April—a young student shoots dead Minister of Interior. July—a worker shoots governor of Kharkov. Waves of peasant riots in the countryside; some ninety estates plundered, with the help of Socialist Revolutionary “expropriators”.

June—Tolstoys leave the Crimea. Tolstoy works on two plays, The Light Shines Even in Darkness and The Living Corpse, a few short stories, an essay on Shakespeare and a popular anthology, Thoughts of the Wise Men for Every Day. Sofia works on the eleventh edition of his Complete Works.

1st January. We had a quiet family New Year party yesterday. (Lev Nikolaevich had to go to bed early, as he felt ill after his bath.) Klassen came this morning with some lovely violets.

I am copying Lev Nikolaevich’s article ‘On Religion’ a little at a time, but it lacks something—it needs more passion, more conviction.

I took a walk to the Yusupovs’ Park and the coast, with Olga and Tanya. It was a warm, summery day, and by the sea we met Gorky and his wife. Then Altschuler called. Our servants all came in dressed as mummers and stamped and danced about; it was terribly tedious—I am much too old for that sort of thing.

I wrote five letters, finished knitting a scarf and gave presents to Ilya Vasilevich and the cook. I received charming letters from my daughters-in-law Sonya and Lina, and felt so pleased that at least two of my children, Ilya and Misha, are happily married. What will this new infant Vanechka Tolstoy be like?

4th January. For the past three nights I have been sleeping on the leather sofa in the drawing room, or rather not sleeping but listening out all night for Lev Nikolaevich next door. His heart has been very irregular. Yesterday and today he came down to dinner, but grew dreadfully weak afterwards, and today we summoned Tikhonov, the Grand Duke’s doctor, from Dülber. He warned of dire consequences if Lev Nikolaevich continued to lead this reckless life, overtiring himself and overeating.

Seven inches of snow fell in the night, and it is still on the ground. Yesterday there was a north wind and 3 degrees of frost; today it is half a degree above freezing, with no wind. I knew this weather would have a bad effect on him. It always does.

I am looking after him on my own, but his obstinacy, his tyrannical behaviour and his complete ignorance of hygiene and medical matters makes it terribly hard, even unbearable at times. For instance, the doctors order him to eat caviar, fish and bouillon, but he refuses because he is a vegetarian—it will be the ruin of him.

I have been reading an extraordinary little book, a translation of Giuseppe Mazzini’s On Human Duty.*

5th January. Palpitations, difficulty in breathing, insomnia, general misery. Several times during the night I got up and went to him. He drank some milk with a spoonful of cognac, took some strophanthus, which he asked for himself, and managed towards morning to get a little sleep. Doctor Tikhonov called yesterday evening, and again today, and said there was an infiltration of the liver, a weakness of the heart and a disorder of the intestines. These complaints appeared long ago, but are now following their course in a more pronounced and malignant fashion, and manifest their ominous symptoms yet more frequently and painfully.

L.N. is very dejected, and keeps us all at a distance, calling us only if he needs something. He sits in a chair, reads or goes to bed. He slept very little again today.

There is snow on the ground and the temperature is at freezing point. A terrible wind has been howling all day. The whole place is cheerless and desolate. I have put all thoughts of Moscow out of my mind for now—although it’s essential that I go!

I sit at home all day sewing and ruining my eyes; I am sunk in torpor, as I used to be in my youth at Yasnaya Polyana. But then I had children!…

8th January. Doctor Altschuler and Doctor Tikhonov came yesterday and prescribed a twice-weekly dose of extract of buckthorn, in tablet form, and five drops of strophanthus three times a day for six days. But he refuses to take anything. I am tired of this forty-year struggle, I am tired of having to employ tricks and stratagems to make him take this or that medicine and help him get better. I no longer have the strength to struggle. There are times when I long to get away from everyone and withdraw into myself, if only briefly.

All this morning I was copying out his ‘On Religion’. This is more of a socialist work than a religious one.

I told him this yesterday. A religious work should be poetic and exalted, I said; his ‘On Religion’ was very logical but didn’t capture the imagination or elevate the soul. He replied that it needed only to be logical, a lot of poetry and lofty obscurity would only confuse the issue.

I was thinking about my trip to Moscow again.

10th January. The atmosphere here is so gloomy at times. I am sitting alone after dinner sewing in the dark drawing room. Lev Nikolaevich is next door in his room. Tanya is tapping away on the Remington on the other side, Seryozha is silently reading the newspapers in the dining room, and Olga is upstairs with Sonyusha. There is silence in the house, broken at times by terrible gusts of wind, which howls and groans and stalks the rooms, filling them with cold.

He is so weak at present, he often calls me simply to cover him with a rug or adjust his blanket. I have to make sure he doesn’t overeat, that people don’t make a noise when he is trying to sleep and that there are no draughts. I have just put a compress on his stomach. He drinks Ems water twice a day.

11th January. I went to Yalta with Tanya to do some business and shopping, and brought her a hat for her name day. Masha was looking very thin and wretched.

Poor Olga’s baby has stopped moving inside her in her sixth month. I feel so sorry for her. I brought Sasha home. Yesterday she rode her horse over to Gurzuf, and today she attended a rehearsal of It’s Not All Cream for the Cat, in which she plays Fiona. I have now finished copying ‘On Religion’, which I began to like better towards the end. I like what he writes about the freedom of a man’s soul illuminated by religious feeling.

12th January. The whole day was absorbed by worries. First I played with my granddaughter, then comforted poor Olga who was weeping for her baby; then I washed and mended Seryozha’s cap; then I gave Sasha some advice about her theatrical costume; then the doctor came to see Olga; then this evening I prepared an enema for Lev Nikolaevich; then I put a compress on his stomach and brought him some wine, and he drank some coffee that had been heated up for him.

Tanya’s name day. She has arrived from Yalta and is in a melancholy mood. Andryusha too is sad and quiet: his marriage is in difficulties and I feel very sorry for him. Seryozha has just left for Yalta, intending to celebrate the first day of the Moscow University year. He has spent the last few days playing the piano on his own in the side wing. I have been deprived of even that pleasure now! I cannot leave the house, I cannot leave Lev Nikolaevich or Olga with anyone. My old age is turning into a sad time. Yet that storm of desires and aspirations for a more spiritual, more significant life has not been extinguished in my soul.

14th January. How time flies…There is no winter here and no certainty. There is nothing to rejoice about either. Lev Nikolaevich’s health isn’t improving. This great man has a dreadfully obstinate nature. He refuses the diet of fish and chicken that has been recommended, and insists on eating carrots and red cabbage as he did today, then suffering for it.

I sat by his room until half-past three in the morning yesterday, waiting for Andryusha and Seryozha to return from an evening of cards. He slept well. At the moment I am copying out his letter to the Tsar.

16th January. A terrible night. L.N.’s temperature went up to 38. I spent the night in the drawing room next to his bedroom and had no sleep at all. Yesterday and today we rubbed him with iodine and applied a compress. He had five grains of quinine at 2 in the afternoon, and has been taking 5 drops of strophanthus twice a day. Despite all this he got up, did some writing and played vint with Klassen, Kolya Obolensky and his sons.

17th January. The same medicine, the same pain in his side, although he is a little more cheerful. Chekhov called,* and Altschuler. The weather is warm and fine. Tanya has left to see her husband in the country. I have just copied out L.N.’s letter to the Tsar—an angry insulting letter, abusing everything on earth and giving him the most absurd advice on how to run the country. I do hope Grand Duke Mikhailovich understands it is the product of a sick liver and stomach and doesn’t give it to the Tsar; if he does, it will infuriate him and he may take action against us.

18th January. I put my husband to bed every evening like a child. I bind his stomach with a compress of spirit and camphor mixed with water, I put out a glass of milk, a clock and a little bell, I undress him and tuck him up; then I sit next door in the drawing room reading the newspapers until he goes to sleep. I have summoned up all my patience and am doing my utmost to help him endure his illness.

20th January. I went to see Sasha in the role of Fiona the old housekeeper in It’s Not All Cream for the Cat, which is being performed in the local library. It was Sasha’s first acting attempt, and she wasn’t at all bad. The cast was a strange mixture of people—a doctor’s wife, a blacksmith, a nurse, a stonemason and a countess. This is all good.

Lev Nikolaevich is better, his stomach isn’t hurting and his temperature was 36.9 this evening, as it was yesterday. He took some strophanthus, but refused to take quinine. We didn’t apply a compress today.

There has been a thick fall of wet snow.

23rd January. Doctor Bertenson (a distinguished physician-in-ordinary) arrived from St Petersburg yesterday evening. Today clever Doctor Shchurovsky came from Moscow, and the two of them had a serious consultation with Altschuler. I shall note down their recommendations for Lev Nikolaevich:

Regime:

- 1. Avoid all exertion, physical and emotional.

- 2. Not to go for long walks. Horse-riding and climbing strictly forbidden.

- 3. To rest for 1 to 1½ hours every day, taking his clothes off and going to bed.

- 4. To have three meals a day and eat no peas, lentils or red cabbage. To drink no less than four glasses of coffee with milk every day (¼ coffee to ¾ milk). If milk is drunk on its own, it must be taken with salt (¼ teaspoonful per glass).

Wine may sometimes be replaced by porter (no more than two Madeira glassfuls per day).

- 5. To take a bath every two weeks. The water to be 28 degrees and the soap (half a pound) to be dissolved into it. To sit in the bath for five minutes and sponge himself with clean water of the same temperature.

In the interval between baths to rub the body with a solution of soap spirit and eau de Cologne.

Treatment:

- 1. A twice-weekly enema made from 1 pound of oil slightly warmed, to be administered at night.

For the other days, 1–5 pills to be taken at night. If the pills prove ineffective, to administer a water enema in the morning.

- 2. Glass of Karlsbad Mühlbrun, slightly warmed, to be drunk three times a day for one month.

- 3. Three camomile capsules a day for three days; repeat after two days, and so on.

- 4. Should heart medication (strophanthus) be required, this must be administered by a doctor.

- 5. In the eventuality of a bad nervous illness, capsules (+ Coff) should be taken for the pain.

If the doctor considers it necessary to give quinine under the prescribed regime, this must not be obstructed.

Lev Nikolaevich’s diet must consist of: four glasses of milk and coffee a day.

Gruels: buckwheat porridge, rice, oats, semolina with milk.

Eggs: fried, whisked raw, in aspic, scrambled with asparagus.

Vegetables: carrots, turnips, celery, Brussels sprouts, baked potatoes, potato purée, pickled cabbage chopped fine (?), lettuce scalded in hot water.

Fruits: sieved baked apples, stewed fruit, raw apples chopped small; all oranges to be sucked.

All sorts of jellies and creams are good; meringues.

Written later, on the evening of the 23rd. Lev Nikolaevich had a terrifying attack of angina and his temperature went up to 39°.

24th January. The doctor listened to his heart this evening and diagnosed pleurisy in the left lung. Shchurovsky has returned and is treating him.

25th January. They have decided it is pneumonia of the left lung, which subsequently spread to the right one too. His heart has been bad all this time.

26th January. I don’t know why I am writing—this is a conversation with my soul. My Lyovochka is dying…And I know now that my life cannot go on without him. I have lived with him for forty years. For others he is a celebrity, for me he is my whole existence. We have become part of each other’s lives, and my God what a lot of guilt and remorse has accumulated over the years…But it is all over now, we won’t get it back. Help me, Lord. I have given him so much love and tenderness, yet my many weaknesses have grieved him! Forgive me Lord! I ask for neither strength from God nor consolation, I ask for faith and religion, God’s spiritual support, which has recently helped my precious husband to live.

27th January. I would like to record everything concerning my dear Lyovochka, but I cannot; I am suffocated by tears and crushed by the weight of my grief…Yesterday Shchurovsky suggested Lyovochka inhale some oxygen, and he said: “Wait a bit, first it’s camphor, then it’s oxygen, next it’ll be the coffin and the grave.”

Today I went up to him, kissed his forehead and asked him: “Is it hard for you?” And he said: “No, I feel calm.” Masha asked him: “Is it horrible, Papa?” And he replied: “Physically, yes, but emotionally I feel happy, so very happy.” This morning I was sitting beside him and he was groaning in his sleep, when he called out suddenly in a loud voice: “Sonya!” I jumped up and bent over him and he looked at me and said: “I dreamt you were in bed somewhere…” Then the dear man asked me whether I had slept and eaten…This is the first time anyone has asked about me! Oh Lord, help me not to expect anything from people, and to be grateful for everything that I may receive from them.

His pleurisy is pursuing its terrifying course, his heart is growing weaker, his pulse is quick, his breathing is short…He groans day and night. These groans carve deep scars into my heart—I shall hear them for the rest of my life. He often talks at length about what has been preoccupying him lately: his letter to the Tsar and other letters he has written.

I once heard him say: “I was wrong,” then “I didn’t understand.”

He is generous and affectionate with everyone around him, and is evidently well pleased with the treatment he is receiving. “That’s wonderful,” he keeps saying.

No, I cannot write, he is groaning downstairs. He has had several injections of camphor and morphine.

He once said in his delirium: “Sevastopol is burning.” And then he called out to me again: “Sonya what are you doing? Are you writing?”

Several times he asked: “When is Tanya coming?” and “What time is it?” He asked what the date was, and whether it was the 27th.

28th January. Tanya, the Sukhotins and Ilya have come, bringing a lot of noise and worries about food and accommodation. How frightful it all is: the painful struggle of a great soul in its passage to eternity and oneness with God, whom he has served—and all these earthly cares in the house.

It is so hard for him, the dear, wise man…Yesterday he said to Seryozha: “I thought it was easy to die, but it isn’t, it’s terribly hard.”

He has just called Tanya in to see him. He was so happy when she arrived. He was also pleased to get a telegram from Grand Duke Nikolai, saying he had personally handed his letter to the Tsar.

Doctor Volkov is on duty one night, Altschuler the next, and Elpatevsky the third; Shchurovsky is here all day.

29th January. 9 o’clock in the morning. They insisted I go upstairs and get some sleep, but having spent the past hour sobbing I now feel like writing again. My Lyovochka (although he isn’t mine now but God’s) had a terrible night. The moment he dropped off he started choking and shrieking and couldn’t sleep. First he asked Seryozha and me to sit him up in bed, then he drank some milk, followed by half a glass of champagne and some water. He never complained but he was tossing about and suffering terribly.

I have a spasm in my chest every time he groans. How can I not suffer too, when my other half is suffering?

Every loved person’s passage to eternity enlightens the soul of those who tenderly bid him farewell. Oh Lord, help my soul remain to the end of my life in this lofty enlightened state that I experience increasingly these days! He has just gone to sleep and Liza Obolenskaya and Masha have taken my place. I sat with him until 4 in the morning.

30th January. Yesterday morning he was feeling so well that shortly before 1 he sent for his daughter Masha and dictated into his notebook roughly the following words: “The wisdom of old age is like carat diamonds: the older it is the more valuable it is, and must be given away to others.” Then he asked for his article on freedom of conscience, and began to dictate various corrections to it.*

His temperature was normal all day and he was in good spirits, and we all cheered up. This evening I took up my nightly vigil by his bed; I sat with him until four in the morning, listening to his breathing, and all was well.

Lyova arrived yesterday evening. I always love to see him.

Misha too came this evening, bubbling with life as usual.

At about three he began choking and tossing, then he went to sleep.

It is now eight in the evening and he is sleeping peacefully.

He generally calls for Andryusha when it is time for him to change position, and he eats most happily from Masha’s hand. My suffering for him is involuntarily communicated to him, he often strokes my hand and tries to spare my strength, and will accept only the lightest personal attentions from me now.

31st January. He had a bad night. He tossed and gasped until 4 a.m., called twice for Seryozha and asked him to sit him up in bed.

Yesterday he said to Tanya: “What was it they said about Count Olsufiev? That he had an easy death?* Well it’s not at all easy, it’s hard, very hard, to cast off this familiar skin,” he said, pointing to his emaciated body.

He was better today and called for Dunaev and Misha; every new arrival delights him. Ilya’s wife Sonya also arrived today. It’s noisy and crowded here, but the death of my beloved husband pursues its natural course.

He has been dictating notes for his notebook again, as well as for some articles he has already started. He looks so peaceful and serious in bed. He dictated a long telegram to his brother Sergei.

1st February. He has had a terrible night. He was awake until seven in the morning, he had a stomach ache and was gasping for breath. I massaged his stomach several times, but it didn’t help. Once he fell asleep for ten minutes while I was massaging, and I stopped rubbing and froze, kneeling on the floor, with my hand on his left side. I thought he would take a nap, but he soon woke up and started groaning again. At five in the morning I went out and Liza and Seryozha took my place. At seven o’clock we woke Doctor Shchurovsky, who gave him a morphine injection. Doctor Elpatevsky also kept watch over him, but by then he was so exhausted he went to sleep. He had a fairly peaceful day, and Shchurovsky put another plaster on his left side.

He dictated some notes to Masha for his notebook.

2nd February. Ilya’s wife Sonya came yesterday evening, as well as old Uncle Kostya and Varya Nagornova. Lev Nikolaevich is delighted to have visitors.

At three in the morning he had a small morphine injection (a sixth of a grain), and ten minutes later fell asleep and slept till morning. Today for the first time his temperature was 35.9 instead of 36.9. He tucked into an egg and some tapioca with milk, and is looking forward to a meringue for dinner—the doctor has allowed this.

He dictated to Masha some corrections to his article ‘On Freedom of Conscience’.

Yesterday all the children and I had our photograph taken—in memory of a sad but important time.

3rd February. The Russian Gazette has at last published news today of Lev Nikolaevich’s illness.

Yesterday morning Lyova left for St Petersburg.

He has taken a little soup, an egg and a meringue. He asked Sonya, “Where did you bury your mother last year?” “We took her body to Paniki, at my brother’s request.” “How senseless,” he said. “What’s the point of moving a dead body?”

5th February. The situation is unchanged. A night under morphine—they gave him an injection of 1/8 of a grain. He drinks champagne and milk with Ems water, and eats puréed oat soup, eggs and gruel. We applied a compress today. I am sitting here exhausted and numb; it has all been too much for my heart, and now I have slumped, waiting.

6th February. A sleepless night, two injections of morphine, nothing helped. At 5 a.m. I went to bed exhausted. A morning of anxieties.

Elpatevsky and Altschuler came. They say this is the crisis. The pneumonia has suddenly started to clear from both lungs. But what will happen when his temperature falls? We are living in terror. “Everything is in the balance,” he said today to his niece Varenka. He is taking his own pulse and temperature, and is very frightened; we are forced to deceive him and reduce the degrees.

The cold and wind make things worse.

7th February. The situation is almost hopeless. Until 5 o’clock I was doing all I could to relieve his suffering. The only time my darling Lyovochka dropped off was when I lightly massaged his stomach and liver. He thanked me and said: “Darling, you must be exhausted.”

Olga’s pains began this morning, and at seven she gave birth to a dead baby boy.

Today Lev Nikolaevich said: “There, you’ve arranged everything perfectly, give me a camphor injection and I’ll die.”

He also said: “Don’t try to predict what will happen. I can’t foresee anything.”

He asked for the medical notes on the progression of his illness—his temperature chart, medicines, diet and so on—and read it closely. Then he asked Masha what she had felt during the crisis in her typhus attack. Poor, poor man, he so wants to go on living, yet his life is slipping away…

There is thick snow on the ground and a strong wind. Oh this hateful Crimea!

Tonight there were eight degrees of frost.

8th February. He spent a slightly more comfortable night.

He called Masha today and dictated a page of ideas to her—against war—“fratricide”, as he calls it.*

I sat with him until five in the morning; I turned him over with the help of Boulanger, changed his soaking underwear and gave him his medicine (digitalis), and some champagne and milk.

When I examine my soul I realize that my entire being aspires only to nurse this beloved man back to life. But when I’m sitting with my eyes closed, all sorts of dreams suddenly creep up on me, and plans for the most diverse, varied and improbable life…Then I come back to reality and my heart aches again for the death of this man who has become so much part of me I couldn’t imagine myself without him.

A strange double life. The cause, I tell myself, is my own indestructible health, my enormous energy, that demands an outlet and finds nourishment only in those difficult moments when it is really necessary to do something.

9th February. The other day he said: “It keeps hurting. The machine has broken down. Pull the nose and the tail gets stuck, pull the tail and the nose gets stuck.”

Yesterday was a fine day, and he was better. It is snowing again today, and it’s dark, overcast and freezing.

10th February. Another fine day—it was 3 degrees. Our dear invalid had a good night and was in less pain during the day, although he is still dreadfully weak and had a temperature of 36.3. He hasn’t said a word all day, nothing interests him, he just lies there quietly. He had three small glasses of coffee, asked for some champagne and was given two camphor injections. He is peaceful and I feel fairly calm.

12th February. He has been very weak and drowsy, and hardly speaks at all. Yesterday he asked Doctor Volkov how the common people cured old men like him—did they give them camphor injections? Who lifted them up in bed? What did they give them to eat? Volkov answered all his questions, saying they treated them just the same, and it was generally the family or the neighbours who attended to them, lifted them up and helped them.

14th February. An anxious night. It’s a long time since I felt so weak and exhausted.

I read my unfinished children’s story ‘Skeletons’* to the children, Varya Nagornova and some young ladies, and they seemed to like it.

As for Lyovochka, I simply don’t know what to think: I don’t know whether this weakness is temporary or terminal. I keep hoping, but today matters have again taken a gloomy turn.

How I should love to look after him patiently and gently to the end, and forget all the old heartaches he has caused me. But instead I cried bitterly today at the way he persistently scorns my love and concern for him. He asked for some sieved porridge, so I ran off to the kitchen and ordered it, then came back and sat beside him. He dozed off, the porridge came and when he woke I quietly put it on a plate and offered it to him. He then grew furious and said he would ask for it himself, and that throughout his illness he had always taken his food, medicines and drinks from other people, not me. (Although when someone has to lift him up, go without sleep, attend to him in the most intimate ways and apply his compresses, it is of course me whom he forces mercilessly to help him.) With the porridge, however, I decided to employ a little cunning, so I called Liza and sat down in the next room, and the moment I left he asked for the porridge, and I began weeping.

This little episode summarizes my whole difficult life with him. This difficulty consists of one long struggle with his contrary spirit. My most reasonable and gentle advice to him has always met with protest.

15th February. I received a letter from the St Petersburg Metropolitan Antony exhorting me to persuade him to return to the faith and make his peace with the Church, and help him die like a Christian. I told Lyovochka about this letter, and he told me I should write to Antony that his business was now with God, and to tell him his last prayer had been: “I left Thee. Now I am coming to Thee. Thy will be done.” And when I said if God sent death, then one should reconcile oneself in death to everything on earth, including the Church, he said: “There can be no question of reconciliation. I am dying without anger or enmity in my heart. What is the Church?”

The pains in his side are worse, his lungs are still inflamed, and tomorrow they will apply a plaster.

It’s foggy and cool. There is a steamer in the sea beyond Gaspra, and its sirens are hooting mournfully. The ships are all at anchor at the moment; I suppose they are afraid to move in the fog.

16th February. Lev Nikolaevich is a little better today: he is not in pain and is lying quietly; he slept much better too.

It’s extraordinary how selfless these doctors are: neither Shchurovsky nor Altschuler nor the zemstvo doctor Volkov, the poorest but kindest of them all, will accept any money; they are so generous with their time, and never begrudge the labour, the financial loss or the sleepless nights. They put a plaster on his right side today.

My head was aching this evening and it felt as if it would burst, so I lay down on the divan in Lev Nikolaevich’s room. He called out to me. I got up and went to him. “Why are you lying down?” he said. “I can’t call you if you do that.”

“My head is aching,” I said. “What do you mean, you can’t call me? You call me at night.” And I sat down on a chair. He then called to me again: “Go into the other room and lie down. Why are you sitting up?” “But I can’t leave—there’s no one here,” I said. I was terribly agitated and almost hysterical with tiredness. Masha came and I left, but then urgent tasks awaited me on all sides—business documents from the accountant in Moscow, summonses and translations, and everything had to be entered in the book, signed and sent off. Then the washerwoman and the cook had to be paid, the notes had to be sent to Yalta…

19th February. I haven’t written my diary for several days: the nursing is very hard work and leaves me little time—barely enough for housework and essential letters and business.

My poor Lyovochka is still very weak. He has been thirsty, and today drank four half-bottles of kefir. The doctors say the pneumonia is making slow progress in clearing from the right lung.

20th February. He was better yesterday; his temperature was only 37.1 and he was much more cheerful. “I see I shall now have to live again,” he said to Doctor Volkov.

“Are you bored then?” I asked him, and he said with sudden animation: “Bored? How could I be? On the contrary, everything is splendid.” This evening, concerned that I might be tired, he squeezed my hand, looked at me tenderly and said: “Thank you, darling, that’s wonderful.”

22nd February. He is much better; his temperature was 36.1 this morning and 36.6 this evening. They are still giving him camphor injections, and arsenic every other morning.

I received a letter from the orphanage suggesting I resign as patron, as I am away and cannot be useful to them. We shall see who they choose in my place and how they run their affairs.

23rd February. Another bad night. Towards evening his temperature rose to 37.4 and his pulse was 107, although it soon dropped to 88, then 89.

At night he called out to me: “Sonya?” I went in to him. “I was just dreaming that you and I were driving to Nikolskoe in a sledge together.”

This morning he told me how well I had looked after him in the night.

25th February. The first day of Lent. I yearn for the mood of peace, prayer and self-denial, the anticipation of spring and all the childhood memories that assail me in Moscow and Yasnaya with the approach of Lent.

But everything is so alien here.

Lev Nikolaevich is more cheerful, and for the first time last night he slept from 12 to 3 without waking. At 5 a.m. I went off to take a nap and he stayed awake. This morning he read the papers and took an interest in his letters. Two exhort him to return to the Church and receive the Eucharist, two beg him to send some of his works as a gift, and two foreigners express feelings of rapture and reverence. I too received a letter, from Princess Maria Dondukova-Korsakova, saying I should draw him back to the Church and give him the Eucharist.

These spiritual sovereigns expel L.N. from the Church—then call on me to draw him back to it! How absurd!

27th February. Seryozha looked after his father all night with extraordinary gentleness. “How astonishing,” Lev Nikolaevich said to me. “I never expected Seryozha to be so sensitive,” and his voice was trembling with tears.

Today he said: “I have now decided to expect nothing more; I kept expecting to recover, but now what will be will be, it’s no use trying to anticipate the future.” He himself reminds me to give him his digitalis, or asks for the thermometer to take his temperature. He is drinking champagne again and lets them give him his camphor injections.

28th February. Today he said to Tanya: “A long illness is a good thing, it gives one time to prepare for death.”

And he also said to her today: “I am ready for anything; I am ready to live and ready to die.”

This evening he stroked my hands and thanked me. But when I changed his bedclothes he suddenly lost his temper because he felt cold. Then of course he felt sorry for me.

A terrible blizzard, with one degree of frost. The wind is howling and rattling the window frames.

I spilt some ink and got it all over everything.

5th March. He is better; his temperature was 35.7 this morning and 36.7 this evening. The doctors say there is still some wheezing, but apart from that everything is normal. He has such a huge appetite he cannot wait for his dinner and lunch, and has drunk three bottles of kefir in the past twenty-four hours. Today he asked for his bed to be moved to the window so he can look out at the sea. He is still very weak and thin, he sleeps badly at night and is very demanding. He once called out five times in one hour—first he wanted his pillow adjusted, then he needed his leg covered up, then the clock was in the wrong place, then he wanted some kefir, then he wanted his back sponged, then I had to sit with him and hold his hands…And the moment one lies down he calls again.

We have had a fine day and the nights are moonlit, but I feel dead, dead as the rocky landscape and the dull sea. The birds sing outside, and for some reason neither the moon nor the birds, nor the fly buzzing at the window seem to belong to the Crimea, but keep reminding me of springtime in Yasnaya Polyana or Moscow. So the fly takes me back to a hot summer at harvest time, and the moon evokes memories of our garden in Khamovniki Street, and returning home from concerts…

6th March. Last night was frightful. Agony in his body, his legs, his soul—it was too much for him. “I can’t imagine why I recovered, I wish I had died,” he said.

8th March. I had a nasty scene with Seryozha. He shouted at a servant about Lev Nikolaevich’s new armchair: he said we should wire Odessa about it, but had absolutely no idea where or whom. I said we should first decide what kind of chair was needed. This made him lose his temper and he began shouting.

10th March. I went out for my first walk today and was astonished to see spring was here. The grass is like the grass at home in Russia in May. Various coloured primulas are in flower, and there are dandelions and dead-nettles all over the place. The sun is bright, the sea and sky are blue and the birds, sweet creatures, are singing.

Lev Nikolaevich has made a marked improvement in this fine weather—his temperature was 35.9 today and his pulse was 88. He has a huge appetite, drinks kefir day and night with great relish and reads the papers and letters. But he doesn’t seem very cheerful.

11th March. He is getting better. I went to Yalta. It was a lovely day, the sea and sky were blue, the birds were singing, the grass was springing up everywhere.

We rubbed him all over with spirit and warm water, and at ten we put him to bed.

12th March. He is slowly but surely improving. Today he read the Herald of Europe and the newspapers, and took an interest in the latest Moscow news.

13th March. It is warmer, 13 degrees in the shade, and there was a warm rain. He continues to recover. I am still sitting with him until 5 in the morning. Sasha took my place yesterday, and Tanya will do so today.

Late yesterday evening I read a translation of an essay by Emerson. It was all said long ago and much better by the ancient philosophers—that every genius is more closely connected to the dead philosophers than to the living members of his family circle. It is rather a naive conclusion.

For a genius one has to create a peaceful, cheerful, comfortable home. A genius must be fed, washed and dressed, must have his works copied out innumerable times, must be loved and spared all cause for jealousy, so he can be calm. Then one must feed and educate the innumerable children fathered by this genius, whom he cannot be bothered to care for himself, as he has to commune with all the Epictetuses, Socrateses and Buddhas, and aspire to be like them himself.

I have served a genius for almost forty years. Hundreds of times I have felt my intellectual energy stir within me, and all sorts of desires—a longing for education, a love of music and the arts…And time and again I have crushed and smothered these longings, and now and to the end of my life I shall somehow continue to serve my genius.

Everyone asks: “But why should a worthless woman like you need an intellectual, artistic life?” To this I can only reply: “I don’t know, but eternally suppressing it to serve a genius is a great misfortune.” However much one loves this man who people regard as a genius, to do nothing but bear and feed his children, sew, order dinner, apply compresses and enemas and silently sit there dully awaiting his demands for one’s services, is torture. And there is never anything in return for it either, not even simple gratitude, and there’s always such a lot to grumble about instead. I have borne this burden for too long, and I am worn out.

This tirade about the way geniuses are misunderstood by their families was provoked by my anger at Emerson and all those who have written and spoken about this question since the days of Socrates and Xantippe.

15th March. He was awake all last night with terrible pains in his legs and stomach. It’s a little warmer, the parks are slightly green, but it’s just the same old rocks, the same crooked trees, lifeless earth and tossing sea.

I did a lot of sewing today.

19th March. Life here is so monotonous, there’s nothing to write about. His illness has almost run its course.

Whenever I come into his room he is intently counting his pulse. Today he was looking through the window at the sun, poor man, and begged me to open the door of the terrace for a moment.

5th April. A lot of time has passed and little has happened. Tanya left on 30th March with her family and Andryusha arrived on the 24th. L.N.’s various treatments continue—he has been having arsenic injections since 2nd April, and today they gave him electrical treatment for his stomach. He was taking nux vomica but is now taking magnesium, and at night he has bismuth with codeine and ether-valerian drops. His nights are very disturbed, and his legs and stomach ache, so his legs have to be massaged, which I find very tiring: my back aches, the blood rushes to my head and I feel quite hysterical. He rejected all such things, of course, when his health was good, but with the onset of his first serious illness every conceivable treatment is set in motion. Three doctors visit practically every day; nursing him is extremely hard work, there are a lot of us here, we are all tired and overworked, and our personal lives have been completely eaten up by his illness. Lev Nikolaevich is first and foremost a writer and expounder of ideas: in reality and in his life he is a weak man, much weaker than us simple mortals. I couldn’t endure the thought of writing and saying one thing and living and acting another, but it doesn’t seem to bother him, just so long as he doesn’t suffer, so long as he lives and gets better…What a lot of attention he devotes to himself these days, taking his medicines and having his compresses changed, and what a lot of effort he takes to feed himself, sleep and lessen the pain.

13th April. Saturday, the evening before Easter Sunday, and my God, the depression is unbearable! I am sitting on my own upstairs in the bedroom, with my granddaughter Sonyushka sleeping beside me, while downstairs in the dining room there is the most vile heathen commotion going on. They are all playing vint, they have wheeled Lev Nikolaevich’s armchair in, and he is enthusiastically following Sasha’s game.

I am feeling very lonely. My children are even more despotic, rude and demanding than their father. Day and night, hour after hour, he attends to and cares for his body, and I can detect no spiritual feelings in him whatsoever. With me he is rude and demanding, and if I do something careless out of sheer exhaustion he shouts at me peevishly.

11th May. I am ashamed of the unkind things I wrote in my diary last time about Lyovochka and my family. I was angry about their attitude to Holy Week, and instead of being mindful of my own sinfulness I transferred my anger to my nearest and dearest. “Grant me to see my own sins and not judge my brother…”

What a long time has passed since then, and what a ghastly time we are going through once again!

He was at last beginning to recover from the pneumonia; he was walking about the house with a stick, eating well and digesting his food. Masha then suggested that I attend to my urgent business in Yasnaya and Moscow, and on the morning of 22nd April I set off.

My trip was very pleasant and successful. I spent a day at Yasnaya Polyana, where Andryusha joined me. The weather was delightful; I adore the early spring, with its soft green hues and fresh hopes for a new and better life…I busied myself with the accounts and bills, toured the apple orchards, inspected the cattle and walked over to Chepyzh as the sun was setting. The lungwort and violets were blooming, the birds were singing, the sun was setting over the felled forest, and this pure natural beauty, free of all human cares, filled me with joy.

In Moscow I was delighted by the way people treated me. Everyone was so friendly and cheerful, as though they were all my friends. Even people in the shops and banks welcomed me back warmly after my long absence.

I dealt successfully with my business, visited the Wanderers’ Exhibition* and the exhibition of St Petersburg artists, went to an examination performance of Mozart’s cheerful opera Così Fan Tutte and saw a lot of friends, and on Sunday invited a group of my closest friends to the house—Marusya, the Maklakovs, Uncle Kostya, Misha Sukhotin and Sergei Ivanovich, who played me some of Arensky’s lesser-known pieces, a Schumann sonata and his own charming symphony, which gave me more pleasure than anything.

Soothed and satisfied, I set off for Gaspra, assuming from the daily telegrams that everything there was in order. But on my return I discovered that L.N. had had a fever for the past two or three evenings, and eventually typhoid fever was diagnosed. These past days and nights have been agony and terror for all of us. At two in the morning I called on Doctor Nikitin, who is staying here with us, and he administered some strophanthus, stayed a while, then went off to bed.

Lev Nikolaevich is now lying quietly in the large gloomy Gaspra drawing room and I am writing at the table. The house is silent and ominous.

13th May. He is better, thank God. His temperature is falling steadily and his pulse has improved. Seryozha is being insufferable and keeps finding new reasons for being angry with me.

I live only for today, it’s enough for me if everything is all right. I played the piano alone for two hours in the wing while L.N. slept.

15th May. This unpleasantness with Seryozha has taken its toll. Yesterday I had such terrible pains all over my body that I thought I was dying. I am better today. L.N.’s typhus is passing; his temperature was 36.5 after his bed-bath this evening, and his pulse was 80; his maximum temperature today was 37.3. But he is weak and terribly wretched. I was told not to go downstairs but couldn’t resist visiting him. It is cold, 11 degrees.

16th May. He is much better and his temperature is down to 37, not even that. He is very bored, poor man. I should think so too! He has been ill for almost 5 months now.

He is dictating ideas about the unequal distribution of the land and the injustice of land ownership; this is his major preoccupation at the moment.* I feel I am about to break. If only I could leave!

22nd May. Lev Nikolaevich is gradually recovering: his temperature is back to normal, no higher than 36.5, and his pulse is 80. He is upstairs at present, as the downstairs rooms are being cleaned and aired. The weather is cool and rainy. Everyone in the house has become terribly homesick all of a sudden, and even L.N. is in low spirits, despite his recovery. We are all longing to be back in Yasnaya. Tanya is missing her husband, and Ilyusha his family. To be perfectly frank, all of us are feeling the need for some sort of personal life again, now that the danger is past. Poor Sasha, it’s quite reasonable for her to want this at her age.

Yesterday and today I played the piano on my own in the wing. I am practising the very difficult Chopin Scherzo (the second, in five flats). What a lovely piece it is, and how it harmonizes with my present mood! Then I sight-read the Mozart rondo (the second, the minor), such an elegant, graceful work.

I was lying in bed today wondering why a husband and wife so often find estrangement creeping into their relations, and I realized it was because married couples know every aspect of each other, and as they grow older they become wiser, and see everything more clearly. We don’t like people to see our bad side, we carefully conceal our flaws from others and show ourselves off to our best advantage, and the cleverer a person is the more able he is to present his best qualities. With a husband or wife though, this isn’t possible. One can see all the lies and the masks—and it’s not at all pleasant.

I am reading Fielding’s The Soul of a People, translated from the English. It is quite delightful. How much better Buddhism is than our Orthodoxy, and what marvellous people these Burmese are.

29th May. I haven’t written for a whole week. On Saturday the 25th Tanya went home to Kochety. On the 26th Lev Nikolaevich was carried downstairs and taken outside to the terrace, where he sat in his armchair. Yesterday he even took a spin in the carriage with Ilyusha. Professor Lamansky was here yesterday, and some peculiar fellow who talked about the low cultural level of the peasants and the necessity to do something about it. He kept saying “pardon” in French, and deliberately didn’t pronounce his “r”s. Lev Nikolaevich got very angry with him, but when I sent him away to take his pulse—which was 94 per minute—he angrily shouted at me in the presence of Lamansky: “Oh, I’m so tired of you!” which hurt me deeply.

The lovely white magnolias and lilies have come into flower.

5th June. Still in the Crimea. It is very pleasant here at the moment; the days are hot and fine and the moonlit nights are beautiful; I am sitting upstairs, admiring the reflection of the moon in the sea. Lev Nikolaevich is walking about with a stick now and seems well, although he is very thin and weak. He only lost his temper once with me yesterday, when I cut and washed his hair. He writes every morning—a proclamation to the working people, I think, and also something about the ownership of the land.

11th June. Today he went for a drive with Doctor Volkov to the Yusupovs’ Park in Ai-Todor, which he enjoyed very much. Altschuler’s wife visited, as well as Sonya Tatarinova, the Volkov family and Elpatevsky with his son. A large crowd of strangers came and peered through the window at Lev Nikolaevich.

Sofia Tolstoy in 1863

Sofia Behrs and her younger sister Tatyana, photographed some time in the early 1860s

Yasnaya Polyana, the general view of the Tolstoys’ estate, 1897

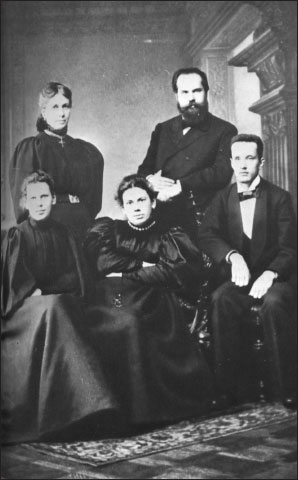

Sofia Tolstoy, Lev Tolstoy, Sofia’s younger brother Stepan Behrs, Sofia’s daughter Maria and Maria Petrovna Behrs, Stepan’s wife, 1887

Peasant women gathering apples in the Tolstoys’ orchard at Yasnaya Polyana, 1888

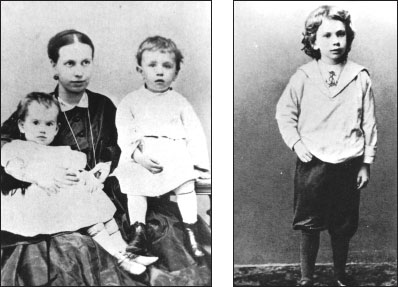

Sofia Tolstoy with her children Tatyana and Sergei, 1866 (above left), Ivan Tolstoy (Vanechka), the Tolstoys’ youngest child, photographed in 1893 in Moscow by the firm of Scherer and Nabholz (above right)

Sofia Tolstoy with her younger children: left to right, Mikhail (Misha), Andrei (Andryusha), Alexandra (Sasha) and Ivan (Vanechka)

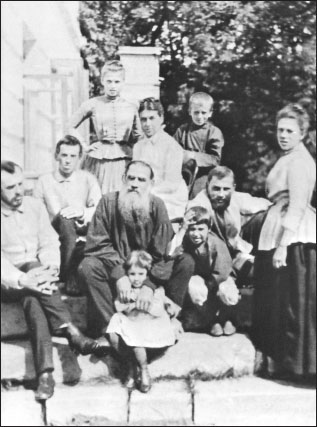

Lev and Sofia Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana, with eight of their children, 1887 (Sofia’s photograph)

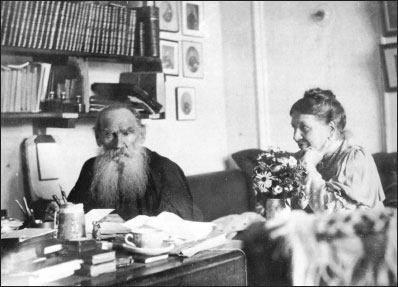

Lev Tolstoy and Sofia in his study

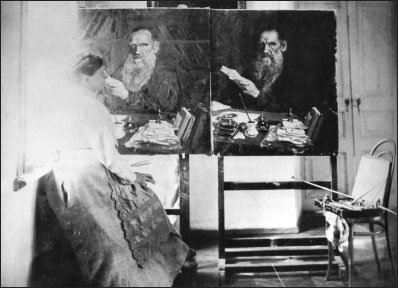

Sofia Tolstoy copying a portrait by Repin, 1904

Maria Tolstaya (Masha) haymaking at Yasnaya Polyana, 1895 (photograph by P.I. Biryukov)

Yasnaya Polyana, 1896 (Sofia Tolstoy’s photograph)

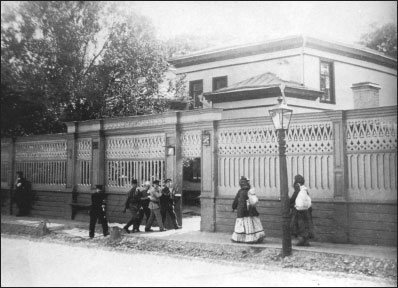

The house in Dolgokhamovnichesky Lane, Moscow

Moscow, 1896: at the back, Sofia Tolstoy and Sergei Taneev; at the front, from left to right, Maria Tolstaya, Tatiana Tolstaya, Konstantin Nikolaevich Igumnov

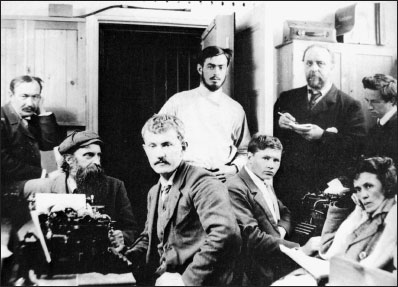

Vladimir Chertkov with colleagues at the Free Word publishing house in Christchurch, England, c.1901

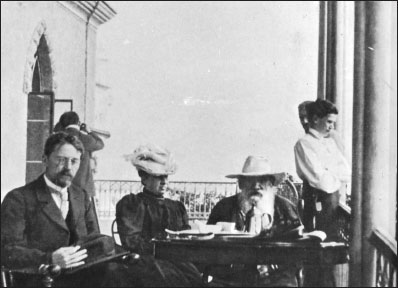

Gaspra, Crimea, 1901: left to right, Anton Chekhov, Sofia Tolstoy, Lev Tolstoy and their daughter Maria

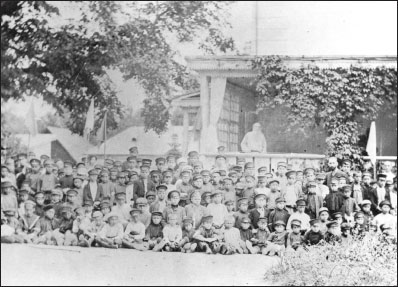

Tula schoolchildren visiting Lev Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana, 1907

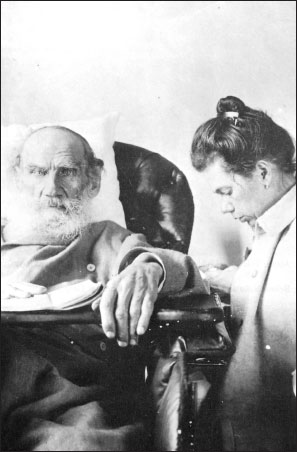

Sofia and Lev Tolstoy during his illness at Gaspra, 1901

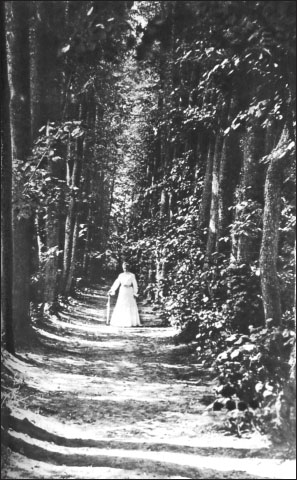

Gaspra, May 1902: Tolstoy recovering from typhoid fever, with his daughter Tatyana (Sofia’s photograph)

Sofia Tolstoy in the park at Yasnaya Polyana, 1903 (Sofia’s photograph)

Yasnaya Polyana, 1904: the Tolstoys’ eldest sons: left to right, Lev, Ilya, Sergei, Andrei and Mikhail (Sofia’s photograph)

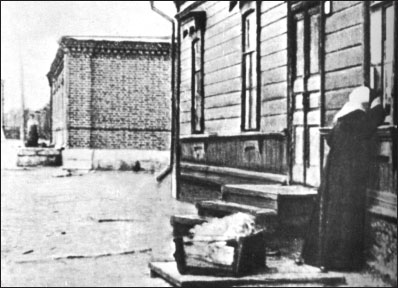

Sofia Tolstoy at the window of the stationmaster’s house at Astapovo station, where Tolstoy was dying, November 1910

Tolstoy’s sons carrying his coffin, 8th November 1910, at Astapovo station

Sofia Tolstoy by Tolstoy’s grave at Yasnaya Polyana, 1912

Sofia Tolstoy and her granddaughter Tanya, 1917

We have been enjoying life here, the weather is fine and L.N.’s convalescence is progressing well. I went riding twice, once to Orianda with Klassen and once to Alupka with him and Sasha. It was most enjoyable. I play the piano, sew and take photographs. Lev Nikolaevich is writing an appeal to the working people, ‘On the Ownership of the Land’, in which he says much the same thing as he wrote to the Tsar. We are planning to leave on the 13th.

13th June. Yet again it looks as though we won’t be leaving Gaspra for a while. In Russia it’s damp, raining and very cold—only 12 degrees—and Lev Nikolaevich has an upset stomach.

He is still writing his proclamation to the workers. I copied the whole thing for him today. Much of it is illogical, impractical and unclear. The fact that the land is owned by the rich, and the great suffering this imposes on the peasants, is indeed a crying injustice. But this matter will not be resolved in a hurry.

17th June. Arguments about the Bashkirs.* Numerous visitors milling around all day.

26th June. Yesterday we finally left Gaspra. I thank God He has granted us to take Lev Nikolaevich home once more! I pray he never has to leave again!

27th June (Yasnaya Polyana). Today we returned home from the Crimea. We rode to Yalta on horseback, with Lev Nikolaevich and Sasha, travelling in the Yusupovs’ rubber-tyred carriage. There were Lev Nikolaevich, Sasha and I, my son Seryozha, Boulanger, Yulia Igumnova and Doctor Nikitin in our party. In Yalta we boarded the steamer Alexei. Ladies, bouquets, crowds of people waving farewell…On the steamer L.N. sat on deck, ate in the public dining room and felt extremely well…In Sevastopol we disembarked onto a skiff and sailed round the harbour to the station; the sun was bright and it was very beautiful. A specially large, comfortable carriage with a saloon had been set aside for L.N. Sasha was ill and miserable and had an upset stomach. At Kharkov station, people—mostly women—welcomed him with ovations. At Kursk there were crowds of people who had just been to an exhibition on popular education. The police pushed them back, and deputations of men and women teachers and students boarded the train—Misha Stakhovich, Dolgorukov, Gorbunov and Lodyzhensky, among others.

It was a joy to get back to Yasnaya, but our joy was short-lived. That evening Masha began to have pains, and soon afterwards she gave birth to a dead baby boy.

30th June. Lev Nikolaevich had a temperature of 37.8 this evening and we were very anxious about him. I sat with Masha all morning. It is cold and raining. The saffron milk caps* are out.

3rd July. Lev Nikolaevich walked to the side wing to see Masha, and this afternoon he played Haydn’s second symphony as a duet with Vasya Maklakov. Sasha brought in some saffron milk caps.

4th July. Lev Nikolaevich is well; he went to the side wing and back. This afternoon he had a long talk with Doctor Nikitin about psychiatrists, whom he was criticizing.

23rd July. The time is passing terribly fast. On 5th July I went to see Ilyusha at Mansurovo, his estate in the province of Kaluga, and spent a delightful two days with him, Sonya and my grandchildren. We went for walks and drives through the lovely woods and countryside, and had long heart-to-heart talks.

On 7th July, I went to Begichevka to see Misha and my lovable little grandson Vanechka. Lina is a sensitive, serious, loving woman. Misha is young and arrogant, but this will pass. On the night of the 8th I returned to Yasnaya with Misha. Lev Nikolaevich is well but weak. Sasha had a nervous attack on the 10th.

On 11th July, Sasha and I went to Taptykovo to visit Olga on her name day. We had a pleasant day, and returned home late that night after a heavy downpour of rain.

My son-in-law Mikhail Sukhotin is gravely ill with suppurative inflammation of the lung. I felt so anxious and so sad for poor Tanya, and on the evening of 16th July I set off for Kochety. The atmosphere there was cold and depressing. Mikhail Sergeevich looked thin and wretched, and Tanya, who had been sitting up with him every night, was tense and exhausted. I spent four days there and returned on the morning of the 21st.

It is still cool, and yesterday it poured with rain. The rye still hasn’t been sheaved and the oats aren’t cut. It is afternoon now, and only 10 degrees. Before it rained yesterday I took a drive round Yasnaya Polyana and the plantations. How wonderfully beautiful it all is!

26th July. A full and happy day. Ilya’s family came with Annochka and the grandsons, and we took a walk with Zosya Stakhovich and Sasha. This evening Goldenweiser played beautifully, a Schumann sonata and a Chopin Ballade. Then we talked about poets and Lev Nikolaevich recalled Baratynsky’s poem ‘On Death’. We straight away got out the book and Zosya read us this lovely poem.

On the 22nd another son was born to Lyova and Dora; we had a telegram from them today.

Lev Nikolaevich is well. He played vint all evening and enjoyed the music. In the mornings he writes his novel Hadji Murat,* to my great delight.

27th July. Music continues to have its usual healing effect on me. This evening Goldenweiser played, excellently, the Chopin sonata with the funeral march. L.N. was sitting near me and the room was filled with my nearest and dearest—Ilyusha, Andryusha, Sonya, Olga, Annochka, Zosya Stakhovich and Maria Schmidt. And moved by the music, I felt a quiet joy creep into my heart and fill it with gratitude to God for bringing us all together once more, happy and loving, and for allowing Lev Nikolaevich to be with us still, alive and comparatively well…And I felt ashamed of my weaknesses and resentments and all the evil that spoils this good life of mine…

9th August. What a long time it is since I wrote my diary! The past month has been filled with anxieties about Sukhotin’s health; he is now worse again. My poor darling Tanya. She loves him too much, and is finding it very hard; nursing him is difficult enough as it is. I went to Moscow on the 2nd and was busy checking accounts, attending to business and ordering the new edition. Sergei Ivanovich is immersed in work on a musical textbook* that he wants to finish before leaving for Moscow. I asked him to play something, but he refused, and was stern, unapproachable and even rather unpleasant. There is something sad and serious about him nowadays; he has aged and changed, and this makes me unhappy. I was glad to get home. Lina came yesterday with little Vanechka, and this morning Misha arrived. His whole family is utterly charming in every respect. Lina’s mother came yesterday with her sister Lyuba. My nephew Sasha is here, and Annochka and Maude, and Liza Obolenskaya arrived. A lot of commotion, but most enjoyable.

Lev Nikolaevich played a game of vint and asked for something to eat. He is still writing his story Hadji Murat, and today his work evidently went badly, as he played patience for a long time—a sure sign he can’t work something out. The priests keep sending me religious books which curse him.* Neither he nor they are right; all extremes lack the wisdom and goodness of inner tranquillity.

A grey day, but no wind. A bright sunset and a moonlit night.

11th August. Misha’s family left yesterday, and Olga arrived with Sonyushka. What a sweet, affectionate, clever little girl she is! I love her so much. Liza Obolenskaya left, and Stasov arrived, and also Ginzburg, who has sculpted a bas-relief of Sasha which is very bad and not at all like her. I have now learnt how to do this myself, and would very much like to attempt a medallion of L.N. and me.

We all went to pick saffron milk caps yesterday; I left the others and had a lovely time wandering through the forest on my own. The old fire in my heart is extinguished, and I am obviously growing old.

Lev Nikolaevich has been very lively and talkative. He told us when he was in Sevastopol he had asked to be assigned a post, and they sent him and the artillery to the fourth bastion. But he was removed from there on the Tsar’s orders, after Nicholas I sent Gorchakov a message saying: “Remove Tolstoy from the fourth bastion and spare his life, for he is worth something.”

Rain all day. The oats are still in the field. 13 degrees.

28th August. Lev Nikolaevich’s 74th birthday. We went out to meet him on his way back from his walk. Four of our sons have come; Lyova is in Sweden, and my poor darling Tanya couldn’t be here as her husband is still ill. We celebrated my great husband’s birthday in the most banal fashion: dinner for twenty-four illassorted people, with champagne and fruit, and a game of vint afterwards, just like any other day. Lev Nikolaevich simply cannot wait for evening, when he can sit down to a hand of vint. And they have now dragged Sasha into their games, which greatly distresses me.

He is working hard on Hadji Murat.

2nd September. On 31st August two doctors arrived from Moscow for a consultation—capable, lively Shchurovksy and P. Usov, a dear cautious man who has treated L.N. before. They both decided it would be best to spend the winter here in Yasnaya, which is far more to my liking than having to travel here, there and everywhere. I personally find it much easier in Moscow; there are people I love there, and a lot of music and serious innocent entertainments—exhibitions, concerts, lectures, interesting friends, social life and so on. But I realize Lev Nikolaevich finds Moscow insufferable, with all the visitors and noise, so I shall gladly live in my dear Yasnaya and visit Moscow only when I am exhausted here.

Meanwhile life is very eventful, time speeds past, I am kept busy all day long, and there isn’t any music or a chance to rest. All these guests can be very tiresome at times. I have started to sculpt a medallion of L.N.’s and my profiles. I’m in despair that I won’t be able to finish, but I do so want to; I occasionally sit up all night, as late as 5 a.m., straining my eyes.

10th October. I haven’t written for so long—time has flown. On 18th September I saw my Tanya and her family off to Montreux in Switzerland. My heart ached to see her, wretched, pale and thin, bustling about on the Smolensk station with all the luggage and her sick husband. But we have just had good news from her, thank God.

I spent my name day in Moscow. I invited a lot of guests, who came to say goodbye to the Sukhotins, and Sergei Ivanovich, whom I had run into on the street. He was solemn and austere; something in him has changed, he has become even more impenetrable than before.

At 11 o’clock on 11th September we had a fire in the attic and four beams were burnt. By a sheer stroke of luck I had gone up to inspect the attic and noticed the fire. If I hadn’t, the whole house would have burnt down and the ceiling might have collapsed on top of Lev Nikolaevich, who was asleep in the room directly below. I was led there by the hand of God, and I thank Him for it.

Lev Nikolaevich’s health is good; he went horse-riding, worked on Hadji Murat and has started on a proclamation to the clergy.* Yesterday he said: “How hard it is. One must expose evil, yet I don’t want to write unkind things as I don’t want to arouse bad feelings.”

But our peaceful life here and our good relations with our daughter Masha and her shadow—her husband Kolya—have now been disrupted. It is a long story.

When the family divided up the property, at Lev Nikolaevich’s insistence, our daughter Masha, who had already reached the age of consent, refused to partake of her parents’ inheritance. As I didn’t believe her at the time, I took her share in my name and wrote my will, leaving this capital to her. But I didn’t die, and then Masha married Obolensky and took her share, as she had to support both herself and him.

But as she had no rights in the future, she decided without telling me to copy out of her father’s diary for 1895 a whole series of his wishes after his death. Among other things, he had written that it made him unhappy that his works should be sold, and that he would prefer his family not to sell them after his death. When L.N. was dangerously ill last July, Masha asked her father, without telling anyone, to sign this passage she had copied from his diary, and the poor man did so.

It was exceedingly unpleasant for me when quite by chance I found out about it. To make L.N.’s works common property would be senseless and wicked, in my opinion. By making his works public property we only line the pockets of rich publishing companies like Marx, Zetlin and so on. I told L.N. that if he died before me I would not carry out his wishes and would not renounce the copyright on his works; if I thought that was the right and proper thing to do, I would give him the pleasure of renouncing it during his lifetime, but there was no point in doing so after his death.

As I didn’t know the exact contents of this document, I asked Lev Nikolaevich to give it to me, after he had taken it from Masha.

He readily agreed, and handed it over to me. Then Masha flew into a rage. Yesterday her husband was shouting God knows what nonsense, saying they had planned to make the document “public property” after Lev Nikolaevich’s death, so as many people as possible would know that he hadn’t wanted to sell his works, but his wife had made him do so.

So the upshot of this whole episode is that Masha and Kolya Obolensky will now be leaving Yasnaya.

23rd October. Masha and I have made peace; she has stayed on in the side wing at Yasnaya, and I am very glad.

An unbearably muddy, cold, damp autumn. It snowed today.

Lev Nikolaevich has finished Hadji Murat and we read it today; the strictly epic character of the story has been very well sustained and there is much artistic merit in it, but it doesn’t move me. We have only read half of it though, and will finish it tomorrow.

4th November. It is very frosty; the little girls are skating. The sun is bright, the sky is blue, and as I came up the avenue to the house I had a sudden vivid memory of the distant past, walking up this same avenue from the skating rink carrying a baby on one arm, shielding him from the wind and closing his little mouth, while the other dragged a child in a sledge, and behind us and before us were happy, laughing red-cheeked children, and life was so full and I loved them so passionately…And Lev Nikolaevich came out to meet us, looking healthy and cheerful, having spent such a long time writing that it was too late for him to go skating…

Where are they now, those little children whom we reared with such love? And where is that giant—my strong, cheerful Lyovochka? And where am I, as I was in those days? If only I could live a little better and not store up so much guilt towards people, especially my family.

8th November. Yesterday the sun shone, we were all in high spirits and I went skating with the little girls—Sasha, Natasha Obolenskaya and their young pupils. We all had a fine time on the ice. Today we had a discussion about divorce. I said divorce was sometimes necessary, and cited the case of L.A. Golitsyna, whose husband abandoned her three weeks after the wedding for a dancing girl, and whom he told quite cynically he had only married in order to have her as his mistress, otherwise he would never have managed to get her.

Lev Nikolaevich replied that marriage was merely the Church’s seal of approval on adultery. I retorted that this was only the case with bad people. He then snapped back in the most unpleasant way that it was so for everyone. “What about in reality?” I said. To which he replied, “The moment I took a woman for the first time and went with her, that was marriage.”

And I had a sudden painful insight into our marriage as Lev Nikolaevich saw it. This naked, unadorned, uncommitted sexual coupling of a man and a woman—that is what he calls marriage, and after that coupling it doesn’t matter to him who he has gone with. And when he started saying one should only get married once, to the first woman one fell with, I grew extremely angry.

It is snowing, and there seems to be a path in the snow. I looked through the proofs of The Cossacks. What a well-written story, what brilliance, what talent. A man of genius is always so much better in his works than in his life!

25th November. I feel more and more lonely here in the company of those members of my family I still have with me. Today I returned from Moscow to find that Dr Elpatevsky had just arrived from the Crimea, and this evening L.N. read him a legend he has just written, about devils.*

This work is imbued with the most truly negative, malicious, diabolical spirit, and sets out to mock everything on earth, starting with the Church. The supposedly Christian feelings that L.N. puts into these discussions among the devils are presented with such coarse cynicism it made me sick with rage to hear him read it: I became feverish, and felt like weeping and shouting and stretching out my hands to ward off the devils.

I told him in no uncertain terms how angry it made me. Would it not be more fitting for an old man of seventy-five, whom the whole world respects, to do like the Apostle John, who when he was too weak and debilitated to speak simply said, “Children, love each other!” Neither Socrates, Marcus Aurelius, Plato nor Epicurus had any need to attach ears and devils’ tails to the truths they wanted to proclaim. But then maybe contemporary man, whom L.N. is so clever at pleasing, needs this sort of thing.

And my children too—Sasha, who is too young to know better, and Masha, who is a complete stranger to me—both imitated their father’s laugh with their own hellish laughter after he had finished reading his devilish legend, and I felt like sobbing. Did he have to survive death to do work like this!

7th December. My soul is again filled with despair and the terror of losing my beloved husband! Help me, Lord…Lev Nikolaevich has a fever—39 this morning—his pulse is weak, his strength is failing…The only doctor who has seen him cannot understand what is wrong.

We have summoned Dreyer from Tula and Shchurovsky from Moscow, and are expecting them today. We have wired our sons too, but none of them has arrived yet.

While there is still hope and I still have the strength, I shall write down everything that has happened.

When Lev Nikolaevich was having lunch I came in and sat with him. He ate porridge and semolina with milk, and asked for some curd pancakes from our lunch, which he ate with the semolina. I remarked that these pancakes were a little heavy for him while he was drinking Karlsbad—which he has been taking for four weeks now—but he wouldn’t listen.

After lunch he set off for a walk on his own, and asked to be driven to the highway. I assumed he would take his usual walk along the main road, but without saying a word he set out for Kozlovka, turned off into Zaseka—3 miles in all—then put on a frozen fur coat over his sheepskin jacket and drove home, flushed and exhausted, in a cold north wind and 15 degrees of frost.

The following morning, 5th December, about midday, he felt chilled and wrapped himself in his dressing gown, but remained at his desk with his papers all morning and ate nothing. He went to bed in the afternoon and his temperature went up to 38.8. That night he started having bad stomach pains; I stayed with him all night and kept his stomach warm. That evening he had a temperature of 39.4, but then Masha suddenly ran in, beside herself, and said, “His temperature is 40.9!” We all looked at the thermometer, and sure enough it was—although I am still not sure there wasn’t something wrong with the mercury. We were all distraught; we sponged him down with alcohol and water, and when we took his temperature it was 39.3 again.

I am going in to Lyovochka again—oh, these groans, how I suffer for him…Forgive me, my darling, God bless you!

8th December. His temperature has gone down now and the fever has passed in a profuse sweat. But his heart is still weak. The doctors have diagnosed influenza and now fear these bacteria may lead to pneumonia.

We had a visit this morning from those two dear selfless doctors, always so bright and kind—warm-hearted Usov and cheerful Shchurovsky. Doctor Chekan from Tula stayed the night here and our own Doctor Nikitin has been kind, sensible and diligent.

Seryozha, Andryusha and his wife and Liza Obolenskaya arrived yesterday, and Ilya arrived today.

I looked after Lev Nikolaevich until five this morning, when Seryozha took my place. The doctors also took turns—first Nikitin, then Chekan.

12th December. It is now six in the morning of 12th December. I have spent another night sitting beside Lyovochka’s bed and can see him slipping away.

A cheerless life looms ahead.

Long sleepless nights, with a heart full of anguish, a terror of life and a dread of living without Lyovochka.

As I was leaving the room just now he said, “Goodbye, Sonya!” in a distinct and significant tone of voice. And I kissed his hand and said “Goodbye” to him too. He thinks I might be asleep when he dies…No, he doesn’t think anything of the sort, he understands everything, and it’s so hard for him…

13th December, evening. Lyovochka has come back to life again and is much better—his pulse, temperature and appetite have improved. Boulanger was reading Kropotkin’s Notes* to him.

Today the following announcement from Lev Nikolaevich appeared in the Russian Gazette:

We have received this letter from Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy:

Dear Sir, Most Honoured Editor,

Due to my extreme age and the various illnesses which have taken their toll, I am obviously not in particularly good health, and this deterioration in my condition will naturally continue. Detailed information about this deterioration may be of interest to some people—and in completely opposite senses too—but I find the publication of this information most unpleasant. I would therefore ask all newspaper editors not to print information about my illness.

Lev Tolstoy, 9th December, 1902

18th December. Lev Nikolaevich is still in bed. He sits up, reads and takes notes, but is very weak…

I have been reading Hauptmann’s The Weavers: all we rich people, landowners and manufacturers live such extraordinarily luxurious lives, I thought; I often don’t go to the village simply to avoid the awkwardness and shame I feel for my wealthy, privileged life and their poverty. Yet I am constantly astonished at how meek and gentle they are with us.

Then I read some of A. Khomyakov’s poems. There is so much genuine poetry and feeling in them. ‘To Children’ simply pours from his heart, honest and passionate. If one has never had children, one couldn’t possibly understand the feelings of a parent, especially a mother.

You go into the nursery at night and look at the three or four little cots with such a feeling of fullness, richness and pride…You bend over each one of them, look into those lovely innocent little faces which breathe such purity, holiness and hope. And you make the sign of the cross over them or bless them in your heart, then pray for them and leave the room, your soul filled with love and tenderness, and you ask nothing of God, for life is full.

And now they have all grown up and gone away…And it’s not the empty cots that fill one with sadness, it’s the disappointment in those beloved children’s characters and fates.

27th December. It’s again a long time since I have written. I spent three days in Moscow—the 19th, 20th and 21st. I got the accounts for the book sales from the accountant, did some shopping and got presents for the children, servants and so on, which they loved.

Lev Nikolaevich improved greatly while I was away, and got up, went into the next room and worked. Then on Christmas Day he suddenly grew worse. He ate nothing, was given strophanthus and caffeine, and the doctor was evidently nonplussed. Yesterday he was much better again.

When Lev Nikolaevich was so ill, he said half-joking to Masha, “The Angel of Death came for me, but God called him away to other work. Now he has finished he has come for me again.”

Every deterioration in Lev Nikolaevich’s condition causes me greater and greater suffering, and I am terrified of losing him. In Gaspra I didn’t feel nearly so much pain and tenderness for him as I feel now. What agony it is to see him suffering and sinking, weak and stricken in mind and body!

I take his head in my hands and kiss him with tender love and solicitude, and he looks at me blankly.

What is happening to him? What is he thinking?

29th December. First Lev Nikolaevich gets better, then worse. Today he said to me: “I am afraid I shall be exhausting you for a long time.”

We talked about the English. Two Englishmen from some spiritual society had walked to London dressed only in jackets and open shirts, and from there they travelled to Russia without so much as a kopeck, with the sole purpose of seeing Tolstoy and asking him to clear up their religious doubts. They stayed with Dunaev, and we sent a couple of L.N.’s fur coats and caps over to them so they wouldn’t freeze.