Chapter 4

Social and Historical Contexts

Introduction

This chapter introduces you to the theme of social and historical contexts and considers how works of art or architecture reflect the times in which they were made, or were influenced by a particular social or historical event, events or circumstances. Historical context means the political, cultural, economic and social circumstances in which a work of art or architecture was created. Relevant historical conditions or events may include wars, scientific or industrial developments (such as the Industrial Revolution), political revolutions, and economic booms and busts. Typically, social and historical contexts are closely inter-related and provide a broad perspective on ‘what is going on’ in society at a particular time in its history. Social context means the social conditions and popularly accepted beliefs in a society at a particular time, such as attitudes relating to gender or class.

Chapter 3 examined the formal features of works of art and architecture regardless of the subject matter and irrespective of the work’s social and historical contexts. In contrast, this chapter prioritises the broader contexts in which the art was produced as the basis for its formal aesthetic or style, and considers the multitude of variables that may permeate a work’s production and contribute to the meaning we assign to it.14

Many of the works already discussed in previous chapters may be further scrutinised under the lens of social and historical contexts. For example, Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat, 1793, first examined in Chapter 1 as an example of the history and portrait genre, will be explored in relation to the social and historical contexts of the French Revolution and the political ideology of the National Convention that ruled France during the king’s removal from power.

This chapter will illustrate the significance of context in relation to the seventeenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a focus, although readers have the freedom to select examples from Western art and architecture from Classical Greece to the year 2000.

Seventeenth Century:Baroque Rome and the Catholic Counter-Reformation

The Baroque style that originated in Rome during the seventeenth century spread throughout Europe to Flanders, Spain, France, the Dutch Republic and England. Secular commissions were becoming more widespread, although the art of Spain and Italy (particularly Rome) was dominated by religious genres patronised by the church. Rome provides a logical starting point, given its artistic importance during the seventeenth century. See 4.1 Explore this example if you want to move outside Italy in the seventeenth century to investigate the context of the Dutch Republic.

In the early sixteenth century, Protestantism was gaining a considerable following in northern Europe following a successful campaign against the Catholic Church led by German priest and professor of theology Martin Luther (1483–1546). Luther is commonly agreed to have initiated the Protestant Reformation in 1517. The charismatic leader of this tidal religious change visited Rome in 1510 and was shocked by the corruption he witnessed in the Catholic Church, particularly in relation to the sale of indulgences. Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses (disputes with the church) on the church door at Wittenberg, Germany in 1517, an act that marked the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

A further blow to the status of the Catholic Church was the sack of Rome and the pillaging of its churches in 1527 by Charles V’s mercenaries, during which the then Pope, Clement VII, was forced to pay a ransom in order to escape. However, by the end of the sixteenth century, the city had been rebuilt to appear more resplendent than ever. Countless new churches, chapels and streets reasserted the authority of Catholicism and buried the memory of its past humiliation. Rome was transformed from a poor, ruined town to a vibrant city: the Catholic Counter-Reformation had arrived with the power of the Baroque style at its service.

On the theological front in the mid-sixteenth century, Pope Paul III (1468–1549) counteracted the threat from Protestantism by re-establishing the orthodox rules of Catholicism at the Council of Trent (a general church council established in the small Italian town of Trent). The Council of Trent convened over a 20-year period between 1545 and 1563. It issued instructions to educate the laity, enrolling the arts to strengthen the Roman Catholic faith. Crucially, it recommended that these instructions be communicated by artists as clearly as possible. According to art historian Rudolf Wittkower the Council of Trent laid down rules broadly under three headings:

- ‘Clarity, simplicity and intelligibility’: many stories relating to saints deal with martyrdom, brutality, horror and truth, in the sense that Christ must be shown afflicted, bleeding, spat upon, with His skin torn, wounded, deformed, pale and unsightly, if needed. And yet, decorum should be maintained (e.g. no nudity).

- ‘Realistic interpretation’: precise adherence to the Scriptures should be maintained.

- ‘Emotional stimulus to piety’: there was a new emphasis on martyrdoms to stimulate emotional responses from the faithful and new saints to celebrate: Ignatius Loyola, Charles Borromeo, Teresa of Ávila, Philip Neri and Francis Xavier were all canonised between 1610 and 1622.

The Council encouraged the establishment of new religious orders of monks and nuns and heralded a religious transformation that led to a more triumphant Catholicism. The Council of Trent was convened numerous times, but its most significant meetings were in 1545 to discuss Luther’s Theses and, in 1563, to recommend the employment of art as an integral part of the Counter-Reformatory process. The Council recommended that the power of the visual image be used to combat the austerity of the Protestant faith. It proposed that art should enable the observer to continuously remember the mysteries of our faith and Caravaggio (originally Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571–1610), the painter-cum-criminal, delivered upon the brief when he created some of the most memorable religious images ever painted.

Figure 4.1 | Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1602–1604, oil on canvas, 300 × 203 cm, Rome, Pinacoteca Vaticana.

Source: akg-images.

Painted for a side chapel in Santa Maria in Vallicella, The Entombment of Christ, 1602–1604, is one of Caravaggio’s less controversial works. Nevertheless, this sacred altarpiece risks breaching decorum, with Christ’s slightly over-exposed buttock and Joseph of Arimathea’s (sometimes identified as St. John) dirty fingers delving into Christ’s open wound. Six religious figures emerge from a tenebristic void, illuminated by an artfully angled candlelight; the splayed fingers of Mary of Cleopas (sometimes thought to be Mary Magdalene, who is adjacent), at the top right, compete for our attention with the weathered-looking Nicodemus, on the central vertical axis, who insists upon returning our gaze, seemingly including us in the scene. The tale of Christ’s body being lowered into his tomb is retold here with unprecedented realism for the time; but owing to the daring spatial composition, it almost seems as if he is also being lowered onto us, or the repentant laity of the time. Thus, it’s not only the sprouting plant in the foreground that signifies life; we seem to be there too, breathing the same air. As art historian Ann Sutherland Harris points out, Caravaggio’s painting seems to offer us as viewers the opportunity to ‘receive’ the body of Christ, just as the priest traditionally raises the host (the bread that symbolises the body of Christ) to bless it during the Mass. Harris also draws our attention to Christ’s left hand with its awkwardly contracted fingers frozen by rigor mortis, an accurate observation of death by an artist intent on presenting the laity with the ugly truth and on bringing out the full meaning of the embodiment of God as man (Harris, Seventeenth-Century Art and Architecture, p. 47).

While the Council of Trent busied itself with the sanctity of the Bible, Caravaggio imbued Scriptures with perhaps a little too much humanism. Fortunately for him, his unique ability to reach out to all men – even the sinners – followed what had been declared a Holy Year, 1600, in Rome. A Holy Year or Jubilee is mentioned in the Bible, which describes God’s mercy being granted on such an occasion. In what ways do you think Holy Year may have granted Caravaggio’s often indecorous images a degree of immunity?

Caravaggio was not the only artist to greet the Baroque era with a hy-perbolic sense of drama; the Italian painter, sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) would at least match Caravaggio’s ability to create an almost cinematic experience for the viewer, exemplified in his Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Ávila, 1645–1652. St. Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) was a Spanish nun who entered the Carmelite Order at the age of 21 and founded the order of the nuns of Teresa of Ávila. During her life she preached spirituality, modesty and poverty, and after her death she was made a saint. Her widely read autobiography describes her religious visions and gives an insight into the socio-religious context of seventeenth-century art.

In his hands I saw a great golden spear, and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he pulled it out, I felt that he took them with him and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. The pain was so severe that it made me mutter several moans. The sweetness caused by this intense pain is so extreme that one cannot possibly wish it to cease, nor is one’s soul then content with anything but God. This is not a physical, but a spiritual pain, though the body has some share in it – even a considerable share.

(Teresa of Ávila and Cohen, The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself, p. 210)

Bernini brought one of her spiritual encounters with God vividly to life, bringing heaven down to earth in a moment of transverberation. The seraphim’s drapery flutters with a heavenly lightness, while St. Teresa’s billows dramatically, emphasising the materiality of the human realm.

Contained in an aedicule crowned with a broken pediment and flanked by polychromatic marble, the pair are ‘illuminated’ by natural light that filters through a concealed yellow-tinted glass lantern above the scene, reinforced by golden ‘rays’ made of coloured stucco that provide arguably the most theatrical and illusionistic backdrop in sculptural history. With this piece, Bernini has created a bel composto, a beautiful whole comprising component parts: painting, sculpture and architecture. It was a stage design, a theatrical performance and a sensory delight that chimed with Counter-Reformation propaganda.

The intensity and bodily character of St. Teresa’s visions were in accord with Spanish Saint Ignatius Loyola’s book of Spiritual Exercises. Loyola (1491–1556) believed that the re-enactment of scenes of mystical experiences, such as that of St. Teresa, would inspire devotion in all those who beheld the spectacle. The renewed significance of saints, martyrdoms and the mysteries of their faith became the papacy’s most effective tool during the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

The Society of Jesus, known as Jesuits, was founded by Loyola in 1539. His own conversion experience inspired his book of Spiritual Exercises,1548. The society preached the upholding of the fundamental rules of the Catholic faith and aided the impetus of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. The Spiritual Exercises taught meditative prayer techniques and disseminated a strict obedience to the church. In the same way that a person’s physical well-being is aided by walking or running, so their spiritual well-being was considered to be aided by spiritual exercises. For just as strolling, walking and running are exercises for the body, so ‘spiritual exercises’ were a way of preparing and disposing one’s soul to rid oneself of all disordered attachments; once rid of them one might seek and find the divine will in regard to the disposition of one’s life for the good of the soul (Loyola and Munitiz, Saint Ignatius Loyola: Personal Writings, p. 283).

Figure 4.2 | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Ávila, 1645–1652, marble, height 350 cm, Rome, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria. Source: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Library / G. Nimatallah.

As well as the broader social and historical contexts within which a work of art was produced, specific events in the life of an artist or patron may also have an influence on artistic output. For example, seventeenth-century artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656), whose Baroque style was examined in Chapter 3, may be re-examined here under the theme of social and historical contexts in two ways: firstly, as a visual manifestation of rhetorical art in a country fighting to preserve the Catholic faith; and, secondly, as a possible response to the artist’s seduction and betrayal by a friend and fellow artist of her painter-father, Orazio Lomi Gentileschi. Gentileschi’s treatment can be seen to reveal the relatively harsh attitudes towards sexual relations outside wedlock during this period, as well as the unequal treatment of women in a patriarchal, or male-dominated, society.

Figure 4.3 | Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, c.1620, oil on canvas, 199 × 162 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Source: © 2015. Photo Scala, Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali.

Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, 1620, represents the biblical story of Judith, a Jewish widow, who, with her maid Abra, murdered the Assyrian general Holofernes. He had laid siege to the women’s town Bethuliah, and this image depicts the two women killing the brute with his own sword. An incident in the artist’s own life may account for the determination of the protagonists in this scene: the much older and more established painter, Agostino Tasso, seduced the young Artemisia in the guise of her teacher. A woman’s virginity was a significant ‘value’ in Renaissance society, and Artemisia’s father attempted to redeem her honour by accusing Tasso of rape. The trial, conducted during or just before this scene, subjected Gentileschi to humiliating physical examination and torture with thumbscrews.

Our knowledge of Gentileschi’s endurance may lead us to a particular interpretation of the scene: as though about to butcher a side of meat, the female slayers push up their sleeves to conduct the task with an unhesitating zeal for its completion. The artist’s literacy was both a Baroque trait and a characteristic response to the honest interpretation of the Scriptures in accordance with those rules laid down by the Council of Trent. Compare the following passage from the Book of Judith 13:4–9 with Gentileschi’s visual interpretation of the act:

- So all went forth and none was left in the bedchamber, neither little nor great. Then Judith, standing by his bed, said in her heart, O Lord God of all power, look at this present upon the works of mine hands for the exaltation of Jerusalem.

- For now is the time to help thine inheritance, and to execute thine enterprises to the destruction of the enemies which are risen against us.

- Then she came to the pillar of the bed, which was at Holofernes’ head, and took down his fauchion from thence,

- And approached to his bed, and took hold of the hair of his head, and said, Strengthen me, O Lord God of Israel, this day.

- And she smote twice upon his neck with all her might, and she took away his head from him.

- And tumbled his body down from the bed, and pulled down the canopy from the pillars; and anon after she went forth, and gave Holofernes’ head to her maid.

The works of Caravaggio, Bernini and Gentileschi are bound by a similar commitment to vivid and intensely bodily interpretations of biblical stories, and their uses of dramatic and rhetorically persuasive artistic devices draw us deep into the Counter-Reformation propaganda of their particular historical period.

During these years, Catholicism in Europe regained its might by strategic means: it established the Council of Trent to support papal power and Catholic dogma; captured the hearts and minds of the laity with new religious orders; celebrated the lives of the saints and used art and architecture to make the Catholic faith and the mystical visions of Catholic saints accessible and inspirational to the masses. The propaganda machine was designed to transform as many people as possible: heretics, Protestants, wavering Catholics and agnostics.

Seventeenth-century Italian architecture was just as dynamic and theatrical as painting and sculpture. Richly ornamented and grandiose in scale, Baroque buildings spoke to the laity using the same energising language – a kind of counter-reformatory syntax – comprising bouncy-looking volutes, raking cornices, light and shade, convexity and concavity – all interplaying with characteristic theatricality. See 4.2 Explore this example.

The art and architecture of mid-nineteenth-century France is just as richly infused with the social and historical circumstances of its time as was that of Italy in the seventeenth century. Paris, in particular, was undergoing tremendous social and technological changes.

Nineteenth-Century France: Transformation and Modernity

Emperor Napoleon III ruled France from 1852 to 1870, during which time he brought about an unprecedented renovation of Paris. The project was led by the Seine prefect Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who conceived the wide boulevards, public parks and city facilities to create the Paris we know today. The period of upheaval caused by the modernisation and transformation of the city would become known as ‘Haussmannisation’.

The housing Haussmann replaced had mostly been overcrowded and insanitary, carrying the constant threat of disease. Haussmann’s grand improvement project was welcomed by some of the area’s inhabitants, but the demolition of the old Paris also dismantled the social cohesion that had existed among its poverty-stricken inhabitants. Consequently, Haussmann has been remembered in the conflicting roles of both hero and destroyer. Works of art of the period provide evidence for both roles in equal measure.

Reportedly, Haussmann had endured a sickly childhood, much of which was blamed upon the polluted Parisian air. Correlations have been drawn between his zeal to eliminate the old Paris and rebuild the new with his personal interest in clean air and water. Whatever the motivation, the new sewer system he initiated in the 1850s was clearly a positive contribution to the health and safety of its citizens.

How ugly Paris seems after a year’s absence. How one chokes in these dark, narrow and dank corridors that we like to call the streets of Paris! One would think that one was in a subterranean city, that’s how heavy is the atmosphere, how profound is the darkness!

(Vicomte de Launay quoted in Rice, Parisian Views, p. 9)

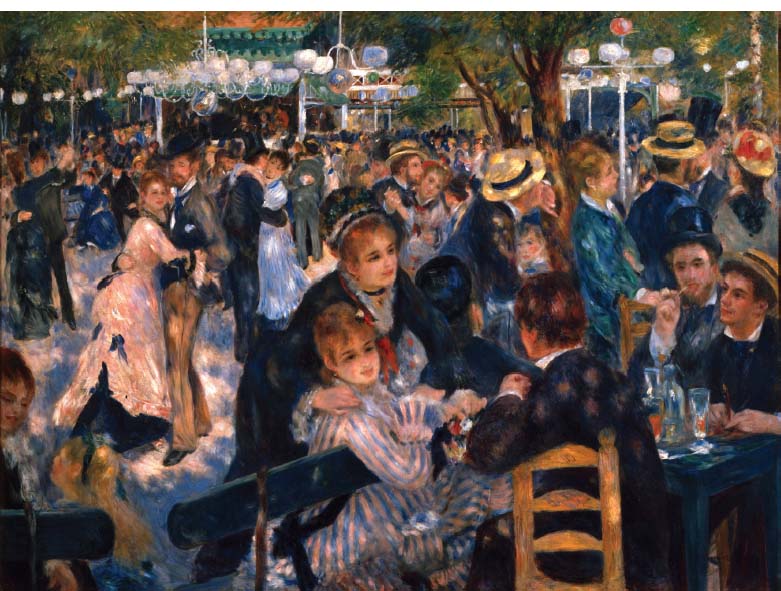

The polarised experiences of Parisians during this period may be demonstrated if we juxtapose two contemporaneous nineteenth-century scenes: Bal du Moulin de la Galette à Montmartre by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841– 1919) and L’ Absinthe by Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Renoir’s Bal du Mou-Nineteenth-Century France:Transformation and Modernity Social and Historical Contextslin de la Galette, 1876, shows a typically fun-filled late nineteenth-century scene in Montmartre. It captures the spirit of this highly sociable outdoor recreation space and well-known haunt of Parisian good-timers. However, beyond the brightly lit dabs of Renoir’s brush there lurks evidence of a darker side to Parisian life: a crowd of excluded onlookers, emitting a sense of loneliness. Sexual favours and the drinking of absinthe (a very strong green alcohol) may be the sub-text in Renoir’s painting, but the latter and all its societal ills are the explicit focus of Degas’ baldly named L’Absinthe. According to a contemporary observer, H.P. Hugh, The sickly odour of absinthe lies heavily in the air. The absinthe hour of the Boulevards begins vaguely at half-past five … but the deadly opal drink lasts longer than anything else (quoted in Adams, ‘The Drink that Fuelled a Nation’s Art’)

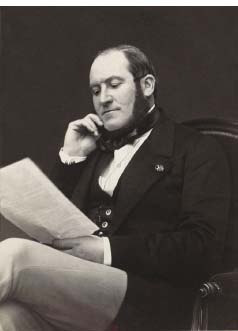

Figure 4.4 | Georges-Eugène Haussmann.

Source: © Paul John Fearn / Alamy.

Figure 4.5 | Charles Marville, Rue du Jardinet, from passage Hautefeuille, Paris, 1858–1878, black and white photograph.

Source: Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images.

Haussmann destroyed dirty, narrow streets like these and replaced them with clean, bright, wide ones suitable for strolling along.

We have sewn rags onto the purple robe of a queen; we have built within Paris two cities, quite different and quite hostile: the city of luxury, surrounded, besieged by the city of misery … you have put temptation and covetousness side by side.

(Louis Lazare quoted in Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, p. 29)

Figure 4.6 | Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette à Montmartre, 1876, oil on canvas, 131 × 175 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

Source: © 2015. A. Dagli Orti / Scala, Florence.

The reaction to paintings such as Degas’ was twofold: on the one hand, avant-garde artists, together with sympathetic critics such as the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), felt invigorated by the new subject matter; but on the other hand, the more conservative artistic and critical establishment needed some time to catch up with the social change to which it was increasingly bearing witness. Read the extract from The Westminster Gazette, 1893, for an insight into the painting’s reception (see 4.1 Critical debates: one response to L’Absinthe). Degas’ absinthe drinkers may be seen as victims of the destruction of their homes and former neighbourhoods as Haussmann’s workers built the new boulevards and apartments. Their looming sense of alienation is also to be found in works such as Manet’s Absinthe Drinker, 1858–1859 and his A Bar at the Folies Bergères, 1882.

Figure 4.7 | Edgar Degas, L’Absinthe, 1873, oil on canvas, 92 × 68 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

Source: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France /Bridgeman Images.

Some writers have claimed that Napoleon III encouraged the building of long, wide and straight boulevards to deter insurgents from building barricades – indeed, even the installation of street lights might be seen as aiding the ruler’s surveillance of his citizens. The streets of Paris had a history of revolution, which included the July Revolution (the so-called ‘Three Glorious Days’) of 1830, the June Rebellion of 1832 and the February Revolution of 1848. It may be that France’s new ruler felt that this history of revolution had to be stopped in the streets.

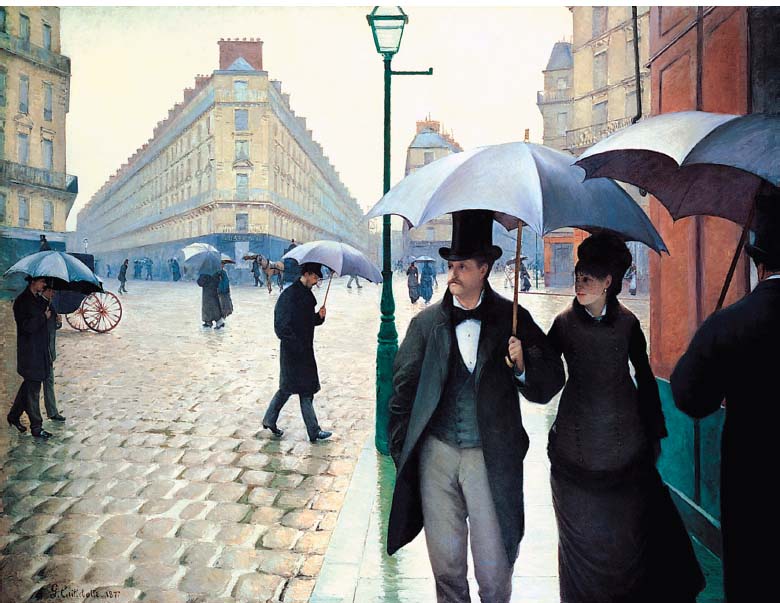

The painting Paris Street; Rainy Day, painted in 1877 by Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894), offers an almost photographic representation of Haussmann’s newly built Paris. Various wide boulevards radiate from a central intersection, providing a panoramic view of new streets on an epic scale. Perhaps Caillebotte’s is a truthful description of the historical nature of the scene, or perhaps it celebrates the monumental achievements of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann. The scene is populated by the haute bourgeoisie, and the approaching couple, far right, are certainly well-dressed members of its rank. Formally, it may depart from the Impressionist style but the painting certainly captures the transient feel of a modern, urban scene in a wealthy Parisian street. As the rain falls down, the main couple draw uncomfortably closer to us with each step.

Technological advances in photography (see 4.1 Let’s connect the themes: materials and techniques – early photography) had a significant impact on artists because the camera was able to quickly and accurately reproduce the natural world, placing greater pressure on artists to display creative ingenuity in order to match or surpass its achievements. Partly as a result of its invention, perhaps, the Impressionists of the latter half of the nineteenth century searched for new ways to capture their material world; a modern world characterised by the transient and the fleeting. An interest in the effects of light and a greater understanding of optics defined the Zeitgeist. Arguably, photography inspired the Impressionists both to aim to capture a moment in time and to ‘crop’ their compositions to create a ‘slice-of-life’ painting.

Figure 4.8 | Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas, 212 × 276 cm, the Art Institute of Chicago.

Source: © 2015. Photo Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Scala, Florence.

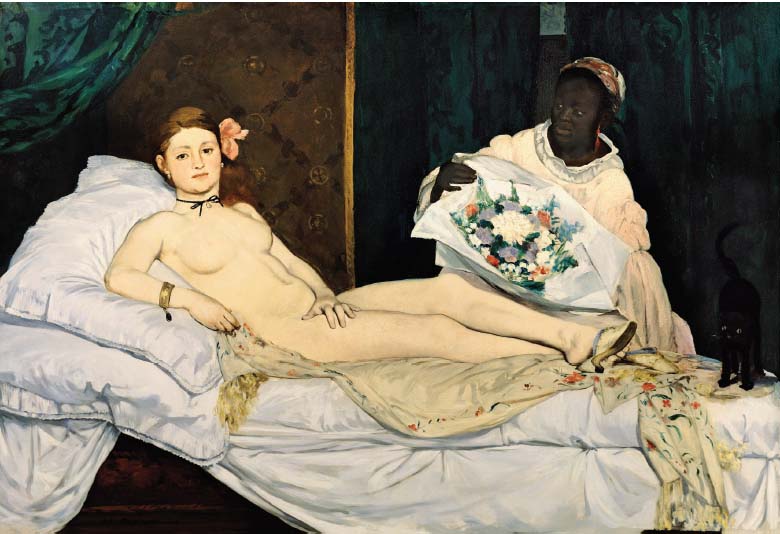

Figure 4.9 | Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130.5 × 190 cm, Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

Source: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images.

The train, the electric telegraph and photography were major inventions in the mid-nineteenth century and collectively they changed our perceptions of time itself. Photography managed to suspend a moment in time and the capture of the transitory moment became an important part of the Impressionists’ new aesthetic. The Impressionists responded to a new and modern world – modernity – as did fellow French artist, and friend to the group, Édouard Manet. In fact, Manet was among the first to consciously respond to the change. The French poet Baudelaire (1821–1867) suggested that every period had its own form of beauty and that the mid-nineteenth century contained an element of the eternal and an element of the transitory. The modern hero, according to Baudelaire, had shed his antique cloak and donned the ‘frock coat’ instead; the top-hatted dandy, voyeur, or flâneur, was, for Baudelaire, the ultimate observer of modernity. According to French writer Antonin Proust, Manet was one such a character – the archetypal painter of modern life, and an artist who immortalised his times and their spirit. Proust wrote:

I have already said what a flâneur Manet was. We strolled together one day, along what was later to be the Boulevard Malesherbes, through the midst of the demolitions, intersected by gaping holes where the ground had already been levelled. The Monceau district had not yet been planned … Farther on, house-beaters stood out white against a wall less white, which was collapsing under their blows, covering them in a cloud of dust. For a long time Manet remained absorbed in admiration of this scene … A woman came out of a low tavern holding up her dress and clutching a guitar; Manet went straight up to her and asked her to pose for him. She began to laugh. (Quoted in Frascina et al., Modernity and Modernism, p. 95)

Olympia, 1863, by Édouard Manet (1832–1883) was so ‘of the times’ that, as we have seen in Chapter 1, the Salon couldn’t cope with the furore she caused. Its initial reception devastated the artist – The insults rain down on me like hail, he complained to his supporter and friend, Baudelaire (Manet quoted in Krell, Manet, p. 67). Manet’s modern nude was far too recognisable as a contemporary courtesan to sit comfortably with the prudish sensibilities of upper-middle-class Parisians. As Clark states:

The baron’s demolitions had laid waste some famous streets of brothels near the Louvre and on the Ile de la Cité; the general rise in rents had obliged the owners of some brothels to move them out to the periphery, and many more to convert their establishments into hôtels garnis at the disposal of the individual streetwalker. The city had changed shape, and the usual places in which the prostitute sought her client – places where men danced, drank, took dinner, or were entertained – had multiplied and become more conspicuous. (Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, p. 106)

For Manet, however, she was one of the outcast characters of Baudelaire’s modernity. This reclining goddess was too ‘modern’ – she represented perhaps the first ‘shock of the new’. The artists of the times couldn’t wait to celebrate the new subjects of modernity, however: the prostitutes, the absinthe drinkers, the working women, the haute bourgeoisie, the dancers, the music halls, the cafés – all of these, the products of their social and historical contexts – were no longer hidden away but instead were paraded by these artists as symbols of modernity. In the words of Baudelaire, their first great literary ambassador: The pageant of fashionable life and the thousands of floating existences – criminals and kept women – which drift about in the underworld of a great city; the Gazette des Tribuaux and the Moniteur all prove to us that we have only to open our eyes to recognise our heroism. (Quoted in Edwards, Art and Its Histories: A Reader, pp. 195–196)

Look at Manet’s equally famous work, A Bar at the Folies Bergère, 1882, and think about how the top-hatted dandy reflected in the right-hand side of the picture may relate to Baron Haussmann’s newly created urban environment and artificially lit leisure spaces. The duality of Parisian society and its breathless transience is captured on film by director Baz Luhrmann in Moulin Rouge, 2001. The Moulin Rouge became a popular meeting place for Parisians to socialise and watch working girls in risqué performances. In the opening montage sequence of Luhrmann’s film we are reminded of the Impressionist style of painting and the modernity it sought to capture, in all of its breathless transience. One of the film’s central characters, the beautiful courtesan Satine, at one point says We’re creatures of the underworld – we can’t afford to love; a sentiment to be found also perhaps in the defiant eyes of Manet’s Olympia.

Napoleon III’s vision for the city’s new structure included the erection of a number of leisure spaces, including a new opera house, designed by architect Charles Garnier (1825–1898). The Opéra Garnier was built between 1862 and 1875, and the uniformity and grandeur of its façade are particularly striking.15 It is still one of the French capital’s most admired buildings. Situated at the top of the Avenue de l’Opéra, it is a visual manifestation of the process of ‘Haussmannisation’ and a monument to Napoleon III’s desire to place Paris on the world stage.

Figure 4.10 | Moulin Rouge, 2001, starring Nicole Kidman, directed by Baz Luhrmann. Dancing girls, courtesans, bright lights and dandies in frock coats capture a snapshot of Parisian modernity.

Source: 20th Century Fox /The Kobal Collection / Ellen von Unwerth.

The Opéra Garnier, a theatre for the opera and the ballet, is a statement of Napoleon’s power and authority. Its large-scale interior space, with impressive sweeping staircase, match its lavish façade, which is fairly eclectic, being heavily influenced by the Baroque style. Garlands, bas-reliefs, gargoyle masks and gilded sculptures symbolically reinforce the political rhetoric of the Second Empire.

Figure 4.11 | Avenue de l’Opéra, Paris, 1904.

Source: © Mary Evans Picture Library / Alamy.

Figure 4.12 | Opéra Garnier (Paris Opera), Paris, 1862–1875.

Source: © Rainbow / iStockphoto.

Paris was not the only important European city of the nineteenth century. London, too, had a claim to historical importance at this time, and its own distinctive art soon arose to match this context.

Mid-Nineteenth-Century England and Victorian Morality

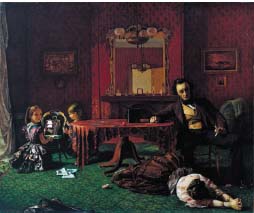

Figure 4.13 | Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present 1, 1858, oil paint on canvas, 63 × 76 cm, London, Tate Britain.

Source: ©Tate, London 2015.

Figure 4.14 | Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present 2,

1858, oil paint on canvas, 63 × 76 cm, London, Tate Britain.

Source: ©Tate, London 2015.

Figure 4.15 | Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present 3, 1858, oil paint on canvas, 63 × 76 cm, London, Tate Britain.

Source: ©Tate, London 2015.

Mid-nineteenth-century England had its own unique social and historical contexts to fuel artistic output. Although social and legal reform was afoot, the period was still plagued with ambivalence and hypocrisy when it came to morality, especially in relation to issues such as prostitution and adultery. We can see this drawn out in the period’s art, poetry and literature.

In the serial narrative painting Past and Present, 1858, by Augustus Leopold Egg (1816–1863), we learn about the terrible fate that befalls a woman who is an adulteress. We are reminded that we have choices in life, but are warned about making the wrong one. The first image in the series shows a woman collapsed, like her children’s collapsing house of cards, shown in Figure 4.13. Her husband holds a letter which presumably presents evidence of her adulterous affair. The second and third images provide us with two simultaneous frames: the second image in Figure 4.14 shows the woman’s children from her legitimate marriage praying for their mother’s return, while the third (Figure 4.15), under the same moon, shows the mother alone near the banks of the Thames; she is utterly destitute with only her illegitimate child for company. This work was intended to be read like a book and its message mirrored the prevailing attitudes of the era.

Victorian legislation demonstrated institutionalised inequality between men and women, and the following two parliamentary acts may be read in conjunction with our interpretation of both the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience and Egg’s Past and Present. The Matrimonial Causes Act (1857) reinforced gender inequality. Under this Act adultery was not sufficient grounds for a woman to divorce her husband, but it was for a man to divorce his wife. The Married Women’s Property Act (1882) allowed a married woman to retain ownership of her own property. Before this Act, even property gifted to her by a parent would have become the property of her husband.

Victorian feminists, such as Barbara Leigh Smith, foremost founder of the Women’s Rights Movement, challenged the Victorian idea of women’s inherent weakness and subsequent domination. So too, perhaps, did Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) in his famous work The Awakening Conscience, 1853.

Hunt breaks with convention when he depicts both the perpetrator/seducer and the victim/seduced in his painting. We are given insight into the process of this woman’s ‘fall’ from grace and respectability and, in so doing, Hunt challenges the idea that we are all responsible for our choices and moral improvement. In comparison with the paintings of his contemporary Augustus Egg, which charts the dire consequences of a woman’s adultery, Hunt gives us a sense of the social injustice prevalent in Victorian England. Each work may therefore be read as alternative responses to ‘the great social evil’ – women’s sexual immorality – which seemed to threaten the period’s cherished morality. While we are led to believe that Egg’s subject must inevitably die for her ‘deviance’, Hunt’s subject is allowed to bathe for a moment in the light of her possible redemption, and we feel genuinely uplifted by the prospect.

Figure 4.16 | William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, oil on canvas, 74.9 × 55.8 cm, London, Tate Gallery.

Source: © 2015. DeAgostini Picture Library / Scala, Florence.

Being a kept woman could save a working-class girl from the stresses of the factory, but only for as long as she was still wanted. The seducer has already cast off one glove without a care, and we might read this as an indication of the woman’s inevitable fate. The seducer’s right hand extends to catch her hands – which are clasped together in a moment of untutored prayer – and the obvious lack of a ring on her finger reminds us that he’s not offering his mistress betrothal – ever. Rising from her keeper’s lap, she sees the light, towards which she seems to move as if in a spiritual trance, approaching ever nearer to the open window, a metaphor for her potential freedom and salvation. Indeed, the outdoors is every bit as significant as Hunt’s meticulously painted interior: he’s reflected it in the mirror on the back wall. However, we also see a cat toy with its prey, bottom left, an allusion to the way in which men might toy with their mistresses, in this context. Will the bird get away? Will she? Hunt makes us long for her escape.

There is some evidence that the times were beginning to change for the better in terms of social attitudes towards women. The towering figure of Victorian criticism John Ruskin wrote in a letter to The Times in 1854 about Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience: There will not be found one powerful as this to meet full in the front the moral evil of the age in which it is painted; to waken into mercy the cruel thoughtlessness of youth, and subdue the severities of judgement into the sanctity of compassion (quoted in Golby, Culture and Society in Britain 1850–1900, p. 104).

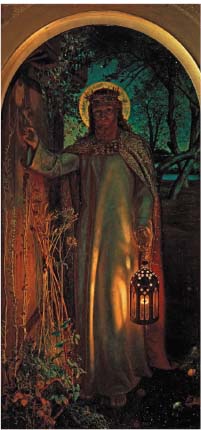

Figure 4.17 | William Holman Hunt, The Light of the World, 1853, Oxford, Keble College.

Source: akg-images.

Figure 4.18 | William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, oil on canvas, 74.9 × 55.8 cm, London, Tate Gallery. Source: © 2015. DeAgostini Picture Library / Scala, Florence.

Ruskin urges the reader not to judge this ‘poor’ young woman too hastily, despite her kept status characterising the ‘moral evil’ of the age.

That Hunt intended to inspire kindness and forgiveness towards those less fortunate is further supported by another of Hunt’s paintings, The Light of the World, 1853. Viewing these paintings together, we are reassured that our protagonist has heard Christ’s knock on the door and that in The Awakening Conscience we are shown the moment she finds her path to salvation.

The idea that society should accept a certain moral responsibility towards the underprivileged, the downtrodden and the destitute is one which grows slowly in strength and commitment during this period, although arguably Hunt’s painting retains a notion of individual conscience as the most important agent of change. The strictly hierarchical class system prevalent during the Victorian era was another form of social entrapment. The fate of the working-class prostitute was usually a sad one, but that of the middle-class adulteress was also likely to be bad; society at the time simply could not find any justification for it. See 4.4 Explore this example for a contemporary focus on an altogether different kind of moral evil.

The tragic plight of those less fortunate seems to be a timeless occurrence. In the following century, the United States suffered a crisis that would have a lasting effect, not just on its lower classes, but on the majority of its citizens.

Mid-Twentieth-Century United States and the Depression Era

The Great Depression of the 1930s was a defining period in the history of the United States, as it was in many countries whose economy and financial system were dependent on that of the United States. During the 1920s the United States had appeared to be booming, with factories turning out consumer products and share prices rising. But all that changed in 1929. Quite why it did so is a matter of debate among economists, but it seems that an over-supply of goods led to falling prices, people lost confidence in the financial system and the stock market tumbled, finally crashing on 29 October 1929. Mass panic ensued as people rushed to withdraw their savings from the banks. Some banks collapsed, leaving many major investors and ordinary people bankrupt. People who had thought their savings were secure were left with no money and no job, and many became reliant on soup kitchens and handouts. Similar hardship was felt across the Western world, but artists in the United States in particular produced some of the most iconic images of these economically difficult times.

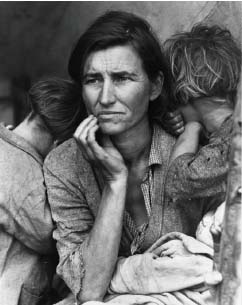

Figure 4.19 | Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, 1935, Nipomo Valley, 28.2 × 21.6 cm.

Source: Library of Congress.

Photographer Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) was commissioned by the US Government’s Farm Security Administration to record the devastation being wreaked on the agricultural economy of the country’s Mid-West. But her photographs turned out to be something more than simply ‘records’; she captured the pain and despair of the farm labourers in photographs that have strong aesthetic qualities. The weight of the world is clear upon a woman’s face in Migrant Mother, one of Lange’s many images of migrant labourers in California. This iconic image was published in a San Francisco newspaper and brought the plight of the rural community into the consciousness of every American. It even led to practical help from the government, who were alerted to the plight of the migrant workers in the camp Lange had photographed and sent food aid.

The stock market crash of 1929 was felt particularly badly in the Mid-West, where falling prices for agricultural products were compounded by the impact of over-farming and the use of grazing fields for crops, which left the soil infertile. This was exacerbated by drought, and the ensuing dust storms led to the term ‘Dust Bowl’ being used. Whole families left their farms and took to the roads in search of work, experiencing intense suffering due to the lack of food and clean water along the way.

Lange’s photographic portrayal of the human condition embodies a depression that resonates in the oeuvre of the artist Edward Hopper (1882–1967). Hopper provides us with a sense of the impact of the Depression on city dwellers. With images rendered every bit as still as the photographer’s, Hopper conveys a sense of people’s self-reliance amid a hopelessness with a pigment-loaded brush.

Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942, which was discussed as a ‘genre’ painting in Chapter 1, is also a powerful illustration of the social and historical contexts from which it grew – life in the United States during the Depression. The usual frivolity associated with a leisure space is absent, and the dark palette is perhaps a metaphor for the hopelessness of America’s unemployed. Light is possibly the most significant formal device in Hopper’s oeuvre, and in Nighthawks light structures the composition and creates mood. We get the impression that the light from this all-American diner shines alone in an otherwise vacant street and does little to illuminate its characters. In common with the 1940s film noir that influenced Hopper’s visual style, the scene is arranged like a set; the mise-en-scène provides the signifiers: the only sense of movement is the presumably recent departure of the customer who left the unaccompanied tumbler on the bar. Their departure provides a sense of relief that somebody has shifted in this space, but it also allows us to scrutinise the couple on the other side of the counter: both are deeply reflective. Perhaps the dolled-up woman in the red dress is checking the bill, or perhaps we are in danger of reading too much of the economic context into the painting. What do you think would happen in this scene if this frozen image came to life?

The context of Nighthawks is one in which the government and the banks were perceived to have failed their citizens, and Hopper’s paintings seem to be implicitly loaded with the heroism of individual self-reliance in such harsh times. In the same way that Manet and Degas observed and commented on the social upheavals of their time, Hopper observes the scene with the detached gaze of a modern flâneur. He uses windows in his scenes to offer the viewer access to the human condition – a technique probably borrowed from cinematography. We are drawn closer and closer to the scene, but always kept at a distance, behind the viewing pane.

Figure 4.20 | Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas, 84.1 ×152.4 cm, Friends of American Art Collection, 1942.51, the Art Institute of Chicago.

Source: Photography ©The Art Institute of Chicago.

Twentieth-Century United States: The Boom Years

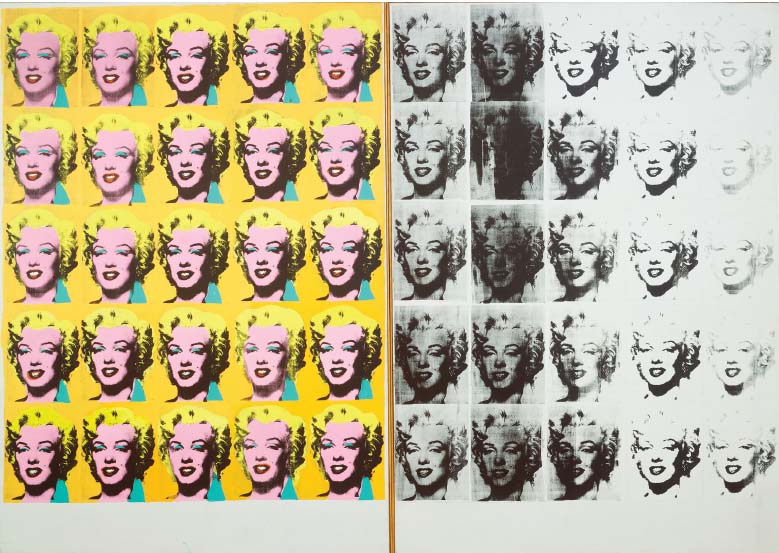

Figure 4.21 | Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962, acrylic paint on canvas, each panel 2054 × 1448 × 20 mm, 1962, London, Tate.

Source: ©Tate, London 2015 / © 2015The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

What is the effect of the technique of repetition on our interpretation of Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych?

The entry of the United States into the Second World War in 1941 brought the Great Depression to an end. During the immediate post-war period, the country experienced an economic boom, most clearly evident in domestic consumerism. By the time of John F. Kennedy’s presidency (1961–1963), the work of some American artists reflected this and the term Pop Art was used to describe it.

There is some debate about whether Pop Art images were a celebration of American life, a neutral commentary upon its consumerism or a satirical criticism of the commodification of everything. Most Pop Art is not explicitly critical of American society, but its representations of banal subjects have led to it being viewed as critiquing the culture that produced it. When Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein borrowed motifs from advertising, comics and magazine images – dispassionate, popular culture mediums – they exaggerated consumer identity and heightened our awareness of its superficiality.

Commercially trained Pop artist Andy Warhol (1928–1987) subverted elitism in the art world with the language of mass culture and, according to the German cultural historian Andreas Huyssen, conflated the ‘great divide’ between high art and mass culture (Huyssen, Introduction: After the Great Divide, Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism, pp. vii–x). Warhol was also acutely aware of the significance of celebrity and the idea of tragedy as spectacle in modern times.

Figure 4.22 | Marilyn Monroe, publicity photo for film Niagara, 1953.

Source: 20th Century Fox / Photofest.

In Marilyn Diptych, 1962, Warhol’s 50 similar (although not identical) images of movie icon Marilyn Monroe, produced shortly after the actress’ tragic and untimely death, utilise the silkscreen technique (see Chapter 2) to allow for the innumerable repetitions of one image and the mass production of an iconic celebrity. Warhol has summed up the existence of Norma Jean Baker (Marilyn Monroe’s real name) in the mask-like face of her pseudonym – her consumer identity, and all that she was reduced to.

Marilyn was known through films like Niagara (1953), from which this particular image was taken, but more widely through images of her screen persona reproduced countless times. Marilyn’s likeness is not Warhol’s creation, but one schematically recognisable as belonging to the media because it’s appropriated, reproduced and re-sold. If we want her, we can buy her in the form of cheap posters.

Reduced to units, stacked impersonally on top of one another, Marilyn has become arguably no different to the artist’s other famous repetitive commodities: soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles. Warhol fostered a mechanical style well suited to the mechanisation of American society and perhaps symptomatic of the repetitive labour processes of Fordism. This commodity philosophy seemed to be embodied in the impersonal touches of Warhol’s assistants, who worked in the studio that he rather aptly named The Factory. It was at The Factory where Warhol developed his screen printing technique and met with his celebrity friends, such as Lou Reed, Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger. Warhol’s Pop Art, with its unsigned, assembly-style ‘signs’ of the era, was certainly of the times – and those times were marked by consumerism, commodification and celebrity.

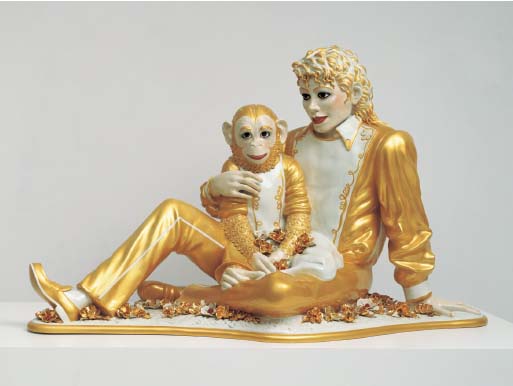

In the 1960s Warhol was good at finding images that fed society’s consumer fascination with the ‘human interest’ story, but a more recent sculpture by contemporary American artist Jeff Koons (born 1955), Michael Jackson and Bubbles, reminds us that our fascination with celebrity and tragedy persists.

This sculpture almost doesn’t need an identifying inscription, since Michael Jackson, the celebrity singing icon, is recognised the world over as a pop music legend. In 1988, when Koons produced this work, the singer was still enjoying universal success; however, since his unexpected death, he has become a tragic figure in a way that makes him comparable perhaps with Marilyn Monroe. Jackson and Bubbles, the performing duo, may be anatomically correct but they also seem excessively fake and doll-like. Their matching gold outfits, oversized black pupils and lips, painted in the same shade of red, render them stylised and cheaply ‘touristy’.

Figure 4.23 | Jeff Koons, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain, 106.7 × 179.1 × 82.6 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Source: © Jeff Koons.

The medium of porcelain is delicate and fragile, which may be interpreted as alluding to the fragile and temporary adulation enjoyed by celebrities like Michael Jackson. This richly embellished duo appears to have their venerated status mocked by the artist. Jackson envelops his surrogate baby in a way we might think we recognise from Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child (and indeed, the chimpanzee, with its fixed and knowing stare, seems to know more than his keeper, just as the Christ Child seems to have an adult presentiment of his fate). This can hardly be described as a portrait of Michael Jackson: it’s a portrayal of his marketable and consumer-loved persona– celebrity as the ultimate commodity. Unsettling in its superficiality, it may be read as a scathing attack on consumerism.

Jeff Koons is a mega-artist, rivalled only by Damien Hirst in commercial success and fame. He is also underrated as a fantastic chronicler of the modern world.

(Jones, ‘Jeff Koons: Not Just the King of Kitsch’)

Fittingly, Jeff Koons was a commodities broker before he became an artist. Moreover, he did not craft this sculpture himself but rather had it made for him by professional craftsmen, something which makes his ref-erencing of the mass-produced object of popular culture all the more ironic. Such mass-produced objects are the epitome of kitsch, which the American art critic Clement Greenberg (associated with Modernism)16 identified as cheaply entertaining and therefore threatening to the arts.17 In referencing this kitsch, Koons is arguably drawing our attention to the superficiality and banality of American culture.

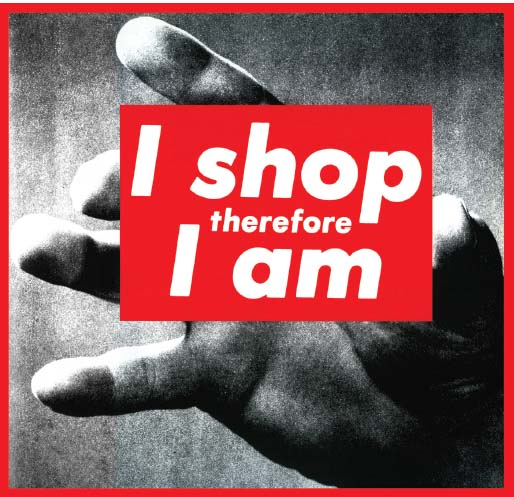

Cultural identity in terms of consumption occupied a range of artists in the latter half of the twentieth century. I Shop Therefore I Am, 1987, by American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger (born 1945) plays satirically on seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes’ famous axiom ‘I think therefore I am’ (Cogito ergo sum).

Figure 4.24 | Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am), 1987, photographic silkscreen/vinyl,282 × 287 cm, New York, Mary Boone Gallery, MBG#4057.

Source: Copyright: Barbara Kruger. Courtesy: Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Kruger’s statement draws attention to the fact that we used to think in order to know that we existed, but now we shop instead – the implication being that the latter is a meaningless substitute. Kruger’s bold type, assimilated from the media itself, strikes a familiar and authoritative tone. Her oeuvre features the juxtaposition of imagery and text, a common device of social critique.

The work of Warhol, Koons and Kruger poses the question: is consumerism the defining feature of our times? In his book The Ecstasy of Media Communication, French philosopher and cultural critic Jean Baudrillard argues that the media plays an ‘essential’ role in defining Western culture. He suggests that the traditional distinctions between ‘reality’ and ‘imitation’ no longer exist because the media produces images that are neither one nor the other, but are rather a mixture of both, creating what he calls a ‘hyperreality’. For example, Michael Jackson was ‘real’ but our knowledge of him through his portrayal in the media is ‘hyperreal’ – a simulation which is characteristic of our times.

The collapse of previously defined categories – a distinctly postmodern feature – casts an interesting light on the issue of social class. Strictly hierarchical in Victorian England, there is some evidence that class distinctions have fragmented in postmodern times.

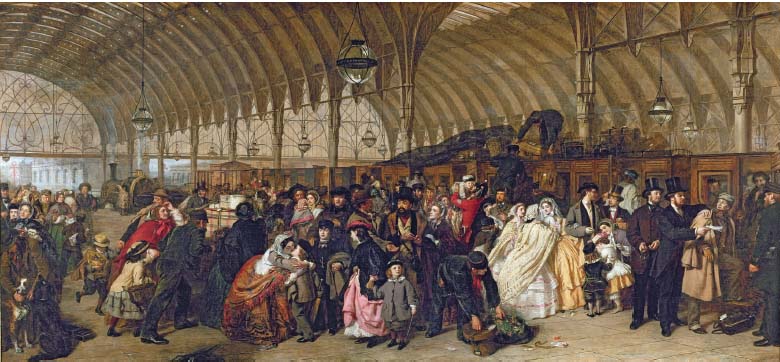

Class Fragmentation and the Urban Documentary

Victorian morality paintings, such as those featured previously by Augustus Leopold Egg and William Holman Hunt, pivoted around the issue of classbased norms. Social class features once again, at least as a sub-text, in The Railway Station, 1860–1862, by William Powell Frith (1819–1909). Frith’s painting of a busy platform at Paddington Station provides a microcosm of the hierarchy in Victorian society and an insightful commentary on the period’s technological advances. The changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, which had started in the UK in the mid-eighteenth century, were felt in every facet of the epoch, and the railway in particular became an emblematic sign of modernity.

What appears to be a rather chaotic scene on the station platform of Paddington is, upon closer inspection, a highly structured documentary of Victorian life: the crowds are organised compositionally in accordance with their social class, as art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon observes: The crowd has been organised as if in alignment with the train’s compartments, third class, second class and first class, so that to read the painting from left to right is to ascend smoothly from the lowest level of society to the highest (Graham-Dixon, A History of British Art, p. 160).

The image is imbued with the middle-class values that have come, perhaps stereotypically, to define the Victorian era: self-improvement, respectability and social position (or at least the outward appearance of such), and Frith’s restrained brushwork and recording of minutiae echo the political conservatism of the era and meticulously observed Victorian mores. Ironically, in an age when meritocracy was more of a myth than a reality, many individuals in Victorian England aspired to climb the social ladder. The preoccupation with an individual’s social standing was a common theme in literature, as well as painting; Thomas Hardy’s novel Jude the Obscure, 1895, is just one illustration of the rigid social scale that prevailed. Frith’s travellers are all dressed in clothing that reveals their class; every bonnet, top hat and crinoline tells a social story.

Figure 4.25 | William Powell Frith, The Railway Station, 1860–1862, oil on canvas, 117 × 256 cm, Royal Holloway, University of London/

Source: © Royal Holloway, University of London / Bridgeman Images.

Along with a changing social landscape, this was the time of technological progress and the train and its station illustrate this. Indeed, the railway seemed to have an almost religious significance for Britain’s most famous painter of the period, J.M.W. Turner; his Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, c.1844, captures the new technology’s essence in an ephemeral, light-saturated landscape.

The railway had a huge social and economic impact on mid-nineteenth-century Britain. By the 1860s the country was criss-crossed with a network of rail tracks, and many towns and villages had a local station. Trains enabled people to move out of their rural farming communities to seek employment in the cities, and they provided a cheap and fast method for transporting both industrial and agricultural products.

Quick and relatively affordable travel allowed day trips to the coast, with even poorer people able to afford this by travelling in open-topped carriages. Not everybody thought that this was a positive prospect. The Duke of Wellington – famous for his victory at the Battle of Waterloo, and subsequently a Tory prime minster – was afraid that trains would encourage poor and socially undesirable people to come to London.

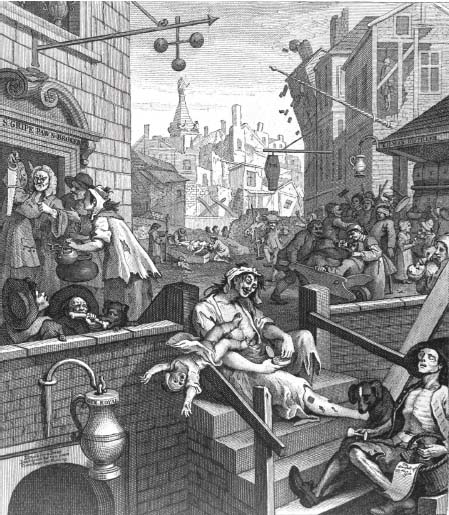

The impoverished classes were often represented as ‘other’ in Victorian England, their social failures used as moral warnings to the masses or their lives documented like grotesque spectacles of the era. Nevertheless, in ear-lier times, eighteenth-century satirist William Hogarth (1697–1764) sympathetically depicted the plight of the poor in images such as Gin Lane, 1751. Gin drinking was used as a means of escape from the harsh lives many of the poor in London and other cities experienced. Hogarth’s subjects were usually low-life and often syphilitic, but always bore resemblances to the characters of contemporary urban living, in common with so many artists who documented the times in which they lived.

Figure 4.26 | William Hogarth,Gin Lane, 1751, copper engraving and etching, 35.8 × 30.2 cm.

Source: akg-images.

Stereotypical depravity and drunkenness both shocked and gratified the rigidly hierarchical Victorians, but when contemporary artist Richard Billingham (born 1970) turned a camera lens on his own parents it was the fact that he, the class-conscious product of his subjects, was now a part of the establishment that prompted the question: have traditional class distinctions really collapsed in the twenty-first century? The idea of the death of social class resonated with 1980s individulism and Thatcherite values of free enterprise and social mobility.

Billingham exposes the grim reality of his family’s social conditions with almost unthinkable candour. Candour is a commodity, or so it seems, in recent times and, unsurprisingly, Billingham’s photographic confessions caught the attention of that most famous backer of the class-conscious, maverick and patron of the arts Charles Saatchi. Billingham’s commercial success arguably demonstrates meritocracy in operation and a distinct vogue, even celebrity prestige, in having climbed out of the Hogarthian gutter. In an extract from ‘We Are Family’ in Genius of Photography (Wall to Wall), Billingham states:

Figure 4.27 | Richard Billingham, Untitled, 1994, colour photograph mounted on aluminum,75 × 50 cm, Edition of 10 + 1AP.

Source: Copyright the artist, courtesy Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London.

I was living in this tower block; there was just me and him. He was an alcoholic, he would lie in bed, drink, get to sleep, wake up, get to sleep, didn’t know if it was day or night. But it was difficult to get him to stay still for more than say 20 minutes at a time so I thought that if I could take photographs of him that would act as a source material for these paintings and then I could make more detailed paintings later on. So that’s how I first started taking photographs. (Billingham, ‘We Are Family’)

Of course, contemporary artists such as Tracey Emin and Richard Billingham have been famously proud of their ‘in-your-face’ working-classness: their work is gritty, raw, confessional and immediately accessible to the masses. Both artists’ works have met with critical acclaim, perhaps because it suits our lay-everything-bare times. Since the 1990s the media has been saturated by voyeuristic glimpses of abject and dysfunctional families. Private lives unfold in TV programmes such as Celebrity Big Brother and My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding. Yet, however unnerving Billingham’s ‘fly-on-the-wall’ portraits are for the viewer, their authenticity makes them deeply poignant and brimming with social class narrative; even if Billingham’s example supports the idea that it is possible to move beyond a working-class background. There is certainly an irony in the fact that many of these ‘working-class’ artists enjoy levels of wealth that match or exceed that of their patrons.

The social and historical contexts of architecture have only been touched upon in this chapter because key buildings examined in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, are considered there in terms of their wider social and historical contexts. Considering that no work of art or architecture appears in a social and historical vacuum, and that every object is born of its times, the choices under this theme are as limitless as the works themselves.