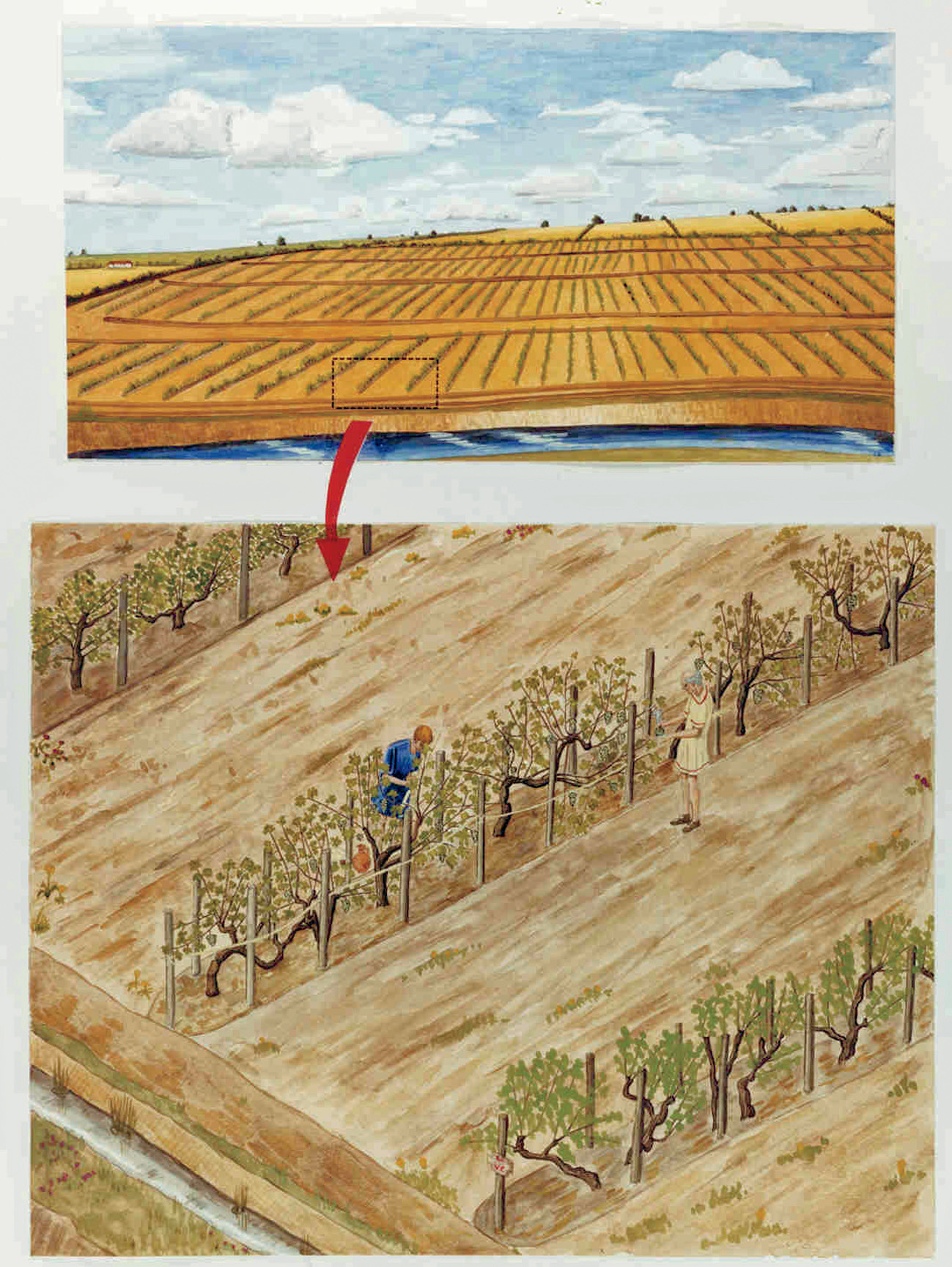

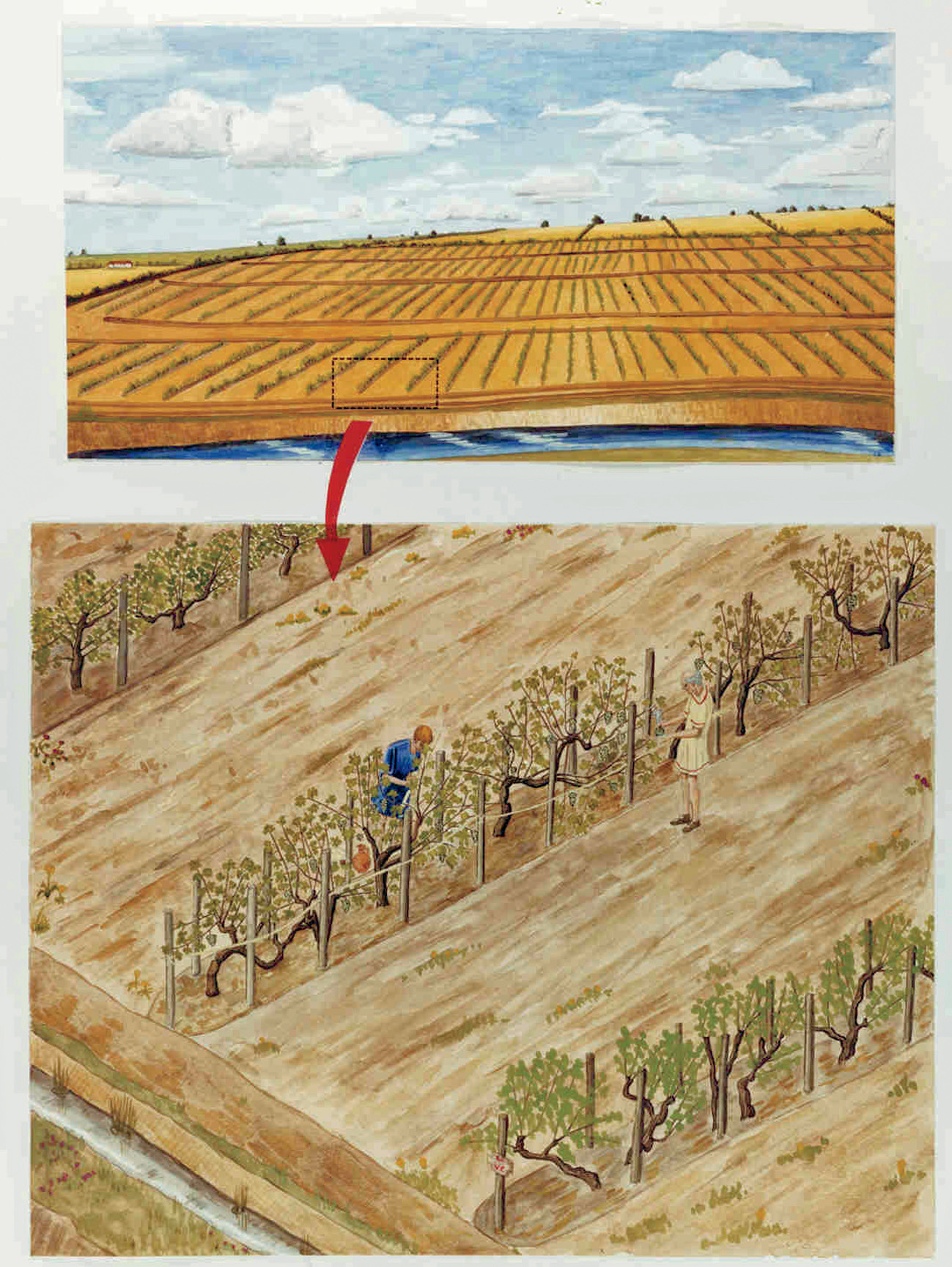

How the Roman vineyard at Wollaston could well have looked in the second century AD. MUSEUM OF LONDON ARCHAEOLOGY

THE ROOTS OF ENGLISH WINE DIG BACK TO ROMAN TIMES

Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road . . .

G.K. CHESTERTON’S HAPPY EVOCATION OF WHAT might be the earliest example of UK wine tourism is one of my favourite poems. Unfortunately for this book, it is far more likely that his early over-imbiber was going in search of ale or cider rather than wine. But wine was certainly known, if not actually made, in Britain before Julius Caesar’s tentative incursion in 55 BC. And, with the local product much boosted by imports from often warmer, sunnier locations, it has carried on satisfying UK palates ever since.

There have, not unexpectedly, been hiccups in the home-made supply. The immediate aftermath of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and the coldest part of the ‘little ice age’ that soon followed are those most frequently quoted, though not entirely correctly – wine production may have diminished, but it didn’t stop in either period. A serious slump came in the nineteenth century, but the real hiatus occurred much more recently, as the two world wars and their repercussions largely put paid to wine grape-growing for three decades. Now, we’re in a time of global warming, and with it – though certainly not only because of it – the English wine revival is resplendent.

The earliest vines in British soil

When were grapes first grown for wine in the British Isles? In the absence of firm evidence, it is impossible to be definitive, and the fact that vine pollen dating back some 400,000 years has been found in Essex in no way means that wine was made by Britain’s earliest hominids. Worldwide, current evidence points to the first pure grape wine being made far to the east, in Georgia, in the sixth millennium BC, although fermented beverages including grapes but not made solely of them are known to have been made in China a little earlier. Much more realistically, argument continues over whether in the first century AD Tacitus was correct in saying that the vine couldn’t flourish in Britain. However, from the latter part of the third century, Britain was one of several Roman provinces where the inhabitants were, by edict of Emperor Probus, specifically permitted to cultivate vineyards and make wine. There is every possibility that they did so, probably even before they were given that formal authorization.

The best evidence comes from the gravel extraction site of Wollaston in the Nene Valley, Northamptonshire, just south of Wellingborough and close to the Roman town of Irchester. Archaeologists worked for five years in the 1990s alongside a 3-kilometre stretch of a major Roman road. They found a large area – 7.5 hectares, appreciably bigger than the average size of a modern English vineyard – where narrow, steep-sided parallel trenches had been cut, filled with topsoil or manure and plants set in them 1.5 metres apart, with stakes for support. Pottery from the trenches suggested a second to third century AD date for the site.

Was it a vineyard? ‘There can be little doubt,’ reported the excavation team, which was led by Ian Meadows, then head of Northamptonshire Archaeology. Samples of pollen from the trenches and surrounding drainage ditch indicated that vines grew there, alongside grasses and weeds of cultivation. Also, the widely spaced trenches matched the shape of those in vineyards discovered in other parts of the Roman empire, notably France, and replicated the continental vine-cultivation practice of pastinatio, as described by contemporary natural historians. This was, said the Wollaston archaeologists, ‘an important indication of Roman agricultural innovation in Britain’.

How the Roman vineyard at Wollaston could well have looked in the second century AD. MUSEUM OF LONDON ARCHAEOLOGY

Overall, Meadows and his colleagues estimated, the vineyard would have covered some 11 hectares; with several other sites identified in the vicinity, this indicated that the Nene Valley was a major wine-producing area. ‘Wine produced on this scale would have been a significant cash crop, and it is unlikely that it was entirely consumed locally,’ they added, arguing that the discovery implies that wine was far more important in Roman Britain than anyone had previously believed. ‘Wine probably never supplanted beer as the “national” drink in Roman Britain, but the new evidence suggests that viticulture may have had a greater impact than previously envisaged.’

Academic accounts in the journal Antiquity apart, the findings were also less formally reported in the magazine Current Archaeology, under the headline ‘Wollaston: The Nene Valley, a British Moselle?’ The vineyard, wrote Meadows in that article, ‘represented a major capital investment by the original owner(s)’. He continued: ‘Over six kilometres of trench were dug and, on the basis of plant spacing at every 1.5m, there were at least 4000 separate vines. This would allow for the production of about 15,000 bottles of white wine each year.’ When he talks to a non-specialist audience, he likens that number of bottles to the volume of liquid carried by a petrol delivery tanker. The comparison helps to indicate the scale of what he emphasizes was ‘a major commodity, produced in vast amounts’.

One of the Wollaston vineyard trenches, showing the holes for stakes and vine roots. MUSEUM OF LONDON ARCHAEOLOGY

One possible point of concern is that no specific vine-growing tools have been found at the Nene Valley sites. Many of those used, though, would have been common to other types of farming, and Meadows suggests he and his colleagues perhaps ‘missed a trick’ by concentrating more on them than on considering the containers in which the wine travelled away from its source. These were probably barrels, as no local styles of amphora have been found. Given the fragility of wood, the barrels themselves were unlikely to survive, but what of the tools of the coopers who made them?

Another unknown is where the grapes were processed, although this was possibly done in a nearby villa or at Irchester. And there must have been a market for those thousands of litres of wine, so what is the answer to the most intriguing question of all: who drank it? The enthusiasm for wine in imperial Rome is legendary, with some historians estimating that everyone, from the emperor’s entourage to slaves, consumed approximately a bottle a day. Away from their homeland, Roman soldiers were granted a regular allowance of what is generally thought to have been wine, and the banqueting upper classes were happy imbibers, as evidenced from wall paintings in villas in all parts of the empire. Given the scale of production at Wollaston alone, there were surely indigenous British drinkers too. And further evidence suggests that the local supply was by no means sufficient.

An altar, made of Yorkshire millstone grit and dating to AD 237, was found a century ago during excavations in Bordeaux. The inscription identifies its owner, Marcus Aurelius Lunaris, as a high-ranking priest in the Roman colonies of Lincoln and York. He had dedicated the altar to the French city’s protective Roman goddess Tutela Boudiga before he set off from York on what is thought to have been a regular journey across the water. Scholars believe that the wealthy Lunaris was likely to have been a merchant as well as a priest and, given his destination, could well have been involved in the wine trade. Was he alone in that role? Most probably not.

The Nene Valley vine-growing area has recently been confirmed as extending to the north of Wellingborough as well as around Wollaston to the south, but these were not the only vineyards established in Roman Britain. While archaeologists have to take care over interpreting the plentiful finds of grape pips as evidence for the existence of others – most pips more probably came from imported table grapes – vines appear to have been planted in various parts of southern England and as far north as Lincolnshire. Ian Meadows argues that, once the Romano-British farmers had discovered that their vines would grow happily without using the elaborate pastinatio system, many more would have planted them. Places where cuttings were pushed directly into the ground, with small stakes to support them, don’t register even in sophisticated archaeological surveys, but they surely existed in some profusion. Meadows will continue to be among those aiming to find them. After all, he says, for someone in his profession who enjoys a glass of wine, this is an unusually rewarding research area.

After the Romans, the wine-drinking monks

What happened before the Romans? As I write, earlier evidence of vine cultivation or winemaking has yet to be found in Britain. However, wine was drunk by the Belgic tribes who immediately preceded the Romans in southern and eastern England. Maybe they didn’t make their own, but there is little doubt that they imported it: amphorae and even a silver wine cup have been found in high-status graves.

And after the Romans? Despite the ale-swilling preferences of the nordic and germanic invaders, wine was a crucial element in Anglo-Saxon Britain’s developing Christian religious culture, among followers of both the local Celtic and the imported Roman rites. Monastic communities existed in various UK locations from the early fifth century onwards, almost immediately after the Romans’ departure, and they needed to be self-sufficient in wine as well as food. Hence in 731 Bede noted at the very beginning of his Ecclesiastical History of England that the country ‘produces vines in some places’. It would be risky indeed to hazard a guess as to what varieties these vines were, and the quality of the drink made from their grapes, but a tradition had been established, which today is manifested in England’s world-beating sparkling wines.

The importance of wine in England’s religious communities – though rather later than the Saxon monarchs’ vineyard gifts – is shown by these early fourteenth-century English miniatures, from the Queen Mary Psalter and the ‘Welles Apocalypse’ by Peter of Peckham. BRITISH LIBRARY

Continuing post-Roman viticulture is confirmed, for example, by King Alfred’s introduction of a law ordering compensation be paid by any man who damaged another’s vine; by the decision of Alfred’s great grandson, King Eadwig, to grant a vineyard in Somerset to Glastonbury Abbey; and by another royal donation of a Somerset vineyard, at Watchet, this time from King Edgar to Abingdon Abbey. There is even an argument from eighteenth-century antiquary Joseph Strutt that the Saxons called October the ‘Wyn Moneth’, to mark the importance of the grape harvest.

Move on to the late eleventh century and Domesday Book, William I’s detailed inventory of his newly conquered country, has forty-two definite records of vineyards, more of them owned by aristocrats than by monasteries. Remarkably, there are none listed in what are present-day Hampshire or East or West Sussex, and barely a handful in Kent and Surrey – the counties that today have easily the largest concentration of English vineyards. Was Domesday accurate, or were its surveyors so influenced by the excellence of those counties’ liquor that they neglected their recording duties? Whichever, English vineyards multiplied and their product was good: ‘The wine has in it no unpleasant tartness or eagerness, and is little inferior to the French in its sweetness,’ wrote William of Malmesbury around 1150. Gloucestershire, he contended, was the best county, both for the fertility of the vineyards and the sweetness of their grapes; vines were grown in the open without sheltering walls and were trained up poles. The taste then was clearly for sweet wines.

Royal involvement

English wine was not simply the drink of kings and of many of their subjects. The royals also made it – or at least they owned vineyards. Henry II had established one in the grounds of Windsor Castle by the mid-twelfth century and it flourished, producing more wine than the royal household needed and selling on the excess. The site was still recorded as ‘vineyard’ on nineteenth-century plans and, happily, that historic link has been revived, with the planting in 2011 of chardonnay, pinot noir and pinot meunier vines in Windsor Great Park. The first vintage of commercial sparkling wine, from 2013, sold out immediately on its release, in September 2016. The Duke of Edinburgh supported the venture, which was the initiative of Tony Laithwaite, the man behind the biggest mail-order/ online wine club organization in the UK, who just happened to spend his childhood in Windsor and to open his first wine shop in the town.

STEVEN MORRIS/LAITHWAITE’S WINE

But didn’t English wine largely disappear at the very time Henry planted his vineyard? His wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, had brought into English royal hands the vast wine-producing lands of Bordeaux. So why, the argument often runs, didn’t imports from France meet all the kingdom’s needs? It seems not. Was it patriotism, or convenience, or simply that English and French wines appealed to different tastes? Whether for one of these reasons or for some other, vines continued to be planted in English soil, grapes harvested and wine made and drunk in quantity at many levels of society.

All this was clearly commonplace in those post- Conquest centuries, with the production tasks involved illustrated in many surviving sources: manuscript illustrations, carvings in churches and cathedrals, monastic records and a wealth of other documents. Known vineyards include one planted at Beaulieu Abbey in Hampshire by Cistercian monks in the thirteenth century (vine-growing returned here in the twentieth century); another was a feature in the kitchen garden of a fourteenth-century Bishop of Ely at his London house, in Holborn. In southern England there is hardly a town without at least one ‘vine’ street name or a county without a cabinetful of records relating to vineyards and local wine production.

Present replacement of vines past: the twenty-first-century Windsor Great Park Vineyard. STEVEN MORRIS/LAITHWAITE’S WINE

Drinking wine, too, was a common – and sometimes over-indulged – pleasure, one not confined to the noble, privileged and religious alone. A number of the fourteenth-century pilgrims in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales were serious imbibers: the Summoner ‘drank strong blood red wine untill dizzy’, while the description of the Franklin noted that ‘no man had his cellars better stocked with wine’. Chaucer, whose father and grandfather were vintners, was himself granted a generous daily allowance of wine – a pitcher or a gallon according to which source you choose – by Edward III, whom he served in a variety of roles.

But the poet’s Pardoner fulminated against all such indulgence:

A lecherous thing is wine . . .

Oh drunken man, disfigured is your face,

Sour is your breath, foul are you to embrace . . .

Now keep you from the white and from the red.

Modern reproduction of the bird pecking grapes carved on a fourteenth-century misericord at Lincoln Cathedral. OAKAPPLE DESIGNS LTD

Perhaps he had good reason to preach that message, and not only because of the dangers of intoxication. While the pilgrims’ wines, it seems, were often red and maybe imported, pity many of those men and women who drank the medieval English product. The story that follows may be apocryphal, but it’s too good not to share. When King John visited the monks at Beaulieu he took one sip of their wine and ordered: ‘Send ships forthwith to fetch some good French wine.’ That could have indicated the usual standard of monastic wine, or perhaps the royal beaker was filled from a bad vintage – something far from unknown, even in that generally mild time. So much for modern climate change: from the ninth to the late thirteenth centuries, England appears to have had warmer summers, and also more rain, than in the mid-twentieth century.

On, then, to a chillier period for English wine producers – though one caused only partly by a change in the weather. Henry VIII’s decision in 1536 to dissolve the monasteries of his kingdom most probably had much less effect on wine grape-growing than many commentators have assumed; after all, the wine-drinking nobles who took over the monastic estates were handed productive vineyards, sparing them the effort and time to establish vines from scratch. Also, many of the senior clerics themselves moved from monasteries to new religious positions in more secular surroundings – and they weren’t banned from making their own wine.

Men picking grapes on a fourteenth-century misericord in Gloucester Cathedral. WWW.MISERICORDS.CO.UK

But climate did become something of an issue. The ‘little ice age’, which peaked in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, didn’t totally stop vines flourishing, but it made producing good wine rather more difficult. Yet in his 1586 history Britannia, William Camden offered an alternative reason for the sixteenth-century decline. He blamed the barrenness of once-fruitful land much more on ‘the sloth of the inhabitants than the indisposition of the climate’. Hugh Barty-King, a painstaking historian of English wine, supports Camden’s argument: ‘It seems to me the most sensible observation ever made on English viticulture: it remained as true throughout the following centuries as it was when it was made.’ Why? Because, as Barty-King sensibly reasons, while decent wines can be made easily in hotter places, success in borderline climates such as England’s requires more work, closer attention to the vines and precise application of broad technical knowledge.

The right places, the right people

The detail of successful modern wine production in England will follow in later chapters, but already in the thirteenth century there was good counsel to be had on the best choice of sites for vineyards. By the end of the sixteenth century and on into the seventeenth, advice on both vineyard location and vine variety was proliferating. Often it was along rather similar lines to that offered hundreds of years later, suggesting planting the same vines as those that flourished along the Rhine or around Paris and siting them on warm, sunny, well-drained hillsides.

Largely, if not uniquely, the growing of vines appears to have been the province of the upper classes; there is a dearth of information on whether lesser mortals copied them. By far the biggest viticultural project in Britain at this time was Lord Salisbury’s, at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. In 1611 20,000 vines were brought there from France, shortly followed by another 10,000. The vineyard flourished for three decades at least. Visiting in 1643, the diarist John Evelyn described the garden and vineyard as ‘the most considerable rarity besides the house’. However, things seem to have gone somewhat awry for a while subsequently; in 1661, Samuel Pepys took an after-dinner stroll at Hatfield: ‘I walked all alone to the Vineyard which is now a very beautiful place again.’ Neither writer mentioned the Hatfield House wine. Pepys did have a happy experience of English wine when in 1667 he visited Admiral Sir William Batten: ‘And there, for joy, he did give the company . . . a bottle or two of his own last year’s wine, growing at Walthamstow.’ The guests’ verdict was that it was better than any foreign wine they had encountered.

Samuel pepys by John Hayls

Evelyn had a rather closer involvement with seventeenth-century English wine, despite his dismissal of one example he encountered as ‘good for little’. After meeting John Rose, gardener to King Charles II, and talking to him at length about vines, the diarist was persuaded to write the preface to Rose’s The English Vineyard Vindicated, published in 1666. (Three years later it was combined in a single binding with Evelyn’s translation into English of a more general horticultural work, The French Gardiner; included too was Evelyn’s own detailed account of winemaking, The Vintage.) Rose dedicated his short work to his employer, declaring that he knew that the king ‘can have no great opinion of our English Wines’. But their defects were due neither to the climate nor to the work-shy attitude of those who tended the vines, he insisted. Follow his directions on choice of soil and situation, grape variety and cultivation practice, and ‘that precious liquor may haply once againe recover its just estimation’.

In 1670 another gardener to nobility, Will Hughes, expanded his advice to would-be vine-growers in an enlarged edition of his work The Compleat Vineyard: or, An Excellent way for the Planting of Vines, According to the German & French manner, and long practised in England. Hughes, too, argued that ‘excellent good wine’ could be produced in England. Like John Rose, both he and Samuel Hartlib, another advocate of the potential of English wine, whose The Compleat Husband-man had been published in 1659, set down specific rules on vineyard site location and named the best grape varieties for successful cultivation. Hartlib and Hughes favoured the Rhenish-grape and the parsley vine (the latter more for show and rarity than profit, commented Hughes); Hartlib also recommended the Paris-grape and the small muskadell, while on Hughes’s list came the frantinick and three varieties of muscadine, two white and a red; Rose suggested considerably more varieties.

For much of this historical information I’m indebted to Hugh Barty-King, a prolific writer on a myriad of subjects whose research skills were indefatigable. His A Tradition of English Wine was published in 1977, but there is one chapter, ‘Viticulture Becomes Scientific and Commercial’, that comes remarkably close to describing the situation today – except that it recounts what happened in the years 1700 to 1800. Time and again in those thirty-four pages appear arguments that current supporters of the home-grown product still too often have to refute: that making wine in England is an eccentric activity; that English wine has little appeal for many drinkers; that growing vines ‘to any tolerable perfection’ is ‘altogether impracticable’; that drinkers lack the enthusiasm to try something different; that to sell English wine its origin must be hidden from potential buyers until they have tasted it. Some of the eighteenth-century facts anticipate the present, too: that even the wealthiest estate owners can find costs so high they need to seek loans to continue producing wine; that some English estates employ French winemakers, or the sons (and now daughters too) of English estate owners go to France to learn viticultural skills; that successful producers play a valuable role in promoting their country. Certainly, there were challenges, but increasingly palatable wine was being made.

Growth on a larger scale

The upshot of the emphasis on more professional wine grape-growing in the eighteenth century was that large vineyards were successfully established. One was close to Godalming in Surrey, on the Westbrook estate of James Oglethorpe, MP for Haslemere, where two long south-facing terraces were constructed and planted with vines in the 1720s. Oglethorpe’s hospitality was renowned; his wine flowed generously at the many soirées and political gatherings he organized, and his guests feasted on snails fattened on the leaves of his vines. The vineyard survived for a hundred years, still mentioned in 1823 in sale particulars for the estate.

Charles Hamilton shortly before he began his Painshill Park venture, by Antonio David. PAINSHILL PARK TRUST

A little shorter-lived but better known was another initiative in Surrey, near Cobham, close to today’s junction of the M25 and the A3. In 1738 the Honourable Charles Hamilton, youngest son of the Duke of Abercorn, began leasing land on the Painshill estate, and set to work transforming it into an extravagant 120-hectare private pleasure ground, enhanced by a multitude of follies. But the vineyard he created on a south-facing slope rolling down to a large artificial lake was no romantic fancy. It was a serious project.

In 1748 Hamilton employed a French vigneron to care for his vines and oversee the whole estate. There was a problem, however. The recruit, David Geneste, came from a family who had grown grapes in Bordeaux for generations, but, after a good number of years as a refugee in England (he was a Huguenot), he had forgotten much of what he had learned as a boy. His solution was an appeal to his sister, still in France, which brought the information he needed and also essential tools, and the vineyard flourished.

The first Painshill wines were reds, but they were harsh and unfit to drink, so Hamilton turned to white and ‘to my great amazement my wine had a finer flavour than the best champaign I ever tasted’. More than simply having the flavour of champagne, the two wines – one clear white, the other a delicate bronze pink – also bubbled. ‘Both of them sparkled and creamed in the glass,’ said a contemporary report repeating their maker’s words. How Hamilton achieved that effect is not recorded, but by the mid-1750s the selection of vines at Painshill had grown to include varieties originating from Burgundy – the tender auvergnat, possibly related to pinot noir, and the hardier miller, often identified now as pinot meunier. These could perhaps have been ancestors of the grapes that go into today’s English sparkling wine. But no fuss was made about the origin of the wine. Hamilton was well aware of the prejudice towards ‘any thing of English growth’ and deemed it ‘most prudent not to declare’ where his wine came from until it had been tasted and approved.

That strategy worked. In a letter to his sister, David Geneste wrote that his employer was selling the excellent white wine from the 1753 harvest for sixty guineas (£63) a barrel, and local customers bought Painshill wines at half a guinea (52.5p) a bottle. However, despite the respect the wine gained and the income it produced, Hamilton’s extravagant park emptied even its wealthy creator’s deep pockets. He failed to meet interest payments on a loan and in 1773 was forced to sell.

Hamilton’s legacy was important, as Barty-King acknowledges: ‘Thrice married, he was one of the most colourful men of his time and certainly the most enterprising viticulturist.’ He had set new standards that others were to follow. And in happy remembrance of the park’s former owner, the charitable Painshill Park Trust in 1992–93 replanted the vineyard, albeit at half its original size, as part of its overall restoration of the estate.

The prejudice against English wine – and an increasing concentration on glasshouse-grown table grapes – failed to halt its production. While it seems that figures for the quantities produced at Westbrook and Painshill have not survived, there was certainly more wine than the gentlemen growers needed, with the surplus finding a market in the inns of surrounding Surrey villages. These vineyards may well have been the biggest yet in Britain, but there are records of plenty more eighteenth-century locations around London, in Kent, Hampshire, the West Country, East Anglia and even Shropshire where vines were grown. A particularly large one on the edge of Bath produced 66 hogsheads in good years, if the figure quoted by Hugh Barty-King is to be believed. In twenty-first-century terms, that equates to close to 13,500 litres or nearly 18,000 modern-day bottles – a huge figure. (Converting historic measures for modern comparison is a numerical minefield, so I’ve used the commonest estimates: before 1824 a hogshead of wine held 43 to 46 imperial gallons and after that date the volume was 52.5.)

Even more impressive, according to Barty-King – whose ‘reliable’ source was again H.M. Tod’s Vine-growing in England (1911) – was the 60-pipe yield in 1763 of a vineyard established by the tenth Duke of Norfolk at Arundel Castle in Sussex. A pipe had twice the capacity of a hogshead, so the duke’s wine could have filled around 32,000 75-centilitre bottles. Yet contemporary plans indicate that his vineyard covered barely a hectare, and there were no others in the castle grounds. Something must be wrong here, for so much wine to come from so small an area. Present-day English yields from a hectare of vineyard are far, far lower, averaging around 2,700 bottles. They surely wouldn’t have been almost twelve times that in the eighteenth century.

A little more investigation indicates that there seems to have been a misinterpretation of the original information, which can be traced back to a weighty collection of papers on agriculture, commerce, arts and manufactures entitled Museum rusticum et commerciale and published from 1764 onwards by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers & Commerce. What was reported there, according to two accounts published not long afterwards, puts a subtly different slant on the matter. The duke’s cellar was referred to as containing (my emphasis) in 1763 ‘sixty pipes of excellent Burgundy, the produce of a vineyard attached to the castle’. Arundel Castle wine, but more likely the product of many years’ harvests, not of a single one.

The duty argument: should French wine face a high import levy?

Statistics apart, the cross-Channel quality comparison is appropriate. English wine needed to be as good as Burgundy’s, because, as the nineteenth century dawned and Napoleon blockaded Britain, the French product became much harder to obtain and increasingly expensive. This was a time of much yo-yoing of import duty on wine, French in particular, with an inevitable impact on the popularity of home-produced bottles. In 1787 Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, clearly not a fan of English wine, had halved the import duty per gallon (450 centilitres approximately, or six bottles) from eight shillings (40p) to four shillings. By encouraging French imports, that reduction would, he told the House of Commons, ‘supplant only an useless and pernicious manufacture in this country’. Sure enough, sales of French wine soared.

It didn’t take long for the low-duty policy to be reversed. Successive increases more than tripled the levy by 1807, and a further hike in 1813 brought it to only a few pennies less than £1. That last rise was intended to boost, if in only a small way, the British government’s wartime finances. It also helped the home vine-growers, as Benjamin Oliveira, MP for Pontefract and a determined opponent of oppressive wine import duties, told the Commons in 1856: ‘The British wine trade has grown up in a comparatively short period, in consequence of the prohibitory duty upon foreign wines, and is at this present time a very thriving and increasing branch of commerce.’

Although the duty had decreased from the 1813 peak, even at the then-current 5s 9d, he argued, a reduction would encourage wine drinking at the expense of spirit drinking and the ‘crime and misery’ linked to the latter. It would also bring an overall higher revenue, an argument that continues to be made today as the wine trade in the UK rails against the present high excise duty levels that apply to both home-produced and imported wine.

Oliveira’s failure to bring about change seemingly didn’t deter those who were determined to continue drinking fine foreign wine, even if they had to pay more heavily than they wished for their claret. Yet there were others who argued the local case – that it was an Englishman’s patriotic duty to produce his own wine and that he could make a very decent one, perhaps one even more palatable than those pricey imports. Once again, the lessons learned from earlier centuries had to be drummed into the heads of those who had land to plant and money to invest, to revive a broad enthusiasm for English wine. And, tellingly, there were the first suggestions of experimenting with imported American vines as a better bet to survive rot and disease.

Just a few took up the challenge of planting on a large scale, with the most ambitious scheme instigated by a Scotsman, on land in Wales. Castell Coch, close to Cardiff, was the location chosen by John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, third Marquess of Bute.

Crichton-Stuart, whose family interest in Cardiff docks and coal made him one of the wealthiest men in Britain, loved all things medieval. He restored both Castell Coch and Cardiff Castle to an elaborated version of their thirteenth-century glories – so why not add a vineyard at the former, to follow the tradition of the nobles and monks of the period? The chosen site beneath the castle walls was actually quite suitable for vines: a protected south-facing slope with limestone bedrock.

After an extended tour of French vineyards at harvest time in 1874, Lord Bute’s head gardener, Andrew Pettigrew, returned with two main grape variety recommendations, gamay noir (finally, a grape which is known today!) and miel blanc. The first 2,000 vines were scarcely planted on the 1.2-hectare site before the enterprise was ridiculed on a national scale, most notably in Punch magazine. If wine was ever produced from such an unsuitable location, the magazine predicted cynically, it would take four men to drink it – the actual consumer, two others to hold him down and the fourth to force the liquid down his throat.

The early harvests were poor, in quantity at least, the first producing only 240 bottles. But by 1887 – a particularly good year for a place where vintage variation, largely due to poor summers, was extreme – the output had risen to around 3,000 bottles, all white. By the mid-1890s, production of both white and red wine in good vintages reached 12,000 bottles. These are realistic production figures, especially as over its productive lifetime (until the outbreak of the First World War) the original Castell Coch vineyard had been joined by another close by, bringing the area of vines to nearly 5 hectares.

Castell Coch wines were much liked and even proved to be a good investment, substantially increasing in value in buyers’ cellars. They were also made available far beyond Wales. In 1897 Lord Bute appointed as his agent London wine merchants Hatch Mansfield, releasing through them eight wines priced from 36 shillings to 48 shillings (£1.80 to £2.40) a dozen bottles. They were described thus on the merchants’ list: ‘Generally speaking they are soft, sweet, full-bodied, and of a luscious character, very suitable for dessert purposes.’

These Welsh wines, ‘a novelty’, had no expense spared in their production, the list continued, and, while they did not yet quite match the finest foreign wines in aroma and flavour, ‘they are eminently honest and wholesome’. Their sweetness was due to the addition of sugar before fermentation, a practice essential to achieve wines of decent alcohol level from places where it is difficult to ripen grapes fully; in the case of Castell Coch, a very large quantity of sugar was used.

Hatch Mansfield has continued to flourish since that time, although with a portfolio of non-UK wines. That is now changing, as in 2015 the company joined with Champagne Taittinger to create Domaine Evremond in Kent, the first confirmed purchase of vineyard land in England by a champagne house. Vine planting began in 2017, and hopefully this will prove a more respected and longer-lasting business initiative than the Welsh wines, which were described as ‘not exactly a success’.

Three men who launched the boat

This is the right moment to move into almost modern times, skipping over the beginning of the twentieth century. Little more of note happened before the outbreak of the First World War, and from then onwards, until the 1950s, commercial-scale English wine saw its biggest decline since its Roman beginnings. All credit then to the three people who did most to rekindle the flame of interest: horticulturist and pest control expert George Ordish, who had planted a vineyard at Yalding inKent in 1939; and writer and broadcaster Edward Hyams, in Kent, and research chemist turned enthusiastic gardener Raymond Barrington Brock, in Surrey, with their immediately post-war projects.

Ordish may not have been the most important of the three in terms of his viticultural work, but the reason he became involved is particularly appropriate today. Early in his career he had worked in Champagne, and noticed just how similar the region’s climate was to that of his home county. Why were there no vineyards in Kent, he wondered, so he set about creating his own, on a very small scale. Unlike today’s successful growers, he didn’t choose champagne grape varieties. Instead, he planted a mix of hybrids and crosses, then considered the best for outdoor growing in England but much less favoured now. The wine he made was reasonable, and the knowledge he gained prompted him to write two books on vine-growing in England, plus another on that curse of late nineteenth-century continental winemakers, phylloxera.

Edward Hyams grew grapes for both wine and table, as part of a self-sufficiency project. He and his wife had a large vegetable and fruit garden, even including a plot for tobacco, at their home not far from Ordish’s. Their wine needs, noted Hyams, were ‘a litre per head per day’! He planted a host of different imported grape varieties, and sought out established old varieties in Kent and further afield.

Much more important than his vine-growing was Hyams’ role in spreading the word that good wine could be made in England. Books, articles and broadcasts prompted a great deal of interest in a product that very few people knew about or were able to access. His message reached a huge audience. ‘Perhaps ten years hence,’ he wrote in the Daily Mirror in 1950, ‘you’ll be raising a glass of sparkling Canterbury in honour of the men who made an English wine industry possible.’ Could he have realized how truly prophetic, if a little premature, those words were?

One twenty-first century example of vine planting in Kent, at Simpsons Wine Estate. SIMPSONS WINE ESTATE

The major grape researcher of this influential trio was Raymond Barrington Brock, whose enthusiasm for gardening moved from the outdoor growing of peaches to table and wine grapes and a project to identify which varieties would flourish outdoors in England’s capricious climate. From 1945, on land around his home high on the North Downs close to Oxted, he attacked his goal with the precision of a dedicated scientist. In one experiment, he planted the same variety of vine against seven different wall surfaces, in order to assess individual performance. His vineyard areas were carefully divided into trial plots, laid out in precise, very closely planted rows and bordered by low-growing fruit trees.

Sparkling Canterbury? SIMPSONS WINE ESTATE

Zealously looking for varieties to plant, Brock appealed first for cuttings from vines already growing in England, then contacted vine research bodies throughout Europe and beyond to grow – literally – his database. The cuttings arrived, directly or indirectly, from likely or unlikely places, among them France, Switzerland, Belgium, Scandinavia, Russia and various parts of the United States. In return, as his own work began to show results, Brock sent back information and cuttings to his worldwide friends, helping to expand understanding of cool-climate vine-growing on a far wider scale. Among his correspondents was Pierre Galet, then considered the world’s greatest expert on vine identification and classification. Galet offered his support for personal as well as professional reasons: he was, he said, English from his mother’s family. There were examples of non-plant exchanges, as well – Brock sent pencils and secateurs to ill-equipped Russian researchers in return for wine from two rare Caucasian varieties.

From the first plantings of a dozen varieties in 1946, the scale of work at Brock’s Oxted Viticultural Research Station grew and grew. In 1947 twenty-nine varieties were represented in the 1,400 vines; by 1950 those figures had grown respectively to sixty and 7,000-plus. In all, Brock trialled some 600 different grape varieties over 25 years. Among them were the grapes that were soon to become crucial players in the English wine revival – müller-thurgau and seyval blanc. Many others were far less successful, with Brock sometimes despairing of time spent on fruitless work. One batch of recommended French hybrids, he complained, ‘all proved hopeless after five years of testing’, and some American hybrid cuttings sent to him from New Zealand appear to have ended up in the compost heap without a mention of their quality.

Müller-thurgau vines growing at Denbies Wine Estate – Ray Barrington Brock introduced the variety to England. AUTHOR

Brock also turned his hand to making wine from his myriad choice of grapes. Initially, things didn’t go well, a large part of his first vintage being consigned to a trial in vinegar making and some subsequent efforts ruined by oxidation or mould. But his skills had improved sufficiently by 1960 to encourage him to host a tasting of still and sparkling wines for respected trade guests, many of whom were entitled to put the prized letters of the wine profession’s top qualification, Master of Wine, after their names. Reactions were mixed, but Brock didn’t seem to mind, arguing that, alongside finding good varieties, he needed to eliminate unsatisfactory ones. He also encouraged visitors to his experimental vineyard, holding open days for the public as well as for wine trade professionals.

Brock subsidized the research station from his own income – he was managing director of a scientific instrument company until 1960 and continued working afterwards – and employed a full-time assistant. He developed his own improvements to the standard treatment for the powdery mildew that attacked his vines, wrote and lectured extensively and even had time for his hobbies of motor racing and car design. A remarkable man indeed, who, before his death in 1999 at the age of ninety-one, witnessed the resurgence of English wine to which he had contributed so much.

The value of the work of these three men is perfectly summed up by the words of Stephen Skelton, in The Wines of Britain and Ireland (2001):

Between them, Ray Brock, Edward Hyams and George Ordish had questioned why it was that outdoor viticulture in the British Isles had all but died out and had, to a certain extent, shown how it might be revived. Although they had not discovered all the answers, they had, through a combination of practical demonstration, scientific research and publicity, generated sufficient enthusiasm for those with the inclination to start planting vineyards.

The book is now out of print but it was key in telling the story of wine in the UK. Skelton is the heir of those three pioneers in so many ways: establishing successful commercial vineyards in England, selecting grape varieties that do well in them, providing technical advice to those who want to make their own mark in their country’s viticulture, and telling wine lovers why they should drink wines from UK vineyards and where they can go to see the revolution in action.