With the rain in my eyes, I can see a white light up ahead, stretched and dazzling. It appears and disappears behind tall black waves. The shore is a dark smudge to my left. I listen for the sound of breaking waves. Our little kerosene lantern flickers in the wind.

Four days from Pelabuhanratu. “We’re not going to be able to get to shore,” I said to Nadya at sundown. She stared at me. Now she sleeps, sprawled out in the middle of the boat under a yellow oilskin, with an orange lifejacket for a pillow. She really should be wearing that. I should be wearing mine, too. Instead, I’m sitting on it because my arse aches. I have been steering for seven hours. I stuff soggy nuts in my mouth and try not to nod off.

The light draws closer. I am dreaming of a harbour entrance. I know there is nothing of the sort there because the fishermen at Ujung Genting told us that it’d be a thirty-hour run to the next village, no break in the coral wall till then. A reef separates us from shore, green by day, causing the waves to explode upwards as they hit it.

The light marks a promontory of rock. Waves smack it. There is a wumpfing sound, then the chatter of showering water on the surface. I can see blooms of white foam.

The motor coughs. Nadya is awake as if she’d never been asleep. We are used to the sound. Every three hours, tuc-tuc needs fuel. The motor dies. We are left with the sound of water bursting over reef. Controlled panic. Prop shaft up (to make the fuel tank level), gas can out, unscrew cap on fuel tank, insert funnel. She pours. Cap back on. I pull cord. Nothing.

“S’il te plaît, tuc-tuc, vas-y,” she implores. I pull again.

Apart from the reef, there were two surprises waiting for us beyond the headland at Ujung Genting. No express east — wind instead in our teeth. That meant no sailing. And no more fishing platforms. We had spent our first night happily tied to a fishing platform, sleeping on the nets Pak Tata had strung between the outrigger arms. I was hoping to repeat the experience here and there when the waves hitting the beach looked malevolent.

But it was the coral reef that really got my goat. First break in the wall thirty hours away? The fishermen at Ujung Genting had prahu like ours, same little motors. Thirty hours, they had said. I didn’t know how fast we were travelling, but if that were true, then it must be a good hundred kilometres. How come no one in Pelabuhanratu had mentioned the reef? Did the fishermen never venture out of the bay? Not that we’d asked anyone what was beyond the point. Hadn’t Leo known? He’d been living there ten years.

With night and the start of the rain, I felt afraid. This no-flying round-the-earth lark had thrown me one or two curve balls, but this one caught me on the chin. What would happen if a wave seized us now? Flung us on the reef in darkness? Was a storm brewing like the one Tebrinda had run into? There was no one aboard with the expertise to come up with practical solutions. Not that there was much to do but stay away from the crashing surf. “Only the land can hurt you,” I recalled a yachtie saying on Ascension Island about the Atlantic. Then again, was it possible that we might be swept out to sea if I didn’t track the coast?

I spent the night looking down at the compass, illuminated by the lantern, and up at the land, straining my eyes to make out the contours of the coast. A course of east-sou’-east, I thought, to allow for the push of the waves towards shore. The wind came in spattering gusts, but I was not really in discomfort. My new oilskin was keeping me reasonably dry, and the conical hat worked beautifully. The ride was rough, but I noticed that the outriggers offered a first line of defence against the waves. Little water slopped into the boat. Every half hour or so, I bailed. Seasickness did not trouble me, maybe because of the size of the boat, or maybe because I had plenty to think about.

In the early hours of the morning, the rain eased up and then stopped. I sat back, nodded off. Nadya was my alarm. When the sound of surf was too loud, she shouted at me. At dawn, after we topped up the gas, she took over steering. She looked haggard but determined. Perhaps she wished she were back in Montreal, putting presents under her Christmas tree.

She shook me at nine. A mist lay on the water. She pointed ahead: a curl of smoke, and on the water between it and us, pencils of wood. Prahu. I saw the relief on Nadya’s face and felt the same. There must be a gap in the reef.

“CIDAUN?” I yelled as we approached the nearest prahu. Two men nodded, pointed at the shore. I took over the helm. Going towards shore was like climbing down a staircase, down a level with each passing minute. I looked over my shoulder but did not see a hill of water behind us. The reef approached. I braced myself for a hard time getting in through the surf, but there was nothing to worry about. The entrance was clear, like passing through a gate. Water beat at the coral walls to either side; a choppy, virtually frothless passage lay between. We glided into a rocky bay without taking a drop on board.

“Dari mana?” “Ke mana?” “Berapa jam dari Ujung Genting?” Eight fishermen dressed like us helped drag our boat up onto the pebble beach. Other prahu with scratched hulls perched like bizarre insects on ledges of rock. Where did you come from? Where are you going? How many hours did it take you from Ujung Genting?

“Dua . . . puluh . . . tiga jam.” Words were difficult to come by. Both of us were groggy; our voyage had taken us twenty-three hours. A woman shooed the inquisitive fishermen away and led us up a mud cliff to a warung, put bowls of indomie (noodle and egg soup) in our hands. “Terima kasih,” we said, yawning. Thank you. As we ate, I saw that our belongings had followed us. Fishermen were stacking them in the corner. Plastic bins, gas cans, lifejackets, rudder. The oldest, a man with a grizzled head, stopped, stooped, hands on his knees, and looked us over.

“Berani!” I thought the word meant crazy. I nodded dopily. Later, I found out it meant brave. When we were done eating, we followed the woman like obedient children to her losmen and slept for ten hours.

Christmas lunch at Pelabuhan Jayanti, port for the town of Cidaun, was skipjack tuna on rice, followed by doughnut rings, banana fritters and mango. Not that any of the Jayantians were celebrating. After lunch, Nadya went for a swim at a beach to the side of the bay where we’d come in and attracted an audience of twenty men, me among them. It was not so much a swim as a bout of wrestling. Big waves barrelled over the reef and struck the beach at angles. They knocked Nadya off her feet, rolled her head over heels, lifted her, pressed her down, tossed her out finally on the beach. Thank God we hadn’t been carried in on a wave during the night. The violence of these waves made me wonder if it was safe to continue. How much further did the reef stretch? Not all the way to the end of Java, surely? I tried to find out from the men, but either they had no idea or they didn’t understand the question. From our map, I could see that the Javan coastline curled north and formed a bay a hundred and sixty kilometres east of Cidaun. It was not unlike the one we’d set out from. I could not expect a change before then.

We settled our warung and losmen bills, stocked up on bensine (gasoline), gathered from the men that there were more stops like Pelabuhan Jayanti along the way.

Our two months were up. After Christmas, we did a visa run to Singapore. Bus to Bandung, bus to Jakarta, twenty-nine-hour ferry to Bintan Island, hydrofoil to Singapore. We left Monique with a fisherman called Ade who lived in a warung on the beach at Pameungpeuk, a village just east of Pelabuhan Jayanti. We promised to pay him menjaga (for babysitting) on our return. We were gone almost two weeks.

On our second day back at sea, the waves seized Monique and flung her on the reef. It was two o’clock in the afternoon on January 14, a sunny day with a brisk easterly wind. We’d been battling the wind for seven and a half hours. It was a relief to see a neat row of empty prahu on the beach: Cipatujah, the next little haven. We turned and headed towards them. The sea was doing battle with the reef in front of us. Scary wumpfing sounds, plumes of spray shooting skyward with each impact. But it was just a matter of finding the gap. We buzzed back and forth, hunting, ours the only boat on the sea.

Nadya spotted a man walking along the beach in front of the prahu. I circled the boat in as close as I dared and she screamed “MASUK DI MANA?” at him. Where’s the entrance? He pointed. We looked. White water. I nudged closer. Monique began to buck and rock. We held up our hands, baffled. The man pointed again. White water. Another man joined him. The second man made a kind of zigzag gesture with his arm.

“What do you think?” Nadya stood up before answering.

“I think . . . maybe . . . over there.” We put our lifejackets on, checked to see that the lids on the plastic bins were tight under the wooden cover and made sure there was nothing loose in the boat. I put a plastic bailer between my knees, Nadya picked up a paddle. Now a group of men on shore was watching us.

“I will tell you which way to go, okay?” Nadya said. We entered a patch of confused water. Small waves sloshed over the outriggers, rocked and slapped Monique’s hull. I went slowly, one hand on the rudder arm, the other on the prop shaft. We were now at the reef. Now, it seemed, passing through it. I began to see that what was around us was fall-out from the explosions to left and right. And yet there was still coral in front of us, water mounting it, spray flying.

“Left. Go LEFT!” I turned the rudder, helped it by swinging out the prop shaft. Nadya paddled to assist. Water broke in over the side. I bailed it out. Now the way ahead was clear, a diagonal course. Very soon, the opening to the beach would reveal itself and we would wash up and join the other prahu. It was a pretty beach, bright golden sand, palm trees shading the boats. Another wave slopped in. I bailed.

“Tony, where . . . ? I don’t see . . .” The beached prahu were on sand beyond a table of green-brown coral. Little wonder there were no boats on the water. It was low tide. Wrong time of day to get in or out. I looked back over my shoulder. Too late to beat a retreat. Waves were rolling us in. I cut the motor, lifted the prop out before it scraped on the bottom, grabbed a paddle, readied myself for the sound of splitting wood.

“Try and stay with the boat!” It was the only thing I could think of to say. A wave lifted Monique and pitched her onto the reef. She banged twice making us jump in our seats, then, with an ugly scraping sound, twisted and slid. Just as long as she didn’t flip. A second wave came in at more of an angle lifting the starboard side. We leaned over to compensate. A third carried her further in. More sliding and scraping. We stabbed the coral with our paddles trying to brake. A fourth put us in two inches of water.

“Tony, you have your shoes on?” I looked over the side. The coral was brown and dead. Some of it was carpeted in seaweed. I put my flip-flops on. Another wave washed the boat a little further, spun it round. We jumped out, threw our weight behind the outrigger arms. Lifting the loaded boat clear of the reef was not possible.

“Try to get it onto the seaweed with the next wave,” I said and joined Nadya at the front. Maybe the boat would slide on the seaweed. Outrigger arms in the crooks of our elbows, we heaved together, one on either side. Made a few feet, tried again, a few more.

“It’s no good. We have to unload. Maybe we’ll do damage if . . .” Nadya gasped.

“Er . . . yeah . . . s’pose so. Maybe the bamboo rollers . . .” The Cipatujahns intervened. Sixteen shoulders lifted Monique clean off the reef and ran with her to the beach. We gawped at each other, gave chase. I lost one of my flip-flops in the water and then burned the sole of my foot as I stepped onto the hot sand. The men dropped the boat next to the other prahu and cheered. We laughed in relief, went round shaking hands with them all. They were a motley crew in greasy sweatshirts and frayed shorts, some in T-shirts with fish-blood smears, two in ragged sarongs, all sinewy and charred bronze by the tropical sun. I dug in a plastic bin for Gudang Garams, passed them round. A paltry way of expressing gratitude, but, as I had discovered in Africa, there was really no satisfactory way of repaying people who helped me out.

I walked over to Monique and pulled the bark plug. Water ran out. I looked inside, expecting to find a section of the hull caved in. Nothing. I inspected the outside. There was a dent at the front, some of the paint gone and some long scratches along the sides, but I had seen worse on the prahu at Pelabuhan Jayanti.

“Dari mana?” “Ke mana?” “Berapa jam dari Pameungpeuk?” Where from? Where to? How many hours from Pameungpeuk? The fishermen went through our gear, opened one of the plastic bins and had a look inside, picked up a lifejacket, tried it on, shook the compass.

“Ini ikan?” one of them said, slapping a rucksack. This fish?

“Tidak. Barang.” No. Belongings. He looked puzzled. He asked something neither of us understood. Something like: so, if you haven’t been out fishing, what are you up to?

“Jalan-jalan,” Nadya said. We would use the phrase a lot to explain ourselves. Travelling for pleasure.

“Oh, jalan-jalan?” The group broke into laughter, shook their heads, led us up to a warung. Travelling along the south Javan coast for pleasure. The idea of it. Talk about provoking the Queen of the Sea.

All we saw of Cipatujah was the lone warung where we ate. Rice with a grey fish I didn’t recognize, chopped chili in soy sauce alongside. Same for dinner. But Cipatujah came to see us. We sat leaning against our belongings and snoozed through the afternoon. Once the fishermen had had their fill of squatting and staring at us, it was the housewives’ turn. They brought children and babies. The housewives were relieved by the elderly. Look what washed up on our beach.

We left at dawn with the fishermen. Not as tricky as arriving, but no cakewalk either. High tide did not do much to cover the bit of the reef we’d caught on the day before. We had to push and drag Monique before we had enough water to drop the prop in. Then, when we had carefully negotiated the diagonal channel — Nadya fending off coral heads with a paddle — a wave came over the reef to our right and clobbered tuc-tuc. For a second, we were speechless. Tuc-tuc hissed angrily. Monique began to slip backwards, sucked back down the channel.

“SHIT! Paddle for it! Go! Go! GO!” we screamed at each other. The other prahu, I noticed, were made of fibreglass and had Yamaha out-boards. They could zip away. This little breach in the reef was not made for prahu like ours. We drove our paddles into the water, pulled back hard. Dug, pulled. Dug, pulled. Counting out each stroke till we were in the clear. Then sat panting, watching the other canoes disperse.

“Nothing . . . like a bit of exercise . . . before breakfast.”

“Just start tuc-tuc, Tony.”

At the end of the day, we joggled through rough water surrounding a jagged headland and turned north into Penanjung Bay. An hour later, we slid effortlessly onto a coral-less beach licked by ten-centimetre waves and crowded with prahu like ours. Our first battle with the Indian Ocean was over.

We’d heard there was a losmen at Batu Karas, and it turned out to be a short walk from where we landed. Exhausted, we unloaded, looking forward to a night in a bed after two sleeping rough. Returning to the boat after taking two plastic bins inside, I found Nadya with tuc-tuc on her shoulder.

“Wha . . . what are you doing?” I considered it my job to carry the motor to and from Monique. It was the weight of a sewing machine, had to be jerked onto the shoulder and had a tendency to leak oil down my neck. Nadya stood on the beach, tuc-tuc’s tail sloping down her back, a look of determination on her face that I’d seen on our first night at sea. One morning, back when we were training, she had confided after our third swamping that she didn’t know whether she could go through with this project. But she’d survived a harrowing night at sea, several hairy entries and exits through coral reef and now was carrying our motor like a fisherman.

We stayed three nights at Batu Karas and then, feeling relaxed about prahu-ing for the first time since starting out, crossed the quiet bay to a peninsula on the far side called Pangandaran. At the end of the peninsula, there was a woodland nature reserve with five-metre-high viewing platforms scattered through it. I wished for binoculars. Flying foxes or perhaps flying lemurs glided between the trees, hooking themselves to the trunks with long claws, furry skin wings stretched between front legs and back. Chestnut and silver monkeys shook the branches. Black and white hornbills flew in pairs and threes overhead, their beating wings making an odd reedy sound. At sunset, black fruit bats the size of domestic cats, hundreds of them, flew from the reserve west along the shoreline to feed inland. After a meal of ikan goreng (fried fish) and rice, we walked along the beach, craning our necks, watching the bats. They flew low and slowly and looked sinister against the red sky.

“Hate to say it, Noo.” I had given my travel buddy a nickname. “Think we’re gonna have to spend another night at sea.” It was January 23, a warm evening with a light breeze from the east. There were no boats in sight. I was surprised that the rainy season still hadn’t kicked in. We were supposed to be in the middle of it. Nadya shrugged.

“Do we have enough bensine?”

“Barely.”

“We’d better eat before it gets dark.” She opened the plastic bin containing our food, brought out crackers, sardines and dates.

At times, it didn’t seem as if there was still a coral reef to our left. Since leaving the shelter of Penanjung Bay, there was certainly less of it. Sometimes we ventured close, then saw the green shelf through the waves. It might have been possible to ride up over it in places, but we couldn’t take the risk without anyone around to lend us a hand if we got stuck. We’d been keeping an eye out for a river mouth to hide in. Fishermen at our last stop, Pantai Ayah, had mentioned it.

This time we did shifts through the night. Three hours on, three hours off. Couldn’t get the lantern to remain lit, so we had to feel our way along the coast without the help of the compass. There was one panicky moment when tuc-tuc died and we were almost in the surf. Out with the spades. Otherwise, the night passed peacefully. On her watch, Nadya sang songs in French. I jogged my favourite English country lanes and went to bed again with my old girlfriends.

When I woke, the reef had gone, replaced by brown cliffs, fifteen metres high, decorated with hanging foliage, undercut at the base. The Indian Ocean punched it and rebounded spectacularly, making echoey, slurping sounds where it penetrated. I shuddered. The water was calm twenty metres out, just the swell lifting and dropping the boat. If tuc-tuc kept tuc-tuccing, we’d be fine. How utterly we were relying on him. The day was still. There’d be no sailing. If tuc-tuc gave out, we’d have to paddle to Baron, our next haven. I remembered how that was with Darso. The motor coughed. We put the last of the gas in the tank. Three hours at most.

Two hours and ten minutes later, a break in the cliff. Sighing with relief, I steered in. We could hear shrieking coming from a small beach. Baron appeared to be inhabited by kids. Once one had spotted us, the word that something strange was about to wash up spread like wildfire. Twenty of them raced in and out of the shallows, pointing. By the time we hit the sand, a dozen six-, eight-, ten-year-olds, their bodies skinny, molasses coloured, shiny and bare, had climbed on our outriggers and were jigging up and down shrieking “Mistair! Mistair!” The racket drew the attention of older brothers and sisters, teenagers in shorts and T-shirts, who drifted over and leaned or sat on the boat and smoked. Monique disappeared under bodies. I wondered if this might be more detrimental to her health than hitting coral or cliff.

“Dari mana?” “Ke mana?” “Berapa jam . . . ?”

This was Renean, not Baron. Baron was in a sheltered cove twenty minutes further on. There was no bensine here. We spent a night flaked out on the sand, shoved off early the next morning. As we approached Baron, we tipped our cone hats over our eyes. Monique rode up on the sand. No tot invasion; our arrival went almost unnoticed for a change. As we unpacked, two fishermen from a fibreglass prahu and a band of curious wives came by, asked the usual questions but didn’t freak out. Baron was not far from Yogyakarta, and “Yogya” (pronounced Jog-ja) was probably the biggest tourist magnet on Java. Baron had a guesthouse with an English-speaking owner. Shouldering tuc-tuc, I gave him a shake. An eggcup of gasoline was left in the fuel tank.

It was Idul Fitri in Yogyakarta, the Muslim celebration marking the end of Ramadan. The city was a hive of activity. Motorbikes, bemo and bekak (three-wheel bicycle taxis) flew up and down Jalan Malioboro, the main street. Souvenir stands shaded by giant red parasols sold laughing Buddhas, masks, Javanese puppets and clay representations of the ancient temples Borobudur and Prambanan. The sidewalks were crowded with shoppers sorting through racks of batik dresses, sarongs, shorts, shirts and selendang (shawls); Pasar Beringharjo, the indoor market, was packed with more sifters through batik fans, purses, wallets and clothes.

Yogya is the batik capital of Indonesia. Asking a youth the way to the Kraton, the Sultan’s Palace, we found ourselves in a batik school down a back street. Around the walls were big sheets of material bearing interlocking geometric patterns and images of brightly coloured fish, flowers, trees, birds and serpents. A woman sitting on a chair applied blobs of hot liquid wax with a wooden pen to a flower head on a cotton sheet draped from a wooden frame onto her lap. As beautiful as everything was, we had no room on our little boat, and so, alas, we could buy nothing.

A troupe of musicians played gamelan xylophones, tom-toms and kenong, brass “kettles” sounded with a mallet, at the white-pillared, red-roofed entrance to the Kraton. In the square outside, the Sultan’s guards paraded up and down, beating snare drums, blowing flutes and thumping gongs. Their costumes were extravagant: black stockings, white tunics, gold-embroidered jackets, wide-peaked box hats, and red cummerbunds binding kris, traditional daggers with wavy blades, to their waists. There were balloons and picnicking families and people straddling motorbikes looking on. And a rooster, his cock-a-doodle-doo added to the mix of sounds. What was a rooster doing amongst all these onlookers? I decided to track it down. It belonged to a man with a ponytail and a cardboard box of whistles. Cost you 1,500 rupiah if you wanted to sound like a rooster. Wishing to vent some of the tension from prahuing along a prahu-unfriendly coast, I dug some roops out of my pocket and bought one. Nadya did not want to sound like a rooster.

Before Islam took over at the end of the sixteenth century, Buddhism and Hinduism were the dominant religions in Indonesia, with Buddhist Srivijaya centred in Sumatra and Hindu Mataram in Java. Near Yogya were the ninth-century relics of Borobudur, the Buddhist temple, and Prambanan, the Hindu temple complex.

Borobudur, a product of the Syailendra Dynasty, took peasants almost a hundred years to construct, dragging over two million blocks of stone from the nearby Progo River with horses and elephants. Borobudur is the largest ancient monument in the southern hemisphere and the largest stupa in the world, with its six square levels, representing earth, and then its three circular levels, representing heaven. Climbing Borobudur took us from relief carvings of Siddhartha’s earthly existence, up into the company of hundreds of seated and serene Buddhas peeking from rows of niches, and up again to Nirvana — bell-like stupas containing more Buddhas. To attain enlightenment, serious pilgrims circle the temple nine times (a distance of 4.8 kilometres) while ascending. As it was a rainy day, we cheated, sampling each storey from the central staircase.

Prambanan, built by Hindu Javanese kings shortly after Borobudur, probably with the intent of outdoing it, is the most extensive Hindu ruin in Indonesia, although only a handful of its original two hundred and forty-four candi (temples) still stand. We saw eight pointed grey towers resembling rockets ready for take-off. The three tallest were devoted to the Hindu gods Shiva, Brahma and Vishnu. Carved stone reliefs of incredible intricacy stood out from the walls, the images mythological and bizarre: large-breasted female dancers in flower headdresses, multiple necklaces and strings of beads coiling around their upper arms; wide-eyed demons with broad, toothy grins, tongues lolling out; hovering human-headed birds; monkeys in headdresses picking fruit from trees.

Nadya and I both enjoyed the easy tourism, the rush of sights and sounds, taking pictures, merging with the life on the streets. We felt we’d earned it. Yogya was also a chance to eat well: satays, ayam goreng — marinated fried chicken — and gado gado, cubes of tofu, sliced carrot, slices of boiled egg, chopped green beans and bamboo shoots in a peanut and garlic sauce.

Revived, we returned to Baron and the canoe.

February 20, 1998

“HE-E-E-E-ELP!” Nadya jumps up and down on the boat, trying to hail another prahu kecil on the horizon. It is returning to the coast after a night’s fishing.

“Hey! HEY! HEY!” She waves her straw hat frantically. I sit and watch her. The prahu is much too far away for the fisherman to hear her. We can’t even hear its engine.

Sitting is pleasant while we are still in the shadow of Nusabarung Island and the water is smooth. There’s no point in going back to the island. We have just spent a night there on a deserted beach of coral shrapnel. There isn’t a breath of wind, so sailing’s not an option. The early morning sun makes the sea glimmer.

The coast of Java is in haze about fifteen kilometres away. I feel thankful that tuc-tuc didn’t quit yesterday. At times, we were twenty-five kilometres off shore. Just us out there, and dolphins chasing schools of tuna.

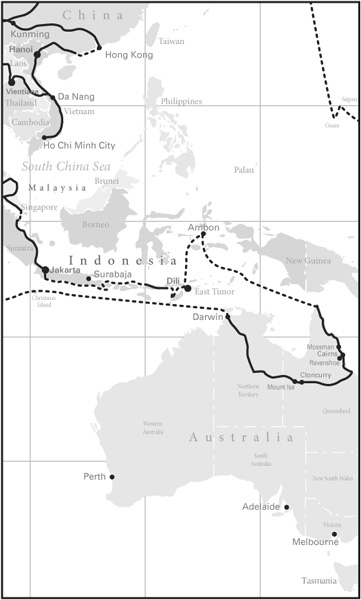

Two months had passed since we left Pelabuhanratu. Monique was seven hundred kilometres east of Leo Learoyd’s hotel. I was heading in the wrong direction for England but the right direction for Australia.

We were now in eastern Java, and the coast had become jagged and bitty. The coral reef was still there, but promontories and peninsulas and turrets of rock now broke it up and gave us coves to hide in when evening came. Like the fishermen, we were living with the sunlight. Up and onto the water at dawn, tucked into a nook an hour before dusk. We got more ambitious. Instead of hugging the shoreline, we took compass bearings from peninsula to peninsula and skipped all the crinkles in between. Instead of two hundred metres from the beach, we went out five kilometres, ten kilometres, fifteen.

Tuc-tuc was sick. Yesterday, he did a ten-and-a-half-hour, forty-eight-kilometre day across a huge bay south of Lumajang to the island of Nusabarung. At the end, within easy paddling distance of the island, he conked out. We had re-juiced him half an hour before. Maybe he’d overheated. Today, after twenty minutes, he’d cut out again. Then again. And again. We examined him closely, gave him a thorough wipe, unscrewed parts and cleaned behind them, tried with our scant knowledge of engines to figure out what was wrong. I squirted oil about liberally. Nadya spoke to him soothingly in French. After many drenches, he probably had salt in his pipes.

The thing to do was paddle. Not the full sixteen kilometres to Puger, the nearest port, but to the path the returning prahu were taking. Ask for a tow. And we had to do it right away. The fishermen would soon be off the water for the day, and we were short on drinking water. Still no sign of the rainy season. Not a cloud in the sky. It was going to be another sweltering day.

I tried Darso’s spade-against-outrigger-arm rowing technique, but I just wasn’t Darso. The paddle kept slipping and my travel companion wasn’t interested in drawing circles.

“MISTAAAAAAAAAAIR!” Noo was really full of beans this morning, waving her hat over her head. We had paddled about a kilometre closer to Puger. We could now hear a motor. It hiccupped. A fisherman had spotted us.

“How about a tow?” I said it in English because we didn’t know the words in Indonesian. Nadya held up a rope. “Mesin mati,” I added. Our motor’s had it. The fisherman was in his thirties, had a flat Chinese face with a thin moustache and wore a salt-stained green sweatshirt and a kind of straw bowler hat with a green brim. His prahu was painted light blue and green. This man clearly did not believe in the Queen of the Sea.

“Berapa?” he inquired. How much? But the way he said it, it sounded more like: so, what’s it worth to me? I had no idea what the going rate was for tows to shore.

“Lima-ribu,” Nadya said. Five thousand. He scrunched up his face in pain as if she’d just punched him in the stomach.

“Puger, JOW!” It’s a long way to Puger.

“Tujuh-ribu.” Seven thousand. He leaned back. He was beginning to enjoy himself.

“Dua-puluh,” he decided. Twenty thousand. Nadya snorted. I thought she might get her Chinese weighing scales out to prove to this man that she wasn’t to be trifled with. Five minutes later, she had risen to sepuluhribu (ten thousand) and refused to budge. I felt like reminding her that this was not the market. Ten thousand was a little under three American dollars.

The tow began. Ended after two minutes. The fisherman’s tuc-tuc was the same size as ours and just didn’t have the umpf to do the job. The man unhooked, stood up and began waving his hat silently. Another prahu buzzed over.

“Berapa?” Negotiations started afresh.

With two prahu towing, it took us an hour to reach Puger. An hour including the pause midway so that Mr. and Mrs. Bule could top up the towing vessels with bensine.

Puger was a large port by south coast standards. It was here that Monique met her big brothers, prahu besar: ornate, fifteen-metre tuna trawlers with fancy prows looking like half-submerged boomerangs and red and blue helmsman’s cabins elevated on stilts. Rather than tuc-tuccing, these boats went dakka-dakka-dakka and sent wedges of black smoke into the air.

We rode up on a mud bank that reeked of rotting fish. I tucked my shoes into my pants, shouldered tuc-tuc and plodded through thirty metres of goop before finding firmer ground. While the patient was having his carburetor cleaned in a hut, I bought a plump tongkol (skipjack tuna) from the market for 2,000 rupiah. We ate it that evening, skewered on a stick over a beach fire in the harbour entrance while listening to prahu besar chugging out to sea.

On our map of Java, there was a circle around Grajagan. Beside, Nadya had written the words “NO. Bad waves.” The bay in front was a world-class surfing spot. An Australian pal of Leo’s staying at Pondok Kencana had warned us about the place; his fifteen-metre fishing boat had run aground trying to get into the harbour. But Grajagan was the last place to stock up on supplies before rounding Blambangan; there was nowhere else nearby. The eastern most extreme of Java is a large peninsula sticking out from the land like a swollen thumb. It is a national park, and boats aren’t supposed to stop there. The next port was a hundred and twenty-eight kilometres away in the Bali Strait.

We sat, engine idling, prop out of the water, four hundred metres from shore. I was at the helm. The entrance to Grajagan harbour was plain to see: two wrecks beached on sand at one side, rocks and cliff on the other. Big waves toppled and disintegrated in front of them, shattering over the rocks. Also obvious was a quiet little beach to our left with seven prahu kecil sitting on it.

“Maybe we can go in the harbour, maybe not. Let’s go to the beach and ask,” suggested my partner sensibly. “We can probably find out about Blambangan there.” A prahu half as long again as Monique clattered past and without hesitation speared into the harbour.

I looked at Noo, said nothing. We had had a row the night before. Pelabuhan Lampon in Rajekwesi Bay, about thirty-two kilometres west of Grajagan, had been the destination. As light faded, there was no sign of it. We were in the bay and I was steering. Noo was shouting at me to make for the nearest beach. But I wanted a mandi and a hot warung meal after four nights of sea washes and instant noodles on driftwood fires. We found Lampon tucked down the side of a tooth of land in the nick of time. We got a fresh-water wash and a plate of nasi goreng.

“You always do exactly as you wish,” Noo had complained. As I did most of the steering, it was true that I was choosing the nightspots.

I looked at Grajagan as though it were snubbing me. “Nah, the town’s going to be the place for supplies and information, and if that prahu can make it in, so can we.” I threw the revs to max on tuc-tuc, dropped the propeller in the sea and aimed Monique’s prow at the harbour mouth.

“Oh, merde.” Nadya zipped up her lifejacket, grabbed a paddle and huddled down. At three hundred metres, a big wave rolled under the stern and lifted us. I got a view of the fishing trawlers in the harbour. The wave tumbled just ahead of us, tossing up spray. Thirty or forty seconds passed. Tuc-tuc hammered away feverishly, shaking on his mount. A bigger wave caught up with us, trundled under the boat and seized her.

“HOLD ON!” Leaning back, propeller out of the water, we began to surf in to shore fast. Monique was suddenly in line with the wrecks, one a yellow and red prahu besar leaning on its side. The wave tipped and crumbled around us but didn’t swamp the boat, seeming to break gradually, lowering us gently as it did so. We shuffled along in churning foam, taking on some water. Nadya bailed. Another wave pushed us further. Then we were through the bottleneck and in choppy water. There was a sand-spit in front of us. I veered left. Waves butted the side. The water got quieter and I eased the throttle back. The channel twisted away to the right and the harbour opened in front of us, a row of trawlers like at Puger and fifty smaller prahu dotted about on mudflats. Monique, I observed, would be the smallest vessel at Grajagan. I lifted the prop, killed the motor. We slid to a halt.

“I’ll go see what’s about.” Nadya nodded silently as I jumped out.

I learned that the only losmen was not in Grajagan but on the beach we had passed coming in. The owner there would have any information we might need about Blambangan.

“I TOLD you we should stop at the little beach!” Noo was furious. “I told you.”

“Should have stopped,” I said.

“COCHON!” A paddle came flying through the air at me.

By the time I had bought bensine and Nadya had gone shopping for supplies, it was mid-afternoon. Monique was the sole boat trying to leave the harbour. We had everything we needed to take on Blambangan. Three jerry cans of gas, two bags of bread rolls, a large bunch of bananas, more tinned sardines, oranges and six two-litre bottles of drinking water. After a good night’s sleep, we would round the cape and be free of the coral reef.

Passing back through the harbour mouth, we were surprised to see that the two wrecks had disappeared. A couple of men were picking up scraps of wood. Monique bumped over criss-crossing waves, ploughed laboriously through patches of froth. We waved at the men. They stared at us. I looked out to sea. A bank of white water was approaching. I swung right and mounted it at an angle. Foam washed over the port outrigger. Monique dipped into the trough beyond. I swung left over the next one.

“That’s the way to do it!” Nadya said nothing. She pointed.

Next was a wave that hadn’t yet broken. I watched it advance towards us. It seemed to be taking forever to topple. It stumbled forward precariously, spilling water from its crest. Okay, now it was going to break. No. It leaned back as though pulling itself together, crest wobbling. Then tipped forward again, small sections of the crest peeling off into crescents of foam that were quickly absorbed into the body. I was mesmerized. The wave was about three metres tall and now practically vertical. In about ten seconds, it would hit us. There was no way we would be able to scale such a face. And beyond it, there was another one. Beyond that, another. It was then that I understood what the danger was at Grajagan. These waves were no larger than the big ones in front of Pak Tata’s place, but in a prahu kecil, you couldn’t count them off and then race to sea in the lull that followed. The surf zone was too long.

“Oh, God. LEAN FORWARD!” I steered straight at the wave, afraid that we might flip if I tried to broach it. Maybe we would slice right through, shoot airborne out the other side. WHOOOOOOOSH! I heard a scream up front. With a roar of falling water, the wave broke on our heads, drenching us, filling Monique, killing tuc-tuc.

For a moment, Nadya and I sat stunned and dripping, listening to the motor snarl. I blinked, blew the salt water from my lips, wiped my face. I looked down. The boat was three-quarters full of water, swirling round our belongings. I looked up. Knew what I had to do. I had thirty or forty seconds. Snatching up a bailer bobbing next to a bag of sodden bread rolls, I slipped over the side of the boat and, holding onto the stern, began bailing briskly. If I could get rid of most of the water, then. . .

It was not easy. I had to lift myself out of the water with each scoop. Nadya turned round to watch. After twenty scoops, the next wave arrived and topped the boat up. I clung to the side with both hands, closed my eyes, held my breath as it washed over my head. I surfaced, bailed faster. Nadya waited for me to come to my senses. Another wave rolled over us, filling Monique to the brim.

“Tony. TONY! It’s no good. We have to paddle.” I stopped bailing, stared at her stupidly. Caught my breath, nodded. I tossed the bailer in the boat, heaved myself up. Nothing was tied down. Our belongings were abandoning ship: a gas can with an air-bubble in it, several oranges in different directions, a foam sleeping mat unravelling itself, my flip-flops, two shopping bags of groceries spilling their contents. Nadya was scrambling about trying to save things, paddle and tarpaulin under one arm, the bunch of bananas in her hand.

“Tony, the other paddle!” I leapt onto one of the outrigger arms to retrieve it.

We sat on the outrigger arms and tried to shunt Monique in the direction of the beach. Weighed down with water, she was unresponsive. The situation was out of our hands. Either the Queen of the Sea was going to throw us on the rocks for our impertinence or she would have mercy and let us ride up on the beach where the wrecks had been. Wave after wave rolled over us, clapping me on the back.

I had been warned not to enter Grajagan back at Leo’s. I had seen the right place for boats the size of Monique at the side of the harbour. My travel companion and lover had told me what was best to do. Why had I been bull-headed? What was I trying to prove? Wasn’t it enough to travel along a rough coast in a primitive canoe without taking foolish risks? Stubborn Taurus had put us in jeopardy. But that was an easy excuse. As I got further and further round this earth, something inside me wanted more and more and more from these land and sea experiences. Air travel was soft, indulgent, false, passive — the lazy man’s option. I was determined to make surface travel the exact opposite. Hard. Gritty. And each experience had to outdo the last. Hours at the roadside hitchhiking when I could have taken a bus. All the way across Canada on a bicycle, refusing to accept a lift when spokes broke. Over the Pacific Ocean on a small yacht at the wrong time of year instead of joining the flotilla. Hard class on every Chinese train. Something in the back of my mind said that pushing to the limit would yield the full experience. As if there were a certificate of achievement waiting for me at the end of each leg, a hero’s welcome back in England.

It was one thing to stick my neck out while travelling alone, quite another when sharing the journey. I looked at Nadya, bedraggled, exhausted, anxiety written over her face, using her very considerable paddling skill to save us. She had shown such courage and resilience through two and a half months of soakings and worry about whether we’d be dashed on coral. Living with the sea was easier for me. I had crossed two oceans, been knocked about before by big waves. This experience had to be twice as hard for Noo, and heaven knows it was hard enough for me. I wondered if she was near the end of her tether.

The Queen of the Sea was merciful. Spinning slowly, Monique slipped back through the harbour mouth.

For a carton of Gudang Garams, a fishing trawler towed us out of Grajagan. We had to ask several captains before one agreed to do it. Being dragged through the waves at twice our regular speed gave us a wet, frightening ride, and we almost didn’t make it. Going into our sixth wave, the rope snapped. The faces of the dozen fishermen above us switched from laughter to horror. We were not yet through the surf zone, and the rocky side of the harbour entrance lay behind us. But tuc-tuc was spinning in the water, and with some vigorous spading, we had enough power to launch off the crest of the seventh prahu-cruncher and slam down in the trough beyond. After that, we were clear. The fishermen laughed and cheered. We drew alongside their boat and Nadya threw them the cigarettes, shouted “Terima kasih.” Thank you. Then we joined the prahu kecil on the beach to the side of the harbour, where we should have been in the first place.

I lay awake in bed listening to the sound of the waves, Noo fast asleep at my side. Her mauled fisherman’s hat hung on a nail by the window. It had been a quiet evening in the losmen. There were no other guests and we hadn’t spoken much to each other. I had gone for a swim to relax, tried to persuade Nadya to join me, play like we had at the start of our adventure. She’d declined. Didn’t want anything more to do with the sea.