49

1153. GOSSIP IN THE ALLEYWAYS OF JERUSALEM . . .

Stories of the existence of an Ethiopian ruler named Presbyter John had been circulating around the city for eight years now. Gualdino Paes, recently arrived from Portugal to join the newly appointed Templar Grand Master, André de Montbard, would have been privy to these rumors, even though he would return to his native land by the time envoys representing this king finally arrived to request an altar in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher from the patriarch of Jerusalem.

Seeing as the Ethiopian king was “a direct descendant of the Magi, who are mentioned in the Gospel,”1 and one of the leaders of that sect had been grandfather to Mary Magdalene, the request was granted in 1177.2 Pilgrims describe the monks and priests in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher at the time as Copts, Egyptian Christians from the city of Alexandria.

A century passes and the story picks up in Bavaria when a writer by the name of Albrech von Scharfenberg adds the final component to the Graal legend originally begun by Chrétien de Troyes. In it, he mentions the final resting place of the Ark as the land of a priest-king nicknamed Prester John. Although that kingdom is eventually identified as Ethiopia, never did the Ethiopians refer to their king by that name. “Prester John” was an unfortunate artifact of translation, Prester being a contraction of the Latin pretiosus (exalted), while John was in actual fact pronounced gyam, which in Ethiopian means “powerful.”3

Ethiopia had a long tradition of black female monarchs who were often referred to as Virgin Queens. They ruled a vast empire stretching along the Nile, through Egypt and all the way to the Mediterranean, covering parts of Eritrea, Nubia, Yemen, and southern Arabia. It was a province considered as large as India, so much so that cartographers often confused the two.4 The focal center of the kingdom was Meroe, an ancient city on the eastern bank of the Nile centered on an area presided by no less than two hundred pyramids.

Meroe inevitably brings up connotations with Merovingian, the holy bloodline of Trojan kings and the line of Kings David and Solomon, which reemerged in central Europe around the fifth century AD with Merovech, king of the Franks, whose territory included the duchy of Burgundy. The focal point of these connections is Solomon and his lover, the queen of Sheba.

The queen of Sheba bore the title Maqueda, or as it appears in the Middle East, Magda, as in Magdalene. The attribute translates as “magnificent one.” In Arabian, Sheba is Saba, and may be linguistically linked to the Sabeans, the gnostic sect who once migrated from Ethiopia around 690 BC.5 In Ethiopian history, this consort of King Solomon was addressed as Negesta Sabia, with the word sabia surviving intact in the Portuguese language and meaning “a wise woman.”

The curiosity of the Knights Templar led them to trace the resting place of the Ark of the Covenant to the queen of Sheba’s former kingdom,6 because around 1181 Emperor Lalibela of Ethiopia is said to have given them permission to build round churches in his land. This they did, and they progressed to create eleven others carved entirely out of the volcanic bedrock, one of them in the shape of a Templar cross. An eyewitness account describes how some of the churches “hide in the open mouths of huge quarried caves. Connecting them all is a complex and bewildering labyrinth of tunnels and narrow passageways with offset crypts, grottoes and galleries . . . a subterranean world, shaded and damp, silent but for the faint echoes of distant footfalls as priests and deacons go about their timeless business.”7

That Emperor Lalibela was somehow involved with a holy bloodline lies in the nature of his name, which literally translates as “the bees recognize his sovereignty,” the bee being the adopted symbol of Merovingians through the centuries.8 Like other Ethiopian monarchs, Lalibela also held the title Neguse Tsion (King of Sion); thus, he may have been involved with the Ordre of Sion in Jerusalem, given its original relationship with the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

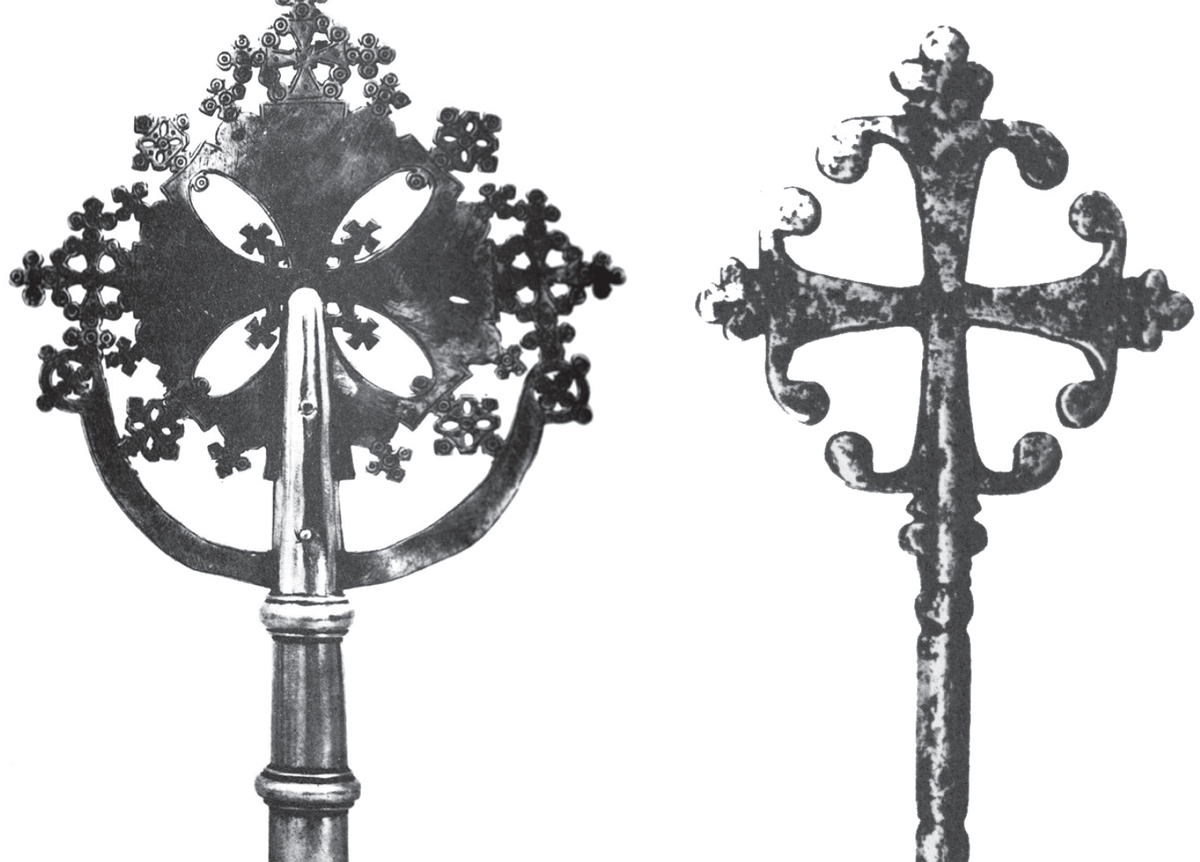

Three and one-half centuries passes, and the story picks up again in the sixteenth century, when unusual processional staffs are witnessed in Ethiopia’s Coptic Christian community. One comprises a large central cross identical in design to the first dynasty Portuguese Templar cross, while the other bears the unmistakable emblem of the Templar cross surmounted with the fleur-de-lys, emblem of the Portuguese Order of Avis, the splinter Templar group created by Afonso Henriques, whose leader was the king’s brother, Dom Pedro.9

Left, first dynasty Portuguese Templar cross, and right, cross of the Order of Avis, atop Ethiopian processional staffs.

All this is most odd. How did the Portuguese Templars become involved in remote Ethiopia, especially since the entire Order had supposedly been extinguished two centuries earlier throughout Europe by order of the pope?