Deepest of all oceans, the Pacific covers half of the Earth’s water surface and is equal to a third of the entire surface of the planet. It is twice as large as the Atlantic being 11,000 miles wide at the Equator. It has no northern or southern boundaries and comprises an area of 63 million square miles.

— Historic and Geographic Tourist Map of Saipan

Name: Tebrinda | Water: 75 gallons |

February 27, 1996

Day 21. Dumpf. Dumpf. dead in the water. Three-metre swells lift the hull and drop it unceremoniously. Dumpf, goes the stern, slamming the surface. The wind is down, the sky overcast and threatening. We should be in Hilo, hawaii, according to the Float Plan. Instead, we are 800 miles east of it, incapable of going anywhere. I am in the companionway, the only one awake, eyes locked on the horizon. Waves of nausea come and go. Nothing left in the stomach. I force down pretzels and take a gulp of water.

There is a line deployed to starboard. On the end, a drogue like a huge jellyfish. We are trying not to drift back the way we came. Hold position till we can muster the energy to get ourselves out of this fix.

Below, Larry is flat out on his back on the cabin sole. Dented grapefruit roll around, smacking his head. They don’t seem to bother him. He wears yellow oilskins and gumboots. His white hair is matted and gummed to his scalp. White bristles cover his chin. He has thrown in the towel after the hard days and nights, by last night’s destruction, by the awkward business of deploying the sea anchor. Far cry from the tall, immaculate, well groomed skipper who invited me to join him on a “cruise” to Hawaii in October.

Commercial freighters cross the Pacific Ocean from Vancouver to Asia all the time, floating warehouses a kilometre long, standing fifty metres out of the water, with vast bridge superstructures and pillar funnels, company names plastered down their sides: Sinotrans, Hapag-Lloyd, Saga, Norasia. Cargo holds full of lumber, minerals, oil, steel, or decks stacked high with metal containers. The voyage to China or Japan takes twelve to fourteen days.

Vancouver is the largest port on the Pacific coast handling foreign tonnage. Docking terminals at Centerm and Vanterm in Burrard Inlet, Lynnterm north of the city, Roberts Bank forty kilometres south. From Bob Hornal’s apartment, Schwinn and I visited them all repeatedly during August and September. I was darned if I’d sail across an ocean twice the width of the Atlantic. It would take bloody ages.

In 1995, anyone could wander onto the commercial docks, chat with the stevedores, run up a gangplank and ask to speak to the captain. I asked, I begged to be taken on as a crew hand. I promised to work like a dog and live in the bilges. I lied about my seamanship, I lied about my sick mother stranded in Vietnam, I offered bribes. No. Against company policy. No. Sorry, no longer done. Now, if you don’t mind, I’m busy. I considered sneaking aboard a freighter at night with a sack full of groceries on my back, passport in a Ziploc bag. Try and last the fortnight in a lifeboat. But I couldn’t whip up the courage to do it. Stow away on the wrong boat and I might be made to walk the plank a thousand miles from land.

With three days left till my half-year visa in Canada was up, I invited myself aboard the Hoegh Musketeer, a new arrival at Lynnterm, and presented my case to Captain Oddbjørn Tharaldsen, a straw-haired man with an eroded face. Going round the earth, aircraft against my religion, funds dwindling, need to make it to the next land mass. Oddbjørn and I hit it off right away, probably because he was drunk and fancied having a chat about the sea and Asia. Promising to make inquiries, he told me to drop by again when he was sober.

“Ah, ze Englischmann. Kom. Ve vill make ze Telex,” Oddbjørn said the following morning. “You must be humble if you verk as crewman here. Ve vill treat you just like oza crew, ya?” I nodded, but I knew the decision to take me on was with the ship’s owners in Norway. I’d run into a few captains who remembered the good old days when “workaways” were allowed, when unknowns could toss their kit bags aboard and swab decks for a passage. Mediterranean Cargo Service in Durban had already told me that things had changed. Men in offices half a world away, who weren’t travellers or romantically nostalgic, wouldn’t break rules.

“If it just me, I say no problem. You kom to Japan wif me,” said Oddbjørn, sounding as disheartened as I felt when the Telex came through.

“How does four hundred bucks sound? Little secret between you and me?”

“I vud loose my job.”

“Crate of whisky?”

I bellowed at the ships I saw calmly humming out of harbour, kicked myself for spending so long in Vancouver. There’s persistence and then there’s flogging a dead horse. Blame it on my star sign: stubborn Taurus. The yellow line I’d drawn on my world map, my imagined path round the world, went up to Alaska from western Canada, my idea having been to narrow the expanse of water to cross to Asia. Forget Alaska. It was mid-September. By the time I cycled up there, the first snowflakes would be falling. With the onset of winter, the shipping scene could be as lively as it had been in Ushuaia at the other end of the continent. There was only one way to go now.

I had a single lead: Harvey Reynolds. Curious about the yacht scene in Vancouver, I wandered into a sailors’ bar called Stamp’s Landing one evening and struck up a conversation with the man on the next bar stool. Harvey was an easy-going, bushy-bearded Rhodesian bound for New Zealand on Wet Dream, a fourteen-metre sloop. The next leg of his trip was Vancouver to San Diego. He planned to join the “Baja Ha-Ha” at the end of October, an annual exodus of yachts from San Diego to Baja California, Mexico. Yachties liked to over-winter in Mexico, then cross the Pacific in the spring. Harvey already had crew for the leg to California. Maybe I’d care to join him in San Diego? I didn’t want to head south and cool my heels for half a year in Mexico, and I didn’t want to sail to New Zealand, but San Diego sounded like a good place to search for a boat.

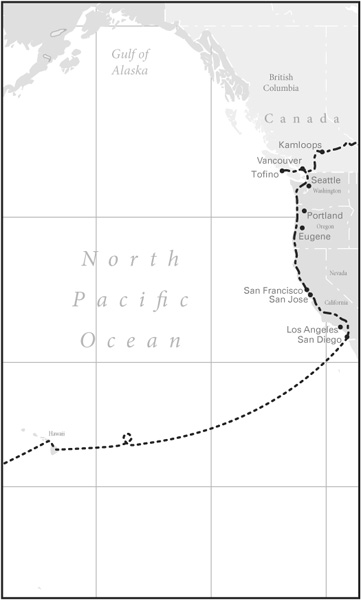

It took a month for Schwinn and me to do another 3,150 kilometres. We followed the Pacific Coast Highway most of the way: Washington, Oregon, California. Cutting inland through the Mojave Desert just south of Big Sur to go around Los Angeles, desert seeming preferable to urban jungle for a pannier-laden bike. The slime-filled inner tube on the rear wheel finally conceded defeat one afternoon outside Bakersfield when an explosion sent phlegm in all directions. Fortunately, it didn’t happen at a bus stop. No nail or broken bottle was responsible, only heat and the slow weakening of the skin by the hundred pinhole-sized, slime-plugged punctures collected since Halifax. I hitched back into town to replace it. As I pedalled south, I talked myself round to the idea of sailing west. I thought back to my Atlantic crossing with the Smiths on Milkwood. Bit of a rough start, but once I’d found my sea legs, a valuable experience. Maybe in San Diego I would be able to find something bigger and more stable. Captained by a sailor, not a hairdresser. Without kids.

Protected from the ocean by two fingers of land, one jutting down from the north, one sticking up from the south, San Diego Bay is one of the Pacific coast’s best natural harbours. Twenty-two and a half kilometres long and dredged to create forty square kilometres of navigable waters, the bay is home to a score of marinas. I aimed at what I thought might be the centre of things: several marinas tucked behind Shelter Island, a T-shaped spit of land made with the spoil from dredging. I found Wet Dream at Kona Kai Marina.

Harvey didn’t mind me living on board till the send-off party for the Ha-Ha, providing that I fed myself. Then, if I didn’t find anyone heading west, I could go south with him and the flotilla. The last day of October saw a crowd of people around a pair of barbecue grills, hugging one another, eating hotdogs from paper plates and trying to get drunk on Budweiser and Coors. A skipper’s wife had made chocolate cake. A brisk autumn wind off the sea blew people’s caps off. Half a dozen boatless vagrants like myself threaded through the crowd with “Crew Available” badges pinned to our breasts. Mine had the additional word “Hawaii” on it. I circulated for almost two hours, wearing my most optimistic smile and trying to be charming, then sat down on a bench defeated. The whole damn lot of them were off to Mexico.

“Saipan.”

I was scowling at the Pacific Ocean while seeing off my seventh hotdog (my cycling appetite still with me) when a hawk-nosed man with white hair and moustache addressed me. He was holding an orange juice and looking down at my badge. He wore a navy blue T-shirt marked “Downwind Marine” and beige shorts.

“Got me there,” I replied. “Polynesia?”

“Marianas. Island near Guam.” Evidently I was still frowning. “’Bout a thousand miles south of Japan.”

Larry Roberts was a real estate agent from Arizona, living now in San Diego, with an interest in sailing but no boat of his own. He was listed in Latitude 38 and Santana, local yachting magazines, as a delivery skipper. He sat down and told me about Tebrinda, the recent purchase of a U.S. government official by the name of Hans Hoogeveen, who lived on Saipan. Hans bought Tebrinda in L.A. and had tried, earlier in the year, to sail it home single-handed. He was blown back to California by storms. Hans had found Larry, asked him to deliver the boat to Saipan as soon as possible and flown home. Tebrinda was still in L.A.

“Josh, a friend of mine, is gonna help me get it down to San Diego next week. Looking for someone to join us for the crossing from here. First leg to Hawaii.”

We talked a bit about my Atlantic crossing, about the yachting scene in South Africa. Larry told me to call him in two weeks if I was interested.

I walked slowly back to Kona Kai. No. Not a good idea. Don’t call him. Tebrinda was no bigger than Milkwood, a fact that made my stomach squirm. And Tebrinda had just taken a beating in storms. Was she damaged? Was the boom still firmly attached to the mast? Did the autopilot work? This boat would need a careful inspection before departure. No. Come to your senses. There was good reason, no doubt, why all these other yachts were going down to Mexico to wait out the winter. I watched a plane flying west high in the clear sky, white contrail stretched behind. But then, Larry was a delivery skipper. He must be a competent, experienced sailor, mustn’t he? I asked Harvey.

“All kinds of wazzocks out there these days. Never trust a man with a moustache.”

“But you have a moustache, Harvey.”

“That’s different. Mine’s attached to a beard.”

There was one compelling reason to sail with Tebrinda. The owner was covering all expenses. I hadn’t lied to Oddbjørn. Funds were low. I had just under a thousand bucks left. I had to make it to Japan quickly and work there teaching English for a while to build up the exchequer. I got out my world map. Saipan, hey? Seven thousand miles or so west. Four-fifths of the way across the Pacific.

Wet Dream left for Mexico without me. I lodged myself at Point Loma Youth Hostel. Larry aimed to set sail for Hawaii early in December. I found a job with the Hare Krishnas selling environmental T-shirts to tourists at Embarcadero and Seaport Village and in front of the San Diego Zoo. “Save the Whale,” “Protect Rainforests,” that kind of thing. Tebrinda arrived at Shelter Island in mid-December.

“Leave for Hawaii after Christmas,” Larry said. I met the other crew hand, Josh Wilson, another Arizonan with a moustache. We went to see the boat. Definitely reminiscent of Milkwood, but with an extra mast and sail at the stern. Hopefully, this would make it go faster. Green trim on the sails rather than Milkwood’s burgundy, I noticed, and a matching green stripe along the hull.

“End of January,” said Larry when I phoned him on Boxing Day. “Work commitments. Gotta do some repairs on the boat, too. And provision it. Early February at the latest.”

Rain stopped the shirt-selling in San Diego, so I shifted with the Hares to Las Vegas. To my surprise, “Save the Whale” shirts sold there too, provided that the whale had “Las Vegas” printed under it. I manned one of four tables on the sidewalk outside a casino soon to open called New York, New York. Things went fine till goons driving by in cars with blackened windows began dumping buckets of food slops and body waste on our shirts. One evening, I went home coated head to foot in white powder from a fire extinguisher. Hare Krishnas were not welcome in front of casinos — even ones not yet up and running.

When I arrived back in San Diego, Larry seemed finally to be organized. He had a Float Plan for the first leg, with a copy for Josh and myself, and a list of stores.

“We have long-grain basmati rice, Dinty Moore canned stews and cans of Steak Ranchero Chili. Finest red-skinned potatoes. We have coffee and coffee creamer with hazelnut. We have tea, regular and herb — cinnamon and apple, peppermint and ginseng. Top quality honey-coated granola and brown unwashed free-range eggs for breakfast. Box of oranges, another of grapefruit, third of bananas.” My mouth was watering. With this degree of attention to matters of the stomach, surely the rig had to be okay. I was also pleased to learn that we would not be alone. There was one other boat willing to brave the winter sea, a thirteen-metre Morgan sloop called Bravura. Larry had recently made friends with the captain, George DeBarcza. We would “buddy boat” to Hawaii.

“Are you ready for a cruise to Saipan then, Tony?” I looked at Larry. His hair was combed, his moustache clipped; his eyes gleamed. He exuded confidence. A mammoth voyage was about to begin — whether I stayed with Tebrinda all the way to Saipan or not. No doubt this little ketch would knock me about, but I had been on the American continent long enough. It was time to cross the world’s deepest, widest ocean. I felt a familiar shiver of anticipation.

On February 5, the night before we left land, I went to see a film with Josh called White Squall about high-school kids taken to sea on an old-style square-rigger for a character-building experience. Towards the end of the film, the ship is caught in a violent storm. The kids are unable to climb the rigging to change sail because of the danger of being struck by lightning. A huge wave broadsides the ship and it capsizes. Several of the crew are trapped inside as it sinks.

With a lump in my throat, I gave Schwinn to Marjorie, a Scottish woman I used to teach with in Japan, now living in Chula Vista. She offered to sell the bike and send me the money.

“You’ll have to pay someone to take her,” I said. The back wheel was buckled, the back tire bald, the brake pads worn to the metal. Most of the low gears didn’t work and the chain skipped on the cogs. One of the pedals was split, there was a rip in the side of the saddle, the odometer had had it and the panniers were now hanging on the frame by bits of wire. Schwinn looked about ready for the knacker’s yard.

A year later, Marjorie still had the bike in her garage.

First, six days out of San Diego, our Perkins 4-107 diesel engine went. We had been running it a couple of hours a day to keep the ship’s batteries topped up. Twice it had spewed black fumes into the cabin. A quick inspection showed the thing was coated in grime and leaking in several places. Why hadn’t the Perkins been cleaned and serviced in L.A. or San Diego?

“Air bubbles in the system,” Larry deduced. “Just needs bleeding. Have to wait for the seas to quieten down to do it.” The seas were “confused,” according to Larry. We’d had nothing but confused seas since leaving port. Our last stable image was of five harbour seals napping on a red buoy just beyond the breakwater. The waves seemed to have lost their logic. They came at us from all directions, lifting the bow abruptly, washing over the stern, thumping the sides. Some crested near the boat, the wind picking off the spray and flinging it in our faces. On night watches (four-hour stints), I sat nervously behind the wheel, listening to the waves flaring into foam next to my ear, waiting for one to turn the cockpit into a bathtub. The wind was just as mysterious, gusting one moment, calm the next. The sails filled and flopped, filled and flopped. Tebrinda pitched and yawed and rolled and groaned. Everything inside her rattled and banged. The sky was grey, glazed lighter where the sun was. We looked to windward for dark smudges drifting towards us signalling the next squall. We lived in safety harnesses and oilskins.

“It’s like being in a goddamn washing machine,” Josh said, after eight days of being tossed about and soaked, tired of picking things up off the saloon floor and wedging them somewhere.

“It’ll be different when we get closer to the equator,” Larry assured us. “Once we hit the 20° line, it’ll be all fair trade-wind sailing to Hawaii.”

Each morning, he presented me with a plastic bowl of his honey-coated granola with a pink slug of strawberry yogurt asleep on it. I tried not to look. I had brought some weapons to combat seasickness, bags of potato chips and saltines that I kept within easy reach just inside the companionway to salt my stomach. They were useless in these conditions. Josh had been ill, too, but not Larry. I tried to visualize the idyllic sailing conditions further south. Sunshine, a steady, warm breeze wafting over the stern, a gentle rhythmic rise and fall in the swells. I said, “I love granola. I have always loved granola” to the horizon. We struggled southwest.

No engine meant no battery power. No battery power meant no autopilot, no radio, no lights, no bilge pump, no music. Fortunately, Larry had this eventuality covered. He had brought along an emergency portable Honda gas generator with leads that could be hooked up to the ship’s batteries. There were problems with this generator, though. It had to be lashed to the deck outside and kept dry. It emitted fumes, which, when the wind was blowing from the wrong direction, made us all feel queasy. Also, running it three hours a day provided only enough electrical power for essentials: G.P.S. fixes, brief weather updates on the radio and a light to cook dinner by. Contact with Bravura was kept to a minimum. Our “buddy” was already out of sight.

The second thing to go was the Genoa. It took me a while to understand what had happened. I came up on deck on the eleventh morning to find the sail no longer flapping unhappily from the forestay. It was now on deck, a loosely rolled carpet tied to the port guardrail.

“Jib-reef broke last night,” Josh said grimly. “Gonna have to run on the main and the mizzen.” The jib-reef, as Bud Tritschler had taught me in my self-directed Cape Town cram course, was the rope running to the spring-loaded drum at the base of the Genoa. Pulling on it reefed in the sail. It was under enormous pressure most of the time and was therefore double-braided — it had an inner core and an outer skin. Tebrinda’s jib-reef was old. The core had pulled out of the skin, and all tension on the drum had been lost. I went up to the bow to look at it. The last two metres were like a stamped-on snakeskin.

There was no spare jib-reef on board, but we might’ve replaced it with another rope had something else not gone wrong at the same time. The Genoa is held aloft by a rope called the jib halyard. The jib halyard is attached to the top of the sail by a shackle. That shackle was now on deck, bent and pinless. With the sudden loss of tension on the drum, the sail must have rapidly unfurled and broken or dislodged the shackle pin. The Genoa had collapsed, while the end of the jib halyard remained at the top of the mast. One of us had to go up the mast and replace the shackle.

“We’ll hoist someone up when the seas quieten down.” Josh and I looked at Larry, wondering who that someone would be.

The loss of the jenny was not critical, but it would slow us down. Not that we had been making lightning progress: four or five knots an hour compared with Bravura’s six or seven. The larger boat nobly stayed within VHF radio range, no doubt wondering why she had agreed to a buddy-boating arrangement with such an unequal partner. It was time to let her go.

“Yacht Bravura, this is Tebrinda. Hi, George. Listen, can we get some water before you take off, over?”

Tebrinda’s third problem, which had announced itself on the very first evening of the voyage, was a tainted water supply. The tap over the sink in the galley coughed, spluttered and spat out a cloudy yellow liquid containing flakes of rust and fibreglass slivers. I swilled it around a bit in my mug. Probably as delicious as Beast of the Sahara radiator coolant. Had the owner been drinking this? Seemed as if the water tank had not been flushed out in years. I knew that fresh water had gone into the tank — I had filled it myself on shore. The rough conditions must have stirred up debris sitting in the bottom. Josh tried filtering the water through his handkerchief, which got rid of the larger matter, but still the water was foul and full of bits.

The Float Plan said we had seventy-five gallons of water on board. The ship’s water tank accounted for forty-some — neither Larry nor Josh knew exactly. The rest was sitting on the cabin sole in 2.5-gallon jugs that Larry had thought to pack as a backup. By day fourteen, we were halfway through this supply. To make the situation a little more acute, I had left the cap loose on one and, before anyone noticed, the thing had half-emptied itself over the cabin sole and some of Larry’s belongings. I was not popular that day.

On the day Bravura backtracked to help us, the wind and waves were calmer, the sky sullen. She came within hailing distance.

“VEE DON’T GET CLOSA. MAYBE YOU HAF SCURVY!” This from a Finn on board. Coming alongside was out of the question: Tebrinda and Bravura would bang and scrape each other. Coming to within ten metres risked clipping masts as the two boats heeled. Best thing to do was swim the empty jugs across for refilling. As Bravura was equipped with a water-maker that could desalinate seawater, replenishing our supply of fresh water did not deplete theirs. Josh had the only wetsuit aboard. He breaststroked over with the empties, able to swim using both arms. Getting back was more of a challenge. The loaded jugs barely floated and had to be pulled or shunted through the water. Josh kicked and thrashed, scooping the water with his free arm, the other stretched out behind towing a submerged jug. Waves washed over his head, tried to rip the jug from his grasp. He blew out mouthfuls of water, gasped for air.

“Ten feet to go, Josh.” Standing on the stern ladder, I heaved each jug aboard when it was within reach. Larry tested for salt-water contamination. Josh got slower and slower with each run, an increasingly desperate look in his eye. After an hour, the job was done. Josh collapsed on deck, shivering. Bravura pulled away and raised sails. We did not see her again till Hilo.

“See that line of clouds?” Larry pointed at the horizon off the starboard bow. We raised the mainsail and mizzen. “Typical of trade wind conditions.” I could only see typical rain clouds. “By this time tomorrow, we’ll be at the on-ramp,” as if the clouds marked a freeway and we could expect to hit cruise control once on it. We were now at 19° latitude, our heading 260°, almost due west.

Things went well for almost a week after our rendezvous with Bravura. The sea remained moody, the wind fickle, but we managed five or six knots. I developed sea legs and an appetite. I started to write in my journal and read. Mornings began well. Coffee was excellent with hazelnut creamer (there was no fridge on board). A couple of times, Larry made pancakes for breakfast that we filled with slices of banana and drowned in syrup. Larry insisted on making all meals because the kerosene stove was tricky to handle. A little plunger at the front had to be pumped vigorously, then the burner squirted with alcohol before it could be lit.

“Don’t want you guys blowing us out of the water.”

I began to learn a bit about my shipmates. Larry was single and had always been single. He had delivered yachts to Mexico and once before to Hawaii. He had lots to say on many subjects, his favourites being gun laws in the States, ham radio, women, New Zealand — where he intended to emigrate “when the shit hits the fan” — litigation and diet.

“Scumbag comes on your property, you should be able to shoot ’im, no questions asked,” he said with a grin. “Man has a right to carry a gun, a right to protect his family.” Josh, who was married with three kids, nodded.

Larry had three guns but said he only used them to shoot cans. “Mexicans, Afro-Americans, Puerto Ricans.”

When it came to food, Larry’s body was a temple. I mentioned that I’d had an upset stomach during my travels. I should eat plenty of grains, nuts and seeds, he said, plenty of cottage cheese and omega-3 flaxseed oil. And take Chompers, a herbal body cleanser, regularly. Use only cold-pressed olive oil for cooking. I should steer clear of refined sugar, anything fried and all red meats.

“Red meat is the worst thing you can put in your mouth, Tony. The cooking process releases free radicals and free radicals create a chemical imbalance leading to carcinogenic deposits. Red meats also contain saturated fats that cause cholesterol build-up, leading to vascular disease. Now yogurt with acidophilus cultures stimulates the immune system to fight . . .”

Larry was a man with set ideas on how things should be. He liked everything to be in its place and things done his way on the boat. He snarled at us for putting stuff down and leaving it unattended, like half a cup of tea or a dirty plate. Loose ropes on deck had to be coiled and secured. His pencil crosses on the chart when he did navigation fixes were drawn with the utmost precision. It puzzled me that he was out here at all, in an environment that defied control and on a boat he didn’t know. Given his exacting nature, it surprised me that he hadn’t inspected the engine and the water tank carefully before leaving. Maybe “work commitments” had interfered with his usual preparations for a voyage.

Josh was a slim man, a little taller than me, with a square jaw and narrow eyes. With his moustache and tan, he reminded me of a porn star. He had been married since he was eighteen. He showed me a photo of his three kids nestled on his wife’s lap. He told me he and his wife had wanted only two, but doctors in Tucson had screwed up his vasectomy. His pet subjects were unexplained phenomena and close encounters of the third kind. He noticed I was reading Battlefield Earth, a science fiction novel by L. Ron Hubbard about aliens taking over the planet — a book I’d picked up from a second-hand bookstore in San Diego.

“Extra-terrestrials visit earth all the time. There have been tons of sightings of UFOs,” Josh said authoritatively. “The U.S. Government has the wreck of an alien spaceship hidden in the desert. Claimed it was a crashed weather balloon. They have bodies, too. Check out The Roswell Incident.”

On the twentieth night at sea, I was disturbed from my slumber by a sound that was not new to me. I had just knocked off after my midnight-to-four shift and was exhausted. Tebrinda was running just on her mainsail with a single reef. The air had turned cold and I’d been shivering while behind the wheel. Two savage squalls had drilled the deck, rainwater streaming down the sail and fountaining out at the end of the boom. I’d had a hard time steering. The wind blew strong, then not at all, then weakly, then suddenly strong again — especially before each squall. Waves knocked the boat off course. The main kept wanting to back-wind. A couple of times, it had. I’d had to turn the boat full circle to blow it back the right way.

I opened my eyes. For a moment, I thought I was back on Milkwood. A repeated crashing sound over my head shook Tebrinda to the core: a construction site crane was pounding us with a masonry ball. The boom was jibing. CRASH! Pause. CRASH! Pause. I waited for a little voice to say, “It’s okay. All under control now.” I lay in my bunk, not wanting to swing my legs out unless absolutely necessary. CRASH! Pause. CRASH! Pause. RIP! This last sound was unfamiliar, but I knew the one that followed: the sound of a sail out of control, flapping angrily in the wind. Feeling like death, I wrestled on my wet oilskins as the boat began to flounder and lurch, and scrambled out of pitch darkness onto the deck. Larry had beaten me there and was shouting at Josh.

“I mean, I just don’t GET it! How could you POSSIBLY have let the boom gibe like that! Please, explain it to me.” He accused him of sleeping on his watch.

I was relieved to see the boom still where it was supposed to be: fixed to the mast and suspended above the cockpit. But the mainsail was ripped in two, from luff to foot. Larry and Josh, on either side of the boom, were bringing down the tattered halves in fistfuls. I turned the deck light on and helped them tie it to the boom with the lazy-jacks. Hanging from the underside of the boom was a coil of snarled rope, a pulley and a slider. This was the boom vang — a rope between the boom and the deck that prevents the boom from gibing. The mainsail had back-winded violently enough to rip the slider from its rail on deck. The boom had then swung from starboard to port and back as the wind gusted over the stern. That the mainsail had ripped so quickly probably meant that it, like the jib-reef, was old and weak. Having secured the boom, we sat panting in the cockpit.

“We’re screwed,” said Josh, hunched over, looking at his feet.

“We’ll just have to run on the mizzen,” I offered, starting to feel queasy. An ugly dumpfing sound of water smacking hull had begun under the stern.

“The mizz-ern?” Larry, in a you’re-trying-to-provoke-me-right? tone of voice. “The mizzen only works with the other sails.”

“We’re screwed,” said Josh. “I’m going to bed.”

“We need to deploy the drogue,” Larry said quietly after Josh had gone. “Till I can figure out what to do.” It took us till dawn. Larry had never deployed a sea anchor before. I had never seen one. It resembled a parachute. Its lines got twisted on deck. We weren’t sure which side to deploy it on. We tried it off the port bow and it refused to deploy, wallowing beside the boat, scrunched up like a dead squid. Full of water, it was almost impossible to wrestle back on deck. We tossed it out to starboard. I couldn’t go back to sleep after these exertions. I sat in the companionway. Larry flaked out on the cabin sole. Had he shot an albatross on his last voyage?

Darkness thinned into another overcast day. Waves pawed Tebrinda, knowing it was a dead duck. I decorated them with half-digested remains of a spaghetti dinner. I thought of Wet Dream at Cabo San Lucas, hibernating safely behind the Baja California peninsula. Harvey drinking beer on a beach under the sun, arms round a couple of señoritas. Captain Tharaldsen on Hoegh Musketeer had probably made twenty round trips to Japan since we met. How bad a mess was I in here? It would seem that Larry had not thought to bring any spare sails. There was always the EPIRB. Set that off and out went an emergency distress signal to land. But that was for a capsize, surely. A last desperate measure. There were, no doubt, plenty of things to try before that. Still, I felt relieved to know it was there.

“We’re not going anywhere today.” Larry’s voice was raspy. Dirt from the cabin sole stuck to the side of his face. His eyes had crusts in the corners. He handed me out a bowl of instant noodles, the finest thing ever to pass across my palate. Josh surfaced from his berth looking guilty and morose. We muttered to each other, whiled away a day doing nothing. Snoozed, stared at the horizon. I stripped down for a wash, the cold seawater making me gasp. I scratched down a few notes in my journal. In the evening, Larry called Bravura. They were now three hundred miles west of us.

To my mind, we had to do one of three things. At the risk of injury, winch someone up the mast right away to re-shackle jib halyard to jib. Attempt to bleed the Perkins and, if that worked, motor till we got calm waters, then fix the jib. Sew up the two halves of the main, hoist it and pray it held. Larry did none of these things. He was up early the next day.

“Belgian waffles on the stove. Clean up when you’re done.” Josh and I looked at each other. Larry went out on deck with a knife. As we ate, we heard him unpacking the remains of the mainsail. He worked for several hours without telling us what he was up to and without asking for help. The result was the top half of the mainsail jury-rigged to the forestay where the jib had been, and the bottom half, still fixed to the boom, raised by means of our clothesline to the mizzen spreaders. Both had been put out to port. Tebrinda had two ratty-looking half-sails and, with the drogue back on board, could manage a knot and a half roughly west. I saw the skipper smile for the first time in a week.

“Should make Hilo by the turn of the century.” Now I understood why Larry was out here. Sailing was a test of his resourcefulness. The main now resembled the sail of a Chinese junk, the new foresail a medieval jousting banner. Strands from the ripped edges of the sails danced gaily in the breeze.

We crept along for a couple of days, the sea flattening out, the winds, suspiciously like trade winds, blowing steadily from the east. Larry went digging in the forepeak locker.

“I have . . . a little trick up my sleeve,” he admitted with a chuckle, a plump sack like a bag of laundry in his arms. “This is gonna be our express ticket to Hawaii.” He’d bought it at a yachties’ swap-meet in San Diego. A spinnaker. Removing the jousting banner, Larry somehow managed to hoist it up the forestay, while Josh pointed Tebrinda into the wind.

“Ready,” called the skipper, two ropes now running from the bottom corners of the sail down the sides of the boat. Josh turned the bow tentatively back in the direction of Hawaii.

The spinnaker billowed out richly in front of the boat, an enormous wind-bloated triangle, bold white marked with red chevrons. A beauty of a sail. Probably about the right size for Bravura. The speed shot up. Three, four, six, eight knots. The bow sliced through the water and a foamy wake bubbled astern. I sat down and braced myself. Nine knots, ten, eleven. Too fast. A wumpfing sound began as the bow dug into the waves, disappeared for a moment, then heaved up a noseful of sea-water and tossed it into the air as it rose. We took cover under the spray dodger as the wind caught it and threw it back into the cockpit. I waited for something to twang, crack or rip. We jerked forward as Tebrinda buried her nose again.

“God-DAMMIT!” Larry let rip. “I was reLYing on that thing. Head off. HEAD OFF, Josh!” Josh wrenched the wheel round, and as the boat reluctantly turned north, the spinnaker sulked, then flopped down into the sea. There was a short silence.

“Perhaps you could cut it, make it a bit smaller?” Larry fixed his eyes on me. For a second, I thought he might hit me.

“That, Tony, my friend, is an AERODYNAMICALLY WIRE- TENSIONED FOIL, for CHRISsake!” He marched up to the bow and began hauling it in.

Our twenty-fourth day at sea was calm enough for us to winch our lightest crew member up the mast: Josh, despite my recent diet of saltines and instant noodles. He took a new shackle with him and reunited jib halyard with jib. The job was done in half an hour, and morale rose aboard yacht Tebrinda as the Genoa flew again and we averaged five knots for three days. During night watch, I was able to pick up a Hawaiian radio station on a little portable radio that Josh had brought along. “Crater Ninety-six, the best music mix.” Hawaii began to feel as if it was just over the horizon.

Then we were back on the jellyfish. A forty-knot wind came barrelling out of the west and stopped us dead in our tracks. More dumpfing. With clucks of exasperation, Larry fired up his Honda generator to get some battery power, then slouched in a corner with the radio, calling people in distant places. He was a licensed ham operator and had an antenna high up on the standing rigging. He found a Japanese man called Masayuki in Hawaii, someone called Patrick Ruthers in Alaska and a Stan Shuttleman in New Zealand. Larry made it possible for Josh and me to phone home through a ham operator. His call sign was J9DYF.

“Hi, Stan, this is Juliet Niner Delta Yankee Foxtrot. Still out here. Wind in the teeth. Thinking of moving to New Zealand. You know of any good real estate near Wellington?”

After two days, with no sign of change in the weather, the three of us decided on action. It was the first meeting of captain and crew to discuss strategy. Food and water were not problems at present, but sitting around suffering the sickly motion of a wallowing vessel was depressing. How about striking north or south? Try and steal a bit of westing whenever the wind would allow us. Why not? We heaved the drogue out of the water. North.

Twelve hours later, in the middle of the night, the storm was upon us. It began on my watch. What I supposed was just another squall did not pass in fifteen minutes. Rain settled in and became a downpour, the wind did not ease back. I turned round to check that I was tethered securely to the taffrail. Waves got bigger, their tops splitting into foam. Tebrinda began to pitch and roll dramatically. A particularly large wave slammed into the side of the boat, making me stumble. Larry’s head appeared in the companionway.

“Better get the jib in.” He came on deck with Josh, both harnessed and in oilskins. Neither had been able to sleep. They shortened the jib to the size of a beach towel. Heavy rain became lashing rain, making a percussion sound on the surface of the ocean. The wind whistled, tore at the rigging, warped the spray dodger, tried to push us over. We took turns at the wheel. The jib was shortened to the size of a pennant. A wave mounted the port gunwale and swamped the cockpit. Josh came to the helm. A second after he clipped on to the taffrail, a bigger wave washed in, knocking him off his feet. Now we were in the washing machine for sure. I had the feeling Tebrinda was being sucked into a vortex.

I had not been in a full-blown storm at sea before. Not with tall, wind-whipped waves, thunder and lightning. It was exhilarating, especially after two days sitting about on the drogue, trying to read, listening to the incessant clattering of halyards against the masts. I no longer felt seasick. I had to work my leg muscles to keep balance; I had to concentrate hard when I steered. I needed to watch out on all sides.

Lightning struck. Bright white bolts branching down the black sky off the starboard side, day-lighting the foam-streaked sea, a spectacular, startling display of raw energy, followed by violent timber-splitting cracks and claps of thunder. The lightning seemed far off. Then it was near. It lit Larry’s face as he steered, a pale oval in the recess of the hood of his oilskin, eyes wide, cheeks hollow.

“HELL OUT OF HERE,” was all I caught above the howling wind. Tebrinda came full about and fled south. Sixteen hours later, on our twenty-ninth day at sea, Larry drew a neat cross on the chart right over the one he’d drawn on the morning of our twenty-sixth day at sea.

The Float Plan allowed eighteen to twenty days for the passage from San Diego, California, to Hilo, Hawaii. We took thirty-five. The wind came around on day thirty and blew consistently from the northeast for the final miles. Tebrinda continued to disintegrate. Next to go was the wheel. It got stiffer and stiffer until it took two hands and sometimes a foot to turn it 30° either way. I didn’t mind the exercise it gave my shoulders.

“Storm probably bent the rudder shaft,” commented the captain. “Or else the pounding we took while we were on the drogue did it.”

Then the stove. The plunger dropped out the front one morning as Larry was pumping it. We took turns peering into the hole; we could hear an irretrievable nut rolling around inside the stove as it gimballed. It would have to be taken apart to be repaired. That meant no revitalizing coffees with hazelnut creamer to start the day; it meant instant noodle bricks crunched up unboiled; it meant cold meals eaten from the can with a teaspoon. A rogue wave butted the boat one evening while I was on watch, knocking a can of cold Dinty Moore stew from my hand. I laughed. I’d had my eyes closed while spooning in the limp cubes of carrot, the congealed gobbets of beef, the globules of solidified fat.

Screws securing the VHF radio fell out, causing it to crash to the floor and crack the plastic on the channel selector; screws securing the hinges on one of the cockpit lockers fell out, causing the lid to slide onto the floor. Water dripped in through two holes in the saloon roof. In troubled dreams, I saw myself leaping between constantly dividing sections of Tebrinda, clinging finally to the largest chunk and kicking hard for shore like Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss at the end of Jaws.

Hawaii Island, the largest and easternmost island in the Hawaiian group, did not introduce itself to me as a nut on the horizon as St. Helena on the Atlantic had. I got up on March 12, looked west and saw haze. The G.P.S. said we were thirty-two nautical miles away. An hour later, after breakfast, I looked again and saw haze. The G.P.S. said we were twenty-seven miles away. The “Big Island” is indeed big: hundred and forty-nine kilometres long, hundred and twenty-two wide, with two enormous volcanoes on it over forty-three hundred metres high. I didn’t want to say, “So where is it, then?” to Larry, who was glassy-eyed and looking peevish, having insisted on spending the entire night on watch. At twenty-two miles, I realized Hawaii was right in front of us. The haze became striated, took on dark wooded patches. I could make out the sides of a volcano. I felt a tide of relief wash over me. I felt giddy. First land I’d laid eyes on since acknowledging that a dark smudge off to port a few days out of San Diego was probably the Mexican island of Guadalupe. Today, I would walk on land for the first time in more than a month.

Yachts seek refuge in Radio Bay near the Big Island’s main town, Hilo. Dopey and careless, we missed the red and green buoys marking the entrance through the breakwater and found ourselves, engineless, being blown towards the beach. We dropped the Genoa. There was only one thing to do.

“Yacht Bravura, this is Tebrinda. Hi, George. Listen, can you come out and give us a tow, over?” An embarrassing request. As embarrassing as asking him for a water top-up in the middle of the ocean. We were too zapped to care.

There was no yacht club. Yachts moored in front of a brick toilet next to a fuel depot. There was a shower. I tried to walk straight, towel under my arm. My head pounded, my ears were blocked, I couldn’t see properly. Someone took a photo of us. I looked at myself in a mirror. A shiny face with a matted beard stuck to it stared back. I thought a freshwater shower after a month of putting the occasional bucket of seawater over my head would be ecstasy. I’d had dreams about it. Closing my eyes made me feel worse. I felt sick. I tottered.

In the evening, the three of us stumbled into town, stopping at the first restaurant. Larry treated us. Soup, steak, salad bar, apple pie and ice cream. He didn’t worry about free radicals. I ate the food but didn’t enjoy it. It was too rich, made me feel sick.

“Well, we made it, guys,” Larry said. Josh and I nodded grimly. Now was not the time for a post-mortem.

Back on the boat, at midnight, I was wide awake. It was my watch. I sat in front of the toilet, doubled over with stomach cramps, the sudden glut of food too much for my shrunken, shaken stomach. I looked out to sea, unable to think of much. A squall blew through drenching the yachts. I looked out to sea.