A FILMMAKER IN THE BORDERLAND: BERGMAN AND CULTURAL TRADITIONS

MIKAEL TIMM

Mikael Timm is a cultural-affair s journalist, playwright, and film critic. This essay first appeared in the special tribute issue of the Swedish film magazine Chaplin, titled Ingmar Bergman at 70.

IN STUDYING THE EXTENSIVE LITERATURE ON INGMAR Bergman’s films, you very quickly detect a difference compared with what is written about other directors. People who write about Bergman focus very much on the “message” of his films, while relatively few detailed studies have been devoted to his aesthetics.

The same pattern repeats itself if you look at press archives and study interviews with Bergman. Time after time interviewers and writers return to such themes as religion, love, morality, and the role of art in society. Like no other filmmaker, Bergman has been given the task of being a “moral” guide for his contemporaries. This is no marginal position, no mere concession to a new art form. On the contrary, Bergman has been awarded a number of prestigious “humanistic” honors otherwise bestowed on mainstream writers and scholars.

Personal interviews with Bergman present the image of a titanic artist in the romantic tradition, with Bergman the man more in the spotlight than his work. At the same time, his movies provoke lively debate. Some critics and viewers search for a “prophetic” dimension, containing truths about human society, the “ego,” and the future. The filmmaker is assumed both to understand and to profess fundamental truths.

Personality cults are, of course, part of the cinematic tradition, but it is also unusual for new films to trigger serious debate. The seventh art was long regarded as an illegitimate form of culture. Whereas literary and art criticism has a tradition of painstaking studies, close readings, academic research, and self-evident participation in a broader humanistic debate, a long time passed before the cinema came close to achieving this role.

Even today, the difference between movie reviews and literary critiques in daily newspapers — at least in Sweden — is substantial, in terms of their level of ambition, the space allotted to them, and their frames of reference. And on television and radio, filmmakers are rarely asked the same kind of general questions about the spirit of their age that writers are somehow always expected to be able to answer.

Bergman is thus one of the few film directors whose works encounter the same kind of expectations as do the more traditional arts and literature. Nevertheless, the cinema was barely considered an art form at the time Bergman began his first film projects. One only has to glance through the contemporary reviews of the films he made In the 1940s and 1950s to see how even those films that today are considered classics and a part of our common cultural heritage were treated as trivial entertainment.

Even after Bergman had made his International breakthrough, a Swedish textbook for journalists during the 1960s found it necessary to point out that “when writing a film review, remember to mention who directed the film, because the director Is as Important to a film as a writer Is to a book.” There are additional examples, which say something about the role of movies In the cultural marketplace.

Like no other form of art, the cinema stands at the meeting point between “polite culture” and a traveling minstrel show. Many serious students of the cinema regard this situation as awkward, if not embarrassing. But as the case of Bergman demonstrates, It may also result In an almost unique range and intensity of contacts between the artist and his audience. As a filmmaker Bergman is part of an industry devoted to producing and distributing entertainment. At the same time, his films have become increasingly Important In our cultural life over the years.

In his capacity as a filmmaker, Bergman has experience of the different “cultural orbits” into which films can be placed. For many years, his films did poorly in commercial terms and his filmmaking could only continue because the Swedish motion-picture industry needed new products. Later his Swedish audience grew larger, while generally Sweden suffered declining film audiences, Bergman’s salvation at that point was foreign audiences, which often encountered his works by way of film clubs, art movie houses, and the like.

Whereas Bergman’s career as a filmmaker has been under threat on various occasions, he has not only been tolerated by devotees of polite culture — of which the theater is one part — bet also has been regarded as a theatrical director of extraordinary talent. He is, moreover, one of the most popular dramatists of his generation. Without viewing him from the standpoint of cinematic sociology, 1 believe that Bergman’s distinctiveness and experimental nature derive much of their energy from the fact that he works in different aesthetic traditions and with different audience situations.

Bergman’s cinematic production is commonly divided into phases: a first phase, in which he learned his craft and tried different means of expression; a second, in which he found his style — a “rose-colored” period — followed by a period of crisis, et cetera. This approach implies that there is an evolutionary process leading to a specific Bergman style, which can be defined and recognized.

This is a seductive line of reasoning and makes the role of the audience easier. But a quick look at Bergman’s film production, with Port of Call, The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring, Persona, Secrets of Women, From the Life of the Marionettes, Wild Strawberries, to. mention just a few examples, instead proves the opposite. There is an incredible range of variations in Bergman’s creations. Imagery, dramaturgy, conflicts, structure, the use of sound and music — all of these are different from film to film. During his long career, Bergman has never achieved one definitive style, but instead is continuously experimenting with new means of expression. He embraces and rejects themes, interpretations of characters, and narrative models — and returns to try them once more.

Bergman’s last theatrical film, Fanny and Alexander, can serve as a gateway into his works. The film very quickly became such a popular, well-established concept that today the Swedes talk about “Fanny and Alexander decorations” in store display windows, “Fanny and Alexander celebrations” during the Christmas holidays, “Fanny and Alexander families,” et cetera. For a Bergman work, the film was received with tremendous enthusiasm by an unusually large Swedish audience. Its drawing power was so great that the five-hour version did very well. It seemed as if the audience rather quickly reconciled itself with Bergman.

Fanny and Alexander transformed Bergman from a provocative filmmaker, whose greatest popular and critical successes of the preceding decade had occurred abroad, almost into a Swedish popular artist. The enthusiasm of the reception indicates that Bergman had previously been a provocateur of the first rank. What many people found appealing about Fanny and Alexander was the sense of harmony that characterizes the plot, especially in the five-hour version. All the conflicts are fully developed, the peripheral themes are interwoven elegantly and used to illuminate the main story; there is a powerful but seemingly effortless forward movement through the film. The dramaturgy, the linearity of the story, the set design, the actors’ performances — everything fits together, in a way reminiscent of the great nineteenth-century novels.

Here are the forces of evil and good, men and women, childhood and aging, love and hate, individuals and groups, God and worldliness, faith and doubt, city and country, realism and dreams, water and fire. There are many pairs of opposites, but although the plot is fairly complex, with its entanglements and important side-intrigues, the story is constructed with almost inexorable stability. There may admittedly be shades of Griffith and Sjöström, but even clearer are the echoes of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Thomas Mann, Dickens, and Balzac. Fanny and Alexander is of course a cinematic tale, but it is very firmly rooted in the major epic novel tradition.

As an individual film, Fanny and Alexander is a remarkable accomplishment. It appears even more remarkable if we look at Bergman’s entire list of film credits. In the four preceding years, Bergman had made From the Life of the Marionettes, The Farö Document 1979, and Autumn Sonata. It may seem almost incomprehensible that a single artist could work in such different genres with such good results. Although other filmmakers and, not least, film critics have often used the concept of the “Bergman film,” it is difficult to see the kind of uniformity this phrase implies, either in terms of style or in choice of subject matter.

Sometimes Bergman’s unique position in international cinema has been explained by the fact that he works with what might rather clumsily be called the “intimate sphere of the bourgeoisie.” The idea here is that in numerous cultures, the bourgeoisie is similar and many moviegoers will therefore recognize what they see in Bergman’s films. But this explanation is hardly sufficient, either to account for the exceptional response Bergman has elicited or to give his films any kind of unity.

The genres that Bergman works with are not unique to him: marriage dramas, historical films, contemporary psychological dramas, et cetera. Plenty of filmmakers have moved in the same cinematic landscape. Yet Ingmar Bergman has earned himself a special role in cultural life, unlike that of almost any other filmmaker. His films have been analyzed in terms of their ideas, morality, and ideology. Polite culture, which otherwise hardly admits movies into its world, has been very generous in Bergman’s case. Why?

It is reasonable to seek the answer not in the themes or the aesthetics of his films, but in the tension between the ethical conflicts explored in these films and their aesthetic aspects. Such a reading emphasizes the breadth of Bergman’s artistry rather than its uniformity, its dynamism rather than its clear-sighted stillness, its endeavors rather than its solutions. To me, Bergman’s artistry is not of a kind that one can summarize and then file away. On the contrary, it is uneven and unfinished, and this is precisely what gives it a sense of urgency.

In Bergman’s filmography, we can see a reflection of the entire cultural journey of the twentieth century. Of necessity, it is restless. It includes the great novelistic tradition, the work of early experimenters such as Meyerhold, modernism’s dissolution of form and approach to time and space, naturalism, the eighteenth-century tradition of erotic wit, archetypal characters such as Faust, a Nordic tone in portraying the interplay between man and nature, the alienation of the bourgeois family, and even some direct political references. In short, Bergman has based the creation of his films on the European cultural heritage before and outside cinematic art.

In his recent book The Magic Lantern (La-terna Magica) and In certain Interviews, Bergman has told about his childhood and education. Although these events occurred only fifty or sixty years ago — when dadaism, symbolism, modern theater, Industrialism, et cetera, were making their breakthroughs in Sweden — his origins are skewed more toward the social views and culture of the nineteenth century. It is a tradition where the writer served as a revealer of truths, where such Protestant concepts as guilt and responsibility were pivotal, and where it was farfetched to regard culture as a weapon or even as a force opposed to the stability of the bourgeois world. The works of art this culture created are in no way Impoverished or simplistic. On the contrary, its heritage in the fields of prose, music, and the visual arts has turned out to be extremely vital. At the same time, this was the environment from which all of our twentieth-century attempts at cultural upheaval emanated.

The social opposite of this affluent Protestant milieu Is, of course, the theater, which was hardly considered a defender of bourgeois ideals, despite the evolution it has gone through since the days of Molière and Shakespeare. When Ingmar Bergman began working In student theater, It was at a time of transition: the nineteenth-century tradition In acting styles, Interpretation of works, and scenic design still survived on the major national stages, while at the same time modernism had made Its breakthrough with full force and had already begun to establish its own traditions in other countries. Bergman’s theatrical successes have sometimes been described as consisting mainly of unusual skill in instructing his players, but this is probably a simplification that leaves out most of the truth. On the contrary, many Bergman productions (I will choose examples from a small portion of Bergman’s work) evidence a great familiarity with experimental theater. To take jest a few examples: In Woyzeck, several productions of A Dream Play, and King Lear, Bergman’s work utilizes drastic contrasts, simplifications, fast tempos, stylizatlons, et cetera. At the same time, he has directed productions of Shakespeare that neither hark back to the Elizabethan tradition nor base themselves on the Institutional theater style that has its roots in the nineteenth century. As for his productions of the classics, one can speak of a respectful but not literal reading of the original texts.

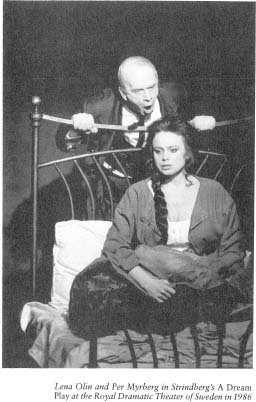

In his theatrical productions, Bergman explores the same two traditions he does in his films. There has been a series of almost naturalistic productions (to take a recent example, Strindberg’s Miss Julie In 1985), In which the director alms at the greatest possible degree of reality. On the other hand, there are productions such as Woyzeck (1968) and A Dream Play (1986) that are directly linked to twentieth-century experimental theater, abrupt, quick contrasts, daring set design, stylization, and brutal rhythm.

Obviously Bergman has used knowledge gleaned from his theater productions in his films, but, although this applies largely to his way of instructing the actors, there has also been a transfer of experience on another level. There are natural connections between modernism in the theater and experimental cinema. Even In Bergman’s most daring films, where his narrative Is most difficult to penetrate, it is clear that he has brought with him from the theater a respect for the rhythm of the actors in a particular scene and, not least, the realization that he must keep the audience with him. Some of his later films, such as Autumn Sonata, are sedately divided into “acts” and certain scenes open In a manner reminiscent of Ibsen.

By way of summary, In his theatrical work Bergman is even less faithful to any stylistic ideals than in his films: the range of playwrights — from Büchner to Ibsen to the dramas of classical antiquity — Indicates that here, too, he can alternate between different traditions and dramatic styles. It becomes clear from his various Strindberg productions that Bergman is capable1 of trying very different approaches to the same text. He does not arrive at a definitive interpretation of a play.

It is thus not possible to trace any mechanistic connection between Bergman’s work In the theater and his filmmaking. As we know, it eventually became his routine to direct several theatrical productions each year, then with equal regularity use almost the same actors to make films during the summer. Obviously there is a connection, but it is more on the level of professional skills than of textual interpretation and aesthetics.

Having reached this point, it remains to be observed that the concept of a “European cultural heritage” is so general that it risks being unmanageable; It can encompass everything and at the same time be so vague in Its contours that It becomes almost invisible. But the interesting thing about Bergman is that he does not assume a fixed position. In Bergman’s work there is a continuous “rereading” of the classics and the aesthetic de. bate. At the same time, In his films he returns to the same moral themes, but only partly. Bergman’s circle of motifs has expanded over the years.

The overall Impression Is that Bergman Is constantly on the borderline between a harmonic approach to culture and a dissonant one. He Is sufficiently skillful as a professional to succeed in holding together almost every film; the disunity of his vision is apparent only when you compare his films with each other.

It is not unique for a director to work at the point where different traditions Intersect. On the other hand, it is unusual for him not to seek safety on one side of the border or the other, but Instead to constantly alternate back and forth between them. Bergman does not accept with open arms the cultural heritage he receives. He Is always thinking about rejecting It. There is a kinship of choice with other writers who worked in the same kind of borderland, such as Strindberg, Chekhov, and Pirandello.

Bergman has generally written his own screenplays. Most of his scripts have eventually been published. It was, admittedly, not Bergman’s original Intention that these scripts should be treated as literary works. The text is written In a coherent manner, yet, although his final films are often characterized by a strict and firm structure, his screenplays are “open.” For example, they contain descriptions of smells and moods, which are not ordinarily found in a screenplay. Bergman’s intention has been that these descriptions should inspire his various colleagues, set designers, and costume makers. But at the same time, these elements obviously make a Bergman screenplay resemble a lengthy short story or a short novel

Without stretching the parallels too far, there are clear similarities with the prose of Chekhov and Turgenev. Bergman provides Intimate descriptions and uses concrete details, from which the reader himself can construct the settings. There are elements of multileveled dialogue (sometimes small talk that floats past, sometimes confrontations), and an all-knowing narrator describes the state of mind of the main characters concisely and exactly, but without interpretations.

From Strindberg, Bergman borrows those techniques that are closest to the cinematic medium: precise details, lightning-fast changes of scenery, caustic dialogue, disruption of bourgeois harmony. It may seem a long way to Pirandello, but Bergman is Swedish in the same way that Pirandello Is Sicilian: on an archaic, mythic level. Where Pirandello uses the sharp light, the smells, and the evident Catholicism of his landscape, Bergman uses Nordic mildness (sharp light stands for something frightening and evil In Bergman’s films), the gray shades of his landscape, and its doubting Protestant pastors.

Many of Bergman’s films are about writers, artists, and musicians, but above all he returns repeatedly to artists who inhabit the fringes of the artistic establishment: jesters, magicians, mystics. In a number of his films, Bergman travesties theatrical conventions, employing certain kinds of dialogue and humor and being faithful or unfaithful to a genre. His masterpiece here Is Smiles of a Summer Night, which has very properly also been presented on the stage (with some difficulties) as A Little Night Music. Bergman chooses a discreet cinematic language. The editing of the film reinforces the dramaturgy, and the camera Is used In a way that enables the actors to work with nuances that suddenly bring the genre alive. A rigid, ritualized drawing-room comedy gains a kind of Intimacy through facial expressions, gestures, et cetera. All the people play roles and somehow realize their fates during a magic summer night. They are all standing on a stage.

Although a few writers, critics, or other scribblers pop up as characters in Bergman’s works, the relationship between his films and literature is more complex and indirect than it Is between his films and the theater. There are sometimes similarities in the narrative structure of prose works and films. This may apply both to the great European nineteenth-century novel and to experimental storytelling, as in his film Persona. On those occasions when Bergman uses a storyteller who turns directly to the audience, he sometimes does this to establish a kind of intimacy, as In a short story, and less often as a Brechtlan distancing device. The artists, writers, musicians, actors, and jesters appearing in Bergman’s films have in common that they very rarely find salvation and peace through their profession. It requires a moment of inattention on the part of fate if a jester is to escape demise and enjoy a little more of the good life.

It is generally fruitful to examine how Bergman uses dramatic climaxes and periods of rest, moments and continuities in his films. He combines his experience in the theater with both nineteenth-century epics and modernism in an eclectic fashion. In Bergman’s hands, the cinematic medium is consistently a genuine fusion of art forms. The disunity in his script, for example, may find its counterpoint in his choice of film music. Bergman often contrasts a modernistic pictorial imagery with harmonic music. In other cases his imagery provides a frame of reference for other periods and works of art (the Middle Ages, Chekhov, the 1920s).

The epic structure of Fanny and Alexander is clear. In other cases the narrative has a fundamental pattern while the direction, rhythm, and acting diverge from the epic style and instead approach a dramatic one (for example, Scenes from a Marriage). His television series are Interesting in this regard. In many ways, they resemble the nineteenth-century novel in terms of their actual production, their division into episodes, and the themes and characters that come and go. It is no coincidence that Bergman, who balances on the borderline between traditionalism and modernism, has become a significant Innovator of the television medium, especially with his narrative series. TV drama Itself seems destined to be forever stuck in nineteenth-century conventions, which are reproduced with state-of-the-art technology.

As for Bergman’s relationship to the European cultural heritage, Swedes cannot close their eyes to the fact that people in other countries have often considered his films typically Swedish, not European. One reason Bergman’s films have attracted so much attention outside Scandinavia Is the “exotic” settings in which the stories take place. When Swedish movie buffs traveling abroad have been asked about Bergman’s films, more than one has probably replied, “No, actually Sweden doesn’t look like it does in Bergman’s films,” Most Swedes do not live In Isolated houses in the countryside, most of them are not grappling with religious Issues (or at least don’t want to admit it), and, with the exception of some of his early films and the two TV series Scenes from a Marriage and Face to Face, most Swedes’ manner of speech is different from that of Bergman’s characters.

We know that films from a small remote culture have an exotic charm, yet audience reactions and reviews show that Bergman’s works have an impact on people from other cultures in an apparently straightforward way. Bergman stands with both feet in the mainstream European cultural tradition, and this is a common platform for many people — regardless of what language they speak. It is also significant that a Japanese director such as Kurosawa, himself unusually Western in his education, feels a close kinship with Bergman’s films. Like Shakespeare’s England, Bergman’s Sweden is a stage. Added to this is a more recent cultural heritage in which the landscape plays the part of the soul.

But if Bergman had merely contented himself with furthering a European cultural tradition — taking issues and character portrayals mainly from the nineteenth-century novel and putting them into a new art form — his films would have been not much more than workmanlike pieces. They would hardly have attracted such great attention and would not have earned him such a central position in cinematic history.

Bergman’s decisive contribution is that, like all major artists, he has managed to renew not only his art form but also our way of viewing our own age. Just as all the early modernists had a well-defined bourgeois tradition as their starting point (Baudelaire, Appollinaire, Rimbaud, Du-champ, Weill, Brecht, Stravinsky, Picasso, and others).

Bergman’s work presupposes both a clear tradition and the need to depart from it. He is both a symbolist and skeptical of his symbols. He does not rely on the results of his labor (it is striking how critical he is of both his films and theater productions). All he relies on is his working methods, his professional experience. His reexaminations employ the same tools that were used to build tradition.

In various contexts (most recently in The Magic Lantern), Bergman has stressed how important the theatrical tradition has been to him. From Torsten Hammaren and other stage directors he gained professional experience; they taught him the importance of thorough preparation, punctuality and discipline, respect for the actors’ rhythm, and so on.

At a young age, Bergman became the head of a typical bourgeois cultural institution — a small provincial theater. Through all his crises and doubts, he has been faithful to institutional thea-ters. In the theater, the transfer of knowledge from one generation to another is a much more broad-based and living process than in literature and cinema, simply because a theater is a collective workplace that is in continuous operation.

With his roots in institutional theater, Bergman has been very much in the center of the clash between cultural heritage and innovation that has characterized twentieth-century aesthetics. When Bergman was a young director, there were still actors who worked completely in a nineteenth-century spirit. Meanwhile, the influence of Meyerhold and, later, Stanislavsky, Gombrowicz, Artaud, and many others was reaching the major institutional theaters in Sweden,

Although the cinema was long regarded as an illegitimate member of the cultural family — a role played today by video production — this young art form cultivated its own traditions all the more intensively. Young directors have always sat glued to their movie-house seats watching the works of previous generations again and again.

Sweden, too, has a silent-film tradition that must be considered unique compared with other art forms, and in many contexts Bergman has stated how he was influenced by Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström. But, as I have indicated, there is nothing unusual about a film director studying the works of his predecessors very carefully. What is original about Bergman in this respect is not that he is closely related to Swedish or foreign cinematic traditions, but that he assumes that a film can be used to portray the same psychological processes as a novel.

A number of Bergman’s films include the theme of the artist who is simultaneously drawn to the secure bourgeois life and rejects it. There is a bit of Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kröger in several films. The more mature Bergman becomes as a filmmaker, the more caustically and inexorably he focuses on the destructive forces that flow beneath harmonic culture. Doubts and anxieties beset his characters. When war itself breaks out, there is no beauty — as is otherwise common in war films — but instead he shows naked and crude destructiveness, in the tradition of Büchner and von Sternberg.

What characterized Bergman’s first period as a film director was his close adherence to existing genres. Unlike many young filmmakers of today who try to debut with radically different films, Bergman first tried to learn his craft. Later, after his cinematic artistry had matured, the influence of the theater was clear. The peak of this phase was Smiles of a Summer Night, which resembles a short story by Hjalmar Soderberg, Marivaux, or Lubitsch, but where theatricality — in the good sense — predominates.

In the 1960s Bergman entered a new phase: his films became increasingly experimental. This coincided with experiments in European theater and literature; Sartre and Camus were both dramatists and passionately interested in the cinema. Yet unlike Sweden’s other great postwar film and theater director, Alf Sjöberg, Bergman rarely made any clear references to sources of intellectual inspiration or artistic isms imported from elsewhere.

Although many directors almost brag about how little they see of the works of contemporary filmmakers, throughout his career Bergman has carefully kept up with films. He has also devoted great attention to music and art. Despite the lack of references to aesthetic formulas, one can therefore assume that Bergman has been well aware of the debate over different aesthetic models, not least modernistic ones.

He himself has never presented a formula for how a good film or theater production should look. Instead, he has spoken in many contexts about the craft-related aspects of his profession, and about his respect for such knowledge. This respect has grown over the decades, but no correspending artistic model has emerged. He always continues his work by positioning each individual film and theater production at the spot in the aesthetic field where different forces and energy are at their greatest.

At the same time, his professional skill has continuously increased. The more he has mastered his means of expression, the more critical he has become toward his works. Instead of polishing his style, each film has served as a new contribution to his continuous test of “the potential of contemporary art.” In other words: where should we stand on the scale between traditionalism and modernism?

On those occasions where Bergman has tried to be “topical” — to make clear references to a historical situation, as in The Serpent’s Egg — this very quality has weakened his work. While other directors regard topicality as a source of energy that helps fuel their work, Bergman becomes bound by the limitations of the topical, because for him every individual film or theater production is a “project” where the creative process is replayed from the beginning.

Concretely, he can use his experience of actors working with conventional texts, where uniformity of interpretation is emphasized as a way of enhancing the power of modernism’s fragmentary view of humanity. His experience of earlier productions makes him more familiar with the mechanics of the production process, but each time the results are unpredictable, He has a natural affinity with the high point of nineteenth-century tradition, just as it was approaching its own breakup and transition to modernism.

Bergman’s latest theater productions, King Lear and Hamlet (in my opinion, the latter has been reviewed insensitively in Sweden), show his strong desire to experiment. In both productions, especially Hamlet, he stakes his whole reputation on the acting, challenging the text, the actors, and the audience instead of falling back on the kind of conventions that seem close at hand. This 1986 production of Hamlet, with its strong stylization, Its provocative elements, and its almost brutal rhythm, might have been the work of a young director at the beginning of his career. Yet precisely because of his familiarity with traditions, Bergman can use every project to find a specific aesthetic language.

Bergman’s works —that is, his Individual films — have given powerful Inspiration to artists In different genres, but because he straddles two traditions there has never been any “Bergman school” in theater or cinema.

In his constant desire to be ready to réexamine his achievements, to surrender the fort, and, after winning a battle, to be prepared to lose the next war, Bergman Is ethically similar to such doubters as Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy and aesthetically to such modernists as John Coltrane, Stravinsky, Strindberg, and Picasso, Of course not everything these men produced was good, but their art lives on. So will Bergman’s. For although today’s young directors cannot work in the same fashion in the borderland between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they have made similar aesthetic-strategic choices — to adopt a particular style, to develop a coherent aesthetics, or, like Bergman, to move between different positions and draw their strength from these constant changes themselves.

It seems unnecessary to add that Bergman’s refusal to make definitive choices has been fruitful. It is necessary for the audience, like the seventy-year-old director himself, to risk everything on each new work. Bergman’s work Is not over, nor can it be over as long as one views his films with an open mind.

Translated by Victor Kayfetz