Twenty-four hours had passed. We were no longer in Algeria. What first appeared to be a refugee camp, stick and palm branch shelters nestling around a pair of stone huts, was in fact Assamaka, and Assammaka was the Nigerien border post. Soldiers in khaki uniforms had seized our passports and disappeared inside one of the huts.

The twenty-four hours had been full of the unexpected. On a shelf, In Guezzam’s only shop had unlabelled bottles of a green liquid that might have been mosquito repellent. I drank five in rapid succession and burped loudly. Limeade or something. Tasted of bubble gum. Then I discovered cans of orange juice in a crate. The price, was, of course, exorbitant and quite irrelevant.

Our suite at the In Guezzam Sheraton was on the ground floor, equipped with two and a half walls, one well and one bucket, split down both sides, on a length of rope. Splendid view of the night sky. Watch out for scorpions, the driver said. I slowly filled my jerry can, promising myself never again to cross a stretch of desert with it empty. Then I put up my tent.

In the morning, the driver made it clear to us that we should seek alternative means to reach the end of the country, ten kilometres beyond town. A local pickup took us, or tried to. It also had bronchitis and conked out three-quarters of the way. We walked out of the country.

At the Algerian contrôle, Bright mentioned that he had neither Algerian nor Nigerien visas, nor the declaration form of “monies changed” expected by the officials. Would I explain, in light of the fact that he couldn’t speak French? I looked at him hoping for a wink and a chuckle. I got neither. This had better not be a border as I understood borders. In crummy French, while Bright stood mute and expressionless, I described him as “pauvre” and “misérable,” said that he had made a serious mistake (“une erreur grave”) and asked that he be allowed onward passage. Amazingly, they nodded. Victor and the girl didn’t even attempt the contrôle. Somehow they dodged it and rematerialized on the far side while Bright and I were looking about for a lift across the sixteen kilometres of neutral land separating the two countries.

Some Spanish tourists in a Mercedes picked us up. How had they managed to negotiate the soft sand between Tamanrasset and In Guezzam? They showed us: full speed, keeping to the corrugated truck-compacted piste. The swift journey was like an earthquake, my hands gripping the seat, head rat-tat-tatting on the roof. We arrived in a ball of aggravated sand, which clearly did not impress the waiting soldiers. Having been relieved of our passports, we humped our gear to the shelters.

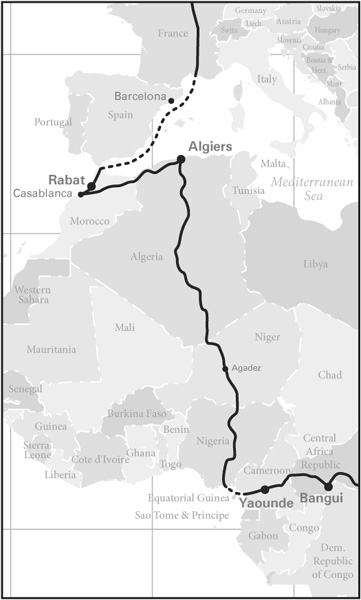

“We haftu wait for de konbye.” I assumed for most of the time I was in Assammaka that “konbye” meant convoy. A convoy with military escort would be necessary to reach the first Nigerien town, Arlit, two hundred and twenty kilometres southeast of us. The British Embassy back in Rabat had explained why in a travel advisory: “There have been armed robberies and car thefts involving foreigners in Southern Algeria near the Mali and Niger frontiers. We advise against travel in those areas.” It came with a laminated newspaper article: European jeeps had been rounded up and led away into the desert, the occupants robbed and treated to mock executions. No details. Nozzle of an empty rifle planted on the forehead? Blindfolded, sabre swished around the ears? The article had made me jittery. But the date, July 1992, made it old news — more than a year old. There were no more recent events spoken of in Assammaka, and yet a konbye was the only way to leave the desert. This sounded fishy. No doubt we’d have to pay supplementary costs for “military protection” through to Arlit.

And who exactly was responsible for these armed robberies, these mock executions? Tuaregs. The stranded community of Assammaka breathed the word. Veiled riflemen on camels, lurking behind the sand dunes, living perhaps in the fort-like towers of rock I’d seen. Lawless, cruel savages of the sand preying on trans-Saharans foolhardy enough to try crossing the desert without military escort. Mysterious, feared and revered. But were they real? I had not seen one. They could be two kilometres away, twenty kilometres away or two hundred. Was the way to Arlit a favoured highway for these highwaymen? Maybe their aggression belonged to the past.

In Le Sahara (1928), Professor Émile Gautier, “the eminent authority on the geography and history of the Sahara and its bordering steppes,” labelled the desert from Fezzan (Libya) west to the Atlantic Ocean the Tuareg Sahara. For centuries, Tuaregs had blocked Arab invasion and dominated the desert routes. They “defeated the redoubtable Arab tribe of the Uled Sliman, wiping them out almost to the last man. It was in one of their characteristic surprise attacks, taking place just before sunrise; a close hand-to-hand combat of incredible ferocity. The French column under Colonel Bonnier was annihilated in exactly the same way near Timbuktu.” Maybe there was good reason to be edgy.

The first job for us was to find onward transport. The Spaniards could take us sixteen kilometres sardined in the back of their car, but not two hundred and twenty. There weren’t many other vehicles. We spent four dead days alternating between the shelter where our belongings were and the enclosure where meals were prepared, with side-excursions well away from both to dig a hole.

My allies were now invaluable. There was nowhere safe to put luggage and no shortage of luggageless exiles mooching about. You leaned against your bags proprietorially or got a friend to watch them for you, or you took a risk and left them unguarded. I feared a midnight mugging much more than Tuareg banditry. My rucksack was the only rucksack and was twice the size of anyone else’s bag. I put my trust in Victor and Bright. I had given Victor Pepto-Bismol for his “running stomach,” which he’d had since In Salah. Evidently, Algerian well water didn’t agree with him. He’d invited me to drop by for a free haircut at his family’s hair salon in Aba, southern Nigeria. Bright lent me his razor, a Wilkinson that had to be unscrewed to be fitted with a blade. With a smear of soap, it rasped well enough over his skin, cutting the hairs, but on mine it pinched and nicked till, grazed and smarting, I had to give up. Throwing caution to the wind on the third day, I entrusted all my possessions including money belt to Bright for forty minutes and went for a jog in the desert. My entire world-circling aspirations might’ve ended right there, but that wasn’t what I thought about while I ran. Bright was someone I felt I could trust, like Mostafa. I was wondering why I didn’t have a “running stomach” like Victor’s after drinking the radiator water. Perhaps it had something to do with Assammakan haute cuisine.

Meals were a choice of goat curry, served with rice, or banku. Drinks were a choice of Fanta Lemonade, Fanta Orangeade or Coca-Cola. After the dearth of the previous days, I was quite pleased. Both dishes were filling and arrived piping hot from lidded cauldrons the size of garbage cans, stirred by a bulging woman with clammy bucket breasts and weeping armpits. Banku I particularly liked: blobby, brain-shaped dumplings swimming in goat stew. Both meals were crunchy with bone splinters and sand. I sweated cheerfully with the other diners, called for pop relentlessly, belched, farted and swatted away the squadrons of resident flies, for which Assammaka, with its oily humans, undigested goat remains and ill-hidden shit deposits, must have equalled paradise.

Slikey was the man to see about rides to Arlit. Slikey was a kind of agent or intermediary between truck drivers and vehicleless nomads like myself. Slikey. I didn’t like the sound of the name, and when Victor introduced us, I didn’t like the look of the man. Apart from the the cook, he was the only obese person I could see. He had a pencil-line moustache fastidiously following the curve of his top lip and a jawline beard of similar precision. He wore a gold-embroidered fokia with matching fez, and he squatted on a richly ornate rug with the air of a man confident in the knowledge that the undernourished and transient will satisfy his needs. Victor handled negotiations while Bright and I looked on. Slikey eyed us intermittently.

“Dis man is doobyus,” whispered the Ghanaian. I nodded. It would be CFA 3,000 each, reported Victor after a few minutes, payable in advance. CFA, Central African Francs, pronounced “see-fa.” I had none. Did Mister Slikey change money? Does a zebra have stripes? It would be 25,000 for $100, an abysmal rate but, I discovered after other inquiries, the only rate. Everyone else wanted to leave the border. Only Slikey and the Banku Queen were there to do business. When would we leave, I wondered, still confused about konbye. Tomorrow morning, assured Slikey, tucking away our money beneath his robe.

It was Saturday, the second day of our stay. Tomorrow morning, promised Slikey when we arrived at his rug at dawn on Sunday. This afternoon, guaranteed Slikey on Monday at first light. Or maybe tomorrow. Out of patience, Victor demanded his money back. The agent refused. On Tuesday, there did seem to be more of a chance of escape. Assammaka had swollen with merchants arriving from Tamanrasset, and there was much revving of engines. It was time to retrieve our passports from the soldiers.

Perhaps I was becoming marginally wiser about how to conduct myself in Africa. I let the Spaniards confront them ahead of me. After three minutes, they exited the smaller of the two huts looking as if they’d experienced their first Chinese lavatory. Each had been stung for fifty bucks. I followed on the coattails of my two allies and listened to them plead impoverished circumstances, watched them grudgingly part with CFA 10,000 each, then attempted to do the same. Travelling alone, without transport, need the money to reach my sick mother in South Africa. I parted with $25 (“Your progress will depend on your social skills”).

We were hopeful of boarding a conveyance without flapping, failing tires, a faltering engine or contraband that had to be spirited away at the destination. What our podgy agent introduced us to appeared to fit the bill. The question was, didn’t it need unloading before the thirty or so waiting passengers could be accepted? The answer to that question was no; it was in fact only half full. I was standing in front of a rounded hill of sacks, boxes, gasoline cans, plastic chairs, rugs and the accumulating baggage and personal effects of many people. Beneath the hill was a hardy looking little truck with four well-treaded wheels. It was the colour of a banana and would surely come to resemble one if called on to bear much more weight. Bright, Victor and I joined the frenzy to clamber up the stack. Once clinging somewhere near the top, I felt excited. One of several things would be sure to happen mid-journey: (1) hopelessly overburdened, we will lag behind the convoy and the evil Tuaregs, recognizing rich pickings, will nab us like hungry lions pouncing on the weakest wildebeest; (2) hopelessly overburdened, we will hit soft sand and topple over as the driver tries to take a shortcut to catch up with the convoy, then the Tuaregs; (3) the axle will break, then the above; (4) the sole white man and novice load-rider will be bounced off and left for the above.

There was considerable delay as Slikey circled the mound screaming for stowaways to dismount and settle up. Then we left, growling and wobbling, with a string of others just the same. The journey to Arlit took seven hours. Konbye, I finally learned, meant “combined”; the convoy was combined with a Nigerien Army escort for probably five or six minutes of those seven hours. A jeep with a big machine gun mounted in the back shot by an hour after our departure. After that, the convoy ceased to behave like one. Each driver veered off and took his own favourite route. The main highway to Arlit, our highway, was a severely corrugated track marked by tire remains. This rattled the eyeballs, and our chauffeur preferred to swing us around majestic rolling dunes (ah, at last), smooth as a woman’s buttocks, that we were at times punished for touching. There were no metal mats to put under the wheels of this truck, but the konbye effect of twenty shoulders did the trick. The final hour was a hurtling dash across baked flatlands towards a flickering blob of light. It was dusk, and everyone leaned forward expectantly. Arlit was lit. It had electricity; people lived there — permanently. It had bars and food other than goat. It had a sealed road connecting it with points south. The veteran load-riders broke into song. One called out a line, the others repeated it in chorus while swaying from side to side. I felt relieved and accomplished. The first big hurdle on my round-the-world circuit had (almost) been vaulted: the roadless heart of the Sahara Desert. Even Bright seemed bright. He was humming.