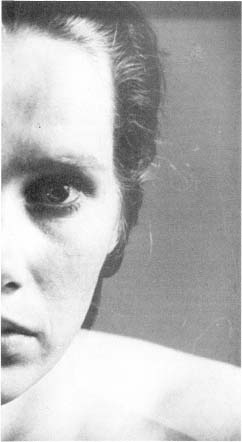

BERGMAN ON STAGE AND SCREEN: EXCERPTS FROM A SEMINAR WITH BIBI ANDERSON

Bibi Andersson’s 1990s appearances in several of Ingmar Bergman’s productions at the Royal Dramatic Theater continue a long collaboration that began with his films of the 1950s. These include The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Persona, and Scenes from a Marriage. This seminar, sponsored by the American Film Institute, took place in 1977.

QUESTION: The hazards of film work must sometimes make you long for the theater. You were, after all, trained for the theater, and you’ve often appeared with the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm. Do you intend to go on moving back and forth between theater and film as Bergman himself has done?

ANDERSSON: I love the theater I have been with. The problem is that if you are with that theater you have to be there twelve months a year. There is no such thing as leaving and coming back for guest appearances. I have tried to take half a year off and play the rest of the year, but it created so much jealousy, I decided that since I don’t want to be tied up by the theater for twelve months a year —I feel imprisoned a little bit — I had to choose, and so 1 have left the theater. It hurts. 1 would have liked to be able to do both, but that kind of jealousy is very hard in Sweden, and it’s even a drawback to have been abroad. Unless you come back as Greta Garbo, you’re not worth very much, and it’s sometimes frustrating. I had gone back to do Twelfth Night. Bergman wanted me to do it. I played it, but all the actors had a meeting. The result of that meeting was that neither I nor Max von Sydow should be allowed to come back again and play. A full commitment was required. There were so many girls for the parts. I can understand that. If you are in a theater and you work in all different parts, and all of a sudden somebody comes home and just nibbles and takes the best thing, it’s very frustrating.

QUESTION: But you’re not giving up the theater?

ANDERSSON: No, I will try to find other places to act.

QUESTION: Do you respond differently to a stage play compared to a screenplay? Does quality or the absence of quality matter more in one form than in the other?

ANDERSSON: A bad play will always be a bad play, no matter how much of a genius the director is, because there are certain things that the dialogue cannot cover. You cannot have a close-up and cover up what is said so loud that everybody is supposed to hear it. But a bad script can turn out to be a very good movie if the director has a very imaginative mind. He sees things and makes choices. So usually I don’t judge a film script from what I read. I have to judge It from the way the director talks about it, from what he tells me he would like to do, or why he sees me in the part. I have to be seduced into It, or at least I have to seduce myself if nobody else does, if I really want to do It. But I cannot say that I’ve ever read a film script and said, “Oh, that is such great literature.”

QUESTION: Then you would consider that screen-writing is not as important for filmmaking as the work of the dramatist Is for the theater?

ANDERSSON: Bergman, when he writes a script, writes it as a novel, and you know that whatever he writes will be in the film one way or another. He writes In such a way that you get seduced, you get Ideas. But other writers write lines, and whatever is supposed to take place between those lines is a secret between the writer and the director. Anyway, it’s not written In the script that they give me to read. It’s difficult to know how their minds are going to work. Maybe it’s just that I am not used to reading American scripts, but I find them usually very flat. It troubles me because I don’t know how to read them or to ask the right questions about them.

QUESTION: Bergman has said that what he does In a film sometimes is determined by what he knows of the actor or actress he wants. Have you found that?

ANDERSSON: Yes. I have a feeling that it’s mostly when he’s writing or when he’s casting that Bergman gives his direction. I don’t know, now that he’s going to do films out of Sweden, what kind of commercial aspects he has to have in mind. But I know that, before, it was the knowledge of a person that inspired him to write In a certain direction. Even if It was unconscious, I’m sure it was playing a big part. If he was at work on something and knew that one of his actress friends had a similar problem or attitude, he would use hen When I was reading a script, I tried to figure out what side of me he was trying to use now, or what had he seen, or what it was that he did not want. You can sometimes be very frustrated if you feel the part does not do you justice. When I read Persona I wasn’t flattered. I didn’t understand why I had to play this sort of Insecure, weak personality when I was struggling so hard to be sure of myself and to cover up my Insecurities. I realized that he was totally aware of my personality. I was better off just trying to deliver that. It’s a good way to know oneself. Sometimes I think artists instinctively are very good psychiatrists. I also think all parts have to be based on oneself, otherwise they will never come across.

QUESTION: What sort of environment does Bergman create on the set that allows you to flow in your acting?

ANDERSSON: You have to create that for yourself. But he has to create an environment of concentration—- it has to be quiet on the set; he doesn’t want intruders or visitors. Yet sometimes he creates a mood that frightens people; you need to be very tense, and the discipline can be quite tough. That might be very good in certain respects, but it can be easier to work with other directors, who are looser and more insecure themselves. They can help you to just go ahead with whatever you have. If you laugh or if you do wrong, it will not be interpreted as lack of discipline, which sometimes happens with him. But during filming for Bergman, the most important thing you feel Is that everybody, including, of course, Bergman himself, is focusing on what you are doing in relation to the camera —- and that’s important.

QUESTION: Some of your most memorable work was done in early Bergman films — The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries. That’s some twenty years ago. What’s your attitude today toward those films and your work in them?

ANDERSSON: I don’t feel anything for my work in those films. I love the films, still They are very vivid In my memory even If they’re twenty years old. But 1 have no connection with what I was doing then. I saw Wild Strawberries recently, and 1 thought 1 was terrible, terrible. But we were all rather corny In those days. There was a certain kind of acting that seemed different, or perhaps it had to do with the sound that came out different. I don’t know. The voices sounded different then; I hear them as being artificial Maybe that is why Î feel a certain distance when I see those films.

But it doesn’t matter. I’m proud of the films, but not with regard to myself. Persona, on the other hand, I’m still proud of. Each time I see it, I know I accomplished what I set out to do as an actress, that I created a person.

QUESTION: Would you say that film represented the difference between youthful work and mature work?

ANDERSSON: I think so, yes.

QUESTION: What survives very well from those films is a quality of innocence in your characters—particularly In The Seventh Seal, In which the character Is almost madonna-like.

ANDERSSON: When I was very young I had a certain kind of Innocence that, unluckily enough, life has not let me keep. I was Innocent in the sense that I was very trustful, I loved people, I loved life. But I was not shy. I was outgoing. I was myself In those clothes In The Seventh Seal, and I think It came out. When I see It today, I think it’s beautiful In those days, I was not being conscious of what I was doing. I was just trying to be natural

My part In Wild Strawberries Is much more complicated. I understood It all later. I remembered so well that Bergman wanted me to bring out something I wasn’t aware of in the dream scene in the woods when I am holding the mirror In front of the old man. He said, “You are youthful and cruel Because of your innocence you have no pity. Because of the way you are — happy, outgoing, curious —you judge and condemn people. All those young, beautiful qualities in certain situations are very brutal. Remember that.” He meant that at the same time that the young can be very charming, they can also be very tactless. They can say, “You are no good. What did you do with your life?” It’s so easy to say such things when you haven’t given your own life a try. He wanted me to project that kind of sudden coldness that a young person can have — coldness without pity.

It was a very interesting part, and I understood what Bergman was saying. But I’m not at all sure I knew how to play it. That’s why I was disappointed when I saw Wild Strawberries again. Realizing what a great part it was, I didn’t think I measured up to it.

QUESTION: Could you play that part today?

ANDERSSON: I would play it totally differently. I would not be able to play a certain kind of absolute freshness — of course. I could always act it, but today I would make different choices. I remember when I was rehearsing Twelfth Night for the stage with Bergman. I was going to do Viola. At first, we were just playing, and he said, “It’s so wonderful. You never change.” I started to work on the role, and I worked and worked. He said, “The more you work, the worse it gets. This part is not that complicated, just try to remember who you were twenty years ago. Play that. With what you have achieved since, that’ll be fine. Just go ahead and be happy and don’t think.” The nights I succeeded in doing that, I was good. But certain nights when I was too aware or conscious, I was less spontaneous. Acting is so fascinating when there is that mixture of being aware and of just letting yourself be innocent.

QUESTION: Your role in Persona is the one most often discussed, and there are any number of scenes worth discussing. For example, the strongly erotic scene in which you tell Liv Ullmann about a sexual encounter with two boys on a beach. It’s a long close-up on you, it’s all talk, but Pauline Kael has called it one of the most erotic moments in cinema. How did you bring it about?

ANDERSSON: I’ll tell you technically what happened. Bergman wanted to cut that scene. His wife had read it or — I don’t know — but he was advised not to keep it in. I said, “Let me shoot it, but just let me alter certain words no woman would say. It’s written by a man, and I can feel it’s a man. Let me change certain things.” He said, “You do what you want with it. We’ll shoot it, and then we’ll go and see it together.”

He was very embarrassed and so was I — I was terribly embarrassed to do the scene. We shot it in one long close-up in one take. Two hours. We started rehearsing at nine, and we were through at eleven. There was both Liv’s and my own close-up. Then we saw it, and he said, “I’ll keep it. It’s so good. But I want you, all by yourself, to go into the dubbing room, because there’s something wrong with the sound.” I didn’t think so. I had been talking very high, very girlish. So the whole monologue was dubbed afterward, and I changed my voice. I suddenly put my voice lower, and that I dared to do when I was totally alone and no one could watch me or see me or anything. That might be what gives the scene a certain intimate quality. But I never had that dream.

QUESTION: There is another scene — a gray, twilight scene — when you and Liv Ullmann meet in a room, and you seem to melt into each other. How did you approach that?

ANDERSSON: I remember the studio was full of smoke because it was going to be this kind of blurry thing. Ingmar had a mirror, and we also knew that one of the big problems with the shooting was how to compose the frames, when there were only two people all the time, without just having a reverse over one shoulder. How do you make us move in the same shots so that it will still have movement and be interesting and not boring? He wanted a mirror. He said, “It will be very beautiful.” He also said, “Move and we’ll see.” So we moved. Liv pulled my hair back, and Î took her hair. We didn’t know what to do, and we just tried to make the frame look interesting. Finally he said, “That’s it,” and they shot it.

QUESTION: What do you make of Personals ending? You’ve spent a period of time at the shore with Liv Ullmann as the patient and you as the nurse, and now you board a bus.

ANDERSSON: For me it meant returning to my life and world and that she was going back to hers. This was a meeting from two universes; they overlapped. I came out having gained a certain experience, and, hopefully, she with another. But as usual in life, what we have experienced, what might have changed us inside, doesn’t necessarily change the whole outside. We had just maybe gotten one new insight, one new approach to things. But we had borrowed the house for two months, and the time was up. She went first, back to the hospital 1 had to go back to the hospital, too, where I would continue my services as a nurse. Being the nurse, I was the servant, and I stayed to clean up the house. I remember I had terribly ugly rubber shoes on. 1 could hardly walk in them —- and that ugly hat.

QUESTION: I think some people might be disappointed with such an interpretation of the ending, wanting something more profound.

ANDERSSON: I think that for a while the two women really mingled, that 1 as a nurse understood something. Without explanation, I came very, very close to this woman. I understood her. I Identified with her, and I was even able to say things In her place. I’m sure all this will change the life of the nurse, because before that she had been very square. She had never used her Imagination toward other people; she had never analyzed what was happening to herself either. Suddenly, through the silence of the other woman, she was able to put herself in her place, understanding her world and her thinking and to express that.

QUESTION: Sven Nykvist has been Bergman’s photographer for most of his films. What relationship have you formed with him on the set?

ANDERSSON: Sven is a very shy and timid person. Lately, because he has gotten used to traveling and talking to people, he has started to talk much more. But when I used to work with him, he said about ten words to me during the whole shooting. What I felt from him was a great warmth. But sometimes if I was having a big fight with Ingmar, he would say, “Yes, go on,” though he wouldn’t dare have one himself. Sven and I and Erland Josephson, who played in Scenes from a Marriage and Face to Face, recently finished a film for television without a director. Erland wrote the script, and he and Sven formed a production company, and I participated. We said, “Why don’t we try to see how much we really contribute ourselves? Why do we need to talk to a director and explain to him what we want to do?” It was an experiment. We found out we needed a director. We liked one another so much that Sven was not capable of telling us that we acted badly, and whenever he asked me to look in the camera to see if I liked the framing, I was so flattered that Î just said, “That is so beautiful.” Maybe it will come out nice anyway, because we liked what we were doing. I haven’t seen it yet.

QUESTION: In all the years you worked with Bergman, something of a repertory atmosphere developed with such other performers as Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow. Many moviegoers must regard you as part of almost a family of very skilled actors. Do you in fact feel closer to Ullmann and von Sydow and others than to actors from other films?

ANDERSSON: Max and Liv, yes, I feel very close to them. I know how they think, I know how they work. This said, I can communicate as well with other people. If you arrive on a new set and work with new actors, everybody always makes an effort to find a means of communication. That is the common denominator between all actors.