Alone again. Scrunched between women slung with babies and scrawny men with distraught chickens tied at the ankles dangling upside down between their legs, I rode buses and minibuses south through Niger and Nigeria. Some were rattly old crates with busted-up seats and fumes guffing up through the floorboards, others had spray-painted flames flaring down the sides and frilly curtains with tassels dressing their windshields. My knees butted the seat back ahead of me, and I was gaped at with unceasing interest, but I enjoyed these unpredictable rides, with all the unexplained midnight bus switches, arbitrary any-hour meal stops, breakdowns, military roadblocks and everyone-out shakedowns. I might join a scrum and fight for a seat, or I might be the first aboard and sit for three hours alone or with one or two others. At twenty-minute intervals, buses liked to cross bus stations at walking speed, driver bellowing out his destination, boy hanging off the side-view mirror trolling for passengers. On the road, we stopped often, picked people up, set them down, pulled in for snacks. Children climbed on at each stop to sell shreds of goat on wooden skewers, oranges with their skins shaved off or Coca-Cola in plastic bags.

On the bus from Kano in northern Nigeria to Aba in the south, as we drove heedlessly and headlightlessly through the night over what felt like bomb craters, Bob Marley lulled us: “Everythang’s gonna be awlrye.” My eyelids drooped. Then, WHACK! Ejected from my seat, head smacking the roof, van shuddering as though booted by a giant. By dawn, I was dizzy and wobbled on my feet as I got off. I felt as if I’d just crossed an asteroid belt in a garbage can.

During the waits I daydreamed of the jungle. Rich, matted swathes of it, spilling over sluggish brown river water, yellow-bellied crocodiles sliding in off sand spits, snouts and ears of hippopotami breaking the surface, long-tailed monkeys leaping between branches and screeching overhead. I had my mind set on boarding one of the “floating villages” that my guidebook talked of. I would nudge along some arterial river for a week or two, stepping over trussed-up crocodiles with their mouths wired shut, dining from pots of monkey stew perhaps, watching men hanging over the back fishing. Acres of time to lean on a rail and admire giraffes tearing at tall leaves, elephants jogging along the bank. Kids would pump pirogues laden with bananas and pineapples up to our floating village.

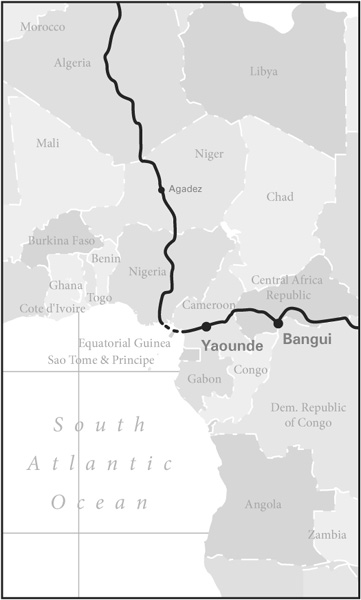

The air had thickened. Desert yellow had hydrated into jungle green. I would cut across the continent now, Atlantic Ocean to Indian, from Cameroon through the Central African Republic, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and Uganda to Kenya. See all the remarkable wildlife fed to me by Tarzan films in my childhood, honk idiotically at the hippos like Bogart in The African Queen. The sand from the Sahara was out of my sacks and socks, and I was clean and tidy after my stay at Aba and my haircut at Victor’s salon. My “running stomach,” which had begun in Arlit, thanks to my drink of truck radiator water, was quiet. On the morning of my departure, Victor’s sister had boiled a delicious mash of haricot beans and plantain for breakfast and served it to me, splashed with Carnation milk, in a metal bowl.

I arrived at the Nigerian port of Oron late in the afternoon of November 17 and looked about for something my guidebook referred to as a “flying boat.” The book said that a flying boat could take me across the Calabar River estuary and then a stretch of the Gulf of Guinea to Cameroon. I thought this might be a relaxing change from land transport. I would catch a glimpse of the ocean. But what exactly might a flying boat be? Certainly not a seaplane, I knew that much. It sounded brisk and efficient — a rapid alternative to the land route taken by European overland expeditions in their trucks and Land Rovers, which went from Enugu to Douala, crossing the border at Ajasso.

Oron was an unmarked tumbledown immigration hut glued to a tarry riverbank, a cluster of boatmen herding jittery passengers with inflated truck inner tubes round their waists towards splintery fibre-glass launches. These were clearly flying boats. Slim hulls, pointy bows, outboards. Earlier in the day, a plodding ferry had carried me from the port town of Calabar to this riverbank. The ferry was the only other type of vessel around. Brisk or not, the launches would certainly fly by comparison. I would allow myself to be shepherded. But first a visit to immigration for an exit stamp.

I got the stamp and a ticket for the boat, but when I tried to leave, a bony man with black teeth and predatory eyes blocked me. He put a bent and curly-cornered card under my nose for inspection: “Narcotics Agent.” There was a photo of the agent’s face, a number and a squiggle at the bottom. I ran my eyes over him. Unless Africa was earthquaking my assumptions again, this was no agent. He looked like a convict, or at best a flying boat boatman: shoeless, mud-caked trousers rolled to the knee, the perforated remains of a shirt hanging from his chest, shaggy-chinned. The card and the bearer surely couldn’t be a match. Definitely doobyus.

I looked around to see if anyone was laughing. Cameroonians were mooching about uneasily. The agent demanded to see my passport. Next my bags. He demanded a document of permission to travel through Nigeria. I had no such thing. Still no one was laughing. Immigration officers behind their desks, tidy in light green short-sleeved shirts, one with epaulettes, thumped the remainder of the passports.

“So what shall I do?” the agent said finally. He seemed to be addressing the room, sitting now on the corner of the ticket table, arms folded, smug. Sensing a definitive moment, the milling crowd stilled.

“How about . . . some cigarettes?” I ventured. I had picked some up in Rabat to oil border crossings.

“Ha, he thinks because I have black teeth. What am I to do?”

Silence.

“Achète-lui une bière,” suggested a sympathizing Cameroonian nearby. The scruff scoffed some more.

“I can stop you,” he said, with considerable menace for a man lacking any outward vestiges of authority. Could he? On the grounds of being without the spurious travel permit? I turned to the wall and rummaged in my neck pouch under my T-shirt for some hard currency. A $20 bill surfaced. No. A ten. I scrunched it up, passed it to him. Wide grin. Should’ve given him a five. He strutted out, challenging no one else. A dollar bill even. A victorious rooster. Still no one was laughing. I felt foolish.

“WHITE MAAAAN!” A three-and-a-half-hour wait in a motionless flying boat followed while the boatman searched for the fourteen passengers he needed to fill the eight-seat launch and seriously compromise the waterline. Afternoon turned to evening. Mosquitoes appeared and began to feed. I sat in the stern and slapped. The quaysiders bathed starkers and shouted gleefully at me while chucking water over one another. I watched turds and banana skins nodding in the waves they made. Darkness. The man who had sold me my ticket came. I was putting DEET insect repellent on my neck and ears.

“We go tomorra mornin,” he said. “Ut six.” Ah, good, a plan. At six. Something to latch onto. I liked this man even though I knew he had made the number up. New passengers would not materialize in the dark. “What kills you here is the uncertainty. You just never know. Neither does anyone else,” travel writer Eddy Harris wrote on his journey through central Africa a year or two before me; he had been waiting a week for a steamer to take him up the Congo. The flying boatman squatted and considered me. He’d seemed pretty gruff earlier, yelling at some of the more quarrelsome passengers. He was brawny and stern, a little older perhaps than the other boatmen. “You not safe here.”

His motorbike charged up a steep dirt track behind immigration while I clung to his hips, trying not to be chucked off, the weight of my backpack throwing me to left and right. After fifteen minutes, we were at a small guesthouse. Only the lobby was lit. The ticket man dropped me, sped off back down the track. I had a meat pie and a warm beer in the lobby, then watched an Avengers episode on an old black-and-white TV with a jumpy picture.

The motorbike returned at five-thirty in the morning. I was back in the boat at six. The only one. An hour passed as other passengers reassembled. Another two were spent on boat trials. These involved gunning out from the quay at full throttle and listening carefully to the engine while drawing a huge circle in front of the immigration hut. This was done in the boat I had joined the day before. Then I was shifted to another. Then a third. Then back to the first after the “mechanic” had “fixed the wire.” I don’t know quite why I followed the instructions, moved, sat and circled each time. I could have stayed on the quay. I knew that we wouldn’t leave for Cameroon till we had a full boat. And yet . . . I was not alone with the flying boatman during these trials. One or two Cameroonians joined me. Like me, they probably believed there was an outside chance of the early bird catching the worm, of one boat making a dash under-loaded. Tempers flared as it became clear that bus rules in fact applied: full is when the vehicle is brimming with bodies. At ten-thirty, one dizzy passenger tried to hit the flying boatman after being invited to get back in the original boat. There was shouting, cuffing, grumpiness. People calmed down. Got testy again when a fair-sized group had gathered but the boatman insisted on waiting for two more. The ticket man reappeared and asked me what I had for him. I winced. He had saved me from a night in the hull of a flying boat and I had given him nothing. Why didn’t I have a pocketful of handy items like sewing kits or lighters to give to people who were kind? I reluctantly parted with one of my three T-shirts.

Finally, with the full complement of passengers aboard, it was seen that the flying boat . . . wouldn’t: it was taking on water and in danger of sinking. I should perhaps have been one of the two who nobly volunteered to disembark.

Instead, I clutched my spattered rucksack and refused to budge, the only one not plump and cozy in an inner tube. Out we went again. Then I realized we were not doing another circle. We were heading boldly for open sea. We flew (in an average motorboat kind of way) for maybe ten minutes. Then abruptly stopped. Puzzled, I looked this way and that for a cause. Two launch-loads of armed men overtook us, one on either side, in a deft pincer movement. Shit. Pirates, their rifles trained on our heads. I shrunk down in my seat, looked again furtively. But hang on, these men were wearing khaki uniforms, berets. I exhaled. Nigerian Coast Guard. They called for passports, barked questions, demanded fees for their protection. This smelled familiar. Konbye, Nigerian maritime style, was it? Ten minutes after they let us go, the same happened again. One boat this time, two grinning soldiers. Passports out, questions, fees. But I was in a good mood, pumping along at a reasonable clip tracking the lush coastline, a little water sloshing in from time to time. Pretty soon, I’d enter my fourth African country. Cameroon. I looked ahead for some sign of it in the mist.

Little waves began smacking the hull. Instead of cleaving the water in a nice V, the flying boat was now bumping along, rising and dipping. The waves got larger. The bow climbed them and slapped down in the troughs, causing snots of spray to fly up, streaking our faces, our bags. I could hear moaning from the seat behind me. Then the bow suddenly reared spectacularly. I grabbed the side with one hand, my two bags with the other, regretted being one of the two up front. Down, slamming the surface. Water rushed in. Up again. My plank seat, not fixed to the boat after all, jumped out of its slot and repositioned itself in the laps of the row of three behind. There were yelps, some squeals.

“Scusez-moi, I can’t, um . . .” I fought for balance, tried to keep hold of my day pack as well as the wandering seat. The bow reared again, nose-dived. It was raining hard. I reslotted the plank. We took off again, thwacked down. Screams, black arms waving either side of my head. I had let go of the plank entirely; it was now behind my ears. I rested between a pair of knees, a rubbery inner tube behind my neck. I understood the importance of these now . . . and the plastic garbage bags all the other passengers were wearing . . . and the repeated test runs in front of Oron. This was going to be a fairground ride.

The Nigerian flying boat (well-named), launched itself off wave crests and buried itself in the troughs beyond. Baggage flew, passengers bounced and bawled, water washed in around our ankles, the skipper bailed with half a cracked plastic bottle. I noticed with each leap that the wind was not hitting us quite head on. We were twisting in the air. With the correct angle off a wave and enough of a gust, we would flip. Drenched and shivering, I considered this in a panicky, helpless way. I saw myself dumped in the drink, arms flailing uselessly in the choppy water, all belongings gone, passport in soggy tatters, journey around the world finished. I tried to lean over to compensate. I should somehow try to attach my bags to the boat. Should have. Everything was in turmoil now. I could only crouch, cling and pray.

Then suddenly the wind and rain came at us from the side. We were heading for shore. I wiped my eyes. No huts. No sign of Limbe, our destination. Instead, a river mouth. Shelter. Soon a dense wedge of forest stood between us and the storm. The skipper revved down. Rain pitted flat water. We hung our heads. “All this is normal,” said a weak, unconvincing voice in my head that I’d heard before. “Nothing to be overly concerned about here. This is how Africans travel.”

I wrung out my T-shirt, tipped the water out of my boots, yelled at the skipper to put me ashore. It’d been a nice day in Oron. We went round some bends and seemed to be paralleling the coast. Then a gap in the trees appeared. The boat picked up speed and curved towards it. Everyone huddled down, braced for impact. The rain slanted into us, waves pummelled the boat. Flying boat flew. My plank seat chinned the Cameroonians behind.

Then we stopped. The yammering engine cut off mid-sentence. I wiped my eyes, looked round, froze. Another boat was drawing alongside, three of its four occupants pointing guns at us. No uniforms. I sighed. Well, if we’re gonna flip and drown, someone may as well have our luggage beforehand. The two hulls clunked. One of the men set his gun down and reached under his seat. A length of rubber hose. Straddling the two boats, he began thrashing the flying boatman with it. He screamed abuse in his ear with each stroke. We looked on silently.

“Qu’est-ce qui se passe?” I whispered to the man sitting beside me.

“Our boatman he doesn’t stop when police call him.” Ah, so these must be Cameroonian coast guards. I wondered if they carried the hose specifically for the purpose for which it had just been used. Passports, questions. I told them I was British and was visiting the country for the first time. I wasn’t thrashed. There was, of course, “un petit cadeau” required for coast guard services.

Three hits for cash at one border crossing — four including the narcotics agent. That was a record. Why the heavy policing? Was smuggling such a problem around here? Maybe the border conflict was partly to blame. Somewhere to our left was the Bakassi Peninsula, an area of mangrove islands marking the meeting point of the warm east-flowing Guinea Current and the cold north-flowing Benguela Current, a fertile fishing ground: also, supposedly, rich in oil. Nigeria administered the territory in accordance with treaties made between colonial powers and local rulers dating back to 1885. Cameroon claimed possession through agreements settling maritime boundaries between the two countries signed in the 1970s. A couple of months after I left, thirty-four soldiers — thirty-three Nigerian, one Cameroonian — would die fighting here. In March 1994, Cameroon would take the matter to the International Court of Justice.

The engine was re-fired and we bounced onward, me clinging and swearing at the sea, the storm, the plank seat and my idiocy for choosing to enter Cameroon by boat. But then the clouds broke, the rain stopped as quickly as it had begun, and the sun shone through. It illuminated a nest of bamboo huts — Idenau, a small village on the way to Limbe. Fine. Terra firma. We nudged in, tossed our bags on the sand, tottered ashore queasily.

“The only time I’ve ever been afraid at sea.” I had glossed over this line in my guidebook, a comment by a merchant seaman describing his boat trip from Oron to Limbe at the end of the section called “Getting to/from Cameroon by Sea.”

“Passeport?” My hand was shaking. The immigration officer eyed me suspiciously. He inspected my visa. “Et pourquoi avez vous decidé d’entrer au Cameroon par bateau?”

I do not remember much about Yaoundé, the capital. I wasn’t there long. I recall a surprisingly modern downtown: wide boulevards, a flashy telecom centre, a government building, inventively designed with a zigzag motif on the front like an open mouth, overlooking Place Ahmadou Ahidjo. After my two-kilometre morning walk from the Foyer International, where I was staying, to the telecom centre, I was glad of barrows selling juicy wedges of pineapple and papaya. Yaoundé was hilly, the air sticky. Yellow Citroën and Renault taxis buzzed up and down the main streets. The hills surrounding the town were luxuriantly fuzzed in foliage, some with wood houses roofed in corrugated metal creeping up their slopes. Deeply grooved, rain-washed red dirt roads separated the hills.

I got a visa for the Central African Republic, called my parents, said anything could happen from here and wished them a very early Merry Christmas. I would take the train north to N’Gaoundal, then something else west to Garoua-Boulai and the border. At the railway station, I bought a ticket, boarded the train and met a gang of youngsters sprawled over the seats demanding “seat reservation fees.” Not in the mood for more fees, I took a firm grip on the nearest pair of ankles, yanked and swung the owner of them into the aisle. Hullabaloo. Like poking a stick into a hornets’ nest. A rain of insults echoed round the carriage, but I was bigger than the biggest of them. Fortunately, the train began to creak out, meaning they had to jump off or come with me to N’Gaoundal.

I chained my rucksack to an overhead rack, tucked my day pack under my seat — putting my leg through one of the shoulder straps — and settled down for the night. Now I felt I was really heading into the heart of darkness. Not a gloomy prospect, but definitely a nerve-wracking one alone. I had a seat on a train, the train was moving, and I knew that sometime during the night I would arrive at the destination on the ticket. Past that, there was no telling what would happen. My mind fixed on a mythical river and the rush of wildlife I imagined on its banks.

At N’Gaoundal, I was jolted to life by a rowdy exodus off the train into waiting bread vans. It was five o’clock. A bread van is a hardy four-wheeled truck used as a bus in central Africa. It can grind out long kilometres over rough terrain, go up and down greasy slopes and up and over boulders and fallen branches, and merrily churn its way out of shallow mud-filled potholes, of which there is no shortage in Cameroon after the rainy season. Luggage is tied to railings on the roof and a sheet of canvas is drawn overtop to shield it from rain and raking branches. Passengers perch on metal benches of a width better suited to bread buns than buttocks in a metal cabin with glassless slit windows behind the cab. For eight hours, I lurched from side to side in a bread van, gripping the seat ahead of me and trying not to slide into the two passengers to my right or the three to my left. Flies sailed into the cabin and buzzed around our heads, settling here and there to drink sweat.

We arrived at Garoua-Boulai in mid-afternoon, a mass of bodies spilling out of each van onto a square of packed dirt. My legs were numb, my knees banged and grazed. I looked about me dopily, saw a bamboo hut with tables and chairs. A boy chucked my pack down from the roof rack. I staggered with it like a drunk to the café, collapsed into a chair and bought a Fanta. The girl working there grinned at me. No doubt she saw such specimens all the time. She was twenty-three or twenty-four, with small eyes set wide apart, red plastic earrings, crinkly hair tied back.

“Quel pays?” “Vous allez à Bangui?” “Vous voyagez seul?” What’s my job? What’s my name? I looked around, wondering where all the other passengers had gone. And how old was I? I slouched, not wishing to be interrogated but reluctant to leave. I tried to keep my eyes off the girl’s braless breasts, which were hardly contained by the shirt she was wearing. Thought back to my girlfriend in Japan. Akemi had not needed a bra, would never need one. Yet she wore one even in her own apartment as if it was a cardinal sin not to.

There was a coughing, spluttery engine sound and a motorbike drifted to a halt next to the newly abandoned bread vans. A westerner climbed off the back. He was skinny, had a short beard, carried a tatty rucksack and wore jeans split at the knees and unravelling at the ankles over mud-plastered toes and flip-flops. Crusts of mud stuck to his trouser legs. A quarrel began, the man throwing his arms in the air, shouting, poking his short, stony-faced chauffeur in the chest, finally slapping some crumpled francs on the bike-seat.

“Merde. MERDE! Toujours la même merde . . .”

Olivier Chotard was French, twenty-three and on his way to Madagascar from Guinea. He joined me in the café, shook a bent cigarette out of a flattened packet from his breast pocket, waved at the girl to bring him a drink. We chatted for an hour in English, agreed that getting around Africa was no picnic. Like me, he was taking whatever local means came to hand. Evening came. The largest building in Garoua-Boulai was the Catholic mission. My guidebook spoke of missions putting travellers up for a night or two for a donation. We rapped on the door. A Polish priest with a grey and white beard corrugating down to his stomach welcomed us. Over a dinner of chicken and rice, we quizzed him on the Central African Republic, but he could tell us little beyond the fact that few Europeans were stopping by on their way there. Olivier’s mission, as I would discover over the next few weeks in C.A.R. and beyond, was two-fold: get things at the right price, and find a woman to sleep with in every village. He wasn’t carrying a tent.

After dinner, we went to Garoua-Boulai’s only bar. We drank Zairean Primus beer and made plans. As we were heading in the same direction, we would stick together for a while. Olivier liked the idea of a boat journey on the Congo. He wanted to see gorillas in Rwanda. Both of us looked forward to safaris in Kenya or Tanzania. Then there was Zanzibar. Victoria Falls. The girl from the café came and sat with us. She laid her hand on the inside of my thigh and nodded as though she was coming on the journey with us. Olivier laughed and winked at me. She trailed us back to the mission. At the door, I said au revoir, but my new French companion had other ideas. Arm round her waist, he steered her towards his room.

“I tell ’er you ’ave malaria. You can’t do une érection. You don’t mind if I ’ave a little fun, eh, Tony?” I wondered if the priest had turned in for the night.