I was tired of hitchhiking. Tired of sitting passively in metal capsules sealed from the world, blurred representations of it flying by outside the window. Tired of engines, their noise in my ears blanketing other sounds. I wanted to feel the breeze on my skin, go where I liked, stop where I liked, listen to bird calls and the wind in the trees, travel at my own pace propelled by my own legs. Yes, you meet people when hitching, but, to my surprise, I would meet more — many more — travelling by bicycle.

“Buddy comes in with half a ton o’ gunk round his rear axle and, get this, there’s a Sobeys grocery bag wound round the spokes, and buddy wonders why his bike ain’t running so smooth, so I goes to buddy, I goes, ‘Gotta take care o’ yer machine, y’know, cause it sure ain’t gonna take care of itself.’”

He had a moustache like a shoe brush, a pot belly, black hands holding a wrench or rag, a stay-awhile-let’s-shoot-the-breeze smile and always a biking anecdote or two to share with me. Jack worked with his brother, Paul, same big moustache, and his dad, no moustache but an eye patch, in the family shop.

Nauss Cycle Shop on Robie Street in Halifax was a charming mess. Front room with a line of bicycles and bicycle accessories crammed into it for customers to sort through (there was room for about one and his dog). Nauss Senior presided over this area. Beyond, twin garage-like back rooms clogged with wounded, half-made, repaired and half-repaired bikes with labels dangling from their handlebars. These next to workbenches barely visible under the brake cables and mudguards, the sprocket wheels and screws, tire irons, wrenches adjustable and non-, pliers, spokes and screwdrivers of differing sizes and lengths spread over them. Nails had been thumped into the walls and bike parts and tools of every description hung on them, waiting to be seized by an oily hand. This was Jack’s domain. In here, bicycles were created, revived, restored, adjusted, altered and made roadworthy. Sobeys bags were surgically removed from rear axles. Knowing next to nothing about bikes, I imagined that I’d need some kind of touring bicycle for what I wanted to do. Jack knew better.

“Yer gonna go off road with it, buddy?”

“Er, yup, guess so. Some of the time.”

“Well, you wanna a hybrid then.” Half racer, half mountain bike. Neither light and thin-tired like a racing bike nor heavy and fat-tired like a mountain bike. My Schwinn Crosscut had a sturdy frame that could probably take a fair load and medium-width, semi-knobbly tires to handle rough terrain. Believing that I would spend hours every day in the saddle, Jack put on drop handlebars instead of straight so that I could either pedal upright or crouch forward to take the weight off my bum. Twenty-one gears: three cog wheels between the pedals and seven on the rear axle. Gear-shifters sprouted from the ends of the handlebars. Handy, I thought; with many racing bikes, you had to reach down between your legs to change gears.

Jack also gave Schwinn self-healing inner tubes. Don’t leave home without them on a transcontinental cycle. I had not heard of them and had resigned myself to sitting on the side of the road countless times, cars whizzing past, with a wheel in pieces, searching for a pin hole with the help of a convenient puddle — perhaps the biggest drawback to travel by bike. But these heavier-than-ordinary tubes were filled with a kind of slime, a slime that would plug any puncture less than a couple of millimetres long right after it had occurred. There would be a little initial fart of air, but, providing the offending thorn or nail or whatever did not remain embedded, on you might pedal.

After a few spins round the block and some adjustments, it was time to put all the clobber on. Racks, panniers, pump, lights, odometer, mudguards and toe clips. Jack put a little repair kit together and hung it under the saddle and attached a triathlon handlebar extension. I bought myself a helmet, gloves, goggles and cycle pants with reinforced cushioning at the crotch. A security cable to lock the wheels. Not a water bottle. Since Africa I had carried a four-litre jerry can, and I would bungee this behind the saddle. Schwinn cost me $600, and the accessories a further $500. It was time for a test run.

On the coast, forty kilometres from Halifax, is Peggys Cove, called “Canada’s best known fishing village” by the guidebook in Halifax Youth Hostel. “A pretty place, with fishing boats, nets, lobster traps, docks and old pastel houses that all seem perfectly placed to please the eye . . . [with] a quintessential postcard quality about it.” Apparently, North America’s only official lighthouse post office was there, standing on smooth 415-million-year-old granite boulders known as “erratics” because they had been brought from a distance by a glacier. I might see a “pictorial in-the-rock” monument done by local artist Degarthe.

Peggys Cove was a hundred-kilometre loop out and back on Highway 333 from Halifax, a nice distance for a day trip at a leisurely pace in fine weather. It was now April, the morning clear and bright, temperature just above zero. I unpacked some of my rucksack into my panniers, bungee-corded my sleeping bag and jerry to the rack, dropped by on Jack for a gear adjustment, then pedalled off down the highway. An hour into the ride, the sun had gone, rubbed out by an oil-smeared rag of cloud. The temperature dipped. The wind picked up. Half an hour more and I was in driving hail that rapped on my helmet, bounced off the panniers.

I had gloves. I had goggles. All good training. Who knew what the rest of Canada would throw at me? Two and a half hours from Halifax, wiping goggles with soggy gloves, I strained for a glimpse of Canada’s maritime beauty spot. Dim shapes materialized: snow-coated sheds at the water, a dormant white and red lighthouse with snow stuck to the windward side, rounded snow-flecked boulders leading down to a whipped sea. No lobster traps, and not a soul in sight. I hit the brakes, eased my feet out of the toe clips and took stock. Old waterproof jacket now not so waterproof, fingers numb, ears numb, toes numb, side of face raw. I would have to think carefully about these problems. Cold and wet had gone right through me. I stayed for as long as it took to wolf a grocery-store sandwich and muffin, moistened by the snotty water dripping from my nose. I turned Schwinn around, steeled myself for the road home.

The first twenty minutes went well. The wind had let up. Hail turned to sleet, sleet to snow. Fluffy blobs sailing down nonchalantly splatted my goggles. I wiped, rewiped, veering this way and that as I did so. Fortunately, there was practically no traffic. Unlike the sleet, which had quickly turned to water on contact with the road, the snow stuck. Who would really want to go out to Peggys Cove on such a day except Peggys Covians? I slowed down, was having trouble making out the edge of the road. Another twenty minutes. Even slower. The road and the ditch were becoming one, hidden under a cotton sheet. Then there was no visible edge, and I lost the road entirely. The wheels bumped, telling me I was on rough ground. I steered in. It happened again. I corrected. A truck passed, sending up fans of watery slush in its wake. I followed in its tracks. The tracks disappeared. I looked for another vehicle, lost the road, hit a rock, swore and jerked the handlebars around sharply. And this overzealous correction took the wheels from under me.

I lay on my back, semi-dazed, looking up at feathery flakes floating down, licking away a ring of snow furring my lips. Then I had the good sense to roll off the highway into the ditch. Nice to have a helmet and gloves on. I was not hurt. I looked over at Schwinn. Nose down in the ditch, triathlon bar bent, back wheel spinning. Fine prologue to a seven-thousand-kilometre cycle. Was this a foolish idea, then? Like crossing the ocean in a glorified dinghy when I’d never sailed? I knew about as much about bikes as I had about yachts. Would this adventure yield as much pain as pleasure? There are easier ways, said the woman at Immigration. Was I just trying to pull a clever stunt?

A farmer in a Dodge Ram pickup saw me dusting myself down, pulled over and offered me a ride. He helped me lift Schwinn into the back. I tried to conduct a normal conversation as we headed cautiously back to town, but I wasn’t really inclined to chat. My fingers and toes didn’t care much for the sudden switch of temperature — an excruciating stinging sensation new to me. I was also pissed off at this failure to do a little test trip unaided. I vowed that I would not accept a lift on my crossing. Atlantic to Pacific all the way under my own steam. When the weather pounded me, I would stop and wait. When the bike broke, I would stop and fix it. A perverse decision, but it made me feel committed once more to my project.

“So, howjer test run go then, buddy? Was gonna mention a blizzard was comin’.”

Jack gave Schwinn a thorough check-up, found no damage. He removed the triathlon bar, gave me my money back. It was in the way of the map bag on the handlebars anyway. He asked me to write him a letter if I made it over the Rocky Mountains to Vancouver, let him know whether his baby went the distance. I left Halifax for Vancouver on April 11.

At Rogers Pass in the Rocky Mountains, with representatives from all ten provinces, John Diefenbaker, Prime Minister of Canada, declared the Trans-Canada Highway officially open in 1962. Linking Atlantic Ocean to Pacific, it had taken twenty years to build at a cost of a billion dollars. At 7,821 kilometres in length, it was the longest national highway in the world — although three thousand kilometres of it remained unpaved and the section through Newfoundland was still under construction. It was now 8,452 kilometres long, from St. John’s, the capital of Newfoundland, to Victoria, the capital of British Columbia. I joined it at Truro, a hundred and twelve kilometres north of Halifax.

With my bicycle fully loaded— four panniers (two on each wheel), handlebar bag, rack stacked high with tent, sleeping bag, sleeping mat and water — I felt for the first few days as if I was transporting weight-training equipment. One cheeky puff of wind and I’d topple over, be crushed and need saving again. I stayed in low gear, concentrated on balance, wondered whether the tires would pop, shooting slime everywhere, when we hit the first pothole. I learned quickly to distribute the weight evenly, get the heavy stuff like books, tins of sardines and jar of peanut butter near the ground. There had been one other cyclist at Halifax Youth Hostel, an Ontarian called Doug Nienhuis, who had similar aspirations. Doug had a racing bike that he found at the dump and a lot more stuff, including a computer, but Doug also had a trailer sporting a metre-long bendy aerial with a flag attached. His panniers were almost empty.

The Trans-Canada Highway would take me across Canada, but pedalling so far on one road would not acquaint me with the country. I was not on a racing bike aiming to set a record. In the manner of my journey so far, I wanted to wander and explore. Keep roughly westbound, thread back to the highway when I felt like making headway.

My first diversion was from Fredericton, after I had spent a week of steady pedalling on the Trans-Can. That week had taken me out of Nova Scotia and into New Brunswick; I had spent two nights in a shelter for down-and-outs called the House of Nazareth in Moncton, the rest under canvas with every stitch of clothing on, camping à la Tierra del Fuego. Fredericton surprised me. It is the capital city of the province and yet hardly larger than Sapcote, my home village. No big office blocks like Halifax, almost no traffic. Till I found Tourist Information, I wasn’t sure I’d arrived. One of Fredericton’s claims to fame is the Coleman Frog, caught in a nearby lake in 1886. I went to see it at the York-Sunbury Museum on Queen Street. On the display case a card said: “When Mr. Coleman first found his pet it was like any other normal frog, but on a diet of whisky and June bugs, cornmeal and porridge, it eventually grew to 42 lbs.” It was the size of a bulldog and squatted like one, waiting for a table scrap. It had a mud-brown back and legs, a yellow stomach and a broad grin of well-fed contentment. I wanted to prod it with my finger. The thing in the case looked suspiciously like something made of papier mâché.

“If you miss Cape Breton Island (the northern end of Nova Scotia), don’t miss the Gaspé,” someone said to me in Halifax Youth Hostel. From Fredericton, I struck north on Highways 8 and 11 to the province of Quebec, then joined 132 going round the Gaspé Peninsula, the lower jaw of the St. Lawrence River mouth. I was the only cyclist on the road. Waist-high banks of snow to either side bled over the empty highway. I passed hibernating villages that reminded me of Peggys Cove, dwarf lighthouses, a pale brown, sheer-sided sandstone warehouse offshore called Roche Percé, ringed in ice, with a horseshoe hole punched in one end. At the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula, called Cap aux Os because whale bones used to wash ashore there, miniature icebergs idled in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, bold against the blue water in bright spring sunshine. Some of the bergs were as large as Shandita.

“Y fait pas chaud pour faire du camping, là!” a maternal waitress exclaimed in Anse-aux-Gascons when I asked her if there was a snow-free spot near her diner to stick up my tent for a night. Bit fresh for camping, innit! It was one of the few utterances I understood. After French Africa, I thought my French would be in good shape for Quebec. But the accent fooled me, distorting words, making them run into one another. Many statements seemed to end with a little “luh” sound. When I heard it, I took it as a cue to nod vigorously. Her work done, the waitress invited me to climb back on my bike and follow behind her car.

At her house, she seemed uneasy. Her husband was away. He wouldn’t approve of her bringing back a strange man. She quickly installed me in a back room, said “bon nuit.” I thanked her, said she was “très gentille,” tried to indicate that I was utterly harmless. In the morning, judging by the breakfast spread, she had been up long before me. Ham, eggs, potatoes, three types of cheese, three types of jam, cretons (pork pâté), a rack of toast, pineapple juice and coffee. I thanked her profusely, saying she had given me “vigueur pour la route.” I wondered as I left whether she would tell her husband.

I burned the fuel rapidly. Rounding the peninsula and heading down the St. Lawrence for Quebec City and Montreal, I battled a headwind that gradually refrigerated my body, leaving me with creaky knees, a cardboard nose and a stick in my neck by the end of the day. My hands gripped the handlebars like talons. I had to massage them under a warm tap for ten minutes before they would clasp a soup spoon. When would Canada warm up? Would Canada warm up? No wonder ninety per cent of the bloody population lives huddled along the U.S. border. I was now cycling wearing two pairs of gloves, two pairs of socks and a headband covering my ears under my helmet. Big hot meals were essential. My appetite raged. The Québécois gave me thick pea soup and poutine: a heap of fries and cheese curds smothered in gravy. Filling, but I could not eat enough. Not till I met the Hovingtons.

Paulette, Lucie and André Hovington lived with their partners at intervals along the St. Lawrence. I stumbled into the husband of the first in a tiny village called Baie-des-Sables. Marcel LeClerc, a lean man in his early sixties wearing a baseball cap, was looking ruminatively at the river, arms behind his back, letting his breakfast settle as I was packing away my tent after another frigid night.

“Qu-est ce que vous regardez?” I inquired. And it all began right there.

“Pas un journée pour faire du bicycle en short, là,” he said, looking at my bare knees. I should come in and drink some of his grandson’s homemade beer. Inside, I met his wife, who spoke English. A bilingual getting-to-know-you followed. Canadian roadmap out, Times World Map out. Then it was lunchtime. After an afternoon of getting-to-know-Baie-des-Sables (almost possible from the doorstep: fifty houses and a church), my schedule went: hot shower, more homemade beer, pasta dinner that included neighbour Phillippe, ice cream topped with maple syrup for dessert (a Canadian delicacy, had I tried it?) and the grandson’s room for the night. Paulette had a nice relationship with the neighbour. He hit his golf balls into the St. Lawrence, she retrieved them at low tide.

Marcel and Paulette were retirees living in a clapboard house hospitably decorated with potted plants, floral toilet paper, seashells, revolving spice rack in the kitchen, embroidered sofa cushions in the living room. They had a bedroom upstairs set aside for Maxime. In there, on the walls, I found Hieronymus Bosch’s depiction of hell (bodies being tortured and mutilated) beside a poster of the heavy metal rock band Iron Maiden’s “Beast” (a mad-faced zombie). Moving along the wall, “Commander of Darkness” (a skull with eyeballs) was set above a row of skeletons, then a toad with talons devouring a naked woman, then something called “Festival of Death,” featuring Cryptopussy, Suffocation, Gorelust and Neurotic Mutation. All the words in dripping spidery lettering. I lay in the grandson’s bed and tried to conjure up a picture of him. His surname, Tremblay, seemed to suit the bedroom.

Before I cycled off in the morning, belly loaded with ham, scrambled eggs, cheese, toast spread with cretons, toast spread with raspberry confiture, toast spread with caramel, croissants spread with all three, fruit juice and coffee, Paulette did my laundry and gave me the addresses and phone numbers of her brother, André, in Donnacona, and her sister, Lucie, in Cap-de-la-Madeleine.

Three days later, I was Hovingtonned again by André and his wife Pierrette. When Schwinn and I pulled in at Quebec City Yacht Club, the small bearded man drilling a hole in his yacht Jeanie was not surprised. His sister had called. André Hovington was a member of the Coast Guard working for Marine Search and Rescue.

“I ’ave a littul surprise for you,” he admitted after we’d inspected an icebreaker undergoing repairs. I was invited to put on a pair of earphones. Two hundred metres up in a red two-seater rescue helicopter, I could appreciate the cluster of antique buildings that make up the heart of Quebec City. I could see the Citadel, a star-shaped fortification that the French started building in 1750 to store gunpowder. The British completed it, having defeated the French and taken control of Canada, the following century. I could admire the steep green roofs and multiple turrets of the elegant Château Frontenac hotel. And, because we landed exactly in the spot we’d taken off from, I didn’t feel that I had broken my round-the-world-without-aircraft rule.

We picked up Pierrette from work, and the plan was: take Tony home, look at his maps (André hoped to sail around the world), give him several beers, a large dinner and a bed for the night. Next day, get his bike repaired (a broken spoke in the rear wheel), wash his clothes, feed him again (full Quebec breakfast), take him to the grocery store and buy him the food he needs for his journey, give him a Canadian flag badge to pin to his chest, a plastic snowman to hang from his handlebars and a cord to attach to his goggles to save them from crashing to the deck should they get, well, jolted from his nose when he unwittingly hit a pothole. I was bowled over. Didn’t know what to say. Merci beaucoup? I said it several times till it seemed emptied of meaning. André’s parting words were, “Lucie’s expecting you for tea.”

So off I went, Canadian flag on tit, plastic snowman dangling, my destiny not my own. I was in the hands of the Hovingtons. Cap-de-la-Madeleine is ninety-six kilometres from Donnacona. I was humming to myself about halfway to my destination when I heard a shout from an isolated bus shelter at the side of the road: Doug Nienhuis from Halifax Youth Hostel. Chapped lips, bags under his eyes. He had stuck with the Trans-Canada through New Brunswick. No snow, but rainy days and nights.

“My tent is a deluxe model. Comes with built-in shower,” he said miserably. “And fuckin’ dogs chase my flag.” The man was in need of a Hovingtonning.

Two hours later, we turned down a tree-lined drive, extensive lawns to either side. At the end, Lucie Hovington, with short white-blond hair and the kindly face of her sister, and her husband, bald and smiling, the shape of an accomplished businessman. I began making lots of funny French noises in an attempt to convey the message, “Sorry to intrude. Even sorrier to intrude with another intruder,” but Hovington hospitality brushed aside such excusez-moi’s.

Accustomed to instant noodles warmed up on a camping stove, Doug gawped. “Tea” was soup and hot roll, homemade tourtière (meat pie) with mashed potato, turnip and broccoli, seen down with red and white wine, blueberry pie and cream, cheese and biscuits to follow, coffee and cognac. Then it was time for swimming, or rather bobbing. Hovington III had an indoor pool. Horribly swollen after second helpings of pie, we eased ourselves in and floated on foam lily pads, grinning like Coleman frogs.

The next day, I thought we’d be on the road to Montreal, only a hundred and forty-four kilometres away, but no, we were powerless Hovingtonites. Lucie cleaned Doug’s clothes and shoes in the smallest of pauses between Big Breakfast and Large Lunch, which might’ve run into Tremendous Tea revisited had there not been the suggestion of a stroll. The evening meal reintroduced the Donnacona Hovingtons, André and Pierrette, and I was told of a fourth Hovington in Laval, a suburb of Montreal. It was all too much. Any more and I would need a trailer like Doug’s for my stomach. It surprised me that none of the Hovingtons seemed to be overweight. After a long breakfast the third day, Lucie pressed zip-closing plastic bags bulging with cheese, grapes, salty crackers and chocolate chip cookies into our hands.

I had not known hospitality like it. Couldn’t imagine it happening back home. These people didn’t know me from Adam, yet I was received like a wayward son who had been gone for years and had finally drifted back, basically unharmed but desperately thin. I had stories they wanted to hear. None said it, but maybe Doug and I were doing something they had always dreamed of doing: bungee a few bits of gear to a bike rack and cut loose. They gave me a name. I was “Le cycliste fou.” The mad cyclist, the intriguing oddity they seldom met. Their kindness encouraged me. I hadn’t known anyone in Canada, but now I felt that I had friends and that there would be a string of helping hands stretching along the Trans-Canada. During my crossing, I would spend forty-three nights under someone’s roof or camping in someone’s yard. I would exchange letters with the Hovingtons for more than ten years.

Doug had friends in Montreal for us to stay with, two girls our age who lived in a small apartment on Rue de la Visitation, a kilometre from the city centre. One of them, Nadya Ladouceur, I took a particular shine to. She was twenty-five, had short brown hair and brown eyes, wore no makeup, had a collection of bruises on her arms from volleyball training and was bilingual. Nadya took me to her favourite street café on Rue St. Denis for chocolate-filled croissants and espresso and went jogging with me in Parc la Fontaine at the top of her street. She warned me that if I came to Parc la Fontaine on my own and did my stretches in shorts, I’d be accosted by gays, Montreal being home to one of the largest gay communities in Canada. Nadya and I spent three nights together.

May. Alone, I pedalled on. Ottawa, Pembroke, Sudbury. The weather had warmed up. Under-gloves no longer required. I got into a steady rhythm. Days of a hundred and ten, hundred and twenty, hundred and forty kilometres, beginning late morning after an enormous greasy breakfast at a truck stop, lunch at some remote spot away from the cars, watching birds and flicking off the insects that had stuck to me. Highway-side restaurant or someone’s home for dinner. I put my tent up for the night wherever a patch of grass suggested itself. A version of the English blackbird with handsome red and yellow epaulettes and a cousin of the English coal tit called the chickadee kept me company.

Schwinn performed well. I cleaned and oiled her daily, kept the tires pumped up hard. If there were punctures, I didn’t know about them. The worst damage was to the spokes. I snapped seven in all, always in the back wheel. In Quebec and Ontario, the Trans-Canada Highway was especially cracked — at times with deep, fist-width fissures every six or seven metres for hundreds of kilometres. It was hard to be patient and not take these at speed, punishing the back wheel. Each time a spoke went, the rim warped, and I had to get off, unhook the brakes and pump the bike along like a scooter to the nearest gas station. Jack’s repair kit contained a spoke wrench, and I learned how to thread new spokes and get the wheel to spin true using a vise.

June. Great Lakes, Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay, Kenora, Winnipeg.

June 5, 1995

I pick the fly off my arm and inspect it. Quite the loveliest I have seen. I hold it by the legs close to my nose, turning it slowly. Orange body with brown ribs, wings semi-transparent with brown wedges decorating the leading edges, fabulous pair of iridescent green eyes speckled with dots and a black drill-bit mouth-part painted orange where it joins the head. Deer fly. Shame to kill it. But it was him or me. Bright squidge of orange blood. Speed of 24 kph not good enough to shake him off.

At rest, I am easy meat. I have met the Canadian deer fly, horsefly and mosquito, but worst is the blackfly. Attacks in clouds, crawls up the nostrils, in the ears, bites the scalp, somehow gets down my cycle pants, leaving bloodspots hard not to scratch. Not a distant cousin of the English blackfly that sits dopily on rosebushes and drinks sap.

I crossed Canada’s official midway line, a sign just east of Winnipeg, on June 20, with 4,665 kilometres on the odometer. At Winnipeg Youth Hostel, I talked road surfaces with two Trans-Can cyclists coming the other way. This pair was smarter than me, crossing the country with the prevailing wind and the general tilt of the continent.

“So what’s the 17 like between here and Thunder Bay?”

“Two-way traffic, load of cracks, real ball-buster, logging trucks shave your whiskers,” I offered. “How about Number 1 to Regina?”

“Prairies, divided road most of the way, good shoulder, all flat, hundred and fifty kilometres a day no sweat. Dull shit. Get a Walkman. And it isn’t Re-jean-a, man. Rhymes with a part of the woman’s anatomy, eh?”

A Trans-Can cyclist on the road is pretty easy to spot. Criss-crossing frayed bungee cords pinning spare clothing to the rack, multiple water bottles, buggy T-shirt, ruddy face with trance-like expression, maybe a flag saying “St. John’s or Bust.” I met six in all, four heading east, one west. A couple of years earlier and I might have looked up to see a rick-shaw and a bearded, shaggy-haired Canadian coming towards me. Rickshaw imported from Pakistan with one gear, bells and coloured tassels, canvas hood over empty passenger seat, pennants fluttering from aerials. Pushing up the hills, it took Bernie “the Bike Man” Howgate a hundred and sixty-seven days to pedal from Victoria to St. John’s. With diversions, Schwinn and I would probably cover the same distance but, with twenty-one gears, in about half the time.

I did a hundred and sixty kilometres from Alexander, Manitoba, to Whitewood, Saskatchewan, a hundred and seventy-six the next day to Regina, then a hundred and fifty-two through Moose Jaw to Chaplin, and a hundred and seventy to Tomkins. Out of Saskatchewan, into Alberta. I wasn’t bored. After the choppy, exhausting Canadian Shield lining the Great Lakes, it was a thrill to race across flat expanse, a green sea of crops to either side, waiting for the next grain elevator to materialize on the horizon like an island. Days were alike. My mind drifted. I thought of home, my parents sitting in their garden reading the Sunday Times, cat lounging on my father’s lap. I thought about the Pacific Ocean. Visualized myself setting out across it on the deck of a big ship. No sailing and a wretched stomach this time. Vancouver was a big port. Maybe I could catch a ride on a cargo ship to Asia.

Indulging a boyhood interest in oversized lizards, my diversion off the Trans-Can in Alberta was to Dinosaur Provincial Park, two hundred and forty kilometres east of Calgary. The park was more interesting to me than the dinosaurs. I dropped into a parched valley of sandstone and mudstone hoodoos named “les mauvaises terres” by early French-Canadian trappers traversing the region — “badlands” because they could find no water and few furred animals to catch and skin. The bleached, deeply fissured sandy ridges looked as though they’d been pinched and squeezed dry by a giant. Numerous seventy-five-million-year-old duck-billed bipeds have been dug out of the valley and shipped from this field station to the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, a hundred and thirty kilometres or so northwest. There were one or two skeletons of hooded, horned quadrupeds like small triceratops inside the station; outside, a full-size Tyrannosaurus Rex with ridiculous hydraulic gnashing teeth.

The westbound Trans-Can cyclist is happy to see Calgary. Calgary means an end to the flatlands he thought would never end. Then, through his tinted goggles, he sees the storm front beyond. The grand-daddy of storms, hugging the ground and stretching right across the horizon. He stops twenty-five kilometres from the city and removes his goggles to get a better look. Can he pedal fast enough to reach the city before it pounds him? His eyes adjust. The great dark mass ahead has not moved. Not a storm. The Rockies.

My ball-hugging cycle pants were popular in Calgary. It was Stampede week, and lots of Clint Eastwood look-alikes in fringed jackets, cowboy boots and Stetsons strutted around with their thumbs in their belt loops. After the seventh wolf whistle, I went back to the hostel and changed. I paid eight bucks to get into Stampede Park, then, after watching a rope-making demonstration and piglets in numbered bibs race around a dirt track, another eight bucks to enter the stadium. Cowboys on horseback clutching milk bottles tried to lasso longhorn cows and extract a centimetre or two of milk. I saw calf-roping, bareback riding, saddle-bronc riding and, most exciting of all, bull riding. The bulls, brawny and incensed, had names like Hot Toddy and Fear No Evil. They tossed cow-boys into the air and then tried to drive their horns into them. It was the job of nimble, plucky men called rodeo clowns, with provocative red ribbons pinned to their shirts, to divert the bull’s attention.

I steeled myself for a hard ride of my own over the mountains, but I was on the road for a week out of Calgary before having to take a serious incline. The Trans-Can simply snaked around the feet of the snow-hooded giants to left and to right, almost mocking their unscalable walls. Magnificent wrinkled faces grinned down at me. Surely this couldn’t last.

At Banff, a hundred and twenty-eight kilometres west of Calgary, I got off the saddle and went for a climb. Up Tunnel Mountain (1,692 metres); up Sulphur Mountain (2,285 metres). Looked down the Bow River Valley at pine woods following the river bends, at pale, phallic sandstone hoodoos sprouting from ridges and at the towering mountains of gnarled rock hemming the valley, their crenellated crowns spotted with snow. As in Parque Nacional Lauca in northern Chile, the definition of the shapes, the boldness of the colours was extraordinary. It was as if the Rockies, like the Andes, knew no air pollution. Then on to Lake Louise, fifty-eight kilometres northwest of Banff. Instead of the Trans-Can, I took the Bow Valley Parkway, a leisurely, undulating parallel route. The Rocky Mountains were going to be a breeze; men had found a way to run the highway through the bottoms of the valleys. From above, glacial Lake Louise was a spilt lime milkshake.

“Welcome to fifty kilometres of cycling from hell!” It wasn’t till I was beginning my day on a hill out of Donald, British Columbia, two hundred and ninety kilometres west of Calgary, that three cyclists overtaking me on racers indicated that the easy days were over. Fifty? My bike wobbled. If it’s fifty, then it must be a gradual incline, I reasoned. So gradual, in fact, that it really won’t trouble me. After all, this is the Trans-Canada Highway, and it can’t be too steep because trucks and cars need to get across the mountains to Vancouver.

Thirty-two kilometres of ups and downs were followed by a fierce, unremitting ascent of eighteen. Trucks shuddered past me blowing smoke, cars banked up behind them. I hunched down and concentrated on the five metres immediately ahead of me, then the next five, then the next. My clothes filled with sweat. Sweat dripped off my nose, leaked from my wrists over my gear-shifts, streaked my legs. I laid a spare T-shirt on the handlebars to wipe away the curtain that kept descending from my helmet into my eyes. Every fifteen minutes, I took a slug of water from my jerry. Lowest of my gears all the way. I stubbornly refused to get off. The worst of the torture was suffered in semi-darkness as the road passed through the snow sheds protecting it from avalanches. These buggers almost finished me as I strained to see the road edge and struggled to breathe air made foul by bottled-up exhaust fumes. I was a gasping, writhing, bellowing animal.

Mid-afternoon, the last shed was behind me. The gradient eased. I could see a building. A sign was coming up on my left: “Rogers Pass — summit 1,330m.” Beyond, a busy car park and gas station. I pulled in and practically fell off the bike, unable to get my feet out of the toe clips. I was dizzy, there were black spots in front of my eyes. My legs were twitching. I stood still for a moment, breathed deeply, then wobbled through the gas pumps and leaned Schwinn against the side of a convenience store. Ripping away my helmet, I went into the bathroom and shoved my head under the taps, blew out my nostrils. Refilled my jerry can, drank and belched. I had taken five hours to get here from Donald. The hardest fifty kilometres I had ever pedalled.

There was no rewarding view to behold. Trees lined the highway on both sides. Around me were cars, trucks and camper vehicles disgorging people looking for gas and snacks. After fifteen minutes of taking slugs from my jerry can and staring, I wandered stiffly into the store. Three bucks for a pita-bread envelope with a smear of something dark brown inside. I slumped on a bench and dug around in one of my panniers for a can of sardines to tip into it. I treated myself to a muffin and a cup of tea. I loaded the tea with sugar, sat stirring it slowly, legs spread uselessly in front of me, eyes glazed, happy. Under my own steam, I had made it up the Rockies.

A week and a half later, I was in Vancouver. It wasn’t all downhill from Rogers Pass. There were two further mountain passes through the Cascade and Coast ranges, but neither was as punishing to reach. My diversion off the Trans-Can in British Columbia was at a little town called Sicamous. Seeing a slender blue worm on my map, I took Highway 97 south and cycled down the side of Okanagan Lake for two days. In this famous fruit-growing valley, stalls at the roadside sell peaches, apricots, plums, cherries and apples. Bags of fruit swinging from my handlebars, I kept an eye out for Ogopogo, B.C.’s Loch Ness Monster. I rejoined the Trans-Can at Hope.

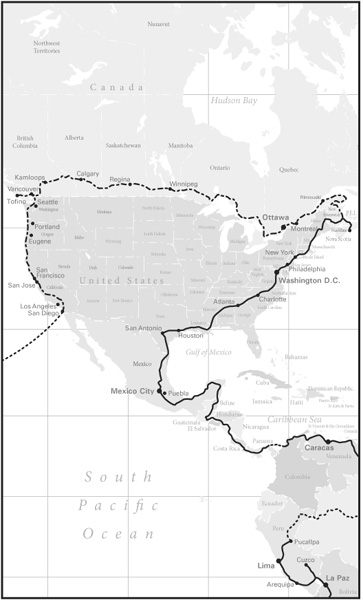

It took me three and a half months to cross Canada on a bicycle, Atlantic to Pacific, 7,304 kilometres including diversions. Sixty-five days in the saddle, forty-six off. I rolled into Vancouver on July 30 and looked up Bob Hornal, my friend from the Amazon. I stayed with him for six weeks. I phoned Dave Lewis in Raleigh. He wanted to know if I’d grown a pair of “monster thighs.” I wrote a letter beginning “Dear Jack, Schwinn and I made it” and sent it to Halifax.

“But you haven’t made it to the end of the Trans-Can,” Bob said swinging from side to side in the hammock he’d had on Shandita, strung up now across his apartment.

“Victoria?”

“Tofino.” According to my map, the national highway ended at the B.C capital on Vancouver Island. Taking a break from my search for a freighter to cross the Pacific, I went by ferry to the island, cycled up and over to its west coast and discovered a sign next to the water. “Pacific Terminus Trans-Canada Highway.” A woman walking her dog took a photograph of me with Schwinn’s wheels in the sea. I thought about cycling into the water, saying farewell to Schwinn, swimming back to the beach and hitching to Vancouver, the cycling phase of my journey done.

It was just as well that I didn’t ditch the bike.