“We could ride up on desert islands, string a hammock between two palm trees, crack a coconut, get naked, live like castaways. Wouldn’t that be just magical?” Somewhere in Southeast Asia, I wanted to buy a boat so we could travel under our own steam.

Nadya did not commit herself. “What . . . sort of boat?” We were leaning on a railing at the end of Queen’s Pier on Hong Kong Island looking at the boats in Victoria Harbour. Nothing suggested itself. White and green Star ferries shuttled back and forth from Kowloon. Motorized sampans with shovel noses, raised sterns and car-tire fenders puttered about. A junk nudged along, sail ribbed and brown like a bat’s wing.

“Dunno exactly. Canoe of some kind? Nothing motorized.” Something like the wooden ones I’d seen on the Ucayali in Peru, I thought. Or like those from the start of the 1970s TV show Hawaii Five-O I used to watch as a kid. I was after the freedom I’d had crossing Canada with Schwinn. Go anywhere, stop anywhere, be in touch with the natural surroundings. There’d be no trouble with waves like out in the ocean. South China Sea, Java Sea, Arafura Sea — all boxed in by islands. Sheltered coastlines. I pictured water gently unrolling like a new carpet onto smooth beach. Storm on the horizon? Just head for shore.

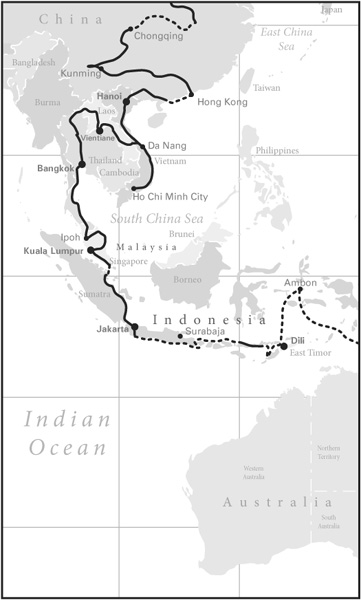

During the summer of 1997, the black line on my Times World Map wriggled south from Hong Kong. We rode in minibuses down Vietnam, bread vans along the rougher roads of Laos, buses in Thailand; we thumbed rides through West Malaysia to Singapore; we took a hydrofoil, then a ferry from Singapore to Sumatra, a bus and a ferry to Java.

I had an address to look up, a couple by the name of Ga whom I’d met in Tokyo, friends of the Kugas. Eiji Ga’s company was sending him to work in Jakarta for a year. He had given me his business card with his new address on it. “Ga mean mott,” Koichi had gurgled drunkenly in my ear.

Nadya and I stayed a week with Mr. and Mrs. Moth and their sausage dog, Gaku, in Kebayoran Baru, a suburb of Jakarta. They lived in a deluxe, air-conditioned apartment protected by a spiked steel gate and a three-metre wall crowned with broken glass. A guard let us in and out.

Jakarta was the most overwhelming and least appealing city I’d yet visited on my travels. Swollen with migrant workers from the countryside, it was clearly straining under sheer weight of numbers. The streets were choked with buses, bemo (open-sided taxi minibuses), bajaj (three-wheel motorbike taxis), motorbikes and crowds of people. Heat and high humidity made the smoggy air almost unbearable. Unlike Beijing, Jakarta appeared to have no real centre unless Merdeka (Independence) Square was it — a littered park with a hundred-and-forty-four-metre stone monument in the middle left by Sukarno, the first president following three hundred years of Dutch rule. Coughing, we were pleased to exchange the sweltering streets for the Gas’ cool apartment. I could feel a fresh bout of liuxingxing ganmao, the Chinese flu virus, coming on.

Mrs. Ga’s coffee-table picture books had other views of the country: volcanoes, paddy fields, white cloud drifting over densely forested mountainsides, shadow puppets, ancient temples, coral islands and wooden fishing canoes. I stopped at the canoes. Five to seven metres long, they were called prahu. We’d seen canoes of similar size in Vietnam and Thailand, but the ones in the book had bamboo outriggers and looked sturdier — capable of surviving a long journey and handling choppy water. Mrs. Ga saw me looking at a glossy photo of a prahu gliding over a coral reef. I told her casually that we might buy such a thing and explore the country on it. A petite woman with a sharp mind, she looked at me as though waiting for a wink. Cuddled in her arms, Gaku eyed me skeptically.

“Abunai desho.” Dangerous surely. Buy a prahu? What if it turns over and you lose all your belongings, your passports? What about wind blowing it onto the rocks? You could be severely hurt. Have you thought about currents between the islands? You’ll be carried out to sea. What about storms? The rainy season was due. And pirates? I had no answers to these questions and Jakarta wasn’t going to give me any.

My guidebook remarked on prahu in an entry on Pelabuhanratu, a seaside town a hundred kilometres south of Jakarta, “Pelabuhanratu town has little of interest, but the harbour is dotted with brightly painted prahu and the fish market is lively in the mornings.” After months of visiting temples and gazing at Buddhas, I liked the idea of going to a place that had “little of interest” and seeing these canoes. Though it would be out of the question to buy one there — Pelabuhanratu is on the south coast, exposed to the full force of the Indian Ocean.

We arrived in the town one evening and found ourselves in a buzzing cloud of motorbikes — ojek — manned by teenagers competing to give rides to passengers off the bus.

“Hey, Mister! Where you go? Hey! HEY! You want hotel?” I was reminded of stepping off the ferry at Tangier in Morocco. I was not in an especially good mood. I was feeling sick. The bus to the south coast had been smoke-filled and barely under control along the winding roads. I vaulted the ojek blocking the bus door, turned and lifted his rear wheel off the ground and swung him out of the way so Nadya could get off.

“HEY, MistAIR!” Rhyming with Fred Astaire.

Laut Kidul (Eastern Sea) guesthouse was three hundred metres from the market where the bus stopped. It was full of mosquitoes and welcomed guests with glasses of free tea and coffee, both black and heavily sugared. On the wall in the lobby was a large painting of a wild-haired woman in long, flowing green robes riding a bronze chariot drawn by a pair of stallions through the crest of a tumbling wave. Pelabuhanratu means “Harbour of the Queen.” The Queen, according to the guidebook, was a malevolent goddess who ruled the seas and took “fishers and swimmers off to her watery kingdom.” “Don’t wear green on the beach or in the water,” it said, “it’s her colour.”

We were up and out the following morning at eight o’clock, but by that time the fishermen’s day was over. The prahu had unloaded their catch into the market. Women in batik skirts and coloured headscarves upended net bags of lobster, sorted through piles of skipjack tuna, sliced open a small shark. Over the road, fifty empty prahu crowded into a small basin. Blue, white, red, orange and brown canoes snarled up in each other’s outriggers. Arini, Rawu, Melati, Bagja, Karya — their names, or the names of their owners, painted on the bows. Some had short masts with flags; some had vertical poles fore and aft supporting a horizontal pole — probably used to haul a fishing net over; all had “long tail” motors mounted on blocks of wood at the stern. We’d seen this kind of motor in Thailand, its propeller at the end of a two-metre-long shaft. The shaft could be swung in a wide arc, enabling the boat to make turns easily.

We walked onto the beach beyond. Big waves crashed down and disintegrated into seething foam that splayed over the sand and kissed the outriggers of more prahu. How did fishermen in these little boats get out to sea through that?

“Kami ingin pergi ke laut dalam prahu kecil.” We’d like to go to sea in a small prahu. “Ada kenal orang ikan?” Do you know a fisherman? We figured that an Indonesian fisherman would not know quite what to make of two bule (westerners) asking for a ride in his canoe, so we tried to get a lad called Yokay who hung around Laut Kidul to ask for us. Yokay was puzzled. Membeli? Buy? No. Mencoba. Try. Selama satu, dua jam. For an hour or two. The Indonesian language is not complex. No verb tenses to juggle, no tones like in Chinese, simple-sounding words, same word order as in English, roman lettering. Yokay went off. We didn’t see him again for two days.

Meanwhile, Nadya made an acquaintance on the street: Mr. Otong Hussain, English teacher at Nadi College. Would we like to attend one of his classes? Mr. Hussain’s evening class had five students: two primary school teachers and two boys and a girl from high school. The teacher put us on stools at the front of the classroom and quizzed us from the back on football, fast food, Hollywood and afternoon tea. The students nodded at our answers and said nothing. We asked the class whether they had any friends who were fishermen. They said no. They were afraid of the sea.

“Do you like mangoes?” said a girl in a timid voice after class. Yes, very much, we replied. She promised to bring us some from her garden.

“Tiga-puluh-ribu rupiah,” Yokay said with a wide grin: 30,000 rupiah, $9. We trailed him out to what appeared to be the most battered prahu on the beach, and he introduced us to a surly, blunt-faced man with a moustache who made us both feel uncomfortable and wouldn’t budge on his price.

“Never go to sea with a man who has a moustache,” I whispered to Nadya. We thanked him, thanked Yokay, said we’d think about it.

I wandered down the coast. I wanted to visit Asry Losmen (a losmen is a small guesthouse), where the owner, apparently, spoke English. I met an emaciated man who told me that a fisherman called Erry was the person to track down. Go early to the market. It was early on our fourth day in Pelabuhanratu, while we were on our way to the market, that I spotted a westerner. A red jeep stood outside a hardware store. Inside, a stocky man of about fifty in a T-shirt with a gecko on it was leaning on the counter. I went in. In fluent Indonesian, he was ordering things off the shelves. Tool parts, WD-40 lubricant, a wrench, copper wire. I waited to one side until he’d finished.

“When I came here ten years ago, there weren’t any warungs.” Leo Learoyd pointed at a row of bamboo huts on the beach as we gunned along the coast road in his jeep. “I helped the people build them.” An engineer by trade, Leo had come over from Brisbane on a bridgebuilding project and stayed. Built his own hotel, Pondok Kencana, ten kilometres from Pelabuhanratu.

“See that?” There was a yellow and brown prahu between two huts. “That’s just been built. They want a million roops for it. When did you say you wanted yours?”

Two days later, another prahu for sale was brought from Pelabuhanratu to the beach by a couple of fishermen, Ubad and Darso. It was red, blue and white, six metres long, had a sail, a rudder and two paddles. The sail, a piece of patched brown canvas wound around a bamboo pole, lay on the outriggers. Ubad had a flat, simian face and scrambled hair and looked as if he’d been at sea all night. Darso was shaved and in a collared shirt. I figured Darso was Ubad’s agent, but it was Darso who took me out in the prahu.

Pelabuhanratu is located in a large bay protected from the full thrust of the Indian Ocean by a fifty-six-kilometre headland. The ocean really begins beyond the point at Ujung Genting to the east. The waves near Pelabuhanratu, although surfable, are not so mighty that a canoe cannot be pushed out through them. If the timing is right. Holding the boat between them in a foot of water, bow pointing into the bay, the two fishermen looked out to sea. I stood at the stern ready to give a good shove when told. Leo and Nadya watched from the beach. There was a lull after a volley of big waves. Without saying a word to each other, the fishermen charged forward, pushing hard on the outrigger arms. Stumbling as the prahu got away from me, I dashed after them. Once the water was up to his waist, Darso jumped aboard and took up a paddle, began digging the water with clean, rapid strokes. I clambered up and did the same. Twenty-five strokes on my knees till we were clear of the surf.

“Ah, enak.” Darso stopped paddling. The word enak means delicious or tasty. I’d used it once or twice after the first three or four mouthfuls of nasi goreng, the national dish of fried rice, chicken and vegetables with prawn crackers on top. Darso put his paddle down and picked up the sail. It was about five metres tall. Resting it on his shoulder, he dropped the thicker end of the bamboo pole in a round hole in the middle of the boat. He unwound the canvas. The triangular sail was threaded to the mast with fishing line. A little bamboo boom, also attached to the mast with fishing line, flopped down. Darso angled the sail till it caught the wind. String served as a mainsheet. He wound the end of the string round the aft outrigger arm. We began to pick up speed.

“Ah, enak,” said Darso, laughing as if things had never worked out so well. We went out in the direction of Ujung Genting, tacked, came back. Darso took down the sail, picked up his paddle again.

“Lihat.” Watch. Facing backwards and using his paddle, braced against one of the outrigger arms, as an oar, Darso pumped the boat toward shore. After ten strokes, he said, “Enak,” and gestured that I should have a go. I looked at my paddle. It was a crude item, more a spade than a paddle. It had splintering bite marks in the end, as if it had been used to fend off a shark or a hungry dog. I took Darso’s place. It took me ten strokes to get the right amount of paddle in the water. Too much and I had to give such an enormous heave that it made my eyes bulge. Too little and the paddle scooped up the water and the prahu went nowhere. After twenty strokes, I’d succeeded in turning us full circle. Darso beamed at me. I knew what he wanted me to say. I sat down gasping for breath. No, that was not delicious. I’d be able to manage that method of propulsion for about two minutes.

Darso wittered away in Indonesian, no doubt offering other handy tips. I looked at him skeptically, nodding from time to time. If I could get this tree trunk in through the breakers . . . if we could even drag it down the beach to the water . . . would this rag sail be able to catch the wind for more than three consecutive days before ripping and collapsing? Would these . . . these spades, used as paddles or used as oars, get us along a thousand kilometres of coast, from island to island to island? I couldn’t believe that I was actually thinking of buying Mr. Darso’s vessel. No, NO! Come to your senses. When will you learn? We must travel along the waveless north coast in a boat that can actually be used as a canoe.

The next day, Darso and Ubad pushed Nadya and me in and we paddled with the spades like billy-oh till we were clear of the breakers. We sat panting in the blue water beyond and looking uncertainly at each other. Nadya had not been to sea before.

“Nadya, let’s get this sail thing up.” We staggered about trying to get the mast upright so it would slip into its anchoring hole. Waves slopped against the outriggers. Darso and Ubad watched from shore. A tweezer-tailed frigate bird looked down from above.

“Do you think we can get to land again?”

“Definitely,” I replied, also feeling in peril. I thought of the malevolent Queen of the Sea, checked to see that we weren’t wearing anything green.

“Let’s go up and down a bit.” I tried angling the sail the way Darso had. I must try to be authoritative on sailing, I thought — make Nadya feel as if she’s not risking her neck. We wobbled along unevenly, the sail filling and flopping. The rudder seemed unwilling to overcome the prahu’s inclination to go in a circle. It would take me days to realize that I couldn’t expect the same performance from a keelless wood canoe as I could from a fibreglass cruising sloop. After a short run, we swung the sail around and headed back to shore. This was awkward and involved paddling to aid the turn. Nadya’s paddling skills were more advanced than mine; she knew how to stir the water to turn the boat. After a couple of runs out and back, we began to feel more confident. One reassuring feature of the bay was the presence of fishing platforms, a score of them, bamboo and barrel structures which we figured we could grab onto if things got out of hand. We aimed for shore and, just out of the surf zone, wrestled down the sail and made ready with the paddles.

“You paddle on the left, me on the right,” Nadya advised. I was in the stern, she at the bow. We approached the white water tentatively. What would prevent a wave filling and sinking us, I wondered. From the sea, the breaking waves didn’t look anything like as intimidating as they did from shore. Keeping the boat pointing at the beach seemed to me critical. A ripening wave lifted and spun us.

“Keep ’er straight!” I called out. We realigned slowly. Then we were both sitting in a bathtub, soaked head to foot. “AH, MERDE!” Pushing wet hair from her eyes, Nadya turned round to look at me dumbfounded. I gasped for breath, shook my head, wiped water out of my eyes.

“Keep ’er straight,” I said again limply as the boat turned sideways to the waves. Another swamping. Then another. Grainy water swilled round our waists. I looked up, could see an audience on shore. People had come out of their warungs. Waves shunted the prahu to the beach. Nadya and I got out sopping and silent. Ubad and a couple of men helped us drag the boat up the sand. It weighed a ton. When we were clear of the water, Ubad pulled a small palm-bark plug at the stern and the seawater fountained out.

“Look at it this way. You didn’t sink. And now you know you won’t sink,” Leo said. We were back at Pondok Kencana drinking Bintang beer in a Jacuzzi with the Australian and Jelli, his fourteen-month-old baby. “It’s just a matter of timing.” We stared into the bubbles. “Count the waves. Seven big, then you get smalls. Go hell for leather when you see the smalls.” I wanted to ask him how on earth you counted them coming back to shore. Instead I raised some of Mrs. Ga’s concerns.

“Rainy season is late, Tony. Wind is in your favour. You’ll probably have to motor up to the headland. After that, you board the express east.” Now that sounded suspiciously like a Larry Roberts statement. “Pirates? There aren’t any. Not round here anyway. Besides, in fishermen’s clothes, you’ll blend in.” Jelli kicked her legs up and down in the Jacuzzi bubbles and giggled.

I bought Darso’s prahu: 1,700,000 rupiah (around $500), including two new sails, three paddles and a Japanese five-horsepower long-tail motor. Leo presided over the transaction, typing up a purchase agreement in Indonesian for us all to sign. Darso and Ubad seemed over the moon. We smiled uncertainly. Leo’s wife took a photo of us all. Our new purchase would reside on the beach, in the care of a handyman living in one of the warungs Leo had made.

The following three weeks went by rapidly. Nadya and I returned to Jakarta to get a social budaya (research visa). Having one would give us a half-year stay and save us the trouble of backtracking to Singapore every two months to get a new tourist stamp. But the Immigration Bureau required a respectable male Indonesian national to agree in writing to sponsor us. Once approved, we would then have to take our application to an Indonesian embassy outside the country and pay $30. Then the social budaya had to be “endorsed” monthly (with fees) to be valid. No. We would take a holiday to Singapore every two months. This peeved me a bit as it had taken me a day on Leo’s computer to type the research project outline, also required by Immigration: “Project: to travel through the Indonesian archipelago using a traditional fishing canoe (prahu kecil), possibly the most basic and culturally rooted example of Indonesian sea craft . . .” In Jakarta, we bought lifejackets, oilskins, DEET insect repellent, multivitamin pills, a map of Java and a compass.

While we were away, Pak Tata, the handyman, beefed up our prahu. It was all right as it was for fishing in the bay but too flimsy for a long journey with our packs, jerry cans of gasoline, provisions and whatnot on board. Especially given that it was not the gentle Java Sea we were dealing with. I drew him a picture of what I wanted done. Double bamboo outriggers on either side rather than singles, three outrigger arms rather than two, net racks between the arms to take our rucksacks, a new rudder, some kind of wooden cover over the middle of the boat, all leaks sealed, a fresh coat of paint.

“You know what tata means in French?” Nadya whispered to me when we got back. She was painting Monique, the name of her late mother, in black letters on the stern outside Pak Tata’s warung. I shook my head. “Stupid.”

We continued to stay at Laut Kidul in Pelabuhanratu, Leo’s classier hotel being too pricey for us. Each morning, we took a bemo or a pair of ojek to Pondok Kencana, picked up the motor (kept locked in a hut there), tied a red flag to the prop shaft, put it in the back of Leo’s jeep and drove down to the beach. We dragged Monique to the water empty. Once she was afloat, Nadya minded her while I got the motor and put it on its mount. The prop shaft, when out of the water, had a little wooden arm to rest on at the stern. I pulled the starter cord.

“How about now? Now seems good.” I stood at the stern, motor clattering at my side, propeller whirling in the air behind me.

“Wait!” Nadya was at the bow counting waves. On her command, we would charge forward into the sea until waist-deep, then jump aboard. I would drop the prop in the water and out we’d go. Sometimes we spent ten minutes in this position, eyes glued to the waves. Was that the last big one or was there another beyond it? Most of the time we got it wrong. Calm when we made our dash, but by the time we were aboard and picking up speed, big waves bearing down on us. WHOOSH! Bathtubbed, drenched, motor drowned and hissing, ignominiously rolled back to shore. We bought two plastic bailers from the market.

“Ombok besar. Ombok kecil.” Pak Tata explained patiently, drawing wave patterns in the sand for us. Big waves. Small waves. He was a docile man of forty-something. Six or seven big ones followed by a string of small. Just as Leo had said. Mr. Stupid was no dummy. He pointed at the first small wave with his finger.

“CEPAT!” Quick! He slapped the palm of his hand. Go hell for leather.

At the end of each day, Monique safely back on shore beyond the tide mark and tuc-tuc (Nadya’s name for the motor) in the jeep, Nadya and I played in the surf. We needed to work out the stress and try to make friends with the Queen.

It was mid-December. The rainy season would not hold off forever. It was time to buy supplies from the market. Gas, bottled water, lantern, matches, wok, tarpaulin for shelter, fishing lines, a large plastic bin for food, another for engine tools and spare parts, a third bin for books and maps. Rice, noodles, cans of sardines, salty crackers, peanuts. Fishermen’s clothes: thin, long-sleeved shirts, shorts, conical straw hats. Sacks made out of sail canvas to put our rucksacks in to keep them from getting wet. Gudang Garams, Indonesian cigarettes, to give to fishermen. We had also decided that, given our load, a little extra flotation might be a good idea: eight thirty-litre plastic jerry cans. Pak Tata strapped them to the side of the boat. He also found us bamboo rollers to help us get the boat into and out of the sea. We paid him 300,000 rupiah for all his work. He deserved twice that.

Leo officially launched Monique by pouring Bintang over the prow. We were enormously in his debt but had nothing to give him. I wasn’t sure why he’d helped us. Maybe it was a kind of engineering project for him to oversee. He’d discussed the modifications to the boat with Pak Tata. He’d gone over how to look after and service the motor with me.

On December 19, with the help of Leo, Pak Tata and several warungers, we loaded our in the shallows, pulled the cord on tuc-tuc, and at the first sign of a lull, went hell for leather out into the sea.