BERGMAN’S TRILOGY: TRADITION AND INNOVATION

ROGER W. OLIVER

Nothing changes more constantly than the past; for the past that influences our lives does not consist of what actually happened, but of what men believe happened.

— Gerald White Johnson

The past is the present, isn’t it? It’s the future, too. We all try to lie out of that but life won’t let us.

— Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night

THE INESCAPABLE INFLUENCE OF THE PAST ON THE PRES-ent is probably the keynote to naturalism as a literary/dramatic theory. Since heredity and history are two of the determining factors of naturalism (along with environment), the actions of the characters in naturalistic plays are inevitably shaped by the past. For a director staging the works of such playwrights as Ibsen, Strindberg, and O’Neill today, the challenge is not only to convince a modern audience of the acceptability of such a deterministic philosophy, but also to avoid the tyranny of the past imposed by more than a century of naturalistic productions.

While Ingmar Bergman’s productions of Miss Julie, Long Day’s Journey into Night, and A Doll’s House may not have been initially conceived as a naturalistic trilogy, they functioned as such when viewed in this order, the order in which Bergman directed them and the Brooklyn Academy of Music presented them, in 1991, as part of the second New York International Festival of the Arts. Each production clearly delineated the themes and conflicts of the individual play in and for itself; taken together, however, the three stagings illustrated not only the kinship between the three plays thematically and stylistically, but also Bergman’s evolving approach to reconciling traditional and contemporary theatrical practices. Although Ingmar Bergman has been associated with the Royal Dramatic Theater of Sweden (Dramaten) since I960, these three productions represent some of his work with the company since his return from his self-imposed exile in Germany. The oldest of the three productions, Miss Julie, was first presented in Stockholm in 1985 and is based on a production he first staged in Munich. In certain ways it is the most “traditional” of the three stagings, retaining the kind of meticulously detailed mise-en-scène usually associated with plays of this type. Yet even within the context of a “realistic” presentation of the play, Bergman is able to make discoveries about the work that illuminate and enliven it for a contemporary audience.

The close connection between tradition and innovation in Bergman’s work can perhaps best be illustrated by the physical appearance of Miss Julie herself. When German playwright Peter Weiss was consulting the original manuscript of the play in preparing his text for Bergman’s Munich production, he discovered a reference to a scar Miss Julie bears on her face from a whipping by her fiancé. Weiss and Bergman decided to restore the scar, which Strindberg himself had deleted, since It visually establishes Julie’s vulnerability and provides further motivation for the fear and loathing of men she exhibits during the course of the play. According to Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss, who designed all three of the Bergman productions seen at BAM, Bergman connects this scar with the one Julie receives as a result of her loss of virginity during the Midsummer Eve Interlude and her anticipated use of the razor provided by Jean at the play’s end. Julie’s victimization at the hands of the men in her life thus encompasses not only the neglect by her weak father but also the physical abuse by her fiancé, and the seduction and then betrayal by Jean.

Perhaps the most effective demonstration of Bergman’s ability to use realistic detail to create the world of the play onstage occurs in the Midsummer interlude. While Jean and Julie are offstage In Jean’s bedroom, Strindberg calls for the following scenario:

Led by the fiddler, the peasants enter In festive attire with flowers in their hats. They put a barrel of beer and a keg of spirits, garlanded with leaves, on the table, fetch glasses, and begin to carouse. The scene becomes a ballet. They form a ring and dance and sing and mime: “Out of the wood two women came.” Finally they go out, still singing.

For Bergman the scene becomes less a festive folk ballet and more a richly detailed exchange between individualized figures who party, drink, and explicitly express their sexual desires. Since some of the peasants have entered the kitchen previously, looking for water, there is a sense of continuity within the life of the household as well as the play itself. Strindberg’s dramatic device for eliminating an Intermission and allowing sufficient time for a significant action to occur offstage has been heightened by Bergman Into a variant of the passions being expressed by the central characters offstage. Even though the peasant couples are not given dialogue, their body language, gestures, and actions clearly convey the reality of Midsummer Eve.

This reality is underscored by Bergman’s casting and conceptualization of the role of Kristin, the cook who rules over the kitchen and Is also Jean’s fiancée. Kristin is often cast so that her stolidity and plainness contrast with Julie’s neurasthenic vibrancy. By choosing an attractive young actress, Gerthi Kulle, to play Kristin, and directing her to explicitly express her sensuality, Bergman emphasizes her needs and helps motivate the tenacity she exhibits in fighting Julie for Jean. When Kristin is left alone In the kitchen, for example, Instead of curling her hair, as Indicated in Strindberg’s stage directions, in Kulle’s performance she washes her upper body, including her breasts, slowly and sensuously, simultaneously expressing her need to refresh herself after working In a hot kitchen, and her awareness and appreciation of her own physicality.

In all three Bergman productions seen at BAM, in fact, it was the physical relationships of the characters as they interacted with each other and their environment that communicated the director’s vision of the plays. For example, the way in which Peter Stormare, as Jean, opened the bottle of wine, smelled the cork, poured some into a glass, and then tasted It perfectly expressed the character’s peculiar amalgam of aristocratic hauteur and servility. The brutal way in which he threw Lena Olin’s Julie to the floor underscored the antagonism as well as the attraction he felt toward her. According to several members of the Dramaten, Bergman stages his productions very meticulously, providing the actors with specific movement patterns as well as physical actions.

Bergman’s willingness to adjust his production to fit the individual actor, however, is illustrated by a crucial change in costume for Miss Julie. The working kitchen that Palmstierna. Weiss has provided for this production is in various shades of gray, on which Hans Âkesson’s lighting can create stunning effects marking the passage of time and change of mood* When Bergman first created this production for the Dramaten, the actress playing the title role — Marie Göranzon — wore a lavender dress that fit in with the color scheme of the room and suggested a sense of belonging, despite her status as the mistress of the house. For the performances at BAM, where Lena Olin assumed the role of Miss Julie, a red dress was substituted, reinforcing the passionate intensity and fierce individuality the new actress brought to the role. In this version, when Miss Julie changes out of her red dress into her traveling costume in anticipation of her departure with Jean, her loss of control is underscored by the fact that she no longer dominates the stage visually the way she did previously. In certain ways this production is the apotheosis of naturalism, with each physical and visual detail made as telling as possible to contribute to the vitality and verisimilitude of the whole.

With his production of Long Day’s Journey into Night we see Bergman moving toward a more abstract approach to naturalism. Instead of the minutely specific setting she created for Miss Julie, Palmstierna-Weiss has ignored O’Neill’s stage directions for a reconstruction of his parents’ Monte Cristo cottage. The play’s action takes place on a platform set within a void. In addition to a few chairs, the room is furnished only with a religious statue on a pedestal on one side and a liquor cabinet on the other. Occasionally, projected images, like the exterior of the house or a large tree, appear on the rear wall; otherwise, the action unfolds on a sparsely furnished platform surrounded by black curtains.

Bergman’s approach to O’Neill’s text also invites us to view the play in a new way. (This is perhaps the time to note that the Dramaten gave the world premiere performances of Long Day’s Journey into Night, in 1956, with Jarl Kulle, the actor presently playing the father, James Tyrone, in the role of Edmund.) Unlike most productions, where there are two intermissions or one inter-mission between Acts II and III, the Bergman version pauses after the third act, thus making the daytime and early-evening action continuous and isolating the final midnight scene. Substantial dialogue is cut throughout the first three acts, including all of Edmund’s story about the pig farmer and the oil tycoon that O’Neill later dramatized in Act I of A Moon for the Misbegotten,

The main effect of this theatrical structure is to place the emphasis on Mary Tyrone in the first part and the three Tyrone men in the second. There is no question that Mary is the focal point in the first three acts of O’Neill’s text. But by presenting these three acts as a unit, Bergman underscores her descent into a drug-induced fog to escape her fears over Edmund’s illness. Bibi Andersson’s unforgettable portrayal of Mary stresses the physical and emotional pain the character suffers, graphically depicting the agonized despair created by her alienation from family, friends, her past, and even her own body. All four actors portraying the Tyrones (in addition to Kulle and Andersson, Thommy Berggren as Jamie and Stormare as Edmund) perfectly capture the complex love-hate relationships of the play and the alternating rhythms of infliction of pain followed by the search for forgiveness.

By emphasizing the split between the part of the play dominated by Mary and the final scene, in which the men try to understand and gain pardon from each other, Bergman allows his audience to become more aware of the kinship between Long Day’s Journey into Night, Miss Julie, and A Doll’s House. Like the earlier playwrights, O’Neill is exploring the complexity of the male/ female relationship and its dependence, not only on inherited distinctions of gender but also on social roles and conventions that are part of the individual and collective history of the characters. Mary, like Nora, has gone from her father’s house to her husband’s, though she complains that James has never really given her a proper home.

To stress the difference between the world of the first three acts — Mary’s world — and that of the final act — the men’s domain, Bergman and Palmstierna-Weiss shift our perspective for Act IV. In his stage directions O’Neill calls for one living-room setting throughout, informing us that at the rear are two double doorways with portières, one of which “opens on a dark, window-less back parlor, never used except as a passage from living room to dining room.” By substituting a different set of chairs for the ones used in the first three acts and turning the statue and liquor cabinet around, we see that the men, like wounded animals, have retreated into their lair to lick their wounds after Mary has once again failed to kick her addiction.

In this final act, moreover, Bergman brilliantly ties his visual and structural approaches to the play together. Peter Stormare has been quoted as saying that instead of doing Long Day’s Journey into Night as a realistic play, Bergman “wanted to do it more like a. dream that becomes a revelation in the night.” It is through Stormare’s portrayal of Edmund that Bergman achieves this sense of dream/revelation. When Edmund speaks to his father about his experiences at sea, instead of speaking extemporaneously, he reads from a notebook, Edmund has already begun to transmute his life into art. At the play’s end, when Mary intrudes into the men’s drunken world dragging her wedding gown (in this production accompanied by the maid, Catherine, whom she has awakened), the characters do not all remain onstage in the dazed tableau suggested by O’Neill. James and Jamie accompany Catherine as she attends to Mary, and Edmund remains onstage alone. He then takes out his notebook and begins to write. The “play of old sorrow” as O’Neill himself called Long Day’s Journey into Night has both ended and just begun.

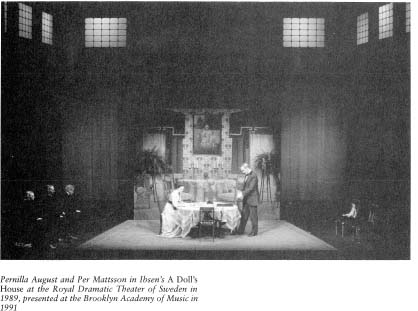

Bergman’s version of A Doll’s House both continues and extends the movement toward abstraction and textual distillation found in his production of the O’Neill masterpiece. Once again the design is dominated by an island-like platform that is sparsely furnished. Here there is a greater sense of containment, however, as high walls extend the entire height of the sides and rear of the stage. While there is seemingly more of a nod toward realistic detail in the presentation of the Helmer home, the black-and-white photographic blowups used for this purpose also serve to emphasize Bergman’s lack of interest in naturalistic illusion.

This denial of theatrical verisimilitude is reinforced by the chairs on either side of the acting platform. Here the actors who are not on stage in a particular scene sit in full view of the audience. When they are to appear in a scene, they make a swift, immediate entry, not only accelerating the pace of the action, but underscoring the ways in which the lives of these characters are tightly interwoven.

One of the great achievements of this production is the extent to which Bergman has liberated A Doll’s House from its well-made-play baggage. Although reinforced by the production, it is in the text he has helped fashion from Ibsen’s original that this accomplishment chiefly lies. By eliminating completely the peripheral figures of the nurse, housemaid, and porter, and reducing the number of the Helmer children from three to one (a daughter, Hilde), Bergman concentrates the focus even more tightly on Nora and her relationships with Torvald, Dr. Rank, Krogstad, and Mrs. Linde. He then goes even further by downplaying the resolution of the actions involving the latter three characters, so that we are really concerned only with Nora and Torvald in Act III. Thus only Mrs. Linde comes to the Helmers’ house at the beginning of the act, and there is no card from Dr. Rank in the mailbox announcing his imminent death.

By this third production in his “naturalistic trilogy” Bergman is willing to intervene more drastically into a play’s structure so that he can rid it of melodramatic effects and make the characters’ actions more plausible. He not only cuts substantial material from the early part of the act but also restructures the latter part so that Act III is played in two scenes rather than one. The first scene concludes in the middle of the Nora-Torvald confrontation, after he learns that Krogstad will not expose Nora’s actions. Rather than thank Nora for her love and sacrifice in borrowing the money that helped save his life, Torvald offers to forgive her, acknowledging that he will have to be even more protective of her in the future.

Instead of an immediate segue into Nora’s announcement that she is leaving Torvald and her family, the curtain falls. When it rises on the second scene, several hours have passed. Torvald is in bed, naked except for the sheet covering him. We are to infer that he and Nora have slept together, perhaps in one last attempt on her part to see if there is anything that can keep them together. Torvald’s words, “Why, what’s this? Not in bed? You’ve changed your clothes,” thus take on a much greater significance. As Nora reveals her epiphany to Torvald, he is not only naked, defenseless against her accusations and analysis, but also immobilized, lest he offend decorum. When Nora makes her exit, through the audience, she has separated herself from him unequivocally. The sound of the slammed door reinforces the finality of her action. By separating the scene into two parts, with the suggested time passage in between, Bergman has allowed his Nora to come to a conclusion that is well thought out and therefore more convincing.

The care with which Bergman builds to this final scene is evident throughout the production. From her first entrance Pernilla Östergren’s Nora has suggested the character’s strength and determination. She plays the submissive and fluttery role that society and her husband demand of her, but without sacrificing her Inner sense of self-worth. When she realizes that she is totally confused by the mixed signals the men In her world have sent her, she decides she must strike out on her own. How can she teach her daughter how to behave in this society when she doesn’t know herself?

Balanced against Östergren’s strengthened Nora is Per Mattsson’s Torvald: less the priggish male chauvinist and more the prisoner of values he has Inherited and unquestioningly accepted. Stripped of the trappings of the well-made play, A Doll’s House Is more clearly a play about people threatened by old values and the behavior they generate, Nora and Torvald also come to seem the victims of their materialist society. With his promotion at the bank, the Helmers have finally “made it” and Torvald Is terrified of anything that might threaten his position and authority, Bergman’s production thus highlights the connections Ibsen makes between patriarchy, materialism, and suppression.

Taken together, then, these productions reveal a double progression, thematic and theatre cal. Thematically Bergman is examining these plays as three alternative examples of male-female conflict within a materialist society. In Miss Julie sexual antagonism reinforced by class differences results In death. In Long Day’s Journey into Night the dependency caused by traditional gender roles leads to drugs and despair. It Is only when an Individual like Nora Is willing to make the courageous (and antisocial) act of leaving material comfort and security behind that freedom and self-knowledge is even remotely possible, though by no means a certainty.

Just as Nora Is forced to view the past in a fresh way during the course of Ibsen’s play, so Bergman forces us to look at these plays anew, both individually and In relation to each other. He accomplishes this by progressively stripping them of the naturalistic theatrical trappings that might have been necessary when first produced but now may obscure more than clarify. With A Doll’s House, the earliest and the most familiar of the three, Bergman must take the most radical approach, both textually and theatrically, so that the essence of the play can be revealed. Like an expert stripping a painting of layers of accretions so that the original underneath can be revealed, Bergman and the artists of the Dramaten enable a contemporary audience to see these plays not as theatrical relics but as vibrant contributions to our ongoing dialogue on gender, power, wealth, and class.