I spent five weeks in Hawaii: two on Hawaii Island, two and a half on Oahu, three days sailing between them. It was good to get away from the boat, put a bit of space between myself and the other two.

On the Big Island, I walked up and down the streets smiling at the green lawns. I ate beef burgers and ice creams — several a day. I went to Hilo Public Library and read The Roswell Incident from cover to cover. After a week, I sneaked aboard a tourist bus laid on for a visiting cruise ship to the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory in Kilauea Caldera. I thought the guide waving the flag at the door of the bus would rumble me — one skinny, bearded man in a shabby T-shirt, shorts and flip-flops queuing next to rich retirees with big stomachs and cameras and friends. I followed close on the shoulder of a woman in a floppy yellow hat and nodded vigorously when she spoke, put my head in my day sack as though searching for something as I stepped aboard.

It was odd to find large volcanoes in the middle of the ocean so far from tectonic plate boundaries. A National Park Service pamphlet handed to me at the caldera said that the Hawaiian chain was formed out of magma from a “hot spot deep within the mantle.” Fluid rock created a seamount on the ocean floor. “After several hundred thousand years and countless eruptions, the volcano rises above sea level to form an island.” The long, uniform days at sea made me hungry for facts like these, fascinated by gazing down into an eight-hundred-metre pit of boiling mud called Halemaumau Crater, raring to walk the Crater Rim Trail. The rush of information to absorb, the visual stimulation, the physical exertion — I was happier than when Milkwood made landfall for the first time at St. Helena.

Josh flew home from Hilo. After the short sail to Oahu, Larry flew home from Honolulu (“work commitments”), Honda generator under one arm, aerodynamically wire-tensioned foil under the other. Hans Hoogeveen, the owner, would fly in and take what was left of his boat the rest of the way to Saipan. I was alone on Tebrinda at Hawaii Yacht Club at Waikiki, having promised to stay till Hans showed up. I watched the first trickle of yachts arrive from Baja California. Enchantress, a gorgeous fourteen-metre sloop, had been in the next slip to Wet Dream at Kona Kai Marina in San Diego. No news of Harvey. I looked for a boat to carry me further west. Domineer, a German yacht, was going to Tahiti but didn’t know when because the skipper’s wife was pregnant. Dose of Salts was also heading south and wanted a hundred dollars a week from crew.

Finding the right boat would take time. I had to work, not let the cash I’d made dwindle away. The Hare Krishnas in San Diego had given me the phone number of a Hawaiian called Kimo, a former male stripper who now worked for the Green Cross Foundation, an “environmental” group similar to the one in San Diego. Green Cross had tables at the base of Diamond Head Crater, a two-hundred-and-sixty-metre extinct volcano near Waikiki. Because I spoke passable Japanese, Kimo offered me a job. With a string of beads round my neck, I persuaded visitors to buy T-shirts before they walked the trail up or when they came back down. Sometimes I worked with Jake Tai from Maui selling “Certificates of Achievement” and bottled water inside a bunker at the top of the crater. The Honolulu Advertiser reported that Green Cross pressured visitors to make purchases. A picture of me with my beads coaxing a woman to buy a certificate appeared on the front page.

‘“We don’t appreciate being hustled by vendors,’ said Pauline Harrington from San Diego, after making it into the shade of the defunct coastal defense bunker,” the reporter wrote. The police descended the following day, told us to pack up and leave. Working without a green card, I didn’t need to be told twice. But four days’ work made me $320 richer.

Hans was sixty but looked younger. Tanned, radiant face, big smile full of white teeth, not an ounce of fat on his body. He wore flashy sunglasses, slacks and a sleeveless shirt with a big open collar showing off his greying chest hair. He had been on Saipan for two years, had moved there from L.A. after a messy divorce. Tebrinda was a name he’d concocted by combining letters from the first names of his three children: Terri, Sabrina and David.

“You gotta come to Saipan, Tony. Nowhere on earth like it. It’s clean, no big ports, no industry. A tropical paradise. Great bays for swimming, great golf course, great diving. I have a house with the best view on the island. Papaya trees in the garden — if the cow hasn’t eaten them. Flame tree, too.”

“A flame tree?” Hans and I were spending our first evening together at TGI Friday’s in Waikiki.

“Flame trees all over Saipan. And, you know, it’s a historical place. Japanese invaded the island during the Second World War. There’s gun emplacements. And a tank. You gotta stand on Suicide Cliff. Japanese soldiers threw themselves off Suicide Cliff rather than be captured by the Americans.”

Before he left, Larry had told Hans precisely what had happened to Tebrinda during the first leg, blow by blow. The facts had seemed to bounce off him. He’d repair everything, he said, no expense spared. I wanted to ask Hans how much sailing experience he had had — other than his one aborted mission with Tebrinda. But it didn’t matter. I’d be a fool to sail any further on this boat.

A crane heaved Tebrinda out of the water and put her on a wooden cradle so the rudder and hull could be checked. Nothing wrong with the rudder. After a good rinse in fresh water, it turned freely. After an oiling, the wheel could be spun with a little finger. Tebrinda went back in the water. Having nowhere to go, I agreed to stay on board for a while to help with repairs. A week passed. I visited yachts up and down the slips. Bright Silver Fox from Mexico, final destination Hawaii; Fast Forward, a catamaran, bound for the Philippines, not looking for crew at present but might be in a few weeks. Hans bought a new mainsail and a new Genoa. I helped him hoist them on new ropes. He bought a spare Genoa. He bought a new autopilot. A mechanic came by to service the engine and fix the stove. After a clean and a tune-up, the engine was fine. With a pair of pliers, I bent the boom vang slider into shape. It now ran happily along its rail. Hans put new screws in the radio and cockpit locker lid. I opened up the water tank, cleaned it out and disinfected it.

“Did you drink from this tank when you sailed from California, Hans?”

“Yup.”

Tenacious, a ten-and-a-half-metre sloop for Tahiti. No. Deck piled with junk. Aquila. No. Skipper an arrogant snob. Hans and I went shopping for provisions. We humped jerry cans of fuel and water aboard. Hans caulked the holes in the saloon roof. We tested the new sails in Mamala Bay in front of Waikiki, we rigged up and tested the autopilot. We went for dinner in the evenings at TGI Friday’s.

“So, you coming to Saipan or not, Tony?” I groaned. Looked across at the chipper sixty-year-old grinning away at me. We’d had a few beers. Why the hell not? I had travelled through thirty countries, across one and a half oceans and was still in one piece. Why had I set out from England if not for an adventure? I was inclined at this moment to think of destiny. My search for freighters in Vancouver had been fruitless and no one was heading to Japan from here. Everyone wanted to go to the yachties’ play-world, the South Pacific. But what about this man sitting opposite me? That was what was important. He didn’t seem to have Larry Roberts’s nautical expertise, but, unlike Larry, he was easy to get along with, keen for help and open to suggestions about how to do things. I had been more involved with this boat over the past week than I had during the previous two months. You should really try and learn from your mistakes, Tony, said the voice in my head. Hans had no Float Plan. He’d never owned a boat before. His last voyage had been a failure. There was no point in asking him if he was a competent sailor. If I had been sitting on the other side of the table, I would have bullshitted.

“On one condition. Two, in fact,” I said, leaning forward emphatically. “We find another crew hand and we stop off at the Marshall Islands on the way.” Hans called a waitress over for the bill and asked her if she liked sailing.

The day before we left, I went over Tebrinda with a fine-tooth comb. Perkins on, Perkins off. Perkins on again. No smoke, no leaks. Perkins off. Jib-reef secure on the drum at the front. Water tap on. Not a shard of fibreglass, not even a speck of dirt in the mug. Water tank full to capacity. Spare jugs on the cabin sole tied together, caps tight. Boom vang tight. Stove plunger plunging smoothly. Everything put away, wedged in, tied down. Perkins on, Perkins off.

No one wanted to come with us.

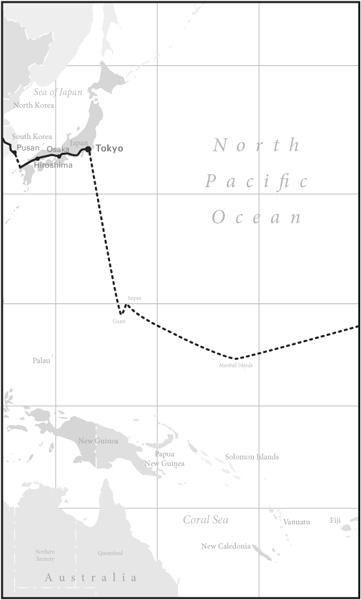

Tebrinda left Hawaii on April 17, 1996, and headed southwest. It took her fifteen days to cover the nineteen hundred nautical miles to Majuro Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The first night gave me the willies — while Hans was vomiting, while the boom was gibing, when I put my weight on the top wire of the guardrail and it twanged slack — but after that, things were fine. To my astonishment, I was not seasick. A yachtie had recommended Bonine. Sounded like a dog biscuit. One pill before we set sail, another before bed the first night. After that, Ka Po Preserved Mandarin Peel that Hans’s girlfriend, Yu Ming, had given him for the voyage, a mixture of dried orange peel, licorice, citric acid and salt. Hans avoided the stuff, saying it upset his stomach. It tasted disgusting and worked perfectly.

But it was really the wind and sea that worked perfectly. Winds at a constant ten to twenty knots out of the northeast. Boat speed a steady six knots. Two-knot current carrying us in the right direction. Affable, rhythmic swells gently lifting the stern and causing us to surf. Surely this was a different ocean. A well-equipped, well-prepared boat makes for a good crossing, but the success of the voyage is really down to timing. Joshua Slocum, the first man to sail alone around the world, crossed the Pacific from Tierra del Fuego to the Marquesas on a ketch the size of Tebrinda in May 1896. “Nothing could be easier or more restful than my voyage in the trade-winds,” he wrote in his log. In July 1965, sixteen-year-old Robin Lee Graham, the youngest man (at that time) to sail alone around the world, set out from L.A. on a eight-metre sloop, headed for Hawaii. “The voyage to Hawaii was almost too easy,” he reported. “The Pacific can be like that — days of sailing in nothing but four-foot swells and winds of fifteen knots. Dove behaved well and so did the kittens once they had gained their sea legs.” Larry and Josh should have stayed on board Tebrinda.

Larry may have been slapdash in his preparation of the boat and unwise, perhaps, to try crossing the ocean so early in the year, but he could cook. On our first morning at sea, sun splashing the wave tops, Hans presented me with a shiny beige turd curled up on a plate. Less than a turd. A flattened turd, decorated with pimples. I prodded it with a knife. Some species of tropical sea slug. I looked up at the man responsible for this culinary catastrophe. He waved a dripping spatula at me.

“Well, the mix is no good, see? It says you gotta use eggs and fresh milk and butter.” I could not think of a suitable reply. I saw a month of ugly meals ahead of me. Now why hadn’t I asked Hans on shore whether he was a competent cook?

“Next time, we’ll have blueberry pancakes, okay? I can do those,” Hans said, watching me dig in a cupboard for granola. From then on, I made every meal. Three a day, day in, day out (including my birthday), all the way to Saipan. I hated cooking on land, but at sea it gave me something to do and, ironically, took my mind off my stomach. Teb was now overloaded with food, far more than the two of us could get through. Pasta of varying types, rice, couscous, a hundred cans of stew and sausages and vegetables and soups. Chef’s specialty was pasta spirals in tomato sauce, with tinned tuna or chopped wieners and mixed veg stirred in. This dish sat well in both our stomachs. Fresh fish would have been nice, but for some reason we could not figure out, the line we were trolling off the stern did not score, whether we baited it with fake sardine, silver foil or wiener.

I didn’t see much of Hans. We had meals together, but during the day, Hans liked to sunbathe on the foredeck while I preferred to read in the cockpit — my big book for this leg being Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. We slept at different times during the night. Hans was on watch from six p.m. to midnight; I did midnight to six. With the autopilot steering, no traffic about and balmy weather, we both tended to catnap on watch. Six hours was too long to remain alert and vigilant. Hans called Yu Ming on SSB radio before his night watches.

“How are you are you feeling fi?” was the way Yu Ming began each conversation with Hans. She was seventeen years younger, a Chinese woman who had come to Saipan to work in a garment factory. Now she lived with the American, cooked for him and studied English. Hans quizzed her on the domestic situation at the Hoogeveen residence.

“That cow keeping the grass down? Keep him away from the papaya.” “How tall’s the bougainvillea?” “Remember to hose Gerri down at lunchtimes. He isn’t fond of the heat.” “Lucky sleeping under the car?” “Don’t let Lilly in my bed, you hear!” Hans was a computer programmer helping the government of Saipan computerize its tax system, but it sounded as if he lived on a farm.

Tebrinda crossed the International Date Line on April 29, 1996. I was halfway round the world. My adventure so far had taken me two and a half years. A few days later, I spotted green eyebrows floating on the horizon. As we got closer, they became punk rocker mohawks, then coconut palms sprouting from tongues of white beach. The Republic of the Marshall Islands, named after British captain William Marshall, who passed them on his way from Australia to China in 1788. There was none of the drama of gazing up at Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea while approaching Hawaii Island. These coral atolls were long-extinct volcanoes, now practically submerged, their cones barely breaking the surface. They have odd names — Rongclap Atoll and Wotje Atoll and Kwajalein Atoll — but the best known is Bikini Atoll, the site of atomic bomb tests between 1946 and 1958. The Parisian designer Louis Reard named the bikini after the atoll in 1946, reasoning that the burst of excitement the new swimwear would generate would be like setting off an atom bomb.

I was hoping to do a bit of snorkelling in the Marshalls. My pamphlet about the republic from the Marshall Islands Tourist Office in Honolulu showed pristine beaches and undisturbed green lagoons. There were twenty-nine atolls in the group, it said, “the most perfect tropical atolls on earth.” Shots from the air made it look magical.

We stopped at Majuro Atoll, where most of the islanders live, entering the lagoon at night — something you should do only if you have a boat with a ferroconcrete hull. There is only one entrance in the coral ring; the G.P.S. guided us to and through it, metre by metre. We put in to shore with the new day and tested our legs around dilapidated buildings and water towers with rusty legs, around long-ignored heaps of domestic refuse piled against chicken-wire fences. On the beach, piles of abandoned fishing tackle, fish heads, scrap wood, coconut husks and beer cans. No one sunbathing in a bikini. I decided this wasn’t the spot to strip down and hunt for clown fish and turtles.

“Uncle Saaam supports the Marshalls, mate,” said Frank Mertle, from Perth, Western Australia, a seventy-four-year-old with liver spots on his face. He was on the only other visiting yacht. We hailed him and he came over in his dinghy for tea.

“Islanders live on U.S. food stamps. Grow nothing, make nothing, do nothing. ’Cept fish. Rely on the blady supply ship.” We nodded. I wondered just how much could be grown on narrow spits of sand crowded with palm trees.

We went to Majuro’s sole supermarket and bought a head of Chinese lettuce for $10, a small cucumber from California for $1.50. Everything on the shelves was imported. Outside, we sat at a table and watched wild-haired and sun-scorched Majuran men in ragged T-shirts smoking and playing checkers with lumps of coral.

It would have been nice to compare Majuro with one or two of the other atolls. No doubt Wotje Atoll was different, more “perfect” perhaps. I would never know. Hans was itching to get home. No more stops.

Teb headed northwest to the Commonwealth of the Marianas and Saipan, past Truk and the Caroline Islands and over the deepest trench on earth (almost ten thousand metres deep in places). Fourteen days to do thirteen hundred miles. Gentle swells, families of flying fish skipping and gliding over the waves, the soothing swish of water round the hull. I dozed and dreamed. Began thinking about Asia. Yu Ming’s voice got louder each evening on the radio.

“How are you are you feeling fi? I miz yu.”

“Yes, yes, my dear. Just a few more days to go now. You know what we’re gonna do, you and me? Sail to China and see your parents.”

I thought about finding someone to travel with. In the Americas and Canada, I had spent a lot of time exploring alone, standing on empty roadsides with my thumb out, cycling long kilometres jabbering away to myself. Meeting people briefly, moving on, meeting more, moving on, a constant stream of new faces. It was good to get impressions of a multitude of different lives, and I enjoyed being a passing novelty recounting my adventures, but making acquaintances and saying “so long” the following day, again and again, was also wearing. Sometimes I felt detached and lonely.

I’d had several temporary companions — other travellers I’d bumped into on the road who happened to be heading my way for a while. I remembered them with affection. Bright in Algeria, Olivier in the Congo, Mike Smith on the Atlantic, the group I’d hiked with to Machu Picchu. Sailing had been a good way to get to know one or two people — more intimately than I wished to in some cases. Sailing across an ocean took time and it happened in a tiny, shared space. No doubt Larry and Hans would lodge themselves in my memory. How would it be to share all my discoveries in Asia with one person? A more permanent companion. A risk. The right person would lead me down some interesting pathways, draw my attention to things I would otherwise pass by, make me think in an alternative light about what we saw. The wrong one might be uncompromising, might resent the whole no-aircraft project, might whine when the going got tough. Did I really want to give up my liberty, the control I had over my wanderings?

My temporary companions had nearly all been men. Travelling with a woman might be a welcome change. I’d had a few flings since setting out. An English girl in Kenya, a German called Petra in Mexico, a Bolivian journalist on Lake Titicaca, a Brazilian I met on an overnight bus to Boa Vista from the Amazon. I’d seen Petra again in the U.S. and Canada, but we had fallen out. Then there was Nadya Ladouceur, the French Canadian I’d stayed with in Montreal. Was she still in her little apartment on Rue de la Visitation? On Saipan, I decided, I would write a letter to her, invite her to join me somewhere in Asia.

There was a flash of light in the night sky off the starboard bow at 3:10 a.m. on May 19. The light dimmed, then flashed again, dimmed, flashed. I rubbed my eyes, got up and checked that the autopilot was on course. Steady at 290°. My voyage with Teb was almost over. At dawn, two inviting beds of land reclined on the water ahead, pillows of cloud suspended over them. Saipan and its neighbour Tinian. If I was ready to believe that the Philippine Sea lay beyond them, then I was almost done with the Pacific Ocean.

“Blueberry pancake?” There had been some clattering in the galley before my watch ended. Hans had got up early. On the plate was a large dry ear, decorated with blue studs. On our last day at sea together, he wished to treat me. I looked over at Saipan. Hopefully, it had one or two decent restaurants, a supermarket without Majuran prices. I prodded the ear with a fork while two Saipanese gulls observed me from the mast spreaders.

“Everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask,” Hans said, handing me the Historic and Geographic Tourist Map of Saipan two days after we made landfall.

Saipan is the shape of a dog sitting up begging: coral-crusty nose at Lagua Lichan Point in the north sniffing the Pacific Ocean air, stubby tail at Agingan Point in the south wagging at the Philippine Sea. The dog informed me that Saipan is forty-eight square miles in area, enjoys an annual mean temperature of 83°F and has a 1,545-foot hump on its back called Mount Tapotchau, captured from the occupying Japanese by U.S. Marines on June 25, 1944. A box at the side of the map labelled “Helpful Information” told me that, as a non-U.S. citizen, I could stay for thirty days, another in the corner that the nautical distance to Japan is 1,272 miles. I would have to swim the distance. Tebrinda had pulled into the island’s only marina, Smiling Cove. There was no commercial traffic and no passenger link, and Tebrinda was the only yacht in the marina.

Hans’s house was a government building located on Capitol Hill, a little north of Tapotchau, one of several “built by the Central Intelligence Agency in 1957 as a site to train Chinese guerrillas” when Washington considered China a communist threat. A tidy, comfortable, solitary bungalow, painted white, with tropical plants growing along the side, lawn and papaya trees surrounding it — it didn’t look the part. Hans and Yu Ming lived with Lucky, an old spaniel, and Lilly, an affectionate orange tabby. In a pen in the garden, there was Gerri, the pet pig, and tethered to a tree, Bernard, a black and white cow that kept the grass down. The bungalow overlooked the west side of the island: a green lagoon below, dark blue sea beyond, a line of surf marking the coral separating the two. Warm breezes blew down Capitol Hill in the afternoons and evenings through the mosquito-net windows, making National Geographics on the coffee tables flap.

I stayed with Hans and Yu Ming for twenty-nine days — right up until I had to be off the island. I read under their flame tree, ate at Hans’s favourite beach restaurant, taught Yu Ming English, hosed Gerri and Bernard down to keep them cool, jogged up and down Tapotchau, snorkelled along the reef and prayed for a Japanese yacht to show up at Smiling Cove. Hans took me to Banadero Cave. “Last Command Post for the Imperial Japanese Army was a cave with fortifications where they resisted to the end.” The history part of the Tourist Map went into great detail about how the Americans had unseated the occupying Japanese forces during the Second World War (“Saipan fell on July 9, 1944, after 24 days of fighting”). Rust-streaked coastal defence guns pointed out to sea from the cave, a Japanese tank charged nowhere on broken tracks. We climbed Suicide Cliff, a sheer drop of two hundred and seventy metres to rocks. “At Suicide and Banzai cliffs, families lined up single file with each younger member shoved over the rocky cliff by the next older child. As the final act, the father would run backward toward the edge so as not to know his last step.” Thirty-one hundred U.S. troops died on Saipan, 29,500 Japanese.

It was a Japanese couple that got me across the final 1,272 miles of sea-water, but not from Saipan. Only one foreign yacht turned up at Smiling Cove Marina while I was there, newlyweds from Hawaii on their way to the Philippines, definitely not interested in having a lone Brit along for company. So I said a fond farewell to Hans and Yu Ming and boarded a small cargo shuttle to Guam, a hundred and twenty nautical miles south — a lift arranged for me by a colleague of Hans’s who was in the shipping business. Thanks to its U.S. naval base, the bigger island sees more trans-ocean traffic. Commodore George Johnson, in charge of the busy Marianas Yacht Club, permitted me to stick up my tent behind the club while I angled for a lift.

Koichi Kuga and his wife Tsuse were on the final leg of a voyage from New Zealand home to Japan on the brand new fourteen-metre yacht Hinano. I was alone in the yacht club one morning when a thin, sun-blackened man with big glasses and a mischievous grin entered.

“Where custom?”

“Koko ja nai yo.” Well, not here. I called the customs office and got a peeved man on the end of the line saying that he’d already told the Japanese precisely where to go: F4, the commercial dock, where all traffic has to check in and out.

There were three others on board Hinano: Matsuoka-san, a man with a round belly and a shock of white hair who spoke with his eyes closed and was referred to as Daima-chan (Dear Big Ma); Mister Yoko, a single woman in her forties, called Mister because of her impressive muscles; and a lad of eighteen with a peeling back called Hisao. As luck had it, Mister Yoko had phoned home from Guam to discover that her pet dog, Bibi-chan, was ill in Yokohama. She had to fly home immediately. I felt like laughing. Someone Up There must like me, and all I had to do was endear myself somehow to the captain. Dredging my memory for appropriate Japanese phrases and remembering that requests in Japan tended to have a better chance of being granted when made through an intermediary, I recommended myself as a replacement crewman to the captain’s wife.

“Tony-san, I hard your requesto,” Koichi said after a chat with Tsuse, the day before they intended to leave. “Ooookay. We cally your bags on Hinano today’s evening.” Not that the Kugas really needed a substitute crew hand. No muscles were needed to raise the mainsail: roller-furled into the boom, it was raised and lowered by pressing a button. And Hinano had Autohelm and an Aries wind vane, two self-steering devices. The boat could be kept on course by one person sitting in front of the radar screen inside. Maybe the crew had grown tired of each other’s company.

“Hisao pay ten dollar one day for eat,” the captain said once I was settled. “You pay onaji, daijobu?” The same, okay? I bowed. The typhoon season was near. On a boat this size, the voyage would take no more than a fortnight.

At the commercial dock on departure day, I helped Koichi do his paperwork in English and watched yellow-fin tuna being craned out of the hold of a fishing boat. A Japanese man supervised the work with a walkie-talkie. The metre-long fish, dangling and glistening as they spun in the morning light, would fetch as much as $10,000 apiece in Tokyo, the man informed us. Then one of them was ours. It had shark bites in the side, wouldn’t be any good for the Japanese market. Koichi quickly sliced the fish into cubes and strips, cubes for the freezer, strips to become tuna jerky in a mesh basket hung outside.

Koichi and Hisao disappeared briefly and returned with a trolley stacked high with Steinlager beer from the duty free shop. Eight cases. Two hundred cans. A lot, I thought, for a short journey.

“Now leady,” said the skipper with a smirk.

The voyage took a full month. The Ogasawara islands lie between Guam and Japan, and the Kugas knew people there. First, we sailed to Chichijima (Father Island), the largest of the group, and partied with a fisherman who used to be an office worker in Tokyo, then with a family who had spent years on the island and wanted to move to the mainland. A couple of hours from Father Island was Hahajima (Mother Island). Here we partied with another fisherman, Yamaguchi-san, who told us there was a typhoon on its way from the south. The Kugas would surely strike north for Japan directly.

Hinano set sail. Two hours later, we were back at Chichijima with three anchors down, ropes out to the nearest harbour buoys and to the quay, fenders out on port and starboard sides. Typhoon Ben marched through, strafing the island. Hinano went largely unharassed in her protected spot, recording wind speeds of 55 kph. A day later, the sea was calm again. Now we would head for Japan.

“Ja, Gleeeen Pepay mitai desho,” slurred Yamaguchi-san, our host. We were back on Hahajima, keeled over on straw mats, stomachs swollen with rice and raw fish, drunk on sake. Well, I guess you’d like to see Green Pepe, hey?

It was midnight. We shot off in two cars into the woods away from the coast. As we drove, I heard a repeated wet fart sound. Legions of frogs with yellow bellies were hopping in front of the headlights, going under the wheels and bursting. Splat. The driver made no effort to avoid them. Splat. Splat, splat. “Daijobu.” It’s okay. The island was overrun with the things, he told us, introduced to keep the mosquito population down.

The road diminished and died. We got out, tripping over roots and fallen branches, penetrating the woods in single file. The moon disappeared, but we could see by the pale green blobs of light at our feet. Green Pepe: delicate toadstools anchored to decayed logs, miniature glowing parasols. You could almost read by them.

“Doshite?” said Hisao, baffled at the natural phenomenon. How come?

“Wakanai,” said Yamaguchi-san. No idea.

Meguro was another resident of Hahajima, me meaning “eye,” guro “black,” a bright green and yellow warbler with a black mask, plentiful on this island but living nowhere else in the world. Meguro fidgeted about the bushes and liked to jab its beak into slivers of papaya the fishermen’s wives put out.

After the yo-yoing between Father and Mother islands, Hinano went north a bit, then spent a couple of hours circling Sofu Gan (Grandfather Rock), a splendid tooth of rock sticking thirty metres out of the sea. Incensed gulls screamed at us from ledges and dive-bombed the boat.

“Omoshiroi desu ne?” said Dear Big Ma to no one in particular. Interesting, hey?

“So desu ne.” It is, Tsuse agreed, as we went round for the third time. Feeling nauseous, I sighed. The Pacific was teasing me, making me earn every last mile. The delay is not important, I reminded myself. The rock was indeed omoshiroi — I’d not seen anything quite like it. I stared at it. I had had my fill of the ocean. I had the feeling I’d never reach the far side.

Next stop: Hachijojima. Koichi and Dear Big Ma decided that the seas were a trifle lumpy, that it would be nice to stop for a day and wallow in a hot spring bath.

Hinano finally arrived at Aburatsubo, a small town at the end of the Miura Peninsula and fifty-six kilometres south of Tokyo, on July 24, 1996. Everyone was glum except me. I was back in Japan. I stepped ashore, kissed the ground, had the impulse to bolt up the nearest mountain and yell hallelujah from the summit. “Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away.” Then I felt utterly drained of energy. God. Seven months to cross the Pacific Ocean. Damn yachts. Hated them. Bottled up, shaken silly day and night.

Forty of the Kugas’ friends came down from Tokyo for a welcome home party. There were Steinlagers to finish and tuna steaks. Koichi got blind drunk and fell off the dock.

I was broke. In Tokyo, I bought trousers with creases, a shirt with a collar, shoes and a tie. I shaved off my sea beard and got into the habit of showering daily and applying deodorant. Transforming myself into a respectable, sweet-smelling English teacher, I worked for two schools. Between ten-thirty in the morning and nine-thirty at night, six days a week, I corrected office workers’ grammar and pronunciation; I played telephone dialogues on tape cassette to attentive secretaries in black skirts and white stockings; I drilled handy idioms into university students (put up with someone, put someone up, put someone out). The Kugas were well connected and got me settled quickly. They knew a landlord in the suburb of Kawasaki willing to rent me an old apartment for $200 a month, a fifth the going rate. Another friend lent me a bicycle so I could get from the apartment to the nearest subway station.

It was good to be back in Tokyo, where I’d lived from 1988 to 1990: droves of people politely squashing onto trains, outsized TV screens showing film clips stuck to the sides of buildings, neon characters blinking in different colours. I nostalgically ate sushi and nato and shabu shabu, Japanese fondue. I played pachinko, a game like vertical pinball. Every three or four days I went to the sento, the public hot bath, and boiled myself. I looked up old acquaintances and drank Kirin and Sapporo beer. I dated an attentive secretary with white stockings. Bob Hornal from Vancouver showed up to teach for a while. Between lessons, I studied maps and guides of China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. On the packed morning train to work, I tried, with little success, to learn some Mandarin from a pocket self-study course pressed to my face.

I got a letter from Montreal. Nadya was surprised that I still remembered her. A year and a half had passed since we’d met. Travel in Asia together sounded like fun, but she wasn’t sure if she could just cut loose and do that. I phoned her. Why not join me in China and take it from there? I had bought a guidebook for the country. I waxed lyrical about the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, the Terracotta Warriors, the Yangtze River. After several calls and letters, she agreed to join me in Beijing in May. I was thrilled. For the first time, a companion to share my adventures, someone I had chosen and liked.

I quit work as soon as I’d made two million yen, £10,000, $15,000 — the amount I’d set out with originally. Enough to get me all the way home — via Australia — if I was careful (and didn’t keep backtracking to Hahajima). I converted most of it to pounds sterling and sent it to my bank in England. Seven months in a collar and tie was enough. It was March, the weather was warming up. I was itching to get going again. I threw my work clothes in the garbage. I went to the Kugas to say sayonara.

We hadn’t seen much of each other since the voyage. I’d been to their house a couple of times for meals, when they always had a gang of friends round. I admired them for being unconventional. Most Japanese thought about work and duty; the Kugas thought about how to avoid work and enjoy life. I thanked them for helping me out. Drunk, I said I intended to paddle through Southeast Asia in a canoe. To the Hovingtons in Quebec, I had been le cycliste fou. The Kugas called me hen na gaijin, the odd foreigner. As I set off to thread my way through the narrow streets back to the subway station, I heard Tsuse shout “Mata ne!” Till next time.

On April 2, 1997, I took a subway train to Ebina, a western suburb of Tokyo, climbed over the back fence of a service station on the Tomei Expressway, walked out onto the entrance ramp and held up a sign in Japanese: “Osaka.” It felt like a new beginning. Although it reminded me of standing on the M1 slip-road three and a half years earlier with my “Dover” sign, now I felt as if I could actually make it around the earth by land and sea.