Hoar frost on a vine tendril. VIV BLAKEY/RATHFINNY WINE ESTATE

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

THE LAST WEEK OF APRIL 2017 WAS A TIME OF lows and highs for English wine. In the early hours of Wednesday the first of a succession of ‘worst in a generation’ frosts struck vineyards in Hampshire. It was particularly unwelcome as the vine buds had burst open a fortnight ahead of their normal time and the young leaves were unusually well developed. At affected vineyards the year’s potential crop was halved. In the middle of the same day, a viticulturist in Sussex was asked what future precautions he would take against frost affecting the 38,000 vines he was currently planting. ‘None should be necessary,’ came the emphatic reply.

Of course there are differences between the Hampshire sites worst hit that day, such as the comparatively exposed Leckford Estate vineyard close to Stockbridge, and the new Mannings Heath vineyard on the outskirts of Horsham in Sussex, with its ring of protective woodland. But those two experiences can serve as a valuable example of both the predicaments and the optimism within a still-new industry. What will the future hold? Will the UK’s erratic climate continue to set so many traps that wine grape-growing will never be much more than a marginal occupation? Or will the increasing knowledge and skill of viticulturists and winemakers, aided by a warmer growing season, build on the progress of the last few decades so that producing wine becomes a reliable, mainstream business?

Hoar frost on a vine tendril. VIV BLAKEY/RATHFINNY WINE ESTATE

Later that April Wednesday, Becky Hull, the buyer responsible for the largest selection of English wine stocked by any supermarket, confirmed to me that one of the biggest challenges she and others selling in quantity faced was the unreliability of supply, vintage on vintage. Ominously, a hailstorm was pounding the Waitrose head office on a Berkshire industrial estate, hardly wine land itself but with vineyards not far away. I’d just driven the 30 kilometres from the replanted historic vineyard at Painshill Park in Surrey, where the well-opened vine buds had been basking in warm sunshine, with no hint of frost damage. Those contrasts were further reminders of risk and hope.

To return to the matter of making available to mainstream drinkers the wine produced in the UK, and specifically how Waitrose, as a major supermarket, handles that. At the time we talked, Becky Hull had built the company list to around one hundred choices: some on the shelves in a broad raft of stores, more sold only in branches close to the individual vineyards, but all available online. That impressive expression of support began soon after the earliest ‘better-than-champagne’ acclaim and, over Christmas 2016, had reached a level at which one bottle of English sparkling wine was bought by Waitrose customers alongside every ten bottles of champagne they selected.

That might not sound a lot, until you read another statistic: in that year, the home-grown product comprised less than 1 per cent of all wine sold in England. So, nearly 10 per cent of sales at the prestige end of the fizz market is important. Hull revealed further significant information on customers’ buying habits, relating to product loyalty and what they choose as alternatives: when they have bought a particular bottle of English sparkling wine, they might not always go for the same one again, but they will buy another English fizz.

This shows the affection – of Waitrose customers at least – for the home product, especially when it has bubbles, and the overall rise in sales confirms that wine-knowledgeable customers who are prepared to try English wine enjoy it and keep on buying it. But there could be much more opportunity to grow the market if a bigger base of English still wine was available. ‘People buy into a country,’ Hull explained, ‘then on special occasions they will buy a bottle of fizz from that country. We don’t have that base with English wine, so it’s holding back sparkling wine.’ Much as Hull would like to broaden the Waitrose choice of English still wines, there is a way to go before they consistently match the quality of the fizz, she believes. In her view, it would help both consumers and retailers if there were a new standard to distinguish those of a higher level. More retailers taking English still wine seriously would be another step forward, as would a higher available volume, which could bring production costs down and perhaps be reflected in prices – persuading consumers to try English wine when Chilean or South African or Spanish is half the price is an uphill struggle.

In an expression of growing confidence in consumer interest, in autumn 2017 highly regarded direct seller The Wine Society put its own label on an English still wine for the first time (its Exhibition English sparkling wine, made by Ridgeview, had by then been on sale for more than three years). The still white choice was a blend from Three Choirs Vineyards in Gloucestershire, whose wines The Society had already offered for several years. The sub-£10 price was unusual for an English wine – a price, buyer Freddy Bulmer told me, largely due to the fact that Three Choirs is a long-established and commercially oriented operation, where many of the initial costs have been absorbed.

It is difficult, he believes, for UK wine producers to sell at low prices. For most there aren’t the economies of scale seen in many other wine countries. Initial expenses in particular are high and need to be recouped, there is much costly attention to detail in vineyard and winery, and of course yields are low. And then there is the further hurdle of introducing drinkers to grape varieties they have never heard of before. Convincing consumers that the wines are value for money can be hard work, but Bulmer is certain that knowledge and understanding will grow. ‘It’s fascinating to be here, in an industry in relative infancy. Watching it grow is exciting.’

Vines at Three Choirs’ Gloucestershire vineyard, source of supply to The Wine Society. THREE CHOIRS VINEYARDS

Back on the high street, Marks & Spencer has been significantly increasing its range of both still and sparkling English wine, and early in 2017 reported ‘phenomenal growth’, though within a very small overall base. It too has taken a supportive role, sponsoring a final-year student at Plumpton College, who makes a wine for the company – student number four’s wine, vintage 2016, was a still white from the three champagne varieties. The first M&S scholarship student, Collette O’Leary, who moved on to become wine development manager at Bluebell Vineyard Estates, was responsible, with another Plumpton alumnus, for a single-vineyard bacchus that joined the supermarket’s regional range in 2017.

M&S English wine buyer Elizabeth Kelly has been happy with the increasing quality and range of wines available, but less content that ‘there aren’t enough grapes to go round’, putting pressure on prices. But for whites and rosés, particularly pinot noir rosés, she believes many buyers – especially in London and similarly wine-savvy locations – are prepared to pay a premium. Better consumer understanding of English wine is crucial, and ‘the message seems to be getting out there’. She has contributed on a personal scale: ‘I’ve converted most of my friends now!’ Such individual effort should not to be underestimated, for word of mouth is a powerful promotion tool.

Buyers of English wine fall into a ‘very specific demographic’, says organic grower Kristin Syltevik, whose previous expertise before she founded Oxney Estate was in public relations. They are young professionals who are yet to start a family and well-off older people, groups ready to experiment and with the disposable income to accept that home-produced wine will never be at bargain-basement prices.

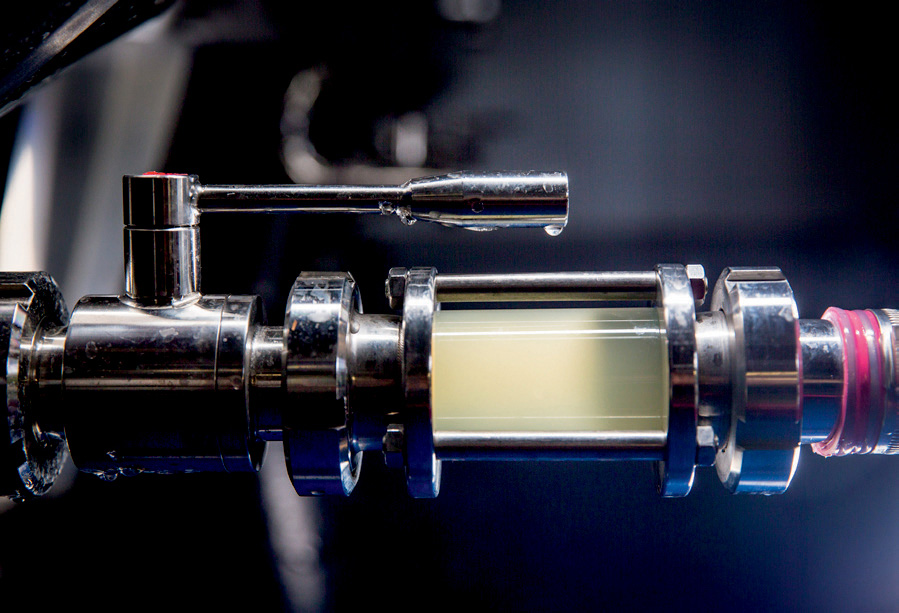

Juice from the 2016 harvest at Simpsons estate on the way to becoming sparkling wine. SIMPSONS WINE ESTATE

How can that demographic be broadened? ‘Try’ is a crucial word: too few wine drinkers are familiar with English wine. Albury Vineyard’s Nick Wenman, who has worked effectively with local Surrey publicans to bring his organic wines to broader notice, calls on more sommeliers to include English wine on their lists. More than that, they need to offer English sparkling wine by the glass. ‘At £6.95 a glass rather than £40 a bottle it’s much easier for people to take the plunge,’ he argues.

Keen supporters of English wine already include leading restaurateurs: Raymond Blanc, Tom Kerridge and Angela Harkness are among the top chefs who want their diners to be able to drink wine as well as eat food whose origins lie as close as possible to their kitchens. And initiatives such as the many events during English Wine Week do a great deal to bring in new consumers.

Further down the sparkling wine production line: bottling at Gusbourne. GUSBOURNE

But will there be a big enough market in the UK and further afield to absorb all the extra wine that is coming on stream, the sparkling particularly? Some in the industry are entirely optimistic, believing that, increasingly, English sparkling wine will be poured instead of champagne and other fizz. After all, the homegrown share of the booming sparkling market in the UK is still tiny. Support for homegrown products and opposition to transporting food and drink over huge distances has already massively helped the UK wine industry and should continue to do so. There will never be the sort of wine glut that some other countries suffer, but there are concerns that big increases in grape production could put pressure on prices, leading to viability problems within the industry, or open the door to bulk buyers turning out lower-grade wine. That, says Julia Trustram Eve, marketing director of WineGB, is one reason why it is crucial that there should be a strong trade organization for English and Welsh wine.

In May 2016, Ridgeview chief operating officer Robin Langton was asked by trade magazine The Drinks Business how he thought sparkling wine sales would evolve in the next five to ten years. ‘Honestly, it’s crystal ball territory,’ he replied. ‘However, I hope that in ten years some of the thousands of Prosecco aficionados will finally be getting bored of this generic ambrosia and will be falling in love with ESW! At the premium end of the market, English sparkling wine will be the automatic choice of discerning consumers, quality grocers and the favourite at your special restaurant.’

That ‘decade-ahead’ moment has already arrived for some. ‘At the moment I cannot make enough wine,’ Chapel Down head winemaker Josh Donaghay-Spire told me a year after Langton‘s prediction was published. ‘We are in a position where the sales team are not selling, they are managing demand.’

Tasting bar at The Wine Sanctuary, Chapel Down, opened in 2017. CHAPEL DOWN

Mardi Roberts: ‘Together we are stronger.’ AUTHOR

In early 2017, Plumpton College’s Chris Foss reckoned the growth could last perhaps a further five years. Looking beyond that, however, he was less sanguine. ‘I think there will almost certainly be problems in ten years.’ Others have suggested the home market’s capacity may be reached even sooner. So export is crucial. The aim is to move from the 2015 base of 250,000 bottles to 2.5 million by 2020 – a quarter of likely total production.

Many of the bigger producers have progressed steadily towards achieving that. Ridgeview, for example, signed up a US-wide distributor in late 2016, when already a fifth of its production was leaving UK shores for more than a dozen different countries. Increasing both the number of bottles exported and the destinations to which they go is essential for the future of the business, says sales and marketing manager Mardi Roberts. For English drinkers, the local product is pricey and to rely on them alone would be risky. ‘We won’t be able to do price wars, we can’t put all our eggs in one basket.’ She argues for a combined effort by producers to promote exports. ‘Together we are stronger, proving English sparkling wine is not a joke. There is room in the world market.’

Chardonnay: for sparkling wine and, in good years, still. GUSBOURNE

Coates & Seely is another estate seeing, and seizing, that opportunity. In 2017 some 25 per cent of its 65,000-bottle annual production was sold to sixteen countries overseas – even reaching the legendary George V hotel in Paris. Chapel Down also counts France among its export destinations, an achievement in which head winemaker Josh Donaghay-Spire takes ‘disproportionate pleasure’. Exton Park announced in May 2017 that its foreign markets had expanded to include Italy, itself a major bubbly producer. A month earlier, Waitrose headed a broad initiative to export English sparkling wines to China, selling bottles from four estates, including its own Leckford vineyard, through an e-commerce retailer similar to Amazon.

Export is the principal focus of a rather different player from the conventional grower-producers, Digby Fine English, whose wines are made from grapes sourced from contracted vineyards. ‘The next twenty years will be the hard time,’ co-founder Trevor Clough predicted when questioned in 2017. ‘There is a lot of work to do to evangelize, to spread the word.’ But export, he says, is where money is to be made.

For all in the industry the USA is a prime market, and in summer 2016 the first-ever full container load of English fizz to be exported – 5,000-plus bottles, from several producers – crossed the Atlantic. Other destinations for English wine include Canada, South Africa, Australia, Hong Kong and the UAE: in 2016 bottles were shipped to twenty-seven countries. But whether at home or abroad there is confidence that English sparkling wine will find ready sales if it remains a premium product, worthy of its price.

What of still wine? Will the improving trend continue? General feeling is that it will, with some predictions that the still/sparkling split may eventually even out. Nyetimber owner Eric Heerema doesn’t agree. ‘There’s local demand, people are proud of serving local wines, but it will never become big,’ he said in a Wine Searcher interview in February 2016. ‘Remember also that there’s an ocean of still wines in the world, and in England the yields are lower and the costs higher.’ For English still wine really to take off, says Chris Foss, there would need to be the same breakthrough as sparkling has seen: international prizes, a substantial rise in production.

Stephen Skelton suggests something else could be more important: the cash reward for those who produce the wines. ‘Sparkling has got a massive lead and still wine will be in a minority for years to come,’ he told me. ‘Having said that, if the climate continues to improve and people can sell good still wines at £15–£20, then this is so much more attractive than selling sparkling at £25–£30 that some of the production will switch.’

As for the grape varieties from which those still wines might be made, Skelton believes that climate will be the crucial factor. ‘If 2016 is a marker, then chardonnay and pinot noir, plus pinot blanc and gris, become a reality. They are good because in the less ripe years they can go into sparkling and still be called “pinot”. I don’t see sauvignon blanc becoming mainstream, and I don’t see riesling getting anywhere. Bacchus is here to stay and has enough critical mass to get known by the wine-buying public. Of course, as vineyards in the south appear to grow and prosper then people in the less favourable areas of the UK will be encouraged to try growing grapes. They will have to be growing varieties like reichensteiner, seyval, solaris, etc, because they won’t get decent crops with chardonnay and pinot noir.’

Foss agrees on the potential for bacchus, pinot blanc and pinot gris. But wait a few more years, and sauvignon blanc and riesling could be joining, even overtaking, them. ‘In twenty years it will be like the Loire Valley, in another twenty, like Bordeaux,’ he suggested to me, speaking of grape varieties as much as of climate. And the simple message of Greyfriars owner Mike Wagstaff to growers with non-sparkling ambitions is that they should produce wines from grape varieties that are familiar to wine drinkers.

Flourishing vines at Biddenden: if the cost of English wine production is properly explained, consumers are more inclined to accept its price, says marketing manager Victoria Rose. BIDDENDEN VINEYARDS

Which points, again, to spreading the word. There is still too little knowledge about the wine made in the UK, even on home ground and especially away from London and the south. Biddenden marketing manager Victoria Rose, who hails from a long way north of Watford, admits to being one of the ignorant herself only a very short while ago. ‘Before I moved to Kent four years ago,’ she told me early in 2017, ‘I didn’t know English wine existed.’ But she isn’t alone in being a quick learner. ‘It’s incredible how far knowledge has come recently. Now it’s getting to that point in Kent where not only will every restaurant and pub have it but everybody knows about it. But there is a north-south divide.’

Even for cellar door sales, Rose adds, price remains a hurdle. ‘Everything comes down to the story and the time you have to explain things to people.’ Low yields, climate volatility, contributing to the local economy by providing jobs for local people, the cost of planting vineyards and equipping wineries are all factors – these and more mean that UK-produced wine will never be a cheap product. But wine tourists accept that, she says, once they understand the reasons why.

Cherie Spriggs recalls that when she was appointed head winemaker at Nyetimber in 2007 she was ‘shocked how few people knew about wine being made in England’. A decade later, things had changed: ‘Now thankfully there is much better recognition here that we make English sparkling wine of quality that is as good as, if not sometimes better than, champagne. But we’re not there yet.’ Specifically, she said, more work had to be done beyond UK shores. ‘Other countries still have a very poor understanding of English sparkling wine.’

Who, though, will be making those predicted millions of bottles as production continues to expand? Quite possibly not as many individually owned vineyards as exist now. Many in the UK wine industry expect some consolidation, and that has started to happen. One example was the purchase in March 2017 of Henners Vineyard in East Sussex by 44-million-bottles-a-year wine distributor Boutinot. It was the development of an existing relationship, for Boutinot had been agent for Henners since the release of its first wine in 2012, and owning an English sparkling wine company fits well in the distributor’s business plan. A significant proportion of Boutinot’s portfolio of wines is made in vineyards it owns round the world, in locations including France, Italy and South Africa.

Nyetimber owner Eric Heerema isn’t surprised at such developments. In the 2016 Wine Searcher question-and-answer session he summed up his prediction for English wine thus: ‘I think there will be more professional enterprises, both start-ups and also from producers consolidating with the aim of becoming more viable and sustainable. So there will be fewer and stronger producers. The biggest difference will be international awareness.’

Perish the thought that the UK might turn into solely a big-brand wine producer. But it won’t, if the sensible people now making good wine continue to do the right thing. If you’re a small grower and want to survive independently, ‘you have to have your niche’, says Albury’s Nick Wenman. If you want to be successful, whatever your size, it’s all about location, location, location, insists Charles Simpson: ‘I cannot emphasize that enough. Site selection is the single most important success criterium.’ Camel Valley’s Bob Lindo believes anyone producing English wine needs to be enthusiastic about the product itself, not just its money-making potential, or they will be deterred by the lack of consistent vintages.

There are certainly ways of establishing a viable business that do not rely on coming in with a big and possibly expendable fortune. Producers such as Simpsons, Hambledon and Chapel Down have shown that successful use of crowd-funding, for example, can bring in word-spreading supporters as well as necessary cash.

One characteristic of the fledgling UK wine industry is that there has been little blatant rivalry among those working in it – other, perhaps, than at the ‘one-day Olympics’ held between Hampshire and Sussex vineyards. Many of the growers I spoke to went out of their way to emphasize how they worked together, organizing joint promotional initiatives, sharing information and ideas, lending equipment if a neighbour suffered a breakdown. The message to get over, they insisted, was about the quality and variety of English wine, not pushing individual producers’ names. That united, friendly approach may disappear as the fastest-growing sector in UK agriculture becomes bigger and bigger, but I hope not. The all-for-one-end ethos should be cherished. As the late Mike Roberts, founder of Ridgeview, so aptly said: ‘Everybody has contributed. It’s what we do together that makes it work.’

The final words on the future of wine production in the UK should surely go to two people who have played a particularly important role in its present success. The first is Stephen Skelton, whose CV is impressive indeed. Skelton planted his own vineyard at Tenterden in Kent in 1977 and made wine there for twenty-two consecutive vintages. He has advised scores of would-be followers through a comprehensive consultancy service, lecturing and his books – essential reading for anyone who wants to grow wine vines successfully and profitably in the UK and other cool-climate locations. He sources and supplies vines. He gained his Master of Wine qualification with a dissertation on yeast, a fundamental element in winemaking. He has held leading positions in UK growers’ organizations. He is a chairman of judges at major international wine competitions, including heading the English regional panel in the Decanter World Wine Awards.

Vines at Exton Park, one of the group of Hampshire vineyards that work together to promote their wines. EXTON PARK VINEYARD

I asked him whether, if he were to start his career in wine now, he would follow a different path. ‘Not a lot different,’ he replied. ‘I would have made sure that I fully appreciated how much capital I needed to get established and made sure I had investors on board able to see things out for the first ten years. I would have got into direct wine sales sooner, and concentrated on tourism and visitors earlier. That way I could have sold all my wine direct. Selling wine via wholesalers and retailers hammers the margins. I would of course have started out making both still and sparkling, and started out bigger.’

And his view on the future of wine in the UK? For Skelton, the ‘elephant in the room is yield and, with it, profitability’. There is a major issue, too, with continuing poor site selection among some entrants in the industry. Overall, however, his optimism far outweighs his concern. ‘I wish I was 26 again and just starting out. The industry will only get bigger and bigger and with the wave of sparkling wine yet to come on to the market the public will be even more exposed to English wines and the demand will follow.’

Stephen Skelton (at the Domaine Evremond planting): ‘The industry will only get bigger and bigger.’ THOMAS ALEXANDER PHOTOGRAPHY/DOMAINE EVREMOND

The second essential figure in the success story is Julia Trustram Eve, for whom the turn of the calendar to 2018 marked twenty-five years of a leading role in promoting the wines of England and Wales. That all began when, moving out of London after marriage, she retained the wine-trade links of her earlier career by working for an English vineyard. It was a time when enthusiasm was growing among vineyard owners to co-operate to bring their wine to wider notice, and Trustram Eve was instrumental with them in establishing English Wine Producers. She became the group’s marketing director – a role she retained as WineGB was established – and has prompted much of the increasing acceptance that English wine is a serious item on the world list.

Julia Trustram Eve (at the Mannings Heath planting, with viticulturist Duncan McNeil): ‘We are only at the very, very beginning of what are extremely exciting prospects.’ AUTHOR

She has seen and celebrated the changes over that time, and is full of optimism for what is to come. ‘We have yet to see most of what is going to happen from the vines that have been planted over the last ten years,’ she told me immediately after the announcement of the EWP/UKVA merger agreement in 2017. Sparkling wines will remain the main focus, with even brighter prospects as increased quantities of reserve wines become available to increase future potential. Still wines, she added, ‘can only get stronger and stronger’ as growers identify the best grape varieties, with ‘a tremendous future’ for bacchus as England’s signature variety. She welcomes the prospect of more white wines from pinots blanc and gris, and reds from pinot noir, and hopes perhaps that gamay might one day join the list of English classics.

The future is bright, believes Trustram Eve: ‘There are huge opportunities. We know we are producing a world-class style, and I have no doubt about the vision and focus of the sparkling wine producers. We are only at the very, very beginning of what are extremely exciting prospects.’

CHAPEL DOWN

So there is every likelihood, not very far ahead, that the south-facing slopes of the Sussex Downs that I see from my living room window will be covered in tidy rows of vines, never a sheep in sight. I’ll raise a glass of English sparkling wine to that.

TOM GOLD PHOTOGRAPHY/WINEGB