill of sale for large quantities of building material, dynamite, horses, hired labor—anything that would link the wells to the early-twentieth-century merchant.

Nothing. No evidence exists that Carvalho Monteiro built either one. More architect’s drawings materialized; not one showed a well or a shaft. Two possibilities now presented themselves. First, if the wells were indeed part of secret initiations into the Mysteries, then obviously their existence would have been a matter of discretion. And yet once Monteiro’s work at Regaleira was complete the property was opened to the public, rendering all secrecy redundant. A second possibility is that the shafts, or at the very least the more primitive of the two, were already on the property before Monteiro’s time. Monteiro bought Regaleira in a state of disrepair; unquestionably, he made immense contributions and improvements to the site, and yet by the same token he may also have restored a portion of whatever was already on the property.

The available evidence and the circumstances surrounding the provenance of the property favor the latter argument, and local researchers have independently reached the same conclusion: “It is not known for certain, but it is probable that both the large and small wells already existed before the acquisition of the property by Carvalho Monteiro.”21 Regaleira’s previous owners were also Freemasons, and by 1830 the estate was already well developed. Freemasons and their Templar precursors share a history of close bonds and family ties, it would be inconceivable for the property to have been sold to “outsiders” between the last recorded Templar owners in 137122 and its documented use as a sacred ceremonial route three centuries later. And there’s the rub: the property was spiritually significant even before the day Afonso Henriques rediscovered it. After all, there must have been a very good reason why it once was named the Forest of Angels.

The second well.

One of two megalithic passage chambers at either end of Sintra. They are aligned to the equinox sunrise and sunset, respectively, the ritual directions used in resurrection rituals across the world. Both structures essentially form portals on the east and west sides of the mountain.

Evidence that the Templars realized its spiritual significance lies in the anomalous donation of Sintra by the king to Master Gualdino Paes in absentia. No one could have guaranteed Paes’s safe return from Jerusalem; for all he knew, Afonso Henriques could have been awarding the property to a dead man, and yet he followed through on the certainty of his conviction. Could it be that Afonso—an initiate of the inner brotherhood himself—awarded Regaleira to the person most likely to appreciate its sanctity, a man who went to the Holy Land, was initiated into the Mysteries, and shone “as a star”?

Two things are certain about the second, primitive “well.” One, the horseshoe entrance faces northeast, the summer solstice sunrise, the highest position of the light, the esoteric reference to ancient wisdom, and coincidentally, the feast day of John the Baptist. And two, the entire structure is so plain, so devoid of any decoration it is as though built by people for whom ornamentation was superfluous, a distraction from the total experience of God—as though the architect had not been a twentieth-century Manueline revivalist but a Cistercian monk.