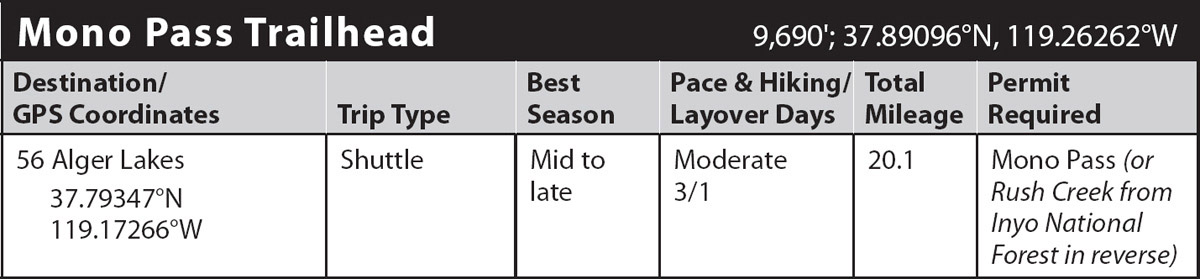

INFORMATION AND PERMITS: This trip begins in Yosemite National Park: wilderness permits and bear canisters are required; pets and firearms are prohibited. Quotas apply, with 60% of permits reservable online up to 24 weeks in advance and 40% available first-come, first-served starting at 11 a.m. the day before your trip’s start date. Fires are prohibited above 10,000 feet in Ansel Adams Wilderness. See nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm for more details. The in-reverse trailhead, Rush Creek Trailhead in Inyo National Forest, is not listed in this book as it falls within the area covered by Sierra South. Permits can be reserved up to six months in advance at recreation.gov (search for “Inyo National Forest Wilderness Permits”) or requested in person, first-come first-served, a day in advance. Permits can be picked up at one of the Inyo National Forest ranger stations, located in Lone Pine (Eastern Sierra Interagency Visitor Center), Bishop, Mammoth Lakes, and Lee Vining (the Mono Basin Scenic Area Visitor Center).

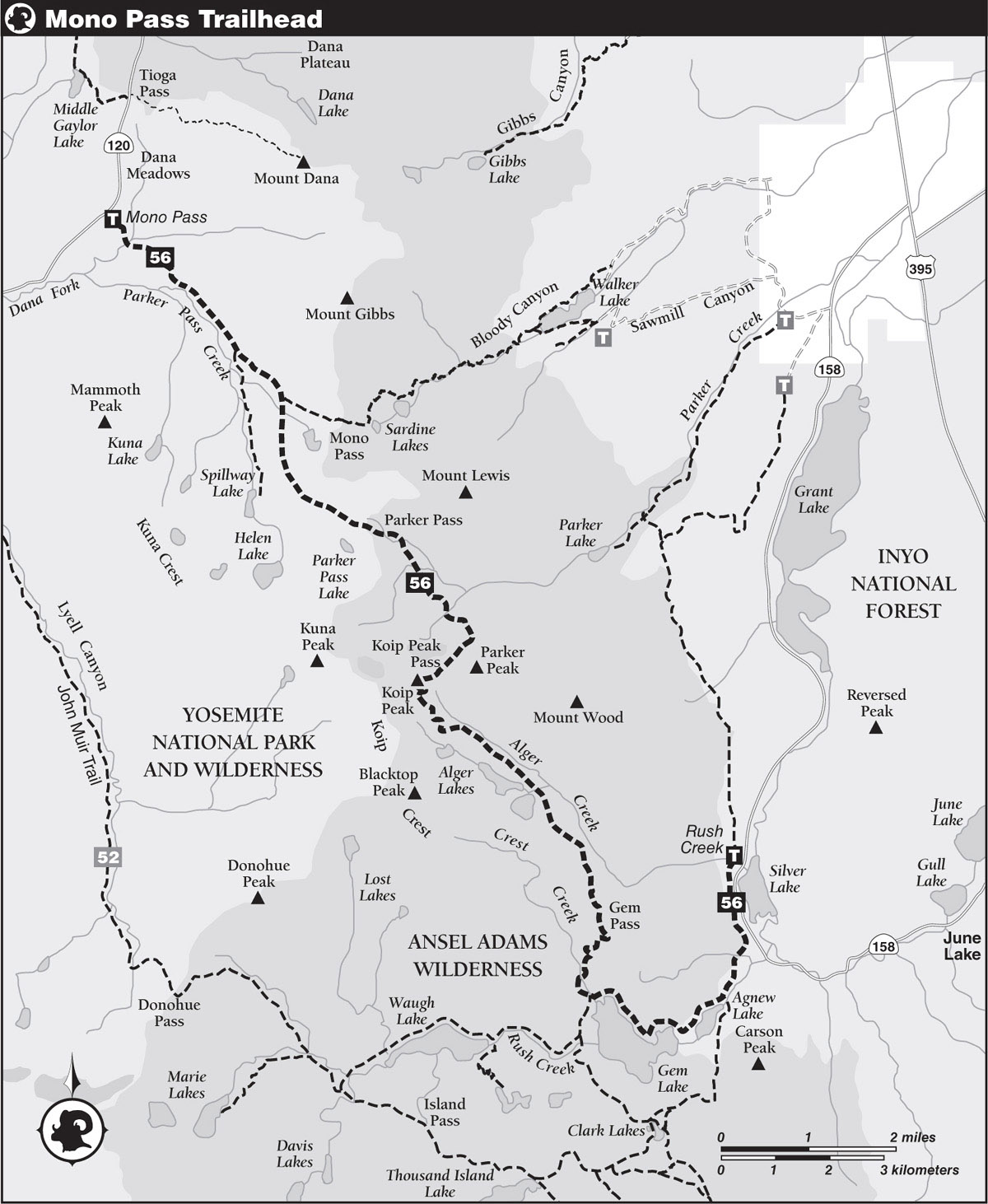

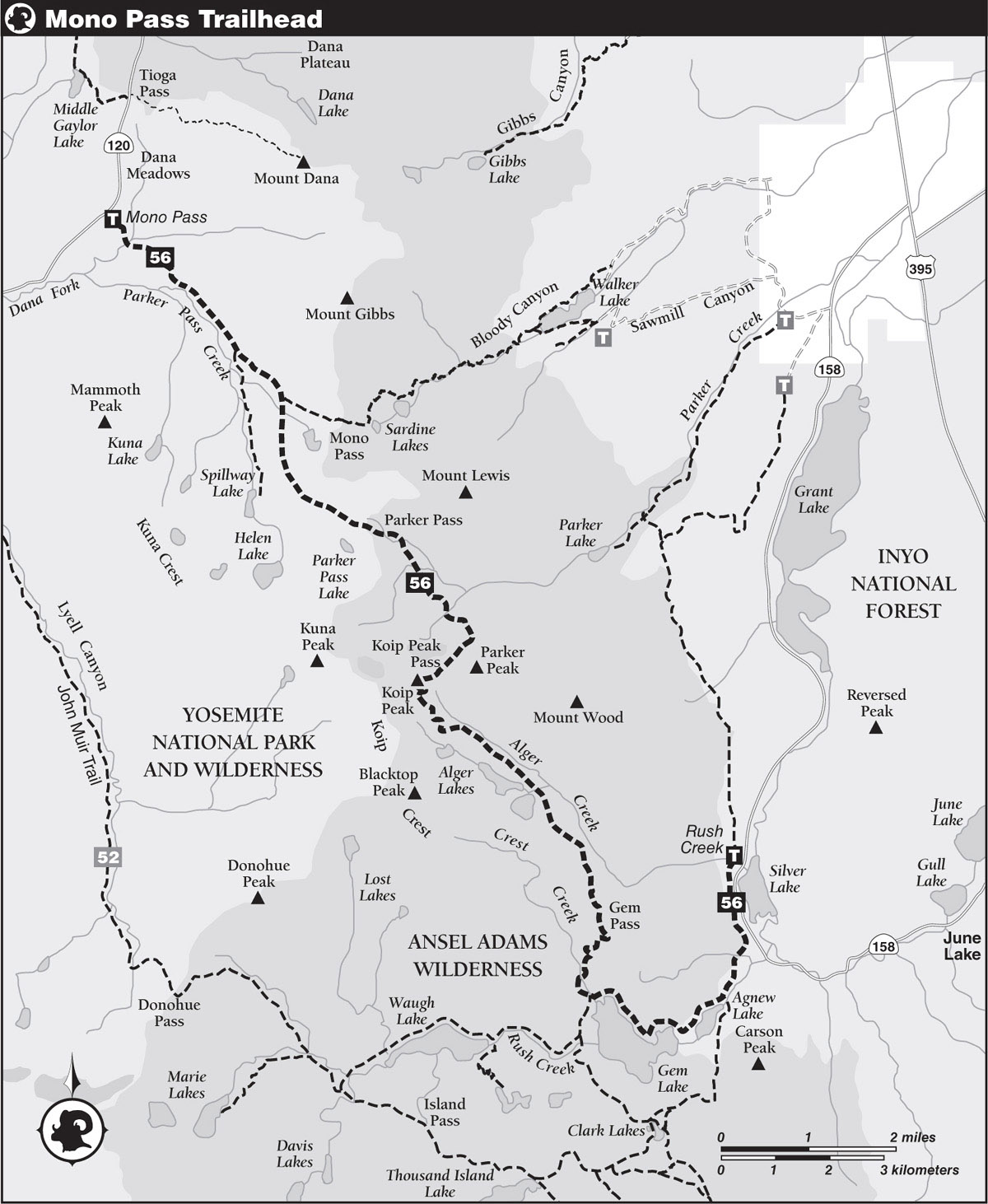

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: The trailhead is along Tioga Road (CA 120) between Tuolumne Meadows and Tioga Pass. It is located 1.5 miles west of Tioga Pass and 5.7 miles east of the Tuolumne Meadows Campground, on the south side of the road. There are pit toilets at the trailhead.

trip 56 Alger Lakes

Trip Data: |

37.79347°N, 119.17266°W; 20.1 miles; 3/1 days |

Topos: |

Tioga Pass, Mount Dana, Koip Peak |

HIGHLIGHTS: This trip offers a superb combination of views, alpine landscapes, and peaceful forests. Koip Peak Pass is the only major obstacle, and it’s easier than you think.

HEADS UP! Yosemite National Park does not permit camping in the drainage of Dana Fork Tuolumne River, which includes all the lakes and streams on the Yosemite side of Parker and Mono Passes. You must be on the Ansel Adams Wilderness side of Parker Pass before you camp.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: To reach the endpoint, the Rush Creek Trailhead near Silver Lake, head to the intersection of US 395 and CA 120 in Lee Vining. Turn right and drive 4.4 miles south on US 395. Then turn right (west) onto CA 158, the June Lake Loop. Continue 8.7 miles west and south, turning right into the Rush Creek Trailhead parking area.

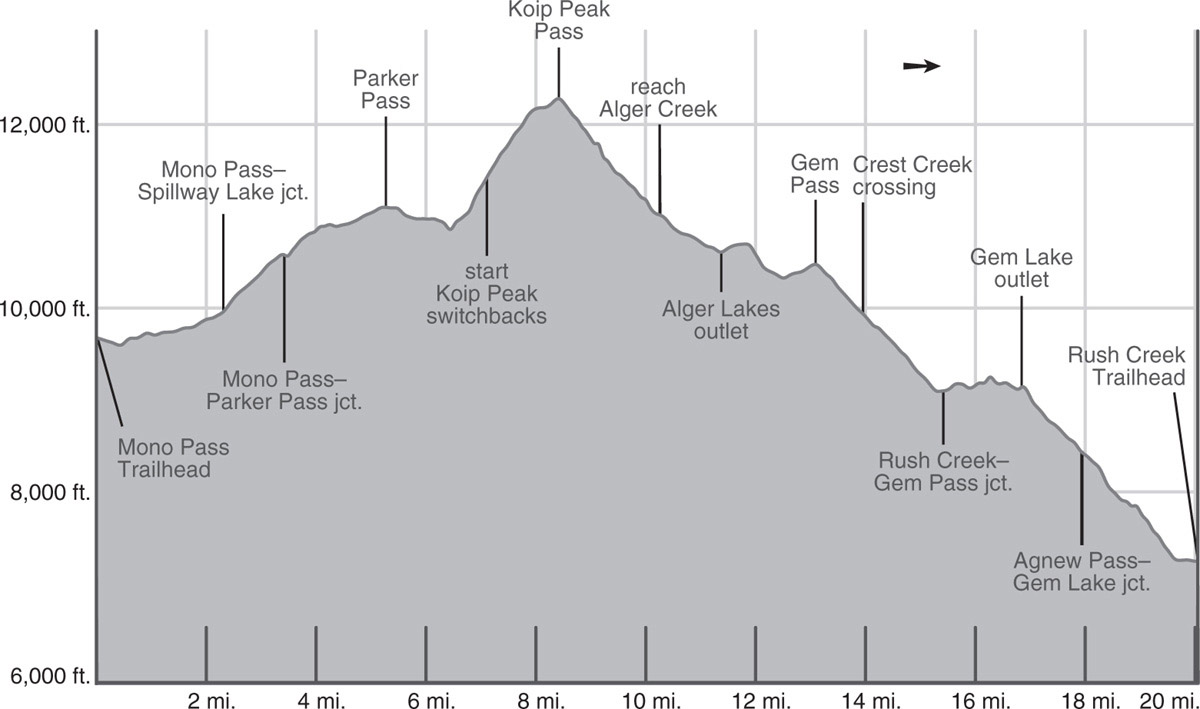

DAY 1 (Mono Pass Trailhead to Parker Creek, 6.4 miles): Starting under a dense canopy of lodgepole pines, you leave the trailhead, initially descending on a trail that once was part of a Paiute Indian route across this region of the Sierra, the Mono Trail. About a half mile from the trailhead, you cross the creeks draining Dana Meadows and the Dana Fork Tuolumne River just above their confluence. There are usually a collection of narrow logs to balance across, although sometimes these are wet-shoe fords. Beyond these two crossings, your trail climbs to the crest of a low moraine, crosses two more moraines, then, near Parker Pass Creek, comes to the ruins of a pioneer log cabin. Sagebrush intermingles with lodgepoles as you pass creekside meadows.

After 2.3 miles, you come to a junction, where you trend left (southeast), while right (south) is the Spillway Lake Trail. Take care to anticipate this junction, for the lesser-traveled trail to Spillway Lake is actually the more obvious at this junction, and if you don’t realize you’ve reached a junction you could easily ascend the wrong path. Up until this junction, your trail has been easy, but now it climbs a steeper 700 feet, up through the lodgepole pine forests covering the western flank of massive Mount Gibbs. Soon after passing the ruins of a second pioneer cabin, the forest cover transitions to multitrunked whitebark pine clusters, and before long you reach another junction, where straight ahead (left; east) leads to Mono Pass and Bloody Canyon, the continuing Paiute trail, while you turn right (south), signposted for Parker Pass. (Note: Just south of Mono Pass, 0.6 mile from this junction, are a trio of visit-worthy cabins, constructed from local whitebark pines, that once housed workers on the nearby Golden Crown and Ella Bloss gold mines.)

Dropping ever so slightly as you cross a swale, you begin a gentle climb up to the crest of a broad moraine that here and there has rusty exposures of Triassic-period metavolcanics (metamorphosed volcanic rocks), some of the oldest rocks in the Yosemite area. The scattered whitebark pines here are reduced to shrub height, and so you get largely unobstructed views that include shallow Spillway Lake, lying at the base of the Kuna Crest. Note how the granitic upper slopes of this crest differ not only in color but also in shape and texture from the lower metamorphic ones.

Onward, you see the shallow Parker Pass sitting between steep slopes more than a mile before you attain it. Yellow-blossomed bush cinquefoils yield to mats of alpine willow and, finally, to coarse gravel. The metamorphic rocks weather to small cobble-size rocks, forming a near continuous pavement in places. In due course, you reach 11,110-foot Parker Pass, where you have the most amazing broad views across the expansive uplands surrounding Parker Pass and the Mono Pass vicinity. To the north you can see Mount Conness and North Peak, while to the west is the Kuna Crest and to the east Mount Lewis, a rewarding and straightforward climb from here.

At Parker Pass, you enter Ansel Adams Wilderness. Descending on Paleozoic-era metasediments—ones even older than those to the north—you first step across an outlet creek from two nearby ponds, the headwaters of Parker Creek, then recross it at a third pond. You traipse southeast alongside a chain of interconnected, vibrantly colored tarns; different tarns are different colors reflecting the chemicals and silt composition of the trickles descending through disparate bands of metamorphic rock. Initially, the landscape appears unappealing for camping, with steep metamorphic cliff bands and endless cobble, but there are small benches to either side of the drainage that fit a tent. About 0.75 mile beyond the pass, you cross a seasonally churning tributary that gets its vigor from a permanent snowfield lodged high on the slopes between Kuna and Koip Peaks.

After another half mile, you reach an alpine tarn, from which point you can gaze straight down the enormous Parker Creek cleft. Near a tarn with beautiful rock pavings is the low point between Parker and Koip Peak Passes. Near here are some larger campsites, tucked into sandy flats, often adjacent to stunted whitebark pines (10,862'; 37.82808°N, 119.19198°W; no campfires).

DAY 2 (Parker Creek to Alger Lakes, 5.0 miles): Ahead you stare at the series of ominous-looking switchbacks that climb the northwest slope of Parker Peak toward Koip Peak Pass and appreciate how gentle Parker Pass was. Your climb begins by crossing a second snowfield-fed Parker Creek tributary, a broad cobbly crossing where the low-gradient water fans out into a braided network—take care not to slip on the algae here.

While the switchbacks ahead are relentless, the tread is well constructed and the gradient moderate, allowing you to walk upward as rapidly as the rarefied air permits. As you stop for inevitable breathers, you can scan the ever-improving panorama. You now see most of large, alkaline Mono Lake and the summits of Mount Gibbs and Mount Conness, the latter rising behind Parker Pass. During July, you may see the unmistakable sky pilot, a blue-petaled polemonium that thrives in the rockiest alpine environments, rarely growing below 11,000 feet. The basin to the southwest is a favorite site for bighorn sheep to forage—notice the green tinge of vegetation that is superimposed on the rock. The tight switchbacks lead up a northeastern-facing ridge emanating off Parker Peak and the trail then begins a final traverse west to the pass. Before early August, even in average snow years, snowfields may cover parts of the trail to the pass, and they could present a problem, since you have 600 feet of steep slopes below you. Sometimes it is safest to climb above the trail, higher up Parker Peak, to avoid the snow channels, eventually descending to Koip Peak Pass.

The gradually easing ascent southwest finally leads to shallow Koip Peak Pass, which at 12,270 feet is one of the Sierra’s highest trail passes. Indeed it is less than a 1,000-foot climb from the pass to the peaks to either side; Parker Peak to the west and Koip Peak to the east are both easily attainable summits if you have surplus energy. Leaving the pass, you exchange views of Mount Conness, Mount Gibbs, Mount Dana, and Mount Lewis to the north for ones of the Alger Lakes basin, the June Lake ski area, volcanic Mammoth Mountain, far away Lake Crowley, and the distant central Sierra Nevada crest to the south, although the Alger Lakes themselves are hidden at first.

While the steep snowfields and bluffs on the north side of Koip Peak Pass required a carefully positioned trail, the drop into the Alger Lakes basin is delightfully easy—you descend a not-too-steep easy talus slope with just the occasional switchback. The metavolcanic rock here is notably different than the older metasedimentary on the north side of the pass—paler, and forming more rounded talus. As the trail’s gradient eases, you cross Alger Creek in a thicket of arnicas, and then, with a low, fresh-looking moraine on your right, parallel the creek downstream just at the base of the moraine. To your left are expansive boggy meadows and looking east to Parker Peak and Mount Wood you’ll spy countless trickles beginning at springs high on the slope and descending to irrigate the meadow. Other springs appear at the meadows edge, where the slope suddenly breaks and the water table rises to the surface. There are campsites all along the moraine crest, in sandy patches between whitebark pines.

Slowly the trail leads away from Alger Creek to cross the multicrested moraine, the trail becoming indistinct near the summit. You are now looking down upon the two fairly large Alger Lakes. On the descent to their shore it is quite likely you’ll lose the trail at some point in the sandy, vegetated moraine soils. Simply aim for the outlet of the southern lake and shortly you’ll see a large post; the trail becomes apparent again at this point. Only 150 feet and a 2-foot drop separate the two treeline Alger Lakes. You can set up camp among the windblown whitebark pines on the bedrock landmass that separates them, or immediately across the lower Alger Lake’s outlet is a left-trending (east) spur that leads to a larger collection of campsites (10,612'; 37.79347°N, 119.17266°W; no campfires).

DAY 3 (Alger Lakes to Silver Lake, 8.7 miles): From the outlet, you climb up another moraine’s low crest, glancing back across the open terrain of this glaciated, somber-toned rock basin. Metasediments compose the northeast canyon wall and metavolcanics the southwest one. You continue following the generally open moraine crest south past a nearby lakelet (with nice campsites), then descend steeply about 300 feet to a second, then third one, these latter lakes offering only quite small camping options. The small islands in the second lakelet are large boulders that have tumbled down from the unstable slope above, a spur extending southeast from Blacktop.

Just a few minutes later, you enter your first stand of lodgepoles, then climb a very gradual 130 feet of elevation to Gem Pass. Meanwhile Alger Creek, now hundreds of feet below you, drops out of sight; you will next see it just steps from your car, where it spills into Silver Lake. It is delightful how easily the trail contours around the valley’s head, while the cleft below is impassably rugged. Note that as you begin sidling the final, quite steep slope to Gem Pass, the trail forks. The left branch descends, only to climb again 0.1 mile later. If you’re hiking in August or September you’ll be understandably confused, for the right-trending (more western) upper trail, the main route, is level and well built; however, in early July, when hard, icy snow is piled deep on the steep slope you traverse, you’ll appreciate the alternative low, less exposed route.

From 10,500-foot Gem Pass, you have your first views of the famous Ritter Range, dominated by Mount Ritter and Banner Peak. Now under a continual canopy of protective forest, you descend first through whitebark pines, then lodgepoles. In contrast to the wonderfully green, irrigated slopes you’ve been on so far, the ground here is mostly sandy, dusty, and parched. You continue down, skirting beneath a corn lily meadow, but mostly just kicking up clouds of dust on other members of your group. After you cross Crest Creek, the trail switchbacks down alongside it, slowly transitioning to a pure lodgepole pine forest, often with red mountain heather or mat manzanita as ground cover. As you descend, views of the Ritter Range are gradually replaced by filtered glimpses southeast to Carson Peak. Your 1,400-foot drop ends above Gem Lake, where you’ll meet the Rush Creek Trail near a cluster of well-used campsites. Additional campsites can be found on a peninsula extending south into the lake. Here you turn left (east) to Agnew Lake and the Rush Creek Trailhead, while right (south, then west) leads to Waugh Lake.

You must now cross Crest Creek again, a log balance or rock hop. Here, aspens—brilliant in early fall—join ranks with lodgepoles. Continuing east, the Rush Creek Trail generally stays high above Gem Lake’s steep shoreline and the terrain is inhospitable to camping. The aspens have given way to sagebrush, junipers, Jeffrey pines, and even to an occasional whitebark pine. As you stare across Gem Lake you’ll notice that a major geologic contact zone cuts across the Rush Creek drainage. This ridge and the bedrock to the north are composed mostly of Paleozoic-age metamorphic rock. These ancient rocks are roughly a hundred times older than the volcanic rocks you see above Gem Lake’s forested south slopes and at the base of Carson Peak.

Onward, the trail climbs over a ridge and passes through a corridor delineated by vertically tipped shale beds, channeling you between two rock ribs. Enjoying your view to the Sierra Crest just south of Donohue Pass, a pleasant sandy trail takes you back toward lake level, only to reverse course and force you back upward as you ease your way between bluffs near the dam’s outlet. A few spots would offer good camping, but they’re high above the lake, and the descent to water is long and steep.

Leaving Gem Lake behind and, for a spell, Ansel Adams Wilderness, you descend above Agnew Lake’s northern shore. Mountain mahogany dominates the dry, south-facing slopes, contrasting with the forested, north-facing ones across the lake below Agnew Pass. You pass some small calcitic outcrops and a nearby seep. Farther down grow giant blazing stars, whose oversize glossy yellow flowers will be blooming for late-season hikers. The flowers provide a distraction from the increasingly cobbly trail that can be tough on the feet. Finally you reach the Agnew Lake dam and a junction with the trail leading right (south) to Clark Lakes and Agnew Pass.

Beyond the dam, switchbacks carry you north down alongside a tramway, which you cross twice, before it plummets straight to the valley and you embark on a long descending traverse toward Silver Lake. At first, these slopes have mountain mahogany, juniper, and even pinyon pine, but not far beyond a small waterfall, they are gradually replaced with waist-high brush. You look longingly down to the road far below, but still have several miles to walk.

Near Silver Lake’s west corner, your trail almost touches the June Lake Loop Road, then in just over 0.3 mile, it arcs behind Silver Lake Resort and crosses several branches of Alger Creek on small bridges. It finally traverses behind Silver Lake Trailer Court to end at the Rush Creek Trailhead (7,240'; 37.78332°N, 119.12813°W).

Alger Lakes Photo by Elizabeth Wenk