One

PIONEERS

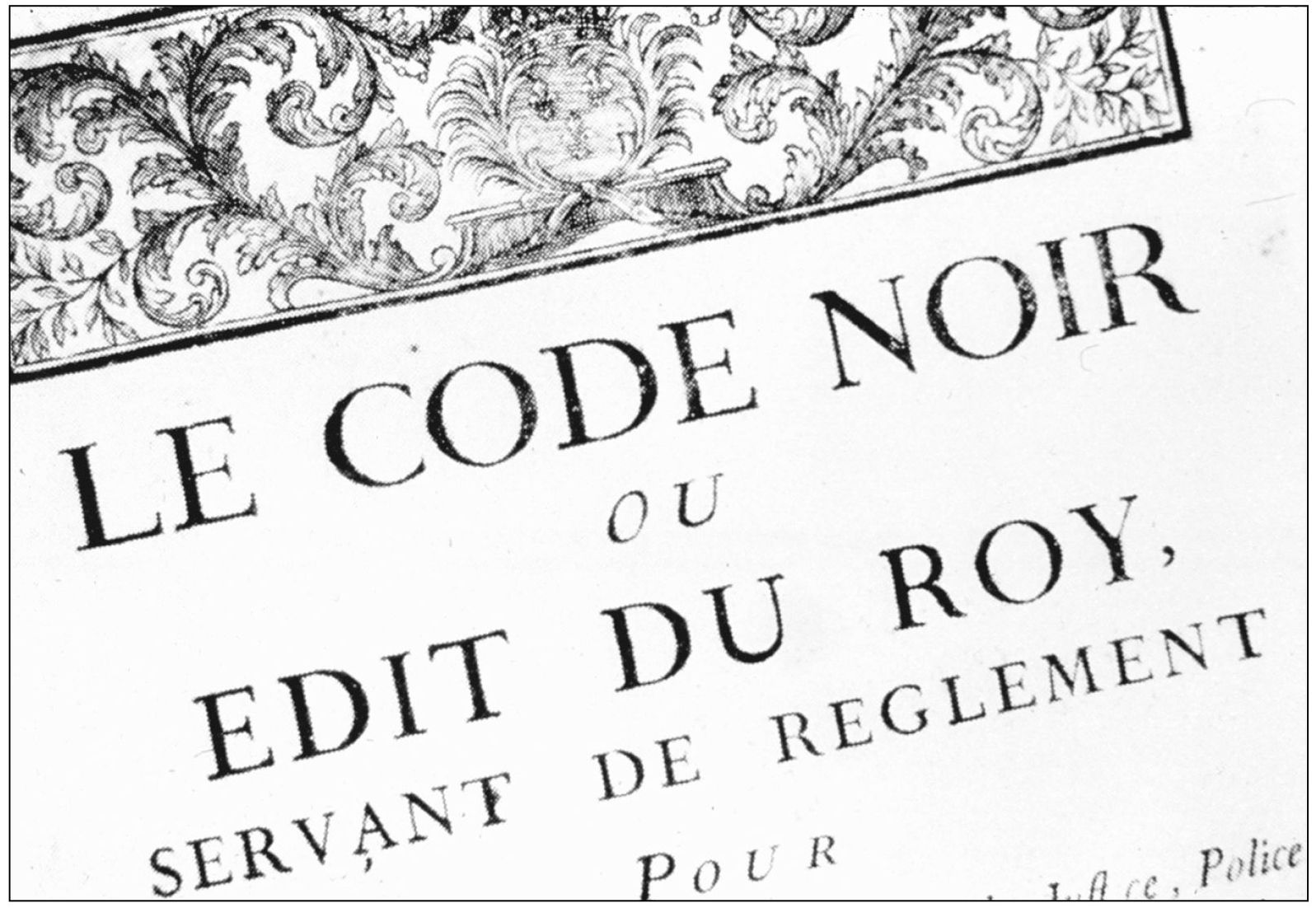

La Code Noir, or the Black Code, of 1724 was promulgated by the French crown to establish “what concerns the state and condition of the slaves” in the Louisiana territory. However, the first article proclaimed that “all Jews who may have established their religion there be expelled within three months under penalty of confiscation of body and property.” This restriction was never enforced during French colonial rule.

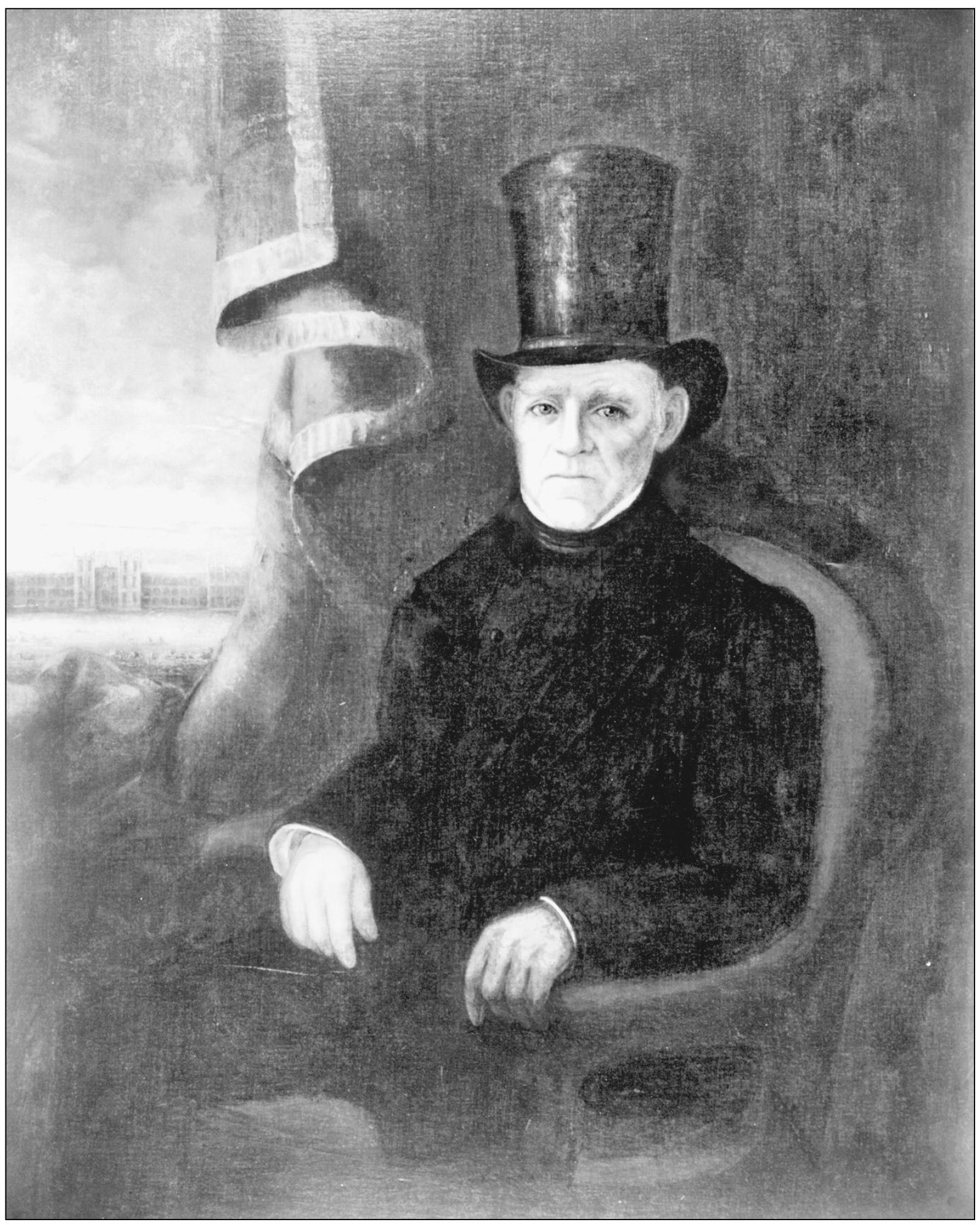

Shown here is Angelica Monsanto Dow (1744?–1821). This is the only portrait of a member of the first Jewish family to permanently settle in New Orleans. Her brother, Isaac, arrived in 1757, and over the next few years three brothers and three sisters, including Angelica, joined him. In 1769, the family was expelled and their property confiscated by the Spanish, Governor O’Reilly citing the Code Noir—which prohibited Jews in Louisiana—as the reason for expulsion. The family moved to Pensacola, where Angelica married a Scottish Protestant, George Urquhart, and became a devout Protestant. The Urquharts eventually returned to New Orleans and became prominent members of New Orleans society. Their eldest son, Thomas, was a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives and an officer of the United States Bank in New Orleans. After Urquhart’s early death, Angelica married another Scottish Protestant, Dr. Robert Dow.

Judah Touro (1775–1854) was the son of Isaac Touro, the hazan, or minister-cantor, of Congregation Yeshuat Yisroal in Newport, Rhode Island. After his father’s death in Jamaica in 1783, young Judah, along with his mother, brother, and sister, moved to Boston where, at the age of eight, he became an apprentice to his mother’s brother, Moses Michael Hays, a successful businessman. In 1802, Touro abruptly left Boston, eventually making his way to New Orleans, where he slowly but surely made his fortune as a commission merchant and in real estate, owning much of what is today the downtown section of the city. After suffering a near fatal injury in 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans, he was a virtual recluse the last 40 years of his life. His will left money to almost every Jewish organization in the United States, as well as an almshouse in Jerusalem.

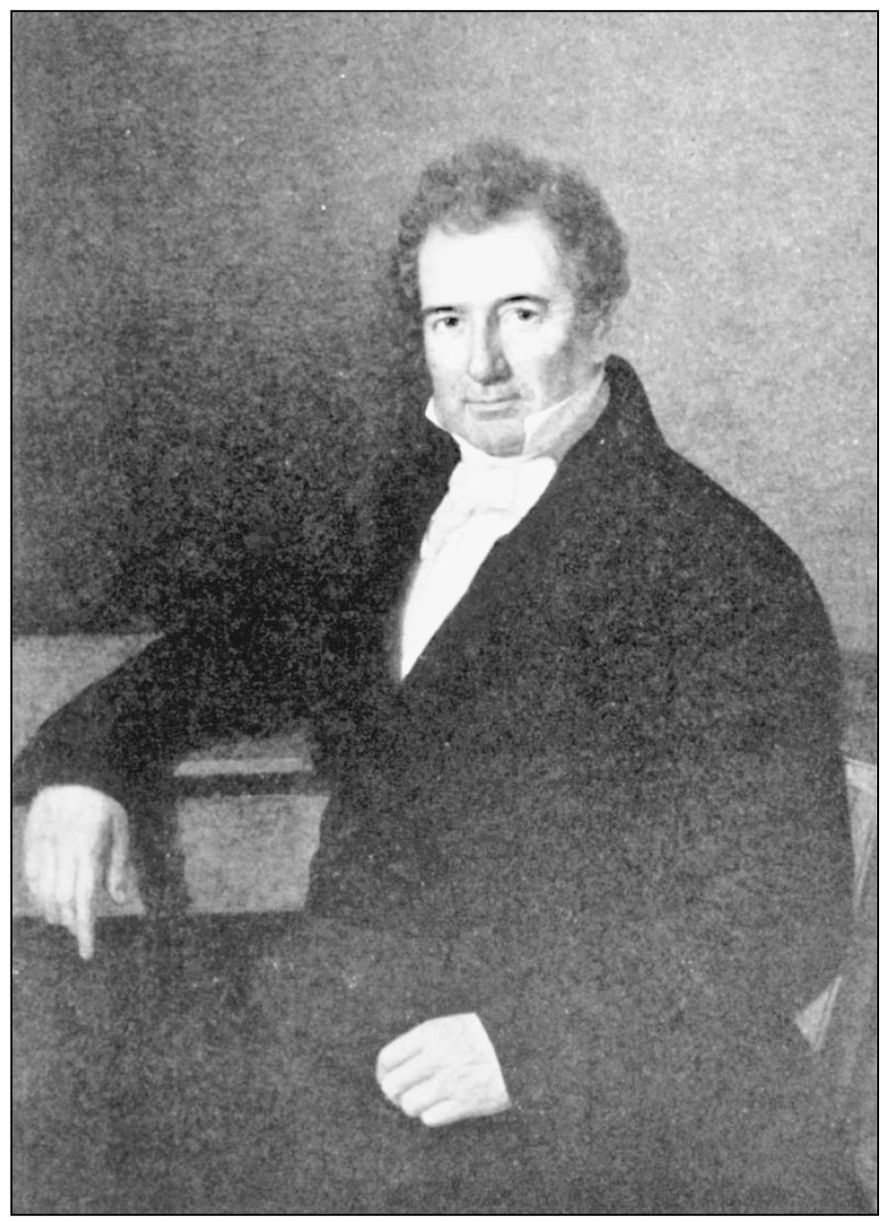

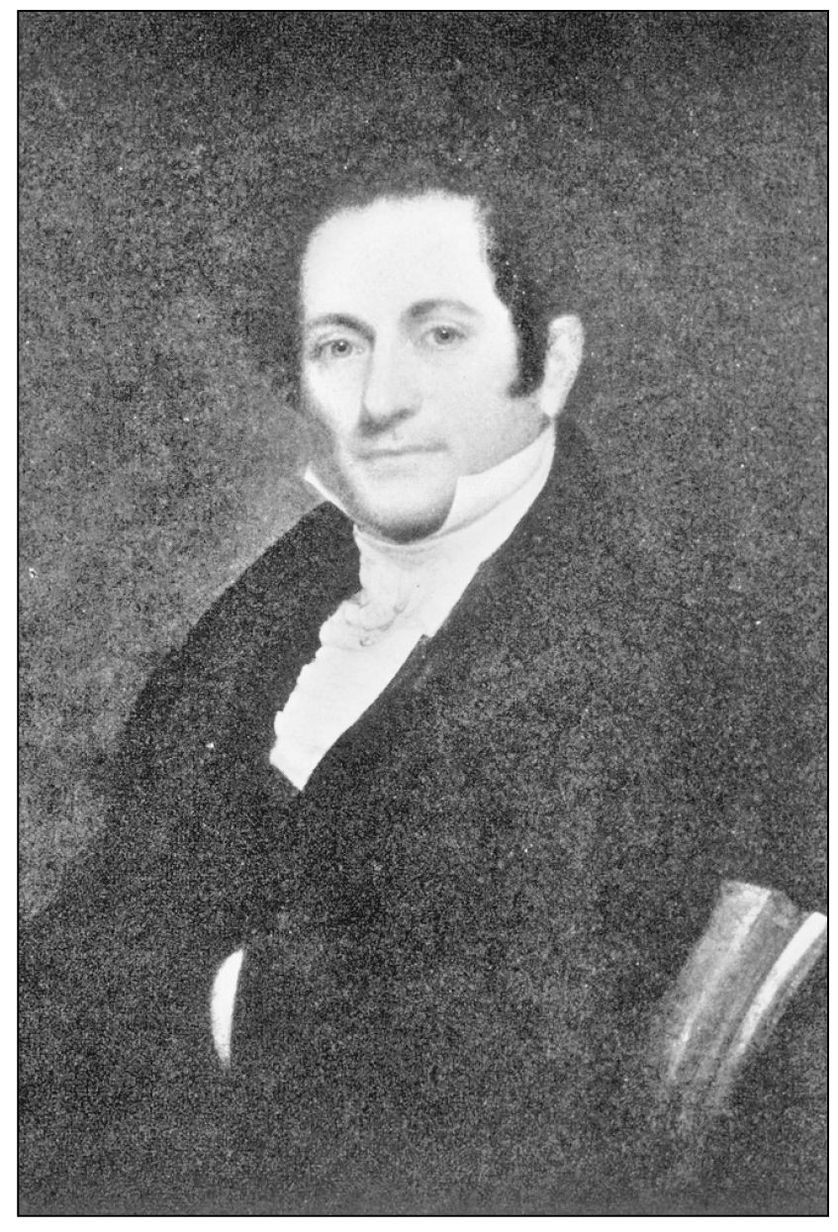

Samuel Hermann (c. 1777–1853) was born in Roedelheim, Germany. He arrived in Louisiana around 1805, settling just along the German Coast in Saint John Parish. In 1806, he married a Catholic widow, Marie Emeronthe, with whom he had three sons and a daughter. By 1813, he was in the city, acting as a merchandise agent and personal banker with financial interests throughout the United States and Europe.

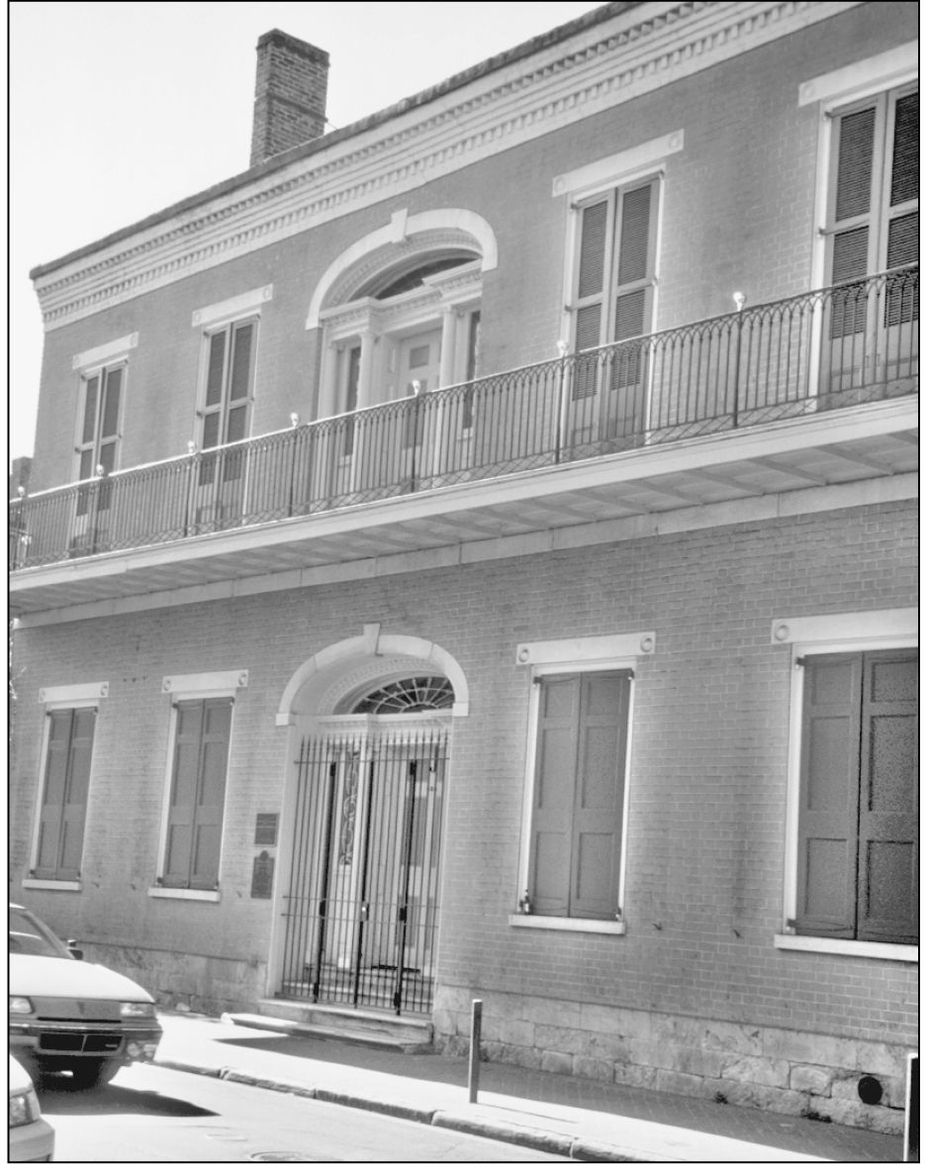

In 1823, Samuel Hermann bought the home at 820 St. Louis Street. Eight years later, he tore down the existing property and built one of the showpiece homes of the city, renowned for the grand soirees that occurred there. Financial difficulties forced him to sell the home in 1841. Eventually the house was bought by the notary Felix Grima. Today the home is a museum, the Hermann-Grima House.

Samuel Kohn (1783–1853) was born in the village of Hareth, Bohemia, and wasted his youth drinking and gambling. One day he lost so much money gambling that he was too embarrassed to go home and explain to his parents. He left, telling no one, and finally made his way to New Orleans some time around 1806. He opened an inn on Bayou St. John, offering drinking, gambling, and loans to partake in the games. Soon he opened a bank and became a leading real-estate developer. He retired to Paris in 1832.

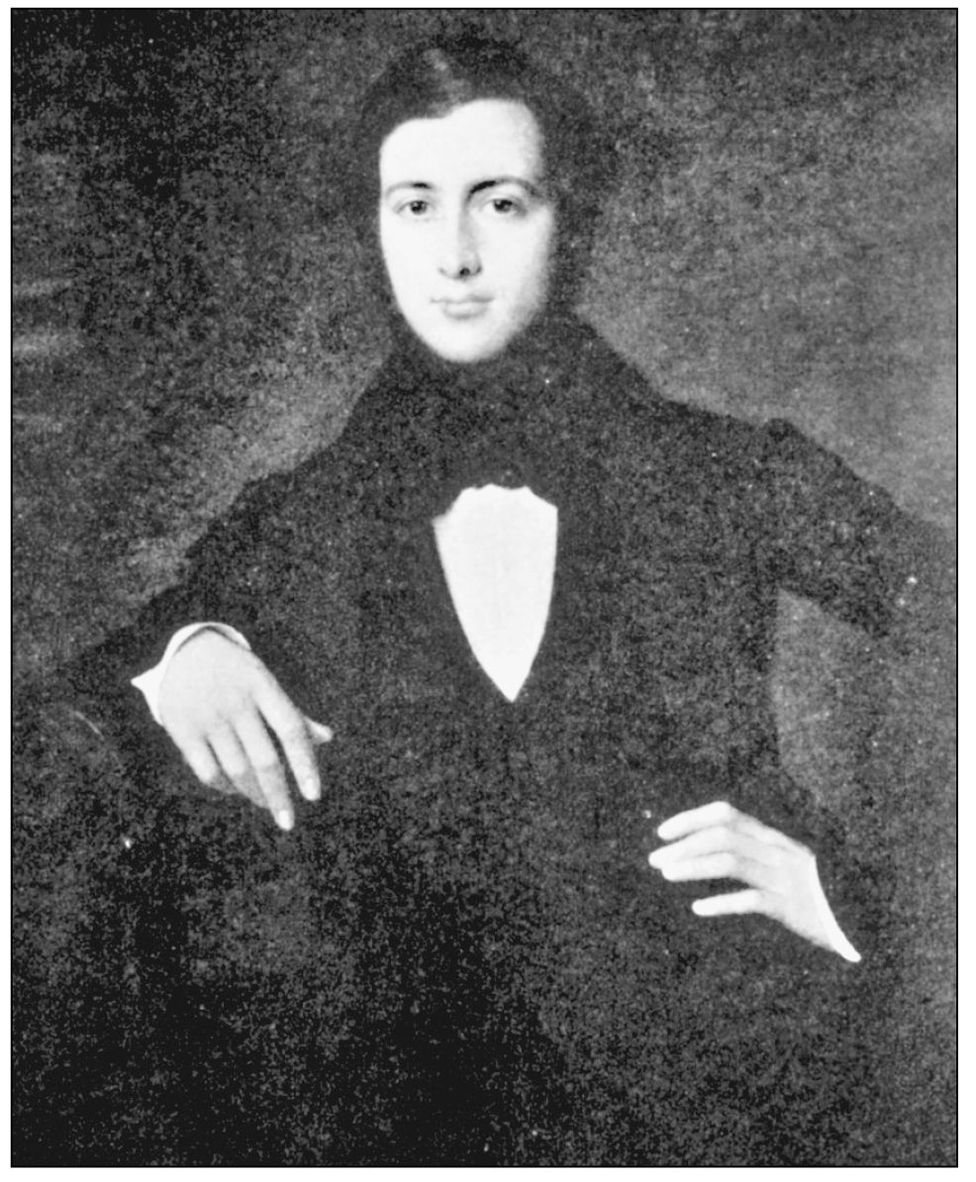

Carl Kohn (1815?–1895) was brought to New Orleans by his uncle Samuel in the early 1830s. Without any formal education, he quickly taught himself English, French, and Spanish. Through his uncle he gained access into the finest society, and in 1850 he married Clara White, daughter of Maunsel White, the wealthiest man in the city. Among Kohn’s many business enterprises were the Atlantic Insurance Company and the Union National Bank. He died in 1895, “one of New Orleans’ most respected citizens.”

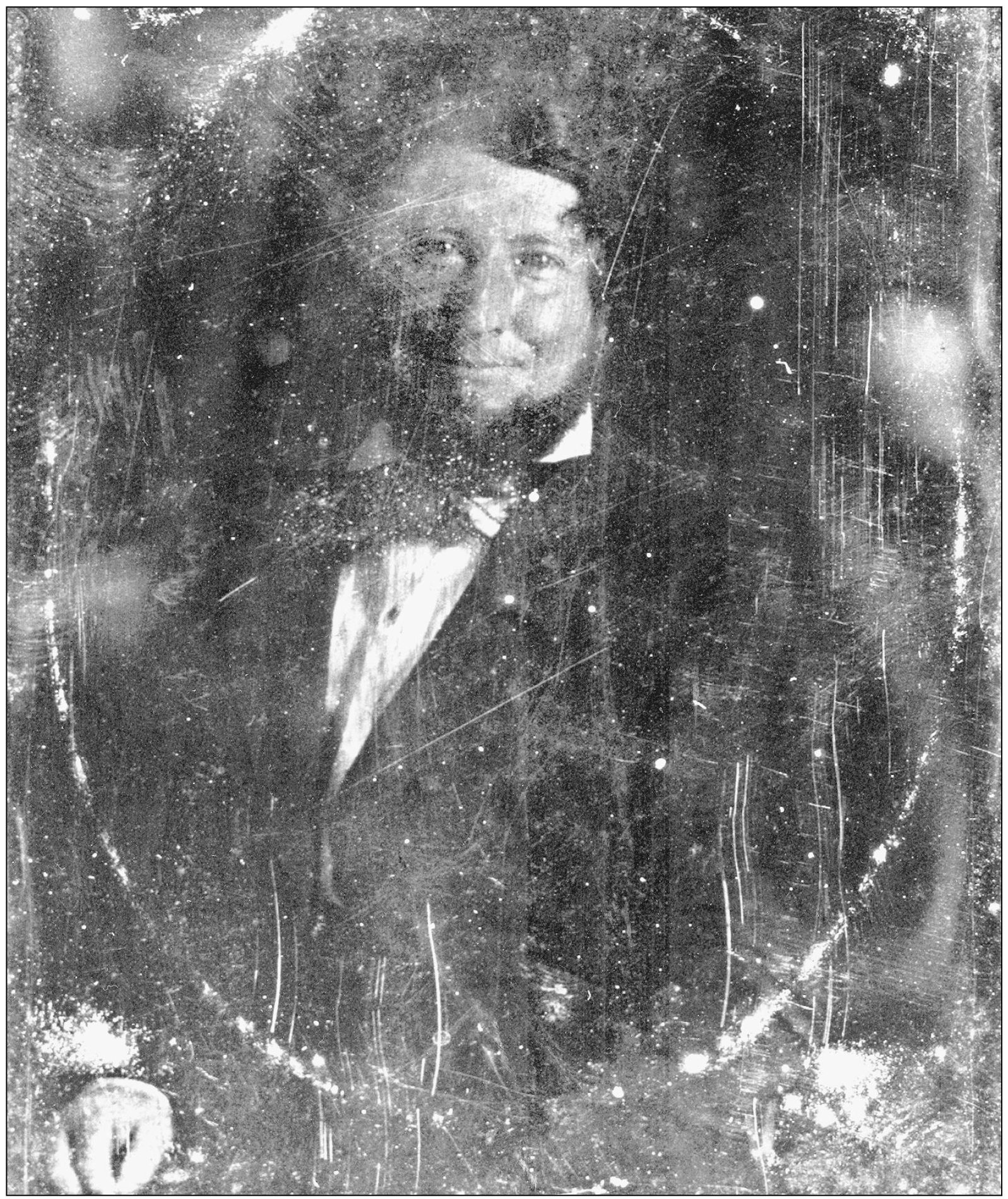

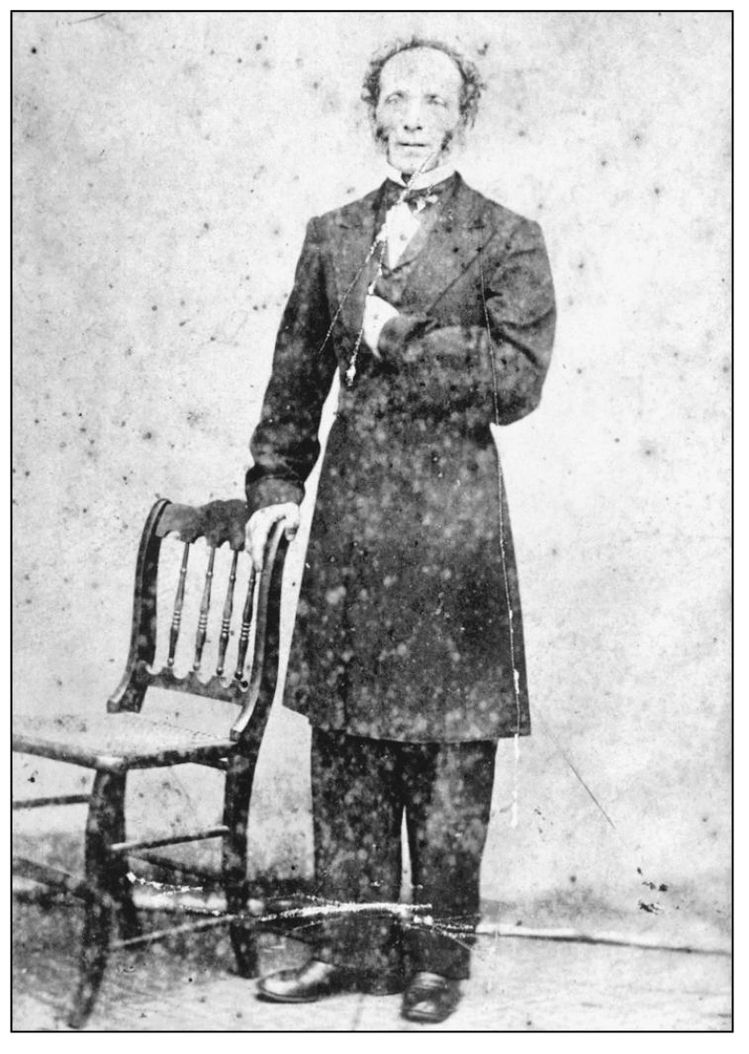

Judah P. Benjamin (1811–1884), the “brains of the Confederacy,” arrived in New Orleans in 1827 and began reading the law in preparation for becoming an attorney. After a successful 10 years in practice, Benjamin began a sugar plantation just below the city, which he named “Bellechasse.” He was elected to the United States Senate in 1852, the first avowed Jew elected to that body. He was nominated for a seat on the United States Supreme Court the following year, but he turned the nomination down, preferring the hustle and bustle of the legislative body. In the Senate, his was a leading voice in the cause of Southern rights, and he proudly joined the Confederate Cabinet. As the war ended, he made a harrowing escape to London, where he once again took up the law. He never returned to the United States. He died in Paris in 1884, his wife having had a priest administer the Catholic last rites. The above image is a heretofore unpublished daguerreotype of Benjamin taken sometime in the 1850s.

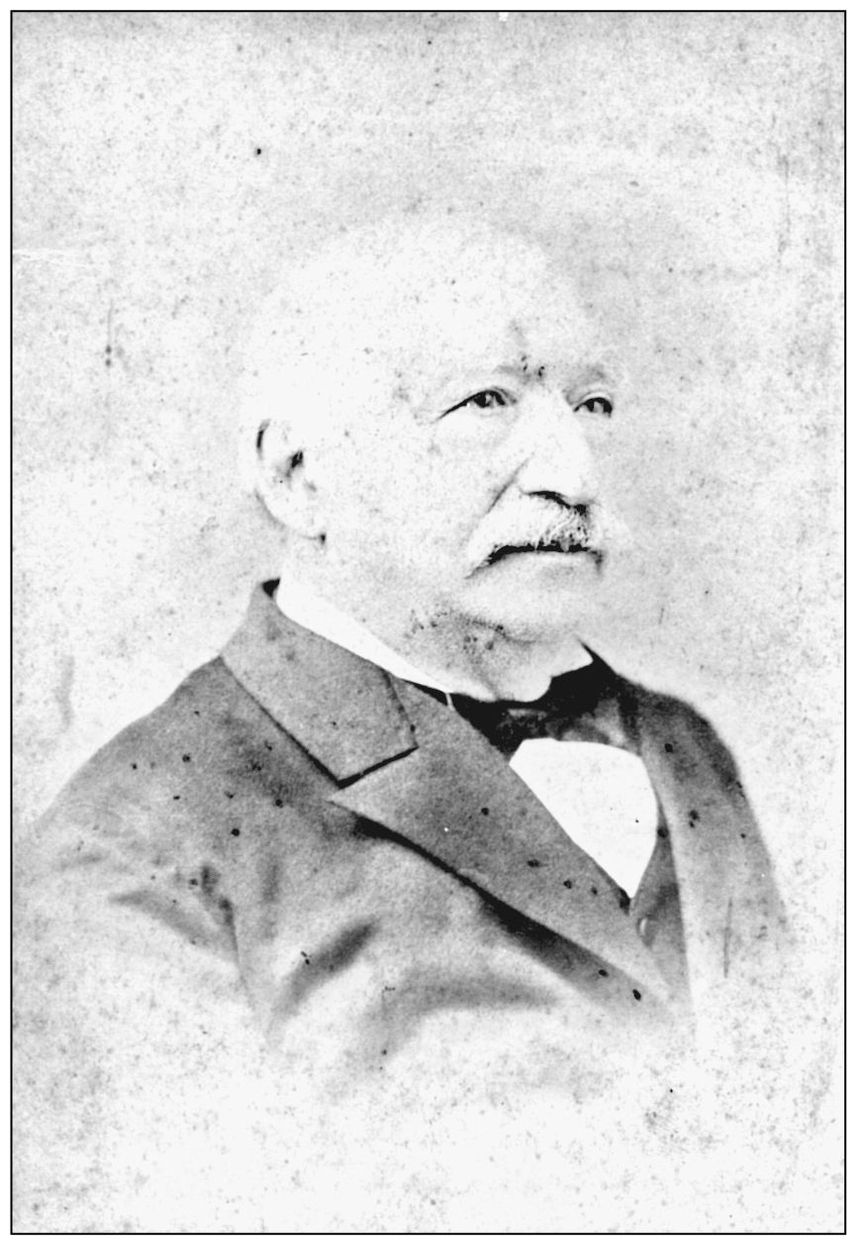

A native of Belfort, Alsace, Abel Dreyfous (1815–1891) left France about 1834, arriving first in New York City. There he heard about New Orleans, a city where French was spoken in the streets, and where the Civil Code, which was used in France, rather than Common Law, used in the rest of the United States, was the law of the land. For a lad who had studied to be a notary, New Orleans was the promised land. He survived first by making and selling soap, while clerking in the notarial firm of Cuvillier. After gaining his notarial commission, he became a partner with Cuvillier. The notarial acts of Abel Dreyfous form a significant body of work in the Notarial Archives of Louisiana. He was the most important Jewish notary of 19th-century New Orleans.

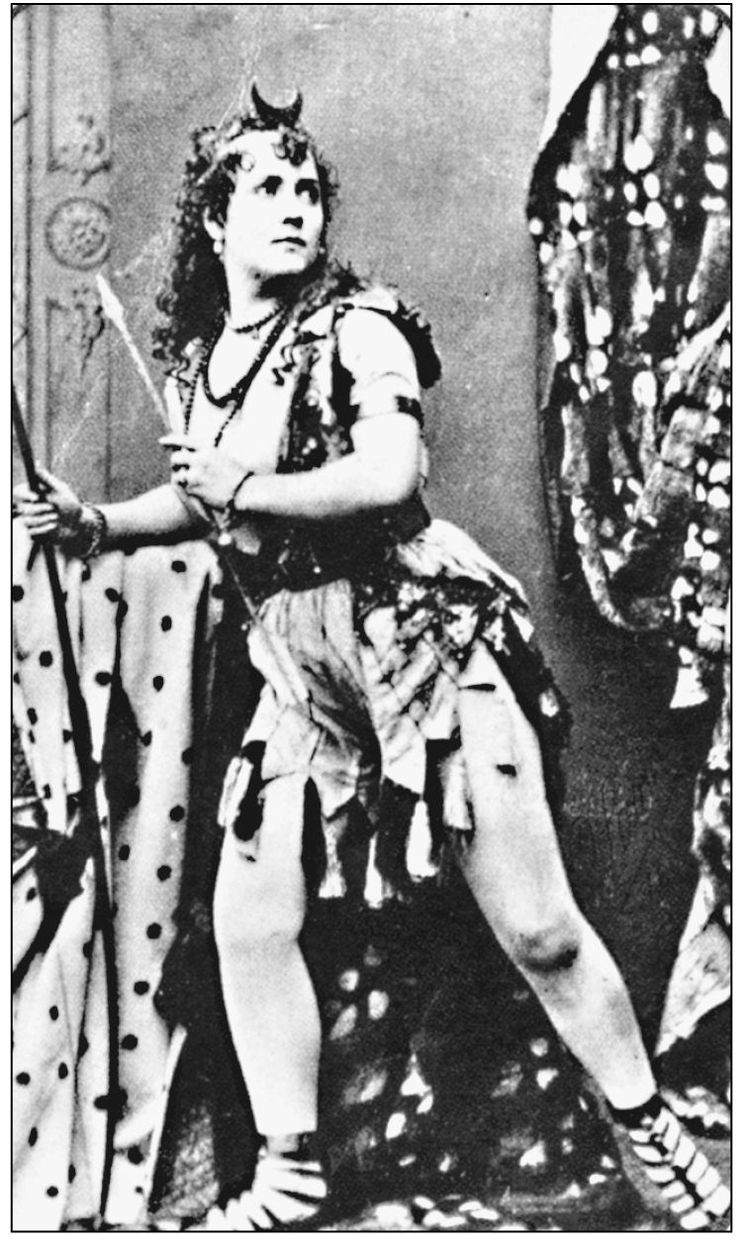

Adah Isaacs Menken (1835–1868) was born to a French Creole actress. As a child, she danced in the ballet at the French Opera House and wrote poetry. She took up the stage and married the Jewish orchestra leader Alexander Isaacs Menken. While not together long, she did adopt his Judaism and practiced it the rest of her life. As an actress, she was notorious for appearing in the play Mazeppa, in which she would ride off stage on horseback dressed only in skin-colored tights that made her appear nude.

Hermann Kohlmeyer (1814–1883), a brilliant Jewish scholar and linguist, was recommended by Rabbi Isaac Meyer Wise to serve on the proposed beth din that was to examine Wise’s prayer book, Minhag America. Occasionally he served as a temporary minister at both Gates of Mercy and Dispersed of Judah, but eventually he gave up the ministry for a career in education, becoming professor of Hebrew and Oriental literature at the University of Louisiana, now Tulane University. As Rabbi Max Heller later wrote, his “shrinking modesty and his retiring habits probably unfitted him for the responsibilities of the religious leader.”

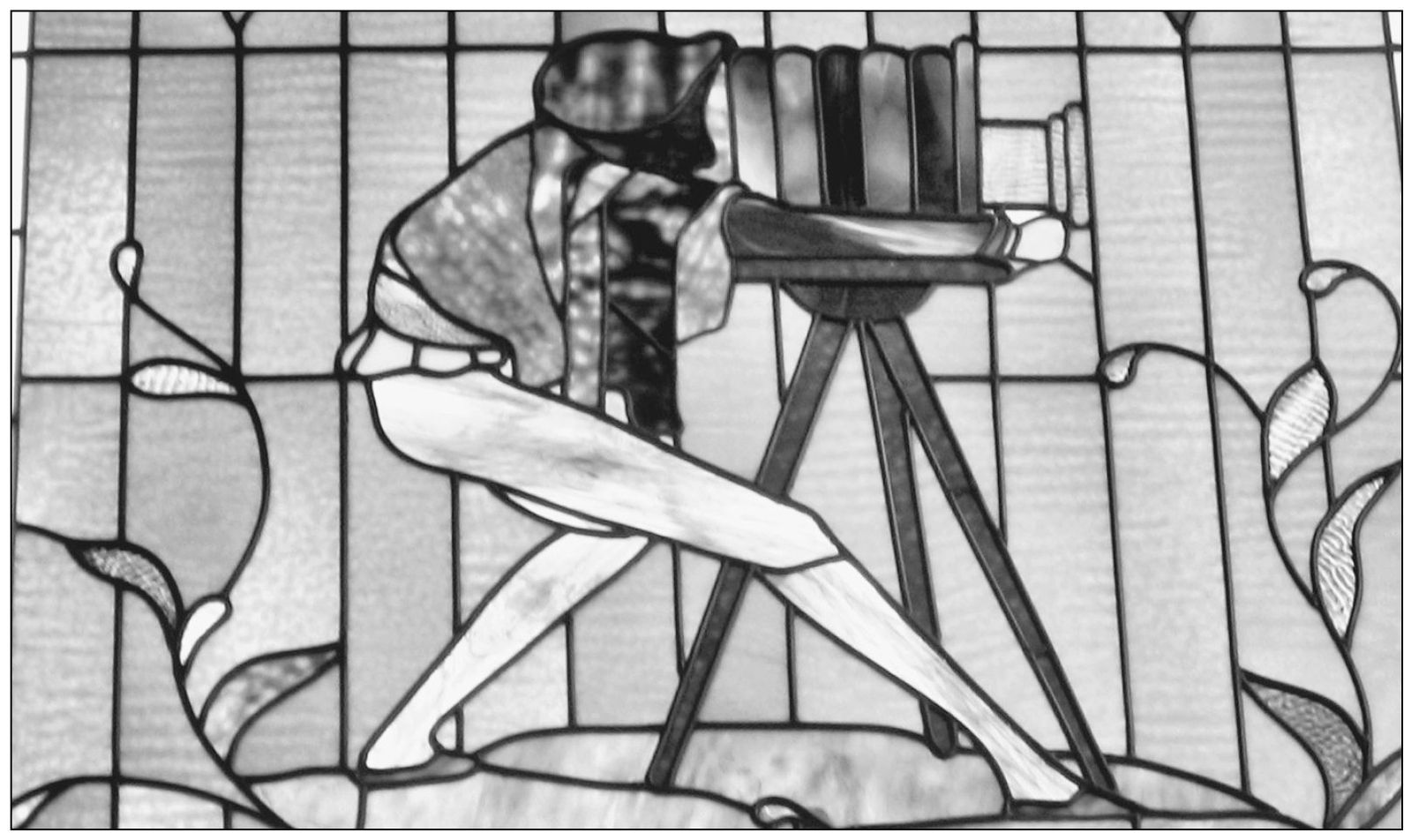

Samuel Moses (1798–1885) learned the art of camera obscura from Daguerre, its inventor, in Paris. When he came to New Orleans in the 1830s to work as a chemist in the sugar industry, he brought his photography equipment with him. He taught his sons Bernard (1832–1899) and Gustave (1836–1915) the techniques he had learned, which they employed professionally, first at Camp Street on the corner of Gravier, and later at Camp and Canal. At the end of the Civil War, Gustave photographed soldiers in their uniforms, at 25¢ a picture, as they were being mustered out. With the proceeds, he started G. Moses, later G. Moses and Sons, which was in business from 1866 to the 1930s. A stained-glass sign of a photographer with his head under a hood was displayed outside another studio location, now Preservation Hall, on Saint Peter Street.

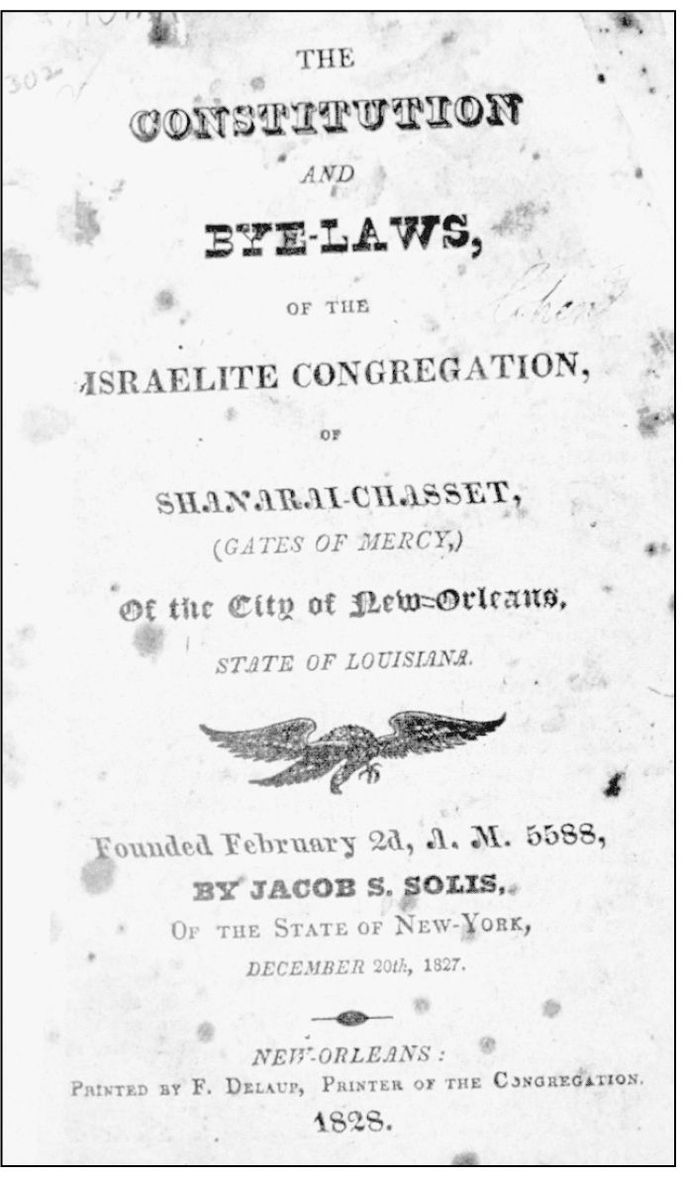

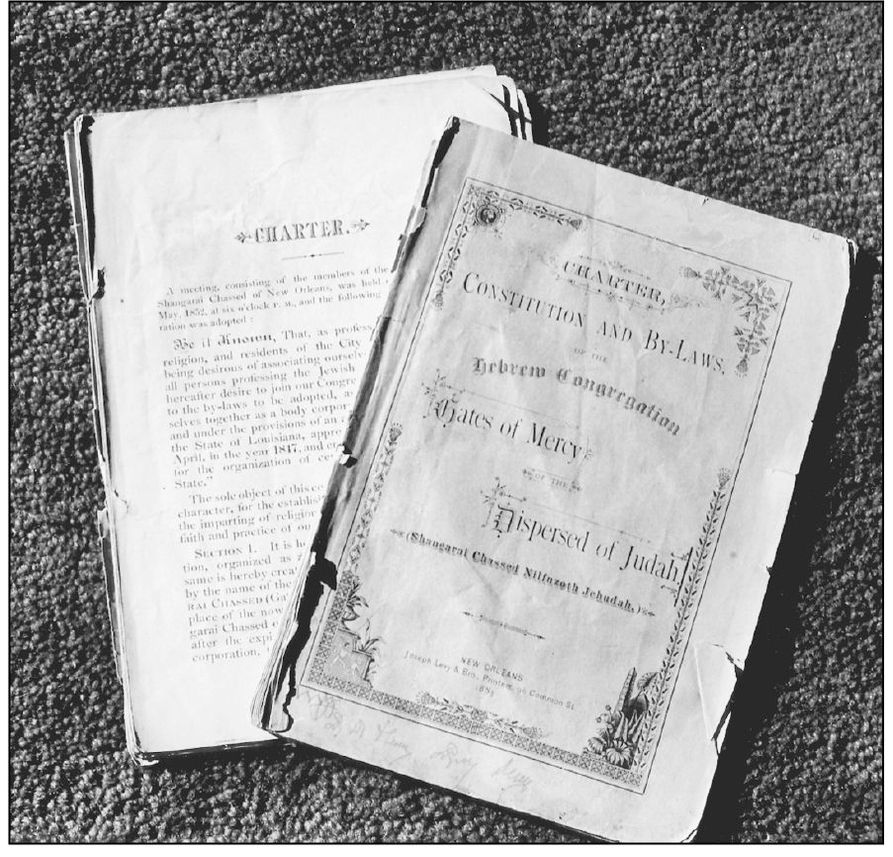

Shown here is the title page of the 1828 constitution of Congregation Shanarai Chasset, or Gates of Mercy. On the day before Passover in 1827, Jacob Solis, a New York merchant in New Orleans on business, went in search of matzoh to properly celebrate the holiday. Unable to find any for sale, he bought some meal and ground his own. Enraged by the lack of any Jewish communal life, he started a congregation. As only three of the 33 charter members of the new congregation were married to Jewish women, the constitution that Solis wrote made certain exceptions to the reality of New Orleans Judaism. It allowed that these “strange”—that is, Gentile—spouses could be buried in the congregational cemetery. Also contrary to Jewish law, the constitution allowed the children of these Gentile spouses to be considered members of the congregation and, therefore, Jewish. Solis left New Orleans for home after six months, promising to return with a Torah and prayer books, but he died in New York before his return, leaving the congregation without knowledgeable religious leadership.

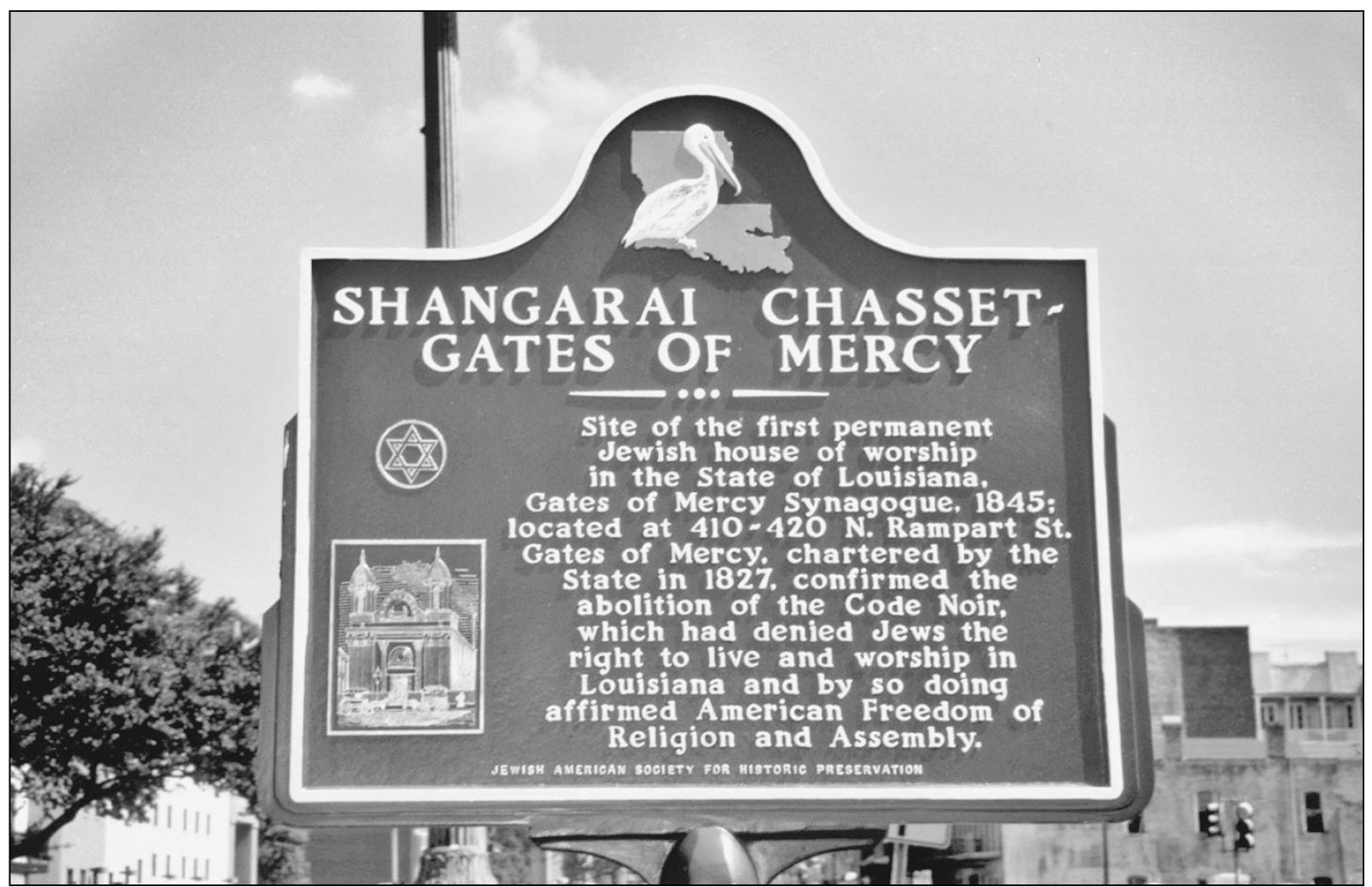

This plaque commemorates the first congregation in Louisiana, Gates of Mercy. The building the congregation moved into in 1843, which was to be their synagogue, was the first building owned by a Jewish congregation. It was in terrible disrepair, so donations were solicited, the building torn down, and a new one dedicated in 1851.

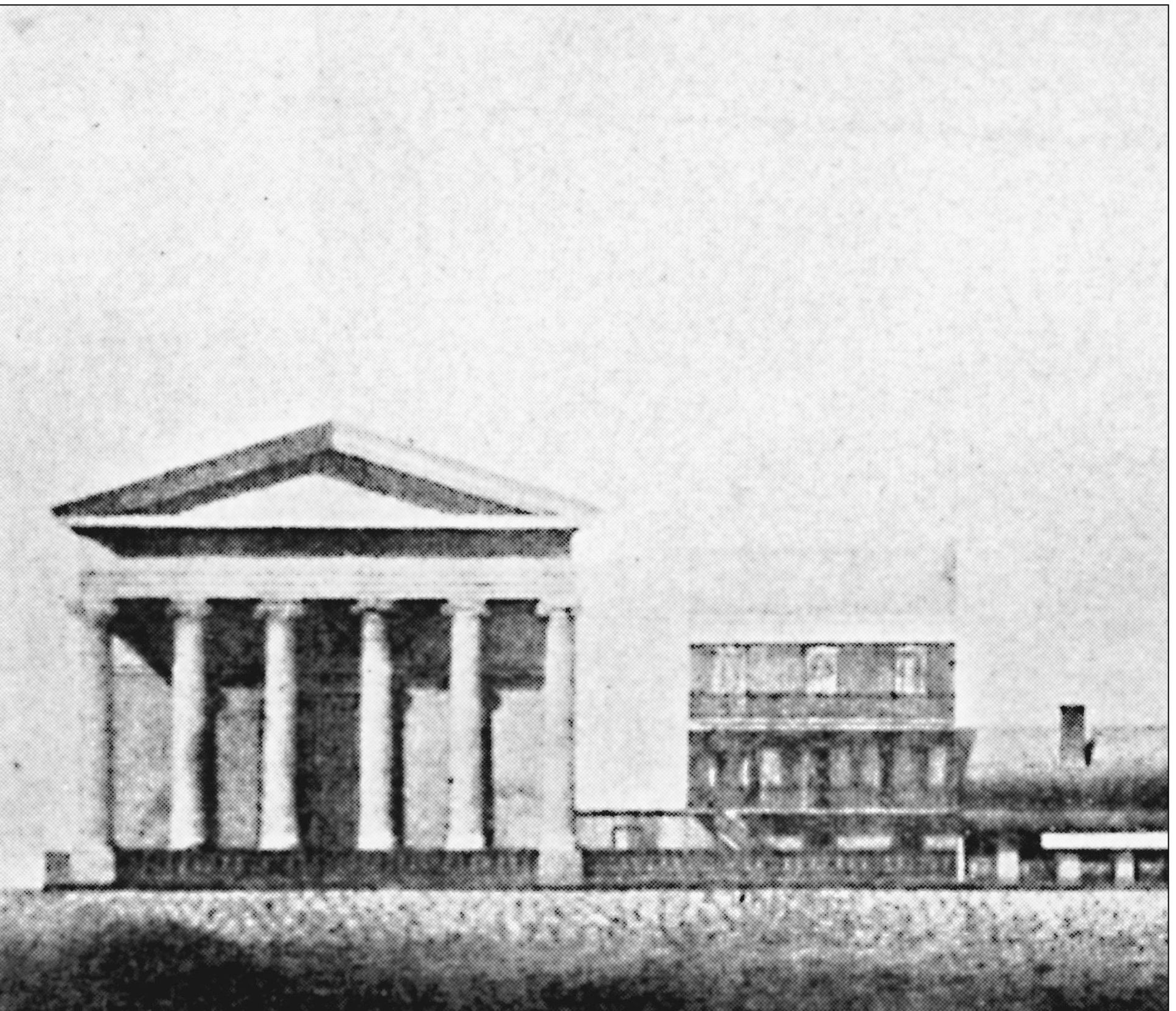

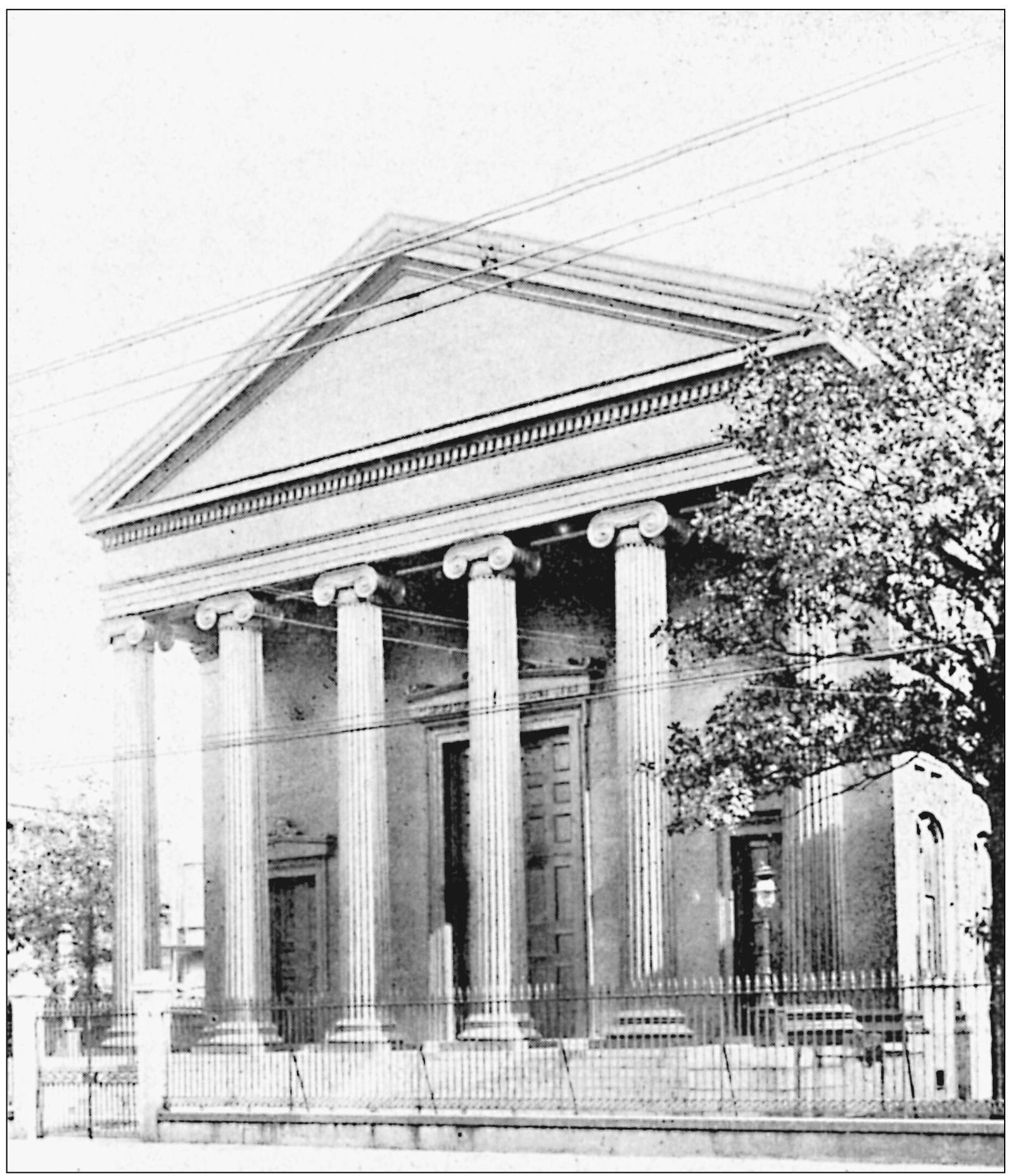

The first building dedicated as a synagogue was on the corner of Canal and Bourbon Streets. Nefutzoh Yehudah, or Dispersed of Judah, founded in 1845, was named by Gershom Kursheedt to honor Judah Touro in hope of inspiring Touro’s largesse. Kursheedt’s plan worked, for two years later Touro gave the Sephardic congregation this property that he owned, Christ Church. The building was small and the church members wanted to build a larger edifice. Touro, who owned a pew in Christ Church, swapped this property with a vacant lot he owned two blocks down Canal

Street and then gave this building to the new Jewish congregation to become their sanctuary. Renovations took three years, mostly due to Touro’s interference, but the synagogue was finally dedicated May 14, 1850. There were two dedications: one in the morning for just a few invited guests, bowing to the wishes of the reclusive Touro, and a grand dedication that afternoon with the entire city invited to the festivities.

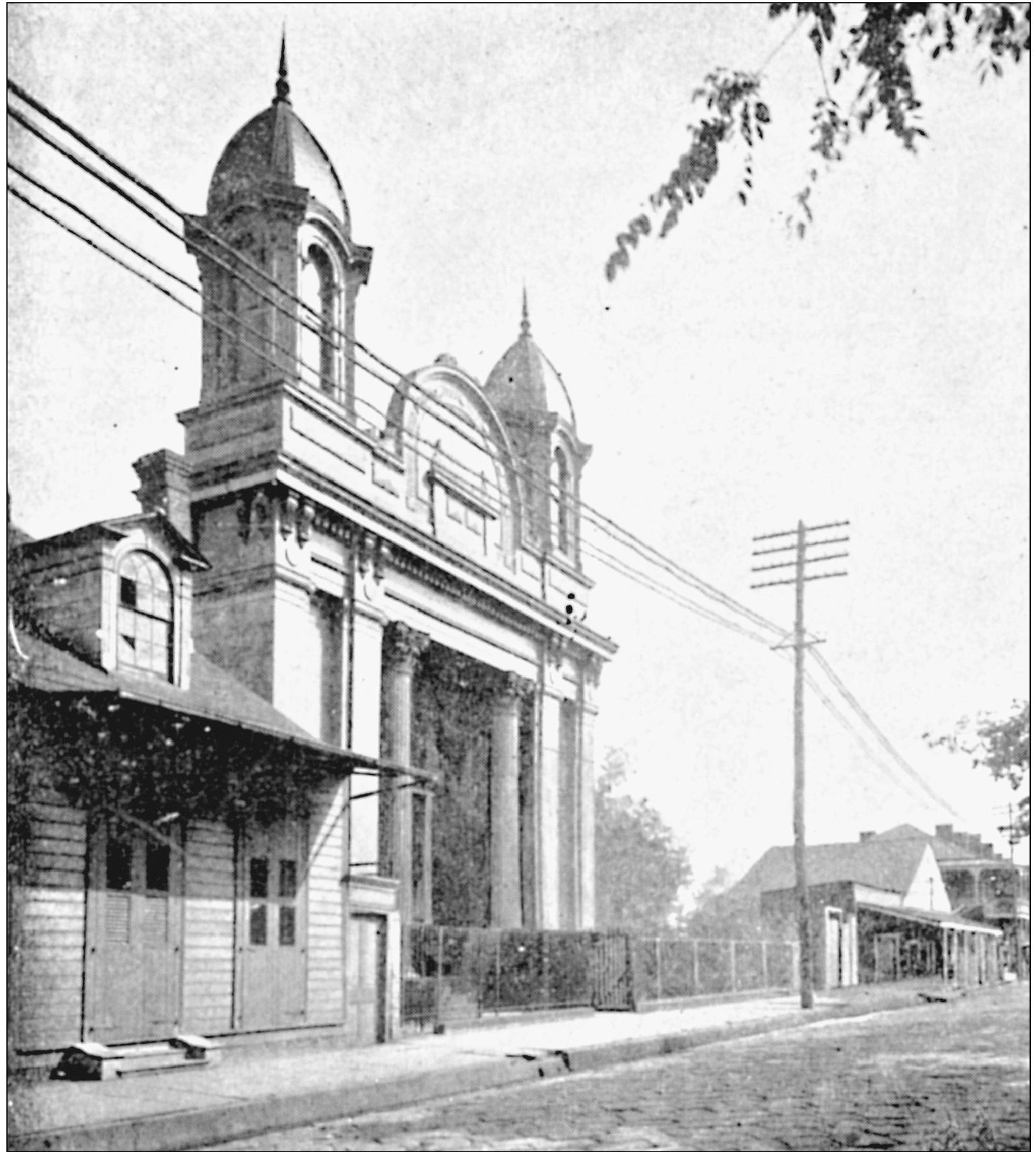

Founded in 1827, Gates of Mercy moved into an existing building in the 500 block of North Rampart in 1843. The building was in some disrepair, and a donations drive for a building began. The drive floundered, influencing Gershom Kursheedt to begin a drive for a Sephardic congregation. With Congregation Dispersed of Judah refurbishing their new synagogue, the members of Gates of Mercy once again sought to rebuild, and thanks in large part to a sizable donation from Judah Touro, the new Gates of Mercy was dedicated in June of 1851.

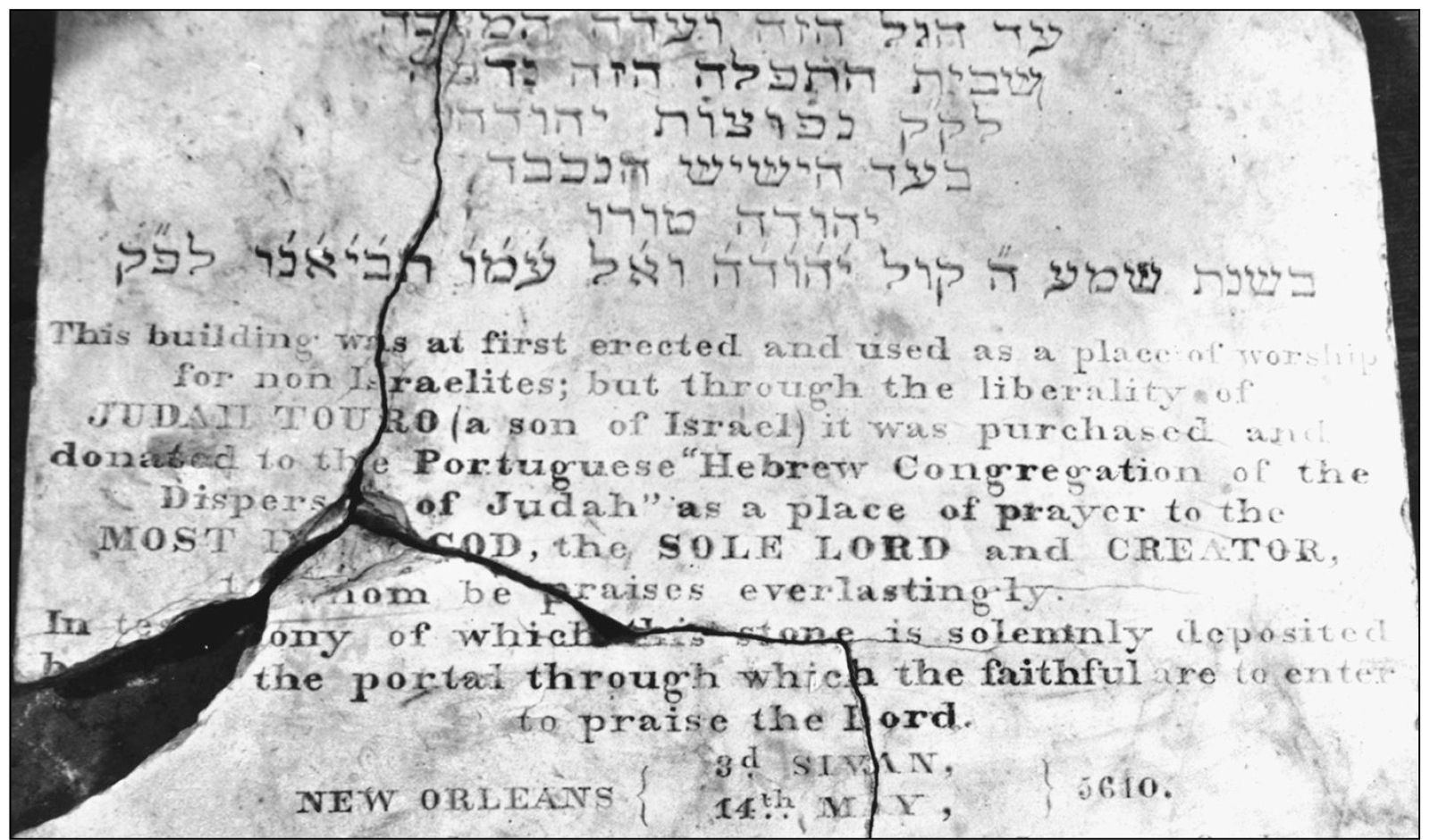

Congregation Dispersed of Judah was dedicated in 1850. The former Christ Church building on Canal Street had been renovated, with funds from Judah Touro, to become a synagogue using the Portuguese service. Along with other changes, a stone plaque was sealed into the portal. It commemorated the generosity of Judah Touro, and says, in Hebrew, the following: “This building was first erected and used as a place of worship for non Israelites; but through the liberality of Judah Touro (a son of Israel) it was purchased and donated to the ‘Hebrew Congregation of the Dispersed of Judah’ as a place of prayer to the Most Holy God, the sole Lord and Creator to whom be praises everlastingly. In testimony of which this stone is solemnly deposited beneath the portal through which the faithful are to enter to praise the Lord.”

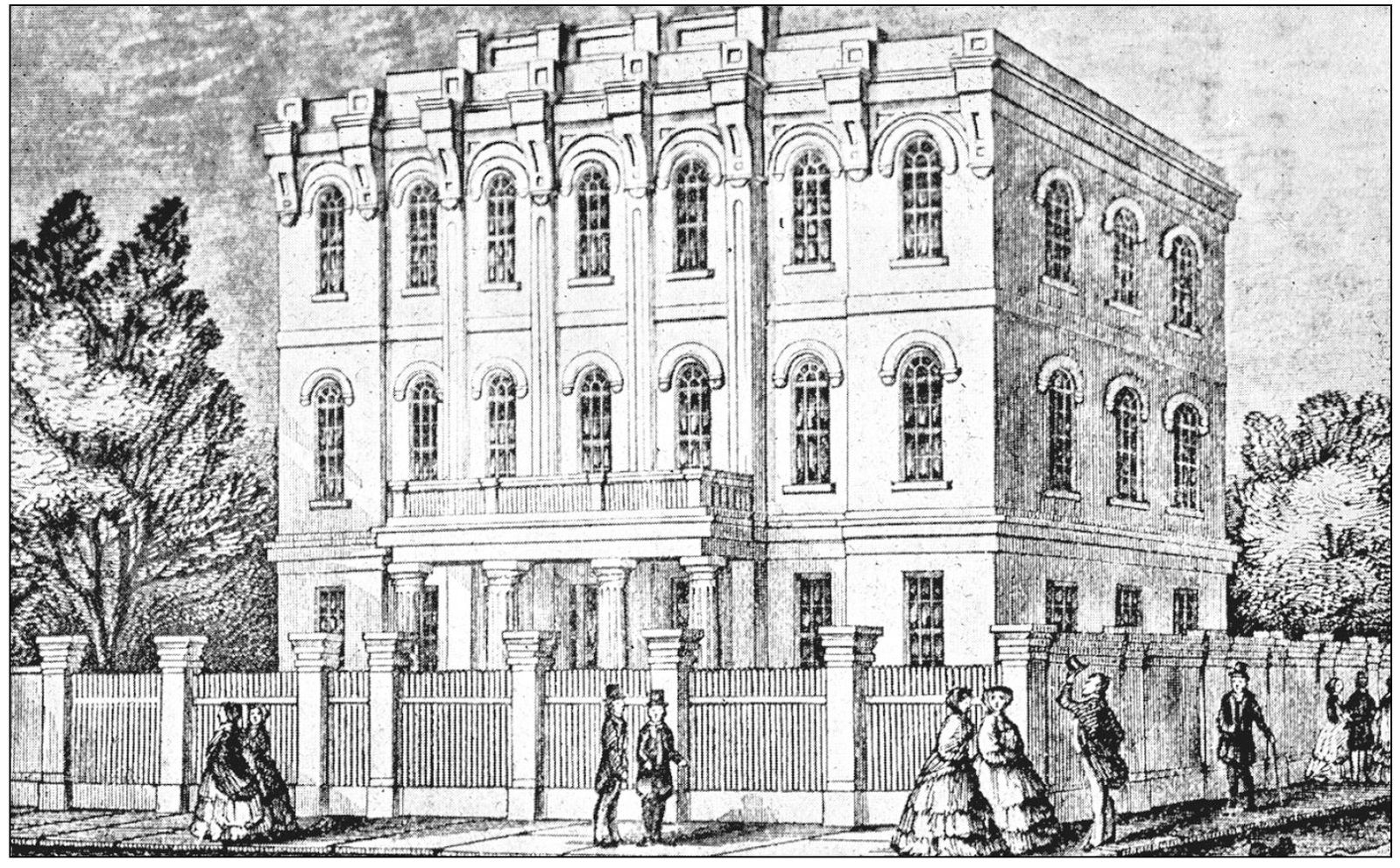

Congregation Shaare Tefilah, or Gates of Prayer, was chartered in 1850 in the “uptown” suburb of Lafayette City, three miles upriver from the city proper. Like Gates of Mercy, the members were primarily Alsatian and German. The first synagogue was a small, wood structure bought in 1855, located at the corner of St. Mary and Fulton Streets.

In his famous will, Touro left Congregation Dispersed of Judah the property the synagogue sat on and the large property he owned adjacent, the rents to be used for a Hebrew school and to pay the minister. The building on Canal Street was small, so the congregation decided instead to use the money to build a new synagogue further uptown. The building was completed in 1857. It so resembled the original that many people thought the first building had been moved to the new location.

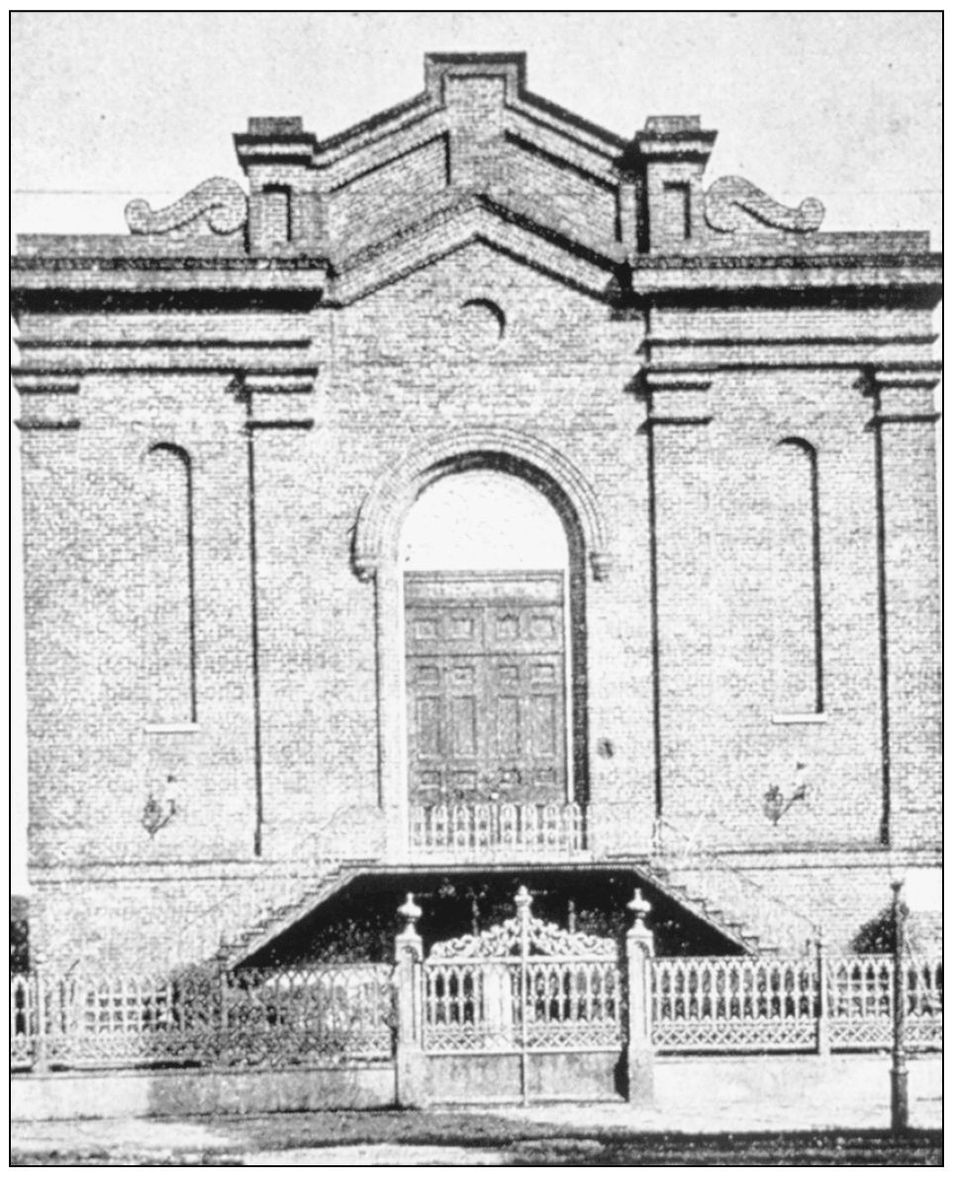

Because of economic and social differences, the members of Gates of Mercy ignored entreaties from Gates of Prayer for some sort of an amalgamation between the two congregations. In 1859, a brick collection campaign was begun in preparation for building a new synagogue, but due to the Civil War, the sanctuary was not dedicated until 1867.

Due to the ravages of yellow fever and other deadly diseases, many women were left widows and many children left orphans. To help those that had lost loved ones, members of the Hebrew Benevolent Association opened the Widows and Orphans Home, only the second such home in the United States. The first site of the Widows and Orphans Home, on Jackson Avenue and Chippewa Street, opened in 1856.

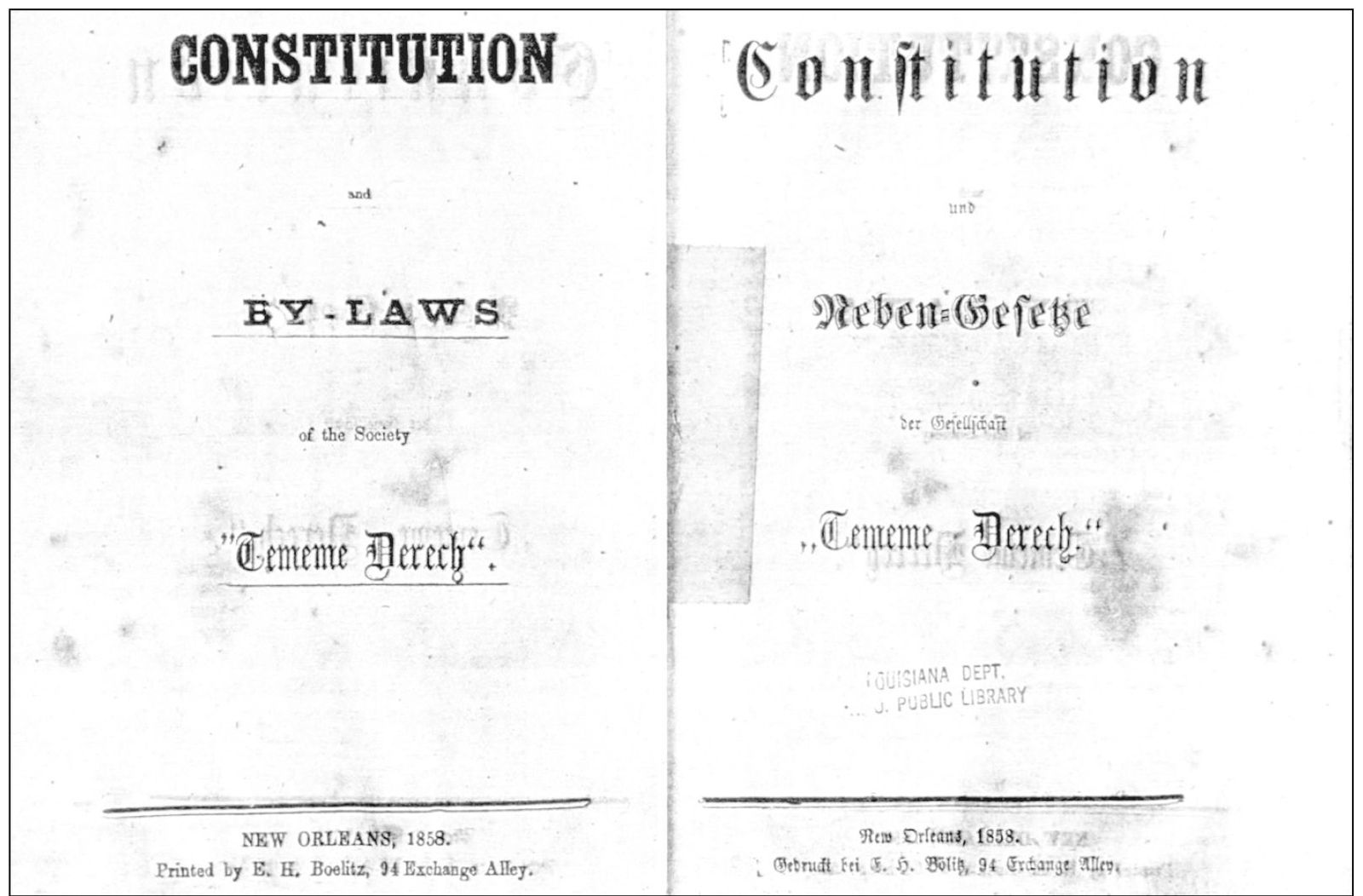

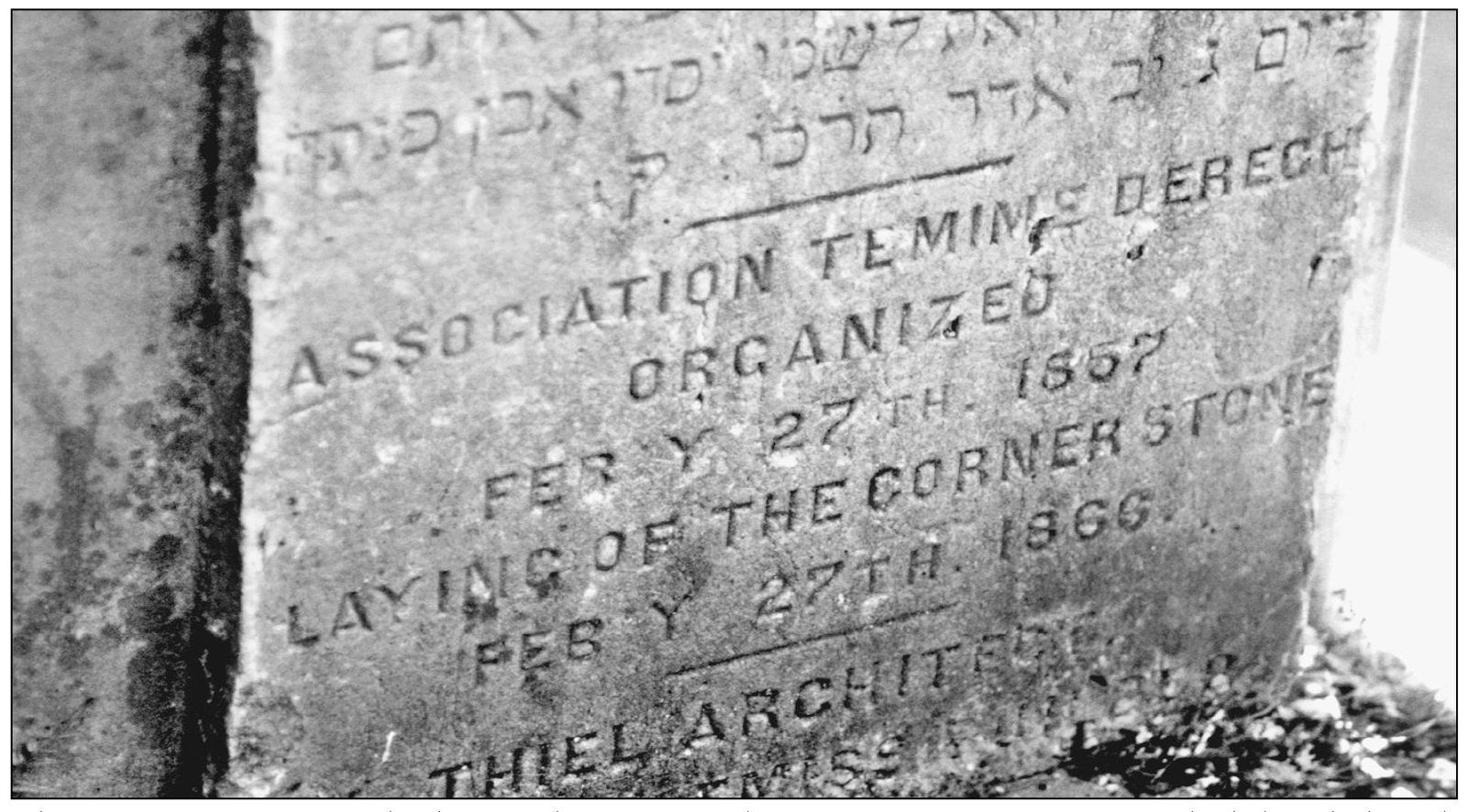

Shown here are the Tememe Derech constitution and by-laws. Chartered in 1857 by Prussians, primarily from Posen, which for most of its history had been part of the Polish Empire, the members practiced the Polish minhag, or ritual. This was the only one of the small Eastern European congregations to build its own synagogue, dedicating the building in the 500 block of Carondelet Street in 1867.

The congregation never had more than 50 members. In 1904, Tememe Derech disbanded, and, together with many of the other small Orthodox congregations, they merged together to form Congregation Beth Israel. This cornerstone now sits in the corner of Beth Israel’s “Little Shul,” at the congregation’s original location on Carondelet Street, even though the congregation moved near the Lakefront in 1970.

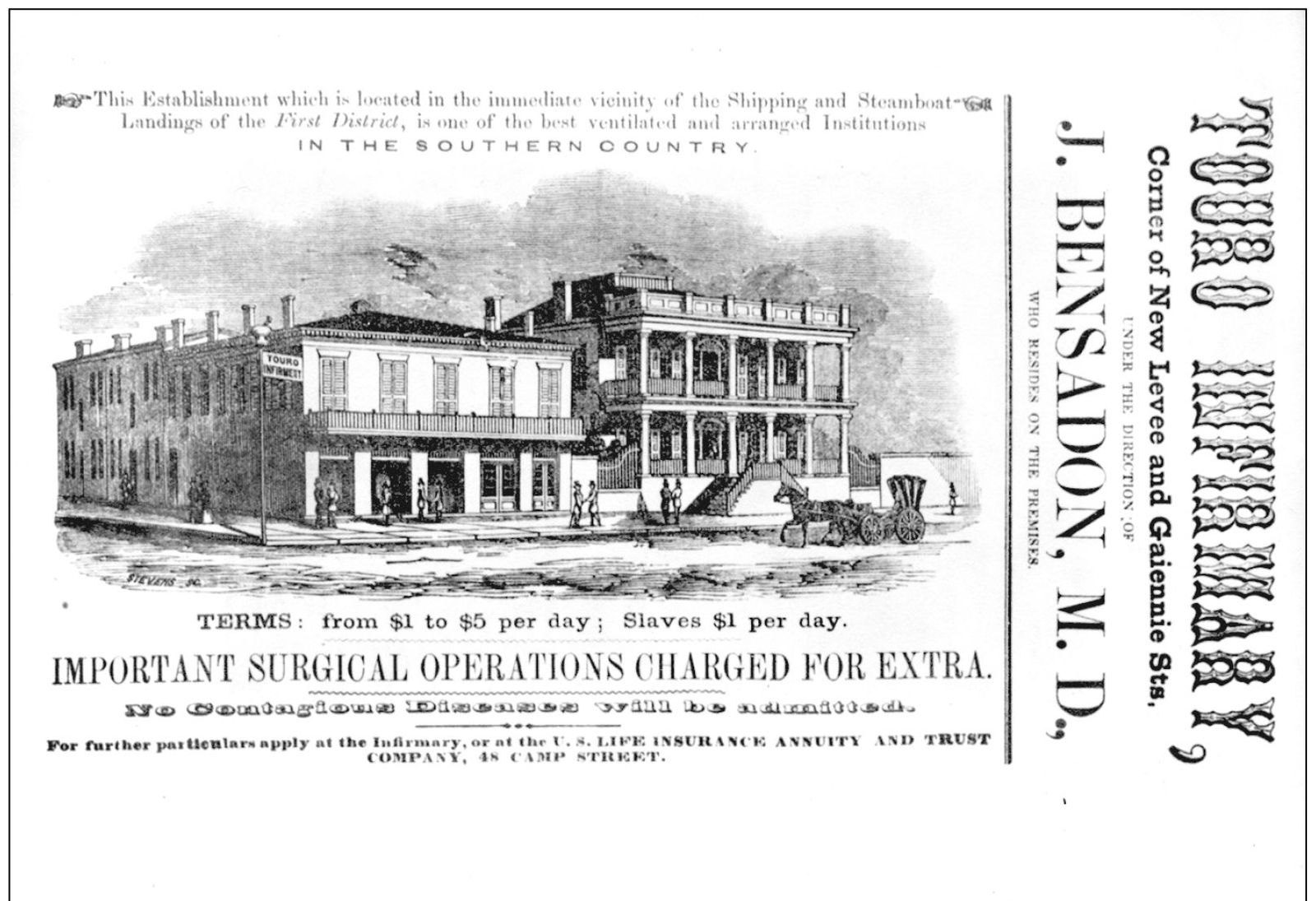

Judah Touro founded Touro Infirmary in 1852 (above) as a small waterfront hospital in a plantation house he purchased at auction from the Paulding estate. It housed 28 patients, with Dr. Joseph Bensadon as house physician. Its first patients were seamen from international ships, slaves, and immigrants often paid for by the Hebrew Benevolent Association of New Orleans. Upon Touro’s death in 1854, he willed the “Hebrew Hospital” the property, with the mandate “as a charitable institution for the relief of the indigent sick.” He named his executors as directors of the institution. In 1874, the Hebrew Benevolent Association merged with Touro Infirmary to provide financial support for the hospital. Following the yellow-fever epidemic of 1878, Touro Infirmary moved uptown in 1882 (below) to Prytania Street and built a large hospital that served much more of the community.

Joseph Bensadon (1819–1871) grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, receiving his medical doctor degree from the Medical Society of South Carolina in 1838. He enlisted in the army in the Mexican War, after which he settled in New Orleans. He had the good fortune to gain the respect and patronage of philanthropist Judah Touro, who purchased a waterfront building at auction to serve as a hospital for seamen initially, but which grew to serve the entire community. Dr. Bensadon was house physician (and almost the entire medical staff) from 1852 until he enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1861. After the end of the war, he returned to New Orleans, where he engaged in private practice until his death.

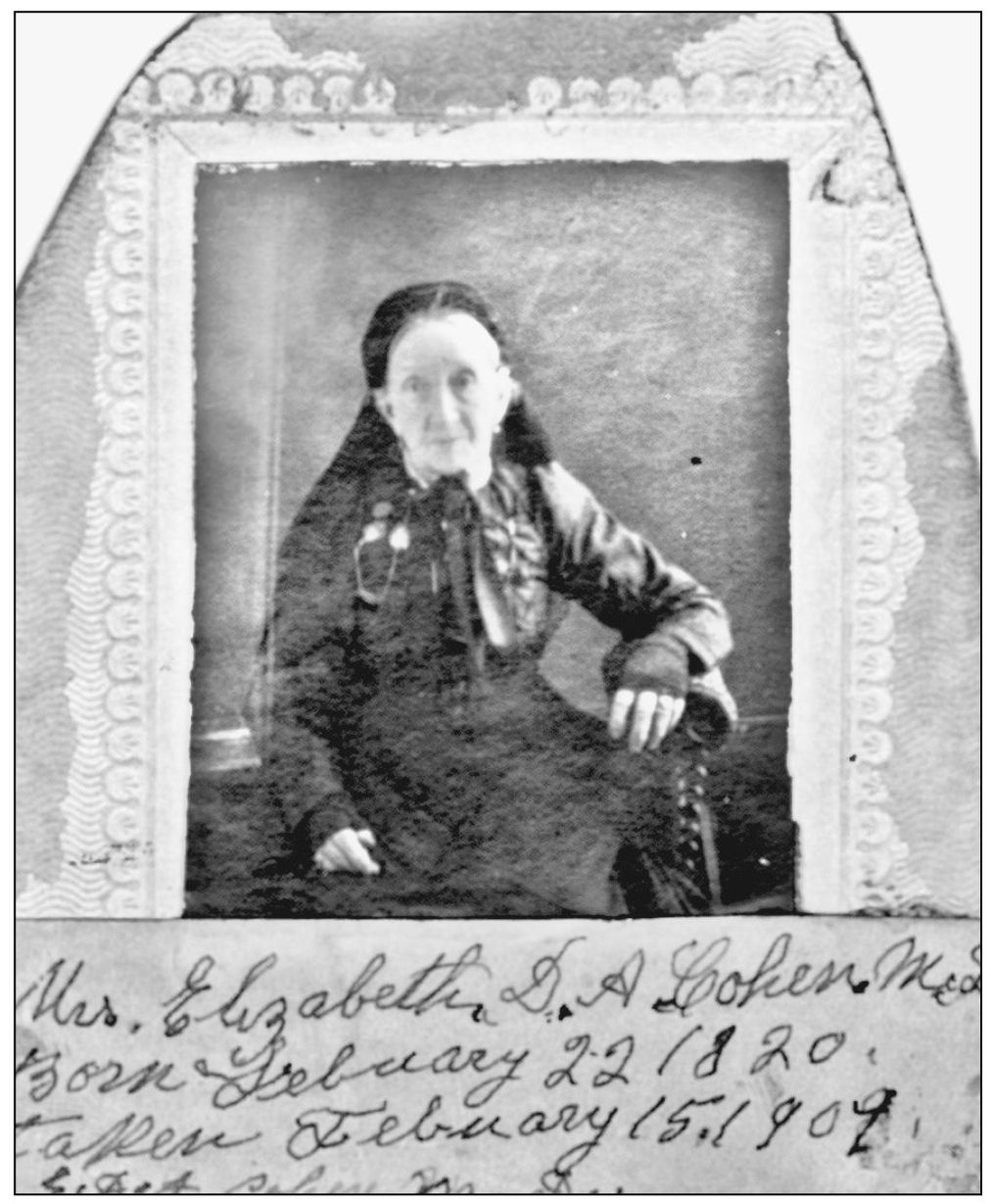

Elizabeth D. A. Cohen (1820–1921) was the first woman physician in Louisiana. After her marriage to Dr. Aaron Cohen, and the birth of her five children, she enrolled in the Philadelphia College of Medicine, the first women’s medical school in the United States. She joined her husband in New Orleans in 1857, and worked side by side with male doctors through yellow fever and other epidemics. She specialized in family practice, mostly treating women and children. In her long life, she said that she had delivered babies of young women she had brought into the world. After her retirement, she entered the Julius Weis Home for the Aged on the Touro Infirmary campus, where she worked as a hospital volunteer. She lived to be 101.

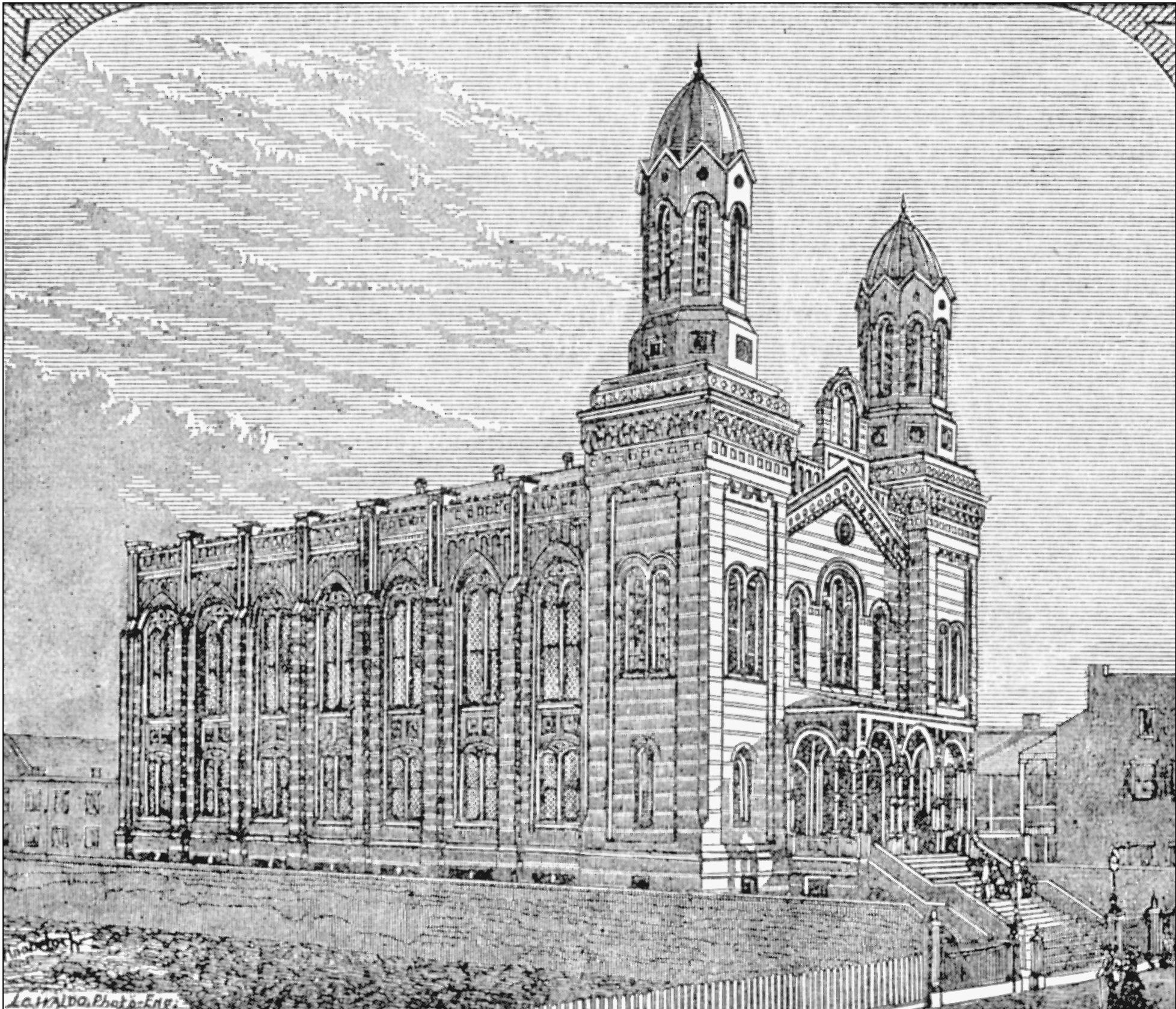

Temple Sinai, the first congregation in the city founded on Reform principles, was chartered in 1870 as a Reform congregation primarily by members of Gates of Mercy who felt that the movement toward Reform at that congregation was stagnating and who wanted a new sanctuary built closer to where the members lived. They also wanted their “temple” to represent the pride and confidence the members felt in proclaiming their Judaism as well as their economic success. The temple was dedicated two years later and was a landmark for years, long after the congregation moved even further uptown in 1928.

Following the new Reform traditions, Temple Sinai was built with an organ and soon organized a choir, replacing the traditional cantor. This picture of the volunteer choir in about 1890 shows the enthusiasm with which this “Americanization” of the service was greeted. The only person the authors can identify is the white-mustached old gentleman in the back row. He is Leon Cahn, who organized the choir and sometime substituted for clergy. In 1990, Temple Sinai membership voted to engage the services of a cantor, while retaining both choir and organ music.

In the early 1860s, the Deutsche Company was founded “to foster sociability . . . and fellowship” at 112 Common Street. They put on plays and other entertainment. Another group, calling themselves “The Harmony Club” and organized for social purposes, were located on Camp near Julia Street. In 1872, the “Company” consolidated with its younger counterpart and became The Harmony Club at the corner of Exchange Alley and Bienville Street. They were chartered in 1880 for the purpose of “the cultivation of sociability, and the fostering of intellectual culture, . . . and the advancement of the members in science and literature.” Among its various locations in the next few years was the beautiful and elaborate building on Canal Street, now occupied by the Boston Club. Their final home, which is pictured here, was on Saint Charles Avenue at the corner of Jackson Avenue.

In 1881, the two oldest congregations, Gates of Mercy and Dispersed of Judah, decided to consolidate. Many members of the German congregation had left to join Temple Sinai, and those remaining were decimated by the yellow-fever epidemic in 1878. Dispersed of Judah lost members when many married out of the faith. According to the consolidated charter, members of Dispersed of Judah were granted membership into Gates of Mercy and the conjoined congregation prayed in the Dispersed of Judah synagogue on Carondelet Street.

Some of the oldest Jewish headstones in the city are found at the Gates of Prayer Cemetery on Joseph Street. This plot of land was purchased soon after the founding of the congregation in 1850. These early headstones have been saved and placed in line. Most of the early members of the congregation were Alsatians, and many of these early headstones were written in French.

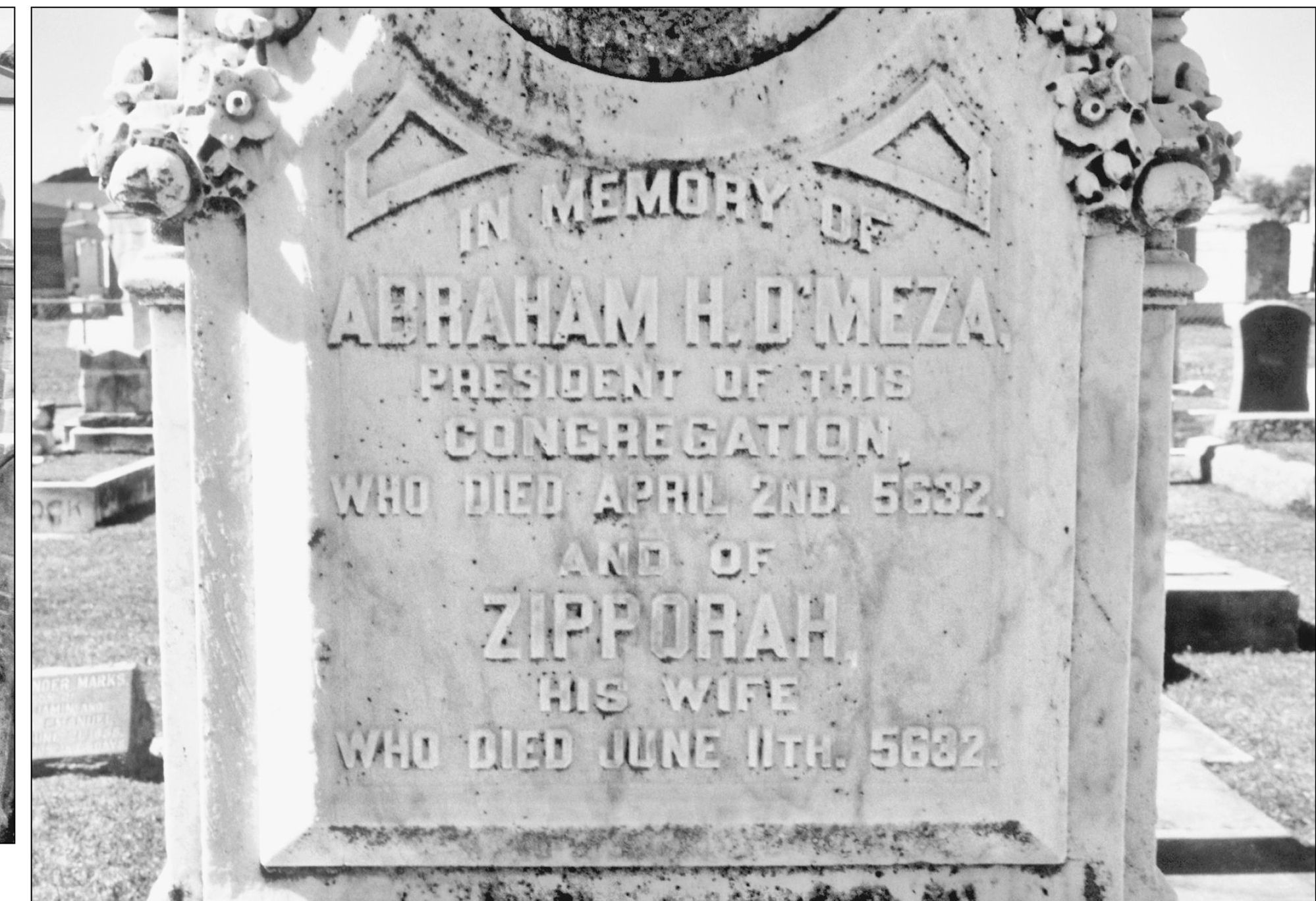

Picture here are the headstones of Abraham D’Meza, the longtime president of Congregation Dispersed of Judah, and his wife, Zipporah. D’Meza was born in Curacao, just as many of the members of Dispersed of Judah were from the Caribbean and of a Spanish or Portuguese Sephardic background. The year of death is the Hebrew year 5632, which was 1872. The stone was “erected as a token of respect by the congregation” for his years of service.

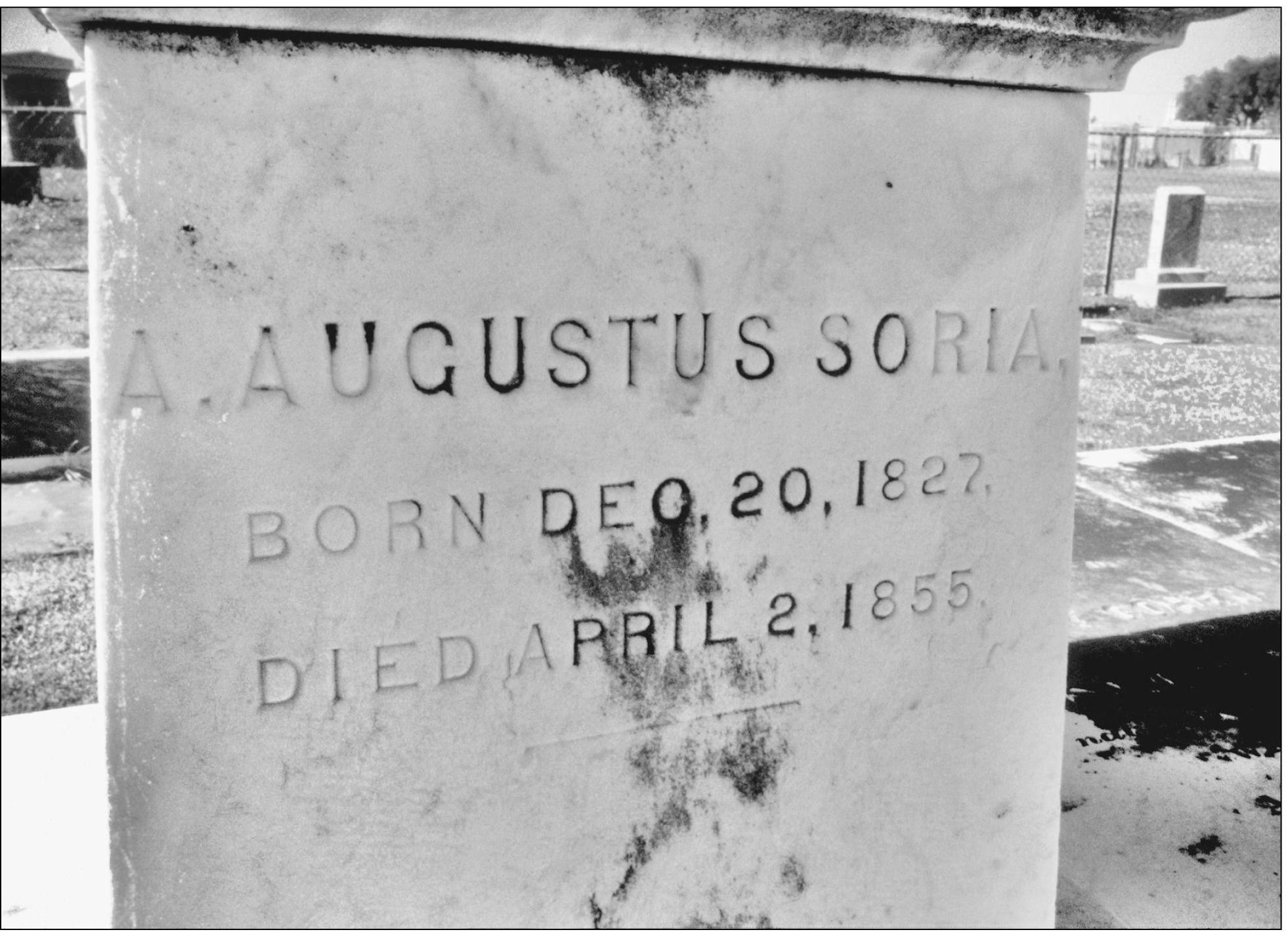

Here is the headstone of A. Augustus Soria. He was one of the earliest burials in the Dispersed of Judah Cemetery. Upon his death in January 1854, Judah Touro was temporarily interred here. In the spring of that year, his body was removed to the Touro family plot in Newport, Rhode Island.