Chapter 1

Genres and Subjects

Introduction

This chapter introduces you to two important categories in the description of art-historical works that comprise the theme: subjects and genres. It explains the distinctions between and sub-categories within the terms, and the innumerable ways in which artists have interpreted them. This chapter covers the most ground in the book, and many of its examples can be used as a basis for study under the other five chapter headings.

Genre means ‘type’ or ‘category’. Examples include ‘still life’, ‘landscape’, ‘portrait’ and ‘history painting’. However, genre can also refer to a specific type of painting known as ‘genre’, which depicts scenes from everyday life. There was a system for ranking art in terms of its cultural value known as the ‘hierarchy of genres’. The most well-known formulation was provided in 1667 by André Félibien (1619–1695), a historiographer, architect and honorary consultant to the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The history of art tended to follow this ranking until the twentieth century, and knowledge of the hierarchy of genres is very important for the understanding of Western painting, as it provides insight into the scale and treatment of many works.

The subject of a work might be something like ‘fruit’, ‘mountains’, ‘family group’ or ‘war’ and this might help to define the work’s genre. Some works fall into two or more genres, or between subjects and genres. This chapter will provide you with the knowledge and understanding to make these judgements, and the multiple placements of works will be made clear within the text.

In addition, this chapter will enable you to compare and contrast works of art of a common genre, noting points of similarity and difference in relation to both formal and interpretational aspects of the works chosen. Formal aspects might include: composition, scale, use of colour and tone, depiction of light and space, technique and materials and degrees of finish and detail. Interpretational aspects might include: aesthetics (the branch of philosophy which relates to beauty and taste), ideology (a particular set of ideas or values related to certain social groups) or iconography (formal and symbolic elements in relation to their wider social and historical context). The social and historical context of visual representation is examined explicitly in Chapter 4.

History Genre

History painting as a form of narrative or istoria (historical, biblical or mythological narrative) has been specified as the highest of achievements as far back as the Renaissance. Acts of human virtue and intellect by moral heroes, including those in Christian stories (the dominant religion in Europe), were placed at the top of what would become the hierarchy of genres. History paintings were usually large-scale works depicting a subject based on classical history, literature or mythology from ancient Greece and Rome, a scene from the Bible, or real historical events.1

History paintings were ideally suited to public spaces and large canvases. The scenes depicted were usually heroic or noble, the aim of these works being to elevate viewers’ morals. It was important that they provided the opportunity to depict the human figure – often nude or partially nude – since this subject was believed to require the greatest artistic skill. From the fifteenth until the nineteenth century, these enactments of human virtue were placed at the top of what would become the hierarchy of genres, and as a result many artists aspired to be history painters.

Why were paintings ranked? The ‘hierarchy of genres’ was adopted because it embodied Renaissance values about what constituted the ‘best’ types of art. By the mid-seventeenth century the codification of genres had been firmly established by André Félibien.2

In his Preface to Conférence de l’Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (1669), Félibien stated: Thus, the artist who does perfect landscapes is superior to another who paints only fruit, flowers or shells. The artist who paints living animals deserves more respect than those who represent only still, lifeless subjects. And as the human figure is God’s most perfect work on earth, it is certainly the case that the artist who imitates God by painting human figures is more outstanding by far than all the others. (Quoted in Edwards, Art and Its Histories: A Reader, p. 35)

‘History’ painting was considered to be the grande genre because, unlike the lower-ranked genres, it provided the artist with the opportunity to demonstrate (and the viewer to experience) moral force and imagination. However, genres are not exclusive and one work may include elements of more than one genre.

Ancient Classical history and mythology

After winning the Prix de Rome, French painter Jacques-Louis David (1748– 1825) saw the works of Antiquity first hand, and developed a Neo-classical style favoured by the French Academy, the institution that controlled the production and exhibition of art in France. The Oath of the Horatii, 1784, is a large-scale work from the artist’s imagination, inspired by stories of ancient Rome and the wars between Rome and Alba around 669 bce, as described by Livy (59 bce–17 ce) in his monumental History of Rome.3

Writing during the reign of Emperor Augustus, Livy is likely to have embellished Rome’s history in a way that helped establish the empire’s validity.

Figure 1.1 | Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 330 × 425 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Source: akg-images / Erich Lessing.

The three Horatii brothers are preparing to do battle with three brothers from the Curiatii family in Alba to settle the dispute between their cities. The scene depicts them swearing on their swords, held aloft by their father, to defend the city of Rome to the death. Rejecting the contemporary Rococo style on account of its lyrical form, looser brushwork, all-round gaiety, and lack of seriousness and moral rectitude, David organises the canvas with geometric precision. The linear perspective, made explicit by the chequerboard floor, helps to heighten our sense of austerity and rationalism. Compositionally, the arches with Doric columns frame the three sets of figures, underlining the significance of the number three in the story. The muscularity of the men is heightened by the angle at which the light (which enters from upper left) rakes across the surface of their bodies, sharply delineating mass and volume.

The entire canvas demonstrates Roman patriotism. David’s precise delineation and modelling is a kind of homage to antique sculpture, and helped ensure that this monumental and moralising work perpetuated and maintained the political ideology of revolution on the eve of the French Revolution (1789–1799). While the painting does not depict a real historical event, the Oath of the Horatii presents a form of narrative or istoria in its enactment of stoic bravery. The painting is also examined in Chapter 6, in relation to the theme of ‘gender’.

Figure 1.2 | Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520–1523, oil on canvas, 176.5 × 191 cm, London, National Gallery.

Source: © 2015. Copyright The National Gallery, London / Scala, Florence.

Large-scale mythological scenes, especially multi-figured ones, were also categorised under the history genre. For example, the mythological painting The Rape of Europa, 1559–1562, by Italian painter Titian (originally Tiziano Vecelli/o, 1488/90–1576), demonstrates the way in which some history paintings used classical iconography and antique literary sources as inspiration. Europa’s rape by Zeus is one of many mythological themes taken from the Roman poet Ovid’s narrative poem Metamorphoses, a text that had become widely read among the educated classes during the period. Ovidian myth is also the inspiration for Titian’s painting Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520–1523.

In the painting, Bacchus, god of wine, is leaping into the air from his chariot upon sight of princess Ariadne, with whom he has fallen in love. Ariadne had been abandoned on the Greek island of Naxos by her lover, Theseus, whose ship is shown in the distance. Bacchus offers Ariadne the sky in return for becoming his immortal wife. His promise to transform her into a constellation is signalled by the stars above her head. Think about the way Titian has used the formal device of composition to enhance his story telling.

Biblical scenes: narrative in fresco

As well as subjects from classical history and mythology, the history genre also included revered religious istoria epitomised by the work of the Early Renaissance Italian painter Masaccio (originally Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, 1401–1428/29). His biblical fresco painting The Tribute Money, 1425–1428, depicts a scene from the Gospel of St. Matthew. It is part of Masaccio’s famous fresco cycle depicting the life of St. Peter commissioned by the Brancacci family for their chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

Not all biblical works need to tell a story; however, this continuous narrative tells the story of St. Peter being asked to pay tax. Grey-haired St. Peter appears three times in this monumental scene: first, positioned in the central group among the apostles, during Christ’s instruction to find a coin from the mouth of a fish; second, kneeling down at the water’s edge to retrieve a coin from the mouth of a fish; third, handing over the coin to the Roman tax collector on the far right. We can read the story as three separate moments unfolded in time: an innovative device made easier to follow by St. Peter’s unaltered costume and facial features. Also, notice that the tax collector appears twice for the purpose of continuity. This particular Gospel story would have been a sympathetic subject for the Florentines, who paid high and unpopular taxes to defend the city. The issue of taxation was particularly culturally specific in relation to this work because the Florentine castasto (income tax) was introduced in 1427.

Figure 1.3 | Masaccio, The Tribute Money, c.1425–1428, fresco, 247 × 597 cm, Florence, Santa Maria del Carmine, Cappella Brancacci. Source: akg-images / Rabatti – Domingie.

Figure 1.4 | Francisco de Goya, The Third of May 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, 268 × 347 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado. Source: akg-images / Album / Oronoz.

Modern history: heroes and villainss

The history genre is also applied by art historians to representations of modern historical events. For example, The Third of May 1808, 1814, by Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) depicts invading French troops, under Napoleon I’s command, executing a group of Spanish civilians (see 1.1 Let’s connect the themes: historical perspectives – the Peninsular War). It conveys Goya’s response to Napoleon’s substitution of the Spanish king for Napoleon’s own brother, Joseph, an act of favouritism that led to the Spanish resistance and war.

The Spanish, trapped against a hill, confront their deaths at the hands of a faceless firing squad. The squad, unified in similar dark colours, echoes the resolute and unified stance of the equally determined brothers in David’s Oath of the Horatii; David’s heroes become Goya’s anti-heroes. Goya’s soldiers are machine-like and anonymous, in contrast to the individual faces of the illuminated Spaniards. The central figure stands out in a white shirt and yellow trousers, thereby advancing compositionally. Despite the fact that he is kneeling, he becomes a powerful and oversized presence. The cruciform shape of his emphatically raised hands echoes Christ’s posture at the Crucifixion and the stigmata on his palms are a further reference. The hand furthest from us leads us to the church in the distance. The corpse in the foreground has fallen towards us, arms also outstretched, to forge a connection between the two: the fate of the central figure appears sealed. The formal aspects of Goya’s The Third of May 1808 are examined in more detail in Chapter 4.

Perhaps the most famous twentieth-century example of modern history paintings is Guernica, 1937, by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). History paintings are often large in scale and Guernica is no exception. Its physical monumentality reinforces its epic anti-war message.

Figure 1.5 | Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas, 349.3 × 776.6 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional Reina Sofia. Source: Photo: akg-images / Erich Lessing / Artwork: © Succession Picasso / DACS, London 2015.

Based on the tragedy of the bombing of a small Basque town in Spain, Picasso’s Guernica employs the visual language of distortion, angularity and fragmentation. The latter appears in planes of shallow projection and recession as if collaged. These devices help to convey the chaos of war. The town was bombed by 28 German Bombers (under Hitler’s command and in alliance with Spain’s fascist leader General Franco) during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). This was among the first aerial bombardments in which civilians were deliberately attacked and among the many casualties were women and children. The scene of ruination (see Figure 1.6) clearly had an unprecedented effect upon Picasso as he began his epic portrayal within 15 days of the attack.

A formal analysis of the painting shows the composition moving from right to left, focusing our attention on the bull that looms large in the left-hand corner (which maybe we are meant to interpret as a symbol of Spain), while, just beneath, a mother shrieks with terror as she mourns her dead child; the dismembered corpse of a soldier lies in the foreground, and a panic-stricken horse (possibly representing suffering) gesticulates towards the woman. Their postures are angst-ridden, the engulfing flames signify destruction, the sword in the foreground symbolises defeat, and daggers replace tongues. The eye-like light bulb at the top of the image is reminiscent of the torturer’s cell, but we may also read it as a reminder of the advanced technology that helped bring about destruction, or as a symbol of the all-seeing eye of God, passing judgement.

The horror of the event is represented in Guernica in such a way that it becomes universal. The painting’s monochromatic scheme is reminiscent of the newspaper from which Picasso learnt about the attack, but may also be interpreted as showing the life-destroying meaning of war: draining the emotion, humanity and colour out of life. When we see the cathedral-like ruins shown in photographs of the devastation of Guernica, it heightens the poign-ancy of the historical event and provides us with a sense of empathy with the town’s inhabitants and with Picasso. The photograph shown here could be of any decimated town at any time in history, but this tragedy prompted Picasso to make possibly the most famous artistic anti-war declaration of all time (see 1.1 Critical debates: Guernica’s 2003 cover-up).

Figure 1.6 | Bombing of Guernica, air attack, 1937, Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Bombing of the North Spanish town Guernica by the German Luftwaffe ‘Legion Condor’ on 24 April 1937. Guernica was completely destroyed after the attack. Ruins of destroyed houses after the attack. Photo, retouched, 6/5/1937.

Source: akg-images.

Bridging two genres:‘history’ and ‘portraiture’

Some works of art can belong to two or more genres simultaneously. The Death of Marat, 1793, by Jacques-Louis David is both a portrait of the French political revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat and a record of a historical event – his murder – thereby encompassing two positions in the hierarchy of genres.

In 1789, the storming and destruction of the Bastille (a fortress-prison in Paris) publicly marked French King Louis XVI’s loss of control over Paris and the beginning of the French Revolution. A national assembly was formed to take over the monarch’s leadership and there were riots throughout the region. Every citizen of France was forced into making a political choice. The painter, David, chose to join ranks with the extremist pro-revolutionaries, the Jacobins. David was himself elected to the National Convention in 1792 and voted for the king’s execution. He then devoted his artistic talents to the revolutionary cause and cultivated a severe Neo-classical style that was well suited to the depiction of revolutionary ‘martyrs’, such as the French journalist Marat, associated with the Reign of Terror. From the eve of the French Revolution to the last days of the French Empire, David provided the French state with epic portrayals of the French people. He conveyed great moral lessons to ordinary citizens.

Marat fought the royalists and the bourgeoisie, making many enemies. It was during one of Marat’s many baths – taken to alleviate the irritation of his chronic skin disease – that the young aristocrat and counter-revolutionary Charlotte Corday murdered him with a knife. In the painting, David depicts Marat holding the blood-stained letter by which Corday gained her entry into his apartment. Marat is represented as a modern-day Christ lying in a watery tomb. How does the fact that the artist was both a friend and political ally of the martyred Marat affect his depiction and our interpretation of the work?

Figure 1.7 | Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793 (stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday, Paris, 13 July 1793), oil on canvas, 165 × 128 cm,

Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts. Source: akg-images / André Held.

With the revolution as its backdrop, and Marat as a political martyr, this image may also be explored in terms of its social and historical context. David was commissioned by the National Convention to turn this horrific murder scene into an idealised and pro-revolutionary image; its purpose was pure propaganda. Ironically, Marat, a tyrant to so many, became more powerful when he was dead – a martyr to the revolutionary cause, arguably, aided by David’s depiction of his death.

The work’s style and technique reinforce its content; the naturalistic rendering of the moment of Marat’s death is aided by David’s crisp delineation, chiaroscuro, limited colour palette and static composition. The starkly divided composition focuses our attention: half open (with the void at the top of the composition), half closed (occupied by the figure and his attributes at the bottom). How do you suppose the artist wants us to interpret the unnatural light source entering the scene? Marat appears as the friend of the people, thwarted and dying. He has just finished sending money to a soldier’s widow, the letter he has written on the table reads ‘give this banknote to the mother of five whose husband died defending the fatherland’.

Certain key compositional features in David’s painting also aid the suggestion that Marat, the revolutionary hero, may be seen as a secular Christ – his hanging arm, outstretched like those in representations of Christ deposed from the Cross, draws on centuries of biblical association. Two notable examples you can compare it with are Michelangelo’s (originally Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, 1475–1564) sculpture Pietà, 1498–1499, and Rogier van der Weyden’s painting Deposition of Christ or The Descent from the Cross, 1435.4 Both invest the hanging arm of Christ with the metaphorical weight of sacrifice, and thus this pose has become emblematic of sacrifice throughout the centuries.

I killed one man to save a hundred thousand; a villain to save innocents; a savage wild-beast to give repose to my country.

(Charlotte Corday)

Arguably, Picasso’s Guernica is a more perceptive portrayal of the horrors of human suffering than David’s historical idealisation; although both Picasso and David worked to their own agendas: pacifist and extremely pro-revolutionary, respectively. David’s portrait of the political journalist Marat and the event in history to which it alludes provides an informative bridge between the history genre examined so far and the genre of portraiture which we are about to examine.

Portraiture

Portraits are, fundamentally, pictures of people. That of the assassinated journalist Marat is one example. The genre includes self-portraits, group and individual portraits (these may be face only, head and shoulders or full length), and also includes sculptural portraits, including portrait busts, equestrian monuments and portraits of standing figures such as the life-size bronze portrait/monument to French author Honoré de Balzac, Monument to Balzac, 1891– 1898, cast 1939, by French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). Portraiture dates back to ancient civilisations, but it emerged as an important discipline in its own right during the Renaissance, when the concept that man was made in God’s image gave rise to the celebration of important figures and their individual achievements. Commonly, portraits aimed to depict the external physical features and the character of a person, and provided an important motivation for patronage for centuries (see Chapter 5 for a full exploration and definition of patronage). Private images of less important people tended to be overlooked until the early twentieth century, by which time the hierarchy of genres had lost its significance.

Single portraiture: the portrait as power

Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself Napoleon I, Emperor of France, in 1804 and would govern the nation for a decade. He befriended artists who helped him to promote his image – one might say his myth – and after he became Emperor, images of him in the imperial tradition multiplied.

In his portrait of Napoleon, The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812, David disguises every brushstroke and executes every line with the accuracy of a skilled draughtsman. What effect does such a smooth finish have on our interpretation of the painting? Is it leading us to respond to the image in any particular way? Decorative accessories surrounding the Emperor serve a symbolic function. For example, the books signify learning, the early morning hour on the clock represents the long hours he labours for the people. Consider how the figure and his setting suggest status. His pose, posture, gaze and attributes along with his centrality in the composition, the viewer’s perspective and the gilded chairs all point to his elevated status. His sword, suggestive of military heroism, is put down, just over-hanging the arm of his chair, to signal his more pressing role as law maker. (The Napoleonic Code [on the table] reformed the French legal system to reflect revolutionary principles.) We are made to look up to him, a device that distracts us from the reality of his short stature and ensures our deference to him. The decoration on the furniture refers to Roman Antiquity and opulence, demonstrating a more subtle association with the Roman Emperor than is presented in a slightly earlier work, Napoleon I on the Imperial Throne, 1806, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Figure 1.8 | Jacques-Louis David, The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812, oil on canvas, overall: 204 × 125 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15. Source: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Figure 1.9 | George Gower, Elizabeth I /The Armada Portrait, 1588, oil on panel, 105.5 × 133.5 cm, Bedfordshire, Woburn Abbey. Source: akg-images.

As you can see, a portrait was quite often more concerned with conveying the sitter’s status – his or her wealth, power and position – for commemorative and propaganda purposes, than with conveying an accurate likeness. Our perception of the validity or faithfulness of a portrait also needs to be tempered by the fact that powerful sitters may have had a vested interest in manufacturing their own public identities. Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I of England are good examples of this.

Look at the painting The Armada Portrait, 1588, by George Gower (c.1540–1596) and describe what you can see in the painting. How are the figure and her setting suggestive of power and status?

Painted to celebrate England’s triumph over the Spanish Armada in 1588, the three-quarter length portrait of Elizabeth I, known as The Armada Portrait, uses the event as a backdrop for the monarch and empress of the seas. An extract from her famous Spanish Armada Speech (1588) indicates how convincingly she rallies the hearts and minds of her sailors:

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king – and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms – I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

No doubt the artist, English portrait painter George Gower, considered his patron well in his depiction of her eternal youth. She is dressed in regal splendour and decorated in jewels. Symbolically, she spreads her elegant fingers across the globe, a reference to some parts of the Americas, where she had colonial rule. This is undoubtedly a propaganda portrait: the forward-facing stance, parallel to the picture plane, and the domination of the scene by particularly magnificent sleeves are symbolic of her military achievements. Pearls – a symbol of purity – hang from her proud neck, and an intricate ruff frames her face. With diadem in her hair, and an imperial crown at her side, she conquers both land and sea. Always depicted in her prime, Elizabeth was actually around 55 years old when this portrait was painted. The background gives us two separate stages in the defeat of the Armada: on the left, the English ships challenge the Spanish fleet, and on the right the ships are driven onto the rocks. It seems as if Elizabeth may almost be calling upon the forces of nature themselves. Upon closer inspection you realise that Elizabeth is turning her back on the storm to bathe in the light of triumph on the opposite side, a subtle but effective compositional device; seated loosely on the central vertical axis, she invites our perusal of the two narrative seascapes she separates. As the unassailable monarch of the Tudor dynasty, Elizabeth managed to reign as a woman. Mermaids were believed to have lured many a sailor to their end, and the gilded mermaid carved on the chair in this scene might allude to Elizabeth’s similar ability. Elizabeth, like many other powerful rulers, deployed art to perpetuate and maintain her own cult – in her case, the cult of ‘Virgin Queen’.

Figure 1.10 | Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, oil on canvas, 100.4 × 72.4 cm, the Art Institute of Chicago. Source:The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA / Bridgeman Images / © Succession Picasso / DACS, London 2015.

Elizabeth, King Henry VIII’s child from his second wife, Anne Boleyn, never married, despite many suitors, and never produced an heir. She dedicated herself to developing the prosperity of England, the country she ruled for 45 years.5 Elizabeth’s popularity reached its zenith during her command of England’s defeat over the Spanish Armada. She ascended to the throne when England was impoverished and religiously divided; she died, adored, leaving England as one of the most powerful nations in the world.

While Gower’s portrait of a great Tudor monarch uses accessories and attributes to celebrate his subject’s character, some four centuries later, Picasso set about capturing an altogether different side to his sitter – multiple sides, illusionistically fragmented in space, in fact. Picasso’s Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, one of the foremost art dealers of the twentieth century and early champion of Cubism, illustrates an altogether different style and technique from other images examined under the ‘portraiture’ genre. Unlike any of the other portraits examined so far, Picasso’s has dissolved the form of the figure, fragmenting the lines which conventionally contain it. This half-length frontal portrait epitomises a style known as Analytical Cubism (1909–1912). Linear perspective and chiaroscuro are replaced by faceted planes and a complex tonality; we see the subject from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and tone is not used descriptively but rather to lend a sense of volume – the picture’s surface has been shattered, disrupting the flat, two-dimensional picture plane, and yet the various tones and overlapping forms still suggest three-dimensional depth. Kahnweiler’s form is fragmented to the point of being nearly unrecognisable, save for details such as his moustache, watch-chain and lush hair. He is at one with his background, which includes the effect of perpetually shifting spatial planes; the traditional distinction between foreground, middle ground and background has been eliminated. The tension created between twoand three-dimensional spaces is quite deliberate on Picasso’s part. Picasso, together with his partner in Cubist invention, Georges Braque, sets forth a ‘new reality’– a reality so ground-breaking that to use colour in this painting, or any other analytical works, might be too distracting.

Group portraiture: relationships between sitters

Group portraiture, which includes two or more individuals, may be especially interesting for the viewer to scrutinise, given the added dimension of the relationship between the sitters. Although it only depicts two individuals, the northern Renaissance masterpiece The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, by Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441), is one of the most complicated of all portraits.

Look at the painting The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck and describe what you think is happening in the scene. Do you think the female figure on the right-hand side of the painting is pregnant?

The Arnolfini Portrait, a double portrait, is naturalistically and meticulously painted of a man and a woman standing slightly turned towards each other. This three-quarter view would have been considered more effective than a frontal or profile view in showing their physical volume. This famous painting was, until recently, unanimously agreed to depict the marriage of Giovanni Arnolfini to Giovanna Cenami. However, it has recently been claimed that this could be his cousin and an unknown wife. Multiple readings plague this work while simultaneously maintaining interest in it, and 1.2 Critical debates: matrimony or betrothal? examines some of the different interpretations which have been offered. Whichever Mr. and Mrs. Arnolfini this is, a symbolic reading of the work seems to be the one that many viewers find the most compelling. That question of whether Mrs. Arnolfini is or is not pregnant seems to have been one of the painting’s most alluring features; it’s the first in a sequence of puzzles for the viewer. As well as being fashionable at the time, the abundance of heavy green fabric gathered at her waist becomes an emblem of her cloth merchant husband’s wealth. The chair on the back wall is carved in the image of Saint Margaret, a patron of childbirth and fertility. The dog, whose two-tone hair is painted with such a high degree of verisimilitude, is commonly understood to represent loyalty and provides a fitting comparison with his counter-symbol, the cat, whose appearance as a symbol of infidelity we will discuss later in the chapter.

Until recent alternative interpretations, this work was fairly simple to read in terms of gender roles. She stands away from the window and adjacent to the bed, in keeping with her ‘feminine’ role as housewife. He, bathed in natural light, is closer to the outside sphere, symbolic of his active role in the commercial world. Mr. Arnolfini’s direct gaze confronts the viewer while his wife looks passively and obediently at her husband. His emphatically raised hand signals authority. However, even this gender-based reading has been disputed by a number of art historians and historians, who suggest that she was probably of equal ranking to him under the Burgundian court system (at this time, this region of the Netherlands was ruled by the Duke of Burgundy).

Figure 1.11 | Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, portrait of Giovanni (?) Arnolfini and his wife Giovanna Cenami (?), oil on oak panel, 82.2 × 60 cm, London, National Gallery. Source: National Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images.

Figure 1.12 | Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, detail of chandelier and Van Eyck’s signature on back wall, oil on oak panel, 82.2 × 60 cm, London, National Gallery. Source: National Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images.

That the painting portrays an ‘event’ is supported by the artist’s rather florid statement on the back wall. It is the Latin equivalent of ‘Jan van Eyck was here’. This is testimony not only to the matrimonial act which may have been documented in the painting but also to the changing status of the artist towards the middle of the fifteenth century. Jan van Eyck’s self-publicising ‘graffito’, coupled with what is believed to be the artist’s reflected image in the mirror, marks a more general move towards the recognition of artists in their own right, and is a topic for further discussion in Chapter 5.

Another double portrait, this time from the twentieth century, is Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, painted between 1970 and 1971 by British artist David Hockney (born 1937). Mr. and Mrs. Clark are, in fact, fashion designer Ossie Clark and the textile designer Celia Birtwell. They had only recently married and Hockney, a long-standing friend of the couple, was best man at their wedding. It has been suggested that Hockney drew on The Arnolfini Portrait for his use of symbolism and compositional arrangement. Birtwell and Clark present a reverse formation from Van Eyck’s, with the added predominance of Birtwell over Clark. Hockney presented the work to his friends as a wedding present, suggesting perhaps a further point of comparison with The Ar-nolfini Portrait (formerly known as The Arnolfini Wedding).

Figure 1.13 | David Hockney, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 304.8 cm, London, Collection Tate. Source: ©Tate, London 2015 / © David Hockney.

The lilies in the foreground are positioned close enough to Birtwell to suggest a symbolic association. Lilies, at least since the fourteenth century, appeared in depictions of the Annunciation (the announcement by the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she would become the mother of Jesus Christ, the Son of God) as a symbol of the Virgin’s purity. The Angel Gabriel offers a lily to Mary as he announces that she will bear the Christ Child. At the time of this work, Birtwell was pregnant. Compare the symbolic function of the lilies in Hockney’s scene with those in Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Annunciation, 1849–1850, for example.

In the same way that the Virgin Mary possessed an immaculate soul there is something of the immaculate in Hockney’s style. The acrylic medium, which dries rapidly, suits the purity and minimalism of the couple’s environment. Interestingly, it also helps to create a certain mood. The clarity of the contre-jour light, together with the cool colour-palette, drains warmth out of the room, and arguably contributes to the ‘coolness’ we detect in their relationship: the pair are separated compositionally and stare at us, the viewer, rather than at each other. Could the carefully positioned unplugged telephone indicate a lack of communication between the pair? Their designer objects and clothes are rendered with a distinctly flat quality. Could this reveal as much about their lack of emotional connectivity as it does their celebrity lifestyle? Mrs. Clark stands erect, hand on hip: he sits, leaning back on his chair, in a way that may be interpreted as equally defiant and in opposition to traditions of gendered representation. Consider how this room and the figures’ positions within it compare to Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, examined previously.

Figure 1.14 | David Hockney, a detail from Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 304.8 cm, London, Collection Tate. Source: © Tate, London 2015 / © David Hockney.

Percy, the white cat on Clark’s lap, could be a symbol of infidelity: his carefree disengagement from his environment may be suggestive of his owner’s attitude to extra-marital affairs. Percy follows a long line of symbolic pets in art history. Perhaps the highly charged tail and arched back of the cat in Olympia, 1863, by French painter Édouard Manet (1832–1883) is a pertinent comparison here. Clark was bisexual, and the continuation of affairs during his time with Birtwell is said to have contributed to the breakdown of their marriage in 1974. Knowledge of these facts aids an interpretation of the work, although it can never provide a defining or singular one.

Figure 1.15 | David Hockney, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, 1970, detail of Percy, acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 304.8 cm, London, Collection Tate. Source: ©Tate, London 2015 / © David Hockney.

Manet, Olympia, 1863, detail of the black cat, oil on canvas, 130.5 × 190 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Source: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images.

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy is indicative of a new kind of ‘psychological interior’ that art historian Jonathan Harris suggests pervaded twentieth-century portraiture. In such interiors, objects become ‘signs’ of personality (Harris, Art History: The Key Concepts, p. 242). The kind of psychological tension found in Hockney’s double portrait was captured centuries earlier by French artist Edgar Degas (1834–1917) in his group portrait featuring the Bellelli family, with whom Degas lodged for a period of time in Italy.

The Bellelli Family, c.1858–1860, by French Impressionist Edgar Degas shows the artist’s much-loved aunt, Laura Degas, with her husband, Baron Bellelli, and their daughters Giulia and Giovanna. This detailed and acutely observed scene reminds us of Degas’ classical training at the École des Beaux Arts, and only the hasty exit of the dog from the bottom right-hand corner signals the looseness of his impressionistic-style to come. In fact, the dog’s movement provides an energetic contrast with the stillness of the figures. Compositionally reminiscent of a camera shot, the figures are off-centre. Could this formal element have been used by the painter to convey the family’s dynamic? Find out more about the Bellelli family and look again at the painting in order to reach your own conclusions.

Figure 1.16 | Edgar Degas, The Bellelli Family, c.1860, 2 × 2.5 m, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Source: The Art Archive / Musée d’Orsay Paris / Gianni Dagli Orti.

Mrs. Bellelli forms a dark and austere pyramid to the left of the composition, and we perhaps follow her fixed gaze beyond her sedentary and rather disconnected husband to a window, a space beyond the one she occupies. Mrs. Bellelli appears to be supported by her eldest daughter Giovanna, who, aged only ten at the time, already mimics her mother’s restraint and formality. A further, less obvious, support is achieved by Mrs. Bellelli’s tensely arched hand which props itself on the table’s top to reveal a clearly visible wedding band. Her black dress reminds us that she is mourning for her late father, Hilaire Degas, whose portrait hangs next to her on the wall. Hilaire, alive only in the red lines that depict him, appears to stare purposefully at the baron. How should we interpret this?

While Giovanna is buttoned up to the neck and well-groomed like her mother, the youngest daughter, Giulia, reveals a subtle unwillingness to conform for the sake of social responsibility and hides one leg under her chair. How can this deliberate disruption to the formality of the scene be understood? Giulia occupies the centre of the composition – caught between two warring factions perhaps. What do you think? Whose kindred spirit is she?

By virtue of the multiple figures present in group portraiture, the sub-genre is often rich in detail and symbolism. Spanish artist Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, c.1656, is certainly no exception. See 1.3 Explore this example.

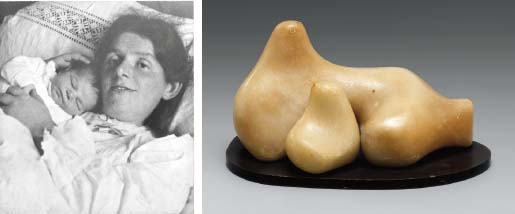

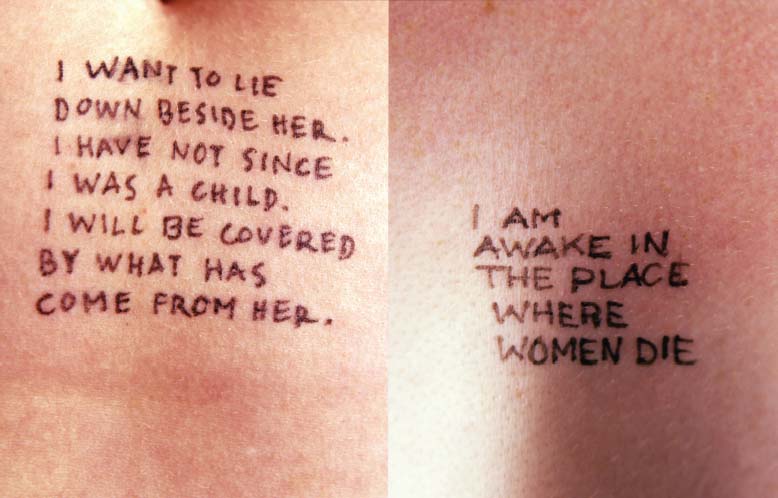

Self-portraiture: suffering and confrontation

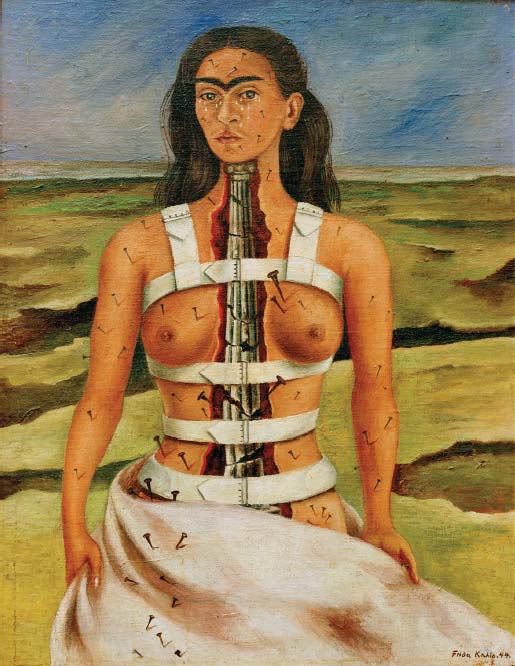

A self-portrait may be a portrait of the artist by himself or herself, or included in a group. Self-portraits have a long history, although it was not until the mid-fifteenth century that painters took themselves as their subjects in earnest. The self-portrait can also be used for the purpose of self-promotion. Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) is probably best known for her self-portraits, many of which art historians have read as depictions of her suffering from the physical pain of longterm health problems and the emotional pain associated with her marriage to prominent Mexican painter, Diego Rivera.

Figure 1.17 | Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944, oil on canvas, mounted on hardboard, 40 × 30.7 cm, Mexico City, Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Xochimilco. Source: akg-images / © 2015. Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / DACS.

I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

(Frida Kahlo)

A metal rod pierced Kahlo’s abdomen in a horrific tram accident when she was a teenager, fracturing her spine and destroying any chance of her later bearing children. The Broken Column, 1944, is confessional of the life-long pain she experienced following the accident. Her sense of isolation is conveyed in this vast, barren landscape and her physical suffering conveyed in tears like those of the mater dolorosa (a Christian title used for the Virgin Mary, meaning ‘our lady of sorrows’). Her body is visibly broken open, and the splintered, Ionic column represents her broken spine and the brace which supported her back. This self-portrait, like so many others in her oeuvre, depicts the artist in a frontal pose, maintaining direct eye-contact with the viewer under a heavy and distinguishing mono-brow.

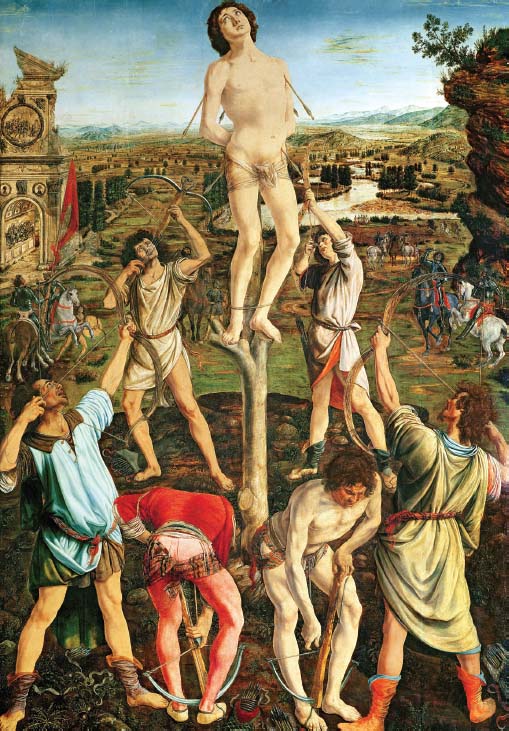

Her nakedness only heightens her vulnerability although, arguably, Kahlo’s shroud-like drapery is an allusion to religious suffering. Her eyes express courage, and her depiction is more than faintly reminiscent of the Ecce Homo or the martyrdom of St. Sebastian, her nails a substitute for his arrows. A good comparison might be to The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, 1473–1475 by Italian Early Renaissance painters Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1432/3–1498) and Piero del Pollaiuolo (1441–1496).

Complicating Kahlo’s representation of herself as a brave and tragic figure is the frequently suggested idea that the artist consciously forged a strong and schematic identity, which aided the perpetuation of her own fame and status as an artist. Kahlo’s artistic self-preoccupation finds a parallel with that displayed by other artists, as seen for example in the Christ-like Self-Portrait, 1500, by German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) (see Figure 5.4). Dürer epitomises the theme of the changing status of the artist; his ambition, declared almost blasphemously, in this self-portrait, represents unprecedented self-aggrandisement on the part of the artist. We could argue that Dürer’s Self-Portrait as Christ marked the start of the artist as celebrity.

Figure 1.18 | Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo, The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, 1475, oil on poplar, 291.5 × 202.6 cm, London, National Gallery. Source: National Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images.

Dürer’s Self-Portrait (see Figure 5.4) is best understood in the context of humanism. Humanism emerged in Classical Antiquity and focused on people’s intellectual capacity and ability to achieve great things. It was resurrected in Italy during the Renaissance, where it became a sign of progress and development. Religion had by no means lost its significance during the Renaissance, but humanism was a parallel concern that celebrated the achievements of God’s creation in the form of humankind. Dürer was heavily influenced by the Italian Renaissance and played a key role in the development of something like a northern equivalent in Germany. During the Renaissance it was still uncommon for artists to sign their works and even less common for artists to paint themselves as their subjects. In this sense, Dürer’s Self-Portrait, which appears to imitate Christ, is ground-breaking on a number of levels.

The severed head in David with the Head of Goliath, 1609–1610, by Caravaggio (originally Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571–1610) is a rather atypical self-portrait of the artist. In May 1606, Caravaggio was accused of murdering a young Roman, Tomassoni, following a trivial argument. With a price on his head for murder, Caravaggio fled Rome, travelling to Naples, Sicily and Malta. This self-portrait as Goliath’s severed head demonstrates an unconventional plea for forgiveness. Although the pardon was granted, tragically, Caravaggio was dead before he received the news. Maybe David’s loose grip on his sword and his piteous face prophesy a tragic ending? The narrative unlocks the artist’s use of a number of devices. David’s expression of sad resignation fosters sympathy in the viewer for an artist ruined by his own tempestuous nature. David’s face is illuminated from the tenebristic background, possibly providing both a divine authority for Goliath’s execution and a guarantee that we understand the sub-text. Is Caravaggio emerging from the darkness and awaiting judgement? David with the Head of Goliath is, according to journalist and art critic Jonathan Jones, perhaps the truest painting ever done of death (Jones, ‘The Complete Caravaggio Part 3’). What was painted as a gesture of apology becomes a tragedy of Shakespearean proportion.

Figure 1.19 | Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (with Self Portrait of the Artist as the Dead Goliath), 1609–1610, oil on canvas, 125 × 100 cm, Rome, Galleria Borghese. Source: akg-images / Nimatallah.

Self-portraiture became increasingly less naturalistic from the end of the nineteenth century, and artists such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) found ways to reveal their personal states of mind using interior and landscape settings, expressive brushwork, arbitrary colour and other devices. Mark Quinn’s Self, 1991, made with the artist’s own blood, is a self-portrait in twentieth-century terms.

Genre

Figure 1.20 | Jan (Johannes) Vermeer, The Milkmaid, c.1660, oil on canvas, 45.5 × 41 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. Source: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands / Bridgeman Images.

As well as meaning ‘type’, the word ‘genre’ also refers to scenes depicting the everyday life of people. Thus, in accordance with the ‘hierarchy of genres’ outlined by Félibien in the seventeenth century, the genre-genre suffered a low ranking, following the history and portraiture genres previously examined. Genre paintings often provided a counterpoint to the more serious and academic history genre. Genre works are a category of art that tends to depict realistically scenes of everyday life such as street scenes, markets or domestic interiors as shown in The Milkmaid, 1660, by Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675). Genre scenes characteristically feature figures and are distinguished from other genres such as portrait and history on account of their depiction of ordinary people and unidentifiable people. Genre scenes flourished in northern Europe, and Vermeer specialised in their perfection.

‘Genre’ scenes: everyday life

Demonstrating a characteristically introspective study of a milkmaid at work, the artist’s mastery of light brings every conceivable texture of this scene to life. Employing a variety of impasto effects, we almost feel the roughness of the bread’s crust scratching our mouths and sense the milk slipping over the glazed rim of its terracotta vessel. The maid appears unaware of us and yet we feel as if we were right there with her, due to the artist’s technical verisimilitude and realistic quality of light. This mundane, low-life scene testifies to the represented woman’s virtue: she is making a pudding to nourish others and her strength of character is reinforced by her physical mass. We could interpret the grainy quality of the light which enters the room through the window on the left, coupled with the heavenly blue of her apron, as spiritual. Genre works tended to observe objects and people as though through a virtual microscope, demonstrating the meticulous attention to detail and surface texture, to the clothing and setting. Vermeer masterfully demonstrates his ability to render the intangible quality of natural daylight in this intimate space: he shows us light reflected in the glazed pot, light absorbed by the maid’s clothes, and light as a quasi-religious shaft pouring through a broken pane in the window.

A far more crowded ‘genre’ scene is provided by the nineteenth-century painting Omnibus Life in London, 1859, by William Maw Egley (1826–1916). As a new form of transport, the (horse-drawn) omnibus gave Egley the opportunity to depict the social and historical context of the Victorian era within this claustrophobic interior. This genre scene, comically packed to capacity, provides the viewer with an insight into the social hierarchy of London’s emerging travel system.

Figure 1.21 | William Maw Egley, Omnibus Life in London, 1859, oil on canvas, 44.8 × 41.9 cm, London, Tate Britain. Source: © Tate, London 2015.

The viewpoint the artist has chosen makes it seem almost as though we are entering the carriage ourselves, a probability made more likely by the quizzical glare of the fashionable little boy wriggling in his mother’s arms. Every object is rendered with meticulous detail and is suggestive of meaning in some way. What do you think the objects say about social class and status? The carriage has been described as conveying ‘a variety of social types’; however, omnibus travel was still relatively expensive and tended to attract middle-class commuters (Treuherz, Victorian Painting, p. 109).

Figure 1.22 | Edgar Degas, In a Cafe or L’Absinthe, c.1875–1876, oil on canvas, 92 × 68 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Source: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images.

There is also the suggestion that the coach represents a series of binary oppositions which provide a form of sub-text prevalent in British society at this time. For example, the juxtaposition of young and old, male and female, and, more subtly, exterior and interior, and watched or being watched. This is precisely the kind of societal contrast being acutely observed by some of the most famous writers and playwrights of the nineteenth century.

The crowds of people represented in microcosm in Egley’s omnibus embody a duality that would fascinate nineteenth-century artists. The crowd was both a depraved and gleeful source of life itself – [f]or Baudelaire the phenomenon of the crowd is the manifestation of modernity itself (Schnapp and Tiews, Crowds, p. 345). Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), poet, critic and the ultimate spectator of modern life, embraced the epic quality of contemporary living and championed the ‘new reality’ depicted by Manet and the Impressionists. In his 1845 Salon Review, Baudelaire describes the modern artist’s ability to capture the transience and modernity of the times in a manner which rivals the ‘epic’ works of the ancients: There is no lack of subjects, or of colours, to make epics. The painter, the true painter for whom we are looking, will be he who can snatch its epic quality from the life of today (Baudelaire, Art in Paris 1845–62: Salons and Other Exhibitions, p. 32). Baudelaire wrote about, and Manet and the Impressionists painted, both sides of modern life: the socially enjoyable and the socially and economically deprived.

In L’Absinthe, 1875–1876, a genre scene of Parisian life by Edgar Degas, two miserable absinthe drinkers represent a significant aspect of urban life. During the nineteenth century, hordes of people migrated into the metropolis in search of work. The ‘phenomenon of the crowd’ was born together with, ironically, a new and modern sense of isolation. Life in the city was overcrowded and squalid; unsurprisingly, alcohol consumption, particularly absinthe, had become the recreational pastime of the working-classes. Photographic techniques had been honed by the 1850s and the camera’s ability to capture the immediate and the real is evident here. The composition of the painting is cropped almost like a photograph, helping the work seem modern and up to date, and perhaps contributing to its sense of realism and actuality. It heightens our sense of the transient and, in so doing, captures a Baudelairian sense of modernity. Degas’ L’Absinthe and the social and historical context of mid-nineteenth-century France is examined in more detail in Chapter 4.

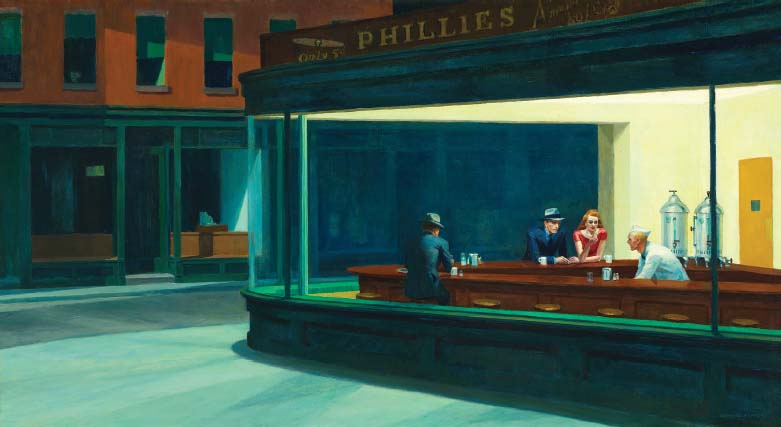

As well as being an example of the genre-genre in a later era, Nighthawks, 1942, by Edward Hopper (1882–1967), offers an equally sombre insight into the period of its production and, for that reason, also appears in more detail in Chapter 4.

Look at the painting Nighthawks by Hopper and describe the figures and their setting. What type of mood has the artist conveyed in the painting and how has he achieved this?

This scene of American life, painted in 1942, characterises Hopper’s haunting style. Muted tones compromise its realism and signal its sub-text. An airless quality seems aided by the superficially rendered space and graphic quality of the painted surface. The physical window that separates the diners from the area outside appears to mirror the psychological barrier that distances them from us as viewers, locking the depicted figures deeper into a helpless and parallel plane. Ironically, the figures are isolated from one another, despite occupying a social space, and this contributes to the ‘eeriness’ of the scene.

Figure 1.23 | Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas, 84.1 × 152.4 cm, Friends of American Art Collection, 1942.51, the Art Institute of Chicago. Source: Photography ©The Art Institute of Chicago.

Landscape

Figure 1.24 | Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews, c.1750, oil on canvas, 69.8 × 119.4 cm, London, National Gallery. Source:The National Gallery, London / akg-images.

Landscape is a broad term, especially in the hands of artists, and its low ranking in the hierarchy of genres established in the seventeenth century, bears little or no relevance today. Traditionally, it relates to our natural, rather than man-made environment, although these categories are not always easily distinguished. Landscape can also include scenes of human activity. Landscapes are not always faithful representations. Depending on the period of their creation, landscapes can represent an idealised ‘myth’ of the land, or an expression of national pride, or perhaps subjective emotional and even abstracted representations.

Owning and working the land

The double portrait of Mr and Mrs Andrews, c.1750, by English painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) is unusual as it is also a landscape. More complex landscapes can represent two or more genres when they incorporate figures, especially recognisable ones. The Suffolk squire, Robert, and his wife, Mary, look incredibly pompous in the knowledge that we are made to survey their land. His casually crossed legs and slightly raised brow imply he’s brimming with rural-aristocratic complacency – he owns the land and has the ability to control it with use of the latest technology of that time.

In his The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689, Dutch artist Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709) offers us a view of a quintessential Dutch avenue. Weathered poplars guard man-made tracks in the broad Dutch landscape, leading our gaze to a villager on the path and beyond him to the horizon line (where the sky meets the land). Compositionally, the land is divided into two parts by the central road which we appear to be travelling along too, albeit in a slightly elevated position. The left-hand side is slightly more unkempt and natural: the righthand side is highly structured and ordered by man’s honest labour. The low horizon line is typical of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape, as is the panoramic view; both devices remind the viewer of humans’ relationship with their natural environment and its importance to the Dutch Republic at this time. (See 1.2 Let’s connect the themes: historical perspectives – land reclamation project.)

Figure 1.25 | Meindert Hobbema, The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689, oil on canvas, 103.5 × 141 cm, London, National Gallery. Source:The National Gallery, London / akgimages.

Landscape can also convey a sense of national pride. In this sense, landscape could be said to express prevailing ideology and social values. It certainly expressed the dominant social control of the bourgeois landowners in Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews.

Landscape as emotional expression

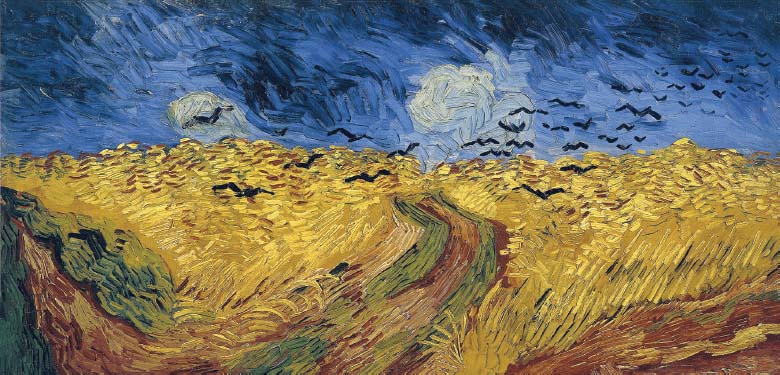

Landscape is as much born from its context as any other genre in the history of art. Whether seen through a scientific lens in the seventeenth century, or through an expressionistic and individualistic one in the nineteenth century, it never fails to provide an insight into the times of its production. In 1883, German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche famously professed ‘God is dead’ as part of his increasingly pessimistic view of the world. The Nietzschean belief that life lacks purpose could be related to Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, for example.

Dutch Post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) used landscape and, most notably, colour to express his feelings. In viewing Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, we become a part of the ‘topsy-turvy world’ he depicts. Painting in the nineteenth century, Van Gogh was one of the first to express his interior as opposed to his exterior view of the world; however, in the twentieth century, the landscape was often used as a conduit for the communication of artists’ suffering and angst. Although the region of Auvers, France, where this painting was made, initially offered him peace, towards the end of his time he was increasingly prone to bouts of temper, possibly as a consequence of a form of epilepsy from which he appears to have been suffering. It appears that the artist shot himself in a lonely field on 27 July 1890 and died the morning of the 29th.6

Van Gogh’s technique involved the rapid application of paint, in thick impasto, and each stroke carries a sense of urgency: the wheat seems to thrash about in various directions and the paths seem to move just as organically, suggesting instability and uncertainty. We sense that those menacing crows, age-old symbols of doom, may encircle us soon. In this painting, the turbulence of the artist’s mind manifests itself in the violence of his brushwork. Characteristically, colour is the artist’s main symbol of expression: the uppermost sky turns from blue to black, creating an ominous mood over the field. Wheatfield with Crows is arguably the most agitated of his works and it is tempting to read it as his suicide note given its execution so close to his death. Although some have suggested that this was the ‘last’ work the artist painted, what we know for certain is that it was one of his last. Van Gogh painted a series of landscapes leading up to his death about which he wrote, rather prophetically:

They are vast stretches of wheat under troubled skies, and I did not need to go out of my way to express sadness and extreme loneliness. (Roskill, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh, p. 338)

Landscape may also be a reminder of nature’s power to inspire awe and metaphysical wonder. American painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) became interested in anti-academic, non-traditional art and was increasingly concerned with nature in its purest form; she attempted to represent the underlying essence of things. We know that O’Keeffe read Wassily Kandinsky’s 1911 publication Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which proposed that artists could lead humanity to spiritual enlightenment.

Figure 1.26 | Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, oil on canvas, 50.5 × 103 cm, Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum. Source:Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands / Bridgeman Images.

Deer’s Skull with Pedernal, 1936, set in an infinite and barren landscape, may be seen as reminiscent of the Crucifixion. The viewer is provided with a low perspective which forces our gaze upwards in an act of veneration – these are the bones of once-living creatures bleached white under the searing heat of nature’s sun; to the artist, these are the bones indicative of nature’s wondrous power. O’Keeffe travelled to New Mexico in 1929 and its vast space overwhelmed her. The interminable blue sky and swollen rhythms of the hills are as significant as the bones themselves. In the same way that synaesthete Kandinsky’s blindingly colourful compositions were designed to affect our very soul, O’Keeffe’s oeuvre became increasingly bound up with the idea of its Almighty creation – and the search for a quasi-religious universalism in her art. O’Keeffe’s painting is an atypical landscape insofar as it is also a form of exterior still life; however, it is the might of God’s nature, a nature evident in the landscape, that O’Keeffe observes.

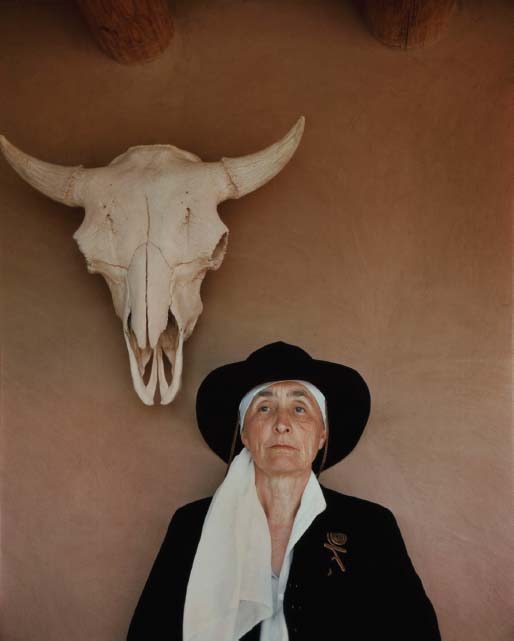

Figure 1.27 | Philippe Halsman: Georgia O’Keeffe at her desert ranch, 1948, Abiquiu, New Mexico. Source: © Philippe Halsman / Magnum Photos.

The landscape genre, in common with every other genre, has evolved a great deal over the centuries. While it has been used to reveal the status of its landowners and the relationship between man and nature’s infinite might, it has also been used by modern artists unconventionally, even as a form of self-portraiture, as is the case with Sam Taylor-Johnson’s (formerly Sam Taylor-Wood) photograph Self-Portrait as a Tree, 2000.7

The landscape in Western art seems to have fallen in and out of favour over the centuries. It emerged during the Renaissance as a convincing backdrop to scenes enacted from the Bible or from mythology, and continued to grow in stature during the sixteenth century. By the seventeenth century, landscape was recognised as being a valuable genre in its own right. In the nineteenth century, the landscape provided experimental ground for a variety of avant-garde movements.

Figure 1.28 | Georgia O’Keeffe, Deer’s Skull with Pedernal, 1936, oil on canvas, 91.4 × 76.5 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of the William H. Lane Foundation, 1990.432.

Source: Photograph © 2015 Museum of Fine Arts. Boston / © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / DACS, 2015.

Still Life

Figure 1.29 | Harmen Steenwyck, An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life, c.1640, oil on oak, 39.2 × 50.7 cm, London, National Gallery.

Source:The National Gallery, London / akgimages.

Still life, devoid of human figures and more demonstrative of artistic skill than imagination and intellect, was considered relatively unimportant in the hierarchy of genres. Still life commonly refers to paintings depicting a selection of everyday objects such as fruit, flowers, utensils and collectors’ items, which may have been painted both for the intrinsic value of their form and in order to infuse the objects with symbolism (often religious). Still life paintings were traditionally small in scale, in accordance with their status and likelihood of hanging in a private dwelling.

Memento mori

Seventeenth-century Flemish and Dutch painting, such as An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life, c.1640, by Harmen Steenwyck (1612–1656), excelled in this genre. Objects were carefully chosen for the senses they evoked. Delicate materials such as the paper and the shell were common, not least for their reference to the fragility of human life. The skull acts as the ultimate reminder of mortality also known as memento mori. Thus, this painting is essentially a religious work in the guise of a still life. Vanitas are examples of still life with religious overtones, and often are concerned to point the viewer towards an awareness of his or her own mortality. Vanitas paintings prick the viewer’s moral conscience and warn them to be careful about placing too much importance on the materiality and pleasures of this life, as they could prevent salvation in the next, so communicating the message summarised in the Gospel of Matthew: Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also (Matthew 6:18–21).

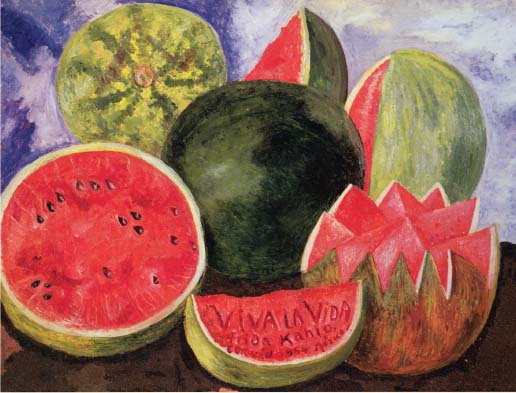

Viva la Vida, 1954, is one of Frida Kahlo’s last works. Having endured multiple surgeries spanning many years, in 1953 gangrene set into her right foot and her leg had to be amputated below the knee. The impact of this final surgery was devastating. The event precipitated this image as a diary entry, and with the usual and humorous tone she writes Pies para que los quiero, si tengo alas pa’ volar? (Feet, what do I need them for when I have wings to fly?) The blood-red fruit in this painting may reflect the pain she suffered, and the jagged cuts in the watermelon suggest the numerous surgeries she endured. The fruit lays bare its fleshy interior, ripped open, as she was. She died the same year Viva la Vida was painted, seven days after her 47th birthday.

Viva la Vida is often discussed as a vehicle for the artist’s national pride. By selecting only locally grown produce, she made the fruits of the earth symbols of her. The red, green and white colour scheme represents the national colours of Mexico and their intensity echoes the national pride felt by an artist who changed her birth date to coincide with that of the Mexican Revolution. This work makes a fruitful comparison with Steenwyck’s, a connection only made clear with an autobiographical reading of Kahlo’s work. Both are memento mori; Steenwyck’s overtly, in relation to its metaphorical objects; Kahlo’s covertly in relation to her deteriorating health and sense of her own nearing departure from this life. Kahlo’s work, and the impact of her Mexican nationality upon it, is examined in more detail in Chapter 6.

Figure 1.30 | Frida Kahlo, Viva la Vida, 1954, print, Private Collection. Source: Private Collection / Bridgeman Images / © 2015. Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / DACS.

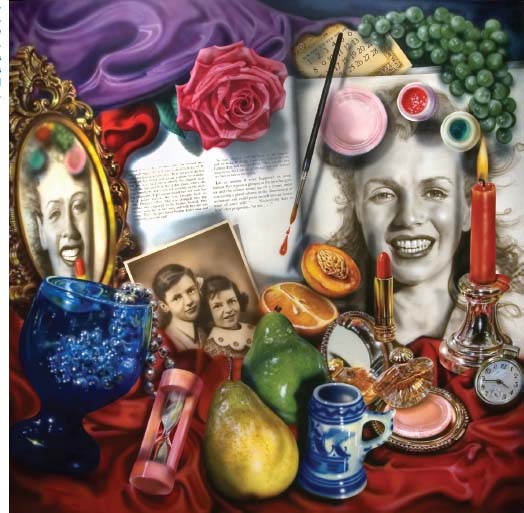

Figure 1.31 | Audrey Flack, Marilyn (Vanitas), 1977, oil over acrylic on canvas, 244 × 244 cm, the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Source: Collection of the University of Arizona Museum of Art; Museum Purchase with Funds Provided by the Edward J. Gallagher, Jr. Memorial Fund. / Courtesy of Louis K. Meisel Gallery.

Superrealism is a style that emerged in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, and is synonymous with (sometimes also called) Photorealism and Hyperrealism. It is characterised by an unnerving and incredible level of realism. Superrealist artists often imitate photographs in paint, and many of the qualities associated with a photographic image are replicated in Superrealist images, such as varying focus and a frozen image effect.

One of the pioneers of photorealism, American artist Audrey Flack (born 1931), presents in Marilyn (Vanitas), 1977, a Superrealist still life as a modern-day allegory of the transience of life: a kitsch hour-glass in bubblegum pink metaphorically reminds us of time’s passing, as do the other traditional vanitas objects: the candle and the fruit. The latter is so ridiculously waxed and obviously fake, it forces us to think beyond the superficial for a moment. The fruit, the lipstick, the pearls are all adornments, accessories and ‘signs’ of our modern age – an age defined by its consumption and commodification. As well as alluding to traditional seventeenth-century vanitas paintings, Flack updates the genre with the inclusion of a calendar, a modern object, although suitably symbolic of the transience of life and referring back to traditional images of the labours of the months.

The work’s main subject, the American icon Marilyn Monroe (1926–1962) smiles as if for a publicity shot, possibly reminding us that she was consumed by her own media-made persona. Typecast as a ‘dumb blonde’, packaged and sold, she wound up as a ‘probable suicide’ victim. Little wonder that Andy Warhol used her image in the 1960s in one of a series of ‘mass produced’ images of celebrities. Marilyn’s image is surrounded by the kinds of luxury objects that denoted her life, and yet this work becomes almost commemorative of her death. Some objects appear in sharper focus than others and this is as a result of Flack’s technique: she projects the image onto the canvas and paints over it, creating an exact replica of the photographed image. How does the inaccurate perspective alter your perception of the scene? A sepia-toned photograph of the artist and her brother nestle among the objects, forging a connection between the transience of Monroe’s life and the artist’s. The main image of Marilyn on the right depicts her beauty but is reflected and distorted in the mirror on the left. What do you think this could mean?

Flack’s technique of projecting her image onto canvas and then painting it may reinforce a lack of authenticity theme. Photorealism is all about illusion after all. The paradoxical relationship between the ‘false’ and ‘true’ elements of this picture – the real Marilyn: the false persona; the real photographs: the false fruit – remind us that the hierarchy of genres and fixed rules in art were laid to rest in the early twentieth century by a series of avant-garde pioneers, most notably Picasso. Once relegated to the lowest rung in the hierarchy of genre, ‘still life’ has proven to be an enduring subject for artists. Despite being three centuries apart, the technical expertise of Flack’s twentieth-century Marilyn (Vanitas) has much in common with Steenwyck’s seventeenth-century Vanitas, and both paintings challenge the viewer on a number of moral and intellectual levels.

Subjects

Figure 1.32 | Elisabeth Frink, Walking Madonna, 1981, bronze, height 182 cm, Salisbury

Cathedral. Source: © Kevin George / Alamy / © Estate of Elisabeth Frink. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015.

Subjects as a category may seem slightly confusing in its relation to genre, since genres consist of subjects, but there are so many varied subjects that they reach far beyond the confines of the hierarchy of genres. Perhaps the easiest way to settle their distinction is to view the genre as describing what a painting is (its category) and the subject as what it is about, or what it depicts.

Religious subjects

In this context, religious subjects are drawn from the Western world where Christianity was historically the dominant religion. Images are commonly drawn from Christian stories in the New Testament, such as the Crucifixion and Entombment of Jesus, together with other narrative scenes from His life; however, not all biblical works are based on narrative. Images of the Virgin Mary tended to be most widely depicted in the art of Catholic countries such as Italy. Christian images are almost as old as Christianity itself and it was not until the Italian Renaissance in the early fifteenth century that secular subjects became more commonplace. In modern times, religious art has tended to be less motivated by devotion than by aesthetics. As mentioned previously, stories and figures from the Bible can be included under the ‘history’ genre; however, they can also be treated as a subject in terms of having religious subject matter.

Madonnas

Unexpectedly positioned walking away from Salisbury Cathedral, the Walking Madonna, 1981, is the sole female in English sculptor Elisabeth Frink’s (1930–1993) oeuvre. A strong female type, based on Frink’s own face, strides away from the security of the church, her emphatic arms providing a sense of dynamism and self-reliance. She exudes a purposefulness that may be interpreted as intimidating. Atypically, this is a post-resurrection Madonna, perhaps an exemplar for the guidance of faith in a new and often doubting world. The sculpture is perhaps also semi-autobiographical, depicting the artist’s strength of character and artistic independence. Look at photographs of the artist’s distinguishing features and see what you think.

Portrayed as striding, strong and self-reliant, perhaps one only recognises the extent of Frink’s innovation on an age-old theme when we compare her Madonna with the iconic Pietà, 1498–1499, by Michelangelo (1475–1564). Commissioned for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the most important church in Christendom, Michelangelo carved his name onto the Virgin’s sash to ensure he received credit for the masterpiece. This Madonna is widely regarded as an idealised beauty whose serenity is unparalleled. Her tiny frame supports the adult Christ with exquisitely carved drapery. This Virgin is dignified in mourning and her upturned-hand gesture signals the stoic resignation of her loss; she makes her own sacrifice of her son in counterpart to Christ’s greater sacrifice. In this sense she provides a stark contrast with Frink’s Walking Madonna in terms of material, technique, process, demeanour and effect on the audience. Not least, Frink expresses her interpretation of Christ’s mother as symbolic of all powerful women, real women; in contrast, the Renaissance biographer Vasari congratulated Michelangelo’s Pietà on its idealised representation of Mary: To be sure, there are some critics, more or less fools, who say that he made Our Lady look too young. They fail to see that those who keep their virginity unspotted stay for a long time fresh and youthful (Vasari, Lives of the Artists, p. 337).

Figure 1.33 | Michelangelo, Pietà, 1498–1499, marble, height 174 cm, base 195 cm, depth 69 cm, Rome, St. Peter’s Basilica. Source: © 2015. White Images / Scala, Florence.

The gender of the respective artists, together with the contexts within which they made their works, is bound to have influenced these polarised representations of the same religious subject. Reverential religious iconography prevailed throughout the Renaissance; not until the arrival of Caravaggio in Rome did it become controversial.

Representations of Christ

Having already established that scenes from the Bible such as the Crucifixion, Entombment and Resurrection could be used in so-called ‘history’ painting, it may be surprising to learn that Caravaggio’s Entombment, 1602–1604, has been categorised as a religious subject here. However, it may be that the artist’s somewhat controversial interpretation of the scripture undermined any claims this image might have to occupancy of the highest genre. Commissioned as a monumental altarpiece for Santa Maria Vallicella, the painting typifies the form of Baroque style which can be referred to as naturalistic. A pyramid formation liberates it from the strict equilateral triangle typical of the Renaissance (exemplified by Michelangelo’s Pietà), to form a diagonal composition from the splayed fingers of Mary of Cleophas (whether this figure is Mary Magdalene or Mary of Cleophas is debated), top right, to Christ’s equally illuminated white shroud trailing over the stone slab, bottom left. The figures emerge theatrically from a tension-filled and tenebristic background. Christ’s mourners are bent over in an undignified way, and the painting is cropped at the top, perhaps to heighten their claustrophobic sense of grief. English journalist and art critic Jonathan Jones observes:

Figure 1.34 | Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1602–1604, oil on canvas, 300 ×203 cm, Rome, Pinacoteca Vaticana.

Source: akg-images.

Figure 1.35 | Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, detail of Mary’s face, 1602–1604, oil on canvas, 300 × 203 cm, Rome, Pinacoteca Vaticana.

Source: © 2015. Photo Scala, Florence.

The actors in his paintings are recognisable as actual people – often you can follow the same model from one canvas to another, posing now as Cupid, now as Saint John. They are not well-to-do people either. They are the scum of the city – prostitutes, rent boys, beggars. Caravaggio’s marginal existence is fully reflected in his art, its drama conveyed by his extreme optical style, all brightness and blackness. (Jones, ‘The Complete Caravaggio Part 1’) With Caravaggio’s characteristic realism, the Virgin’s face is depicted as old (see detail) and bears no resemblance to the unsullied beauty of Renaissance Virgins.

The image of Christ by American photographer Andres Serrano (born 1950) would have been inconceivable in Caravaggio’s seventeenth century, and it was still considered controversial in the more secular 1980s. Serrano created the transcendental and visually spectacular photographic image Piss Christ, 1987, by submerging a small plastic image of Christ in a glass of his own urine, and photographing it from a close-up and raking angle. The work caused public outrage, which is something it has in common with The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, by British artist Chris Ofili (born 1968), which mixes holy iconography with pornography in order to make a powerful social statement.

The nude

The nude has become one of art history’s most enduring subjects and is rich terrain for exploring themes of gender and racial stereotypes, as well as culturally specific ideals of beauty. While the female nude has been invested with iconic status and has become synonymous with gallery visits and perhaps even art history itself, the civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome had an unparalleled aesthetic appreciation for the beauty, musculature and strength of the naked male form, and heroes, athletes and gods were commonly depicted unclothed.

Religious and mythological nudes

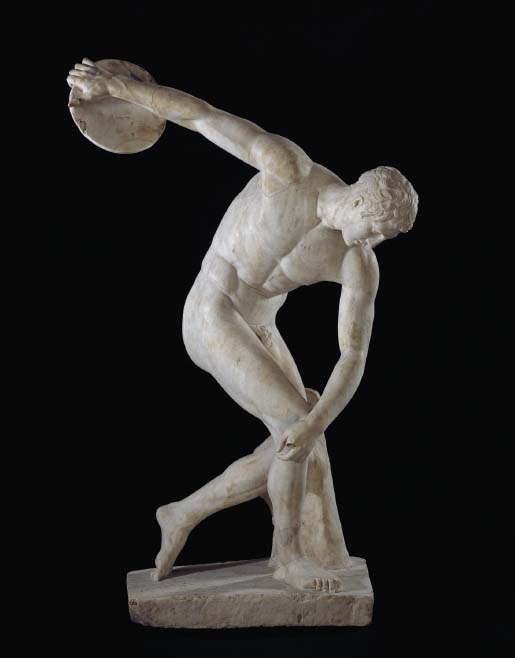

The Greek sculptor Myron of Eleutherae is known to have created a bronze sculpture of The Discus-Thrower in about 450 bce, but all that remains are copies made in Roman times. Caught in the flush of youth, the figure is an idealised male nude captured in athletic contrapposto and rendered anatomically correct, if idealised, by its sculptor. His limbs, positioned in perfect equilibrium, suggest a restrained dynamism and overall harmony. Discobolus is one of many male nudes that comprise the masculine statuary of Antiquity. Athletes who took part in the games at Olympia (the site of the Olympic Games in Classical Greece) were said to compete naked (gymnastics comes from the word gymos, which means ‘naked’ in Greek). These men, considered the acme of male beauty, often doubled as soldiers and defenders of the polis (the state).

Figure 1.36 | The Discus-Thrower (Discobolus), Roman copy of a bronze original of the fifth century bce, 152 cm high, from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Lazio, Italy. London, British Museum.

Source: ©The Trustees of the British Museum.