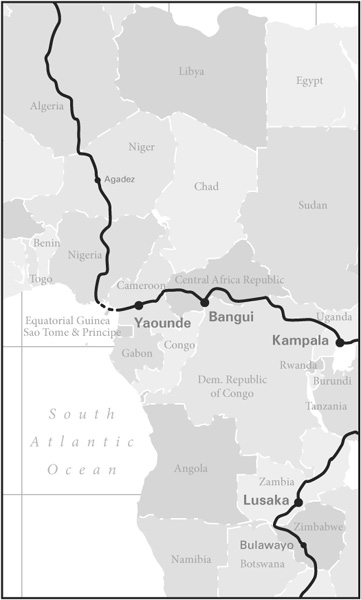

“The Central African Republic is an undeveloped, fragmented and poverty-stricken country.” I read the words in my guidebook and the historical summary that followed, but little sank in. Rich in uranium, copper, iron, tin, chromium and diamonds, capable of exporting timber, cotton, coffee and textiles, the C.A.R. could be a prosperous African country if it weren’t for a succession of dictatorial and repressive regimes. As it is, it is one of the least developed, one of the most reliant on foreign aid. When I crossed the border, General André Kolingba was in power. In 1986, he had made his party the sole legal one and banned all opposition groups and any political activity. Seven months before my visit, students, schoolchildren, and civil servants who had gone unpaid for months demonstrated on the streets of the capital. In the subsequent riots, police killed two and injured forty-five. The C.A.R. had nearly 24,000 kilometres of roads, of which only 440 kilometres were asphalted. It would be a bread van to Bouar, another to Bangui.

In Bouar, the guidebook recommended that we stay at Chez Pauline. Pauline was described as “a big mama,” and we would find her sitting on a stool outside her auberge near the bus station. The edition was over a year old. Would she still be sitting there? Beaming, waving us over, Pauline was the portliest woman I’d seen in Africa, bigger than the Banku Queen of Assammaka. I couldn’t see much of the stool. Chez Pauline was three lightless, doorless, mud-floored rooms with single beds, the mattress on each draped with a yellowy-brown, dead-bug-smeared bedsheet. I felt that I could leave my bags safely in one of these rooms. No one would get past Pauline.

On our one and only evening in Bouar, a drunk stopped me in an alleyway and shoved me against a wall. I could make out a beefy man in shorts with a beer bottle.

“Dollar! DOLLAR!”

“Non.”

“BÂTARD!”

Oli and I had been out searching for a bite to eat. Bouar had no electricity and was short of food. We groped around in the dark, could find only cold goat brochettes and cassava bread. Perhaps they’d stopped serving food when the sun went down. On our way back to Pauline’s we got separated. One moment Olivier was a shadow in front of me, the next he was one of several going in different directions. I shoved back, which angered the drunk. Bellowing abuse, he chased me in circles around Chez This and Chez That till I chanced upon an open doorway. A bare foot thumped my arse as I ducked inside. A bar. Packed solid. Bouar was not short of beer. I wriggled through a knot of bodies illuminated by a stuttering lantern and exited next to a heap of empty bottles.

Sleep that night was fitful and brief. The lack of a door troubled me. At four-thirty, a stranger shook me awake (I believe I yelled) and put me in the bread van for the capital. The vehicle joggled and slid over a dirt road in the dark; we moaned and jerked in and out of semi-doze.

“So, Olivier, did you sleep with Pauline?”

“Ah, Tony, you are, qu’est-ce que c’est? Jalooose, no?”

I slept through much of the journey but was definitely awake when, at the city limits, the van was commandeered by soldiers. One crouched inside, covering us with his revolver; another clung to the outside and shouted at traffic. A jeep with more soldiers in it followed us. The driver was told not to go to the bus station. Instead we were taken to see the Secretary of the Interior.

“Et combien de jours êtes-vous restés à Bouar?” The Secretary was about fifty, with a wide, precisely scissored moustache and shaved head, splendid in his spotless pale green uniform with pips on the shoulder and creases in the trousers. And how many days did you spend in Bouar? This and other questions to each of us in turn. He listened to our answers, head cocked, eyes narrowing doobyusly.

“Un soir” or “deux jours,” we replied in cowed voices. Eleven of us stood in a large airy room with soldiers stationed in front of the doors and windows.

“VOUS ÊTES AGITÉ?” This screamed at a sleepy Cameroonian scratching his chin. I looked at Olivier. What on earth was this all about? Would we be frog marched off to jail for spending un soir in Bouar? The Secretary marched out of the room, came back a moment later, seized documents lying on his desk and threw them down with an irascible click of the tongue. He sat down, bolt upright in his swivel chair, and considered us.

A sergeant entered, bent and whispered something in the Secretary’s ear. The Secretary’s face suddenly uncreased and broke out in a smile. He waved the soldiers away, leaned back in his chair, said “Bienvenue à Bangui” to us in a cheery, no-hard-feelings tone of voice. Welcome to Bangui. It was like the sun parting the storm clouds on the flying boat to Idenau. We shuffled outside, dazed. In the bus, someone muttered something about the authorities being after drug-runners, some of whom were foreigners. Olivier shook his head.

“I was, how do you say in English, très inquiet?”

“Shit-scared? Me too.”

After this experience, we were not especially inclined to go sightseeing. Besides, I was feeling a bit funny — as if I wasn’t firing on all cylinders. A grogginess that I couldn’t shake off or blink away lay over me. I put it down to short nights, skimpy meals, stress and the sticky air.

We hid in a place called the Centre d’Accueil Touristique (Tourist Welcome Centre) outside town. It had a tall fence around it with barbed wire on top and was owned by an elderly Dutch woman called Gertrude. We could get omelette, baguette and coffee from a table by the gate. With Carnation milk stirred in, the coffee was delicious: strong, sweet and addictive. The Welcome Centre had cabins with mosquito mesh curling off the windows and heavy muslin nets suspended from the roof over the beds inside. Undisturbed slumber. Luxury. Except that I slept with one knee resting against the net on our second night and woke in the morning pinpricked and itchy. Olivier sweet-talked a girl into running errands for us in town. She came back with cigarettes and barbecued goat wrapped in newspaper. In the evening, I tried jogging the perimeter of the centre to rid myself of my thick head. Just as the mosquitoes were beginning to bite, Oli went off hand-in-hand for a shower with the girl.

We ventured into town once to get visas for Zaire: large, inexpert, blue splodges in our passports costing an outrageous eighty dollars, the most expensive yet. Bangui is built on the north bank of the Oubangui River. On the south bank is Zaire. We could cross right here and enter the new country at Zongo, but the word was that officials on both sides would milk us for all they could with fees, tariffs, fines and “un petit cadeau, monsieur?” We could also cross at other points upriver, the nearest being Mobaye. Overland expeditions from Europe liked to cross further east at Bangassou.

After two body-wrecking bread van journeys from hell, being shaken silly over the worst roads yet, having had nothing decent to eat, and not drinking nearly enough water in the muggy jungle heat, we arrived in Mobaye to find the border closed. A man who lent me a chair to collapse into filled us in on a few facts. I was zapped, giddy, had a jet of diarrhea pressing to be released, could only half listen. Ubangi du Nord, Zairien President Mobutu’s home district, was across the river from Mobaye. Non-Ubangi needed permits to visit. Gbadolite, the president’s town there, was rumoured to have the best-stocked arsenal in the country. Mobutu was building a palace there. The place would be crawling with soldiers. And soldiers in this part of the world — underpaid, sometimes unpaid, always after money and at times out of control — are best avoided. Zairien soldiers had gone on violent rampages, rioting and looting across the country in 1991 and again a few months ago, when sixty-five people died, including the French ambassador. Keeping the lowest possible profile and staying as much as possible off the beaten track was the way to go. Certainly not into Mobutu heartland.

Can’t see clearly. Can’t think. Got the shivers. Stutters too! Mud hut, bed, blackout.

Awake. Where am I? Head pounding. Bright light, a voice. A bearded man in the doorway with a chicken held upside-down by the legs, feathers flying off. I try to laugh but my teeth chatter. Hot, now cold, hot again. The man shakes the chicken. It squawks furiously, beats its wings. He laughs, leaves. Wood door bangs shut. Black walls. I huddle like a frightened child. Would like to turn a bucket of water over my head, the bucket in the corner, the corner where there is a hole the size of my fist in the wall, shock some sense into myself. But I see a three-inch red centipede winding in and out, can hear its skittering legs.

A woman came from the mission earlier. Gave me pills. Must swallow four every three hours. Must drink from my jerry can. Purified river water. Yellow, reeking of iodine, globs of dead stuff floating in it. Close my eyes and quaff.

Sitting outside on a wooden chair, I see a brown river to my right. Smouldering fire in front. Teenage girl wearing charcoal-scuffed tablecloth pokes it.

Goose pimples. Fingertips numb. Head thumping. Shivers. Hot, cold, hot. Totter inside, remember the advice. Drink. Want to vomit. Drink again. Fall back. Sweat. Stupor. Dream of England, my parents’ cottage, safe and sound, curtains closed against winter.

It lasted two days and two nights. Olivier shook me at three-hour intervals during the nights and made me take chloroquine tablets, the assumption being I had malaria. He’d had it a few times himself in Guinea. Malaria? Surely not. I had been taking my Paludrine and Maloprim, the recommended prophylactics, dutifully since Sapcote. But I had all the symptoms: severe headache, the shivers, fever, aching muscles. I had diarrhea, too. I’d had that almost non-stop since Rabat. Not discerning enough about what I ate . . . believing wrongly that I had a stomach lining of cast iron after years of eating raw fish and fermenting beans in Japan. Collapsing was new. Perhaps I had dysentery or giardia or hepatitis — Oli should check me daily to see if I was turning yellow. I looked out for blood in my stool but found none, though the inspection was not easy in the back of a lightless hovel.

Olivier brought me chicken and rice for lunch on the second day. I toyed with the food, utterly drained, as if I’d spent fifteen rounds in the ring with Muhammad Ali. It was almost too much to sit up and lift rice to my mouth. I had a tendency to keel over and drift off into waking nightmares of soldiers prodding me with guns, asking politely for petits cadeaux.

What if I’d been out here alone? Stopped dead in my tracks like this. Middle of the jungle, no idea how or where to get help, unable to make myself understood. And I thought I was tough enough to survive anything Africa could throw at me with the bare minimum of help — odd pointers in the right direction, that sort of thing. Think again. There was a lesson to be learned here. I was probably moving far too fast. I had not appreciated that each journey exacts a toll on the stranger unused to the knocks and bangs, the delays and uncertainty. I had not tuned myself to the pace of life and travel in Africa. Had to ease up, be less impatient to forge ahead, enjoy the ride, stop stampeding through like a hunted zebra. And I really should start eating at least one proper meal a day and drinking every hour, regardless of what the water looked like.

Thank God for Olivier! I was as desperately grateful for him as I had been for Bright, my trans-Saharan companion. It was scary enough being weak and helpless with just a young Frenchman around. Strange, I thought, how in difficult circumstances you build a quick trust in someone you don’t know but sense is decent. We’d been together a matter of days and here he was nursing me back to health like a mother. Not that the interruption in our journey seemed to bother him. He slept on a rug with the girl I’d seen tending the fire. I looked beyond to the river. It seemed very muddy and tugged at the growth sprouting from its banks.

The Oubangui or Ubangi, the largest tributary feeding into the Congo River, is about eleven hundred kilometres long, roughly the same length as the Danube. Bangui is at a kind of elbow in the river. Go south from the capital and it widens till it joins the Zaire, east and it narrows and becomes the Bomu River. Fed up with bread vans, we would travel east by boat to the next border post. At Mobaye, the Oubangui was clearly too narrow for steamers or floating villages. Our journey would continue by way of something smaller.

After a third night sleeping with the centipede, I lowered myself gingerly into a hollowed-out tree trunk nestling in the reeds. Olivier passed me a bunch of bananas, some manioc (a sausage of pounded cassava) wrapped in banana leaves and eight tins of sardines. He had not been idle. The pirogue was about eight metres long, and instead of seats it had a few slats nailed in horizontally to lean stuff against. Three paddlers would take us to Limassa, a three- or four-day trip depending on the strength of the current.

The lean, coal-black paddlers wore baggy shorts and carried short paddles and long poles. They belonged to one of the several tribes living along the banks of the Oubangui — Bouraka or Riverain Sango or Yakoma or perhaps Dendi, I had no clue which. They spoke Sango. And presumably some French, too, although Olivier had arranged the whole thing with a French-speaking agent beforehand. The price for the journey had been agreed: CFA 4,500 ($18) each, payable on arrival in Limassa. Olivier had a letter from the agent to hand to a friend of his in Limassa. Everything seemed set. It was a thrill not to be continuing by bread van. This was my big chance to honk at the hippos. The thought of the new pace and with Mobutu and his soldiers gone from my mind, I began to perk up.

The first day went well. The crew poled like gondoliers. It was tough going for them. We were forced to hug the riverbank because it was early December and the current was strong after the rainy season. They poled expertly, their stringy muscles flexing with each thrust, finding the correct depth to make the swiftest progress: too close to the bank and the boat would be snared in the reeds and tangled roots, too far from it and they’d achieve two shunts forward, one slide back. Sometimes they carved a path through the rushes, our boat making a soughing sound as we ducked under the branches, leaned to right and left to avoid lianas trailing down like severed phone lines. I dozed, propped up against my rucksack. Olivier smoked. Glittering dragonflies sped about our heads. From time to time, we disturbed cranes or ibises, their broad wings spanking the rushes as, screeching in protest, they made their getaways. Pied kingfishers bulleted across our bow.

At midday, one of the crew jerked a fish out of the shallows on a bit of line he had tied to his wrist and wound around his index and middle fingers. We rode up on a sandbar, and the crew cooked it over a fire and ate it, sitting on their haunches. Oli and I stripped to our underpants, jumped into the river, washed ourselves and wallowed, keeping a nervous eye out for unfriendly wildlife. But nothing could be seen through the stirred-up waters, no hippo nostrils, no beady eyes of hungry crocodiles. I wondered about bilharzia; the blood flukes that carry the disease live in the lakes and rivers of central Africa, and apparently they like to burrow in through the soles of your feet.

I slept during the afternoon, woke up at dusk to the sound of beating drums. The trio were paddling now, pumping hard for a destination. Wind blew clouds of fireflies off the banks over the canoe, thousands of tiny sparks winking in front of the emerging stars.

The second day didn’t go quite so well. After a night spent on a kind of tray made of bamboo slats under a banana leaf awning in a tiny village, our progress upstream ended abruptly at noon. The crew had been paddling and poling lethargically all morning. Perhaps they’d had enough, hadn’t realized it would be this hard or had overdone it the day before. We were at Satéma, another village. Suddenly they turned ninety degrees, rode the boat smartly up on the beach and refused to go further. Surely, after a good lunch . . . No. That was it. They were done. Oli and I looked at each other dumbfounded. Maybe we should have got to know them better instead of flaking out yesterday. We should have appreciated their efforts. In fact, there had been almost no communication between us. We weren’t even sure that they spoke French beyond phrases like “allez-y!” Let’s go! Now we knew. They demanded their money. They said they had only agreed to come this far. No amount of persuasion or cajoling had any effect. Olivier tried yelling at them. This was not Limassa. They would not get a centime out of him till we were in Limassa. The noise we were making attracted several villagers, then a soldier.

We were led away to a hut like naughty school children and told to sit on a bench in front of his desk. Olivier, me, three paddlers in a line. The sergeant was clearly a quiet, firm man who took his duties as frontier policeman seriously. He had a head like a walnut, wore a faded khaki jacket with stripes on the sleeve and tightly laced black boots. I could tell that it would be unwise to upset him. He invited one of the paddlers to account for the disturbance. The man was halfway through his second sentence when Olivier jumped to his feet. Arms flailing wildly, thrusting the letter from the agent in Mobaye — now crumpled and blotched, but clearly marked with the word “Limassa” — under the sergeant’s nose. Oh dear. Wrong approach entirely. Again, the words of the South African oceanographer I had met in Sète youth hostel flickered across my mind: “Your progress will depend on your social skills.”

“ASSEYEZ-VOUS!” barked the sergeant, rising from his seat. I pulled Olivier down, told him in English to take a look over his shoulder. Door to a windowless room, the word “Cellule” chalked on it. He sat down, cursing under his breath. “Merde,” he said, and “fookmen,” his term for anyone he regarded as exploitative. The sergeant asked more questions, allowed the Frenchman to say his piece in turn — if he could do so in a civilized manner. After some deliberation and much to Olivier’s disgust, he decided that we would each pay the paddlers CFA 3,000 — two-thirds of the amount agreed on in Mobaye. We had no way of knowing for sure that we weren’t two-thirds of the way to Limassa, but halting midday on the second day of a trip supposed to take three or four did not seem to make us two-thirds of the way to our destination.

We all walked outside. The boatmen returned to their canoe and pushed out into the river, no doubt relieved to be rid of their load and running now with the current. Olivier scowled, raked his beard vigorously with his fingers, screwed up the letter and tossed it away. The sergeant’s face softened. He called one of the villagers over, asked him to put us up for the night.

We followed a mud path through the forest for half a kilometre till it came out at a little homestead overlooking the Oubangui. There was one obstacle on the way. A river of ants, three metres wide, three ants deep. Ten, fifteen thousand of them, and that was just on the path. A rippling tide of motoring legs and tapping antennae. I crept close, fascinated by the rustling noise they were making. Each ant was about a centimetre long, red-black and polished. Along the edges were soldiers, rearing up on their back legs, waving their bulbous oval heads, clipping the air aggressively with their mandibles. I had watched enough wildlife programs on TV to know that these were African driver ants. Caterpillars, grubs and beetles were held aloft, swept along, twitching and kicking in the current. I felt a sharp pinch on my leg, yelped and scrambled back, snatching off two guards clamped to my calf. Others were scaling my boot. If it wasn’t one kind of soldier, it was another.

The villager laughed. Kicking off his flip-flops and tucking them in his shorts, he backtracked along the path a little way, then sprinted forward and leapt. He appeared to clear the column ant free. Now our turn. With our rucksacks, we would have to try something different. Hop, skip and jump. Try and stay on our toes. Olivier put on socks and sneakers.

We arrived on the far side with half-smashed ants stuck to our soles, angry ants nipping our feet and ankles. We knelt and flicked them away. They — or their cousins — would take revenge on English naturalist and travel writer Redmond O’Hanlon as he explored the Congo a year or so later: “Panicking, I fumbled with the toilet paper, pulled up my pants and trousers (a bagful of ants fastened on my genitals) and ran from the hut, stripping off my shirt, running from the pain in my back.”

Another night on a wooden tray, then our third day on the river. Asking around Satéma, we managed to find two men with a pirogue willing to take us thirty kilometres further upstream to a place called Limbongo. Short of supplies, I gave a few francs to the younger man mid-morning and asked him to buy us bananas from a village we were passing. It was perched on a cliff five metres above us, yellow roundels with palm thatch roofs reaching to the ground, broad-leaved banana trees among them. It took him an hour not to do so. He came waltzing back down with cigarettes and a cluster of bare children milling round his legs. They had shaved scalps and navels like avocado stones. When they saw us, they shrieked and backed away. We smiled, waved and said hi. They went berserk, running this way and that, shouting, falling over, the smaller ones hiding behind the larger. We chuckled, shook our heads and shoved off. Watched them race up the cliff, tripping and stumbling and calling ahead to the village to raise the alarm. They disappeared for a moment, then reappeared with sticks and clods of earth and flung them at us.

In the afternoon, more kids, this time bathing in the shallows. They didn’t see us coming through the rushes, and by the time they did, we were bearing down on them, making ghoulish faces. Much to our amusement, this sent them clambering up the bank, bawling at the tops of their voices. Short-lived entertainment: five minutes later, there were four pirogues containing angry men with machetes on our tail. It was our turn to look horror-struck.

“N’arrêtez-pas,” I urged our paddlers. But we were losing ground. I looked for a weapon. Olivier’s flip-flops, a half-eaten stick of manioc wrapped in banana leaf, a Frederick Forsyth novel called The Devil’s Alternative that I’d been reading. In my bag, my pocket penknife with its two-inch blade. No. The mechanical pencil wouldn’t do, either.

“Bonjour messieurs. Comment ça va?” I got up, tried to exude bonhomie as they drew alongside, grabbing hold of our boat. Big smile. They stood up and began shouting, pointing back at their village, stabbing the air with their fingers. They spat accusations and waved their arms in Olivieresque rage. I feigned bewilderment and innocence, not understanding a single word they were saying, hands open and empty in front of me. The correct gestures would be important here.

“Est-ce qu’il y a un problème?” I nodded seriously, arms crossed, as they replied, puckering my face into a look of grave concern. Raised my hands when they’d finished in a despairing, what-can-you-do-with-them gesture. “Ah, les enfants, les enfants.”

Olivier remained seated during this performance, stroking his beard, uncharacteristically quiet. The men fumed on but had now turned to one another and seemed uncertain about how to carry the matter further. They sat down, talked amongst themselves.

“On y va,” I whispered to the paddler nearest me. To my surprise and enormous relief, they let us pull away. What had their children reported?

Ours was a quiet tree trunk after this. The encounter had subdued us, made us think about safety. Maybe having the odd soldier around wasn’t such a bad thing. It was hard to say just how much danger we had been in. This stretch of the river certainly seemed off the beaten track. We’d seen nothing bigger than a pirogue on it since Mobaye, and these kids hadn’t seen too many wasambye (“people wearing cloth”), as Sir Henry Morton Stanley was called by the tribes on his travels down the Lualaba River in the country south of us a hundred years before.

Certainly things had been more precarious for him. During his second expedition across central Africa (having located David Livingstone on his first in 1871), he wrote in his journal: “We have used all the diplomacy in our power to induce the natives to be friends, but it has been of no use. Two of my people went to purchase food. The natives sold food but in the meantime surrounded them and one of them threw a spear at Kacheche, who shot him dead.” Two weeks later, Stanley “came to a large party of natives 400 - 500 gathered on bank. They were fiercely demonstrative, but as we were only 8 in number we spoke them fair and patiently vowed we came on peaceful duty. We were answered with a flight of arrows to which we replied deliberately with Snyders and killed 3 and wounded several more, while we suffered no loss.”

We hunted around for another canoe in Limbongo. An old man said he could get us to Limassa. Another thirty kilometres or so, no more than a day’s journey. The old man did fifty strokes, then gave up, exhausted. That meant it was up to the lad he’d put in the bow to propel us. Four people and our luggage, against the current, without a helpful gondola pole. Olivier and I tried to wrestle the old man’s paddle from him. After a while, we pulled in. Fierce argument. No, we wouldn’t be paying CFA 2,000 for going around one bend of the river. We shouldered our sacks and strutted off into the forest.

The old man and the boy paddled off and I wondered whether we had made a sensible decision. We’d probably be okay if we kept the river in sight. There was no one around, but there was a well-trodden footpath. Hopefully it connected bank-side villages — places where we could buy bananas, a chicken. The path stayed by the river for ten minutes. Then it wandered off into the forest.

Five and a half hard hours later, we were “soofering,” as Bright would’ve put it. We lacked machetes and rubber boots. The jungle, a tangled, cloaking mass of trunks, branches, wandering roots, looping cables, bamboo fronds and fallen logs, crowded us off the path, tore at our packs, made us duck and crawl. Often we were ankle-deep in mud. Mosquitoes settled on us when we paused. We splashed on DEET. Sweat washed it off. No clue as to how near or far anywhere was, the river lost. Last tin of sardines gone, little sweet bananas in a plastic bag dangling from my rucksack turned to mush. Wearing sneakers and carrying a frameless rucksack with foamless shoulder straps, Olivier was in greater discomfort. He squelched along, lopsided and swearing.

Yet it was also remarkable to be swallowed like this, inside a living, breathing body of tentacular greenery uncoiling in all directions, growth winding around growth. Sometimes there would be no distinction in any direction — four towering walls and a ceiling of intertwining branches and leaves; in clearings, where the sun penetrated, light mined imaginary tunnels. Attracted to these clearings by a glistening mud puddle or a piece of rotting fruit were butterflies — flares of bright crimson or chrome yellow, lime-green with black veins in their wings, cream with orange wing-tips. Clouds of them, chevronned, eyed, ribbed and dotted with colour, eddied over their target. A praying mantis and a butterfly wrestled at the end of a stalk leaning over the path, the mantis mauve with pale translucent legs and claws and a curious yellow and green eye marking the thorax. I’d seen plenty of mantises in Japan but none as flamboyant as this. It was hard to imagine that a couple of weeks earlier, on the same land mass, the scenery had been the opposite: monochromatic wastes, no life in sight, an unblocked sky, a relentless sun. I felt at times that our path would lead us to a glass door and that we’d slide it back and step through, leaving the tropical turmoil behind, the sauna air, and return to reality.

Villages materialized, sudden gaps in the canopy, splashes of sunlight on eight to ten huts. At one, a man picked oranges for us from a tree outside his hut, a delicious dwarf variety that squirted our faces as we bit into them. He invited us to stay for dinner. Before we could reply, he disappeared into his hut. I thought he was bringing his son out to meet us, a little boy who seemed singularly reluctant to go anywhere, held by the wrist, head dipped, his feet dragging in the dirt. This was dinner: a black monkey with a bullet hole in its head, congealed blood streaking the fur, pink wrinkled face, eyes glazed. We’d need to be a little bit hungrier.

The path snaked on. Light ran out. No Limassa. Another small village. Tired and sore, we asked if we could pitch our tent there. Twenty-two people including eight infants gawped at us. The nearest man had a goitre the size of a football bulging from his neck. He took deep breaths, and it vibrated each time he exhaled. One of the babies wriggled and kicked and fussed in his father’s arms. An old man with a milky eye said, “Bienvenue.” Three giggling teenage girls dashed off and returned with two bamboo chairs. We sat, wondering what would be expected of us. The village sat, squatted, sprawled or knelt in front of us. We were visiting royals. Darkness fell. A fire was lit. If only one of us could juggle or tell a wonderful story in their language.

“Est-ce que vous avez un poulet qu’on pourrait acheter?” I asked the old man; Olivier and I were famished. Could we buy a chicken off them? We could hear squawks.

It was brought before us, wings thrashing the hand that held it. Could they perhaps bring it back in pieces on a mound of rice? After an hour’s wait, we tucked into the finest meal we’d had in the Central African Republic. Our subjects nattered to one another as we gnawed the bones and shovelled down rice with our fingers. Fortunately, it was too dark for them to be appalled at our far-from-royal table manners. We keeled over shortly afterwards beneath a lean-to on a pair of stick cradles which we clothed in mosquito netting. We paid well for our meal in CFA, but again I regretted not having handy items from Britain to hand out. I tried to imagine what uses they might put nail scissors and tweezers to, how they might respond to a fashion magazine, what interest a box of crayons and a pad of paper might bring.

We never made it to Limassa. Mid-afternoon the next day, we stumbled out of the forest onto a main road (as main as they get in C.A.R.), legs spotted with bites, daubed in mud. We collapsed on the road, then sat cross-legged and waited for something to happen. A bread van crammed with bodies, roof piled high with luggage, came rumbling towards us, wobbling from side to side. I had never been so glad to see any conveyance.

“Zis autoboos will carry us to . . . somewhere,” Olivier said cheerfully, smoothing down his beard as he got stiffly to his feet. We climbed up into the cab and sat with the driver. Destination: Kembé. Another village a little further east on the river. Another possible entry point into Zaire. Bangui, Mobaye, Limassa, Kembé. Was Kembé still Ubangi du Nord? The driver’s radio trilled out a song, a jaunty, jogging rhythm that I’d heard a lot in Cameroon. Inventing our own words, we sang along.