EPILOGUE

LUSITANIA. WHERE KNOWLEDGE IS STORED, GUARDED BY A GODDESS WHOSE SYMBOL IS A TRIANGLE . . .

Just how wide did the Templar plan in Portugal extend? Consider the following connections . . .

In her grant of 1139, Eleanor of Aquitaine gave the Knights Templar a building and a mill in the western French port town of La Rochelle, “entirely free and quit of all custom, infraction, and tolte and taille [levies] and the violence of all officials, except for our toll.” She suggested her vassals make similar donations. More importantly, she granted the Templars freedom to transport anything through her lands “freely and securely without all customs and all exactions.”1

Almost two hundred years later, this foresight would save the lives of countless knights and ensure the survival of the Order of the Temple beyond the borders of France and the grasp of Pope Clement V. That was the eve of Friday, October 13, 1307. A statement by a Templar named Jean de Chalon declares that three carts containing the Templar treasure (gold and documents) left the Paris temple that evening following a tip-off that the king’s henchmen were out to arrest all members of the Order. The intent was to move the contents of their preceptory to La Rochelle, where the Templars owned a fleet of large ships for the ferrying of passengers and cargo between Europe and the Mediterranean. However, by the time the carts reached the Templar castle at Gisors the roads were already under surveillance, so the contents were hidden in subterranean passages under the castle’s keep.

The statement was obtained under torture and may have been a red herring. Nevertheless, a document associating Gisors with the Templar treasure was found in the Vatican library and obtained at the request of the French ambassador to Rome.2

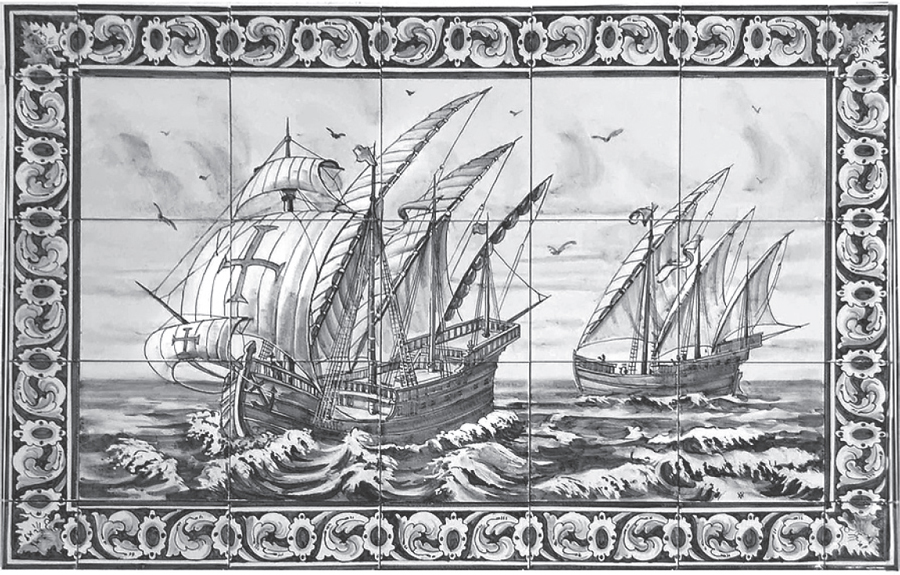

Eighteen ships filled up with fleeing Templars at La Rochelle while other knights made their way down the Seine (a river from which they were exempt from tolls and thus not subject to search) to the port of Le Havre. Once loaded, the ships sailed into the Bay of Biscay and disappeared from all documented history. It is a notable omission given how such a considerable fleet would have been of significant value.

In truth the fleet split into two. One arm sailed west to Portugal,3 making good use of the water routes made available since the days of 1125 when the Templars used the estuary of the Mondego to reach the castle of Souré.4 Upon reaching Portugal, to ensure anonymity, they disembarked at a small fishing village on a peninsula near Serra d’El Rei. Some of the ships’ names were Temple Rose, Great Adventure, and Falcon of the Temple (a salute to the god Horus, son of the resurrected Osiris).5 It is rumored that part of a treasure was offloaded here and transported to nearby Obidos, a town patronized by the queens of Portugal.6 The remaining ships and their cargo continued down the coast to Lisbon. The river Tejo was navigable in those days all the way to Spain, as were many of its tributaries, one being the Nabão, which leads right onto the quay opposite the Arab waterwheel in Tomar.

Meanwhile, the second fleet sailed north to Scottish Templar strongholds in Kilmartin, Kilmory, and Castle Sweet. Essentially, the Templars took up positions on the extreme points of Europe, from which the only rational place to expand was across the Atlantic.

Framing the sunrise side of the town square of Tomar, the church of John the Baptist looks out over a pavement of large black-and-white checkerboard mosaics made of small cobblestones, as though the entire plaza is the center of a Masonic stage. And yet the play is real enough, for it was from here that the Knights Templar—as the rebranded Order of Christ—set out on bold maritime explorations that changed the world as we know it. This great work was conducted patiently and over the course of centuries, initially with the building of Europe’s first independent nation-state, then a kingdom within the kingdom of Portugal, and following the disbandment of the Order throughout Europe, a cooperation with brothers taking refuge in Scotland to resume an ongoing mission.

Like all esoteric sects, the Templars were master geometers. If we recall, an axis runs through the rotunda, through two marked pillars in the church of John the Baptist, continuing as the crow flies to the abbey on Mount Sion. Could the Templars have applied the talisman of triangular geometry to a third notable landmark to form a geometric trinity?

A number of shared similarities exist between events in Portugal and Scotland: the protection offered the Templars by King Dinis was similarly offered by his counterpart, King Robert the Bruce, who never legally ratified the dissolution of the Scottish temple;7 both countries’ move toward independence occurred in battles on the feast day of John the Baptist;8 the Templars in Portugal were renamed Order of Christ, and in Scotland, Scottish Rite Freemasonry. On the infamous night of October 13, Templar ships slipped out of French ports, split up, and sailed to these two respective safe havens.

Following the Council of Troyes in 1128, the Templars under Prince Afonso Henriques set in motion a chain of events that led to Portuguese independence. As this was unfolding, Hugues de Payns was in Scotland meeting with King David I, who granted the Grand Master the chapelry and manor of Balantrodach, a small hamlet whose name means “stead of the warrior.” The land around Balantrodach had earlier been awarded as a gift of gratitude to William the Seemly, of the Sainte Clair family, for bravery and loyalty to the Scottish crown;9 his son Henri de Sainte Clair played an active role in the first Crusade and the conquest of Jerusalem by King Malcolm.10

The Sainte Clair family originated from Normandie, a county adjoining Flanders, the place of origin of a number of original Knights Templar; the Sainte Clairs were themselves linked by blood and marriage to the family of the Counts of Champagne and the Duke of Burgundy.11

Hugues de Payns set up a preceptory at Balantrodach in 1129, to which was added a church and a Cistercian cloister and mill.*50 In essence, it became a focal center of operations for the Templars in Scotland. Contact between Scotland and Flanders became very active thanks to the partnership between King David and the Flemish comte Philippe d’Alsace, cousin of the Templar knight Payen de Mont-Didier;12 the king also surrounded himself with Templars and appointed them as “Guardians of his morals by day and night.”

After the night of October 13, the Templars escaped to enclaves throughout Scotland, and in time amassed no less than 519 properties.13 They would have been fascinated to discover the Graal legends had become popular there too, not least because Celtic mythology is rife with quests by a group of chivalric warriors seeking a mysterious sacred object of mystifying power, along with a remote castle and a crippled king ruling over a land similarly fallen on hard times. In one of the original Graal stories—specifically the one written by Chrétien de Troyes—the Graal knights defend a castle guarding the gates “de Galvoie,” which is a specific reference to a real Scottish castle in Galloway, where the Bruce clan was seated after being made lords by King David I.14 Chrétien also makes a reference to a religious site at Mons Dolorosus, which at the time was the actual name of the Cistercian abbey of Melrose in Northumberland, where Robert the Bruce’s heart was buried.15

One hundred and fifty years go by, when in 1446, Earl William St. Clair†8 founds an unusual chapel just three miles from Balantrodach, at Roslin, and it shares a number of similarities with the rotunda of Tomar:

Both never originally housed an altar.‡2

Both were built adjacent to castles.

Both sit on promentories above fabled rivers.

Both sit over a warren of tunnels, those at Roslin accessed only by the lowering of a person down a well, much like the one inside Tomar’s Chamber of Mysteries.

Both are rumored to be the final repositories of the Templar treasure. (Roslin’s ships having sailed up the Esk,16 while Tomar’s used the Nabão.)

The obvious similarities end there, for while the original interior of the rotunda was as plain as a Cistercian, the same cannot be said of Roslin chapel, which can only be described as a coded esoteric library of stone housing the beliefs and traditions of the Knights Templar and just about every faith in the world.17 However, Roslin was founded at the same time Henry the Navigator was adding an apse to the rotunda of Tomar, a project later completed by King Manuel I, who also added a nave. From this point the similarities continue:

Both buildings make prominent features of the Widowed Mother and the Green Man.

Both feature a similar style of architecture, which in itself is not unusual given they share the same period, except that Roslin’s outstanding feature is a curved column called the Apprentice Pillar, the “model of this beautiful pillar having been sent from Rome, or some foreign place.”18

It is possible this “foreign place” may have been Tomar, because the anomalous pillar so closely matches the unique Manueline style in which its nave is built.

And here is where the geometrical connection with Tomar and Mount Sion comes in. One of the details that struck me from Warren’s excavations beneath Temple Mount is an anomaly he found on the northeast point of the sanctuary: “. . . a perforated stone. The uprights of the wall are formed by megaliths up to 14 ft tall and of extreme age.” More recent marks on the stone show a cross of the type used by early Christians. The stone that closes the end of the passage has “a recess cut into it four inches deep. Within this recess are three cylindrical holes arranged in the form of a triangle.”19

No explanation exists for this unusual feature. So let us assume for a moment the anomalous triangle suggests a triangulation of points or places, because if we link Mount Sion, Roslin, and Tomar, interesting commonalities emerge: all three places are associated with ancient wisdom: Jerusalem speaks for itself; Roslin, or ros linn (a name chosen by Henry St. Clair), translates from Gaelic as “ancient knowledge passed down the generations”;20 and Tomar means “a place of imbibing,” in the land of Lusitania, “the place where the knowledge is stored.”

It was ancient practice to locate temples sharing similar purposes according to perfect triangles,21 the triangle being a two-dimensional representation of the tetrahedron, the fundamental geometry of matter. Thus, by linking sacred places across sometimes-vast distances in perfect triangular relationships, it was believed the sites were imbued with the power of nature’s most elemental geometric form.22

The link between the rotunda of Tomar and the basilica of Notre Dame du Mont de Sion can now be extended to Roslin Chapel, and as such, the three temples form a perfect isosceles triangle, with a margin of error of just 0.1 percent.*51

Suddenly the triangular symbol of Tanit, a presiding goddess of Lusitania and Palestine, takes on a whole new perspective.

Sion, Switzerland.

When a mound was excavated in Suffolk, England, it was found to contain the sixth-century ritual burial of a ship along with a trove of gold coins belonging to the Merovingian family dynasty, one coin in particular linking the items to Theodebert II, a Merovingian king. The coins were minted in Sion, Switzerland.23

The diocese of Sion is the oldest in Switzerland, when in 999 the last king of Burgundy, Rudolph III, granted the county of Valais to its bishop, and Sion became the capital. At that time, a Carolingian church stood on a prominent mount above the village. After its destruction by fire it was rebuilt as a fortified church in the twelfth century and became the basilica of Notre Dame de Valere; as for the hill, it was dedicated to Saint Catherine, patron saint of the Knights Templar.

If a bearing is taken from the basilica of Mount Sion in Jerusalem to its counterpart in Sion, Switzerland, the line bisects the Tomar-Roslin-Sion triangle and extends across the Atlantic, making its first landfall in Newfoundland, by the city St. John’s, named after, you guessed it, John the Baptist. It then continues past the towns of St. Catherine’s, and St. Mary’s.

Henry St. Clair was the grandfather of the founder of Roslin Chapel. Inside this curious building there are stone carvings of North American plants supposedly not seen by Europeans until Columbus’s arrival in that part of the world. Since the chapel was completed in 1486 and Columbus made his first voyage six years later, common sense dictates that Henry St. Clair or members of his court made a voyage across the Atlantic first. Although stories and letters circulated at the end of the fourteenth century outlining such an expedition, the evidence has been hard to substantiate.24 However, there exists an anomalous round tower in what is today Newport, Rhode Island, in a style of architecture common to medieval Europe. Further inland, in Westford, Massachusetts, someone carved an effigy on a large boulder of a knight. He wears the habit of a military order, a sword with a pommeled hilt commensurate with the style used in the fourteenth century, and a shield depicting a single-masted medieval vessel sailing west toward a star. The style is virtually identical to carvings on grave-posts in the Templar cemetery in Kilmartin, Scotland, which date to the same period. Lending weight to the argument that Templar knights may have crossed the Atlantic are testimonies from the only two Templars arrested in Scotland, who stated how their brothers at Balantrodoch “threw off their habits” and fled “across the sea.”25 If so, they would have lived and died there, and a number of old gravestones in Nova Scotia (Latin for New Scotland) do incorporate Templar devices such as the skull and crossbones, the symbol of the Templar’s maritime fleet, just as they do on Scottish graves.26

It is speculated that the Scottish Templars shared information of this voyage with their Portuguese brethren and that the knowledge found its way to Columbus via Portuguese navigators in Lisbon. Certainly, Columbus solicited the sponsorship of the Portuguese court for an expedition to the Indies—even his father-in-law was a knight of the Order of Christ—but still the Portuguese king acquiesced to his request, possibly because the Portuguese, particularly Henry the Navigator, kept their maritime ventures close to their chests.

There is good support for this. There exists a long seafaring tradition between Genoa and the Portuguese monarchy, dating to as early as 1099 when Dom Henrique twice sailed to Palestine with the Genoese.27 The relationship was still strong two centuries later when shipbuilders and thirty sea captains were recruited from Genoa to rebuild the Portuguese fleet. Then in the early fifteenth century, the Portuguese ambassador Damião de Goes sailed to Italy to study in Padua, where he befriended the Italian cartographer Giovanni Ramusio; Goes was also the Commander of the Order of Christ, and he shared with Ramusio various Templar maritime discoveries, which the Italian illustrated in Raccolta di Navigationi et Viaggi. One of the maps in this opus shows the coast of Labrador dotted with Portuguese fishing boats and what appears to be the drying of salt cod, while the Portuguese shield and coat of arms feature prominently on this North American territory, suggesting these lands were already—and unofficially—known to the Portuguese crown.28

Which brings us to the carving of that knight, the ship, and the star. In his History of the Jews, Josephus points out how the Essenes placed the origin of good souls in an idyllic land in the West. They mention this again in the Copper Scrolls and associate this land with a star of the Orient; the same concept is found in the esoteric traditions of the Celts, Jews, and Greeks. West is the place of the setting sun, so to figuratively follow the path of the setting sun is to enter into the Otherworld, the place of spirit. The Mandeans—successors to the Essenes and Nasoreans—added that this land is identified by a star called Merika.

Since the Templars found the scrolls written by their forebears, it stands to reason they would set sail for this land of paradise after a mass arrest essentially undermined their power as a group. Ensconced in their safe harbors in Scotland and Portugal, the members of the Order of the Temple made future plans to go west.

In Templar symbology, Merika is the western star toward which mounted knights ride and ships sail. This star, often depicted in the form of the five-pointed pentagram synonymous with Isis, is also the bright morning star Sirius, otherwise known as Sophis, the star of wisdom. The same symbol appears above the altar of the Templar’s mother church in Tomar, the first structure obsessively built by Gualdino Paes, in a town created by the Templars that became the focal point of their overseas explorations.

The attribution of the name America to the newfound land in the West has long been wrongly attributed to the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci by a highly imaginative priest named Waldseemuller, who simply pieced together several unconnected facts and created an accidental myth.29 So by the time Columbus reached the “New World,” it was hardly so; Merika was already old news to the Templars.

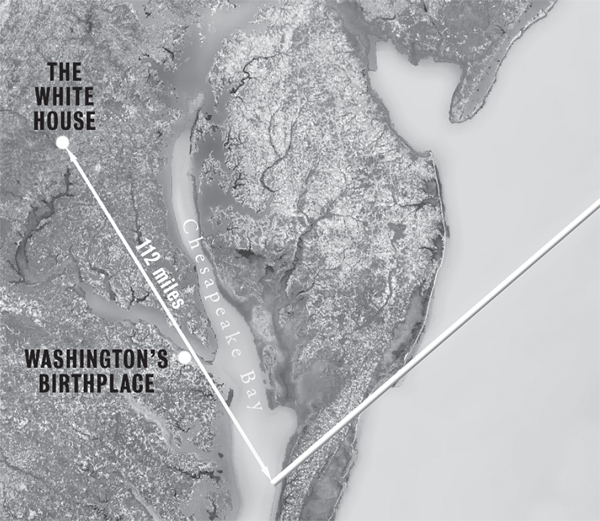

Whether by design or coincidence, the imaginary line from Mount Sion, through Sion, Switzerland, and St. John’s, Newfoundland, continues into Chesapeake Bay, near the birthplace of a Freemason by the name of George Washington, who laid the foundation stone for the White House on October 13, essentially commemorating the anniversary of the death of Portuguese Templar Master Gualdino Paes and, 112 years later, the day the Order of Temple was almost extinguished, along with its purpose.

It seems that, even at the very end, another chapter begins in the eternal quest to build that heavenly Jerusalem.

“Then he saw the rich Graal enter through a door to serve the food; it promptly put the bread down in front of the knights.”

—CHRÉTIEN DE TROYES, PERCEVAL, THE STORY OF THE GRAIL