THE IMAGINAD PAST IN INGMAR BERGMAN’S THE BEST INTENTIONS

ROCHELLE WRIGHT

Rochelle Wright is Associate Professor of Scandinavian, Comparative Literature, and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she has taught since 1975. She has published extensively on twentieth-century Swedish fiction and translated two novels by the Swedish writer Ivar Lo-Johansson. She is currently writing a book on the images of ethnic outsiders in Scandinavian film.

NEAR THE BEGINNING OF BlLDER (1990; IMAGES, 1994), his recent retrospective commentary on his films, Ingmar Bergman reveals the autobiographical underpinnings of Smultronstället (1957; Wild Strawberries):

I tried to put myself in my father’s place and sought explanations for the bitter quarrels with my mother. I was quite sure I had been an unwanted child, growing out of a cold womb, one whose birth resulted in a crisis both physical and psychological. (17, 20)1

The penultimate scene of the film, where Sara leads Isak Borg to a sunlit bay across which he can glimpse his parents, is characterized as “a desperate attempt to justify myself to mythologically oversized parents who have turned away, an attempt that was doomed to failure” (22). Bergman further states that only many years later was he able to establish contact with his parents as fellow human beings and thus achieve some measure of reconciliation and understanding.

In the final chapter of his autobiography, Laterna Magica (1987; The Magic Lantern, 1988), Bergman describes how, after listening to Bach’s Christmas Oratorio in Hedvig Eleanora Church, he imagines stepping into his former home across the street and thereby into the past. He encounters his mother, Karin, who has been dead for many years, writing in her diary, and bombards her with questions about family relationships:

Why did I live with a never-healing infected sore that went right through my body? … I have no wish to hand out blame. I’m no debt collector. I just want to know why our misery was so terrible behind that brittle social prestige. (284-85)

An arsenal of possible explanations and motivations does nothing to reduce Bergman’s sensation that “I hurtle headlong through the abyss of life” (285). In this dream, his mother does not respond

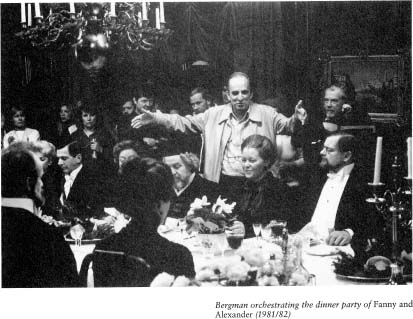

Bergman with the children in the cast of Fanny and Alexander (1981/82) directly to his insistent questioning, she merely deflects it; she is too tired; he should talk to someone else. Then her image dissolves. Back in the present time of the narrative, Bergman recalls that her diaries, found after her death, revealed a woman whose innermost thoughts no one in the family had known.

Examining old photographs in chronological sequence, as he did in the short film Karins ansikte (1986; Karin’s Face)j had allowed Bergman to construct a visual narrative about his mother, but he recognizes that he has not gained access to her inner reality or traced behavior patterns to an ultimate source. In The Magic Lantern he posits a partial explanation for his inherited burden of unhappiness and repression: “[0]ur family were people of good will but with a disastrous heritage of guilty consciences and too great demands made on them” (289). The autobiographical volume ends with a quotation from his mother’s diary, written only a few days after his own birth, that exposes her ambivalence both about her marriage and about her infant son.

Taken together, these passages from Images and The Magic Lantern suggest Bergman’s reasons for writing Den goda viljan (1991; The Best Intentions, 1993), a fictional account of his parents’ early years together, from 1909 until 1918. (In the original Swedish, the title of the last work alludes directly to the lines from The Magic Lantern quoted above; the phrase god vilja may be rendered either ‘good will’ or ‘best intentions’ in English.) Wild Strawberries is hardly the only Bergman film to explore the parent-child relationship. The importance of his own childhood experiences to his development as an artist has been abundantly attested, both by Bergman himself and by critics. In The Best Intentions, however, he attempts to see his parents from another point of view, not as the mythical giants who dominated his childhood, but as complex individuals whose conflicts and struggles were not primarily focused on him. By concluding the narrative in 1918, the year he was born, he avoids the possible distortion of his own memories, in which he himself is the protagonist. He strives for a perspective that in one sense is objective because it is not self-serving, but that nevertheless relies on intuition and empathy. His investigation may also, albeit indirectly, offer him some insight into himself. “Why should I otherwise take so much trouble?” (105), he asks rhetorically.

Bergman’s text is properly considered primarily in the context of a Swedish tradition of autobiographical and historical fiction; it is quite separate from the six-hour, four-part television series of the same title, directed by Denmark’s Bille August, which first aired in Sweden in December 1991. Bergman knew when he wrote The Best Intentions that he would not direct it. Though he states in the prologue that he envisioned Pernilla Östergren (now Pernilla August) and Samuel Frôler as his parents — they were indeed cast in those roles — he granted Bille August complete freedom to make whatever changes and cuts he desired in the manuscript, and he was not involved in the filming process. The published text, in turn, has not been altered to conform to the television series, which itself underwent further transformation. Pared to less than half its original length, a feature-length version of The Best Intentions was submitted in competition at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Palme d’Or and Pernilla August received the award for Best Actress.

The book is thus a separate entity, distinct from any filmed version, even more than is usually the case with a Bergman screenplay; Bergman himself notes in the prologue that he provides much information that cannot possibly be translated into a visual medium, though it may serve to help the actors in their interpretations. In fact, the text is a prose narrative with stretches of dialogue rather than a conventional screenplay. Most of this narrative is composed in the third person, but Bergman also breaks in periodically to speak in what presumably is his own voice, offering comments and interpretations, a feature that is completely absent from the television series and film. This self-reflexive attitude toward the process of creation and the ongoing analysis of the narrator’s role in the selection and presentation of material are an integral part of the narrative and establish The Best Intentions as a metanovel where much of the discussion explicitly revolves around the reliability of the account and its basis or lack thereof in documentary reality. The following observations will focus exclusively on Bergman’s text.

In his prologue to The Best Intentions, Bergman emphasizes its fictional component: “I have drawn on my imagination, added, subtracted, and transposed, but as is often the case with this sort of game, the game has probably become clearer than reality” (i). Later, the text is referred to as “the story or the action or the saga or whatever” (107), and the author periodically reiterates that “this is no chronicle, requiring a strict accounting for reality. It’s not even a document…. I possess fragmentary notes, brief tales, isolated episodes” (105). The most detailed explanation of Bergman’s attitude toward the historical past comes almost exactly in the middle of the narrative:

This account turns arbitrary, main issues into subsidiary issues and vice versa. Sometimes it indulges in huge digressions in the tradition of oral storytelling. Sometimes it wishes to fantasize over fragments that appear out of the dim waters of time. Unreliability on facts, dates, names, and situations is total. That is intentional and logical. The search takes obscure routes. This is neither an open nor a concealed trial of people reduced to silence. Their life in this particular story is illusory, perhaps a semblance of life, but nevertheless more distinct than their actual lives. On the other hand, this story can never describe their innermost truths. It has only its own momentary truth. (135)

The mere fact that Bergman has not felt constrained by his (admittedly limited) knowledge of actual events comes as no surprise to anyone familiar with the allusive and indirect way he has incorporated his own memories and experiences in previous works. What is illuminating, in The Best Intentions as in his entire oeuvre, is the artistic purpose of these transformations, the internal dynamics governing his artistic reconstruction of the past.

The Best Intentions gives an intimate psychological portrait of its protagonists in an effort to show how, despite their love for each other, despite the best of intentions, their relationship does not lead to happiness for either of them. Bergman’s starting point is a conception of character, an interpretation of his parents’ personalities that derives from various sources: to some degree from documentation and specific conversations with them about the early years of their marriage, but also from his own personal knowledge of them in later life, from understanding achieved after their deaths, and, most important, from his own imagination and intuition. He has made little attempt to piece together a verifiable sequence of events. Though he claims to have read his mother’s diary, he seems to have mined it for psychological insight rather than factual information. The narrative he constructs offers a plausible, but not factual, version of their lives that neither justifies nor condemns, but, rather, explains and illustrates. It is an imagined past, a sort of alternative universe, that only partly overlaps with the past of historical record.

A comparison between events and chronology in The Best Intentions and the actual experiences of Bergman’s parents, Karin Àkerblom and Erik Bergman, is possible through an examination of the record they themselves left behind. After the death of both parents, Bergman and his siblings agreed that their private papers would remain in the possession of the youngest child, Margareta. In 1992, only a few months after The Best Intentions appeared, a selection of these documents was published, with additional biographical information and commentary provided by the editor, Birgit Linton-Malmfors, under the title Den duhhla verkligheten. Karin och Erik Bergman i dagböcker och hrev 1907-1936 (A Double Reality. Diaries and Letters of Karin and Erik Bergman, 1907-1936). Included are excerpts from Karin’s private diary, from a family chronicle that she also prepared, from an autobiography composed by Erik for Margareta in 1941 (though she was instructed not to read it until after his death), and from letters, the majority from Erik to Karin or from Karin to other family members, in particular her mother. (Karin seems to have destroyed most of her letters to Erik.) Though the documentary record as presented here is far from complete, it suffices to establish a reliable outline of the period covered in The Best Intentions. There is no reason to suspect the editor of deliberately distorting the facts or of attempting to manipulate the view of Karin and Erik Bergman that the documents convey.

A detailed, point-by-point examination conclusively demonstrates that the fictional narrative and the various factual accounts differ profoundly, even more so than Bergman’s own interpolated commentary indicates. By discussing several specific discrepancies, I will suggest some general principles according to which Bergman recasts and reinvents his material.

The character of Henrik, based on Bergman’s father, Erik, is established early in the narrative, which opens with his refusing his paternal grandfather’s request that he be reconciled with his grandmother on her deathbed (a rebuff that calls to mind Bergman’s own rejection of a similar request from his mother when his father was hospitalized and very ill). In the second scene, Henrik fails an important examination in church history and is unable to find solace from his fiancée, Frida. A visit to his anxious, overprotective mother, who constantly refers to the sacrifices she has made on his behalf, only Increases his guilt. Their scheme to borrow more money from three rich maiden aunts by deceiving them about his academic success Is humiliating and nearly backfires. Henrik’s pride and self-assertiveness are revealed as a façade designed to hide his Insecurity, lack of self-esteem, and separation from meaningful human contact.

In contrast, Anna, drawn on Bergman’s mother, Karin, Is secure in her position as the much-loved only daughter In a large, close-knit, economically privileged family. She is charming and Intelligent, but spoiled, headstrong, and accustomed to getting her own way. The couple meets when Anna’s brother Ernst, a friend of Henrik’s and a fellow student, invites him to dinner at their home. It is Anna who takes the initiative In their relationship, and it is she who fights back with determination when her mother opposes it.

The Best Intentions emphasizes not only the psychological dissimilarities between the protagonists, but also the social and economic disparity in their situations. In actuality, Bergman’s parents were second cousins and met when his father paid a duty call on the Âkerblom family at the time he began studying at Uppsala; Ernst was thirteen years old at the time. The maiden aunts who finance Henrik’s education in The Best Intentions had their correspondents in real life, but they were relatives of Bergman’s mother as well, and it may have been at their estate that his parents first got to know each other well. There is no mention of kinship between the protagonists in the fictional narrative, since such a connection would be contrary to Bergman’s decision to highlight contrasts and differences.

A Double Reality documents the opposition of Karin’s mother to her choice of husband, though little specific Information is offered. The battle of wills between mother and daughter becomes a major theme in The Best Intentions, where the mother Intervenes at two crucial junctures: first, by using her knowledge of the engagement to Frida to blackmail Henrik into breaking off with Anna, and, much later, by intercepting and burning a letter from Anna to Henrik in which she reaches out to reestablish their bond. In the fictional narrative, the couple Is separated for two years; not only does Anna refuse all contact with Henrik during this time, but she also becomes ill with tuberculosis and goes abroad to receive care at a sanatorium, and then embarks on a tour of Italy with her mother. Her father’s death during their absence prompts her mother to confess to having burned the letter to Henrik against the wishes of her husband. Upon returning to Sweden Anna seeks out Henrik and they begin planning their life together.

The actual progress of the relationship between Bergman’s parents was far less dramatic. Though their courtship was not without difficult moments, there Is no evidence of any cessation of contact, and the frequent physical separations came about because Karin was training as a nurse in Göteborg and Stockholm while Erik continued his studies In Uppsala. Karin did become ill, but her time abroad consisted of an eighteen-week trip taken with her mother and brother. Her father lived until 1919, after Bergman was born.

These examples should suffice to illustrate how Bergman departs from historical fact In order to create tension and drama. The interpretation of his parents’ characters and personalities appears to be consistent with the documentary evidence, but many, if not most, of the events described In The Best Intentions are fictional, the product of Bergman’s imagination. Sometimes Bergman explicitly states that this Is the case, for instance with regard to the episode he presents as a turning point In the relationship between Anna and Henrik, an explosive quarrel In the chapel near their future home. This scene Is an extrapolation, an imagined scenario, one of many possible scenarios.

It’s always hard to trace the real reason for any conflict…. One can imagine quite a number of alternatives, both random and fundamental. Go ahead, you can browse and speculate: this Is a party game. (175)

If we construe Bergman’s exhortation to “go ahead” as being addressed to the reader as well as himself, it follows that we are included in the author’s imaginative game: we are encouraged to question his interpretation of the argument’s significance or to envision another version of events entirely. In her essay “The Director as Writer: Some Observations on Ingmar Bergman’s Den goda viljan” Louise Vinge points out that Bergman’s technique of introducing the reader into his creative process is characteristic of a postmodern work. He sets the stage, but the performance continues in our mind’s eye.’ Bergman thus relinquishes control of his own artistic production.

In a fictional account, obviously, Bergman is free to alter facts to suit his own purposes and to position the reader not only as spectator but as codirector. There the matter would rest, were it not that he periodically calls attention to the documentary sources of the narrative, sometimes in a manner that seems designed to create confusion about what is historical fact and what is not. The names of the characters are a case in point. The protagonists of The Best Intentions are called Anna and Henrik, but early in the narrative Bergman punctures this fictional disguise. After a long descriptive passage, he sums up as follows:

That’s what she looks like —Anna, my mother, whose name was really Karin. I neither want to nor am able to explain why I have this need to mix up and change names: my father’s name was Erik, and my maternal grandmother’s was Anna. Oh, well, perhaps it’s all part of the game — and a game it is. (18)

Bergman’s comment implies that Anna and Henrik both are and are not fictional characters, and both are and are not to be identified with Bergman’s own parents. That the fictional narrative switches the names of real-life mother and grandmother — Karin becomes Anna, Anna becomes Karin — at first seems perversely designed merely to create confusion, but it also suggests that in Bergman’s imagination, their identities merge. The choice of the name Henrik for a prickly, self-involved, romantic young man tormented by self-doubt should be familiar to students of Bergman’s early films. It is interesting that in his subsequent autobiographical narrative, Söndagsbarn (1992; Sunday’s Children, 1994), in which his eight-year-old alter ego plays a central role, Bergman calls his parents by their actual names. Though this novel is also a fictional reconstruction, it draws in part on Bergman’s own personal memories rather than his recollection of others’ versions of the past, as was the case in The Best Intentions. Perhaps his own participation in the action of the narrative and his consequent (relative) lack of distance to the material led him to more closely identify the fictional characters with their real-life counterparts.4

The deliberate blurring of the boundaries between fact and fiction established by Bergman’s “name game” plays an important role throughout The Best Intentions. For instance, the text states, “My parents were married on Friday, March fifteenth, 1913” (184). Clearly, Bergman can marry off the fictional characters Anna and Henrik on whatever day he pleases, but the text appears to refer to Bergman’s real-life parents, Karin and Erik, since we assume the first-person narrator to be Bergman himself. The actual wedding date of the elder Bergmans was Sept. 19,1913; March 15 was the day their engagement was formalized. A slip, a memory lapse? This explanation cannot account for the fact that Bergman (or, rather, strictly speaking, the first-person narrator) notes that though no wedding picture has survived, he has before him a wedding invitation — which, one assumes, would state the date on which the nuptials were solemnized. Either Bergman is referring to an imaginary document — a possibility that is not as fanciful as it may seem at first —- or he chooses, for reasons known only to him, to mislead the reader deliberately. Perhaps by blurring the distinctions between the fictional Anna and Henrik and the historical Karin and Erik, Bergman is suggesting that our perceptions of others, our responses to them, and our interpretations of their behavior ultimately are based on imagined constructs that we ourselves impose. As Louise Vinge states, “Illusion and reality seem to have fused in the author’s mind through the creative work” (292).

In other instances, too, it is difficult to establish whether Bergman is referring to actual documents, letters, and photographs, or whether these objects should be construed as belonging exclusively to the fictional narrative. Letters attributed to Anna or Henrik in The Best Intentions appear to have been composed by Bergman rather than excerpted from authentic letters exchanged between his parents, and are presented as part of the imagined universe. References to photographs and visual images, however, are often ambivalent or deceptive. When Bergman begins a passage with the words “The picture [or image] shows… it cannot always be determined whether he is describing a photograph, real or imagined, or imagining the completed film, or both. A particularly complex example of this confusion occurs in The Best Intentions with regard to a portrait of the Âkerbloms taken while Henrik is visiting the family. Bergman assures the reader that this photograph actually exists, an impression he reinforces by meticulous specification of what it depicts and by mention of examining it through a Magnifying glass. At the same time he casts doubt on its authenticity by stating that though the photograph probably dates from 1912, he places it in 1909 in the fictional narrative because “it fits better into this context” (76). He describes Henrik and Ernst as both wearing student caps in the photograph and states that it is “quite clear” that Henrik is present in the capacity of friend of Ernst rather than suitor of Anna. This strains credulity when applied to the real-life situation, for Ernst had not taken his matriculation examinations in 1912, let alone 1909, and furthermore was eight years younger than Bergman’s father. But Bergman continues:

Go into the photograph and recreate the following seconds and minutes! Go into the photograph as you want to so badly! Why you want to so badly is hard to make out. Maybe it’s to provide some somewhat tardy redress to that gangling young man at Ernst’s side. (77)

The phrase “Go into the photograph” may be read in several different ways. If one posits the existence of an actual photograph, this invitation or command may simply be Bergman giving himself permission or urging himself to imagine and describe the circumstances under which it was taken. This interpretation is supported by Bergman’s explanation in the prologue to The Best Intentions that he inherited a number of photograph albums after the death of his parents and that these images fascinated him. More generally, however, “going into” the picture may be construed as a metaphor for the visual imagination. The reference in the quotation to “the following seconds and minutes” may allude to Bergman’s chosen medium of film, in which still images are connected in a narrative sequence in time, and more specifically to the film of The Best Intentions that he imagines or envisions. The prologue further states:

I go into the photographs and touch the people in them, the ones I remember and the ones I know nothing about. It is almost more fun than old silent films that have lost their explanatory texts. I invent patterns of my own. (i)

In The Best Intentions, Bergman demonstrates that the imagined past has its own validity, coherence, and autonomy, whatever its documentary basis. In fact, since the actual historical past can never be fully reconstructed, the imagined past is all that is left — to him, and to us.

Notes

Works Cited

Ingmar Bergman. The Best Intentions. Trans. Joan Täte. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1993.

——. Bilder. Stockholm: Norstedts, 1990.

——. Den goda viljan. Stockholm: Norstedts, 1991.

——. Images: My Life in Film. Trans. Marianne Ruuth. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1992.

——. Laterna magica. Stockholm: Norstedts, 1987.

——. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. Trans. Joan Täte. New York: Penguin Books, 1988.

——. Sunday’s Children. Trans. Joan Täte. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1994.

——. Söndagsbarn. Stockholm: Norstedts, 1993.

Birgit Linton-Malmfors, ed. Den dubbla verkligheten. Karin och Erik Bergman i dagböcker och brev 1907-1936. Stockholm: Carlssons, 1992.

Louise Vinge. “The Director as Writer: Some Observations on Ingmar Bergman’s Den goda viljan,” in A Century of Swedish Narrative: Essays in Honour of Karin Petherick. Ed. Sarah Death and Helena Forsâs-Scott. Norwich, U.K.: Norvik Press, 1994.

1 Here and elsewhere, page references are to the published English translations of Bergman’s works, though I have studied them in the original Swedish.

2 A Century of Swedish Narrative, 286.

3 Ibid., 285. Vinge analyzes the ambiguous way Bergman uses the Swedish word forestalling, which may refer both to the imagination and to stage performance, and offers an enlightening interpretation of how the quarrel scene comments on “the relation between illusionary art and reality” (291) in Bergman’s text.

4 Bergman’s greater personal involvement with the subject matter of the second novel is also suggested by his selection of his own son Daniel, rather than an outsider, to direct the subsequent film.