Don’t ever try to cross an ocean on a small boat. It is a nightmare experience that you may not survive. Nothing stays still — not even the horizon. Everything is on the move all the time, 24 hours. There is no escape. Can’t even go to the toilet. In fact, that’s the worst place to go. It’s below deck and once you’re below deck, you’ve had it. At least above deck it seems as if you have an alternative: you can just hop off and drift away in the boat’s wake when it all gets too much. Below deck, you’re stuck with creaking, sliding, clattering turmoil. You lurch and stagger around like a drunk and everything is difficult to do, even getting a glass of water. You need two hands – one to hold the plastic mug, the other to grip the sink while you balance on one foot. With the other foot, you must pump the water into the mug. Some will tell you that if you’re at the helm, you’re fine. Don’t listen to them. Everywhere on the boat is on the move. Constantly. There’s no escape.

“Want another suppository, Tony?” The sun was out, clouds raced by overhead, the waves were still huge and crested. Mike stood at the helm, wheel slipping loosely through his fingers, wind ruffling the hair around his ears. He hadn’t been sick. In his RCYC golf shirt with the collar turned up, cap and sunglasses, he looked uncommonly healthy, far too relaxed after the disaster of the night. Obviously his wife wasn’t up yet.

I was crumpled up like a fetus on the starboard cockpit locker. I had been there for three days and three nights, with brief excursions to the helm and to the heads. I stared at him through crusty eyes. My hair was gluey, my skin gummy, my fingers numb, my throat dry and painful. There was a foul taste in my mouth and I was thirsty.

“Maybe I better had,” I croaked.

“Run and fetch him one, Warren, there’s a good lad.” Warren bounded down the companionway ladder. He hadn’t been sick either. He returned a moment later rolling one around in his palm. White and torpedo-shaped, an unpukable seasickness pill. I snatched it from him and, while he watched with keen interest, stuck my hand down the back of my pants. On my wrists were acupuncture bands. “At last, a solution for the miserable mariner!” the box had bragged.

“You know, having a clean mouth works wonders,” Mike said. Just wait till Glenda got hold of him. She’d almost hit him last night. Warren brought up my toothbrush, some Colgate and a mug of water. I looked at the speedometer beside the companionway hatch. Remarkably, Milkwood was doing seven knots.

Yacht Milkwood was a Beneteau 345, an eleven-metre French-designed cruising sloop — one mast, two sails — white with burgundy trim. Now we had one mast, one sail. There were seats along both sides of the cockpit and another behind the wheel with blue waterproof cushions on them; two of these cushions had been washed overboard. The wheel was mounted on a pedestal with a gimballed compass in the top, a limp rubber band connecting it at the base to an inoperative self-steering device we called “Fred.” A burgundy spray dodger with Plexiglas windows protected the cockpit. At the stern, there was a man-overboard ring shaped like a toilet seat with a buoy and flag attached, a barbecue grill, the radar apparatus and a wind generator. A surfboard and fourteen thirty-litre jerry cans of drinking water and gasoline were bungee-corded in a row to the guardrails on either side. Each had a piece of ripped tartan shirt under its cap to stop it from leaking. They slid about moaning as Milkwood heeled and pitched. Upside down and strapped to the saloon roof was a fibreglass tender, and folded up in the forepeak locker was a “rubber duck,” Mike’s inflatable dinghy. Mooring fenders tethered to the rails dangled over the sides like monstrous suppositories; they should have been brought in and stowed right after we left the slip. The Atlantic kept reminding us to put them away by tossing them on deck, where they rolled about declaring themselves before disappearing back over the side. I was definitely at sea with amateurs.

“Rocky-rolly stuff,” chuckled Mike. He was forty-two, but with his boyish good looks and chirpiness he could have passed for twenty-six. A hairdresser from England, he had jumped aboard a Southampton - Cape Town liner in 1973 because it was short a barber. Twenty-one years later, he was married to a Boer and had two kids, a house overlooking Hout Bay, down the coast from Cape Town, and a yacht. Glenda was a travel agent with a somewhat blunt Teutonic face that needed a smile not to seem severe. Her dark brown hair, tinted red, was gathered at the back. Warren was a skinny boy of eleven, a miniature version of his dad, Tamsyn a blond, boisterous five-year old. The Smith family had not been to sea before. Mike had just completed his skipper’s course, Glenda a few lessons on being a deckhand. Glenda’s mother, who had visited the boat daily during preparations, had been beside herself, sobbing uncontrollably, full of What are you going to do if . . . ? questions. Mike disposed of each with a brief and unqualified sentence like, “Well, we’ll just radio for assistance and sit tight.” To her mind, what we were about to do was suicidal. The ocean would swallow us without a trace, and to think that two youngsters were being taken to their doom!

“Tony’s ripe,” Glenda said sticking her head out of the quarter berth window. I sniffed myself. Green stains of varying shades adorned the white tracksuit pants Mike had lent me. One large one was distinctly avocadoish in complexion. Others were of a darker hue. Shouldn’t have had that final cottage cheese and avocado sandwich on the quay, I guess.

“Bile,” said Glenda, coming up the companionway. She’d been sick, too, but seemed to be over it. Keeping my eyes locked on the horizon, I tentatively peeled off my clothes and threw a bucket of seawater over my head.

“Michael, I’d like a word with you.” Mike stiffened. I slid across and took the wheel: we were heading 310° to St. Helena, an island fifteen hundred nautical miles away. Like a naughty boy called to do homework, Mike ducked inside.

We’d had rough seas out of Cape Town, although I’m sure, given the reputation of the spot, they could have been much rougher. Mike had promised that Fred could help us out, be a stalwart third helmsman who would give us the chance to catnap, make tea and find our sea legs. But Fred seemed about as able a seaman as myself. Perhaps the belt connecting him to the wheel was too tight, or maybe it was too loose. Maybe the autopilot wasn’t mounted the correct distance from the wheel. Whichever, we punched in 310° and five minutes later, Milkwood was veering off in a new direction, sails back-winded, Fred bleeping hysterically.

“Waves must be too big,” said Mike breezily, disconnecting him. So then it was the two of us alternating watches, three hours on, three hours off, day and night. The sleep I got was fragmented by the punch of waves against the hull, splats of spray finding a way round the dodger, and the odd swamping. I am a sack of spuds, I remember telling myself, as I released my sleep-denying iron grip on cushion and locker clasp. I must rock and roll with the waves. Five times I was rolled off my locker seat onto the deck. In my brain, a quote from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar repeated itself: “We must take the current when it serves, or lose our ventures.” This little boat would carry me to a new continent. Like the beast of the Sahara, it would rough me up, but here and now was the chance to cross roadless wilderness. Seize it lest the door close.

More alarming than Fred’s refusal to steer was our busted boom. It lay inert across the deck like a fallen branch, wrapped in the mainsail, bound and secured by ropes of varying name. It was a relief to me (albeit a minor one) that I had not been the cause of this wreckage. The skipper had been on watch at the time, and for some reason I was below deck. Glenda and the kids were asleep. Somewhere between midnight and three, a loud crash caused the whole boat to shudder. Then there was the cracking sound of loose canvas flapping in the wind. Another crash.

“Michael?” Glenda.

“It’s . . . it’s okay. Wind’s playing up.” More angry flapping, a third crash and shudder.

“MICHAEL! What’s going on?”

“Er, won’t be a second. Almost have it under control now.”

CRASH! Shudder. This was like travelling through Nigeria on the night bus.

“The whole boat’s . . .” Another crash, followed immediately by an ugly snapping sound and a thud on the roof, as if we’d been hit by a meteor. We raced up on deck, ready to abandon ship, Warren in his pyjama bottoms, Tamsyn screaming “Mummy,” me suddenly liberated from thoughts of my mutinous stomach. There, a view of the stars where a large triangular sail should have been, a baffled hairdresser holding a limp rope in one hand, a jib sail flapping wildly out front, the boat drawing to a halt. The rope was attached to the boom and the boom was no longer where it should have been, suspended two feet above deck. The snap had been the gooseneck, the thud one end of the boom hitting the saloon. Unsupported, the mainsail had slumped but still clung to the mast in places where the sliders had not been torn from their track. The wind teased its sagging folds.

“Oh, Michael.” Glenda put one hand over her mouth, horrified. He’d just turned Milkwood into a floating coffin.

“N-not to worry. We’ll just, er, roll it up and . . . and run on the jenny.”

“Just put the sail back on, Daddy,” said Tamsyn after a moment’s silence. Glenda herded the kids back to bed. I helped Mike lower the boom and gather up the main. R.I.P. I would later find out that he’d been gibing: the wind coming directly over the stern caused the boom to flick violently from side to side. We inspected the remains of the bracket in the morning. Nothing could be done. It had been ripped clean off the mast, bolts gone, a repair job for a boatyard.

For two days, we made good progress sailing on the jib — or jenny or Genoa. Even I could work it. Release the jib-reef — the thin stripy rope cleated to the saloon roof. This goes to the spring-loaded drum at the foot of the sail. Unfurl the sail by yanking on the jibsheet on the port side — the wind was coming from the east or southeast. Loop the sheet once or twice around the winch, yank some more, then wrap it around completely, take a winch handle and crank it in. The amount of sail you put out depends on the strength of the wind. The amount of yanking and cranking you do on the sheet depends on where the wind is coming from. You have to watch the tell-tales on the sail edge. Bud had told me about these, the little ribbons that flutter horizontally when the sail fills with wind correctly. Fine-tuning the sail to get the tell-tales horizontal is called trimming.

We became affectionate towards jenny, a new acquisition, brilliant white with smart burgundy border. She was precious, our only means of wind propulsion. We had to look after her, check that she was content, constantly bloated with wind and never flapping for long when the wind changed direction. There was no doubt that this sail was a flimsy extra. What if she ripped free and abandoned us in a gale or tore or dropped to the deck like her big brother? Weren’t we screwed then?

“What if she rips free and abandons us in a gale, Mike?”

“No need to worry, Tony. I’ve got a spare sail or two tucked away. Somewhere. Spare main, anyway. Can’t remember if we chucked out the old jenny or not.”

Could our engine carry us on to our destination? No. We could motor five hundred miles with the fuel we had on board, but that was it.

It was with initial dismay then that I awoke on the sixth day to find jenny asleep. She resembled a drawn stage curtain. I looked about. After all the chaos and madness of wind and wave and spray versus small fibre-glass vessel, silence. Suddenly Milkwood was resting on a vast swimming pool before opening time. Unagitated, inviting blue liquid, sparkling benignly in the sun, stretched out to the horizon. Shading my eyes with one hand, I looked in every direction. Just us here: one solitary upturned beetle denting the surface. Then I realized I felt fine or nearly fine. My stomach was calm. I had fed it salt crackers, Cup-a-Soup, sugary black tea and mints the last two days. Now it appeared less annoyed with me. I could balance and walk, too, without tottering, although my legs did feel weird.

Mike put the stern ladder down. It was time to test this swimming pool. Throwing off my clothes, careless of what might lurk in the depths below, I hurled my gummy, battered, vomit-streaked carcass over the guardrail. The Smiths followed, with the exception of Glenda, who was afraid of being eaten by a shark. The kids were ecstatic, desperate for this new and unimagined freedom. Screaming and shoving each other, they dived in, climbed out, somersaulted in, climbed out, jumped in forwards, jumped in backwards, cannonballed, doggy-paddled, splashed and chopped water at each other with open palms. I front-crawled vigorously around the yacht, away fifty metres and back, then breaststroked under it, feeling my aching, knotted, stressed body unravel.

Oh, yes, yes, yes, yesss! I surfaced winded. Mike threw me a snorkel from a cockpit locker, asked me to look about for “unfriendlys.” Bit late for that, I thought. I put on the mask, bit the end of the pipe, blinked and looked around. Shafts of sunlight spearing down into the inky gloom. I watched one shaft probe tentatively, then pull up sharply, probe again deeper, pull up — as though nervously testing to see whether something massive and dangerous was sleeping down there. I looked at my pink legs kicking. Bait? There could be as much as five or six thousand metres of seawater below. Home to what? Surrounding me in suspension were blobs of plankton, brown and translucent. Not a fish in sight. I swam to Milkwood, ran my hands over her hull, discovered a yellow-brown minnow playing around the rudder. I wondered whether it had been with us since Cape Town.

It was like this on the seventh day and on the eighth day and on the ninth. We folded down the spray dodger, we hung our seawater-sodden clothes out on the rigging to dry, we soaped our bodies down with liquid dishwashing detergent (it lathers in seawater), we bathed. We lay out on deck and read. I could write an entry in my journal. We stowed the mooring fenders. We remained becalmed for ten days as we approached and crossed the Tropic of Capricorn.

Some weak winds did shake jenny from her slumbers in the evenings, but to make headway we had to turn the engine on. Two or three hours each evening also recharged the ship’s battery. Shame we couldn’t use the wind generator to literally generate wind. This thought reminded me of an embarrassing question asked by the pretend sailor shortly after meeting his captain-to-be. We were in a borrowed van shifting boxes from the Smiths’ house into storage. Mike was listing the equipment on his boat.

“. . . life vests and flares, solar panel and wind generator . . .”

“Wind generator? To blow wind in the sails when there isn’t any, yes?” He turned as if seeing me clearly for the first time. No. Actually, a propeller on a pole at the stern that turns into the wind, spins and makes electricity. Having assured Mike I was an able seaman, once a sea cadet, I almost blew my cover with that display of marine ignorance.

During one swim, we noticed a pair of fish circling the boat. Nearly a metre long, we reckoned, yellow, lime and silver, with beady eyes regarding us cautiously from unfishlike heads — not tapered to the nose but blunt like clubs. Make good eating, Daddy said, which caused the kids to go rummaging in my cabin for their fishing rods. And it didn’t take long for their two lines to get tangled up and a fight to commence. The fish continued to circle unperturbed and remained with us for three days, not a difficult achievement at the speed we were travelling. Dorado or dolphin-fish, according to a St. Helenian. Mike was right — they would indeed have been good eating.

My berth was the worst on board: the forepeak cabin, the rocky-rolliest part of the boat, right beside the heads. Only the anchor was further forward. But now it was still. Off-watch, I dozed in there with the hatch open, gazed at the sky, azure by day, star-freckled by night. I thought back over my time in Africa. Like Ted Simon, I had stayed on the ground, swallowed the bugs . . . but had I really extrapolated from the dust? Had I looked closely enough, looked left and right as well as straight ahead? Almost certainly not. For sure, five months could have been spent in just one African country, learning something new every day. Without doubt, I had missed a lot. On the other hand, I had touched on plenty. I had got an idea of “size and variety,” of “the relation of one country and one culture to another which few people experience,” as Michael Palin put it, reflecting on his eighty-day circumnavigation. And what a heady ride! I had the feeling that I had surfed a wave, wobbling precariously, barely keeping my balance, afraid, the wave in control, falling off my board a couple of times, helped back on, somehow riding it to shore — Table Mountain. How would I ever assimilate all that had happened? And how odd to have roamed far and wide across a continent and now be on a floating platform without room enough to swing a cat.

As Milkwood crept north, the wind gradually picked up. Jenny filled and gave us three, then four, five knots. We established routines, settled down to regular mealtimes. Glenda was queen of the galley, Mike and I and occasionally Warren her washing-up wallahs. I could now go below deck for short periods of time, longer if horizontal. Each morning began with Cornflakes and U.H.T. milk, a jam sandwich (while bread lasted) and tea. We had tuna or processed cheese or tinned luncheon meat sandwiches at noon. Then stews or pasta or rice dishes with fresh or tinned vegetables for dinner. Tinned peaches and pears, chocolate or vanilla flavoured mousses for desserts. Gingersnaps, dried fruit, biltong (South African beef jerky) and granola bars as snacks. The kids had their own private stashes of potato chips and candy that they were cautioned to make last to the first island. Tamsyn finished hers within the first week and begged more from her brother. I found myself keeping an eye on the time, day and night, looking forward to each meal, knowing roughly the hour it would arrive. I was no longer in control of my diet, could no longer eat whatever took my fancy whenever I chose. I definitely could not pig out. Over the side was a desert of sorts, and we had to live on what we carried and ration it till landfall.

Night watch demanded a special treat — especially on the midnight-to-six shift. Mike and I had decided that three hours on, three off through the night just meant we were persistently tired and cranky. Fred still wasn’t interested in lending an electrical hand despite being painstakingly dismantled and rebuilt, per the instruction manual, so we switched to six on, six off. That way, we could at least get half a night’s sleep. Without Fred to cover for me, I had to dash to the galley at three a.m. for a revitalizing jam sandwich and coffee from a Thermos made up after dinner. Without the booster, I tended to nod off over the wheel. Down in the dark, I spread the curds of raspberry jelly generously over the bread, listening for any sounds that said we had strayed from the course. Sometimes I was slow. “Tony?” A snapping jib or smacking waves would rouse Mike from his light sleep, fearful that a snap was a tear and that we were now indeed in a floating coffin.

I enjoyed night watches. For the most part, steady warm wind gusting from the side or rear, a gentle rhythmic swell lifting the boat, setting it down. On cloudless nights, I had little need of the compass. The mast split the heavens ahead, and I steered by keeping a pattern of stars to either side. A time for wonder and wandering thought, standing there alone in silence for hours, looking up, just the hull swishing aside the water, the odd clink of cutlery in a galley drawer below. I had never before appreciated the vastness and depth of the night sky. At sea, you get it all, without interruptions, without city glare. Stare at a patch between two bright stars, and the dimmer flickers in between suck you into a distant field beyond. On overcast nights, the world has a padded roof, and somewhere in that roof, a bulb emitting fuzzy light, flicking on and off, silvering the edges of clouds. Silvered clouds could be monstrous, many-decked spaceships till they merged and became a reclining cat from the Serengeti, paws outstretched, Milkwood’s mast scratching its stomach.

In 1994, believing that a little plastic box the size of a pocket calculator could enable us to hit an island eleven kilometres across, twelve hundred nautical miles from the mainland, was tricky. How did it work? Switch on, raise the thumb-length antenna, hold the box up through a hatch for a few minutes and . . . bingo! Signals from satellites gave you your position, free of charge, so many degrees longitude, so many degrees latitude. Unroll a chart and make an x. What could be simpler? But how did the Global Positioning System really work? I hadn’t the faintest idea. It belonged to the realm of things I would never comprehend: electricity, black holes in space, telephones — how can my Japanese friend’s voice, half the earth away, sound as if it’s right next to me?

“What happens if the G.P.S. fails, Mike?”

“Um, it won’t. I’ve got replacement batteries and it’s designed to float in the sea . . . and we have a sextant aboard . . . and I did a bit of study on my Skipper’s Course on how to use it.” My ongoing existence appeared to rely on a triangular piece of cloth suspended from a wire and technical wizardry that I could easily sit on and crush or the kids could use as a Star Trek walkie-talkie till the antenna snapped off.

After nineteen days at sea, we saw a stumpy brown rock that looked like something you didn’t want in your shoe pimpling the flat horizon. It took a long time to grow into a heap of rocks, then an island with contours and signs of habitation. We arrived after dark, seventeen hundred miles of ocean crossed. We were stunned. We’d made it, without having to fire off any signal flares or eat the weakest members of the crew. How had we managed to do that? On a little bitty sail, too. We congratulated each other, we shook hands. White shore lights and the smell of earth beckoned, but we hung off till dawn, scared of going close lest we hit something. No one slept.

St. Helena Island is British territory and has been since the English East India Company took possession of it in 1659, although it was discovered over a century before by a Spaniard called Nova Castella. The first inhabitants were employees of the company and their slaves from Goa, Madagascar and the East Indies. Edmund Halley visited in 1676 to observe Mercury and Venus and map the constellations of the southern sky. Napoleon Bonaparte came here under heavy guard in 1815 after his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Expecting a rescue attempt, English soldiers built fortifications, installed cannons and garrisoned the island till the general’s death in 1821. At Longwood House, where Napoleon was detained, you can see his dress shoe, a lock of his hair and his tomb. The tomb is now empty, Napoleon’s body having been reburied in Paris.

Mining town, I thought, as Milkwood angled in towards Jamestown in the northwestern corner. Bare brown cones of rock like slagheaps devoid of life to either side. A dead zone. Volcanic, obviously. Did anything grow here? I looked at a map of the place. Some parts of the island had distinctly barren names: Deadwood Plain, Bonfire Ridge, Stone Top Bay, Dry Gut Bay, the Gates of Chaos. Not that I was at all disappointed. I didn’t need it to be lush and palm-treed. I was dying to set foot on land, any land. Ready for two or three cold beers and a Wet Gut. Ready for a long, leg-enlivening run.

“St. Helena Port Control, this is sailing yacht Milkwood, over.”

Our first contact with the world in nineteen days, the Smiths having only VHF radio with a range of twenty nautical miles on board. We dropped anchor near several other yachts. Customs and Immigration came out in a launch: £16 port fee from Mike, £10 visitor’s tariff from Glenda and me. A little steep for access to a barren mid-ocean rock, I thought, teasing a ten-pound note out of my money belt. Olivier wouldn’t have been happy. Milkwood could not be moored at the quay, we were told. No room. We should stay anchored where we were and ride to shore in the shuttle service provided (£1 per person per day). “Just hail it on Channel 14 or wave at it.” St. Helenians were used to squeezing visiting yachties for revenue, then. Without an airport, their only other source of income was the tourists who came ashore off the Southampton - Cape Town liner once a month.

It was a damp, overcast morning as we took the shuttle to town — the island’s only town. I stepped ashore, thinking I might just start running with glee. Solid land, oh yes. But something was terribly wrong. I felt dizzy, I felt sick. I tried to walk. What was this? Three steps forward, one lurch to the side. Did they have different gravity out here? I was an astronaut, the ground rearing up at me. Was anyone watching this performance? I balanced on the five-metre-wide harbour front, trying not to fall off, the sea to my right, a dry moat to my left. Several rusty cannons pointed out from notches in a wall beyond the moat.

If St. Helena was British, maybe I could gorge on McVitie’s chocolate digestives or Mars bars or Walkers crisps or malt loaf. I began staggering more assertively, salivating, up Jamestown’s main and only street. There were brightly painted stone houses to either side. Blue, white, yellow, green, bold contrast to the dead brown of the island. We will endure on this ledge far away from land, they declared. A small hotel, a savings bank, police station, church, a little library, another hotel, a café called Dot’s, two bakeries with homemade loaves of bread stacked on wooden racks, a sweet shop with gobstoppers and licorice in tall glass jars. There were Morris Mariners and Ford Cortinas parked in the middle of the street. I felt as if I’d been time-warped back to my childhood. I would stuff my face with sweeties, then head home in Dad’s Mariner. I found the grocery store, the five - pound note in my pocket burning a hole. Oh, joy of joy, Bourbon Chocolate Creams and refrigerated Granny Smith apples. My hands trembled.

A teenage girl in a blue and white checked uniform operated the cash register, a punch-in-the-price-pull-down-the-arm antique. She had a square jaw, flat nose, hair that began straight then changed its mind and turned frizzy, sparkling blue eyes, lovely toffee skin I wanted to lick, big bounteous breasts. She smiled at me. I was in love. Two rows of glorious gleaming teeth. I fumbled with a brown paper bag for my biscuits and apples. That uniform. Back to a dim past of running errands to the corner co-op.

I sat on the steps outside and crunched my way through twenty-four Bourbons, the entire packet, while watching the activity around Jamestown’s only roundabout. It was where the main street leading up from the sea split into two roads, more a white blob than a roundabout. One road led away from the vegetationless shoreline and wound off, clinging to a barren ridge, towards a greener interior. So, my first impression had just been of the walls of the fortress. I would unpack my running shoes and go to where the plants grew just as soon as I had unpacked my shore legs. I bit a large chunk out of one of the Granny Smiths, chewed on it vigorously, moving it around my mouth in an attempt to rid my teeth of the chocolate paste that coated them. Then I joined the other yachties at Dot’s and listened to comparisons of the crossing while eating fishcakes.

We spent a week on St. Helena. Mike inflated the rubber duck and we used that and the fibreglass tender to go to shore rather than the shuttle, the big Smiths and myself in the duck towing the little Smiths behind in the tender — an amusement for them equal to a ride at the fairground. Daily dunks in the open-air swimming pool at the waterfront threw Warren and Tamsyn into the company of local kids who compared their molasses skin to the Smiths’ freckled white with hoots of laughter. A swim cost 36 p. Daddy put Warren in charge of the ten -and two - pence coins. Sometimes they got in for 34 p. and 26 p. or 36 p. and 32 p. I preferred to swim in the bay around the yachts. I also ran till I reached trees, read a novel about a psychopath that I found in the library, ate a lot of biscuits and climbed a flight of seven hundred stone steps called Jacob’s Ladder to the side of town. It was good to do just as I pleased when I pleased, wander in any direction, find lone spots and sit. I thought about Milkwood, the Smiths and the sea.

Sailing across an ocean was a disorienting experience, but it was a liberating one, too. Cleansing even, with the sudden severance from all that had defined my world for twenty-nine land-bound years: lawns, exhaust fumes, TV, daily showers, police sirens, points of reference, bus stops, billboards, bike rides, balance. Life was radically simplified: sea, sky, boat — that was pretty much it. Release from hurry, schedules and hubbub, great unpeopled expanse ahead without paths to follow or boundaries to negotiate. Roam at will, take as long as you want, nothing and no one to disturb you. No closing time, no one else to heed except those you sail with and other boats near shore. No marks of previous passage, often no signs of life but for flying fish shooting off wave tops and phosphorescent plankton in the ship’s wake at night. You feel like a pioneer carving a path of your own, an escapee freed of territories and rules and the teeming masses vying for ground.

But sailing on a small yacht is also a jail sentence in a cell the size of a Japanese apartment shared with four other salty-skinned people on rations, two of them youngsters. No escape except into a cabin where you can only lie down. Patience is mandatory, and you’d better like whom you’re going to sail with before you untie the mooring lines and stow the fenders. I was lucky. I got on well with the Smith family from the start. Glenda could be stern at times, but that helped when the children ran riot. Tamsyn’s banging out tuneless tunes on her portable piano had to be rationed to half an hour. Warren’s casting of his fishing line into the wind generator on the next leg wouldn’t be appreciated by Mummy, who would have to climb the pole again and cut it loose with a kitchen knife. Daddy yelled at Warren and Tamsyn when they hung like vervets from the rigging. I threw a bucket of seawater over Tamsyn’s head one day for staring at my penis while I was washing. But kids created diversion, too, breaks from the tedium on slow days when the wind was steady or still: drawing pictures, telling stories, learning to tie knots, playing Battleships and I Spy, singing songs.

Of course, all of this would be different on a bigger boat, say a kilometre long, made of steel, standing ten metres above the water and travelling unerringly at twenty-five knots on autopilot. Sea legs not required, sleep as sound as at Albergo Backpackers. Thank heavens I had taken the opposite. I had got a taste of the sea, felt its moods, got an inkling of what it was like to live day and night on its surface, subject to its every stir and frolic. No doubt it had many more tricks up its sleeve to show me.

“Tony, think I’ll take the kids off in the rubber duck to snorkel round one of the wrecks,” Mike said one afternoon. “Wanna come?”

There were two wrecks in the harbour, one the Witte Leeuw, a Dutch ship sunk by a Portuguese carrack in 1613. I was still digesting my lunch. The dinghy buzzed off, brother and sister squabbling over snorkels. I swam over an hour later. As I wove my way between anchored yachts towards the pair of rusted orange twists of metal poking out of the water, I became perplexed. The more obvious of the wrecks was clearly here, a blurry split oblong disintegrating on the bottom seven or eight metres below me. But where was the dinghy, where were the Smiths? I grabbed a flaking mast spreader and looked around for snorkel pipes. None. But some way to my right, three people, two small, one large, hung off someone’s anchor chain. I swam over.

“Mike?”

“Haven’t seen the dinghy, have you, Tony?”

“Thought you brought it with you.”

“Tied it to the wreck. Now it’s gone. Think someone’s nicked it.”

I swam back to the wreck and turned full circle, looking carefully at the coast, then out to sea. A grey sausage was nodding in the waves a couple of miles away. As far as I could make out, it was empty. I swam back to the Smiths.

“Daddy, my arms huuuurt.” Tamsyn.

I delivered the bad news. “It’s on its way back to Cape Town.”

“Bugger. Knot must’ve come loose. Never mind. We’ll have the shuttle pick it up.” That’s what I liked about Mike. Unflappable. Problems, other people’s doubts, dangers just bounced off him. He had a book on board called Happiness Is an Inside Job. “Each one of us must march bravely to a personal drummer, climb our personal mountains,” John Joseph Powell says on page 79. Mike’s personal mountain was to get his family to the Caribbean before hurricane season — without mainsail or dinghy if necessary, without dwelling on the pickles he got himself and his family into. He marched bravely and cheerfully, rarely missing a beat.

We swam for five minutes to a yacht nearer the jetty, knocked on the hull, shouted ahoy. No answer. I climbed the anchor chain and let down the stern ladder. Mike and the kids climbed aboard, and we began jumping up and down, waving frantically. After ten minutes, the shuttle spotted us.

“You stay with the kids while I go and get the duck,” said the hairdresser. It took about half an hour, and I wondered what I’d say to the owners of the yacht if they returned. Neither Warren nor Tamsyn seemed especially distressed. They were quiet for a change, though, disappointed perhaps that they weren’t involved in the rescue of the duck.

Mike untied the duck from the stern of the shuttle and waved at the man behind the wheel. “Cost me ten quid to get the bloke to go out that far,” he reported with a giggle as the kids climbed in. I said I’d swim back. I wasn’t there to witness Glenda’s reaction. No doubt Tamsyn provided all the important details.

On April 27, my thirtieth birthday, the Smiths had a special treat for me. I had wanted the full romantic package, including deck swabbing. “We’re on the island for the day. Clean out the bilges, would you?” Far more romantic than deck swabbing or cleaning the heads. First, lift the floorboards in the saloon and cabins and take out all the cartons of U.H.T. milk, juice, desserts and whatnot stored down there. Next, with a sponge or cloth and preferably wearing rubber gloves, get down on your hands and knees and mop up the viscous soup of seawater, spilled milk, food crumbs, hair and galley spills that the bilge pump has found too mucilaginous to evacuate. Squeeze into a bucket. Note interesting bouquet. Wipe away the remaining layer of slime coating the fibreglass. Also wipe away the gunk sheathing the bilge pump. Then return all stores to their rightful positions, wipe and replace floorboards and try to stand up. Demand a beer from the skipper, who has just been to see Napoleon’s shoe with his family.

The ship’s master raised a floorboard and surveyed the work with a critical eye. She nodded.

“There’s an R.A.F. base on Ascension,” Mike said on the day we left St. Helena Island. “One of the mechanics there will fix it for a coupla beers.”

I looked at the boom bracket. It was still dangling from the mast. Then back at the skipper, who was polishing his sunglasses. Then at Glenda, who was staring at her husband. Even Warren sensed that we were sticking our necks out. So, it was to be seven hundred nautical miles more on the jib. No mainsail. No autopilot, either — no one had taken Fred aside for a pep talk.

The easterly trades took a week to blow yacht Milkwood on a course of 310° northwest to Ascension Island. The winds were steady and consistent, neither too brisk for the boat nor too feeble. On the sixth evening, we noticed the island off our starboard bow. We were below our rhumb line. We had to make a sharp turn. After easy days with the wind at our backs, we spent a hard, bumpy night clawing north, waves butting the boat and making it lurch. Glenda and I were sick.

Ascension Island is an extinct volcano more desolate than St. Helena. Owned by the British, shared with the Americans, it is a mid-ocean military installation. Yachts were allowed to stop for only forty-eight hours unless they had an emergency. A busted boom and fallen main sail qualified. Mike was right: a man with welding gear and know-how fixed the boom bracket. Surprisingly, we got permission to linger for a full week to do repairs. This gave the kids (and big kids) opportunity to raid the American base for burgers, fries and sickening chocolate drinks called Yoo-Hoos. We got to play pool and watch The Fugitive on their seven-by-ten-metre outdoor screen. On the shore, we had time to get acquainted with Chelonia mydas.

I had been wondering what the large dents in the sand were, and the long trenches leading up to them from the sea. The little Smiths were not capable of such excavations. After a barbecue on the beach one evening, we met the diggers. Broad tiled backs, blunt heads, black eyes, snapping sand-crumbed beaks, paddling arms, painfully ungainly on land but, no doubt, powerful swimmers in the sea, judging by the capacity of the flippers to fling away sand. A metre and a half in length, apparently two hundred kilos or more in weight, the green turtle swims from Brazil every three or four years across thirteen hundred nautical miles of ocean to lay its eggs on an island fifty-four kilometres square. Without carrying a G.P.S. In the light of our flashlights, we watched one claw itself up the incline, pausing often, straining its neck forward. The green turtle, now an endangered species, used to be caught and kept in ponds on the island as a source of fresh meat for passing ships.

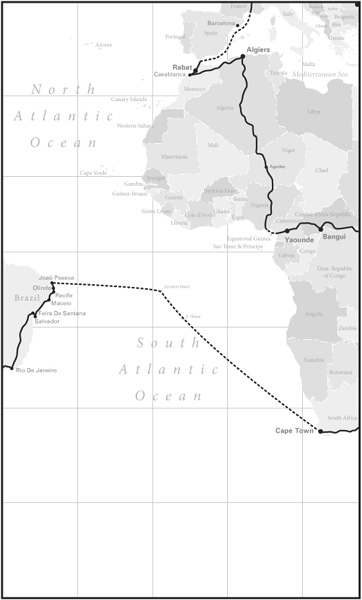

With both sails up and a two-knot current in our favour, we covered the remaining thirteen hundred miles to Brazil in nine days, a fast, rocky-rolly final leg that tested all our nerves. Mike got quite crabby with the kids: “Warren, clear this fishing tackle up right now.” “Tamsyn, for Pete’s sake, lay off that bloody piano.” Glenda failed to regain her sea legs. While she was cooking dinner one evening, a rogue wave sent her flying from the galley, across the saloon and head first into the instrument panel. She broke down in tears, told her husband she hated him and said she wanted to go home. Dinner was late that evening.

“¿Puede hablar más despacio, por favor?” While at the helm, I tried to learn Spanish. Can you speak more slowly, please? I had carried Spanish in Three Months and a pocket phrasebook the length of Africa in the lid of my rucksack, wrapped in a plastic bag. It was my first attempt at the language. I memorized lines from each book and repeated them aloud, trying to get the pronunciation correct. The “u” of puede sounded like a “w”; “s” was like blowing a raspberry. I would be a gringo, which made me think of A Fistful of Dollars.